Abstract

CD8 exhaustion mediated by inhibitory PD-1-PD-L1 pathway occurs in several chronic infections including toxoplasmosis. While blockade of PD-1-PD-L1 pathway revives this response, the role of co-stimulatory receptors involved in this rescue has not been ascertained in any model of CD8 exhaustion. This is the first report which demonstrates that one such co-stimulatory pathway, CD40-CD40L, plays a critical role during rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells. Blockade of this pathway abrogates the ameliorative effects of αPD-L1 treatment on CD8 T cells. Additionally, this is the first report which demonstrates, in an infectious disease model, that CD8 intrinsic CD40 signaling is important for optimal CD8 polyfunctionality, proliferation, T-bet upregulation and IL-21 signaling, albeit in the context of CD8 rescue. The critical role of CD40 during the rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells may provide a rational basis for designing novel therapeutic vaccination approaches.

CD8 exhaustion as reported in chronic viral and tumor models involves a hierarchical loss of functions (cytokine, proliferation, cytotoxicity) and in extreme cases CD8 T cells can be physically deleted in a PD-1 dependent manner (1). A recently published study from our laboratory demonstrates that CD8T cells from chronically infected mice exhibit progressive functional exhaustion, concomitant with increased PD-1 expression, in the Toxoplasma model (2). This dysfunction results in reactivation of latent toxoplasmosis leading to host mortality. In vivo blockade of PD-1 interaction with its receptor PD-L1, preferentially reinvigorates pre-existing PD-1 expressing CD8 T cells, thereby preventing disease recrudescence and host mortality (2). Apart from TCR signal and cytokine milieu, one of the most important factors governing CD8 response is the balance between positive signals from co-stimulatory receptors and the negative signals from inhibitory receptors (3). It has been postulated that interplay between signals from co-stimulatory and inhibitory receptors may play an important role in T cell activation, differentiation, effector function and exhaustion (4). However, the role of co-stimulatory receptors during the rescue of this response has not been explored in any model of CD8 exhaustion. Therefore we hypothesized that blockade of inhibitory PD-1-PD-L1 pathway in chronically infected mice would lead to upregulation of co-stimulatory receptors and such positive signals would be critical for the rescue of dysfunctional CD8 T cells. We identified CD40 as one of the molecules highly upregulated on CD8 T cells in αPD-L1 treated chronically infected mice. A previous report using HY-TCR transgenic model demonstrated that CD8 intrinsic CD40 signaling is critical for memory generation (5). However, this notion has been challenged by multiple studies in infectious disease models where CD40 deficient memory CD8 T cells has been shown to elicit a normal immune response in a CD40 sufficient environment (6). Similarly in the Toxoplasma model, CD40-CD40L pathway has been shown to play a minimal role in T cell response development (7). This discrepancy in CD40 dependence has been attributed to the nature of antigen and the highly inflammatory conditions associated with infectious disease (6). However, the role of CD40-CD40L pathway during rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells has not been addressed in any model.

The current report demonstrates that CD40-CD40L pathway has minimal effect on CD8 T cell response during chronic toxoplasmosis. Surprisingly, co-administration of both αPD-L1 and αCD40L abrogates αPD-L1mediated rescue, suggesting that positive co-stimulatory signals play a pivotal role during the rescue process. Additionally, we demonstrate for the first time in an infectious disease model that CD40 plays a CD8 intrinsic role, not only in terms of quantum but quality of the immune response, albeit in the context of reinvigoration of CD8 response. Moreover, this is the first report which demonstrates that CD40 plays a strictly T cell intrinsic role in modulating the IL-21-IL21R pathway which has been shown to be important for ameliorating CD8 exhaustion in viral models of chronic infection (8).

Materials and Methods

Mice, infection and chimera generation

Age matched female C57BL/6, CD90.1, CD45.1, CD8−/− and CD40−/− mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute or Jackson Laboratory. Mixed bone marrow chimeras were generated by injecting equal number of bone marrow cells from CD90.1 and CD40−/− mice into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipients. Chimeras were infected at 8 weeks post reconstitution. Mice were infected with 10 cysts of Toxoplasma gondii (ME49) via oral route and sacrificed at week 7 pi.

In vivo and in vitro antibody treatment

Mice were injected with αPD-L1 (0.2 mg/mouse, MIH5, in house) and/or αCD40L (0.5 mg/mouse, MR1, BioXCell) every third day i.p. starting at week 5 post infection (pi) for 2 weeks. Relevant isotype controls were used throughout. Agonistic CD40 (FGK4.5, BioXCell) was used in vitro at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml for 6 h at 37°C.

