Abstract

The biological parameters that determine the distribution of virus-specific CD8+ T cells during influenza infection are not all directly measurable by experimental techniques, but can be inferred through mathematical modeling. Mechanistic and semi-mechanistic ordinary differential equations were developed to describe the expansion, trafficking, and disappearance of activated virus-specific CD8+ T cells in lymph nodes, spleens, and lungs of mice during primary influenza A infection. An intensive sampling of virus-specific CD8+ T cells from these three compartments was used to inform the models. Rigorous statistical fitting of the models to the experimental data allowed estimation of important biological parameters. Although the draining lymph node is the first tissue in which antigen-specific CD8+ T cells are detected, it was found that the spleen contributes the greatest number of effector CD8+ T cells to the lung, with rates of expansion and migration that exceeded the draining lymph node. In addition, models that were based on the number and kinetics of professional antigen-presenting cells fit the data better than those based on viral load, suggesting that the immune response is limited by antigen-presentation rather than the amount of virus. Modeling also suggests that loss of effector T cells from the lung is significant and time-dependant, increasing towards the end of the acute response. Together these efforts provide a better understanding of the primary CD8+ T cell response to influenza infection, changing the view that the spleen plays a minor role in the primary immune response.

Keywords: Mathematical Model, Influenza, Virus, Immune, Lung, T cell, CD8+, Migration

INTRODUCTION

Current strategies for preventing or decreasing the severity of influenza infection focus on increasing virus-neutralizing antibody titers through vaccination, as experience indicates that this is the best way to prevent morbidity and mortality. It is generally accepted that T cells provide a substantial degree of protection from disease, and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells control the infection by eliminating infected cells when neutralizing antibodies are absent (1–3). Because influenza viruses are unique in their ability to undergo antigenic shift, resulting in a wholesale evasion of neutralizing antibodies, T cells that cross-react with conserved antigenic regions in the viruses are perhaps the most important immune component against emerging novel strains of the virus. Understanding the factors that regulate the T cell response is key to the development of new immunization strategies designed to promote cross-reactive immunity.

With the exception of certain highly pathogenic strains of influenza (4–6), the virus infection is usually restricted to the airways and lung tissues. This phenomenon is believed to be due to the limited expression of host enzymes required to cleave the viral hemagglutinin protein into its active conformation (7, 8). Because of this, it takes time for antigen (and antigen-presenting cells)to reach the draining lymph node (9, 10), and also for virus-specific effector CD8+ T cells to migrate through the blood stream back to the site of infection. The dynamic nature of this process makes it very difficult to study directly. Conventional approaches rely on tissue sampling at defined time points to assemble a set of “snapshots” that can be linked together to understand the system as a whole. Unfortunately, this understanding still depends on a number of assumptions. For example, a given tissue sampling tells us where the cells are at that point in time, but does not reveal where they came from. In addition, the rates of cell proliferation and trafficking into and out of a given tissue can, at best, be inferred. In the end, the number of cells at any single tissue site will depend on the combined, simultaneous processes of proliferation, trafficking, retention, and cell loss due to death, phagocytosis, or sloughing.

Mathematical modeling and computational approaches to the problem offer one of the best means to estimate the key biological parameters that cannot be directly and unambiguously measured. Mathematical models have long been used to investigate viral dynamics and immune responses to viral infections, including influenza A virus (IAV)(11–18). In particular, we recently developed complex differential equation models to quantify key kinetic parameters and predict early and adaptive immune responses against IAV infection (19, 20). However, limited by available experimental information, our previous studies mainly focused on the lung. Better understanding of immune cell kinetics among multiple compartments is thus a natural and necessary next step. To this goal, in this manuscript we propose new mathematical models of multi-compartment cell trafficking and fit them to experimental data from mice infected with the H3N2 influenza A/X31 strain. Based on model fitting results, we compare and verify several mechanistic hypotheses that cannot be directly inferred without mathematical models.

Materials and Methods

Murine Kinetic Experiments

Female C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Labs, Maine)from 6 to 13 weeks of age (n=78)were anesthetized with 2,2,2-tribromo-ethanol and intranasally inoculated with 0.03 ml of 1×105 EID50 H3N2 A/Hong Kong/X31 influenza A virus. Tissues for determination of CD8+ T cell counts were collected at days 0, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 28 post infection. At each time point, data were collected from 6 mice for most time points and 12 mice for day 12 for flow cytometry. Data from days 5 to 14 were used in modeling fitting to understand the cell trafficking during the adaptive phase. All experiments involving animals have been reviewed and approved by the University Committee for Animal Resources (IACUC).

Tissue Collection

On the day of organ harvest, mice were euthanized using a lethal dose of 2,2,2-tribromoethanol. Whole lung, mediastinal lymph nodes, and spleen tissues were isolated from individual mice. Single cell suspensions were prepared by Dounce homogenization or mechanical disruption with a fine mesh and suspended in MEM with 5% fetal bovine serum. Red blood cells were lysed using buffered ammonium chloride solution (Gey’s solution), and cells were resuspended in cMEM for analysis. Total lymphocyte numbers were obtained by manual counting using a hemacytometer, and confirmed in many samples by flow cytometry measurements.

Determination of Virus-specific CD8+ T Cell Immune Responses

Cell phenotypes were determined by flow cytometry after surface and intracellular staining. To determine the number of virus-specific CD8+ T cells, spleen cells from naïve B6.SJL (CD45.1+) mice were used as antigen presenting cells and infected with influenza (MOI=1)in 1 ml serum-free media for 60 min. Infected cells were then washed and resuspended in cMEM. 1×106 antigen presenting cells were added to 1×106 responders for a total volume of 100 μl. Golgi Plug (BD)was then diluted to 1 μl/ml in cMEM and 100 μl added to each well. Cells were incubated for 5~6 hr at 37°C. Samples were then surface stained for CD3, CD4, and CD8 and then washed and resuspended in Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD)100 μl/well for 15min. After one Perm/Wash (BD), anti-IFN-γ, anti-TNF-α, and anti-IL2 antibodies were added in Perm/Wash, and cells incubated for 30 min on ice in the dark. Samples were resuspended in PBS/BSA for FACS. Samples were analyzed on a BD LSRII cytometer and results were processed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.). The number of antigen-specific CD8+ cells per lung was calculated as follows:

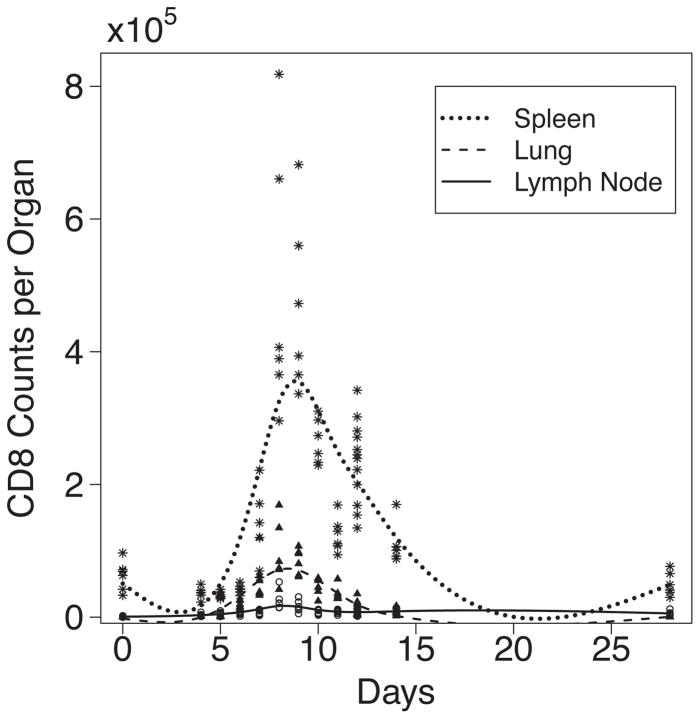

For this analysis, the total number of CD3+ CD8+ cells expressing one or more of the three cytokines TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-2 (TNF−IFN+IL2+, TNF−IFN+IL2−, TNF+IFN−IL2+, TNF+IFN−IL2−, TNF−IFN−IL2+, TNF+IFN+IL2+, and TNF+IFN+IL2−)was used as the number of virus-specific cells. See Fig. 1 for the observed CD8+ T cell counts in lymph node, spleen and lung.

