Abstract

Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is a heterogeneous disease of the bone marrow characterized by abnormal growth, accumulation and activation of clonal mast cells (MCs). We report a case of SM with multi-organ involvement. A 30-year-old man presented with diarrhea, flushing, maculopapular rash with itching and weight loss. The upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies showed macroscopic involvement of stomach and duodenum; mucosal samples from stomach, duodenum, colon and distal ileum showed mucosal infiltration by large, spindle-shaped MCs with abnormal surface molecule expression (CD2 and CD25), a picture fully consistent with SM, according to the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria. A computed tomography scan showed diffuse lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly and diffuse small bowel involvement. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy were diagnostic for SM; serum tryptase levels were increased (209 ng/mL, normal values < 20 ng/mL). The conclusive diagnosis was smouldering SM. There were no therapeutic indications except for treatment of symptoms. The patient was strictly followed up because of the risk of aggressive evolution.

Keywords: Mast cells, Systemic mastocytosis, Bone marrow, Tryptase

INTRODUCTION

Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is a heterogeneous disease of the bone marrow characterized by abnormal growth, accumulation and activation of clonal mast cells (MCs)[1-3]. In most patients, SM is caused by mutations in the KIT oncogene (D816V, present in more than 80% of patients), which encodes for a tyrosine kinase protein involved in differentiation and proliferation of MCs. This mutation determines an abnormal differentiation, proliferation and clustering of neoplastic progenitors of MCs[1-8]. Clinical features are related to histamine release (e.g., flushing, urticaria, itching, diarrhea, etc) or to uncontrolled growth and infiltration of clonal MCs in different organs (such as liver, spleen and bone marrow). The latter clinical findings must be divided into B- (Borderline Benign-Be watchful) and C-symptoms (Consider Cytoreductive therapy) (Table 1)[2-5].

Table 1.

Systemic mastocytosis findings related to mast cell infiltration and proliferation (modified from Valent et al[3])

| B symptoms (Borderline benign-be watchful) |

| Hepatomegaly |

| Splenomegaly |

| Lymphadenopathy |

| Hypercellular marrow |

| Mast cell infiltration in bone marrow > 30% |

| Serum tryptase levels > 200 ng/mL |

| C symptoms (Consider cytoreductive therapy) |

| Anemia (Hb < 10 g/dL) |

| Thrombocytopenia (< 100 000/mm3) |

| Neutropenia |

| Hepatopathy with ascites or portal hypertension |

| Splenomegaly with hypersplenism |

| Malabsorption with weight loss |

| Osteolysis with pathological bone fractures |

Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy represent the main diagnostic step when SM is suspected[1-5,7,8]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria (Table 2), SM is diagnosed when the major and at least one minor criterion or three minor criteria are satisfied[2,3].

Table 2.

World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for systemic mastocytosis (modified from Valent et al[3])

| Major criterion |

| Multifocal dense infiltrates of MCs (> 15 MCs in aggregates) in bone marrow biopsy and/or in sections of other extracutaneous organ(s) |

| Minor criteria |

| (1) > 25% of all MCs are atypical cells on bone marrow smears or are spindle-shaped in MC infiltrates detected on sections of extracutaneous organ(s) |

| (2) c-kit point mutation at codon 816 in the bone marrow or in another extracutaneous organ |

| (3) MCs in the bone marrow or in another extracutaneous organ express CD2 and/or CD25 |

| (4) Serum tryptase levels > 200 ng/mL (this criterion is valid only if AHNMD-SM has been excluded) |

MCs: Mast cells; AHNMD-SM: Associated hematopoietic clonal non-MC lineage disease systemic mastocytosis.

At present there is no effective therapy for SM and the medical approach is aimed at symptomatic relief and improvement of quality of life. SM patients should avoid triggers for MC degranulation (e.g., exposure to heat, cold, acute emotional stress, very strenuous exercise, alcohol). Commonly used symptomatic drugs are H1 and H2 histamine receptor blockers, ketotifen, cromolyn sodium and anti-leukotriene drugs. Cytoreductive regimens (interferon alpha-2b, cladribine, tyrosine kinase inhibitors and hydroxyurea) are indicated in SM with C findings[2-5,7-13].

CASE REPORT

A 30-year-old man presented with a ten-year history of maculopapular rash with itching and a six-month history of diarrhea (3-4 bowel movements per day with loose stools), flushing and weight loss.

The medical history was otherwise unremarkable, except for a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced anaphylaxis.

Relevant findings at physical examination were represented by a diffuse maculopapular rash with itching (termed “urticaria pigmentosa”) (Figure 1), hepatomegaly (with the lower hepatic edge 3 cm below the costal margin), splenomegaly (with the lower splenic edge 2 cm below the costal margin) and a diffuse, superficial, painless lymphadenopathy, ranging from 2 to 4 cm in diameter.