Tissue preparation and flow cytometry

Single cell suspension preparation, restimulation and flow cytometry was performed as previously described (2). Briefly, surface staining for 30min at 4°C was followed by intracellular staining where needed using BD Fix/Perm Kit as per manufacturer’s protocol. Live/Dead Aqua (Invitrogen) staining was performed prior to surface staining for Fig. 3–4. For cytokine detection in CD8 T cells, 5×105 naive splenocytes from CD8−/−mice was mixed with equal number of brain or splenic cells from infected mice and restimulation was similarly carried out for 16h in presence of toxoplasma lysate antigen (TLA, 30 μg/ml). 0.65 μl/ml of monensin (BD Biosciences) and 0.65 μl/ml of brefeldin A (BD Biosciences) were added during the final 9h of stimulation. Cytokine detection in splenic CD4 T cells was similarly carried out without CD8−/− splenocyte addition. After acquisition using BD FACS Aria or BD FACS Calibur or Cytek upgraded BD FACS Calibur, data was analyzed using Flowjo. Computation for enumerating polyfunctional cells was performed using PESTLE and SPICE programs, generously provided to us by Dr. Mario Roederer (NIH).

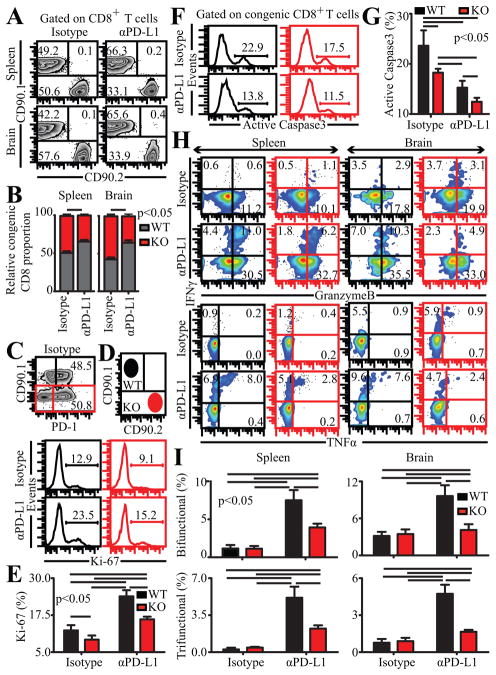

Figure 3.

CD40 plays a CD8 intrinsic role during rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells. Chronically infected mixed BM chimeras were treated with αPD-L1 for 2 weeks and analyzed at week 7 pi. A and B, Relative abundance of WT (CD90.1) and KO (CD90.2) CD8 T cells evaluated in spleen and brain by flow cytometry is presented as representative flow plots (A) or bar graphs (B). C, represents frequency of WT and KO splenic CD8 T cells in control chimeras expressing PD-1. D and E, The percentage of proliferating congenic splenic CD8 T cells was assessed by intracellular staining for Ki-67. Flow plots in red denote KO CD8 T cells throughout. Data is presented as histograms (D) or bar graphs (E). F and G, Histograms (F) and bar graphs (G) depict active caspase expressing CD8 T cells, evaluated after incubating splenocytes from chimeras at 37°C for 5h. H, IFNγ, Gzb and TNFα production by congenic CD8 T cells were evaluated in splenocytes or brain cells from infected mice in presence of TLA. I, represents the percentage of bifunctional (top panel) and trifunctional (bottom panel) CD8 T cells in spleen and brain. Results are representative of 2 experiments with at least 3 mice per group.

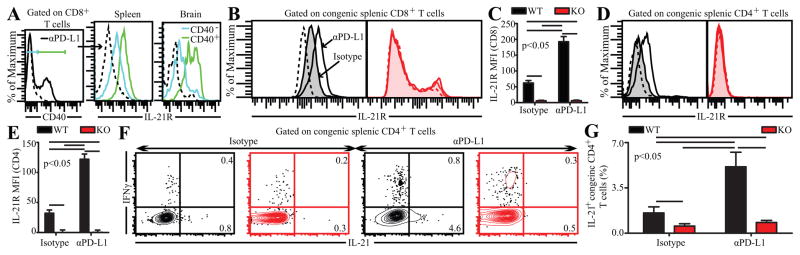

Figure 4.