Figure 1.

Experimental observations and smoothed curves for effector CD8+ T cells identified by intracellular cytokine staining for IL2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α in spleen, lung and lymph node post IAV infection. Experimental data indicated by ✶ spleen, ▲ lung, μMLN. Smoothed curves indicated by solid line for MLN, dotted line for spleen, and dashed line for lung.

Detection of Ag presentation by LN DC

Antigen presenting cells (APCs)were isolated essentially as described (10, 21). C57BL/6 mice for influenza experiments were obtained from The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research. Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. Experiments with mice began when they were between 6 and 10 wk of age. Mice were anesthetized with methoxyfluorane and then intranasally infected with a nonlethal challenge of H3N2 A/Hong Kong/X31 influenza A virus diluted in 25 μl of sterile PBS. The regional (mediastinal)draining LN were digested for 20 min at room temperature with collagenase/DNase and then treated for 5 min with EDTA to disrupt T cell DC complexes. Previously, it has been shown that depletion of cells expressing CD11c removed Ag-specific stimulatory capacity indicating that Ag presentation was limited to CD11c+ DC (9, 22). The LacZ-inducible hybridomas specific for Db nucleoprotein (NP)366–374 (BWZ-IFA.NP4)(9), Db acid polymerase (PA)224–233 (BWZ-IFA.PA1)were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FCS, 50 μM 2-ME, 2mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (hybridoma medium). These clones were used to analyze Ag presentation by LN cells, as previously described (23).

Mathematical Models and Assumptions

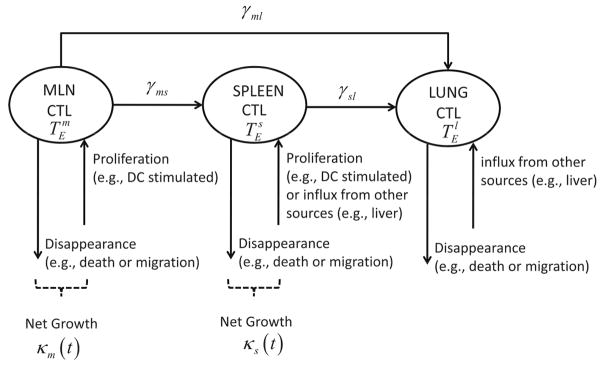

First, we consider a mechanistic model involving lymph node, spleen and lung to describe CD8+ T cell response to primary influenza A virus infection. For the mediastinal lymph node (MLN), we assume that there exist proliferation, migration to spleen, migration to lung, migration to other compartments, and apoptosis (death)or loss due to other mechanisms, and all these dynamic rates are proportional to the number of activated, effector CD8+ T cells, , in the MLN. Furthermore, we assume that the influx of CD8+ T cells from other compartments to the MLN can be ignored compared with the other kinetic components mentioned above. For spleen, the number of CD8+ T cells, , is assumed to be mainly affected by proliferation in place, influx from MLN, migration to lung, and loss due to death or other mechanisms. For CD8+ T cells in lung, , direct influx from both lymph node and spleen are considered, and the loss is again due to death or other reasons. We further make the initial assumptions that the activation of CD8+ T cells that leads to expansion of the virus-specific population in both MLN and spleen is stimulated mainly by antigen-bearing dendritic cells, with negligible expansion due to proliferation in lung. Based on these tenets we formulated the following mechanistic model:

| (1) |

where Dm denotes the number of mature antigen-bearing dendritic cells in MLN, Ds the number of mature dendritic cells in spleen; τ is the time delay of the effects of dendritic cells on CD8+ T cell activation; ρm and ρs are the proliferation rates of CD8+ T cells stimulated by dendritic cells in MLN and spleen, respectively; δm, δs and δl are the loss rates in MLN, spleen and lung, respectively; γms is the migration rate from MLN to spleen, γml the migration rate from MLN to lung, and γsl the migration rate from spleen to lung. Finally, data for Ds are not available in this study or the literature to the best knowledge of the authors. Dm is thus used to replace Ds in all calculations, with the assumptions that the APC in the MLN and spleen share similar temporal patterns, but can differ in total number proportional to the size of the two organs.

We make explicit and strong assumptions in the model above. However, we recognize that numerous factors may affect CD8+ T cell trafficking after influenza virus infection and their mechanisms are not fully understood; therefore, the mechanistic model above may be oversimplified and thus not able to accurately interpret the experimental observations. We hence explore three more hypotheses: first, that the effects of other undefined factors and mechanisms that affect CD8+ T cell growth and disappearance are not negligible; second, that the rise and fall of CD8+ T cell numbers in the infection is determined by clonal expansion followed by increased programmed cell death when the pathogen is cleared, versus a constant rate of loss over the acute phase; third, that an influx of T cells from other tissue compartments such as the liver (24)could explain late increases in splenic CD8+ T cell numbers not due to proliferation (Fig. 1).

To study the first hypothesis, we consider the following model

| (2) |

where two unknown time-varying parameters κm(t) and κs(t) are introduced to replace [ρmDm(t–τ) – δm] and [ρsDs(t–τ) – δs) and should be interpreted as the net growth rates of CD8+ T cells in MLN and spleen, respectively, not distinguishing proliferation from disappearance/death. To study the second hypothesis, we introduce a time-varying loss rate of CD8+ T cell δl(t) in lung, removing the two previous unknown time varying parameters introduced in model 2, so the third model is:

| (3) |

To study the third hypothesis, we consider a time-varying flux of CD8+ T cells from other additional compartments to spleen at a nonparametric rate ηs(t), and we also keep the time-varying loss rate of CD8+ T cell δl(t) in lung. This alternative model can be written as:

| (4) |

In models (2)to (4), since the time-varying parameters do not depend on explicit assumptions about how CD8+ T cells are stimulated or disappear in spleen, we call such models “semi-mechanistic”.

All these alternative hypotheses are explored and tested from our experimental data using the statistical methods introduced below. We summarize our mathematical notations and parameter definitions in Table I.

Table 1.

Parameter/variable definitions in models (1) to (4).

| Variable/Parameter | Definition | Units | Assay | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

effector CD8+ T cells in MLN | cells per MLN | 1)ICS 2)tetramer |

1)CD8 T cells secreting any combination of TNF, IFN, IL-2 2)NP CD8+ T cells |

|

|

|

effector CD8+ T cells in spleen | cells per spleen | 1)ICS 2)tetramer |

1)CD8+ T cells secreting any combination of TNF, IFN, IL-2 2)NP CD8+ T cells |

|

|

|

effector CD8+ T cells in lung | cells per lung | 1)ICS 2)tetramer |

1)CD8+ T cells secreting any combination of TNF, IFN, IL-2 2)NP CD8+ T cells |

|

| Dm | matured Dendritic cells in MLN | cells per MLN | PNAS LacZ- inducible hybridomas for DbNP and DbPA (61) | number of DbNP366–374 specific LacZ+ cells per MLN | |

| Ds | matured Dendritic cells in spleen | cells per spleen | no data | replaced by Dm in calculation | |

| ρm | proliferation rate of effector CD8+ T cells in MLN stimulated by DC | day−1 (cells per MLN) −1 | estimated | in models (1), (3) and (4) only | |

