Time to follow-up varies widely between facilities, suggesting potential for improvement by many facilities, and takes longer for biopsy or surgical consult recommendations than for additional imaging recommendations.

Abstract

Purpose:

To describe the timeliness of follow-up care in community-based settings among women who receive a recommendation for immediate follow-up during the screening mammography process and how follow-up timeliness varies according to facility and facility-level characteristics.

Materials and Methods:

This was an institutional review board–approved and HIPAA-compliant study. Screening mammograms obtained from 1996 to 2007 in women 40–80 years old in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium were examined. Inclusion criteria were a recommendation for immediate follow-up at screening, or subsequent imaging, and observed follow-up within 180 days of the recommendation. Recommendations for additional imaging (AI) and biopsy or surgical consultation (BSC) were analyzed separately. The distribution of time to follow-up care was estimated by using the Kaplan-Meier estimator.

Results:

Data were available on 214 897 AI recommendations from 118 facilities and 35 622 BSC recommendations from 101 facilities. The median time to subsequent follow-up care after recommendation was 14 days for AI and 16 days for BSC. Approximately 90% of AI follow-up and 81% of BSC follow-up occurred within 30 days. Facilities with higher recall rates tended to have longer AI follow-up times (P < .001). Over the study period, BSC follow-up rates at 15 and 30 days improved (P < .001). Follow-up times varied substantially across facilities. Timely follow-up was associated with larger volumes of the recommended procedures but not notably associated with facility type nor observed facility-level characteristics.

Conclusion:

Most patients with follow-up returned within 3 weeks of the recommendation.

© RSNA, 2011

Introduction

One critical patient group for a successful screening mammography program is the 10% of asymptomatic women in whom an abnormal mammogram, suggesting preclinical breast malignancy, is obtained. Additional imaging (AI) is conducted on screening-detected abnormalities to determine which ones are sufficiently suspicious to require biopsy. In the United States, of screened women who are recalled, about one in five will receive a recommendation for biopsy (1).

How promptly such recall to further evaluation, including biopsy, is conducted is crucial to a program’s success. Prompt evaluation minimizes a patient’s anxiety in regard to an abnormal screening mammogram, especially as most patients do not require biopsy (1). Prompt biopsy after a biopsy recommendation has even greater value. The European community has published their recommended guidelines for timeliness of follow-up on the basis of expert consensus (2), and to our knowledge, they are the only such published guidelines. Their acceptable outcomes are 95% of patients receiving a result within 15 working days and 90% offered the follow-up within 5 working days. These outcomes would correspond to at least a 4-week delay to follow-up. One national U.S. organization has undertaken to measure such timeliness as part of a quality assurance program (3) and is accumulating data, albeit using a self-selected group of reporting institutions. Reports are limited in regard to follow-up after screening, with most being issued from single institutions, some from regional data collection, and others reporting the effect of interventions in this process (4–14). We undertook this study because the current literature lacks a broad profile of facility timeliness measures in regard to the additional evaluation of patients with screening-detected abnormalities.

The follow-up process requires several steps, each of which may cause delays (15). At facilities in which only screening is performed, any studies with abnormal findings need referral elsewhere. But even if screening is performed and diagnostic mammograms are obtained at the radiology facility, delays may occur between imaging and interpretation, between interpretation and contact of patients, and between patient contact and the date of the scheduled follow-up procedure.

In follow-up of screening mammography with abnormal findings, completeness is essential, and timeliness is an important goal. For example, follow-up studies tend to be performed later in women of color or lower socioeconomic status (12,16). Identifying factors associated with reasons for delay in this cohort—and in all women—may provide a basis for quality improvement. At this time, there are little comparative data for facilities seeking a basis for self-evaluation.

The objective of this study was to describe the timeliness of follow-up care in community-based settings among women who received a recommendation for immediate follow-up during the screening mammography process and how follow-up timeliness varies according to facility and facility-level characteristics.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

The Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) is a collaborative network of population-based mammography registries with linkages to tumor registries (17). Analyses in this study are based on pooled data sent to the BCSC Statistical Coordinating Center (Seattle, Wash) from six registries in North Carolina, Western Washington State, New Hampshire, New Mexico, San Francisco, and Vermont. Each registry and the Statistical Coordinating Center received institutional review board approval for either active or passive consenting processes or a waiver of consent to enroll participants, link data, and perform analytic studies. All procedures were Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant.

Study Sample and Definition

We included women aged 40–80 years with a recommendation for AI or biopsy or surgical consultation (BSC) following screening mammography. We used the standard BCSC definition of screening mammography (18) as a bilateral examination indicated by the radiologist or technician to be for screening; we included examinations performed between January 1996 and December 2007. Examinations from women who had a prior diagnosis of breast cancer were excluded (19), as they are not universally considered as screening examinations.

We considered two types of abnormal recommendations: (i) a recommendation for immediate AI on the basis of the findings on routine screening views and (ii) a final recommendation for fine-needle aspiration or BSC at the end of imaging work-up and within 90 days following the initial screening examination. For AI recommendations, we looked forward 180 days from the date of the screening mammogram for evidence of an ultrasonographic (US) examination and/or diagnostic mammography. For BSC recommendations, we looked forward 180 days from the date of the final assessment for evidence of fine-needle aspiration or BSC from our radiology follow-up and pathology databases.

Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System assessments were not used to define a recommendation for AI or BSC because Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System assessments do not always match the recommendations associated with the assessment (20,21).

The final study sample consisted of recommendations for immediate follow-up for which follow-up care within 180 days was observed. Of 296 364 AI records, 81 467 (27.5%) were excluded because of no observed follow-up. Of the 54 642 BSC records, 19 020 (34.8%) were excluded because of no observed follow up. Observations for which follow-up was performed on the same day or no follow-up care was observed within 180 days were excluded because the purpose of the analysis was to describe the time to follow-up in women we knew returned for care. Women receiving follow-up care on the same day we already knew had no time between screening and care. Finally, as the primary aim of this work was to characterize variability across facilities, and have a broad representation of facilities, we further restricted analyses of AI recommendations to facilities with at least 50 observations and analyses of biopsy recommendations to facilities with at least 20 observations. This restriction balances broad facility representation, while it minimizes variability from small numbers. The censoring of the few cases beyond 180 days was necessary to increase the probability that the follow-up event was the result of the screening event.

Woman- and Facility-Level Characteristics

At the time of each screening mammographic examination, each woman completed a questionnaire that requested information on age, race, ethnicity, education, self-reported presence of breast problems, personal history of mammography (time since last screening mammogram), and personal and first-degree family histories of breast cancer.

Available facility-level characteristics included facility type (Table 1, groups) and five characteristics that were based on aggregated information on mammographic examinations from each facility: (i) mean percentage rural residence of the population served, which was based on geocoded linkage between 2000 census data and self-reported residential zip code (22); (ii) overall volume, which was based on results of all mammographic examinations (screening and diagnostic); (iii) annualized overall volume, calculated as the overall volume divided by the number of months for which data were contributed and multiplied by 12; (iv) number of women recalled; and (v) percentage of women recalled. The latter two facility-level characteristics were based solely on screening mammographic examinations; examinations with initial Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System assessments of category 1, 2, or 3 with no recommendation for immediate follow-up were considered negative; all other assessment and recommendation combinations were taken to be positive (18).

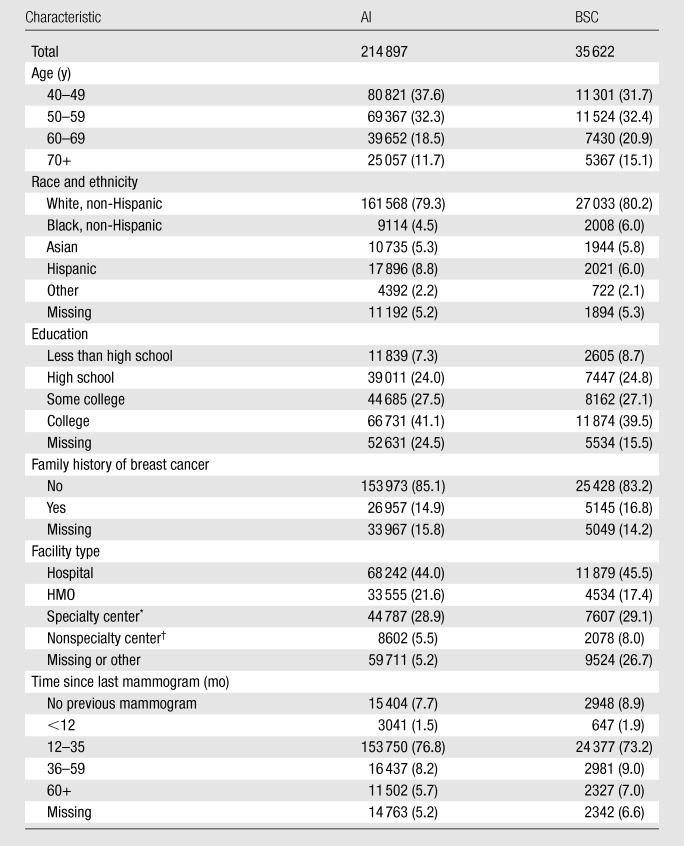

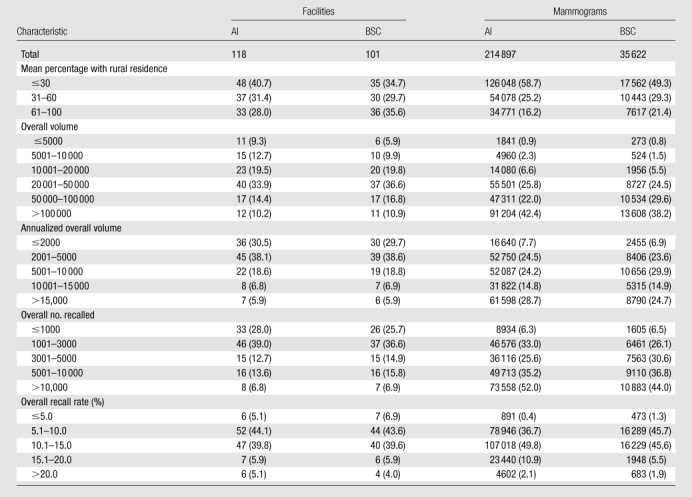

Table 1.

