Abstract

Biofuels developed from biomass crops have the potential to supply a significant portion of our transportation fuel needs. To achieve this potential, however, it will be necessary to develop improved plant germplasm specifically tailored to serve as energy crops. Liquid transportation fuel can be created from the sugars locked inside plant cell walls. Unfortunately, these sugars are inherently resistant to hydrolytic release because they are contained in polysaccharides embedded in lignin. Overcoming this obstacle is a major objective toward developing sustainable bioenergy crop plants. The maize Corngrass1 (Cg1) gene encodes a microRNA that promotes juvenile cell wall identities and morphology. To test the hypothesis that juvenile biomass has superior qualities as a potential biofuel feedstock, the Cg1 gene was transferred into several other plants, including the bioenergy crop Panicum virgatum (switchgrass). Such plants were found to have up to 250% more starch, resulting in higher glucose release from saccharification assays with or without biomass pretreatment. In addition, a complete inhibition of flowering was observed in both greenhouse and field grown plants. These results point to the potential utility of this approach, both for the domestication of new biofuel crops, and for the limitation of transgene flow into native plant species.

Plant biomass can be broken down to monosaccharides (saccharification) and converted to fuels. Plant cell walls are composed of cellulose microfibrils embedded in a cross-linked network of matrix polysaccharides and copolymerized with lignin. This complex structure inhibits the saccharification of cell wall polysaccharides by cell wall degrading enzymes. Furthermore, byproducts of the harsh pretreatments necessary to enable saccharification inhibit growth of microorganisms used to produce biofuels. Therefore, improving saccharification efficiency is one of the major goals in developing an efficient, cost-effective biofuel industry (1). Because a wealth of genetic and molecular resources exists for maize, it is well suited as a model system for the identification of genes important for biomass accumulation and saccharification in grasses (2).

Plants go through a series of development stages over time in response to a variety of stimuli, both external and internal. Each phase displays unique morphological and physiological characteristics that change when the plant undergoes a transition to the next phase. One such developmental transition is the switch from the juvenile to adult phase of development (3). In general, juvenile plant material is less lignified and displays differences in biomass accumulation and character. These juvenile traits may reduce the recalcitrance of biomass to conversion into fermentable sugars. By controlling the genes that regulate the juvenile to adult phase transition in plants, it may be possible to modify or enhance the biomass properties of a wide range of bioenergy feedstocks.

The dominant maize Corngrass1 (Cg1) mutant fixes plant development in the juvenile phase and affects both biomass accumulation and saccharification efficiency. Cg1 mutants increase biomass due to continuous initiation of axillary branches (tillers) and leaves (4). The resulting biomass has reduced adult characteristics and ectopic juvenile cell identities (5). In addition, Cg1 mutant leaves contain decreased amounts of lignin and increased levels of glucose and other sugars compared with wild type (6), which could provide an improved substrate for saccharification.

We cloned Cg1 and showed that it is an unusual grass-specific tandem microRNA gene that is overexpressed in the mutant (7). This microRNA belongs to the miR156 class that is known to target the SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING LIKE (SPL) family of transcription factors (8). Overexpression of miR156 causes inappropriate cleavage of its targets, demonstrating that the Cg1 mutant phenotype is caused by loss of function of several SPL target genes (7). miR156 is temporally regulated, occurring at high levels during the juvenile phase and gradually disappearing during the adult phase in Arabidopsis and maize (7, 9). Overexpression of miR156 in Arabidopsis and rice results in phenotypes similar to Cg1 (10, 11), indicating functional conservation of this microRNA across a wide range of plant species.

SPL genes have a variety of functions, including control of male fertility (12), copper metabolism (13), plastochron time (14, 15), bract suppression (16), and flowering time (17, 18). Recently, it has been shown that SPL genes directly target and activate expression of flowering regulators such as LEAFY and APETALA1 (19), and a different microRNA, miR172 (17). Expression of miR172 during the adult phase of development promotes flowering by repressing floral repressors such as the SMZ and SNZ genes (20, 21). Thus, the miR156-targeted SPL genes have a positive effect on the floral transition through multiple independent pathways. Consistent with these findings, the Cg1 mutant in maize is slow to flower and has greatly reduced numbers of floral and inflorescence meristems (7).

Because members of the miR156 targeted SPL gene family are conserved in different plant species, it is feasible to transfer the desired biofuel processing properties of Cg1 into any crop of choice simply by overexpressing the Cg1 cDNA. Here we test this hypothesis by constitutively expressing Cg1 in the monocots, Brachypodium distachyon (Brachypodium), Panicum virgatum (switchgrass), and a dicot, Arabidopsis. We show that it is possible to affect biomass composition, digestibility, and flowering through genetic manipulation of miR156 and its targets.