| ρs | proliferation rate of effector CD8+ T cells in spleen stimulated by DC | day−1 (cells per spleen)−1 | estimated | in models (1), (3) and (4) only | |

| τ | lag time for DC to stimulate CD8+ T cell proliferation | day | estimated | in models (1), (3) and (4) only | |

| δm | disappearance rate of effector CD8+ T cells in MLN | day−1 | estimated | in models (1), (3) and (4) only | |

| δs | disappearance rate of effector CD8+ T cells in spleen | day−1 | estimated | in models (1), (3) and (4) only | |

| γms | migration rate of effector CD8+ T cells from MLN to spleen | day−1 | estimated | in all models | |

| γml | migration rate of effector CD8+ T cells from MLN to lung | day−1 | estimated | in all models | |

| γsl | migration rate of effector CD8+ T cells from spleen to lung | day−1 | estimated | in all models | |

| δl | disappearance rate of effector CD8+ T cells from lung | day−1 | estimated | in all models, varying in models (3) and (4) time- | |

| ηs(t) | net flux rate of effector CD8+ T cells into spleen from compartments other than MLN, spleen and lung | cells per day | estimated | in model (4) only, time-varying | |

| κm(t) | net growth rate of effector CD8+ T cells in MLN | day−1 | estimated | in model (2)only, time-varing | |

| κs(t) | net growth rate of effector CD8+ T cells in spleen | day−1 | estimated | in model (2)only, time-varing |

Statistical Methods

We performed structural and practical identifiability analysis for the four ordinary differential equation (ODE)models above before we applied statistical methods to estimate the parameters in the above ODE models (25, 26). From the structural identifiability analysis, all the parameters were found theoretically identifiable. Further, we performed practical identifiability analysis to confirm whether all the parameters are estimable from experimental data with noise using Monte Carlo simulations (25, 27, 28). Our results demonstrate that almost all the parameters are practically identifiable except for δm, δs and γml.

We estimated all the kinetic parameters including both constant and time-varying parameters as well as the delay time and the initial conditions for the ODE models from the time course data of activated CD8+ T cell numbers in MLN, spleen and lung using the nonlinear least squares method (29–32). We used a hybrid global optimization algorithm DESQP in (30)to minimize the residual sum of squares (RSS). The log-transformation and standardization of the data were used to stablize the estimation algorithm. The time-varying parameters in above models were approximated by a sum of third order B-Splines of degrees of freedom 3(33), e.g., and , so that the time-varying parameter ODE models can be transformed into standard ODE models with constant parameters (32). The number of knots and basis functions can be determined using the model selection criterion such as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)(34, 35). We used Fisher Information Matrix to calculate 95% confidence interval of the parameters.

We explore and evaluate various alternative models and model assumptions using the AIC score defined as (34, 35):

where RSS is the residual sum of squares, n is the number of observations, and k the number of unknown parameters. The AIC is a score that can be used to evaluate different models by compromising the fitting residuals and model complexity (measured by the number of parameters in the model). A smaller AIC score indicates a better model. In this study, the number of observations (n)is 180 in total (from day 5 to day 14), the number of parameters (k)is 9 in model 1, 12 in model 2, 11 in model 3, and 14 in model 4.

Some of our parameter estimations and simulations for ODE models were performed using DEDiscover, a publicly available tool developed by our Center for Biodefense Immune Modeling (https://cbim.urmc.rochester.edu/software). DEDiscover is a user-friendly modeling environment for both mathematical modelers and immunologists that provides a workflow-oriented interface and a comprehensive set of computing algorithms. In particular, to help modelers and immunologists to compare and select modeled built upon alternative assumptions, DEDiscover also reports the AIC score after modeling fitting.

Results

Model fitting to determine key cellular parameters

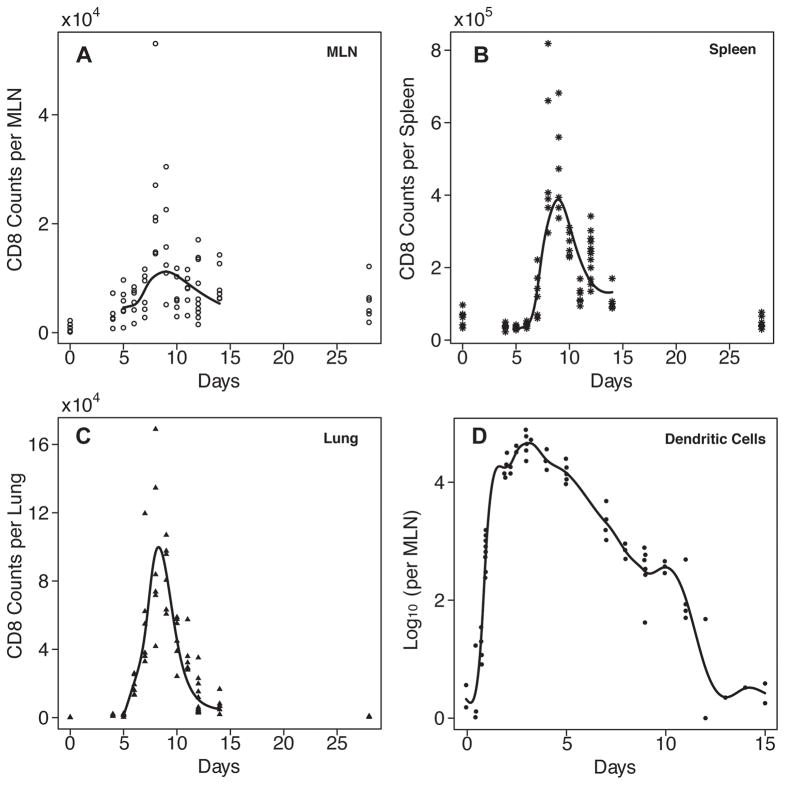

Our objective using the modeling approach is to estimate biological parameters that are difficult or impossible to measure directly. These include such processes as cell trafficking from one anatomical compartment to another, and growth of the virus-specific CD8+ T cell population. Initially we fitted model 1 to the experimental data from mice for virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the MLN, spleen, and lung. The virus specific T cells were identified and measured using an intracellular cytokine assay with live-virus restimulation, and staining for IL2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α as previously described in our original global influenza model (19). CD8+ T cells that stained positive for any combination of 1–3 cytokines were counted as positive. Prior to day 5, the difference between virus-restimulated and control cultures were close to zero and inconsistent, making it impossible to accurately fit the model to the data. In contrast, virus-specific CD8+ T cells become easily detectable from day 5 onwards by a variety of assays, including the intracellular cytokine approach (19, 24, 36–39). Therefore data from days 5 to 14 were used for the model fitting. The experimental data and the fitted curves are plotted in Figures 1 and 3, with the estimated parameters reported in Table II.

Figure 3.

Fitting results from Model 4 using parameter estimates from Table II along with the experimental data plotted (indicated by the individual symbols in each plot)against day of infection. Solid lines indicate curves predicted by the model for effector CD8+ T cells in MLN (A), spleen (B), and lung (C). Actual (individual symbols)and predicted numbers of antigen-bearing dendritic cells are shown in (D).

Table 2.

Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for parameters in four models

| Parameters | Estimates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (unit) | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) |

| TEm (5) cells per MLN | 3.96E+3 (3.65E+3,4.27E+3) | 3.24E+3 (2.91E+3, 3.58E+3) | 4.43E+3 (3.34E+3, 5.52E+3) | 4.63E+3 (3.35E+3, 5.92E+3) |

| TEs (5) cells per spleen | 3.64E+4 (3.16E+4, 4.12E+4) | 2.19E+4 (1.96E+4, 2.43E+4) | 3.49E+4 (2.33E+4, 4.64E+4) | 3.07E+4 (2.11E+4, 4.04E+4) |

| TEl (5) cells per lung | 1.31E+3 (1.05E+3, 1.58E+3) | 1.31E+3 (1.09E+3, 1.53E+3) | 1.33E+3 (7.34E+2, 1.93E+3) | 1.30E+3 (7.45E+2, 1.85E+3) |

| ρm day−1 (cells per MLN)−1 | 1.66E−5 (1.40E−5, 1.92E−5) | NA | 1.58E−5 (1.08E−5, 2.08E−5) | 1.55E−5 (4.23E−6, 2.68E−5) |

| ρs day−1 (cells per spleen) −1 | 4.48E−5 (4.22E−5, 4.74E−5) | NA | 3.59E−5 (3.40E−5, 3.78E−5) | 4.57E−5 (2.02E−5, 7.12E−5) |

| τ day | 3.08E+0 (2.80E+0, 3.35E+0) | NA | 3.53E+0 (2.42E+0, 4.64E+0) | 3.72E+0 (3.34E+0, 4.09E+0) |

| δm day−1 | 0 (dropped) | NA | 0 (dropped) | 0 (dropped) |

| δs day−1 | 0 (dropped) | NA | 0 (dropped) | 0 (dropped) |

| γms day−1 | 1.57E−1 (1.42E−1, 1.72E−1) | 1.09E+0 (1.05E+0, 1.14E+0) | 1.77E−1 (1.12E−2, 2.42E−1) | 1.84E−1 (1.32E−1, 2.36E−1) |

| γml day−1 | 0 (dropped) | 0 (dropped) | 0 (dropped) | 0 (dropped) |

| γsl day−1 | 4.95E−1 (4.67E−1, 5.23E−1) | 4.18E+0 (3.91E+0, 4.45E+0) | 3.52E−1 (2.75E−1, 4.28E−1) | 5.99E−1 (3.64E−1, 8.34E−1) |

| δl day−1 | 3.96E+0 (3.52E+0, 4,40E+0) | 3.15E+1 (3.07E+1, 3.23E+1) | Varies with time see fig. 4 | Varies with time see fig. 4 |

| ηs(t) cells per day | NA | NA | NA | Varies with time see fig. 4 |

| κm(t) day−1 | NA | Varies with time see fig. 4 | NA | NA |

| κs(t) day−1 | NA | Varies with time see fig. 4 | NA | NA |

| RSS | 15.77 | 14.59 | 11.48 | 10.85 |

| AIC | −420.29 | −428.27 | −473.40 | −477.59 |

Growth/Loss Rates from Mechanistic Model (Model 1)

In the mechanistic model (Model 1, Methods), we make the assumption that the expansion of CD8+ T cells in both MLN and spleen is mainly a consequence of antigen presentation analogous to mature antigen bearing dendritic cells that can activate naïve T cells. We also allow a time delay for stimulation of T cell expansion, the length of which is unknown but can be estimated from data. The concentrations of dendritic cells in MLN and spleen are based on the two different parameters ρm and ρs in our model. In more explicit terms, our assumptions are that: 1)the stimulation strength for activation and growth of the virus-specific CD8+ T cell population is proportional to the number of dendritic cells; and 2)the temporal patterns of stimulation in MLN and spleen are similar, but the numbers can be very different based on the size of the organs. Based on these assumptions, we fit this model and the results are summarized in Table II. Both the residual sum of squares (15.77)and AIC score (−420.29)of this model are the largest compared to the other three models, which suggests that this mechanistic model does not fit the data as well, possibly due to an oversimplification of the model assumptions or omission of key biological parameters included in the alternative models.

The estimated dendritic cell/APC-dependent effector CD8+ T cell population expansion rates for MLN and spleen, ρmDm(t–τ) and ρsDs(t–τ), respectively have peak values of 1.3 day−1 and 3.5 day−1 at around day 7, corresponding to a doubling time of 12 hours and 4.8 hours. This suggests that the growth of the virus-specific CD8+ T cell population in spleen is approximately 2-fold greater than that in the MLN. Similar conclusions were drawn from the results derived from models 3 and 4 described below (see Table II and Fig. 4).

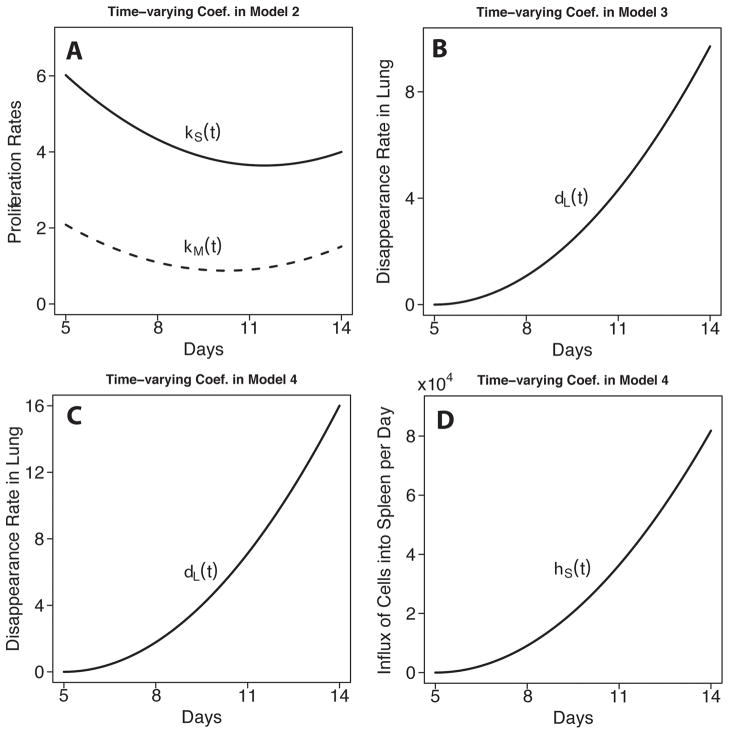

Figure 4.

Plots of estimated time-varying parameters for growth of the effector CD8+ T cell populations in spleen and MLN in model 2 (A); disappearance of effectors in the lung in model 3 (B)and model 4 (C); and the influx of effector CD8+ T cells from other compartments in model 4 (D).

The time delay for stimulation of T cell expansion by dendritic cells is calculated as 3.08 days, matching well with direct measurements in the literature (40–43). The estimates of the migration rates of effector CD8+ T cells from MLN to spleen and from spleen to lung, γms and γsl, are 0.16 day−1 and 0.5 day−1, respectively, which suggests that migration from spleen to lung is substantial. The constant loss rate of effector CD8+ T cells from the lung, δl, could be reliably (p < 0.001)estimated at ~ 4 day−1, corresponding to a half-life of 4.2 hours. However, it was not possible to reliably determine the values for the constant loss rates (δm and δs)of CD8+ effectors from the MLN and spleen, or the migration rate of activated CD8+ T cells from MLN to lung (γml). This is due to the fact that the estimated parameter values are low and close to zero, and because of this may be (statistically)obscured by noise in the data set.

