Abstract

Vitamin D receptor (VDR) deficiency (knockout, KO) results in a failure of mice to generate an airway hyper-reactivity (AHR) response on both the Balb/c and C57BL/6 background. The cause of the failed AHR response is the defective population of iNKT cells in the VDR KO mice since wildtype (WT) iNKT cells rescued the AHR response. VDR KO mice had significantly fewer iNKT cells and normal numbers of T cells in the spleen compared to WT mice. In Balb/c VDR KO mice the reduced frequencies of iNKT cells was not apparent in the liver or thymus. VDR KO and WT Th2 cells produced similar levels of IFN-γ, and IL-5. On the Balb/c background Th2 cells from VDR KO mice produced less IL-13 while on the C57BL/6 background Th2 cells from VDR KO mice produced less IL-4. Conversely, VDR KO iNKT cells were defective for the production of multiple cytokines (Balb/c IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13; C57BL/6 IL-4, and IL-17). Despite relatively normal Th2 responses Balb/c and C57BL/6 VDR KO mice failed to develop AHR responses. The defect in iNKT cells as a result of the VDR KO was more important than the highly susceptible Th2 background of the Balb/c mice. Defective iNKT cell responses in the absence of the VDR result in the failure to generate AHR responses in the lung. The implication of these mechanistic findings for human asthma requires further investigation.

Introduction

Asthma is an immunologic disease characterized by airway inflammation, increased production of mucus and airway hyper-reactivity (AHR) (1). The symptoms of asthma include recurrent wheezing, coughing, and shortness of breath (1). There are different forms of asthma in the clinic including asthma associated with allergy, infection, air pollution and with exercise, which involves distinct pathways. The most common form of asthma is allergic asthma which is dependent on CD4+ T cells and associated with Th2-driven inflammatory responses in the lung (2). In experimental allergic asthma mice that are predisposed to Th2 responses (Balb/c) are more susceptible to disease than mice that are Th1 predisposed (C57BL/6). The mechanisms by which asthma is controlled are still not fully understood.

Invariant NKT (iNKT) cells have been shown to be required for the development of AHR by several groups (3). iNKT cells are a unique subset of lymphocytes which express markers of both αβTCR+ T cells and NK cells. iNKT cells express a conserved TCR, which recognizes glycolipid antigens. The sponge derived ligand α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) has been particularly useful in the characterization of iNKT cells because of the high specificity for CD1d and iNKT cells (3). iNKT cells act very early in an immune response and are responsible for the rapid production of large amounts of cytokines including IL-4, IL-13, and IFN-γ upon TCR stimulation (3). iNKT cell deficient mice (both CD1d−/− and Jα18−/−) fail to develop AHR and have greatly reduced eosinophilia after sensitization and challenge with allergen, ozone, or virus (4–6). The requirement of iNKT cells for AHR development was specific since adoptive transfer of WT iNKT cells into Jα18−/− mice reconstituted the development of AHR (4, 5). Activation of pulmonary iNKT cells can directly initiate the development of AHR as intranasal administration of αGalCer or glycolipids from Sphingomonas bacteria activated iNKT cells resulting in AHR and airway inflammation (7). The development of AHR in different models of asthma requires distinct subsets of iNKT cells. CD4+ iNKT cells produce both IL-13 and IL-4 and were required for allergen-induced AHR (4) while CD4− iNKT cell making IL-13 only and were involved in virus-induced AHR (4). iNKT cells participate in the development of AHR in the lungs and are therefore potential targets for regulation in asthma and allergy.

1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), the active form of vitamin D, is a potent regulator of immune responses. 1,25(OH)2D3 binds to the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which is a ligand inducible transcription factor. All cells of the immune system tested express the VDR and 1,25(OH)2D3 has been shown to be an important regulator of T cell function (8, 9). 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment has been shown to suppress animal models of Th1/Th17 type autoimmune diseases (10, 11). Furthermore, in vitro studies showed that 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment increased the production of IL-4 by Th2 cells and decreased the production of IFN-γ by Th1 cells (12, 13). Mice lacking the VDR have been shown to be more susceptible to autoimmunity and in particular inflammatory bowel disease (14). Th17 cells are targets of vitamin D since 1,25(OH)2D3 suppresses IL-17 production and T reg cells are induced by 1,25(OH)2D3 in vitro and in vivo (15). Two regulatory cells require the VDR for normal development and function the CD8αα+/TCRαβ+ T cells and iNKT cells (16, 17). C57BL/6 VDR KO mice failed to develop AHR following induction of experimental allergic asthma using ovalbumin (OVA) and Alum (18). The C57BL/6 VDR KO mice have very few iNKT cells (16). In order to determine whether a requirement of the VDR for Th2 and/or iNKT cells was responsible for the failure of C57BL/6 VDR KO mice to develop experimental asthma, experiments were done to evaluate the roles of these two cell types.