Figure 1.

Maculopapular rash (“urticaria pigmentosa”) in a systemic mastocytosis patient.

Complete blood count, renal function tests, plasma electrolytes, liver function tests, clotting and thyroid function tests were normal as was plasma protein gel electrophoresis.

Serological and stool tests for bacterial and parasitic infections were negative. Past or current hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections were ruled out by determining HBsAg and anti-HBc, anti-HCV and anti-HIV antibodies. Celiac disease was excluded on the basis of negative anti-endomysial and anti-transglutaminase antibodies with normal total IgA concentration. The panel for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors was negative. Serum calcitonin levels were normal. Conversely, serum tryptase level was 209 ng/mL (reference value ≤ 20 ng/mL).

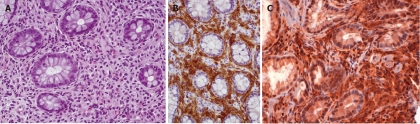

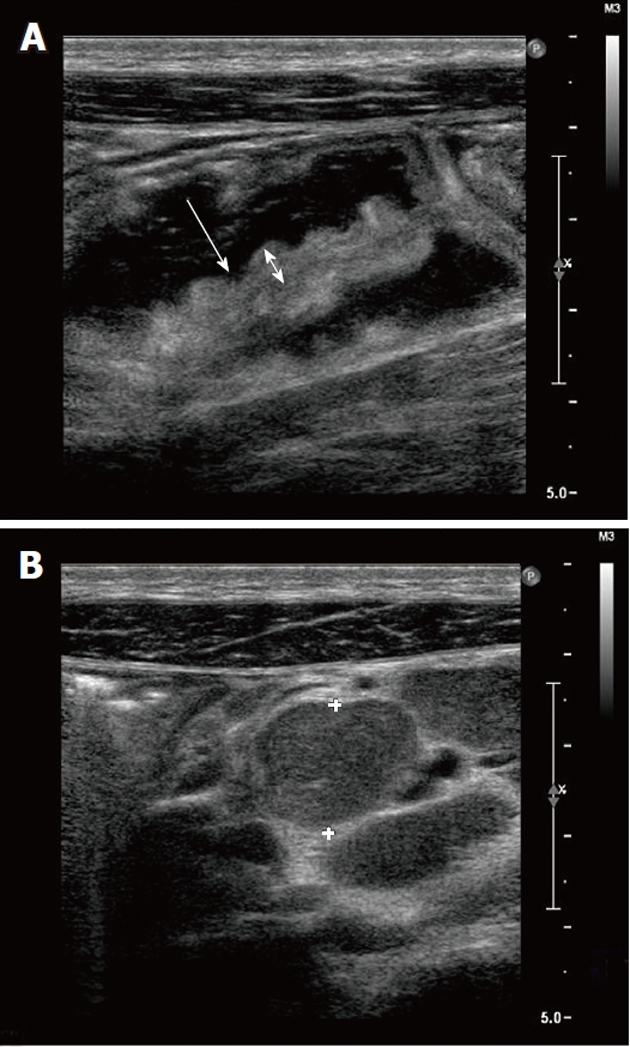

Abdominal ultrasonography showed hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, diffuse lymphadenopathy and diffuse small bowel dilatation with wall edema (Figure 2A and 2B). At upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy, there was a diffuse hyperemia with superficial erosions. Gastric, duodenal, distal ileal and colonic histology (Figure 3A, 3B and 3C) revealed diffuse mucosal MC infiltration, with spindle-shape and with abnormal surface molecule expression (CD2 and CD25) fully consistent with SM according to WHO criteria[2,3].

Figure 2.

Abdominal ultrasound. A: Small bowel dilatation and wall edema at ultrasonography (US). B: Abdominal lymphadenopathy at US (crosses refer to lymph node enlargement, 5 cm).

Figure 3.

Colon biopsy in a systemic mastocytosis patient. A: Diffuse mast cell (MC) infiltrate (Hematoxylin-eosin, × 10); B: The dense infiltrate is represented by MCs, whose detection is increased by positive immunohistochemical marker CD117; C: The dense infiltrate is represented by MCs, whose detection is increased by positive immunohistochemical marker CD25.

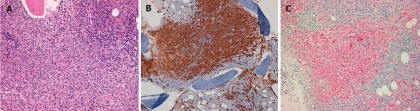

In line with the current guidelines[1-3,5], the patient underwent a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy with evidence of diffuse MC infiltration, fully consistent with SM (Figure 4A, 4B and 4C). D816V mutation detection in the KIT oncogene was negative.

Figure 4.

Bone marrow biopsy in a systemic mastocytosis patient. A: Diffuse mast cell (MC) infiltrate (Hematoxylin-eosin, × 10); B: The dense infiltrate is represented by MCs, whose detection is increased by positive immunohistochemical marker CD117; C: The dense infiltrate is represented by MCs, whose detection is increased by positive immunohistochemical marker CD25.