Results

Cg1 Overexpression Promotes Juvenile Leaf Traits.

The full-length maize Cg1 cDNA was expressed behind the 35S promoter in Arabidopsis or behind the maize UBIQUITIN (UBI) promoter (22) in Brachypodium and switchgrass using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Similar to the maize Cg1 mutant (Fig. 1A), Arabidopsis 35S::Cg1 transformants (Fig. 1B) displayed increased vegetative branching and increased leaf initiation in line with earlier reports of miR156 overexpression (10). These plants flowered approximately 2 to 3 wk later and had morphologically normal flowers (Fig. 1B). UBI::Cg1 transformants in Brachypodium displayed a similar increase in leaf production, branching, and delayed flowering time (Fig. 1C), but also produced inflorescences with fewer spikelets (Fig. 1C, Inset). The same construct was put into switchgrass with similar results (Fig. 1D), except that the plants never flowered. In general, leaves in all species expressing Cg1 were narrow and more numerous compared with wild-type adult leaves.

Fig. 1.

Overexpression of Cg1 in different plant species. (A) Cg1 overexpression in maize (Left) compared with wild-type sibling (Right). (B) Cg1 overexpression in Arabidopsis (Left) compared with wild-type Columbia (Right). (C) Cg1 overexpression in Brachypodium (Left) compared with wild-type Bd21-3 (Right). Inset shows inflorescence morphology. (D) Cg1 overexpression in switchgrass (Left) compared with wild-type Alamo (Right). All plants are the same age and grown under the same conditions.

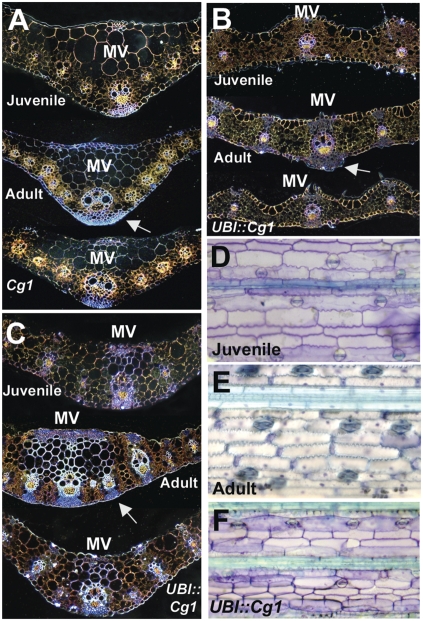

Plastic sections of Cg1 overexpressing leaves of grass species revealed numerous differences in cell number, morphology, and identity (Fig. 2 A–C). In general, Cg1 overexpressing leaves in maize, switchgrass, and Brachypodium had fewer cell layers, reduced leaf thickness, and fewer hypodermal sclerenchyma cells (lignified support cells) (arrows) compared with wild-type adult leaves of similar age. Epidermal peels of leaves were performed on switchgrass to determine whether the transformants had juvenile cell identity. In maize, wild-type juvenile waxes stain purple with Toluidine Blue (TBO), whereas adult waxes stain aqua (23), and the same is true in switchgrass (Fig. 2 D and E). All leaves of the Cg1 overexpressors displayed juvenile waxes on the basis of TBO staining (Fig. 2F). In addition, epidermal cells were less crenulated and had thinner walls compared with wild type (Fig. 2F). Cg1 overexpressers in both maize and switchgrass also showed increased juvenile biochemical properties such as an increase in the juvenile and grass-specific, cell wall (1,3;1,4)-β-d-glucans (Fig. S1) (24). In summary, the leaves of all species that overexpress Cg1 had both juvenile morphology and cell identities relative to nontransgenic plants, consistent with the maize Cg1 phenotype.

Fig. 2.

Histological analysis of Cg1 overexpressors. (A) Plastic sections of juvenile, adult, and Cg1 leaves of maize. (B) Plastic sections of juvenile, adult, and UBI::Cg1 leaves of Brachypodium. (C) Plastic sections of juvenile, adult, and UBI::Cg1 leaves of switchgrass. (D) Epidermal peel of juvenile switchgrass leaf. (E) Epidermal peel of adult switchgrass leaf. (F) Epidermal peel of UBI::Cg1 switchgrass leaf. All plastic sections and epidermal peels were stained with Toluidine Blue. Arrows point to lignified hypodermal sclerenchyma cells.

Morphological and Molecular Analysis of Ubi:Cg1 Switchgrass.