Mammogram-Level Characteristics according to Type of Recommendation

Note.—Data are numbers of mammograms, and numbers in parentheses are column percentages, calculated over recommendations for which the characteristic is nonmissing. Percentages were rounded. HMO = health maintenance organization.

Radiology private office or hospital outpatient center.

Obstetrics and gynecology office, primary care office, or multispeciality clinic.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated simple metrics similar to those presented in the European guidelines (2), which facilities can perform and are clinically relevant: percentage of follow-up accomplished at 15 and 30 days, in women with known follow-up within 180 days. Kaplan-Meier survival plots were constructed to characterize the follow-up process. We examined follow-up rates according to facility and patient characteristics and also explored changes over the observed study period of 1996–2007. Throughout, our analyses were stratified according to the type of recommendation. Given our definitions, it is possible that a single mammographic episode contributes to analyses for both types of recommendations. All analyses were conducted by using statistical software (SAS 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and software for computing (R 2.10; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). In this large data set, many differences were significant at P < .01 or P < .001 but may not be important for patient care. For example, single-day differences in the delay of follow-up between facility types would not be considered clinically important. To identify larger more important differences most worthy of comment, we used the term “notable” or “notably.” All of these differences also signify differences with P < .01. While it is tempting to create a percentage difference that qualifies as “notable,” each comparison has different clinical implications so a single “notable” percentage is not possible.

Our study population is a subset of the larger BCSC population, which has been used widely in publications, including a prior study from the New Mexico Mammography Project in which the timeliness of follow-up was examined (14,23).

Results

Our study sample consisted of 214 897 AI recommendations and 35 622 BSC recommendations (Table 1). As has previously been shown, women attending BCSC facilities have racial, ethnic, and urban-rural characteristics similar to those of the U.S. population (1), except for a lower representation of African Americans (Table 1). Of the AI recommendations with nonmissing time since last screening mammogram, 78.3% (156 791 of 200 134) were in women in whom a prior mammogram was obtained within 35 months of the screening mammogram; of the BSC recommendations with nonmissing time since the last screening mammogram, 75.2% (25 024 of 33 280) were in women in whom a prior mammogram was obtained within 35 months of the initial screening mammogram. Of the AI recommendations with nonmissing self-reported family history of breast cancer, 14.9% (26 957 of 180 930) reported a positive family history; of the BSC recommendations, the rate was somewhat higher at 16.8% (5145 of 30 573). Most women were imaged at a hospital facility, and most women had at least some college education.

The AI recommendations in our sample were measured at 118 facilities, while the BSC recommendations were measured at a subset of 101 facilities (Table 2). These 118 facilities represent 1.19% (118 of 9933) of the operating facilities in the United States in 2000 and 1.34% (118 of 8832) of the operating facilities in 2006 (24). The annualized mammogram volumes represented in this report vary substantially from less than 5000 per year to more than 100 000 per year. Most facilities serve an urban population, but 28.0% of the facilities serve a mostly rural population.

Table 2.

Distributions of Facilities and Mammograms across Facility-Level Characteristics according to Type of Recommendation

Note.—Data are numbers of facilities (AI and BSC columns under Facilities) and numbers of mammograms (AI and BSC columns under Mammograms), and numbers in parentheses are column percentages. Percentages were rounded.

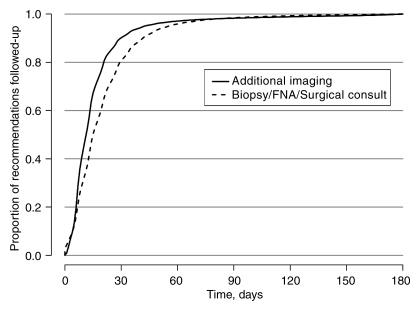

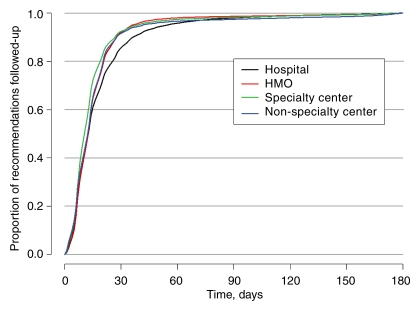

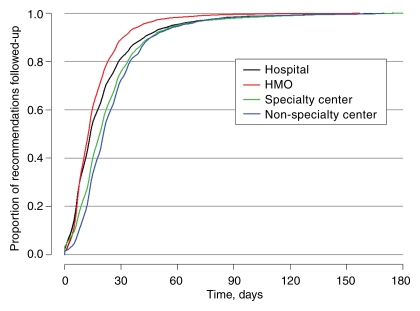

Among those observed to receive subsequent care within 180 days of the recommendation, the time to follow-up for BSC consistently exceeded that for AI (Fig 1). Approximately 90% of AI follow-up and 81% of BSC follow-up occurred within 30 days (Fig 1). The median time to follow-up was 14 days for AI and 16 days for BSC. The observed time to AI follow-up according to facility type demonstrated significantly (P < .001) longer times for hospital-based screening, but the longest notably different times for BSC were in specialty and nonspecialty centers and the shortest times were in HMO-type facilities (Figs 2, 3).

