Abstract

Unpredictable yet frequently occurring exception situations pervade clinical care. Handling them properly often requires aberrant actions temporarily departing from normal practice. In this study, the authors investigated several exception-handling procedures provided in an electronic health records system for facilitating clinical documentation, which the authors refer to as ‘data entry exit strategies.’ Through a longitudinal analysis of computer-recorded usage data, the authors found that (1) utilization of the exit strategies was not affected by postimplementation system maturity or patient visit volume, suggesting clinicians' needs to ‘exit’ unwanted situations are persistent; and (2) clinician type and gender are strong predictors of exit-strategy usage. Drilldown analyses further revealed that the exit strategies were judiciously used and enabled actions that would be otherwise difficult or impossible. However, many data entries recorded via them could have been ‘properly’ documented, yet were not, and a considerable proportion containing temporary or incomplete information was never subsequently amended. These findings may have significant implications for the design of safer and more user-friendly point-of-care information systems for healthcare.

Keywords: Electronic health records (E05.318.308.940.968.625.500), workflow (L01.906.893), documentation (L01.453.245), exit strategy, exception-handling, collaborative technologies, personal health records and self-care systems, developing/using clinical decision support (other than diagnostic) and guideline systems, systems supporting patient–provider interaction, human–computer interaction and human-centered computing, improving healthcare workflow and process efficiency, system implementation and management issues, social/organizational study, qualitative/ethnographic field study, cognitive study (including experiments emphasizing verbal protocol analysis and usability), methods for integration of information from disparate sources, information storage and retrieval (text and images), data exchange, communication and integration across care settings (inter- and intraenterprise), visualization of data and knowledge, developing/using computerized provider order entry, diamond

Introduction

A medical facility is a complex, oftentimes turbulent environment full of unpredictable yet frequently occurring situations that require contingent actions deviating from normal practice, referred to as ‘anticipated exceptions’ in this paper. Failing to accommodate such anticipated exceptions in the design of a health information technology (HIT) system can introduce severe disruptions to clinical work.1–5 For example, Han et al reported that not allowing medication orders to be placed prior to patient arrival, even for critically ill patients, was among the reasons for a suspected mortality increase following the implementation of a computerized prescriber order entry system.2 3 Recent studies have also shown that many HIT-associated unintended consequences were attributable to simplistic, linear designs that hampered HIT systems' capability to manage complex exception situations.6 7

‘Exit strategy’ is a term commonly used in the military to describe tactics for escaping from unfavorable situations. In this paper, we borrow it to describe software features deliberately built into HIT systems, electronic health records (EHRs) in particular, to handle anticipated exceptions. Our investigation was focused on a special class of EHR exit strategies: methods used to help clinicians temporarily address limitations imposed by structured data entry, which may prevent them from documenting, for example, certain patient care data that could not be easily classified or codified using a given taxonomy or nomenclature. While such exit strategies can be useful aids to reduce disruptions/delays and to prevent misinterpretation of the data in future patient care episodes or in research, they could also be misused as a speedy way of entering all types of patient care data—some of which perhaps could have been properly classified or codified with additional effort. Optimal approaches to providing such exit strategies, however, are unknown.

Through analyzing how end users utilized several exit strategies implemented in an ambulatory EHR system, we conducted an empirical examination of this intricate, double-edged nature of providing software-embedded exception-handling procedures. In this case report, we present the results of our evaluation of factors of use and clinical appropriateness of EHR exit strategies for structured documentation of clinical problems, medications, and observations.

Materials and methods

Setting

The empirical study was conducted in an ambulatory primary care practice at the Western Pennsylvania Hospital (WPH), a large urban teaching hospital located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. The EHR system, jointly developed by WPH practitioners and the research team (KZ, RP, MPJ, HSD), was designed to help the practice manage its daily operations and provide clinicians with electronic documentation and computerized decision-support capabilities.

The system was deployed in the study practice in June 2005. The research data collection began 3 months later and lasted 12 months. During this period, 34 residents, 10 attending physicians, and 10 nurses and physician assistants (PA) used the system in their day-to-day patient care activities.