To fully understand the impact of the Cg1 mutants on the phenotype and composition of switchgrass, 20 independent UBI::Cg1 switchgrass transformants were generated and sorted into three phenotypic classes (severe, moderate, and weak) (Fig. 3A) on the basis of phenotypic severity and expression levels of the transgene (Fig. S2). In general, increasing levels of Cg1 expression were correlated with increasing phenotypic severity. Each class displayed increased vegetative branching, but also possessed unique phenotypes. High transgene expressers were severely dwarfed and had thinner stems with many small needle-like leaves. Moderate expressers had bigger leaves, thicker stems, and were less dwarfed. Both severe and moderate expressers produced long horizontally growing branches that initiated several aerial shoots with roots at each node (Fig. 3B), each capable of producing new plants. The leaves of the low-expressing weak class resembled wild type, except that they were narrower and had juvenile cell identity. In addition, the weak expressers only produced excess branches at nodes located at soil level.

Fig. 3.

Morphological and molecular analysis of UBI::Cg1 switchgrass plants. (A) Phenotypes of three classes of Cg1 switchgrass transformants. (B) Close up of a severe transformant showing ectopic shoots at each node. (C) Comparison of weakly expressing transformant (Left) and wild type (Right) in the field. Wild-type plant is flowering. (D) Same plants in C, 3 wk postharvest. The transformant displays better recovery. (E) Comparison of first year postharvest dry weights of above-ground biomass of wild type and three classes of transformants. (F) Comparison of tiller numbers of wild type and three classes of transformants. For data in E and F error bars show 1 SE. Sample sizes: WT, n = 4; weak, n = 4; moderate, n = 6; and severe, n = 7. Asterisks indicate significant differences with wild type (Materials and Methods). (G) qPCR analysis of wild type and three classes of transformants using primers corresponding to four different miR156-targeted SPL genes. (H) qPCR analysis using primers corresponding to three different AP1 MADS box genes. (I) qPCR analysis using primers corresponding to a switchgrass glossy15 homolog.

The growth rate of each clone was assessed over the summer in the field (details in Materials and Methods). Transformants from the severe class with high levels of transgene expression displayed very limited growth and often died, whereas the low expressers generally kept pace with wild-type controls (Fig. 3C). None of the transformants ever flowered, even after more than a year in the field (two summers and one winter) or after 2 y in the greenhouse under long day conditions. In contrast, transformants overexpressing a miR156 target mimic construct, designed to inhibit miR156 activity (25), flowered normally.

At the end of the growing season, all of the above ground biomass was harvested, dried, and weighed. Postharvest, the weakly expressing class displayed better regenerative capacity, with each cut shoot forming a new tiller. In contrast, wild-type plants only regenerated new shoots from the periphery of the plant (Fig. 3D). A count of the total number of primary branches postharvest revealed that the weak-expressing class produced four times more branches, whereas the moderate and severe classes had only two to three times more, respectively (Fig. 3F). The average weight of the moderate and severe classes was significantly lower than wild type, but the weak class was not significantly lower (Fig. 3E). These results indicate that high levels of Cg1 expression are detrimental to plant growth and biomass accumulation, whereas weak expression can be tolerated.

To confirm that overexpression of Cg1 in switchgrass reduces SPL gene expression, qRT-PCR was performed using oligos corresponding to several switchgrass SPL homologs (Fig. 3G). As expected, the expression levels of four miR156-targeted SPL genes were down by several orders of magnitude in all transformants, the most dramatic found in the moderate and severe classes. Because SPL genes are known activators of AP1 MADS box genes necessary for specifying floral meristem identity (19, 26), the expression of three switchgrass homologs of AP1 was also assayed (Fig. 3H). Two of these genes, FL779848 and FL813474, were down-regulated in all transformants, whereas the third one, FL799727, showed no significant change. Assuming that FL779848 and FL813474 function similarly to AP1, the loss of these genes could explain the lack of flowering in the transformants. Because SPL genes are also known activators of miR172, it was predicted that targets of miR172 would show a converse expression pattern to the SPLs, and therefore be up-regulated in the transformants. This prediction was confirmed in the weakly expressing class with a putative switchgrass homolog of the maize glossy15 gene, FL805250, which functions to repress adult leaf cell characteristics (27) (Fig. 3I). The ectopic expression of this gene may help explain the extended juvenile leaf cell characteristics of the Cg1 transformants in switchgrass, maize, and Brachypodium.

Biochemical Properties of Ubi:Cg1 Plants.

Composition analysis of dried UBI::Cg1 switchgrass material was carried out to assess its amenability to biofuel production. Total lignin content of dried whole plants was measured using acetyl bromide assays (28) and showed modest reduction in all three classes of transformants (Fig. S3A), compared with both wild type and miR156 target mimic transformants used as a negative control. This finding is consistent with earlier lignin measurements of Cg1 leaves in maize (6). Cellulose levels and the amount of cellulose relative to lignin (Fig. S3 B and C) showed a modest increase in all three classes. In addition, two-step sulfuric acid hydrolysis followed by high-performance anion exchange chromatography (HPAEC) was used to measure monosaccharide levels (Fig. S3D) and revealed that each class of transformants had slightly higher glucan levels and lower xylan levels. These biochemical differences in biomass properties, although slight and significant only in the moderate class, indicated that these plants might be more easily saccharified.