Figure 1:

Kaplan-Meier plot of the timing of receipt of care following AI and BSC recommendations, given receipt occurred within 180 days of the date of the recommendation. FNA = fine-needle aspiration.

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier plot of the timing of receipt of care following an AI recommendation, given receipt occurred within 180 days of the date of the recommendation, stratified according to facility type.

Figure 3:

Kaplan-Meier plot of the timing of receipt of care following a BSC recommendation, given receipt occurred within 180 days of the date of the recommendation, stratified according to facility type.

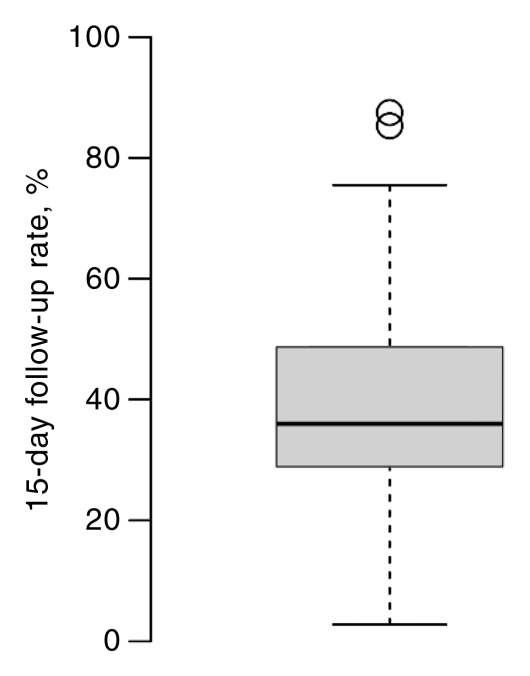

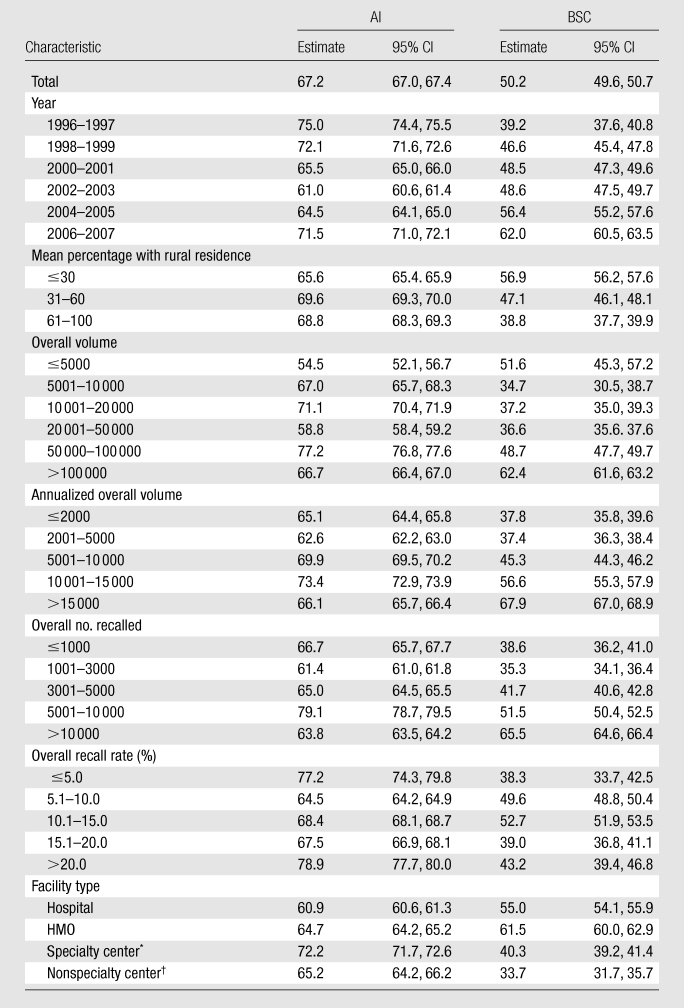

The fraction of women with AI completed by 15 days decreased by 13% between 1996–1997 and 2002–2003, but it nearly recovered to the initial performance by 2006–2007 (Tables 3, 4). The completion rate of BSC at 15 days showed a different pattern, with continued and large improvements between 1996–1997 and 2006–2007. In the earliest years for BSC by 15 days, 40% of patients had undergone follow-up, while in 2006–2007 more than 60% had undergone follow-up.

Table 3.

15-Day Follow-up Rates according to Type of Recommendation and across Facility-Level Characteristics among Women Who Returned within 180 Days

Note.—All data are percentages. CI = confidence interval.

Radiology private office or hospital outpatient center.

Obstetrics and gynecology office, primary care office, or multispecialty clinic.