Types of exit strategies

The EHR system incorporated several exit strategies to accommodate a variety of clinical purposes. In this paper, we focus on the exit strategies specifically designed to assist in clinicians' structured documentation of clinical data, collectively referred to as ‘data entry exit strategies.’

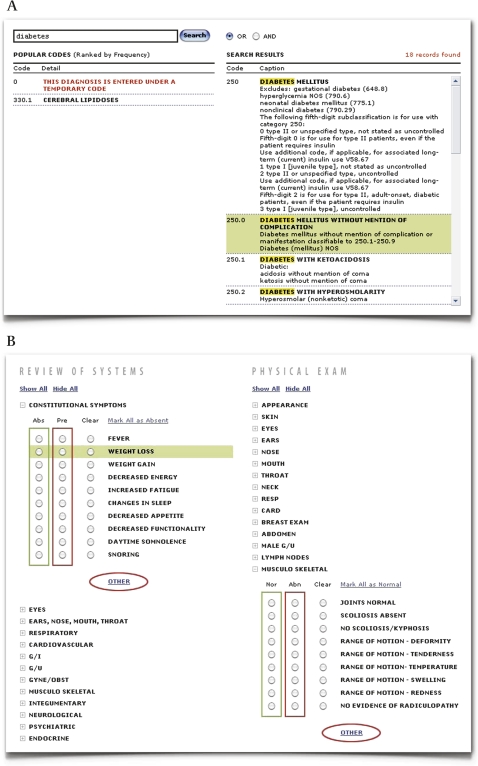

Structured data entry requiring controlled medical vocabularies is used in two main documentation areas of the EHR system: (1) ‘Current Problem List and Past Medical History’ based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Volume 1 and 2, referred to as ‘Problems’ hereafter; and (2) ‘Active Medications and Medication History’ (‘Medications’) based on FDA's National Drug Code Directory (NDC). Because documenting clinical data in a structured format is a very challenging task for frontline clinicians,8–10 we implemented several features to facilitate structured data entry, such as a full-text vocabulary search function and a dynamic list of most frequently used codes in the past 30 days. The provision of these features, however, does not warrant full elimination of exception situations wherein clinicians may still fail to find an appropriate code, or may not be able to locate one in a timely manner. To help clinicians escape from such situations, we introduced an exit strategy that permits temporary documentation of problems/diagnoses or medication prescriptions under a ‘Zero Code’ (figure 1A). Data entered using this placeholder code are clearly flagged in a distinctive color and font in the EHR's user interface, and can be easily revisited and updated.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the data entry exit strategies. (A) ‘Zero Code’ exit strategy provided on the ‘Problems’ form. (B) ‘RSPE-Other’ exit strategy provided on the ‘Review of Systems’ and ‘Physical Exam’ (RSPE) forms.

In the EHR system, clinical observations and physical examination results are documented using itemized templates provided on the ‘Review of Systems’ form and the ‘Physical Exam’ form, together referred to as ‘RSPE’ forms. These itemized templates (provided in appendix 1) were developed by the attending physicians in the study practice to encompass what they collectively considered to be most common and most essential RSPE data elements for capture in a structured format. Although documenting RSPE findings using the itemized templates is strongly preferred, categories labeled as ‘Other’ were made available on both forms in case the predefined classification schema might not be able to accommodate all types of RSPE data (figure 1B). In this paper, we refer to this exit strategy as ‘RSPE-Other.’