Ubi:Cg1 Plants Store Starch in Their Stem.

Pretreatment of plant biomass is often used to make it more accessible to enzyme breakdown and fermentation. Saccharification assays using dilute alkali pretreatment demonstrated significantly higher glucose release in the severe switchgrass transformants (Fig. 4A) compared with maize, Brachypodium, and Arabidopsis Cg1 plants (Fig. S4). By contrast, saccharification assays on Cg1 switchgrass stems and leaves performed using acid pretreatment showed no significant difference in total glucose release over time in the transformants compared with wild type (Fig. S5). These differences suggest that some fermentable biomass components might be made accessible only by specific pretreatment regimes. Because the switchgrass plants never flower, we hypothesized that this difference might be due to alterations in stored carbohydrates, because many nonflowering Arabidopsis mutants display higher starch levels (29). Indeed, potassium iodide-stained hand sections of field grown leaves and stems demonstrated a striking difference in starch levels in stem segments of Cg1 switchgrass plants compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 4B). In postflowering wild-type switchgrass, starch is normally found in the lowermost nodes, whereas in Cg1 lines it is present in every node (Figs. S6 and S7). High levels of starch accumulation were not observed in maize, Brachypodium, and Arabidopsis Cg1 lines using the same potassium iodide assay.

Fig. 4.

Biofuel properties and digestibility of UBI::Cg1 switchgrass. (A) Saccharification assay using dilute base pretreatment of field grown leaves of wild type and three classes of transformants. Asterisks indicate significant differences with wild type. (B) Potassium iodide staining of upper nodes of field grown stems of Cg1 (Left) and wild type (Right). (C) Starch measurements of field grown stems of wild type and two independent transformants of each class. The severe class contained leaf bases. (D) Saccharification assay of stems and leaves of wild type and two independent weak transformants without biomass pretreatment after 24 h of digestion. Method I was done with Accelerase enzyme mixture, and method II was done with the same mixture plus α-amylase and amyloglucosidase. (E) Saccharification assay over 72 h of stems of two field grown wild-type plants and two weakly expressing transformants using method I without pretreatment. (F) Saccharification assay over 72 h of stems of two field grown wild-type plants and two weakly expressing transformants using method II without pretreatment. All transformants in D–F were assayed in duplicate.

Starch levels were measured directly from the stems of field grown transformants harvested before dawn. The weakly expressing transformants had >250% more starch in the stem, whereas the moderately expressing transformants had up to 189% more (Fig. 4C). The severe class had low starch presumably due to the fact that the tissue was a mixture of stem and leaf. Because the weak class of transformants appeared to grow at near normal rates compared with wild type in the field, they were chosen for further in depth analysis.

Additional saccharification assays of the weakly expressing transformants were performed without biomass pretreatment. Because the weak-expressing class had more starch, α-amylase and amyloglucosidase were either added to the saccharification enzyme mix to digest it (method II) or not (method I). Using method I, only a modest increase in glucose release was seen (Fig. 4D). However, three to four times more glucose was released from stems using method II after 24 h (Fig. 4D). The increase in glucose release from these transformants also displayed improved kinetics when measured over 72 h (Fig. 4 E and F). In fact, the amount of glucose release over time from weakly expressing stems using method II without pretreatment is similar to the amount derived from the same stems pretreated with dilute acid (Fig. S5). This finding indicates that Cg1 overexpression may either reduce or negate the pretreatment requirement for saccharification. Thus, weak Cg1 overexpression appears to transform the stem into a starch-containing storage organ, allowing for significantly higher glucose release in saccharification assays without pretreatment and without severely compromising plant growth.

Discussion

The maize Cg1 gene was overexpressed in several plants to fix them in the juvenile phase of development and determine its impact in the context of biofuel production. Cg1 is a unique tandem miR156 microRNA gene that, to date, has been identified only in grass species (7) and may have been under purifying selection during domestication (30). The unique structure of this gene may play a role in transcript stability because the full-length Cg1 transcript can be easily detected on RNA blots (7) in contrast to many miR156 precursors. In addition, overexpression of Cg1 causes a slightly different suite of phenotypes compared with simple miR156 overexpression in Arabidopsis (10). Because miR156 genes are highly conserved and have been identified in all sequenced plant genomes to date, it is feasible to fix any plant of choice in the juvenile phase simply by overexpressing the Cg1 cDNA. Cg1 overexpression in maize, Arabidopsis, Brachypodium, and switchgrass produced plants with extra branches and leaves that possess juvenile morphology, cell identity, and biochemical properties, confirming that high levels of miR156 are sufficient to induce juvenile development. Previous analysis of juvenile biomass in maize showed that it possessed decreased lignin and increased levels of certain sugars (6), making it a superior substrate for fermentation.

