Abstract

A 29-year-old pregnant woman with parity 0-0-0-0 was diagnosed with monoamniotic twin pregnancy discordant for anencephaly at 14 weeks gestation. Umbilical cord entanglement, which is an important cause of fetal death in monoamniotic twins, was confirmed by three-dimensional ultrasound. Cesarean section was performed at 34 weeks of gestation, and the normal newborn infant was discharged without any complications. We report a case of monoamniotic twin pregnancy discordant for anencephaly and diagnosed with cord entanglement by three-dimensional ultrasound at 14 weeks of gestation, and now report it along with a literature review.

Keywords: monoamniotc twin, anencephaly, cord entanglement, 3D

Introduction

A monoamniotic twin pregnancy, in which 2 fetuses coexist within one amnion, occurs during cleavage between 8 and 13 days after fertilization. The prevalence of monoamniotic twins is estimated to be between 1 in 5000 and 1 in 25,000 pregnancies. Perinatal mortality of monoamniotic twins is high, ranging between 8-42% of these pregnancies, due to prematurity, umbilical cord entanglement, twin to twin transfusion syndrome, congenital anomalies, and intrauterine growth restriction. In particular, umbilical cord entanglement was reported to be found in up to 100% of monoamniotic twins 1. As umbilical cord entanglement leads to a > 50% of fetal death rate, its accurate diagnosis and active treatments are very critical 2. Monoamniotic twin pregnancy discordant for anencephaly is a rare occurrence with only 11 prior reported cases.

We experienced a case of successful delivery at 34 weeks of pregnancy through fetal monitoring using Doppler ultrasound after umbilical cord entanglement was observed in monoamniotic twin pregnancy associated with one fetus with anencephaly by using three dimensional (3D) ultrasound at 14 weeks, and now reports it along with literature review.

Case Report

A 29-year-old pregnant woman with parity 0-0-0-0 visited the hospital at 14 weeks after spontaneous pregnancy. Abdominal 2D ultrasound (Voluson E8, GE Healthcare, USA) revealed that the first twin was within the normal ranges for the gestational age but the second twin showed anencephaly. There was one placenta and no amniotic membrane separated the two fetuses, and both were male. Umbilical cord entanglement was observed by using 3D ultrasound (Voluson E8, GE Healthcare, USA) (Fig. 1). The parents received counseling regarding monoamniotic twin pregnancy, anencephaly of a fetus and complications of umbilical cord entanglement. The patient underwent weekly prenatal medical examinations at the outpatient clinic. A fetal ultrasound conducted at 22 weeks did not show any abnormal finding except for one fetal anencephaly (Fig. 2). Starting from 26 weeks, a Doppler study of the umbilical cord and a non-stress test were performed every week and their results were within normal ranges. Also, amniotic fluid index (AFI) was checked every week, polyhydramnios (AFI = 25) was detected at 26 weeks and persisted until delivery (AFI: 20 ~ 28). The polyhydramnios was asymptomatic and was not treated. Although hospitalization for intensive observation was recommended at 30 weeks of pregnancy, the patient refused such treatment. While she was examined as an outpatient, preterm labor occurred at 33+5 weeks and she was subsequently hospitalized.

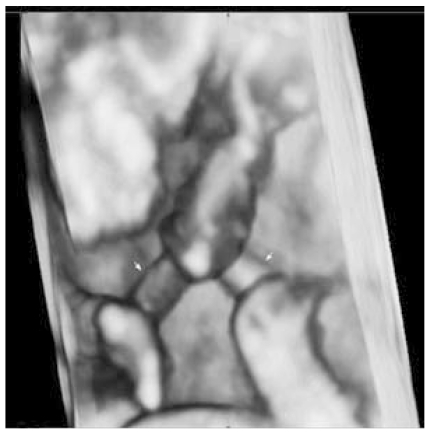

Fig 1.

A three-dimensional ultrasound image demonstrates that each fetal umbilical cord (arrow) is entangled at 14weeks of gestation.

Fig 2.