Evaluation methods

To examine whether the usage of the exit strategies may be associated with environmental variables or clinician characteristics, we performed a longitudinal analysis to relate their utilization rates to: (1) number of months elapsed since the EHR system's initial deployment (a surrogate measure of ‘postimplementation system maturity’), (2) monthly patient visit volume of the study practice (a surrogate measure of its activity levels), (3) clinician type, and (4) gender (the study sample consisted of 14 female residents, five female attending physicians, and nine female nurse and PA users, out of a total number of 34, 10, and 10, respectively). We also incorporated in the model the total number of operations in which an exit strategy could be used by a clinician to represent the clinician's level of ‘germane’ clinical activities (‘opportunities to use’). In the longitudinal analysis, a generalized estimating equation (GEE) with logistic link was employed to account for correlations between the observations obtained from the same users.11

Following the statistical analysis, we conducted an expert review to determine whether the clinical data entered using the exit strategies could have been documented via standard, recommended practice, that is, whether the clinicians' decision to ‘exit’ could be clinically justified. Two practicing physicians (DAH, pediatrics; AAH, internal medicine) reviewed the data independently. First, they dichotomized each of these data entries as ‘judged appropriate’ versus ‘judged inappropriate.’ Then, through consensus development, they created a thematic structure of common types of exit strategy uses either as indicated by the clinicians in their narrative annotation, or as inferred by the two reviewers. Note that prior to the expert review, we used a computer program to flag the ‘Zero Code’ data not accompanied by any supplemental narratives as ‘flagged inappropriate.’ Such data were unlikely to be clinically meaningful and therefore were not reviewed by the expert reviewers.

Results

During the 12-month study period, the exit strategies were used to document 112 of 1622 (6.9%) problems and diagnoses, 243 of 2281 (10.7%) medication prescriptions, and 180 of 4385 (4.1%) RSPE annotations. A breakdown of the utilization rates by clinician type is provided in appendix 2.

The results of the longitudinal analysis, reported in table 1, show that the exit strategy utilization rates are not associated with postimplementation system maturity or a higher volume of patient visits. Residents, as compared to attending physicians, were more likely to resort to the ‘Zero Code’ strategy when documenting ‘Problems’ (95% CI (1.03 to 4.29), p<0.05), and gender is a significant predictor of the usage of ‘Zero Code’ provided on the ‘Medications’ form: male users tended to utilize this exit strategy nearly five times more often than females (95% CI (1.94 to 11.5), p<0.001). Further, the total number of germane clinical activities (‘opportunities to use’) did not significantly affect the utilization rates of each exit strategy.

Table 1.

Longitudinal analysis results based on the generalized estimating equation (GEE) model

| Independent variables | Dependent variable (monthly utilization rates) | |||||

| ‘Zero code—problems’ | ‘Zero code—medications’ | ‘RSPE-other’ | ||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Postimp. system maturity | 1.15 | (0.96 to 1.40) | 1.00 | (0.85 to 1.14) | 1.00 | (0.81 to 1.13) |

| Monthly visit volume | 1.00 | (1.00 to 1.01) | 1.00 | (0.99 to 1.01) | 1.00 | (0.99 to 1.00) |

| Residents | 2.10* | (1.03 to 4.29) | 0.94 | (0.56 to 1.60) | 1.36 | (0.77 to 2.42) |

| Attending physicians | – | † | 0.89 | (0.56 to 1.42)] | – | † |

| Nurses and PAs | – | ‡ | – | † | Not applicable§ | |

| Male | 1.32 | (0.77 to 2.27) | 4.72** | (1.94 to 11.5) | 1.52 | (0.70 to 3.30) |

| Opportunities to use | 0.99 | (0.98 to 1.01) | 1.00 | (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 | (0.99 to 1.00) |

*p<0.05, **p<0.001.

Reference group.

No usage recorded.

The nurse and PA users' clinical responsibilities did not involve documentation of the ‘Review of Systems’ and ‘Physical Exam’ (RSPE) findings.

The expert review results are shown in table 2. Seventeen problems and diagnoses (15.2%) and 69 medication prescriptions (28.4%) were flagged as inappropriate by the computer program. With a converging consensus (Cohen's kappa: ‘Problems’ 1.0; ‘Medications’ 0.95; ‘RSPE-Other’ 1.0), the two reviewers deemed a majority of the remaining data entered under ‘Zero Code’ inappropriate: they could have been properly coded yet were not, or were entered into a wrong EHR section where they did not belong (eg, certain ‘Problems’ data entries should be documented under ‘Social History’ instead). Among the ‘Problems’ entered under ‘Zero Code’, 14 were labeled as ‘unable to judge.’ Most of them sought to record uncertain findings at the point of documentation: the reviewers could not determine whether using exit strategies to document such data should be considered appropriate given the lack of knowledge regarding how to properly document clinical uncertainty in EHRs. Finally, both reviewers deemed a majority of the ‘RSPE-Other’ usage appropriate since such data could not be comfortably entered using the itemized templates.