The Departments of Energy and Agriculture have identified switchgrass as a potential bioenergy crop that may reduce our reliance on fossil fuels (31). Ethanol produced from switchgrass biomass is projected to produce more than 500% more renewable energy than the energy consumed on the basis of lifecycle analysis and would emit 94% fewer greenhouse gases than gasoline (32). Switchgrass is a warm season C4 perennial grass with no vernalization requirement and can flower under long days followed by short days (33, 34). It can flourish on marginal cropland, does not compete with food crops, and requires minimal growth inputs. Taking into consideration the ecological impacts such as soil conservation, improvement in water quality, wildlife habitat restoration, and reduction in carbon emissions (35), it is clear that switchgrass has numerous potential environmental benefits in addition to its economic ones. Using transgenic technology to improve the biofuel properties of this plant is a feasible way to quickly establish it as a viable bioenergy crop at a commercial scale in the United States and the world. Here, we tested the hypothesis that juvenile biomass of switchgrass could represent an enhanced feedstock for the biofuel industry.

We show that Cg1 switchgrass tissue is easier to digest and releases more glucose in saccharification assays of specific tissues using either alkaline pretreatment (Fig. 4A) or no pretreatment (Fig. 4 D–F). The ability to release glucose in the absence of pretreatment is due to the presence of starch in stems that is only fully released through addition of starch degrading enzymes to the saccharification mix. Thus, juvenile biomass has unique properties, both histologically and biochemically, which together make it an attractive target for modification to improve biofuel production. It is clear, however, that high levels of ubiquitous Cg1 expression have detrimental effects on overall plant growth (Fig. 3E). To address these problems, constructs driving Cg1 behind weakly expressing tissue-specific promoters are pending.

An unexpected consequence of Cg1 overexpression in switchgrass was the absence of flowering in both the greenhouse and the field, even after more than 2 y of growth. Lack of flowering was not seen in any other plants overexpressing miR156, including maize, Arabidopsis, and rice (4, 10, 11) and could reflect a novel role for SPL genes in controlling flowering in switchgrass. Several flowering time genes have been identified and analyzed in monocots, including CONSTANS, EARLY HEADING DATE, HEADING DATE 3A, and INDETERMINATE (36). None of these genes, however, showed any significant expression difference in the switchgrass transformants compared with wild type. The SPL transcription factors regulated by miR156 are known regulators of AP1 MADS box transcription factors (19). In fact, the first SPL gene was cloned on the basis of its ability to bind the promoter of the AP1 ortholog in Antirrhinum (26). The AP1 gene is a regulator of floral meristem identity and is the last step in the Arabidopsis flowering pathway (37). Two of three switchgrass AP1 homologs were greatly reduced in expression in the Cg1 transformants, and a reasonable hypothesis is that several of these AP1 genes are required for floral initiation in switchgrass. Alternatively, the switchgrass plants may not flower as a consequence of increased expression from AP2 gene targets of miR172, which function as floral repressors (21). Overexpression of miR156 is known to repress miR172 in grasses (7), causing targets of miR172 to be up-regulated. In support of this observation, a switchgrass homolog of the miR172 AP2 target gene glossy15 is up-regulated in the Cg1 weakly expressing lines, making it likely that other related miR172 floral repressors are up-regulated as well.

Lack of flowering in UBI::Cg1 switchgrass has important implications, not only for biomass quality, but for prevention of transgene escape into native plant populations. A major impediment to using new transgenic crop plants is the need for containment of either transgenic seed or pollen. Spread of transgenes from pollen and seed dispersal has the potential to be a major ecological problem for growers using transgenic crops (38). The fact that Cg1 switchgrass does not flower presents an effective solution to this problem. Moreover, in grasses such as wheat, the flowering signal initiates reallocation of carbon resources from stem tissue to reproductive tissue, including seeds (39). By restricting flowering, this carbon stays in vegetative tissue, which should allow for increased carbohydrate levels as a basis for fermentation. Finally, in some annual plants flowering can act as a signal that promotes senescence and causes loss of vegetative carbon (40). Carbon loss from senescence is reduced in Cg1 transformants, and in fact, many transformants are effectively immortalized. The fact that Cg1 stems contain greater than twofold more starch supports the idea that flowering and starch degradation are interconnected. It is possible that starch destined for use during floral development is left unused in the Cg1 transformants, and thus accumulates in stems.

