Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Despite advances in treatment, patients with migraine have been underdiagnosed and undertreated, specifically in emergency departments. In addition, great variability exists with respect to the diagnosis, management and treatment of migraine patients in emergency departments. In particular, migraine-specific treatments, including serotonin receptor agonists, appear to be rarely used.

OBJECTIVE:

To examine the diagnosis and management of migraine patients within Ontario emergency departments.

METHODS:

A prospective survey was designed to inquire how emergency physicians diagnose and manage patients with migraine. Questions focused on the use of serotonin receptor agonists, the rationale behind their use or nonuse, and acute headache protocols. The survey also inquired about the use of International Classification Of Headache Disorders-2 criteria in diagnosing migraine by emergency physicians, medication prescribed on discharge, and referrals made to outpatient specialists. These surveys were distributed to and anonymously completed by emergency physicians in several departments in Ontario.

RESULTS:

Migraine-specific treatments were underused in emergency departments. Furthermore, many departments lacked headache protocols and, often, migraine-specific treatment was not included in the few departments with protocols.

CONCLUSIONS:

Diagnosis and management of migraines can be improved within emergency departments, and patients can be more effectively channelled toward appropriate outpatient care.

Keywords: Emergency department, Migraine, Triptans

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Malgré les progrès thérapeutiques, les patients migraineux sont sous-diagnostiqués et sous-traités, notamment à l’urgence. De plus, on constate une importante variabilité à l’égard du diagnostic, de la prise en charge et du traitement des patients migraineux aux départements d’urgence. Notamment, les traitements propres à la migraine, y compris les agonistes des récepteurs de la sérotonine, semblent rarement utilisés.

OBJECTIF :

Examiner le diagnostic et la prise en charge des patients migraineux dans des départements d’urgence de l’Ontario.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Une enquête prospective a été conçue pour déterminer comment les médecins d’urgence diagnostiquent et prennent en charge les patients migraineux. Les questions portaient sur l’utilisation des agonistes des récepteurs de la sérotonine, la raison de leur utilisation ou de leur non-utilisation et les protocoles sur les céphalées aiguës. L’enquête portait également sur l’utilisation que font les urgentologues des critères de la classification internationale des troubles céphaliques 2 pour diagnostiquer la migraine, sur les médicaments prescrits au congé et sur les aiguillages vers des spécialistes en santé ambulatoire. Cette enquête a été distribuée à des urgentologues de plusieurs départements de l’Ontario, et ceux-ci y ont répondu de manière anonyme.

RÉSULTATS :

Les traitements propres à la migraine étaient sous-utilisés aux départements d’urgence. De plus, de nombreux départements ne disposaient pas de protocoles sur les céphalées, et souvent, les traitements propres à la migraine n’étaient pas inclus dans les protocoles des quelques départements en disposant.

CONCLUSIONS :

Le diagnostic et la prise en charge des migraines peuvent être améliorés aux départements d’urgence, et les patients peuvent être orientés de manière plus efficace vers les soins ambulatoires pertinents.

In the United States, 1% of all emergency department visits are for the chief complaint of headache (1). Despite advances in treatment, patients with migraine have been underdiagnosed and undertreated, specifically in emergency departments (2). In addition, great variability exists with respect to diagnosis and management of migraine patients in emergency departments (3). Migraine International Classification Of Headache Disorders (ICHD)-2 criteria are often not used by emergency physicians (1).

Historically, two approaches have been used in migraine treatment: step care and stratified care. Step care management involves escalating medication after first-line treatments fail (4). In stratified care, the initial treatment is based on a measurement of the severity of migraine and disability (4). Many physicians commonly use step care in approaching headache patients (5). However, the Disability In Strategies of Care (DISC) study (4) demonstrated that stratified care is more effective than step care as measured by headache response and disability time.

Within emergency departments, treatment is migraine specific in only a minority of patients (1,6). In particular, serotonin receptor agonists appear to be underused (7,8). The need for prophylaxis is not usually assessed in emergency departments (9). Many patients leave without a discharge diagnosis, outpatient medications or instructions (9,10).

The present study examined the management of migraines within Ontario emergency departments. By prospectively surveying emergency physicians, we attempted to identify the rationale for treatment, and deficiencies in diagnosis, management and prophylaxis. Improving existing protocols may enable more effective care in the future for patients experiencing migraines.