Disease staging was performed by both total body computed tomography scan, which confirmed hepatosplenomegaly, diffuse abdominal lymphadenopathy and diffuse small bowel involvement, and total skeleton X-ray, negative for osteolytic lesions. Osteoporosis was diagnosed on the basis of reduced bone mineral density.

In accordance with the diffuse organ involvement, serum tryptase levels > 200 ng/mL and B-findings (hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, diarrhea and osteoporosis), the final diagnosis was of smouldering SM[2-4]. No indication was given for cytoreductive regimen; the patient was instructed to avoid MC degranulation triggers and was given H1-H2 histamine receptor blockers and cromolyn sodium. A strict follow-up was planned aimed at early recognition of an aggressive SM evolution[2-4,7,8,14]. The patient was evaluated at quarterly intervals for a nine-month period and then, because of clinical stability, twice a year.

DISCUSSION

Systemic mastocytosis, a rare disease whose prevalence is unknown, can affect people at any age, with a slightly higher frequency in young men[1-3].

According to the WHO classification, four SM variants have been identified[1-3,5]: (1) indolent SM represents the most common form and is characterized by cutaneous and bone marrow involvement, without B or C findings; its prognosis is usually good. A rare subvariant, possibly progressing to a more aggressive SM type, is smouldering SM, characterized by B findings, diffuse organ involvement and serum tryptase levels > 200 ng/mL; (2) aggressive SM: this form affects 5% of SM patients and is characterized by the lack of cutaneous involvement. C findings are present and the prognosis is usually poor; (3) associated hematopoietic clonal non-MC lineage disease SM (AHNMD-SM) represents the second most frequent subtype of SM. To be diagnosed, WHO criteria for both SM and AHNMD must be fulfilled. Underlying blood disease is represented by myeloid disease in 80%-90% of cases and by lymphatic malignancy in the remaining 10%-20%. The prognosis is influenced both by AHNMD and SM subtype; and (4) mast cell leukemia: a very rare SM subtype characterized by C findings, percentage of neoplastic MCs at bone marrow biopsy > 20% and circulating neoplastic MCs. Its prognosis is usually poor.

As indicated by WHO diagnostic criteria, SM is diagnosed when the major criterion and at least one minor criterion or at least three minor criteria are satisfied[2,3]. Based on the low disease prevalence and its wide clinical spectrum, SM can be difficult to diagnose.

Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy represent the cornerstones for SM diagnosis, the hallmark being the presence of multifocal, dense MC aggregates[2,3]. To further improve MC recognition in bone marrow samples, immunohistochemical markers have been introduced. Among them, tryptase reactivity is considered the most sensitive, allowing the detection of even small MC infiltrates[15,16]. Considering that virtually all MCs, irrespective of their maturation stage, activation status or tissue of localization, express tryptase, staining for this marker detects even those infiltrates that are primarily comprised of immature, nongranulated MCs[17]. However, it must be emphasized that neither tryptase nor other immunohistochemical markers (e.g., CD 117) can distinguish between normal and neoplastic MCs[18]. Conversely, immunohistochemical detection of aberrant CD2 or CD25 expression on bone marrow MCs appears to be a reliable diagnostic tool in SM, given its ability to detect abnormal MCs in all SM subtypes[17]. The expression of even one of these two antigens represents a WHO minor diagnostic criterion.

Johnson et al[19] enrolled 59 patients with clinically suspected SM; all of them underwent bone marrow examination, including immunophenotyping by immunochemistry and/or flow cytometry and molecular studies for KIT exon 17 mutations, and determination of serum tryptase level. Using the WHO criteria, in patients with suspected SM based on clinical and laboratory findings, the diagnosis of SM was possible in 90% of the cases. However, the major criterion was only observed in nearly 70% of patients. In an additional 30%, the diagnosis of SM could only be obtained by using ancillary testing, as specified by the WHO minor criteria. Noteworthy, the series from Johnson et al[19] support the relevance of ancillary testing in obtaining the diagnosis of SM by bone marrow examination.