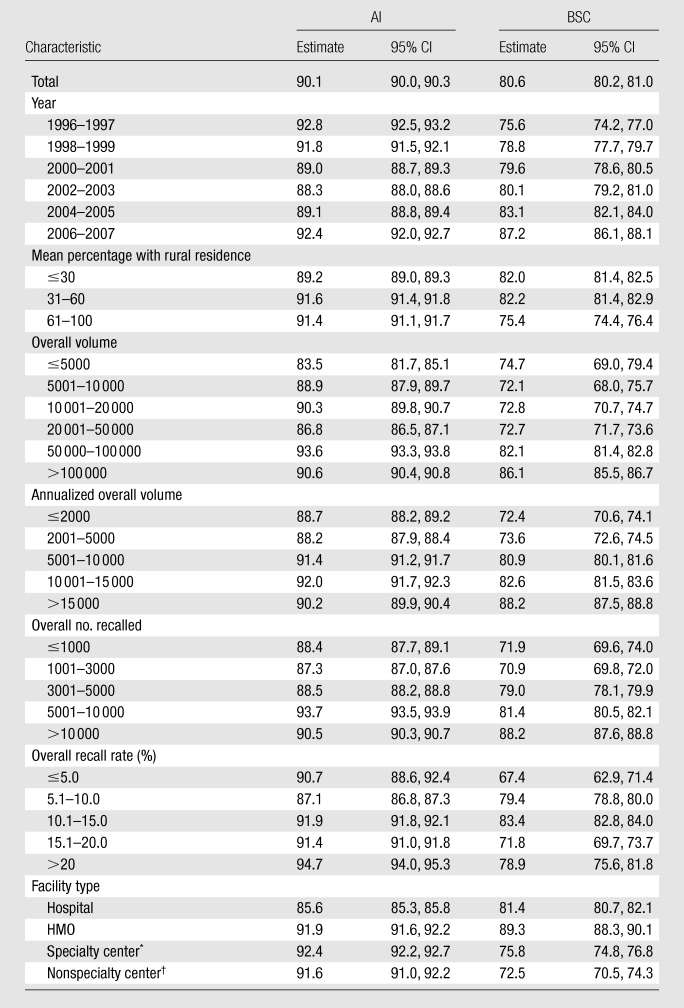

Table 4.

30-Day Follow-up Rates according to Type of Recommendation and across Facility-Level Characteristics among Women Who Returned within 180 Days

Note.—All data are percentages. CI = confidence interval.

Radiology private office or hospital outpatient center.

Obstetrics and gynecology office, primary care office, or multispecialty clinic.

The largest notable difference in percentage of follow-up at 15 or 30 days (Tables 3, 4) was for facilities with the smallest volume of mammograms (<5000 per year), with 10% fewer patients with follow-up at 15 days compared with the highest-volume facilities (P < .001).

For BSC, 15- and 30-day follow-up rates differed across several facility-level characteristics (Tables 3, 4). Facilities serving rural patients and small-volume facilities had notably lower follow-up rates at 15 days (P < .01), and notable (P < .01) differences persisted at 30 days. Facilities dominated by rural patients had 38% of surgical follow-up completed at 15 days, while practices with primarily urban patients had 56% of follow-up completed at that time. Smaller notable (P < .01) differences persisted at 30 days. HMO-associated facilities had the best performance for BSC at 15 and 30 days, with nonspecialty centers demonstrating the notably (P < .01) lowest rates at both 15 and 30 days.