METHODS

A prospective survey was designed to inquire how emergency physicians manage patients with migraine (Appendix A). The survey was divided into three groups of questions: diagnosis, management and discharge of migraine patients. With respect to migraine management, questions were focused on the use of abortive therapies and acute headache protocols. The survey also inquired about the use of ICHD-2 criteria in the diagnosis of migraine by emergency physicians, the medication prescribed on discharge and referrals made to outpatient specialists. Approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Board for the Toronto Academic Health Sciences Network. A list of all licensed Ontario emergency physicians and their addresses was obtained from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. Surveys were distributed to and anonymously completed by emergency physicians, and returned via labelled postage-paid envelopes to the Wasser Pain Management Centre of Mount Sinai Hospital (Toronto, Ontario). Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS software (IBM Corporation, USA).

RESULTS

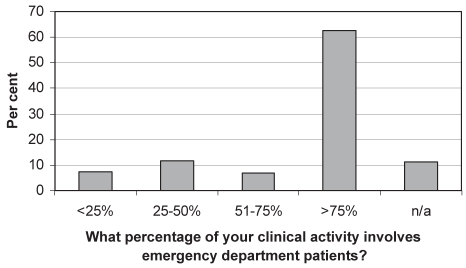

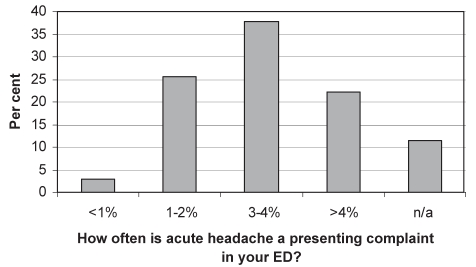

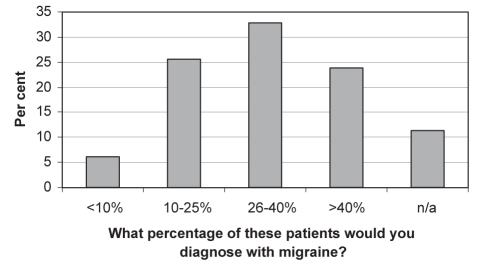

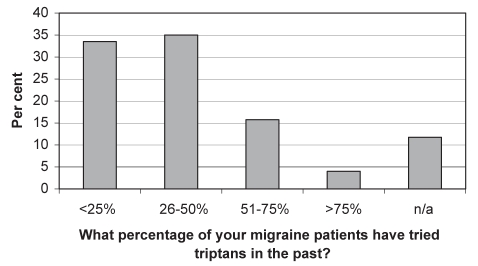

Of the surveys mailed to Ontario emergency physicians (n=1043), 311 were completed and returned, yielding a response rate of 30%. When asked what percentage of their clinical activity involved emergency patients, 62.7% of physicians indicated greater than 75% (Question A.1). Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of responses to this question. Approximately 38% of physicians reported that 3% to 4% of patients encountered in the emergency department presented with acute headache (Figure 2). Twenty-two per cent of physicians reported the number to be even higher at greater than 4% (Figure 2). Migraine is diagnosed, in these cases, more than 40% of the time according to approximately 24% of surveyed physicians, and between 26% and 40% of the time according to approximately 33% (Figure 3). Only approximately 26% of responding emergency physicians reported using the International Headache Society criteria for the diagnosis of migraine (Question A.4). Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of responses pertaining to triptan medication use history among migraine patients. Approximately 69% of surveyed physicians answered that less than 50% of migraine patients had tried triptans (Figure 4).

Figure 1).

Distribution of responses to question A.1. n/a Not answered

Figure 2).

Distribution of responses to question A.2. ED Emergency department; n/a Not answered

Figure 3).

Distribution of responses to question A.3. n/a Not answered

Figure 4).

Distribution of responses to question A.5. n/a Not answered

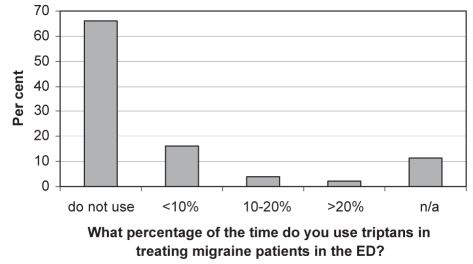

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of emergency physicians’ responses regarding their use of triptans in treating migraine patients. Approximately 66% of respondents reported that they did not use triptans. Table 1 summarizes the varying responses pertaining to the rationale for not using triptans. The most commonly selected justification among approximately 45% of emergency physicians was due to lack of availability secondary to protocol/formulary issues (Table 1). Only approximately 15% of emergency physicians reported that they had a standardized headache protocol in their emergency department (Question B.3). In the few departments with headache protocols, approximately 16% reported the inclusion of antiemetics, 11% included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, 9% included ergotamines, 2% included opiates and less than 1% included triptans (Question B.4).