A further comment is warranted regarding the controversial role of serum tryptase level in the diagnostic SM algorithm. Tryptase is an enzyme stored in MC granules and released after MC degranulation. It is activated by acidic pH and presence of heparin. The biologic activity of enzymatically active tryptase is still uncertain. Many potential substrates have been defined in vitro: anticoagulation, fibrosis and fibrolysis, kinin generation and destruction, enhancement of vascular permeability, airway smooth muscle hyperreactivity. However, it must be underlined that the in vivo relevance of these potential activities remains to be defined. Serum tryptase levels increase as a consequence of acute systemic anaphylaxis, SM and myeloproliferative diseases. In SM, serum tryptase levels represent a minor diagnostic criterion according to the WHO, but only if AHNMD-SM has been excluded[20,21]. Valent et al[3,5] have recently suggested that patients with clinical suspicion of SM having high serum tryptase levels should undergo a bone marrow examination in order to confirm the diagnosis. Furthermore, as tryptase levels are related to the burden of neoplastic MCs, their determination is of relevance in following up those SM patients given a cytoreductive regimen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank “Associazione Amici della Gastroenterologia del Granelli” for its continuous support.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Jean Paul Galmiche, MD, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Hôpital Hôtel Dieu, 44093 Nantes Cedex, France

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Horny HP, Sotlar K, Valent P. Mastocytosis: state of the art. Pathobiology. 2007;74:121–132. doi: 10.1159/000101711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen T. Rare hematological malignancies. 9th ed. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 399–419. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, Horny HP, Arock M, Lechner K, Bennett JM, Metcalfe DD. Diagnosis and treatment of systemic mastocytosis: state of the art. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:695–717. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hungness SI, Akin C. Mastocytosis: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7:248–254. doi: 10.1007/s11882-007-0037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valent P, Akin C, Escribano L, Födinger M, Hartmann K, Brockow K, Castells M, Sperr WR, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hamdy NA, et al. Standards and standardization in mastocytosis: consensus statements on diagnostics, treatment recommendations and response criteria. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:435–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim KH, Pardanani A, Tefferi A. KIT and mastocytosis. Acta Haematol. 2008;119:194–198. doi: 10.1159/000140630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pardanani A, Akin C, Valent P. Pathogenesis, clinical features, and treatment advances in mastocytosis. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2006;19:595–615. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, Mayerhofer M, Födinger M, Fritsche-Polanz R, Sotlar K, Escribano L, Arock M, Horny HP, et al. Mastocytosis: pathology, genetics, and current options for therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:35–48. doi: 10.1080/10428190400010775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kluin-Nelemans HC, Oldhoff JM, Van Doormaal JJ, Van ‘t Wout JW, Verhoef G, Gerrits WB, van Dobbenburgh OA, Pasmans SG, Fijnheer R. Cladribine therapy for systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2003;102:4270–4276. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim KH, Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Finke C, Patnaik M, Butterfield JH, McClure RF, Li CY, Pardanani A. Systemic mastocytosis in 342 consecutive adults: survival studies and prognostic factors. Blood. 2009;113:5727–5736. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pardanani A, Elliott M, Reeder T, Li CY, Baxter EJ, Cross NC, Tefferi A. Imatinib for systemic mast-cell disease. Lancet. 2003;362:535–536. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pardanani A, Tefferi A. Systemic mastocytosis in adults: a review on prognosis and treatment based on 342 Mayo Clinic patients and current literature. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:125–132. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283366c59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tefferi A, Li CY, Butterfield JH, Hoagland HC. Treatment of systemic mast-cell disease with cladribine. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:307–309. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101253440415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pardanani A, Lim KH, Lasho TL, Finke CM, McClure RF, Li CY, Tefferi A. WHO subvariants of indolent mastocytosis: clinical details and prognostic evaluation in 159 consecutive adults. Blood. 2010;115:150–151. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horny HP, Sotlar K, Sperr WR, Valent P. Systemic mastocytosis with associated clonal haematological non-mast cell lineage diseases: a histopathological challenge. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:604–608. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.014860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horny HP, Valent P. Histopathological and immunohistochemical aspects of mastocytosis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;127:115–117. doi: 10.1159/000048180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sotlar K, Horny HP, Simonitsch I, Krokowski M, Aichberger KJ, Mayerhofer M, Printz D, Fritsch G, Valent P. CD25 indicates the neoplastic phenotype of mast cells: a novel immunohistochemical marker for the diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis (SM) in routinely processed bone marrow biopsy specimens. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1319–1325. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000138181.89743.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan JH, Walchshofer S, Jurecka W, Mosberger I, Sperr WR, Wolff K. Immunohistochemical properties of bone marrow mast cells in systemic mastocytosis: evidence for expression of CD2, CD117/Kit, and bcl-x(L) Hum Pathol. 2001;32:545–552. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.24319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson MR, Verstovsek S, Jorgensen JL, Manshouri T, Luthra R, Jones DM, Bueso-Ramos CE, Medeiros LJ, Huh YO. Utility of the World Heath Organization classification criteria for the diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis in bone marrow. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:50–57. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brockow K, Akin C, Huber M, Scott LM, Schwartz LB, Metcalfe DD. Levels of mast-cell growth factors in plasma and in suction skin blister fluid in adults with mastocytosis: correlation with dermal mast-cell numbers and mast-cell tryptase. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:82–88. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.120524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz LB. Diagnostic value of tryptase in anaphylaxis and mastocytosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]