C57BL/6 VDR KO mice were backcrossed onto the Th2 biased and experimental allergic asthma susceptible Balb/c background. Consistent with the finding from the C57BL/6 VDR KO mice, Balb/c VDR KO mice failed to develop OVA induced experimental allergic asthma. AHR responses were low in VDR KO mice in the OVA model and also when αGalCer was administered intranasally to either the Balb/c or C57BL/6 VDR KO mice. In vitro, VDR KO and WT Th2 cell responses were very similar to each other while VDR KO iNKT cell responses were lower than WT for several different cytokines. The ability of iNKT cells to produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in response to αGalCer was 2–19 fold less in VDR KO than WT cells. iNKT cells from C57BL/6 WT mice produced high amounts of IL-17 and VDR deficiency reduced iNKT cell production of IL-17. The failure of VDR KO mice to develop AHR was due to impaired function of iNKT cells since adoptive transfer with WT iNKT cells reconstituted AHR development in VDR KO mice. The ability of VDR KO CD4+ T cells to become Th2 cells was largely intact. Conversely, VDR KO iNKT cells produced less of the asthma inducing cytokines compared to WT iNKT cells. The data demonstrate that the failure of VDR KO mice to develop AHR is not strain-specific and due to impaired iNKT cell function in the mice.

Materials and methods

Mice

The C57BL/6 VDR KO mice were backcrossed onto the Balb/c background (7 generations 99.2% Balb/c) at the University of Notre Dame (South Bend, IN) and the mice were a gift of Dr. Mary Ann McDowell. For experiments age- and sex-matched VDR KO and WT mice on C57BL/6 and Balb/c were produced at the Pennsylvania State University (University Park, PA). Experimental procedures received approval from the Office of Research Protection Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Pennsylvania State University.

Flow Cytometry

Single-cell suspensions of thymus, spleen and liver were isolated. Mononuclear cells from liver were prepared as described previously (17). Cells were stained with phycoerythrin (PE) labeled CD1d-PBS57 tetramers (PBS57 is a synthetic iNKT cell agonist, gift of the NIH Tetramer Facility, Atlanta, GA), CD4, CD8 and and PE-Cy5-labeled anti-TCRβ (H57-597) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Empty tetramers (NIH Tetramer Facility) and isotype control antibodies (BD Pharmingen) for each cell surface marker and cytochrome were used to establish specificity. For sorting, liver mononuclear cells were stained with PE labeled CD1d-PBS57 tetramer PE-Cy5-labeled anti-TCRβ. T cells (TCRβ+ tetramer−) and iNKT cells (TCRβ+ tetramer+) were then sorted by Cytopeia influx (BD, Seattle, WA). Purity of both T cells and iNKT cells was over 98%.

Cell culture and cytokine analysis

WT and VDRKO splenocytes were isolated and cultured in RPMI 1640. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 ug/ml streptomycin, and 5 mM 2-B-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For Th2 induction, 2 × 106 splenocytes were stimulated with of 5µg/ml of anti-CD3 (2C11) (BD Pharmingen) for 3 days in 6-well plates in the presence of IL-4 (5000 IU/ml, Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), and 1µg/ml anti-IFN-γ neutralizing antibodies(BD Pharmingen). Three ml of new media with 20 IU/ml of IL-2 (Peprotech) was added into each well at day 3. At day 4, cells were collected, washed twice, and re-stimulated with 10ng/ml of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and 2.5µg/ml of ionomycin for another 72 h (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) when the supernatants were collected (total of 7 days in culture). For iNKT cell cultures, 2×106 splenocytes were stimulated with 100nM of αGalCer for a total of 72h. Lungs were lavaged via the tracheal tube with 1 ml PBS at room temperature. Total leukocyte, lymph and basophile numbers were measured using a Coulter Counter (Coulter, Hialeah, FL). Cytokines in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were analyzed by ELISA using the standards and kits as provided (BD Pharmingen). Supernatants were analyzed for levels of IL-4, IL-5, IL-17, IL-13 and IFN-γ by a Luminex multiplex bead system kit (Lincoplex, Billerica, MA) on a Bioplex system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). For some experiments IFN-γ values were obtained by ELISA kits (BD Pharmingen).

OVA-induced allergic asthma model

Mice were immunized i.p. on d 0 and 5 with 50 µg/ml OVA (Sigma) complexed with aluminum hydroxide (10 µg OVA/1 mg Alum; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Beginning 12 days after immunization mice were exposed to 60 µg of OVA intranasally (i.n.) for 4 consecutive days, and sacrificed 24 h after the last exposure or on d15. For some experiments 2µg of αGalCer or PBS was administered to the mice at day 0. VDR KO mice also received purified iNKT cells (1.5 ×106) or T cells (1.5 ×106) i.p. from WT mice on day 0.

αGalCer induced lung inflammation

αGalCer (Axxora, San Diego, CA) was dissolved in PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20, heated to 80°C for 10 min, and sonicated for 5 min on ice. 2ug of αGalCer was administered i.n. to mice anesthetized with isofluorane. Glycolipid vehicles were administered as controls. 24 h after the αGalCer administration mice were analyzed for AHR and sections of the lungs were stained for lung inflammation.