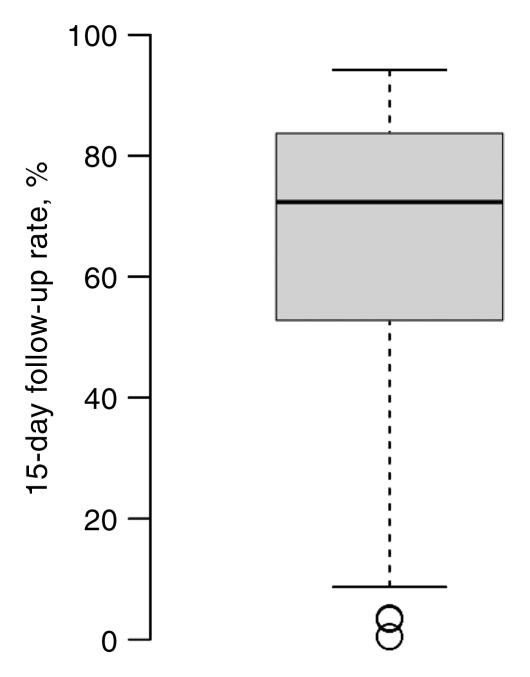

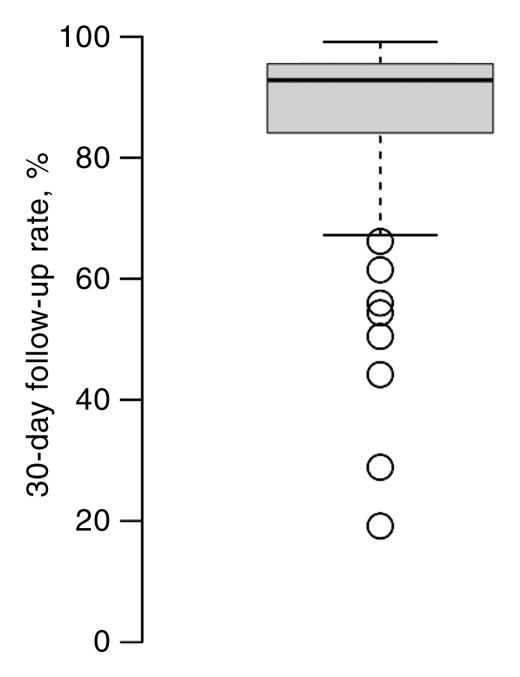

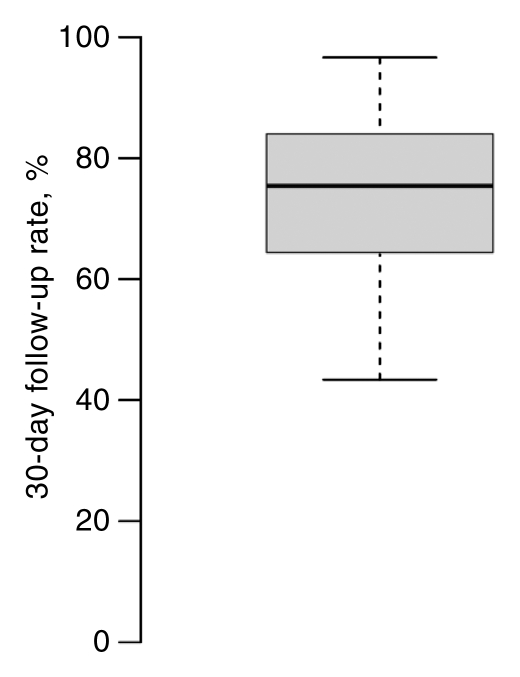

Facilities varied widely in percentage of completion of follow-up for both AI and BSC at 15 and 30 days (Fig 4). These between-facility differences are much larger than the differences seen among any of the facility characteristics (Tables 3, 4). The 15-day follow-up rates for the middle 50% of facilities varied between 50% and 80%; some facilities had very low follow-up rates, and some were nearly complete (Fig 4). For BSC, half of facilities had between 30% and 45% follow-up at 15 days. However, at 15 days some facilities were able to follow up almost 65% of cases, and others were able to follow up only 10% of cases.

Figure 4a:

Box plots of facility-specific follow-up rates stratified according to recommendation type: (a, b) AI, (c, d) BSC. Shaded area = 50% of facilities, central bar = mean, bars below and above boxes = 25% and 75% of facilities, ○ = outliers.

Figure 4b:

Box plots of facility-specific follow-up rates stratified according to recommendation type: (a, b) AI, (c, d) BSC. Shaded area = 50% of facilities, central bar = mean, bars below and above boxes = 25% and 75% of facilities, ○ = outliers.

Figure 4c:

Box plots of facility-specific follow-up rates stratified according to recommendation type: (a, b) AI, (c, d) BSC. Shaded area = 50% of facilities, central bar = mean, bars below and above boxes = 25% and 75% of facilities, ○ = outliers.

Figure 4d:

Box plots of facility-specific follow-up rates stratified according to recommendation type: (a, b) AI, (c, d) BSC. Shaded area = 50% of facilities, central bar = mean, bars below and above boxes = 25% and 75% of facilities, ○ = outliers.

Discussion

Because screening mammography involves multiple steps and sometimes multiple facilities, delays may occur in many places, and each facility needs procedures tailored to its circumstances. The 10% of screening studies requiring additional evaluation and especially the 2% requiring biopsy are key, as they contain the screening-detected cancers. An optimal screening system would minimize the time required to complete the screening process—and thus minimize patient anxiety. Also, while difficult to document, timely follow-up seems likely to maximize complete follow-up.

Overall, despite rapid initial follow-up of AI, variation between facilities is considerable and unexplained. The average delay of 14 days for an AI recommendation and 16 days for a BSC recommendation are not excessive from the standpoint of the biology of breast cancer, but many patients experience substantial delays that may be unacceptable emotionally. Some facility types—such as those that are “hospital based”—experience longer delays following AI, but most of the variations between facilities were not primarily associated with facility-level factors or the types of patients they service. One consistent characteristic associated with timely follow-up of both AI and BSC is larger mammography volumes. Many unknown factors undoubtedly contribute to observed differences. These would include differences in availability and handling of prior studies. A persistent concern is how these delays affect women’s satisfaction and use of subsequent screening, since most follow-up tests will not lead to a cancer diagnosis. Fortunately, on average, women with false-positive test results are more likely to return (25) for subsequent screening mammography.

Our findings of timeliness for BSC follow-up resemble those for AI but document longer times and more variation between facilities. Because BSC is less common than AI, it may be less readily available or unavailable at the same facility as the screening or AI examination. Urban-rural differences exist but are smaller than in a previous report from the New Mexico Mammography Project (14).