Table 2.

Expert review results

| Flagged inappropriate | Judged appropriate | Judged inappropriate | Unable to judge | ||

| Valid problems or diagnoses that could have been coded | Not germane to ‘problems’ | ||||

| Procedures | Other | ||||

| 2A. ‘Problems’ (n=112) | |||||

| 17 (15.2%) | 0 | 61 (54.5%) | 2 (1.8%) | 18 (16.1%) | 14 (12.5%) |

| – | – | ‘posttraumatic stress—attacked by pitbulls 2004’, ‘Parkinson's disease’ | ‘s/p roux en y gastric bypass’, ‘splenectomy’ | ‘Driver's Physical—Approved’, ‘Colon cancer screening’ | ‘2 Small ulcers?? on the uvula’, ‘disc exam limited’ |

| Flagged inappropriate | Judged appropriate | Judged inappropriate | Unable to judge | |||

| Valid medication prescriptions that could have been coded | Not germane to ‘medications’ | |||||

| Vitamin or supplements | Aspirin | Other | ||||

| 2B. ‘Medications’ (n=243) | ||||||

| 69 (28.4%) | 21 (8.6%) | 60 (24.7%) | 28 (11.5%) | 65 (26.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| – | ‘Flax seed oil capsule’, ‘sleeping pill’ | ‘Oscal D 1250 mg’, ‘multivitamin’ | ‘ASA 81MG QD’, ‘aspirin 81 mg qd’ | ‘CELEXA 40MG’, ‘Tylenol 325 mg’ | – | – |

| Flagged inappropriate | Judged appropriate | Judged inappropriate | Unable to judge | |

| Miscategorized* | Not germane to RSPE | |||

| 2C. ‘RSPE’ annotations (n=180) | ||||

| – | 166 (92.2%) | 3 (1.7%) | 11 (6.1%) | 0 |

| ‘bruising on arms’, ‘pedal edema’ | – | ‘see hpi’, ‘previous hysterectomy approximately 7 years ago’ | – | |

‘Review of Systems’ data mistakenly entered into the ‘Physical Exam’ section, or vice versa.

RSPE, ‘Review of Systems’ and ‘Physical Exam.’

Discussion

Incorporating exception-handling capabilities into EHRs, and HIT systems in general, may provide a potential means to streamline clinical work by temporarily suppressing disruptions and thus avoiding delays. However, such capabilities may be misused or exploited as a way to intentionally circumvent recommend practice. Through analyzing clinician utilization of several documentation-related exit strategies implemented in an ambulatory EHR system, this study aimed to empirically evaluate this double-edged nature of providing software-embedded procedures for handling exception situations.

Usage patterns

The overall exit strategy utilization rates were low during the study period, indicating that the provision of these exception-handling procedures did not engender clinicians' over-reliance on them as a speedy way of entering data. Further, the two expert reviewers deemed a majority of the RSPE-Other annotations appropriate. This result suggests that clinicians' work, and likely their thought process while examining patients and documenting clinical findings, could have been interrupted if this exit strategy were not available.

On the contrary, the two reviewers found most of the problems, diagnoses, and medications entered under ‘Zero Code’ could not be clinically justified, indicating that the clinician users either lacked a good understanding of the nature of medical coding or had difficulties in using the controlled medical vocabularies provided. This situation may become exacerbated as the healthcare system in the USA migrates to more complex coding systems such as ICD-10-CM and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT), and the coding responsibilities increasingly shift from professional coders to frontline clinicians.