AHR and lung histopathology

AHR was determined using a Flexivent mechanical ventilator (SciReq, Chandler, AZ). Mice were anesthetized and a cannula placed in the trachea so that the lungs were ventilated at a rate of 120 breaths/min, VT = 0.2 ml, flow rate 1.5 ml/s at 2–3 cm H2O PEEP. Airway pressure in response to methacholine (0–100 mg/ml) was determined using a differential pressure transducer. Following the AHR measurements lungs were fixed, sectioned (Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratories, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA) and scored for the severity of the inflammation using a range of 0 – no disease to 4 – maximal disease and exactly as previously described (18, 19).

Results

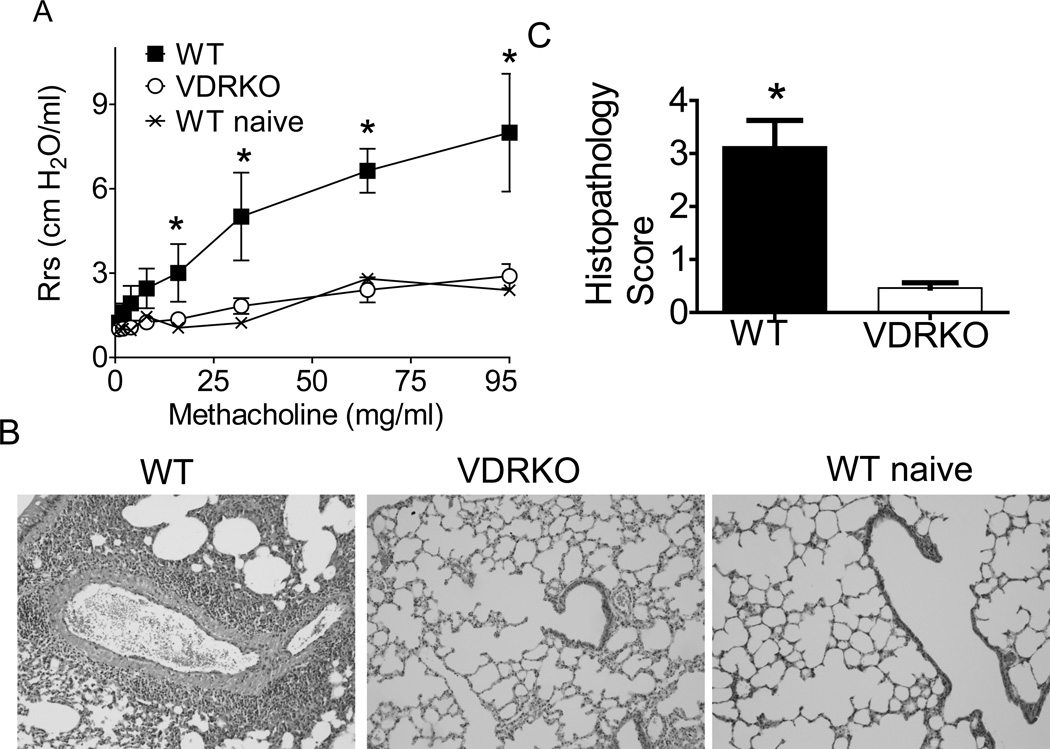

Balb/c VDRKO mice fail to develop experimental allergic asthma

VDR KO and WT mice on the Balb/c background were immunized with OVA and Alum to induce experimental allergic asthma exactly as described (18). Twenty four hours after the last i.n. challenge, mice were subjected to mechanical ventilation for analysis of AHR. As expected immunized WT Balb/c mice showed an increase in AHR with increasing dose of methacholine (Fig. 1A). Conversely immunized VDR KO mice did not respond to increasing doses of methacholine (Fig. 1A). In fact the AHR response of immunized VDR KO mice was the same as mock PBS treated WT mice (WT naïve, Fig. 1A). Histopathology sections from immunized WT mice showed increased leukocyte accumulation around the bronchi and bronchioles in the lungs (Fig. 1B). Immunized VDRKO mice had little inflammation, similar to what was found in the sections from naive WT mice (Fig. 1B). The lung histopathology scores from immunized VDRKO mice were significantly less than those from WT mice (Fig. 1C). The histopathology scores from primed WT mice were 3.2 ± 0.5 while primed VDRKO were 0.5 ± 0.1 (mean ± SEM). Balb/c VDRKO mice are resistant to the development of experimental allergic asthma induced by OVA/Alum immunization.

Figure 1. Balb/c VDR KO mice fail to develop experimental allergic asthma.

Balb/c WT and VDRKO mice were induced to develop allergic asthma. A) AHR was measured in naïve WT (WT + PBS) and OVA/Alum immunized and OVA challenged WT and VDR KO mice. Immunized WT mice developed AHR following increasing doses of methacholine. Conversely, immunized VDR KO mice failed to respond and the AHR response was similar to the WT + PBS naïve mice. n= 4 mice per group and one representative experiment of 4. The WT AHR response was significantly higher than VDRKO or WT + PBS, *P<0.05. B) The histopathology section from one representative lung from each group of mice in A is shown. C) The mean histopathology scores from all of the sensitized mice in the group. Values from VDR KO mice are significantly different than WT mice (n=12 mice per group, mean ± SEM, *P<0.05).