Estimation of the growth rate of effector CD8+ T cells

Since it is difficult to directly measure or estimate explicit values for cell loss other than migration in the MLN and spleen, in model 2 we considered an alternative model in which we introduce combined terms for both cell proliferation and loss as the time-varying pure growth rates, κm(t) and κs(t). The estimates of these two parameters are plotted in Fig. 4. Model 2 makes no assumptions on the patterns and magnitudes of the two time-varying parameters km (t) and ks (t). That is, we did not make an explicit assumption of what factors regulate the expansion of the CD8 effector population. We believe this approach has its advantages especially when some mechanisms are not completely clear. The patterns of κm(t) and κs(t) are similar to one another but, as with the population growth rates estimated in the first model, the value of κs(t) is more than 2-fold greater than κm(t), which suggests a noticeably faster net generation of effector CD8+ T cells in the spleen than in MLN. For MLN, κm(t) decreases from 2.1 day−1 at day 5 to 0.9 day−1 at around day 10; for spleen, κs(t) decreases from 6.0 day−1 at day 5 to 3.6 day−1 at around day 12. The corresponding maximum doubling times of the virus-specific CD8+ T cell populations in MLN and spleen are 8 hours and 2.8 hours, respectively, which are more than 30% more rapid than the estimated doubling times in model 1 (at 12 hours and 4.8 hours in MLN and spleen, respectively). Therefore, it is likely that factors important to the expansion of the effector CD8+ T cell population in MLN and spleen are missing from model 1. The smaller AIC score for model 2 than model 1 (−428.27 vs. − 420.29)reinforced this interpretation indicating that model 2 is a better fit to the data. Also note that the short doubling time in the spleen suggests additional factors at work, such as the contribution of other compartments to the growth rate. This is considered explicitly below.

However, the estimated migration rates from MLN to spleen and from spleen to lung, as well as the disappearance rate in lung (1.1 day−1, 4.2 day−1 and 32 day−1, respectively)are all an order of magnitude higher in model 2, raising questions about the accuracy of these estimates. The high values could be due to the strong correlations between the proliferation parameters and the migration and disappearance rates.

Estimates of effector CD8+ T cell migration and disappearance

Next, the parameters for cell trafficking and constant (Model 1 & 2)or time-varying death or loss (Model 3)were estimated. These constant loss rates represent the disappearance of cells from the system due to death or physical removal (sloughing or phagocytosis), which cannot be easily resolved from one another, are treated as a single term. As mentioned earlier, in comparison to other parameters, the estimates for the constant pure loss rates for MLN and spleen, δm and δs, were essentially zero and could not be reliably determined. Similarly, the migration rate of virus-specific CD8+ T cells from MLN to lung, γml, was also estimated as close to zero. A low AIC score for models in which these parameters are excluded, indicating a good fit, reinforces the conclusion that these rates have a minimal impact on the fidelity of the model and the behavior of the system.

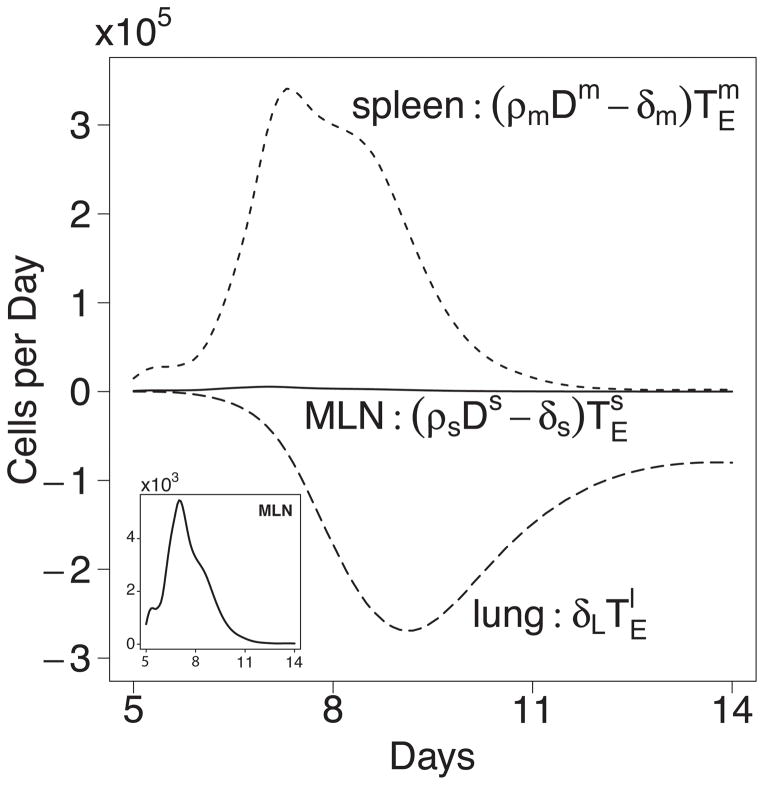

Interestingly, when we change the constant disappearance rate δl in lung in model 1 to time-varying δl (t) as in model 3, the fit of the model to the data improved further, and AIC score decreased from − 420.29 to − 473.40, which suggests the pattern of cell loss in lung cannot be simplified as a constant over time. Instead, the estimated time trajectory of δl (t) is plotted in Fig. 4B, which shows that the disappearance rate δl (t) of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in lung monotonically increases from 0 at day 5 to 9.7 day−1 at day 14. The shortest half-life of CD8+ T cells therefore occurs at day 14 with a value about 2 hours, demonstrating an increase in the rate of effector cell loss at the end of the immune response.

Collectively, these results suggest increased effector cell clearance towards the end of the acute response, particularly in the lung. In addition, there is a strong indication that the spleen plays a much more substantial role in the overall CD8+ T cell response to the infection than may have been previously appreciated.

Modeling the contribution of other tissues

In contrast to the growth of the virus-specific CD8+ T cell population, T cell trafficking into peripheral tissues is an antigen-independent process (44, 45). Activated T cells that enter the circulation have the ability to traffic to many tissues other than the site of infection in the lung (46, 47). Because T cell migration through peripheral tissues is dynamic and continuous, and assuming some T cells pass through the tissues and re-enter the circulation via the lymphatics, we investigated the contribution of influx of activated CD8+ T cells from compartments other than the three we considered. To accomplish this, model 4 was developed that included an additional compartment corresponding to all other tissue sites combined (see model 4, Methods). Also, as suggested by model 3, we retain the time-varying disappearing parameter δl (t) in lung. The fitting results suggest that a time-varying influx ηs (t)from other tissues to spleen is significant, contributing a maximum of 8.2×104 cells per day. Also, the estimates of all other constant parameters are very close to the estimates from models 1 and 3, suggesting that unlike model 2, the introduction of the two time-varying parameters in model 4 do not affect the estimates of other constant parameters and the results are therefore reliable. The smallest AIC score (− 477.59)also suggest that model 4 is superior to all other three models. Such results suggest that it is very likely that there exists a significant, time-varying influx of CD8+ T cells from other tissues to spleen; also, the rate of disappearance of effector CD8+ T cells in lung should be monotonically increasing (see Fig. 4). For convenience, we plotted the product of δl (t) and in Fig. 5. We see that the number of cell lost per day increases from 0 at day 5 to 2.7×105 cells per day at day 9, and then decreases down to 8×104 cells per day at day 14. These results suggest that sites other than the MLN and spleen are making substantial contributions to the effector CD8+ T cell pool, and moderate the obvious contributions of the spleen as a sole organ. Instead, these results are consistent with the view that, in addition to in situ expansion, the spleen may collect effector T cells in the circulation that have come from other tissues. These findings do not diminish the conclusion that cells from the spleen substantially contribute to the response in the lung.

Figure 5.

Net population growth/loss rates at different sites. Estimated number of cells gained or lost per day in MLN, spleen, or lung using model 4 and the parameters from Table II. Results for MLN are also plotted on a two log lower (103 vs 105)scale in the inset to better visualize the change in growth rate over time.

Discussion

We have developed ordinary and time-delay ordinary differential equations (ODE or TD-ODE)to model the population growth, trafficking, and loss of virus-specific CD8+ T cells in MLN, spleen and lung in mice with primary influenza A infection. These models allowed us to challenge various assumptions and test hypotheses about how the system works. In addition, the model fitting process generated estimates of several key biological parameters that are technically difficult or impossible to measure empirically. Several assumptions that were held prior to the start of this work proved difficult to justify in the models. In particular, the role of the spleen in the primary CD8+ T cell response to influenza infection may be more significant than previously thought.