A three-dimensional ultrasound image demonstrates that the normal fetus put his arms around the shoulders of the other fetus with anencephaly and leaned against him at 22 weeks of gestation.

A single course of steroids for lung maturation were given immediately after hospitalization. The heartbeat of the 2 fetuses were 140 beats/min and 130 beats/min, respectively and showed normal variability, and 20~30 mmHg uterine contractions were observed every 3 minutes. At 34 weeks a Cesarean section was performed under general anesthesia. The first male infant had a weight of 2,210 g, and his Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes were 6 and 8, respectively. No gross abnormalities were observed. The second infant weighted 1,380 g and his Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes were 1 and 0, respectively. Other than anencephaly, no gross abnormalities were observed in the second twin. The first twin was moved to the neonatal intensive care unit immediately after Cesarean section and was cared for without intratracheal intubation or use of a ventilator. He was discharged without any complications on the fifth day after birth and the mother was also discharged without any unusual findings on the same day.

The gross findings for the umbilical cord were very similar to that of umbilical cord entanglement observed through 3D ultrasound at 14 weeks (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

The gross findings of entanglement of the cord was very similar to that of umbilical cord entanglement observed through 3D ultrasound at 14 weeks.

Discussion

Monoamniotic twin pregnancies can be diagnosed most accurately when one yolk sac with 2 embryos or fetuses is found on the ultrasound image during the first trimester of pregnancy. After this period, they are diagnosed through ultrasound when no amnion is present between twins with a single placenta and their gender is the same 2.

Most studies on monoamniotic twins have addressed perinatal mortality and how to reduce it. Perinatal mortality was reported to be 28-47% and 32% by Lumme and Saarikoski, and Demaria et al., respectively 3, 4. This high mortality was known to be caused by prematurity, twin to twin transfusion syndrome, congenital anomalies, intrauterine growth restriction, and umbilical cord entanglement 5, 6. The occurrence of monoamniotic twin pregnancy discordant for anencephaly could be estimated as 1: 500 million live births 7. In the literature, we found 11 cases of monoamniotic twins in which there was anencephaly in at least one of the fetuses. Of those, 10 cases had good outcomes in that a normal infant was discharged from the hospital in good condition. Two types of specific problems can be suggested for monoamniotic twin pregnancy discordant for anencephaly. One is abrupt, uncoordinated movement of the anencephalic fetus can cause further stretching and compression of the umbilical cords that lead to fetal death of the structurally normal twin 8. Another problem is associated with polyhydramnios caused by impairment of the swallowing reflex of the anencephaly fetus. Management of these cases may be a dilemma to most obstetricians. Aggressive management is selective termination of the anencephaly twin and transaction of its umbilical cords for preventing intrauterine death of the structurally normal twin 8. However, this management is difficult to accept in countries where pregnancy termination is not allowed, even though demise of the structurally normal twin can be a result of the fetus with the lethal anomaly. Additionally, invasive management has potential complications, including rupture of membranes and requires high levels of skill for the physician.

In case of conservative treatment, preterm delivery at ~ 32 weeks of gestation 7, when risks of prematurity are burdened, can be the choice for preventing death of the normal twin. In our case, conservative management was undertaken and the result was successful.

Umbilical cord entanglement was long considered to be the only cause of death in monoamniotic pregnancies. However, according to a recent study, umbilical cord entanglement was found in all monoamniotic twins 1 and it was hard to say that umbilical cord entanglement itself was the unique cause of death 9. Because 2 freely moving fetuses exist in the same space for 9 months, umbilical cord entanglement is inevitable and an expected complication.

However, obstetricians dealing with monoamniotic twins should diagnose umbilical cord entanglement prenatally, and when cord entanglement is observed, they should monitor fetuses to investigate signs of compression or occlusion of the umbilical cord. Antenatal monitoring is aimed at preventing fetal death. We think that the best time to start monitoring is at 25-26 weeks of gestation, when fetal viability is reached.