Cg1 switchgrass aerial stems store starch and initiate both roots and shoots, giving them both the appearance and function of a rhizome. It is possible that the lower juvenile nodes of all grasses have rhizome potential, and that overexpression of miR156 extends this potential to the upper regions of the plant. Although additional studies are needed to determine whether the presence of excess starch may make plants more susceptible to predation, we show that having extra starch may minimize the need for extensive pretreatment of the biomass. Starch is much easier to digest compared with cellulose and can simply be released through saccharification with amylase enzymes, which are significantly cheaper that cell wall degrading enzymes. Circumventing the pretreatment requirement also results in significant energy savings, because this process requires very high temperatures and the use of caustic chemicals. In addition, unlike other bioenergy crop plants such as sugarcane, dried starchy biomass can be stored long term and is easy to transport. Ultimately, this information can be readily transferable to other less genetically tractable species such as Miscanthus and sorghum, and may improve a variety of different plants for use as biofuel crops.

Materials and Methods

Vector Construction and Transformation.

The maize full-length Cg1 cDNA was cloned into the maize Ubiquitin cassette vector pUbi-BASK-Nos cassette, and then blunt-end ligated into the Agro binary vector pWBVec8. This binary vector was transformed into Alamo switchgrass (41) and into Brachypodium Bd21-3 (42). The same cDNA fragment was cloned into pENTR (Invitrogen), recombined into Agrobacterium binary pKGW, containing the 35S promoter NOS 3′ cassette, and then transformed into Arabidopsis Columbia plants by floral dipping.

Histology.

For plastic sections, plants were fixed overnight in FAA, dehydrated in an ethanol series, and embedded in JB-4 plastic per the manufacturer's instructions. Two-micrometer sections were made and stained for 30 s in TBO and then photographed using darkfield optics. For epidermal peels, hole punches of juvenile, adult, and Cg1-overexpressing leaves were made, fixed in 1% formaldehyde in PBS, washed several times with water, and then incubated with 0.1% Pectinolyase overnight (43). The next day, the epidermis was peeled off, dipped into TBO, washed, and photographed using brightfield optics.

Field Trials and Branch Counts.

Twenty independent UBI::Cg1-overexpressing switchgrass transformants and four wild-type plants were grown in 4 × 4 inch pots for 1–2 mo in the greenhouse, cut back, and then transplanted into the field in Berkeley, California in early June 2010. Total above-ground biomass from 17 of the surviving lines was harvested in late October 2010 and dried for 3 wk at 37 °C in a corn dryer before analysis. Tiller numbers were determined after harvest by counting stem stubs. To date, all Cg1 transformants have still not flowered either in the field or in the greenhouse, whereas target mimic negative control lines flowered after 6 mo.

To calculate significance, dry weight and primary branch number data were analyzed using a two-tailed, Student's t test with unequal variance. *P < 0.0001.

qPCR Analysis.

To quantify transcript levels, qPCR was done on a Bio-Rad CFX-96 real-time PCR machine. Five hundred nanograms of poly(A)+ purified RNA was used for each cDNA synthesis reaction. Approximately 5–10 ng of cDNA was included into each PCR with single color real-time detection using Sybr Green. All PCR reactions were done with three biological replicates of each sample and two technical replicates and normalized against the switchgrass actin gene as a reference using the delta Ct method. All primer sequences are available in SI Materials and Methods.

Analysis of Starch.

Freeze dried plant material from two biological replicates of each transformant class and two wild-type plants was ground for 1 min to a fine powder in a Kleco ball mill 8200 (Kleco). Alcohol insoluble residue was prepared by washing the samples with ethanol (70% vol/vol), chloroform/methanol (1:1 vol/vol), and acetone (once, thrice, and once, respectively). The samples were dried in a speed vac.

Approximately 100 mg of alcohol insoluble residue (AIR) was dispensed into 15 mL conical polypropylene tubes in duplicates. The samples were wetted with 200 μL ethanol (80% vol/vol). Immediately, 3 mL of thermostable α-amylase (100 U/mL in 100 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0) was added and the tubes incubated for 12 min at 100 °C in a Techne DB-3B heater with intermittent rigorous mixing after 4, 8, and 12 min. The samples were cooled on ice to room temperature and 100 μL of amyloglucosidase (3,300 U/mL) was added. After rigorous mixing, the samples were incubated for 30 min at 50 °C. The volume of the samples was adjusted to 10 mL with distilled water and the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 3,000 rpm. An aliquot of 1 mL of supernatant was transferred to a 2-mL screw-capped microcentrifuge tube and the glucose concentration was measured on the YSI 2700 Select Biochemistry Analyzer (YSI Life Sciences). Two technical replicates were performed for each sample.

Starch staining was done on razor blade hand sections of two biological replicates of field grown stems boiled in 95% ethanol, and then dipped in Lugol's potassium iodine solution, and then rinsed in water and mounted in glycerol.