The longitudinal analysis of exit strategy usage did not reveal any declining trends over time, suggesting that the learning and adaptation effect was not an influential factor, or its influences might have already been diminished when the data collection of this study began 3 months after the EHR system went live. Similarly, the monthly patient visit volume of the study practice did not have a significant impact on exit strategy usage; nor did the amount of germane clinical activities by individual users. These findings suggest that clinicians' needs to exit unwanted situation might be persistent regardless of environmental influences.

Additionally, different types of clinicians demonstrated distinct usage patterns. Residents were more likely to resort to the ‘Zero Code—Problems’ strategy than attending physicians, and male users utilized ‘Zero Code—Medications’ much more often than females. These findings suggest that EHR training strategies should be tailored based on the characteristics of users, in anticipation that certain behaviors might be particularly prominent among certain user groups. Further, it may be also possible to use adaptive designs in EHR systems to cater to unique needs and preferences of clinicians with distinct backgrounds, such as different levels of medical training.

Reasons for resorting to the data entry exit strategies

The tension between structured and narrative documentation has been well recognized.10 The data-entry exit strategies described in this paper may provide a solution to mitigating this tension by facilitating the capture of structured data while preserving certain information elements that cannot be adequately accommodated by structured forms. For example, in several instances, ‘Zero Code’ was used to document pertinent negatives (action performed while no findings resulted), for example, ‘(the patient is) on no meds at this time.’ On a paper form, clinicians can add an annotation in any convenient spot to indicate pertinent negatives, while on a computerized structured data entry form, making such a note can be rather difficult unless the function is explicitly provided.

Further, a significant number of ‘Zero Codes’ entered through the ‘Problems’ form were used to express clinical uncertainty at the point of documentation—for example:

‘Submandibular space infection-Lymphadenitis vs Ludwig's angina (unlikely). Would treat with Abx. Ctu peroxide mouth rinse. F/U with Oral surgeon’

‘Diarrhea—seems to be of acute nature will check cbc and bmp and lft’

‘Questionable hx of Crohns’

Attempting to interpret the clinicians' rationale behind these narrative annotations raised a number of interesting questions pertaining to EHR design: (1) Should such data, of a clearly work-in-progress nature, be entered into EHRs which would then become part of the patient's legal medical record? (2) Should such data be recorded in the ‘Current Problem List and Past Medical History’ section or in another, perhaps more appropriate ‘Transitory Information’ section? (3) Should a deterministic, billable code be mandated, even if the clinical findings are not yet certain at the point of data entry? (4) Would a probabilistic scale allowing indication of the degree of uncertainty increase the value of codified data, and if so, how should it be implemented.?

Seeking answers to these questions is beyond the scope of this case report. However, the fact that the clinicians repeatedly resorted to exit strategies to enter such data suggests that structured data-entry forms might not adequately support their documentation needs and, perhaps more importantly, their mental model of clinical reasoning.

Lessons learned

Despite the demonstrated value of providing exit strategies through EHRs, our analysis did highlight several issues of concern. Although exit strategies enabled actions that would be otherwise difficult or impossible, many data entries recorded via these exception-handling procedures could have been ‘properly’ documented according to recommended practice, yet were not, and a significant proportion containing temporary or incomplete information were never subsequently amended.

That the utilization rates of the data-entry exit strategies were associated neither with postimplementation system maturity nor with patient visit volume, suggests the clinicians' tendency to resort to exit strategies might have become part of their work routine. Hence, the exit strategies provided in the EHR system—legitimate ‘workaround’ solutions to a degree—could be responsible for diminishing the clinicians' motivation to adhere to recommended practices. Close monitoring of such potential unintended consequences is therefore needed. When exit strategies must be provided to allow for the handling of extreme situations, mechanisms should be in place to ensure that the residuals as a result of aberrant actions, such as placeholder data entered to temporarily accelerate clinical work, will be promptly rectified.