Although umbilical cord entanglement has been previously diagnosed with 2D ultrasound, it was difficult to confirm umbilical cord entanglement. Sherer et al. reported that they found umbilical cord entanglement on the transvaginal 2D color Doppler sonogram at 12 weeks' gestation 10. However, it was difficult for the patient and her family to understand and accept that umbilical cord entanglement had occurred. Although the diagnosis can be made with 2D Doppler, 3D images provide clearer visualization of the cord entanglement and can help illustrate the problem to the parents. The cases using 3D images have been rarely reported and most 3D ultrasounds are conducted in the third trimester of pregnancy 11-13. Yet, to date, our case is the first to diagnose umbilical cord entanglement by using 3D ultrasound at the first trimester. After delivery, the shape of umbilical cord entanglement was the same as that seen in the 3D ultrasound image. This finding supported a hypothesis that umbilical cord entanglement of monoamniotic twins occurred from the first trimester of pregnancy when the amount of amniotic fluid was relatively large compared to the size of the fetuses and they actively moved 14.

Our case revealed entanglement of umbilical cords with 3D ultrasound at 14 weeks of gestation and in a monoamniotic twin pregnancy associated with one fetal anencephaly, and may help in providing successful outcomes.

References

- 1.Dias T, Mahsud-Dornan S, Bhide A, Papageorghiou AT, Thilaganathan B. Cord entanglement and perinatal outcome in monoamniotic twin pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35:201–4. doi: 10.1002/uog.7501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasquini L, Wimalasundera RC, Fisk NM. Management of other complications specific to monochorionic twin pregnancies. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18:577–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lumme RH, Saarikoski SV. Monoamniotic twin pregnancy. Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma) 1986;35:99–105. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000006309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demaria F, Goffinet F, Kayem G, Tsatsaris V, Hessabi M, Cabrol D. Monoamniotic twin pregnancies: antenatal management and perinatal results of 19 consecutive cases. BJOG. 2004;111:22–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen VM, Windrim R, Barrett J, Ohlsson A. Management of monoamniotic twin pregnancies: A case series and systematic review of the literature. BJOG. 2001;108:931–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roqué H, Gillen-Goldstein J, Funai E, Young BK, Lockwood CJ. Perinatal outcomes in monoamniotic gestations. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003;13:414–21. doi: 10.1080/jmf.13.6.414.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim KI, Dy C, Pugash D, Williams KP. Monoamniotic twins discordant for anencephaly managed conservatively with good outcomes: Two case reports and a review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26:188–93. doi: 10.1002/uog.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sepulveda W, Wong AE, Sandoval R, Aiello H, Otaño L. Monoamniotic twin pregnancy discordant for lethal open cranial defect: Management dilemmas. Prenat Diagn. 2011;31:578–82. doi: 10.1002/pd.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasquini L, Wimalasundera RC, Fichera A, Barigye O, Chappell L, Fisk NM. High perinatal survival in monoamniotic twins managed by prophylactic sulindac, intensive ultrasound surveillance, and cesarean delivery at 32 weeks' gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;28:681–7. doi: 10.1002/uog.3811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherer DM, Sokolovski M, Haratz-Rubinstein N. Diagnosis of umbilical cord entanglement of monoamniotic twins by first-trimester color doppler imaging. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:1307–9. doi: 10.7863/jum.2002.21.11.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuwata T, Matsubara S, Suzuki M. 3D color Doppler of monoamniotic twin cord entanglement. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281:973–4. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vayssière C, Plumeré C, Gasser B, Neumann M, Favre R, Nisand I. Diagnosing umbilical cord entanglement in monoamniotic twins: Becoming easier and probably essential. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:587–9. doi: 10.1002/uog.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henrich W, Tutschek B. Cord entanglement in monoamniotic twins: 2D and 3D colour doppler studies. Ultraschall Med. 2008;29(Suppl 5):271–2. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-963641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overton TG, Denbow ML, Duncan KR, Fisk NM. First-trimester cord entanglement in monoamniotic twins. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;13:140–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.13020140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]