Enzymatic Saccharification of Dilute Base Pretreated Biomass.

Field grown leaves were freeze dried and treated with dilute base, ground to a fine powder, and treated with Accellerase 1500 enzyme mix (Gencor). Each assay was done with ∼2 mg of material in 2-mL screw-cap tubes in 1 mL of 50 mM citrate buffer (pH. 4.5) including sodium azide to a final concentration of 0.01 mg/mL, at 50 °C under constant (mild) agitation for 20 h. A total of 2 μL of enzyme was used per sample. The Megazyme d-Glucose kit was used to measure the glucose content following the manufacturer's procedures on six technical replicates on single plants from each transformant class.

Dilute Acid Pretreatment.

Switchgrass samples from two biological replicates for each transformant class including two wild-type plants were presoaked in pressurized glass tubes at room temperature in 1.2% (wt/wt) sulfuric acid at 3% (wt/wt) total solid loading for at least 4 h. The glass tubes were then heated at 160 °C for 30 min. The acidic slurry was filtered through Whatman filter paper with a Buchner funnel. The recovered solids were washed with deionized water until the pH of the washed water reached 5.0.

Enzymatic Saccharification of Untreated and Dilute Acid Pretreated Biomass.

Batch enzymatic saccharification of pretreated and untreated biomass samples from two biological replicates of each class were carried out at 50 °C and 150 rpm in a reciprocating shaker. Two enzyme mixtures were used. One mixture was Accellerase 1500 (method I) and the other mixture contained Accellerase 1500 plus α-amylase and amyloglucosidase (method II). Each assay was done with ∼10 mg of material in 5 mL of 50 mM citrate buffer (pH. 4.5), including sodium azide, to a final concentration of 0.01 mg/mL, 10 μL of Accellerase 1500 plus 10 μL of Megazyme thermostable α-amylase, and 10 μL amyloglucosidase (only with method II) was added to each sample. Sampling was performed at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 24, 48, and 72 h. The Megazyme d-Glucose kit was used to measure the glucose content following the manufacturer's procedures. Two technical replicates were performed for each sample.