The improvement in timeliness between 1996 and 2007 follows a different pattern for BSC than for AI recommendations. For BSC, timeliness improved continuously, whereas for AI, timeliness was worse for the first few years and then recovered. These data alone suggest no reason for these trends; however, recent changes in biopsy procedures from surgical excision to core biopsy (26) offer a plausible explanation. Open-biopsy procedures with needle localization require coordination between radiology and surgery, substantially complicating and possibly delaying the process. Image-guided needle biopsy logistics are therefore likely to be simpler.

There are several primarily single-facility publications (5,8,13,14,16,27) in which timeliness of follow-up after a screening mammogram is reported by using a variety of methods and definitions. In these publications, the mean or median follow-up times for AI of 10–21 days and for BSC of 10–35 days are reported. The recommendations of the fourth edition of the European guidelines (2) are that women be notified and first offered follow-up by 20 working days for AI or BSC. This report encompasses many more follow-up studies, over a longer time, and from many more facilities. While differences in methods and definitions may limit comparison with data in other reports, the median times for AI and BSC follow-up are similar but generally better and may be related to a bias of those facilities reporting results and interventions. This report, focusing on more than 100 facilities, documents wide variation in community performance. While this large collection of facilities is a convenience sample, not a random sample, the locations of the facilities are diverse and should closely represent community practices.

There were several potential limitations in our study. We relied on observational data from facilities with different reporting systems. Because some patients had no known follow-up, they were excluded from the analysis, and some may have undergone follow-up at other facilities. In addition, patients with same-day follow-up were excluded. We did not capture the data with respect to follow-up rate according to facility type, and, clearly, these exclusions could have affected our results, and future work should determine the magnitude of these effects. The decision to exclude follow-up times beyond 180 days is justified, as longer follow-up times are clinically inappropriate. Finally, our analysis was limited to a narrow set of available facility variables that did not explain much of the observed variation among facilities.

In conclusion, time to follow-up varies widely between facilities, suggesting potential for improvement by many facilities, and takes longer for BSC recommendations than for AI recommendations. However, most patients undergo follow-up within the minimum standard recommendations of the European guidelines, so those guidelines may be a reasonable target within the United States. Finally, most follow-up that occurs is accomplished by 30 days for AI and slightly longer for BSC recommendations.

Advances in Knowledge.

In a large group of diverse facilities, the timeliness of follow-up care among women undergoing screening mammography, with a recommendation for immediate follow-up and who received follow-up care within 180 days, is described; women with a recommendation for additional imaging on the basis of findings on routine screening views had a median follow-up of 14 days.

Women with a recommendation for biopsy or surgical follow-up at the end of imaging work-up and within 90 days of the initial screening mammogram had a median follow-up of 16 days.

Approximately 90% of additional imaging and 81% of biopsies that were observed occurred within 30 days of the recommendation.

There was large variability according to facility in the timeliness of imaging follow-up, with some facilities achieving over 80% follow-up, and others less than 60%, within 15 days.

The timeliness of follow-up as measured in this report improved between 1996 and 2007: Among women with a recommendation for biopsy or surgical consultation, completion rate at 15 days increased from 39.2% to 62.0%.

Implications for Patient Care.

Most patients receive timely follow-up after an abnormal screening mammogram.

Many U.S. facilities within the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium reach the fourth edition of the European guidelines that any biopsy occur within 15 days of being offered; however, there is wide variation and room for improvement.

Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: R.D.R. Financial activities related to the present article: institution received grants, grant support for travel to meetings for the study or other purposes, and payment for writing or reviewing the manuscript from the National Cancer Institute and American Cancer Society. Financial activities not related to the present article: institution received grants from National Cancer Institute and American Cancer Society. Other relationships: none to disclose. S.J.P.A.H. Financial activities related to the present article: institution received a grant and support for travel to meetings for the study or other purposes from the National Cancer Institute. Financial activities not related to the present article: none to disclose. Other relationships: none to disclose. B.M.G. Financial activities related to the present article: institution received a grant and support for travel to meetings for the study or other purposes from National Cancer Institute. Financial activities not related to the present article: none to disclose. Other relationships: none to disclose. D.S.M.B. Financial activities related to the present article: institution received a grant and support for travel to meetings for the study or other purposes from the National Institutes of Health and American Cancer Society. Financial activities not related to the present article: none to disclose. Other relationships: none to disclose. D.L.M. Financial activities related to the present article: institution received grants from the National Cancer Institute–funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium cooperative agreement. Financial activities not related to the present article: institution has grants pending from the National Institutes of Health. Other relationships: none to disclose. R.J.B. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. R.S. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. S.H.T. Financial activities related to the present article: is an employee of the U.S. federal government through the National Cancer Institute. Financial activities not related to the present article: none to disclose. Other relationships: none to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating women, mammography facilities, and radiologists for the data they provided for this study. A list of the BCSC investigators and procedures for requesting BCSC data for research purposes are provided at http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/. The collection of cancer data used in this study was supported in part by several state public health departments and cancer registries throughout the United States. A full description of these sources is available at http://www.breastscreening.cancer.gov/work/acknowledgement.html.

Received December 29, 2010; revision requested February 8, 2011; final revision received April 12; accepted May 4; final version accepted June 14.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. federal government, the National Cancer Institute, or the National Institutes of Health.