Study limitations

The findings of this empirical research should be interpreted within the boundary of its limitations. First, the idiosyncrasies of the EHR system, as well as those of the study clinic, might give rise to unique exit strategy utilization behaviors not generalizable to other settings. Second, in this investigation, we only used computer-recorded data to infer reasons underlying the exit strategy usage, which limited our ability to understand the root causes of the exception situations that clinicians had to cope with. Future work is needed to study and address the sources of such exception situations, so that the need to handle them can be minimized.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Western Pennsylvania Hospital where the empirical study was conducted, and all participating clinicians whose enthusiasm and patience made this research possible.

Appendix 1. Itemized templates of the ‘review of systems’ and ‘physical exam’ forms

1. Review of systems

-

Constitutional symptoms

Fever

Weight loss

Weight gain

Decreased energy

Increased fatigue

Changes in sleep

Decreased appetite

Decreased functionality

Daytime somnolence

Snoring

Other

-

Eyes

Decreased vision

Pain

Red

Double vision

Discharge/watering

Other

-

Ears, nose, mouth, throat

Discharge

Hearing loss

Dysphagia

Ulcers

Sore throat

Earache

Facial pain

Nasal block

Other

-

Respiratory

Dry cough

Dyspnea

Hemoptysis

Wheezing

Productive cough

Last CXR

PPD

Hoarseness

Other

-

Cardiovascular

DOE

Chest pain

Palpitations

Peripheral edema

PND

Orthopnea

Other

-

G/I

Nausea/vomiting

Early satiety

Reflux

Odynophagia

Abdominal pain

Hematemesis

Change in bowel habits

Melena

Hematochezia

Other

-

G/U

Dysuria

Increased frequency

Decreased flow

Hematuria

History of UTI

Urgency

Poor stream

Discharge

Incontinence

Other

-

GYNE/OBST

Menstrual periods

Perimenstrual problems

h/o PID

Other

-

Musculo skeletal

Muscle weakness

Cramping

Muscle pain

Morning stiffness

Other

-

Integumentary

Mole changes

Rash

Sun damage

Hx of skin cancer

Joint pain

Other

-

Neurological

Headache

Weakness

Paresthesias

Seizures

Headtrauma

Hx CVA

Abnormal speech

Abnormal gait and coordination

Neuropathic pain

Altered mental status

Radiculopathy

Forgetfulness

Other

-

Psychiatric

Mood

Anxiety

Sleep

Sleep

Suicidal ideation

Psychiatric disorders

Other

-

Endocrine

Fatigue

Polyuria

Polydipsia

Polyphagia

Thyroid disease

Other

-

Back

Pain

Injury

Other

-

Breast

Mass

Discharge

Skin changes

Other

-

Hematologic

Hx anemia

Easy bruising

Hx blood transfusion

Other

-

Allergic/immunologic

Rhinitis

Wheezing

Hives

Pruritus

Watery eyes

Other

2. Physical exam

-

Appearance

Appearance of patient

Alert and oriented

No distress

Other

-

Skin

No rashes, lesions or ulcers, no discoloration

Warm and dry, normal turgor

Other

-

Eyes

Sclera white

Conjunctivae clear

EOMI

Lids without lag

PERRLA

Discs flat

No hemorrhages or exudates

Other

-

Ears

Tympanic membranes translucent

Canal walls without discharge

Hearing non-impaired

No TM perforation

No TM bulge

Other

-

Nose

Mucosa and turbinates pink

Septum midline

Other

-

Mouth

Lips pink and symmetrical

Gums healthy

Oral mucosa without lesions

Normal dentition

Dental hygiene

Other

-

Throat

Tongue without lesions

No erythema/congestion

Normal tonsils

No PND

Other

-

Neck

Full ROM, trachea midline

No thyromegaly

No lymphadenopathy

No bruits

Other

-

Resp

Normal respiration rate, unlabored

Lung fields

Sounds

Wheeze

Crackles

Other

-

Card

No lifts, heaves, or thrills

S1 and S2 normal

RRR

No JVD

Normal pedal pulse

No murmurs, gallops, clicks

Other

-

Breast exam

Breasts symmetrical

No lumps, masses, discharge or tenderness

Other

-

Abdomen

No bruits

Normoactive bowel sounds

No masses or tenderness

No hepatosplenomegaly

No hernias

Rectal, normal tone, no hemorrhoids or masses

Rectal refused

No guarding/rebound/tenderness

Other

-

Male G/U

Scrotum, testes, without tenderness, swelling or masses

No penile discharge, lesions

Prostate normal

Other

-

Female G/U

No external masses, lesions, scars, rashes, or swelling of vulva

Labia, clitoris, vaginal orifice, and urethral meatus intact without discharge