Figure 5).

Distribution of responses to question B.1. ED Emergency department; n/a Not answered

TABLE 1.

Distribution of responses to question B.2

| Rationale for nonuse of triptans | Percentage of respondents selecting option |

|---|---|

| Not available due to protocol/formulary | 45.1 |

| Uncertainty of evidence and/or presence of alternatives | 20.0 |

| Uncertainty regarding follow-up | 10.2 |

| Too late for abortive therapy | 4.1 |

| Prior failure of triptan use | 3.1 |

| Cost | 1.7 |

| Side effects and/or contraindications | 1.4 |

| Lack of familiarity | 0.3 |

| Not answered | 13.6 |

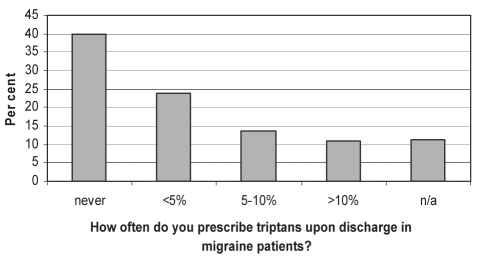

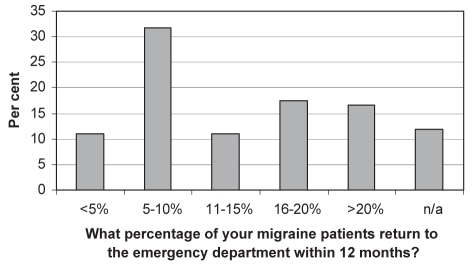

With respect to discharge management, only approximately 22% of emergency physicians reported referring migraine patients to headache specialists or neurologists (Question C.1). Figure 6 demonstrates the distribution of responses pertaining to prescribing triptans on discharge from the emergency department. The most commonly selected response was that approximately 40% of emergency physicians never prescribed triptans on discharge (Figure 6). Finally, Figure 7 demonstrates the distribution of responses pertaining to the return of migraine patients to the emergency department within 12 months. Approximately 46% of emergency physicians reported that more than 10% of migraine patients would return within that period.

Figure 6).

Distribution of responses to question C.2. n/a Not answered

Figure 7).

Distribution of responses to question C.3. n/a Not answered

DISCUSSION

Our survey examined migraine diagnosis and management within Ontario emergency departments. Several areas requiring improvement were identified. Despite frequent encounters with migraine patients, it appears that ICHD-2 criteria are rarely used. Diagnostic imprecision can lead to generalized pain treatment instead of migraine-specific treatment (1). This may stem from emergency physicians focusing on ruling out secondary, often life-threatening, causes of headache (1).

Despite the fact that many migraine patients are severely disabled, opiates and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications were prescribed more commonly than migraine-specific therapies in emergency departments. It may be postulated that a step care approach by emergency physicians involves using opiates and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications as first-line treatments before triptans are used (6,11,12). It is possible that the high cost of triptans has also made it difficult to implement this therapy within emergency departments (3,6). However, it has been demonstrated that in patients stratified with severe migraines, management with migraine-specific treatments has been most effective for decreasing headache and disability (4). It is also apparent from our results that headache protocols can be improved to include such migraine-specific options. It is also important to consider that triptans are much more effective when used early in the course of migraine headaches (6). Revised protocols may also include an effective triage strategy to ensure that migraine-specific treatment is not delayed by wait times.

Our study reflected how prescriptions given on discharge rarely include migraine-specific medications for future abortive therapy (13). Similarly, prophylaxis was infrequently addressed and outpatient referrals to neurologists/headache specialists were not common. Undoubtedly, these contributed to the high frequency of return visits to the emergency department noted among migraine patients (10). It has been demonstrated that outpatient referrals and appropriate follow-up result in decreased future disability and more cost-effective care (10,14).

Results obtained from survey studies certainly lend themselves to limitations including recall bias. For example, the reported use of narcotics in our survey was much lower than results obtained from other retrospective studies (15). Certainly, retrospective studies could assist in comprehensively evaluating migraine management within emergency departments. The results of the present study are important because they highlight many areas of improvement required with respect to emergency migraine management. Additional studies and implementation of guidelines may optimize future care for patients with migraine.

CONCLUSIONS

Migraine management within Ontario emergency departments can be improved with respect to diagnosis and use of appropriate ICHD-2 criteria. Implementation of headache protocols that are centred on a stratified care form of management and include migraine-specific treatment would benefit many patients with significant disability (4). Improved attention to prophylaxis can reduce the economic and health care burden of migraine patients making recurring visits to the emergency department (10). Finally, more appropriate channelling to outpatient care, including referral to neurologists or headache specialists, is necessary (14).