VDR KO mice are hyporesponsive to αGalCer

To determine the role of iNKT cells in the development of airway inflammation in VDRKO mice, αGalCer was administered i.n. to WT and VDRKO mice on the C57BL/6 and Balb/c backgrounds. As expected exposure to αGalCer 24h prior to methacholine challenge resulted in increased airway resistance in both C57BL/6 and Balb/c WT mice (Fig. 2A). Conversely, αGalCer treatment of VDR KO mice were nonresponsive to methacholine on both the C57BL/6 and Balb/c background (Fig 2A and Table 1). In fact, there was no increase in AHR responses with αGalCer treatment of VDR KO mice over that with the PBS controls. Airway resistance of WT mice was significantly higher than that of VDRKO or WT challenged with PBS at doses of methacoline over 25 mg/ml (Fig. 2A). Histopathology sections of the lungs showed that eosinophils and lymphocytes infiltrated into peribronchial spaces of the WT lungs exposed to αGalCer (Fig. 2B). The histopathology sections of VDR KO mice exposed to αGalCer were more similar to the unsensitized (PBS) mice than the αGalCer exposed WT (Fig. 2B, and WT PBS data not shown). The BALF from C57BL/6 WT mice exposed to αGalCer had high levels of IL-4 (Fig. 2C). Consistent with the lack of AHR response the C57BL/6 VDR KO mice exposed to αGalCer had no detectable IL-4 in the BALF and the IL-4 response was similar to the unsensitized PBS treated controls (Fig 2C). The data suggest that activation of pulmonary iNKT cells fails in the VDR KO mice regardless of the genetic background of the mice (Table 1).

Figure 2. αGalCer induced AHR fails in VDR KO mice on the Balb/c and C57BL/6 background.

WT and VDRKO mice were challenged i.n. with αGalCer and analyzed 24h later. A) αGalCer induced sensitivity to methacoline in Balb/c and C57BL/6 WT mice. αGalCer treatment of either Balb/c or C57BL/6 VDR KO mice failed to induce an increase in air resistance. WT αGalCer AHR values are significantly higher than all other groups, *P<0.05 (1 representative of 2 experiments, n=3 mice per group per experiment). B) The histopathology section from one representative lung from each group of mice in A is shown. C) BALF from WT and VDRKO mice on the C57BL/6 mice were collected to determine the IL-4 level. IL-4 was detectable only in the WT BALF from mice exposed to αGalCer. WT αGalCer IL-4 values were significantly higher than all other groups, *P<0.05 (n=6 mice per group, error bars are ± SEM).

Table 1.

VDR KO versus WT response on the Balb/c and C57BL/6 backgrounds1.

| Balb/c | IL-4 | IL-5 | IL-13 | IL-17 | IFN-γ | AHR | Lung Histo. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th22 | — | — | ↓ | — | — | ↓ | ↓ |

| iNKT3 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | — | — | ↓ | ↓ |

| C57BL/6 | IL-4 | IL-5 | IL-13 | IL-17 | IFN-γ | AHR | Lung Histo. |

| Th2 | ↓ | — | — | — | — | ↓ | ↓ |

| iNKT | ↓ | — | — | ↓ | — | ↓ | ↓ |

↑VDR KO response is significantly greater than WT, ↓VDR KO response is significantly less than WT, — VDR KO and WT responses are not different.

Th2: For cytokines indicates a summary of the results from Th2 cultures of the spleen (Fig. 4); for AHR and Lung Histopathology (Histo.) indicates a summary of the results from OVA/Alum induced experimental asthma.

iNKT: For cytokines indicates a summary of the results from iNKT cell cultures of the spleen (Fig. 4); for AHR and Lung Histo. indicates a summary of the results from αGalCer induced lung inflammation.

Balb/c VDRKO mice had reduced numbers of iNKT cells

Previously it’s been shown that the frequencies of CD4, and CD8 T cells in the spleen, liver and thymus of C57BL/6 VDR KO and WT are similar (17). The BALF from the lung of C57BL/6 VDR KO mice contained normal frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells compared to WT (Fig. 3C). The frequencies of CD4+ T cells were the same in VDR KO and WT Balb/c mice in the spleen while the Balb/c VDR KO BALF had significantly fewer CD8+ T cells compared to WT mice (Fig. 3B and 3D). CD4 frequencies are the same in the spleen and lung of Balb/c VDR KO and WT mice (Fig.3B and 3D). There were no differences in the numbers of lymphocytes collected from the spleens and BALF of VDR KO and WT mice and therefore the total CD4+ and CD8+ frequencies reflect the actual numbers of cells in the VDR KO and WT mice (Fig. 3 and (17)). The percentages of iNKT cells (defined as TCRβ and CD1d-PBS57 tetramer positive) were significantly lower in the Balb/c VDR KO spleen but not different in the BALF compared to Balb/c WT mice (Fig 3B and 3D). The frequencies of iNKT cells in the thymus and liver of Balb/c VDR KO mice were not significantly different from the Balb/c WT mice (Fig. 3B). This is in sharp contrast to the significant and 4–10 fold lower numbers of iNKT cells in the C57BL/6 VDR KO mice (17). In the spleen Balb/c and C57BL/6 KO mice had half as many iNKT cells as their respective WT counterparts (0.8–1% WT and 0.5-0.3% VDR KO). The BALF of both the Balb/c and C57BL/6 VDR KO lung contained similar frequencies and total numbers of iNKT cells compared to WT mice (Fig. 3C, 3D and 3E). The data show that VDR KO mice on the Balb/c background have reduced frequencies and numbers of iNKT cells but only in the spleen.