Additional methods and references can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Thant Niang for his help on the project, including the plastic sections and branch counts. Thanks go to David Hantz for greenhouse management and China Lunde for reviewing the manuscript and help with statistics. This work was supported by Department of Energy (DOE) Grant DE-A102-08ER15962 and Binational Agricultural Research and Development Grant IS-4249-09 (to S.H. and G.S.C.) and by DOE Grant DE-SC0004822 (to M.P. and S.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1113971108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Carroll A, Somerville C. Cellulosic biofuels. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:165–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence CJ, Walbot V. Translational genomics for bioenergy production from fuelstock grasses: Maize as the model species. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2091–2094. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poethig RS. Phase change and the regulation of shoot morphogenesis in plants. Science. 1990;250:923–930. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4983.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whaley WG, Leech JH. The developmental morphology of the mutant “Corn grass.”. Bull Torrey Bot Club. 1950;77:274–286. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poethig RS. Heterochronic mutations affecting shoot development in maize. Genetics. 1988;119:959–973. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.4.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abedon BG, Hatfield RD, Tracy WF. Cell wall composition in juvenile and adult leaves of maize (Zea mays L.) J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:3896–3900. doi: 10.1021/jf052872w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuck G, Cigan AM, Saeteurn K, Hake S. The heterochronic maize mutant Corngrass1 results from overexpression of a tandem microRNA. Nat Genet. 2007;39:544–549. doi: 10.1038/ng2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhoades MW, et al. Prediction of plant microRNA targets. Cell. 2002;110:513–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu G, Poethig RS. Temporal regulation of shoot development in Arabidopsis thaliana by miR156 and its target SPL3. Development. 2006;133:3539–3547. doi: 10.1242/dev.02521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwab R, et al. Specific effects of microRNAs on the plant transcriptome. Dev Cell. 2005;8:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie K, Wu C, Xiong L. Genomic organization, differential expression, and interaction of SQUAMOSA promoter-binding-like transcription factors and microRNA156 in rice. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:280–293. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.084475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xing S, Salinas M, Höhmann S, Berndtgen R, Huijser P. miR156-targeted and nontargeted SBP-box transcription factors act in concert to secure male fertility in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3935–3950. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.079343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommer F, et al. The CRR1 nutritional copper sensor in Chlamydomonas contains two distinct metal-responsive domains. Plant Cell. 2010;22:4098–4113. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.080069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang JW, Schwab R, Czech B, Mica E, Weigel D. Dual effects of miR156-targeted SPL genes and CYP78A5/KLUH on plastochron length and organ size in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1231–1243. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandikota M, et al. The miRNA156/157 recognition element in the 3′ UTR of the Arabidopsis SBP box gene SPL3 prevents early flowering by translational inhibition in seedlings. Plant J. 2007;49:683–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chuck G, Whipple C, Jackson D, Hake S. The maize SBP-box transcription factor encoded by tasselsheath4 regulates bract development and the establishment of meristem boundaries. Development. 2010;137:1243–1250. doi: 10.1242/dev.048348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu G, et al. The sequential action of miR156 and miR172 regulates developmental timing in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2009;138:750–759. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JW, Czech B, Weigel D. miR156-regulated SPL transcription factors define an endogenous flowering pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell. 2009;138:738–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi A, et al. The microRNA-regulated SBP-Box transcription factor SPL3 is a direct upstream activator of LEAFY, FRUITFULL, and APETALA1. Dev Cell. 2009;17:268–278. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yant L, et al. Orchestration of the floral transition and floral development in Arabidopsis by the bifunctional transcription factor APETALA2. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2156–2170. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathieu J, Yant LJ, Mürdter F, Küttner F, Schmid M. Repression of flowering by the miR172 target SMZ. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christensen AH, Sharrock RA, Quail PH. Maize polyubiquitin genes: Structure, thermal perturbation of expression and transcript splicing, and promoter activity following transfer to protoplasts by electroporation. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;18:675–689. doi: 10.1007/BF00020010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dudley M, Poethig RS. The heterochronic Teopod1 and Teopod2 mutations of maize are expressed non-cell-autonomously. Genetics. 1993;133:389–399. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fry SC, Mohler KE, Nesselrode BH, Franková L. Mixed-linkage beta-glucan : Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase, a novel wall-remodelling enzyme from Equisetum (horsetails) and charophytic algae. Plant J. 2008;55:240–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franco-Zorrilla JM, et al. Target mimicry provides a new mechanism for regulation of microRNA activity. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1033–1037. doi: 10.1038/ng2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein J, Saedler H, Huijser P. A new family of DNA binding proteins includes putative transcriptional regulators of the Antirrhinum majus floral meristem identity gene SQUAMOSA. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;250:7–16. doi: 10.1007/BF02191820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moose SP, Sisco PH. glossy15 controls the epidermal juvenile-to-adult phase transition in maize. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1343–1355. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.10.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukushima RS, Hatfield RD. Comparison of the acetyl bromide spectrophotometric method with other analytical lignin methods for determining lignin concentration in forage samples. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:3713–3720. doi: 10.1021/jf035497l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eimert K, Wang SM, Lue WI, Chen J. Monogenic recessive mutations causing both late floral initiation and excess starch accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1703–1712. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.10.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S, et al. Molecular evolution and selection of a gene encoding two tandem microRNAs in rice. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:4789–4793. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright L. Biomass energy data book. Department of Energy Information Bridge. 2007:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmer MR, Vogel KP, Mitchell RB, Perrin RK. Net energy of cellulosic ethanol from switchgrass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:464–469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704767105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper JP. The use of controlled life-cycles in the forage grasses and legumes. Herb Abstr. 1960;30:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Esbroeck GA, Hussey MA, Sanderson MA. Variation between Alamo and Cave-in-Rock switchgrass in response to photoperiodic extension. Crop Sci. 2003;43:639–643. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLaughlin SB, et al. High-value renewable energy from prairie grasses. Environ Sci Technol. 2002;36:2122–2129. doi: 10.1021/es010963d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Distelfeld A, Li C, Dubcovsky J. Regulation of flowering in temperate cereals. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kobayashi Y, Weigel D. Move on up, it's time for change—mobile signals controlling photoperiod-dependent flowering. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2371–2384. doi: 10.1101/gad.1589007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Felber F, Kozlowski G, Arrigo N, Guadagnuolo R. Genetic and ecological consequences of transgene flow to the wild flora. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2007;107:173–205. doi: 10.1007/10_2007_050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scofield GN, et al. Starch storage in the stems of wheat plants: Localization and temporal changes. Ann Bot (Lond) 2009;103:859–868. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcp010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sklensky DE, Davies PJ. Resource partitioning to male and female flowers of Spinacia oleracea L. in relation to whole-plant monocarpic senescence. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:4323–4336. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saathoff AJ, Sarath G, Chow EK, Dien BS, Tobias CM. Downregulation of cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase in switchgrass by RNA silencing results in enhanced glucose release after cellulase treatment. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vogel J, Hill T. High-efficiency Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Brachypodium distachyon inbred line Bd21-3. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:471–478. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0472-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallagher K, Smith LG. discordia mutations specifically misorient asymmetric cell divisions during development of the maize leaf epidermis. Development. 1999;126:4623–4633. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.