There is a widely held view that during a primary influenza infection, the development of the virus-specific CD8+ T cell response occurs in the following sequential fashion: dendritic cells bearing viral antigens migrate from the lung to the draining mediastinal lymph node where they activate naïve virus-specific T cells. The T cells proliferate in the MLN and then leave the lymph node to enter the blood, appearing next in the lung after extravasation (24, 48–51). This whole process takes 4–5 days before virus-specific CD8+ T cells can be detected at any one site. Very careful measurements made with sensitive techniques such as MHC class I tetramer staining (24, 36)during the very early phase of the acute response (days 0–6), support this general view (24, 51–53). However, these approaches only tell us where the T cells first become detectable, not where they came from. Nor do they consider the relative sizes of the T cell populations in each site, or the population growth and trafficking rates that would be required for the MLN to be the major source of effectors. Nevertheless, when looking at such data, the earliest tetramer+ CD8+ T cells can be detected in the MLN at day 4–5, then appear simultaneously in the lung, spleen, and organs such as the liver at 5–6 days (24, 52, 53). After this point, the numbers of cells at each site rises very rapidly, presumably driven by a combination of proliferation and migration, with little initial loss. Unfortunately, these major contributing biological parameters and sites become hard to experimentally deconvolute through empirical observations. The various rates of activation, proliferation, migration and death are difficult to measure directly and are often confounded by the difficulty to experimentally distinguish whether, for example, a T cell that has upregulated Ki67, diluted its CFSE label, or incorporated BrdU did so in the compartment that was sampled, or another site the T cell just came from (54, 55). However, by comparing alternative models through a process of fitting, we can resolve some of the factors.

We developed four models and compared them using mainly the AIC score. It is possible for two models to have close scores (e.g., model 3 vs. model 4); however, as suggested by Burnham (35), the difference instead of the absolute value of AIC score matters. Even a small decrease in AIC scores will still suggest superiority in model structures. In this study, the model that produced both the best fit to the experimental observations and the best AIC score is model 4. In this model, the expansion of the CD8+ effector T cell population is dependent on the number and kinetics of the professional, antigen-bearing APCs rather than the viral load. The effector CD8+ T cell populations expand in both the draining MLN and the spleen, but the spleen is estimated to make a much larger contribution to the pool of cells that migrate to the lung. Because cell loss in these sites is estimated to be very low, the size of the T cell population in the spleen, in turn is likely dependent upon a combination of factors that include in situ proliferation, and an influx of T cells from other tissue compartments. These other compartments would include cells returning to the circulation from peripheral non-lymphoid tissues not infected with the virus, but may also include lymphoid organs such as the cervical lymph nodes and bone marrow that have the capacity to contribute to the virus-specific T cells response (53, 56–58), but were not explicitly considered in our modeling or the experimental data set. Alternatively, the growth of the CD8+ T cell numbers in the spleen could also include those cells that were activated to proliferate outside of the spleen, but continued a program of cell division (59). Other factors such as the local cytokine environment to promote T cell expansion were also not explicitly modeled, though such effects should still be proportional to the dendritic cell kinetics as suggested though our model fitting.

In addition to a time-varying term for the contribution of other sources of T cells to the spleen, the best fit to the data was provided by the models with a time varying loss rate for the effector T cells, with values increasing towards the end of the acute response, and highest in the lung. Models with constant rates of cell loss did not reliably reflect the experimental data. Regardless, effector CD8+ T cell loss rates from the MLN and spleen were estimated to be very low and close to zero compared with other parameters. These results suggest that T cell survival factors that include antigen or cytokines must wane towards the end of the response. It is also possible that the features unique to influenza infection of the lung, such as the epithelial site of infection and effector cell trafficking into the mucosa drive some of these effects.

A notable advantage of time-varying parameters is that uncertainties in mechanisms can be well accounted for. Although this approach usually requires frequent time-course data, it could be the only right choice for complex dynamic problems. For example, although the introduction of one time-varying parameter will result in 3 more constant parameters in our models, the overall performance measured by AIC scores of time-varying parameter models still outperformed model 1 which has only constant parameters. In more than one of the models, we found that the growth rate of the virus-specific, effector CD8+ T cell population in spleen is twice as large as that in MLN, and both the experimental data and fitted-model simulations indicate that the MLN precedes the spleen by about one day. Furthermore, the numbers of cells and rate of accumulation in the spleen and the lung cannot be solely explained by proliferation in, and/or migration from the MLN, suggesting that the MLN is not the sole source of anti-viral effectors. Direct migration from the MLN to the lung and death rates in the MLN and spleen were all estimated to be very small relative to other contributors. Combined, these estimates support that the system operates differently than we originally assumed.

The finding of a minimal contribution of effector CD8+ T cell migration from MLN to the growth of this population in the lung deserve some qualification. These results do not imply that CD8+ T cells do not traffic from the MLN to the lung, nor do they change the view that the adaptive response is initiated in the draining lymph node. Instead, these estimates should be viewed in consideration of the entire systemic response, the relative sizes of the virus-specific T cell populations at each site over time, and in comparison to the rates of cell migration and accumulation in sites other than the lung. For example, the numbers of virus-specific effector CD8+ T cells at day 5, TEm (5), TEs(5), and TEl (5)in model 3, are estimated as 4.4×103, 3.5×104, and 1.3×103 cells per MLN, spleen, and lung, respectively; the spleen being an order of magnitude above the other sites. Shortly after virus-specific CD8+ T cells become detectable in the system, the spleen becomes the major reservoir of these cells, and the distribution cannot be mathematically explained by growth and trafficking of the virus-specific effector population from the MLN alone. In contrast, the migration rates of activated CD8+ T cells from MLN to spleen and from spleen to lung in models 1, 3 and 4 are all larger than from MLN to lung, and close to each other at around 0.2 day−1 and 0.5 day−1, respectively.

This means is that although common sense suggests that some of the cells must come directly from the MLN, in fact the contribution of this source is very small and primarily observable very early in the response when cell numbers are low. Later in the response, the only way to compensate would be to impose extraordinarily high cell growth and migration rates for the MLN.

The picture that emerges fits with observations made by Masopust, Reinhardt, and Marshall in 2001 showing that activated effector T cells traffic all over the body, and not just to the sites of infection (46, 47, 53). Experiments in which the MLN is carefully digested with enzymes to liberate T cells complexed to APC (60)do not change the values enough to alter this conclusion. This view is less controversial when considering that the spleen can function as a site of primary immunity under conditions that disrupt trafficking of naïve T cells into the lymph nodes (56–58, 61). The original experiments, performed over a decade ago, demonstrated a more than 10-fold decrease in virus-specific CTL (and T helper precursors)in the lung in mice that had been splenectomized (56). The conclusions about the role of the spleen stand in contrast to early reports of experiments with splenectomized mice that concluded the spleen made little contribution to the infection (62). A more likely interpretation is that splenectomy does not affect control of mild influenza infection because there are more than enough CTL generated to control the virus. This is consistent with the observation that the absence of a spleen reduces the total number of CD8+ T cells generated.

One of the valuable features of modeling and simulation is the ability to explicitly explore alternative hypotheses and model structures. For example, we compared two models in which the T cell response was driven by either the amount of virus in the system (results not shown), or the number of professional, antigen-bearing APC (DC or D as termed here). The DC driven model provided a substantially, and statistically better, fit to the actual experimental data. This suggests that the kinetics and magnitude of the CD8+ T cell response is limited more by the number of APC available than the amount of antigen.