Figure 3. iNKT, CD4+ T, and CD8+ T cell numbers in the Balb/c VDR KO and WT mice.

A) The total number of iNKT, CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells isolated from the spleen of Balb/c mice. B) The frequency of iNKT cells (CD1d tetramer/TCRβ+ T cells) in Balb/c WT and VDR KO spleen, thymus and liver. VDR KO mice had significantly fewer iNKT cells than WT in the spleen (n=4–6 mice per group). The frequency of iNKT, CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells isolated from the BALF of C) C57BL/6 and D) Balb/c VDR KO and WT mice (n=6–7 mice per group). E) The total number of iNKT cells in the BALF of the C57BL/6 and Balb/c mice.

Th2 and iNKT cell responses in VDR KO mice

T cells are recruited to the lung during chronic asthmatic responses, producing cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 that are associated with the pathology of asthma and allergy (24–26). The underlying cause of the observed hyporesponsiveness of VDR KO mice to either OVA and Alum or αGalCer induced lung inflammation could be as a result of reduced Th2 cells or reduced iNKT cells or both. Splenocyte cultures were used to induce Th2 and/or iNKT cells in vitro and the profile of cytokine secretion evaluated. The Th2 cultures from VDR KO mice had comparable levels of IL-5, IL-17 and IFN-γ as the WT Th2 cell cultures (Fig. 4A and B). IL-13 was lower in the Th2 cell cultures from Balb/c VDR KO and IL-4 was lower in the C57BL/6 VDR KO Th2 cell cultures than WT. There was no effect on the Th2 cell production of IL-5, IL-17 and IFN-γ in VDR KO mice (Table 1).

Figure 4. Th2 and iNKT generated cytokine secretion from VDR KO and WT mice.

Splenocytes from WT and VDRKO mice were stimulated under Th2 or iNKT cell conditions and the ability to produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17 and IFN-γ were evaluated. Th2 cell cultures of A) Balb/c or B) C57BL/6 spleens. iNKT cells cultures generated by αGalCer treatment of C) Balb/c or D) C57BL/6 splenocytes. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of 3–4 individual mice and 1 representative of 3 experiments.

iNKT stimulation of splenocytes using αGalCer (72h) showed that VDR KO splenocytes secreted significantly less IL-4 than similarly treated WT cells (Fig 4C). Even though there are significantly fewer iNKT cells in the spleen of VDR KO mice IFN-γ secretion in response to αGalCer was not different between VDR KO and WT mice (Fig. 4C and D). IL-17 production by C57BL/6 VDR KO splenocytes was 51-fold lower than WT (Fig. 4D). VDR KO αGalCer stimulated splenocytes secreted 6–19-fold less IL-4, 4–8-fold less IL-5 and 2–3-fold less IL-13 (Fig. 4C and D). Only in the Balb/c VDR KO iNKT cell cultures did the IL-5 and IL-13 reduction reach significance (Fig. 4C and D). VDR deficiency has a significant effect on iNKT cell production of several key asthma inducing cytokines (Table 1).