Bladder, non-bulging, non-tender

Cervix pink without lesions, odor, or discharge

Uterus midline, non-tender, firm and smooth

No adnexal masses or tenderness

Other

-

Lymph nodes

No neck lymphadenopathy

No axillary lymphadenopathy

No groin lymphadenopathy

Other

-

Musculo skeletal

Joints normal

No scoliosis/kyphosis

Range of motion—deformity

Range of motion—tenderness

Range of motion—temperature

Range of motion—swelling

Range of motion—redness

No evidence of radiculopathy

Other

-

Extremities

No clubbing, cyanosis

No muscle atrophy or weakness

No calf tenderness

No edema

Normal Peripheral pulses

No ulcers

No chronic venous stasis

Other

-

Neurologic

Cranial nerves intact

Normal deep tendon reflexes

Superficial touch and pain sensation intact bilaterally

Normal muscle strength

Normal muscle tone

Babinski absent

Gait coordinated and smooth

Cerebellar functions normal

Normal memory

Other

-

Psychiatric

Normal judgment and insight

Alert and oriented × 3

Recent and remote memory intact

No mood disorders noted, appropriate affect

Other

Appendix 2. Utilization rates of the data-entry exit strategies by clinician type

| Measure | Clinician type | |||||

| Residents (n=34) | Attending physicians (n=10) | Nurses and PAs (n=10) | ||||

| n | %* | n | %* | n | %* | |

| Total no of problems and diagnoses | 998 | 61.5 | 559 | 34.5 | 65 | 4.0 |

| Entered under ‘Zero Code’ | 79 | 7.9 | 33 | 5.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Total no of medication prescriptions | 986 | 43.2 | 484 | 21.2 | 811 | 35.6 |

| Entered under ‘Zero Code’ | 76 | 7.7 | 46 | 9.5 | 121 | 14.9 |

| Total no of ‘Review of Systems’ and ‘Physical Exam’ annotations | 3421 | 78.0 | 964 | 22.0 | Not applicable† | |

| Entered into ‘Other’ categories | 137 | 4.0 | 43 | 4.5 | Not applicable† | |

The percentage cells in the ‘Total no’ rows report the proportion distribution across the three user types, and the percentage cells in the exit strategy rows report the ratio of data entered through the exit strategy by users of the respective clinician type groups.

The nurse and PA users' clinical role did not involve the documentation of RSPE findings.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported in part by Grant #D28HP10107 received from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and Grant # UL1RR024986 received from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board, the Western Pennsylvania Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA 2005;293:1197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han YY, Carcillo JA, Venkataraman ST, et al. Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system. Pediatrics 2005;116:1506–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sittig DF, Ash JS, Zhang J, et al. Lessons from ‘Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system’. Pediatrics 2006;118:797–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell EM, Sittig DF, Ash JS, et al. Types of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:547–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Poon EG, et al. The extent and importance of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14:415–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niazkhani Z, Pirnejad H, Berg M, et al. The impact of computerized provider order entry (CPOE) systems on inpatient clinical workflow: a literature review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:539–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Research Council Computational Technology for Effective Health Care: Immediate Steps and Strategic Directions. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartzband P, Groopman J. Off the record—avoiding the pitfalls of going electronic. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1656–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiff GD, Bates DW. Can electronic clinical documentation help prevent diagnostic errors? N Engl J Med 2010;362:1066–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenbloom ST, Denny JC, Xu H, et al. Data from clinical notes: a perspective on the tension between structure and flexible documentation. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:181–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13–22 [Google Scholar]