CD40 plays a strictly T cell intrinsic role in mediating IL-21 and IL-21R expression on T cells. A, IL-21R expression was measured in CD40+ and CD40− splenic and brain CD8 T cells from αPD-L1 treated C57BL/6 mice. Congenic splenic CD8 (B and C) and CD4 (D and E) T cells in control and αPD-L1 treated BM chimeras were assessed for IL-21R expression. Data is presented as histograms (B and D) or bar graphs (C and E). F and G, Flow plots (F) and bar graphs (G) depict the percentage of IL-21 producing splenic CD4 T cells in these chimeras. The data represent 2 experiments with 3 mice per group.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise mentioned statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t test with P<0.05 taken as statistically significant. For comparing WT and KO T cell data from chimeras within the same treatment group, paired t test was used while for comparing WT or KO data between different treatment groups (i.e. isotype vs. αPD-L1) unpaired t test was utilized.

Results and Discussion

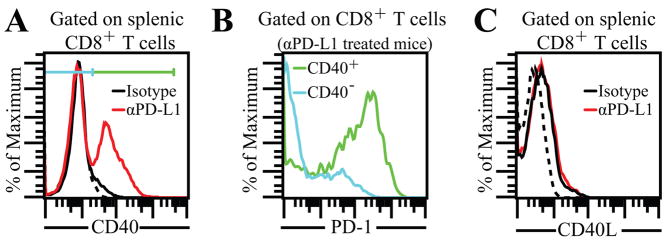

αPD-L1 treatment upregulates CD40 but not CD40L on CD8 T cells

To identify co-stimulatory molecules involved in the rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells, we examined a panel of these receptors on CD8 T cells in chronically infected mice treated with αPD-L1 or control antibody (data not shown). CD40 was identified as one of the co-stimulatory molecules showing high levels of differential expression. Minimal CD40 levels were noted on splenic CD8 T cells from control mice while high expression of this molecule occurred on CD8 T cells from αPD-L1 treated animals (Fig. 1A). Furthermore CD40 was preferentially expressed on PD-1+ subset (Fig. 1B) in αPD-L1 treated mice. Despite high CD40 expression on CD8 T cells from αPD-L1 treated mice, no differential expression of its receptor, CD40L was noted between CD8T cells from control and antibody treated animals (Fig. 1C). Combined, the above data points towards potential involvement of CD40-CD40L pathway during rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells.

Figure 1.

High expression of CD40 on CD8 T cells in αPD-L1 treated mice. A, Chronically infected mice were treated with αPD-L1 for 2 weeks and then sacrificed at week 7 pi. CD40 expression was analyzed on splenic CD8 T cells. Dotted line represents background fluorescence throughout. B, represents PD-1 expression on CD40+ and CD40− splenic CD8 T cells in αPD-L1 treated mice. C, Splenic CD8 T cells from control and αPD-L1 treated mice were evaluated for CD40L expression. The data represent 3 experiments with at least 4 mice per group.

CD40-CD40L signaling plays a critical role during rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells

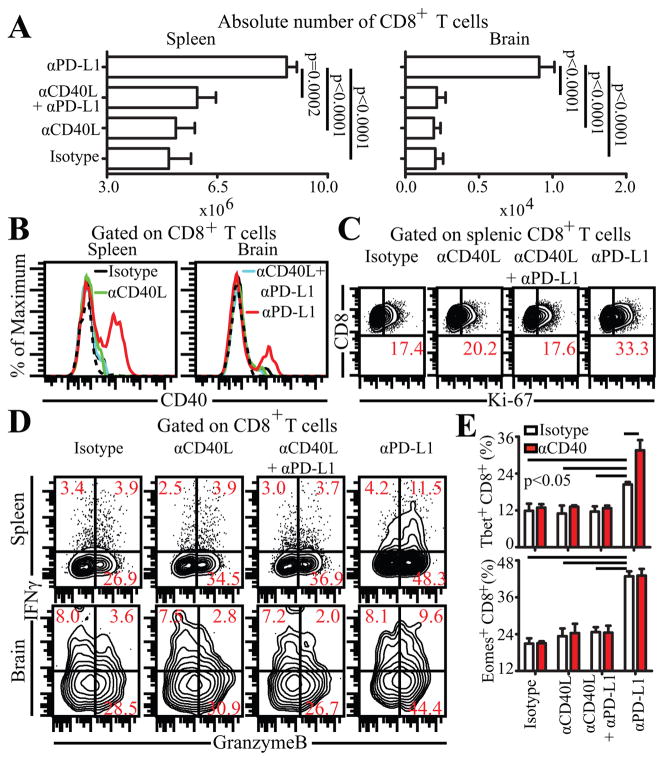

Since CD40 is differentially expressed on reinvigorated CD8 T cells, we next investigated if CD40-CD40L signaling played any role during the rescue process. To address this, chronically infected mice were administered control antibody or αPD-L1 or αCD40L or both (αPD-L1 and αCD40L) for 2 weeks (weeks 5–7) and then analyzed at week 7 pi. In agreement with observations by Reichmann et al, blockade of CD40-CD40L pathway alone had no profound effect on T cells-absolute number, CD40 expression, proliferation and functionality of CD8 T cells remained unaltered in both spleen and brain (Fig. 2 A,B,C and D) (7). While αPD-L1 treatment by itself was able to augment the above parameters (absolute number, CD40 expression, proliferation and effector functions), surprisingly, co-administration of αCD40L and αPD-L1 abrogated the rescue effect (Fig. 2 A,B,C and D) (2). This suggests that CD40-CD40L pathway plays a critical role during rescue of dysfunctional CD8 T cells. T-box family transcription factors, T-bet and Eomes, have been to shown to be important for proliferation, effector functions and survival of CD8 T cells (9). To further investigate the role of CD40 signaling on CD8 transcriptional control, purified splenic CD8 T cells from the above mice were treated in vitro with agonistic CD40 or control antibody. The expression of the above transcription factors was then evaluated by intracellular staining. In vivo co-administration of αPD-L1 and αCD40L abrogated increase in T-bet and Eomes expression and in vitro treatment with agonistic CD40 failed to augment these molecules (Fig. 2E). Surprisingly, agonistic CD40 treatment of CD8 T cells from αPD-L1 treated mice resulted in further increase in T-bet but not in Eomes (Fig. 2E). This suggests that while Eomes expression in CD8 T cells is independent of CD8 intrinsic CD40 signaling, T-bet expression is at least partially dependent on CD40 signaling directly on CD8 T cells.

Figure 2.

Blockade of CD40-CD40L pathway abrogates αPD-L1 mediated rescue of CD8 T cells. A, αPD-L1 or αCD40L or both were administered to chronically infected mice for 2 weeks and then sacrificed at week 7 pi. Absolute number of CD8 T cells was evaluated in spleen and brain. CD40 (B) and Ki-67 (C) expression was assessed in these mice by flow cytometry. D, IFNγ and Gzb production by CD8 T cells was evaluated in splenocytes or brain cells from infected mice in presence of TLA. E, Splenic CD8 T cells purified from in vivo antibody treated animals were evaluated for T-bet (top panel) and Eomes (bottom panel) after 6h in vitro stimulation with agonistic CD40 or control antibody. The data represent 2 experiments with at least 4 mice per group. Error bars represent standard deviation throughout.

CD8 intrinsic CD40 signaling is important for optimal rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells

The above data bears the implication that CD40 signaling directly on CD8 T cells is capable of modulating T-bet expression. However, it does not address if T cell intrinsic CD40-CD40L interaction in vivo can elicit a similar effect. Moreover, it does not rule out the possibility of CD40 expression on other cell types via changes in micro-environment such as cytokines or antigen burden, affecting CD8 T cells. To address the CD8 intrinsic role of CD40 during rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells in vivo, we generated bone marrow (BM) chimeras by injecting similar number of bone marrow cells from CD90.1(WT) and CD90.2+/+CD40−/− (KO) into lethally irradiated CD45.1 WT recipients. After reconstitution, the mixed bone BM chimeras were infected with T. gondii, treated with αPD-L1 for 2 weeks (weeks 5–7) and then analyzed at week 7 pi. In control antibody treated animals, WT and KO CD8 T cells were present in ~ 1:1 ratio and no difference in PD-1 expression was noted (Fig. 3A,B and C). However, after anti PD-L1 treatment this ratio was altered to 2:1 in both spleen and brain, suggesting that CD40 plays a CD8 intrinsic role in mediating their expansion during the rescue process (Fig. 3A,B). To further investigate if differential expansion of WT CD8 T cells in αPD-L1 treated chimeras was due to increased proliferation of these cells, we performed intracellular staining for Ki-67. As shown in Fig. 3D and E, irrespective of CD40 expression αPD-L1 treated chimeras showed greater CD8 T cell proliferation than controls. However, while CD40 deficiency minimally affected proliferation of CD8 T cells in control chimeras, it had a more pronounced effect in αPD-L1 treated chimeras. Next, we measured apoptosis, by examining active caspase3 expression. Regardless of CD40 deficiency, αPD-L1 treatment reduced CD8 apoptosis (Fig. 3F,G). Nevertheless, WT CD8 T cells were moderately more apoptotic than KO cells in both control and treated chimeras (Fig. 3F,G). Combined, this suggests that proliferation is the major mechanism responsible for preponderance of WT CD8 T cells in αPD-L1 treated chimeras. Next we examined if CD40 played a CD8 intrinsic role on effector functions of reinvigorated CD8 T cells. Irrespective of αPD-L1 treatment or CD40 deficiency, minimal IL-2 production was noted in CD8 T cells (data not shown). WT or KO CD8 T cells produced similar levels of IFNγ, Gzb and TNFα in control chimeras in both spleen and brain (Fig. 3H). While αPD-L1 treatment augmented these molecules in both WT and KO CD8 T cells, the latter exhibited far lower levels of Gzb and especially IFNγ and TNFα (Fig. 3H). Moreover, the percentage of both bifunctional and trifunctional CD8 T cells was highly depressed in KO CD8 T cells in treated animals (Fig. 3I). Finally we examined the transcriptional profile of CD8 T cells. Irrespective of CD40 deficiency similar levels of Eomes were noted in CD8 T cells in αPD-L1 treated chimeras (Supplemental Fig. 1). In contrast, αPD-L1 treatment augmented T-bet preferentially in WT CD8 T cells (Supplemental Fig. 1). Considering that Eomes has a critical role in mediating cytotoxicity, this may explain why KO CD8 T cells in αPD-L1 treated chimeras have unaffected single Gzb+ CD8 T cells but yet have attenuated IFNγ and TNFα production (9). Together, the data suggests that during rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells, CD40 plays a CD8 intrinsic role in mediating proliferation and effector functions of CD8 T cells. However unlike αCD40L treatment, CD40 deficiency on CD8 T cells in a CD40 sufficient environment does not entirely abrogate the ameliorative effects of αPD-L1, suggesting that that CD40 has an important CD8 extrinsic role as well.

CD40 plays an important role in mediating IL-21 and IL-21R expression

A previous study has demonstrated that CD40 stimulation upregulates IL-21R expression on chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells (10). Considering that IL-21-IL-21R pathway has been shown to be important for alleviating CD8 exhaustion in chronic viral models, we hypothesized that increased CD40 expression on CD8 T cells in αPD-L1 treated mice would result in upregulation of IL-21R on CD8 T cells (8). In agreement with our hypothesis CD40 expressing splenic and brain CD8 T cells in αPD-L1 treated WT animals, expressed higher IL-21R levels than CD40− population (Fig. 4A). To further examine, if augmented IL-21R expression was due to CD8 intrinsic CD40 signaling, splenic CD8 T cells were evaluated in antibody treated mixed BM (WT:KO) chimeras. As expected, αPD-L1 treatment substantially increased IL-21R levels only on WT CD8 T cells in the chimera (Fig. 4B,C). Irrespective of αPD-L1 treatment, minimal IL-21R expression was noted in KO CD8 T cells in both groups of chimera (Fig. 4B,C). Similar trends were also noted for CD4 T cells (Fig. 4D,E). This suggests that CD40 plays a strictly T cell intrinsic role in mediating IL-21R expression. Since IL-21 can also act in an autocrine fashion, we postulated that reduced IL-21R expression would lead to lower IL-21 production (11). As shown in Fig. 4F and G, WT CD4 T cells from αPD-L1 treated chimeras produced substantially more IL-21 than control chimeras. However, KO CD4 T cells irrespective of αPD-L1 treatment produced minimal IL-21. Examination T follicular helper (Tfh) cells (as defined by the following markers: CXCR5, PD-1 and Bcl-6), which are considered to be the major producers of IL-21, revealed similar trends (Supplementary Fig. 2) (12). Combined, this suggests that CD40 signaling plays a critical T cell intrinsic role in mediating IL-21-IL-21R signaling.