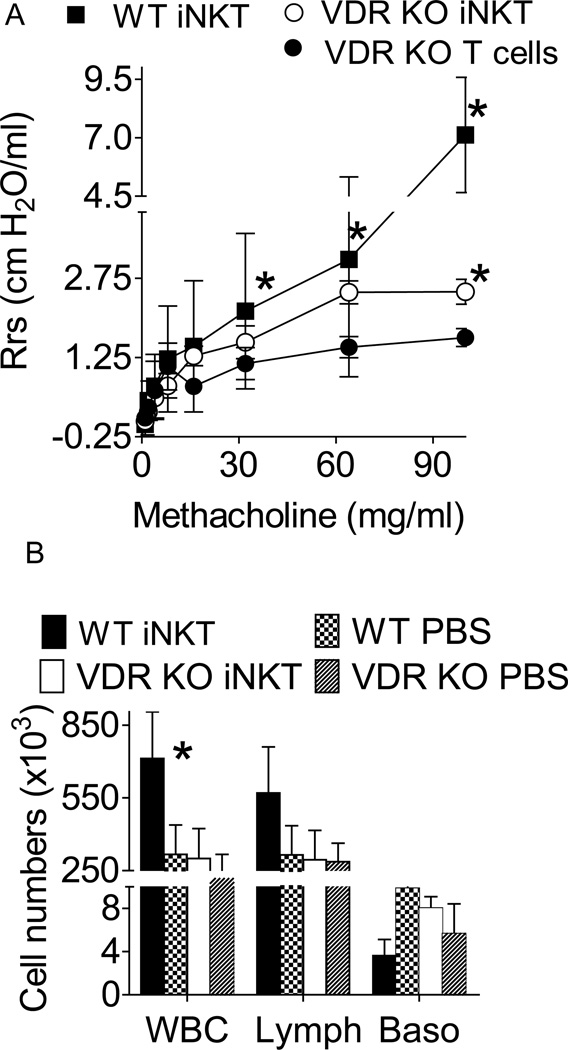

Transfer of WT iNKT cells to VDRKO mice rescues lung inflammation

iNKT cells or T cells were purified from WT mice and injected into VDRKO C57BL/6 recipients. Some of the mice were injected with αGalCer prior to being induced to develop experimental allergic asthma using OVA/Alum. AHR was highest in WT mice that had received αGalCer prior to OVA immunization (WT iNKT, Fig. 5A). AHR was lowest in VDR KO mice that received T cells plus αGalCer (VDR KO T cells, Fig. 5A). AHR responses of VDR KO mice that had received WT iNKT cells and αGalCer (VDR KO iNKT) approached those of the WT mice and were significantly higher than the VDR KO mice that received T cells at 95 mg/ml methacholine (Fig. 5A). The AHR of VDRKO mice with WT iNKT cells was not different from WT at 64 mg/ml methacholine (Fig 5A). The composition of BALF was analyzed following mechanic ventilation in the mice shown in Fig. 5A. Consistent with the elevated AHR measurements, WT mice with αGalCer and OVA immunization had more white blood cells (WBC) and lymphocytes (Lymph) than all other groups (Fig 5B). Eosinophils were not detected in either the VDR KO or WT BALF. The numbers of WBC were not different between VDRKO mice with WT iNKT cells, αGalCer and OVA immunization and WT mice with PBS and OVA immunization (Fig. 5B). The WBC counts in VDRKO with PBS and OVA immunization had slightly lower but not significantly lower WBC numbers than the WT PBS and VDR KO iNKT values (Fig 5B). WT transfer of iNKT cells rescues AHR development in VDR KO mice immunized with OVA/Alum.

Figure 5. WT iNKT cells rescued AHR in VDR KO mice.

Mice were injected with αGalCer and immunized/challenged with OVA. VDR KO mice were given WT iNKT cells (VDR KO iNKT) or WT T cells depleted of iNKT cells (VDR KO T cells). A) WT mice developed AHR following exposure to methacholine and the AHR response was significantly higher than VDR KO that received T cells mice (at doses of methacholine over 16 mg/ml, n= 5 mice per group). VDR KO mice that received iNKT cells had higher AHR responses than VDR KO mice that received T cells and the difference was significant at 95 mg/ml methacholine (n=5 mice per group), * P<0.05. B) Cellular influx in the BALF of WT and VDRKO mice 24 h after last OVA i.n. challenge. WT iNKT - αGalCer and OVA sensitized, WT PBS- PBS and OVA sensitized, VDR KO iNKT, αGalCer /iNKT cell transfer and OVA sensitized, VDR KO PBS- PBS and OVA sensitized. The value from WT αGalCer mice were significantly higher than all other groups (n= 5 mice per group, *P<0.05).

Discussion

The inability of VDR KO mice to develop AHR is a result of impaired iNKT cell development and not Th2 cell defects. Reconstitution of iNKT cells and not T cells was able to recover AHR responses in VDR KO mice. Interestingly, even in Th2 biased Balb/c mice; the iNKT cell defect overcomes the Th2 allergic asthma bias of the mice and VDR KO Balb/c mice fail to develop allergic asthma. The role of iNKT cells in experimental allergic airway disease has been demonstrated in several models. The production of IL-13, IL-4 and IL-5 by iNKT cells is thought to promote AHR, eosinophilia and IgE class switching (20, 21). In addition, iNKT cells that produce IL-17 result in the increased presence of neutrophils in the lungs (20, 21). Vitamin D has been shown to be important in the development of the neonatal lung (22). Data using bone marrow transplantation also suggests that in addition to the immune mediated effects of vitamin D in experimental asthma the lung may also require vitamin D (19). The data presented here supports a critical role for vitamin D in iNKT cell development and function in the lung. Previously it’s been shown that disease causing Th2 cells develop in the VDR KO host (19) and the data presented here support the finding that vitamin D is less critical for the regulation and development of Th2 cell responses. It is clear that iNKT cells can participate in asthma development and that vitamin D is an important iNKT cell regulator. The question that remains is whether iNKT cells and vitamin D participate in human disease.