Supported by the American Cancer Society (grant PA 8357).

Funding This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute–funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium cooperative agreement (grants U01CA63740, U01CA86076, U01CA86082, U01CA63736, U01CA70013, U01CA69976, U01CA63731, and U01CA70040). S.H.T. is an employee of the National Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations:

- AI

- additional imaging

- BCSC

- Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium

- BSC

- biopsy or surgical consultation

- HMO

- health maintenance organization

References

- 1.Rosenberg RD, Yankaskas BC, Abraham LA, et al. Performance benchmarks for screening mammography. Radiology 2006;241(1):55–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, Törnberg S, Holland R, von Karsa L. European Guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. 4th ed. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2006; 187, 188, 213 [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Consortium of Breast Centers Quality performance you should measure. National Quality Measures for Breast Centers. http://www.nqmbc.org/QualityPerformanceYouShouldMeasure.htm. Accessed May 8, 2010

- 4.Allen JD, Shelton RC, Harden E, Goldman RE. Follow-up of abnormal screening mammograms among low-income ethnically diverse women: findings from a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns 2008;72(2):283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnsberger P, Fox P, Ryder P, Nussey B, Zhang X, Otero-Sabogal R. Timely follow-up among multicultural women with abnormal mammograms. Am J Health Behav 2006;30(1):51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown ML, Houn F. Quality assurance audits of community screening mammography practices: availability of active follow-up for data collection and outcome assessment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1994;163(4):825–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang SW, Kerlikowske K, Nápoles-Springer A, Posner SF, Sickles EA, Pérez-Stable EJ. Racial differences in timeliness of follow-up after abnormal screening mammography. Cancer 1996;78(7):1395–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiarelli AM, Mai V, Halapy EE, Shumak RS, O’Malley FP, Klar NS. Effect of screening result on waiting times to assessment and breast cancer diagnosis: results from the Ontario Breast Screening Program. Can J Public Health 2005;96(4):259–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decker KM, Harrison M, Chateau D. Influence of direct referrals on time to diagnosis after an abnormal breast screening result. Cancer Detect Prev 2004;28(5):361–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrante JM, Chen PH, Kim S. The effect of patient navigation on time to diagnosis, anxiety, and satisfaction in urban minority women with abnormal mammograms: a randomized controlled trial. J Urban Health 2008;85(1):114–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrante JM, Rovi S, Das K, Kim S. Family physicians expedite diagnosis of breast disease in urban minority women. J Am Board Fam Med 2007;20(1):52–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerlikowske K. Timeliness of follow-up after abnormal screening mammography. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1996;40(1):53–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Press R, Carrasquillo O, Sciacca RR, Giardina EG. Racial/ethnic disparities in time to follow-up after an abnormal mammogram. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(6):923–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yabroff KR, Ashbeck E, Rosenberg R. Trends in time to completion of mammographic screening and follow-up services. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;188(1):242–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zapka J, Taplin SH, Price RA, Cranos C, Yabroff R. Factors in quality care: the case of follow-up to abnormal cancer screening tests—problems in the steps and interfaces of care. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2010;2010(40):58–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams SA, Smith ER, Hardin J, Prabhu-Das I, Fulton J, Hebert JR. Racial differences in follow-up of abnormal mammography findings among economically disadvantaged women. Cancer 2009;115(24):5788–5797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ballard-Barbash R, Taplin SH, Yankaskas BC, et al. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: a national mammography screening and outcomes database. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997;169(4):1001–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium BCSC glossary of terms. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium Web site. http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/data/bcsc_data_definitions.pdf. Updated September 16, 2009. Accessed August 16, 2011.

- 19.Yankaskas BC, Taplin SH, Ichikawa L, et al. Association between mammography timing and measures of screening performance in the United States. Radiology 2005;234(2):363–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geller BM, Ichikawa LE, Buist DS, et al. Improving the concordance of mammography assessment and management recommendations. Radiology 2006;241(1):67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taplin SH, Ichikawa LE, Kerlikowske K, et al. Concordance of Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System assessments and management recommendations in screening mammography. Radiology 2002;222(2):529–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldman LE, Haneuse SJ, Miglioretti DL, et al. An assessment of the quality of mammography care at facilities treating medically vulnerable populations. Med Care 2008;46(7):701–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium Search BCSC publications. http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/publications/search.html. Published 2010. Accessed March 7, 2011

- 24.MQSA certified mammography facilities and accredited mammography units ACR Mammography Accreditation Program American College of Radiology Web site. http://www.acr.org/accreditation/mammography/overview/mammo_unit_chart.aspx. Accessed 2010

- 25.Brewer NTST, Salz T, Lillie SE. Systematic review: the long-term effects of false-positive mammograms. Ann Intern Med 2007;146(7):502–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwan SW, Bhargavan M, Kerlan RKJ, Jr, Sunshine JH. Effect of advanced imaging technology on how biopsies are done and who does them. Radiology 2010;256(3):751–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardenosa G, Eklund GW. Rate of compliance with recommendations for additional mammographic views and biopsies. Radiology 1991;181(2):359–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]