Several other key parameters were estimated from the models. These include the growth and disappearance of T cells in different compartments. In model 4, the growth rates (ρmDm(t–τ) in MLN and ρsDs(t–τ) in spleen)increased rapidly between days 5 and 7, and then dropped with the decrease in DC to reach a minimum around day 13 (Fig. 3). The maximum population doubling time in the MLN was about 20 hours, and the spleen followed a similar pattern but was estimated to have a maximum doubling time of 6.9 hours, or approximately 3.5 doublings per day. This is significantly slower than other cell-based estimates that range from as high as 5.3 to 12 cell divisions per day (40), but lower than others that estimate of 17–19h per division (63). These discrepancies may be accounted for by differences in population growth rates versus cell division rates.

There is also recent evidence that proliferation of CD8+ T cells occurs in the lung itself (54, 64), but this was not initially considered in our models. However, if we explicitly explore the hypothesis that the T cells proliferate in the lung by adding the term ρl, then the death and proliferation rates in lung δl become so strongly correlated such that we cannot distinguish them from each other using this model and data set. Even when the proliferation rate in the lung is fixed to some value, only the estimate of the death rate in lung was affected. That is, the proliferation rate in lung cannot be determined separately based on current models and data. Therefore, we did not explicitly include the term for proliferation in the lung in our model. Instead, the parameter δl is, in effect, the net of the proliferation and disappearance rates for CD8+ cells in lung. The possibility of cell proliferation in the lung does not negate the conclusion that the spleen and other sites are a major contributor to the overall CD8+ T cell response. Migration of T cells that have proliferated in the lung back to the MLN or spleen is likely to be very small or negligible. Furthermore, although evidence of CD8+ T cell proliferation in the lung exists, it makes a substantial but not complete contribution to the total number of CD8+ T cells in the lung and seems to contribute the most at early time points in the infection (54).

Interestingly, the lung was the only site in which cell loss, presumably due to death and other factors, was estimated to be time varying with a maximum value 9.7 per day, or a half-life of 1.7 hours. The number of cells lost per day reached its maximum around day 9 (2.7×105 cells per day, see Fig. 5). This is not out of line with the notion that continued encounter with antigen-bearing target cells, and migration out into the infected airways (from which there is no return)account for a significant disappearance of the effector cells. If the cells in the lung were also proliferating as has been postulated, then the actual loss rate would have to be higher still. Keep in mind however that we treated cell loss as a time-varying parameter instead of a constant one. We believe our modeling methods and techniques can provide a more powerful platform for immunologists to understand viral and immune system dynamics.

Collectively, these efforts change the way the immune response to influenza infection is viewed. The spleen can no longer be considered as a location used merely to contain the ‘spillover’ of excess virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the blood that were generated in the MLN and not taken up by the lung or other tissues. Instead, the spleen is a major contributor of effector CD8+ T cells against the virus infection. This view also implies that the spleen contains antigen-bearing APC that can drive T cell proliferation, and is an environment where T cell expansion can occur. As such it may also be an important source of the memory T cells that remain at the end of the acute immune response.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram depicting pathways of CD8+ T cell migration among three compartments.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the excellent and dedicated technical support of Tina Pellegrin and Joe Hollenbaugh during the murine experiments.

Footnotes

This work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases contract HHSN272201000055C and R01 AI069351 (MZ). Portions of this work were done under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC52-679 06NA25396 (ASP).