Surprisingly Balb/c VDR KO mice had fewer iNKT cells but only in the spleen. This is in contrast to the result in C57BL/6 VDR KO mice that have fewer iNKT cells in all tissues examined but the lung (17). VDR expression is also needed for maturation of iNKT cells and VDR KO iNKT cells are defective for the production of cytokines (17). The data show that i.n. exposure to αGalCer failed to induce inflammation in the VDR KO lung regardless of the genetic background of the mice (Table 1). VDR expression is required for several aspects of iNKT cell development and function. The VDR mediated effects on iNKT cell frequency in the thymus and liver are different in Balb/c and C57BL/6 mice, while other functional aspects are similar including the inability to induce AHR and inflammation in the lung following αGalCer administration.

The effect of vitamin D on OVA induced experimental allergic asthma has been studied by several groups. The active form of vitamin D (1,25(OH)2D3) has been shown to have no effect, beneficial effects, and detrimental effects on various symptoms of experimental asthma (reviewed in (23)). 1,25(OH)2D3 has been shown to induce IL-4 and IL-13 secretion (24) and inhibit IL-4 secretion by Th2 cells in another study (25). This seemingly disparate result might reflect the population of cells present in the cultures. Beneficial effects of vitamin D might include the induction of T reg cells that have not only been shown to be induced but also to protect against experimental allergic asthma (26, 27). Other benefits of 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment might be the inhibition of IL-17 production (20, 21, 23). VDR KO mice have normal numbers of functional T reg cells (16). CD4+ T cells from VDR KO mice have more activated and memory cells that readily develop into Th17 and Th1 cells (14, 28). Th2 development is largely intact in the VDR KO mice (19). In the OVA/Alum models the critical T cell types for disease development include the T reg, Th2 cells and iNKT cells. In VDR KO mice the inability of the iNKT cells to induce a robust Th2 response with the presence of normal functional T reg cells prevents the induction of AHR and development of other symptoms of allergic asthma.

There has been extensive speculation that vitamin D deficiency may be associated with several chronic inflammatory diseases including asthma (23). These association studies lack the ability to understand the mechanisms by which a nutrient like vitamin D could impact chronic inflammatory diseases like asthma or inflammatory bowel disease. The epidemiological data in humans would seem to undermine the major conclusions from these more mechanistic studies in mice. One explanation for this is that vitamin D does not induce and regulate human iNKT cells. Another possibility is that iNKT cells are not important in the development of asthma in humans. For vitamin D and asthma the data from humans is not without controversy since there is at least one group that has shown that increased vitamin D supplementation during childhood is associated with increased wheezing (29). The role of iNKT cells in human asthma is also a controversial topic with different groups reporting disparate results and finding either very low frequencies (30) or high frequencies (60% of the T cells in the lung, (31)) of iNKT cells. There are numerous explanations for the discrepancies in the data and it seems possible that even low frequencies of iNKT cells could have a significant impact on asthma development. The connections between vitamin D status, iNKT cells and asthma in humans require further investigation.

Vitamin D is an important regulator of iNKT cells in the lung. In the absence of the VDR iNKT cells fail to induce Th2 cells and AHR in the lungs. Even in Balb/c mice that are very susceptible to experimental asthma the iNKT cell defect in VDR KO mice results in the failure to generate AHR. WT iNKT cells rescue AHR and asthma development when transferred to VDR KO mice. The iNKT cell data in isolation suggest that asthma might be made worse by increasing vitamin D status in humans. However, it is clear that vitamin D regulates several different pathways in the lung and therefore careful determinations of all mechanisms at play are required. A better understanding of the mechanisms by which vitamin D regulates both the lung and immune function is needed to be able to predict what effects increasing vitamin D status might have on human asthma. Several ongoing or planned human clinical trials are underway to look at the role of vitamin D in preventing and ameliorating asthma development so hopefully answers are forthcoming.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the National Institute of Health Tetramer Core Facility for the CD1d tetramers used in these experiments and the members of the Center for Molecular Immunology and Infectious Diseases for lively discussion.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and the Office of Dietary Supplements AT005378 and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke NS067563.

Nonstandard abbreviations

- AHR

airway hyperresponsiveness

- α-GalCer

α-galactosylceramide

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- i.n.