APPENDIX A.

SURVEY CODE: ___________

Survey of Migraine Management Among Emergency Physicians in Ontario

- Diagnosis of Migraine

- What percentage of your clinical activities involve seeing emergency department patients?

- □ <25

- □ 25–50%

- □ 51–75%

- □ >75%

- How often is acute headache a presenting complaint in your emergency department?

- □ <1%

- □ 1–2%

- □ 3–4%

- □ >4%

- What percentage of these patients would you diagnose with migraine?

- □ <10%

- □ 10–25%

- □ 26–40%

- □ >40%

- Do you use the International Headache Society (IHS) Criteria?

- □ yes

- □ no

- What percentage of your migraine patients have tried triptans in the past?

- □ <25%

- □ 25–50%

- □ 51–75%

- □ >75%

- Management of Migraine

- How often do you use triptans in treating migraine patients in the emergency department?

- □ do not use

- □ <10%

- □ 10–20%

- □ >20%

- If you do not use triptans, what is your rationale?

- □ not available due to protocol/formulary

- □ uncertainty regarding follow-up

- □ uncertainty of evidence and presence of alternatives

- □ other ______________________________________

- Does your emergency department have a standardized headache protocol?

- □ yes

- □ no

- Which medications are included in this protocol (choose all that apply)?

- □ antiemetics

- □ opioids

- □ non-steroidal anti-inflammatories

- □ ergotamine

- □ triptans

- Discharge of Migraine Patients

- Do you refer migraine patients on discharge to headache specialists/neurologists?

- □ yes

- □ no

- How often do you prescribe triptans upon discharge in migraine patients?

- □ never

- □ <5%

- □ 5–10%

- □ >10%

- What is your best estimate of the percentage of migraine patients who have return visits to the emergency department within 12 months?

- □ <5%

- □ 5–10%

- □ 11–15%

- □ 16–20%

- □ >20%

Thank you for participating in our survey

Footnotes

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: This project was funded by a research grant provided by Pfizer Canada. The authors also thank the American Headache Society for its support via the 2009 American Headache Society Scholarship.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No authors have any conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta MX, Silberstein SD, Young WB, Hopkins M, Lopez BL, Samsa GP. Less is not more: Underutilization of headache medications in a university hospital emergency department. Headache. 2007;47:1125–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maizels M. Headache evaluation and treatment by primary care physicians in an emergency department in the era of triptans. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1969–73. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.16.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurtadao TR, Vinson DR, Vandenberg JT. ED treatment of migraine headache: Factors influencing pharmacotherapeutic choices. Headache. 2007;47:1134–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Stone AM, Lainez MJA, Sawyer JPC. Stratified care versus step care strategies for migraine. The disability in strategies of care (DISC) study: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2000;284:2599–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Korff M, Black LK, Saunders K, Galer BS. Headache medication-use among primary care headache patients in a health maintenance organization. Cephalagia. 1999;19:575–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019006575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ducros A. Emergency treatment of migraine. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(Suppl 2):9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pradalier A, Baudesson G, Delage A. Management of intractable migraine in adults. Therapie. 2003;58:317–25. doi: 10.2515/therapie:2003049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman BW, Corbo J, Lipton RB, et al. A trial of metoclopramide vs sumatriptan for the emergency department treatment of migraines. Neurology. 2005;64:463–8. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150904.28131.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwong WJ. Determinants of migraine emergency department utilization in the Georgia Medicaid population. Headache. 2007;47:1326–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maizels M. Health resource utilization of the emergency department headache “repeater”. Headache. 2002;42:747–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narbone MC, Abbate M, Gangemi S. Acute drug treatment of migraine attack. Neurol Sci. 2004;25(Suppl 3):S113–8. doi: 10.1007/s10072-004-0266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nijjar SS, Gordon A, Clark M. Entry demographics and pharmacological treatment of migraine patients referred to a tertiary care pain clinic. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:87–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinson DR, Hurtado TR, Vandenberg JT, Banwart L. Variations among emergency departments in the treatment of benign headache. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:90–7. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahai-Srivastava S, Desai P, Zheng L. Analysis of headache management in a busy emergency room in the United States. Headache. 2008;48:931–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colman I, Rothney A, Wright SC, Zikalns B, Rowe BH. Use of narcotic analgesics in the emergency department treatment of migraine headache. Neurology. 2004;62:1695–700. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000127304.91605.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]