References

- 1.Doherty PC, Topham DJ, Tripp RA, Cardin RD, Brooks JW, Stevenson PG. Effector CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell mechanisms in the control of respiratory virus infections. Immunol Rev. 1997;159:105–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topham DJ, Tripp RA, Doherty PC. CD8+ T cells clear influenza virus by perforin or Fas-dependent processes. J Immunol. 1997;159:5197–5200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topham DJ, Doherty PC. Clearance of an influenza A virus by CD4+ T cells is inefficient in the absence of B cells. J Virol. 1998;72:882–885. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.882-885.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castrucci MR, Kawaoka Y. Biologic importance of neuraminidase stalk length in influenza A virus. J Virol. 1993;67:759–764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.759-764.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao P, Watanabe S, Ito T, Goto H, Wells K, McGregor M, Cooley AJ, Kawaoka Y. Biological heterogeneity, including systemic replication in mice, of H5N1 influenza A virus isolates from humans in Hong Kong. J Virol. 1999;73:3184–3189. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3184-3189.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tumpey TM, Basler CF, Aguilar PV, Zeng H, Solorzano A, Swayne DE, Cox NJ, Katz JM, Taubenberger JK, Palese P, Garcia-Sastre A. Characterization of the reconstructed 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic virus. Science. 2005;310:77–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1119392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazarowitz SG, Choppin PW. Enhancement of the infectivity of influenza A and B viruses by proteolytic cleavage of the hemagglutinin polypeptide. Virology. 1975;68:440–454. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun X, Tse LV, Ferguson AD, Whittaker GR. Modifications to the hemagglutinin cleavage site control the virulence of a neurotropic H1N1 influenza virus. J Virol. 84:8683–8690. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00797-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belz GT, Smith CM, Kleinert L, Reading P, Brooks A, Shortman K, Carbone FR, Heath WR. Distinct migrating and nonmigrating dendritic cell populations are involved in MHC class I-restricted antigen presentation after lung infection with virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8670–8675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402644101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belz GT, Smith CM, Eichner D, Shortman K, Karupiah G, Carbone FR, Heath WR. Cutting edge: conventional CD8 alpha+ dendritic cells are generally involved in priming CTL immunity to viruses. J Immunol. 2004;172:1996–2000. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bocharov GA, Romanyukha AA. Mathematical model of antiviral immune response. III. Influenza A virus infection. J Theor Biol. 1994;167:323–360. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1994.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AM, Perelson AS. Influenza A virus infection kinetics: quantitative data and models. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010 doi: 10.1002/wsbm.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perelson AS. Modelling viral and immune system dynamics. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:28–36. doi: 10.1038/nri700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handel A, Antia R. A simple mathematical model helps to explain the immunodominance of CD8 T cells in influenza A virus infections. J Virol. 2008;82:7768–7772. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00653-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beauchemin C, Samuel J, Tuszynski J. A simple cellular automaton model for influenza A viral infections. J Theor Biol. 2005;232:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohler L, Flockerzi D, Sann H, Reichl U. Mathematical model of influenza A virus production in large-scale microcarrier culture. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;90:46–58. doi: 10.1002/bit.20363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baccam P, Beauchemin C, Macken CA, Hayden FG, Perelson AS. Kinetics of influenza A virus infection in humans. J Virol. 2006;80:7590–7599. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01623-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hancioglu B, Swigon D, Clermont G. A dynamical model of human immune response to influenza A virus infection. J Theor Biol. 2007;246:70–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HY, Topham DJ, Park SY, Hollenbaugh J, Treanor J, Mosmann TR, Jin X, Ward BM, Miao H, Holden-Wiltse J, Perelson AS, Zand M, Wu H. Simulation and prediction of the adaptive immune response to influenza A virus infection. J Virol. 2009;83:7151–7165. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00098-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miao H, Hollenbaugh JA, Zand MS, Holden-Wiltse J, Mosmann TR, Perelson AS, Wu H, Topham DJ. Quantifying the early immune response and adaptive immune response kinetics in mice infected with influenza A virus. J Virol. 2010;84:6687–6698. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00266-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belz GT, Behrens GM, Smith CM, Miller JF, Jones C, Lejon K, Fathman CG, Mueller SN, Shortman K, Carbone FR, Heath WR. The CD8alpha(+)dendritic cell is responsible for inducing peripheral self-tolerance to tissue-associated antigens. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1099–1104. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belz GT, Carbone FR, Heath WR. Cross-presentation of antigens by dendritic cells. Crit Rev Immunol. 2002;22:439–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belz GT. Direct ex vivo activation of T cells for analysis of dendritic cells antigen presentation. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;595:351–369. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-421-0_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polakos NK, Klein I, Richter MV, Zaiss DM, Giannandrea M, Crispe IN, Topham DJ. Early intrahepatic accumulation of CD8+ T cells provides a source of effectors for nonhepatic immune responses. J Immunol. 2007;179:201–210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miao H, Xia X, Perelson AS, Wu H. On identifiability of nonlinear ODE models with applications in viral dynamics. SIAM Review. 2011;53 doi: 10.1137/090757009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia X, Moog CH. Identifiability of nonlinear systems with application to HIV/AIDS models. Automatic Control, IEEE Transactions on. 2003;48:330–336. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miao H, Dykes C, Demeter LM, Cavenaugh J, Park SY, Perelson AS, Wu H. Modeling and estimation of kinetic parameters and replicative fitness of HIV-1 from flow-cytometry-based growth competition experiments. Bull Math Biol. 2008;70:1749–1771. doi: 10.1007/s11538-008-9323-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miao H, Dykes C, Demeter LM, Wu H. Differential Equation Modeling of HIV Viral Fitness Experiments: Model Identification, Model Selection, and Multimodel Inference. Biometrics. 2009;65:292–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Wu H. Estimation of time-varying parameters in deterministic dynamic models with application to HIV infections. Statistica Sinica. 2008;18:987–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang H, Miao H, Wu H. Estimation of constant and time-varying dynamic parameters of HIV infection in a nonlinear differential equation model. Annals of Applied Statistics. 2010;4:460–483. doi: 10.1214/09-AOAS290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang H, Wu H. Parameter estimation for differential equation models using a framework of measurement error in regression model. J American Statistical Assoc. 2008;103:1570–1583. doi: 10.1198/016214508000000797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xue H, Miao H, Wu H. Sieve estimation of constant and time-varying coefficients in nonlinear ordinary differential equation models by considering both numerical error and measurement error. Annals of Statistics. 2010;38:2351–2387. doi: 10.1214/09-aos784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Boor C. A Practical Guide to Splines. Springer-Verlag Berlin and Heidelberg GmbH & Co. K; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likehood principle. In: Petrov B, Csáki F, editors. Second International Symposium on Information Theory. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó; 1973. pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods Research. 2004;33:261–304. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flynn KJ, Belz GT, Altman JD, Ahmed R, Woodland DL, Doherty PC. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells in primary and secondary influenza pneumonia. Immunity. 1998;8:683–691. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flynn KJ, Riberdy JM, Christensen JP, Altman JD, Doherty PC. In vivo proliferation of naive and memory influenza-specific CD8(+)T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8597–8602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tripp RA, Hou S, McMickle A, Houston J, Doherty PC. Recruitment and proliferation of CD8+ T cells in respiratory virus infections. J Immunol. 1995;154:6013–6021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tripp RA, Lahti JM, Doherty PC. Laser light suicide of proliferating virus-specific CD8+ T cells in an in vivo response. J Immunol. 1995;155:3719–3721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoon H, Kim TS, Braciale TJ. The cell cycle time of CD8+ T cells responding in vivo is controlled by the type of antigenic stimulus. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.D’Souza WN, Lefrancois L. IL-2 is not required for the initiation of CD8 T cell cycling but sustains expansion. J Immunol. 2003;171:5727–5735. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D’Souza WN, Schluns KS, Masopust D, Lefrancois L. Essential role for IL-2 in the regulation of antiviral extralymphoid CD8 T cell responses. J Immunol. 2002;168:5566–5572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitmire JK, Benning N, Whitton JL. Precursor frequency, nonlinear proliferation, and functional maturation of virus-specific CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:3028–3036. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Topham DJ, Castrucci MR, Wingo FS, Belz GT, Doherty PC. The role of antigen in the localization of naive, acutely activated, and memory CD8(+)T cells to the lung during influenza pneumonia. J Immunol. 2001;167:6983–6990. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chapman TJ, Castrucci MR, Padrick RC, Bradley LM, Topham DJ. Antigen-specific and non-specific CD4(+)T cell recruitment and proliferation during influenza infection. Virology. 2005;340:296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masopust D, Vezys V, Marzo AL, Lefrancois L. Preferential localization of effector memory cells in nonlymphoid tissue. Science. 2001;291:2413–2417. doi: 10.1126/science.1058867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reinhardt RL, Khoruts A, Merica R, Zell T, Jenkins MK. Visualizing the generation of memory CD4 T cells in the whole body. Nature. 2001;410:101–105. doi: 10.1038/35065111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allan W, Tabi Z, Cleary A, Doherty PC. Cellular events in the lymph node and lung of mice with influenza. Consequences of depleting CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1990;144:3980–3986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Butcher EC, Picker LJ. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Topham DJ, Doherty PC. Longitudinal analysis of the acute Sendai virus-specific CD4+ T cell response and memory. J Immunol. 1998;161:4530–4535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawrence CW, Ream RM, Braciale TJ. Frequency, specificity, and sites of expansion of CD8+ T cells during primary pulmonary influenza virus infection. J Immunol. 2005;174:5332–5340. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lawrence CW, Braciale TJ. Activation, differentiation, and migration of naive virus-specific CD8+ T cells during pulmonary influenza virus infection. J Immunol. 2004;173:1209–1218. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marshall DR, Turner SJ, Belz GT, Wingo S, Andreansky S, Sangster MY, Riberdy JM, Liu T, Tan M, Doherty PC. Measuring the diaspora for virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6313–6318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101132698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McGill J, Legge KL. Cutting edge: contribution of lung-resident T cell proliferation to the overall magnitude of the antigen-specific CD8 T cell response in the lungs following murine influenza virus infection. J Immunol. 2009;183:4177–4181. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dolfi DV, Duttagupta PA, Boesteanu AC, Mueller YM, Oliai CH, Borowski AB, Katsikis PD. Dendritic cells and CD28 costimulation are required to sustain virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses during the effector phase in vivo. J Immunol. 2011;186:4599–4608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tripp RA, Topham DJ, Watson SR, Doherty PC. Bone marrow can function as a lymphoid organ during a primary immune response under conditions of disrupted lymphocyte trafficking. J Immunol. 1997;158:3716–3720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Di Rosa F, Pabst R. The bone marrow: a nest for migratory memory T cells. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feuerer M, Beckhove P, Garbi N, Mahnke Y, Limmer A, Hommel M, Hammerling GJ, Kyewski B, Hamann A, Umansky V, Schirrmacher V. Bone marrow as a priming site for T-cell responses to blood-borne antigen. Nat Med. 2003;9:1151–1157. doi: 10.1038/nm914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mercado R, Vijh S, Allen SE, Kerksiek K, Pilip IM, Pamer EG. Early programming of T cell populations responding to bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2000;165:6833–6839. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maxwell JR, Rossi RJ, McSorley SJ, Vella AT. T cell clonal conditioning: a phase occurring early after antigen presentation but before clonal expansion is impacted by Toll-like receptor stimulation. J Immunol. 2004;172:248–259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lund FE, Partida-Sanchez S, Lee BO, Kusser KL, Hartson L, Hogan RJ, Woodland DL, Randall TD. Lymphotoxin-alpha-deficient mice make delayed, but effective, T and B cell responses to influenza. J Immunol. 2002;169:5236–5243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yap KL, Ada GL. Cytotoxic T cells in the lungs of mice infected with an influenza A virus. Scand J Immunol. 1978;7:73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1978.tb00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Veiga-Fernandes H, Walter U, Bourgeois C, McLean A, Rocha B. Response of naive and memory CD8+ T cells to antigen stimulation in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:47–53. doi: 10.1038/76907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dolfi DV, Duttagupta PA, Boesteanu AC, Mueller YM, Oliai CH, Borowski AB, Katsikis PD. Dendritic Cells and CD28 Costimulation Are Required To Sustain Virus-Specific CD8+ T Cell Responses during the Effector Phase In Vivo. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;186:4599–4608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]