In summary, the current study for the first time highlights the critical role of positive signals from a co-stimulatory molecule in mediating rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells. Additionally, we show for the first time in an infectious disease model that CD40 plays an important CD8 intrinsic role in mediating CD8 T cell proliferation and poly-functionality, albeit in the context of reinvigoration of exhausted CD8 T cells. A recent study from our laboratory has demonstrated that αPD-L1 therapy preferentially rescues pre-existing PD-1 expressing CD8 T cells in chronically infected animals, suggesting that differential recruitment of naive T cells into antigen-specific pool plays at best a minor role during the rescue process (2). Based on this, it is tempting to speculate that CD40-CD40L pathway is especially important for this subset. However, further investigation is needed to definitively discriminate the effects of CD40-CD40L signaling on pre-existing CD8 T cells vs. new naive cells entering the antigen specific pool during chronic toxoplasmosis. Another important question that needs to be addressed in future studies is, how CD8 intrinsic CD40 signaling affects CD8 T cell function. While preliminary data suggests that T-bet may be involved in this process, it is likely that other transcription factors and cytokines such as IL-21 may be involved as well. Moreover the role of molecules directly involved in CD40 signal transduction such as TRAF6, which has been shown to be critical for memory CD8 development in the Listeria model, needs to be investigated in future studies of CD8 exhaustion (13). Another important and novel finding of the current report is the demonstration that CD40 plays a strictly T cell intrinsic role in mediating up-regulation of IL-21 and its receptor. As mentioned earlier, IL-21-IL21R signaling has been shown to play an important role in preventing CD8 exhaustion (8). In future studies, it will be important to discriminate between IL-21 dependent and independent role of CD8 intrinsic CD40 signaling during the rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells. The current findings complemented with a better understanding of the CD40-IL-21 axis in mediating dysfunctional CD8 T cell rescue will lead to more efficacious therapeutic vaccination strategies against tumors and chronic infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health grant AI-33325 to I.A.K.

Abbreviations used in this article

- WT

wild-type

- KO

CD40−/−

- pi

post infection

- TLA

toxoplasma lysate antigen

- PD-L1

PD ligand 1

- CD40L

CD40 ligand

- Gzb

GranzymeB

- BM

bone-marrow

- Tfh

T follicular helper cell

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Freeman GJ, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R, Sharpe AH. Reinvigorating exhausted HIV-specific T cells via PD-1-PD-1 ligand blockade. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2223–2227. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhadra R, Gigley JP, Weiss LM, Khan IA. Control of Toxoplasma reactivation by rescue of dysfunctional CD8+ T-cell response via PD-1-PDL-1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9196–9201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015298108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhadra R, Gigley JP, Khan IA. The CD8 T-cell road to immunotherapy of toxoplasmosis. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:789–801. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crawford A, Wherry EJ. The diversity of costimulatory and inhibitory receptor pathways and the regulation of antiviral T cell responses. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourgeois C, Rocha B, Tanchot C. A role for CD40 expression on CD8+ T cells in the generation of CD8+ T cell memory. Science. 2002;297:2060–2063. doi: 10.1126/science.1072615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee BO, Hartson L, Randall TD. CD40-deficient, influenza-specific CD8 memory T cells develop and function normally in a CD40-sufficient environment. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1759–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichmann G, Walker W, Villegas EN, Craig L, Cai G, Alexander J, Hunter CA. The CD40/CD40 ligand interaction is required for resistance to toxoplasmic encephalitis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1312–1318. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1312-1318.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yi JS, Du M, Zajac AJ. A vital role for interleukin-21 in the control of a chronic viral infection. Science. 2009;324:1572–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.1175194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Wherry EJ, Longworth SA, Northrup JT, Palanivel VR, Mullen AC, Gasink CR, Kaech SM, Miller JD, Gapin L, Ryan K, Russ AP, Lindsten T, Orange JS, Goldrath AW, Ahmed R, Reiner SL. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1236–1244. doi: 10.1038/ni1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Totero D, Meazza R, Zupo S, Cutrona G, Matis S, Colombo M, Balleari E, Pierri I, Fabbi M, Capaia M, Azzarone B, Gobbi M, Ferrarini M, Ferrini S. Interleukin-21 receptor (IL-21R) is up-regulated by CD40 triggering and mediates proapoptotic signals in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood. 2006;107:3708–3715. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nurieva R, Yang XO, Martinez G, Zhang Y, Panopoulos AD, Ma L, Schluns K, Tian Q, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Dong C. Essential autocrine regulation by IL-21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature. 2007;448:480–483. doi: 10.1038/nature05969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, Yang XO, Kang HS, Ma L, Wang YH, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Tian Q, Dong C. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pearce EL, Walsh MC, Cejas PJ, Harms GM, Shen H, Wang LS, Jones RG, Choi Y. Enhancing CD8 T-cell memory by modulating fatty acid metabolism. Nature. 2009;460:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.