intranasal

- iNKT

invariant NKT

- KO

knockout

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

- WT

wildtype

References

- 1.Wills-Karp M. Immunologic basis of antigen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:255–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson DS, Hamid Q, Ying S, Tsicopoulos A, Barkans J, Bentley AM, Corrigan C, Durham SR, Kay AB. Predominant TH2-like bronchoalveolar T-lymphocyte population in atopic asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:298–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201303260504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akbari O, Stock P, Meyer E, Kronenberg M, Sidobre S, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Grusby MJ, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Essential role of NKT cells producing IL-4 and IL-13 in the development of allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity. Nat Med. 2003;9:582–588. doi: 10.1038/nm851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pichavant M, Goya S, Meyer EH, Johnston RA, Kim HY, Matangkasombut P, Zhu M, Iwakura Y, Savage PB, DeKruyff RH, Shore SA, Umetsu DT. Ozone exposure in a mouse model induces airway hyperreactivity that requires the presence of natural killer T cells and IL-17. J Exp Med. 2008;205:385–393. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim EY, Battaile JT, Patel AC, You Y, Agapov E, Grayson MH, Benoit LA, Byers DE, Alevy Y, Tucker J, Swanson S, Tidwell R, Tyner JW, Morton JD, Castro M, Polineni D, Patterson GA, Schwendener RA, Allard JD, Peltz G, Holtzman MJ. Persistent activation of an innate immune response translates respiratory viral infection into chronic lung disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:633–640. doi: 10.1038/nm1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer EH, Goya S, Akbari O, Berry GJ, Savage PB, Kronenberg M, Nakayama T, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Glycolipid activation of invariant T cell receptor+ NK T cells is sufficient to induce airway hyperreactivity independent of conventional CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2782–2787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510282103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhalla AK, Amento EP, Clemens TL, Holick MF, Krane SM. Specific high-affinity receptors for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: presence in monocytes and induction in T lymphocytes following activation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57:1308–1310. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-6-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Provvedini DM, Tsoukas CD, Deftos LJ, Manolagas SC. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors in human leukocytes. Science. 1983;221:1181–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.6310748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantorna MT, Hayes CE, DeLuca HF. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 reversibly blocks the progression of relapsing encephalomyelitis, a model of multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7861–7864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantorna MT, Hayes CE, DeLuca HF. 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol inhibits the progression of arthritis in murine models of human arthritis. J Nutr. 1998;128:68–72. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemire JM. Immunomodulatory role of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Cell Biochem. 1992;49:26–31. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240490106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahon BD, Wittke A, Weaver V, Cantorna MT. The targets of vitamin D depend on the differentiation and activation status of CD4 positive T cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:922–932. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Froicu M, Weaver V, Wynn TA, McDowell MA, Welsh JE, Cantorna MT. A crucial role for the vitamin D receptor in experimental inflammatory bowel diseases. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2386–2392. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Etten E, Mathieu C. Immunoregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: basic concepts. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu S, Bruce D, Froicu M, Weaver V, Cantorna MT. Failure of T cell homing, reduced CD4/CD8alphaalpha intraepithelial lymphocytes, and inflammation in the gut of vitamin D receptor KO mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20834–20839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808700106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu S, Cantorna MT. The vitamin D receptor is required for iNKT cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5207–5212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711558105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wittke A, Weaver V, Mahon BD, August A, Cantorna MT. Vitamin D receptor-deficient mice fail to develop experimental allergic asthma. J Immunol. 2004;173:3432–3436. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittke A, Chang A, Froicu M, Harandi OF, Weaver V, August A, Paulson RF, Cantorna MT. Vitamin D receptor expression by the lung micro-environment is required for maximal induction of lung inflammation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwamura C, Nakayama T. Role of NKT cells in allergic asthma. Curr Opin Immunol. 22:807–813. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lloyd CM, Hessel EM. Functions of T cells in asthma: more than just T(H)2 cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 10:838–848. doi: 10.1038/nri2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zosky GR, Berry LJ, Elliot JG, James AL, Gorman S, Hart PH. Vitamin D Deficiency Causes Deficits in Lung Function and Alters Lung Structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1596OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lange NE, Litonjua A, Hawrylowicz CM, Weiss S. Vitamin D, the immune system and asthma. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2009;5:693–702. doi: 10.1586/eci.09.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boonstra A, Barrat FJ, Crain C, Heath VL, Savelkoul HF, O'Garra A. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin d3 has a direct effect on naive CD4(+) T cells to enhance the development of Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:4974–4980. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Staeva-Vieira TP, Freedman LP. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits IFN-gamma and IL-4 levels during in vitro polarization of primary murine CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:1181–1189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorman S, Judge MA, Burchell JT, Turner DJ, Hart PH. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 enhances the ability of transferred CD4+ CD25+ cells to modulate T helper type 2-driven asthmatic responses. Immunology. 130:181–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taher YA, van Esch BC, Hofman GA, Henricks PA, van Oosterhout AJ. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 potentiates the beneficial effects of allergen immunotherapy in a mouse model of allergic asthma: role for IL-10 and TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2008;180:5211–5221. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruce D, Yu S, Ooi JH, Cantorna MT. Converging pathways lead to overproduction of IL-17 in the absence of vitamin D signaling. Int Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wjst M, Dold S. Genes, factor X, and allergens: what causes allergic diseases? Allergy. 1999;54:757–759. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vijayanand P, Seumois G, Pickard C, Powell RM, Angco G, Sammut D, Gadola SD, Friedmann PS, Djukanovic R. Invariant natural killer T cells in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1410–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akbari O, Faul JL, Hoyte EG, Berry GJ, Wahlstrom J, Kronenberg M, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. CD4+ invariant T-cell-receptor+ natural killer T cells in bronchial asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1117–1129. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]