Abstract

Purpose

To assess clinical antimicrobial efficacy results obtained with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%, administered three times a day (TID) for 5 days, integrated across three clinical trials of bacterial conjunctivitis and to investigate any microbiological eradication failures.

Methods

Clinical microbiological eradication data from three randomized, double-masked, parallel group studies of patients with bacterial conjunctivitis (two vehicle controlled; one active controlled with moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution, 0.5%) were integrated. All bacterial samples isolated at baseline above the species-specific threshold value were subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Samples isolated at subsequent visits were subjected to susceptibility testing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) to investigate the cause of eradication failures and the potential for drug resistance development.

Results

Visit 2 (day 4 or 5) and visit 3 (day 8) overall microbiological eradication rates were 92.2% and 88.4% for besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension compared with 61.4% and 72.5% for vehicle and 91.6% and 85.7% for moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution. Visit 2 and visit 3 microbiological eradication rates for Gram-positive and Gram-negative isolates and for individual species were consistent with the overall eradication rates. The majority of observed eradication failures in any treatment group were due to the persistence of the pathogen isolated at baseline. Eradication failures in the besifloxacin treatment group were not associated with lower antimicrobial susceptibility at baseline. PFGE data showed that the majority of bacterial strains in eyes with eradication failures were identical to the strain isolated at baseline; these eradication failures were not associated with a lower antimicrobial susceptibility at the follow-up visit.

Conclusion

Treatment with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%, administered TID for 5 days resulted in microbiological eradication rates that were ≥ 90% across the three clinical studies for the common pathogens of bacterial conjunctivitis. The few eradication failures were not due to fluoroquinolone resistance at baseline and/or resistance development during treatment.

Keywords: besifloxcin, moxifloxacin, antimicrobial efficacy, bacterial conjunctivitis

Introduction

Bacterial conjunctivitis is a common eye infection characterized by marked hyperemia or redness of the eye, and mild-to-moderate purulent conjunctival discharge.1 Symptoms often include tearing, itching, and ocular irritation.1 The condition often presents suddenly in one eye and can readily spread to the other eye as a contagious disease.1,2 Although the disease is generally self-limited,3 treatment with a topical broad-spectrum ocular anti-infective shortens the duration of the disease, reduces contagious spread, and enhances the eradication of causative organisms.1–4 Treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis is mostly empiric and based upon the likely causative pathogens and local antibiotic resistance patterns.5 Therefore, the choice of therapy should ensure good activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms.

Besivance® (besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%; Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY) was approved in 2009 by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Besifloxacin is a novel 8-chlorofluoroquinolone with an N-1 cyclopropyl substituent. The amino azepinyl substituent at the C-7 position and the chlorine at the C-8 position give besifloxacin a unique structure and activity profile.6 In vitro studies show besifloxacin to be highly active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including multidrug-resistant strains,7 and to be rapidly bactericidal.8,9 The average maximum tear concentration (Cmax) of besifloxacin following instillation of a single drop of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%, in healthy volunteers is 610 ± 540 μg/g, while the total exposure (AUC0–24 [area under the curve from 0–24 hours]) is 1232 μg*h/g.10 The average maximum conjunctival tissue concentration is 2.3 ± 1.42 μg/g.11 The broad-spectrum antibacterial activity and pharmacokinetic properties of besifloxacin are consistent with observed effectiveness in bacterial conjunctivitis clinical trials.12–15

This paper reports on clinical microbial eradication rates obtained with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%, integrated across three multicenter, randomized, controlled, double-masked clinical trials.16–18 These clinical trials, two vehicle controlled and one active controlled, were conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%, compared with vehicle, or moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution, 0.5%, dosed topically three times daily (TID) for 5 days, in the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. The integrated analyses were undertaken to define how robust the microbiological eradication data observed with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension was across these three studies and to investigate the cause(s) of any eradication failures. The companion paper by Haas et al19 presents a detailed analysis of the distribution of baseline pathogens in these studies along with current antibacterial resistance profiles.

Methods

Studies

Microbiological data from three prospective, randomized, multicenter, double-masked clinical trials (two vehicle controlled and one active controlled; ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT00622908, NCT00347932, and NCT00348348) evaluating the clinical safety and efficacy of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%, in the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis were integrated. All trial protocols were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practices, the International Conference on Harmonization guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines. Individual study results, including clinical and safety findings, are reported elsewhere.16–18 The two vehicle-controlled studies16,17 were conducted at 35 and 58 sites, respectively, in the US, and enrolled 269 and 957 patients, respectively. The active-controlled study was conducted at 73 sites in the US plus 11 sites in Asia and enrolled 1167 patients.18

In all three studies, patients aged 1 year and older were eligible for participation if they had a clinical diagnosis of bacterial conjunctivitis as evidenced by grade 1 or greater purulent conjunctival discharge and bulbar conjunctival injection in at least one eye and had pinhole visual acuity of 20/200 or better in both eyes. Female patients of childbearing potential were required to use a reliable contraceptive method and have a negative pregnancy test prior to enrolment. Patients were excluded if they: had a known hypersensitivity to fluoroquinolones, besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, or any of the ingredients in the study medications; had used topical ophthalmic anti-inflammatory agents within 48 hours before or during the study or other topical ophthalmic solutions (including tear substitutes) within 2 hours before or during the study; had used antibacterial medications within 72 hours of study entry; or had suspected viral or allergic conjunctivitis, suspected iritis, a history of recurrent corneal erosion syndrome, or any active ulcerative keratitis.

Patients completed three study visits. At the first visit (day 1), patient’s eligibility was determined by: a clinical assessment of ocular signs and symptoms in both eyes; an eye examination that included pinhole visual acuity, biomicroscopy, and ophthalmoscopy; and culture of the infected eye(s). Cultures were taken from the cul-de-sac of the affected eye(s) prior to instillation of any medication, and samples were analyzed by a central laboratory for quantitative microbiology to enumerate and identify bacterial pathogens as well as to identify the presence of any co-infecting virus or yeast (details of the culturing methods are provided in the companion paper by Haas et al).19 The conjunctivitis was considered culture-confirmed if the bacterial colony count equaled or exceeded the threshold value for that species on the Cagle list as modified by Leibowitz.20,21 Patients were instructed to administer one drop of study medication TID at approximately 6-hour intervals for 5 days. Clinical assessments performed at visit 1 were repeated at visit 2 (day 4 [± 1]16 or day 5 [± 1]17,18 and visit 3 (day 8 or 9).16–18 The primary efficacy endpoints included clinical resolution of conjunctivitis, defined as the absence of both ocular discharge and bulbar conjunctival injection, and microbiological eradication of the baseline bacterial infection in culture-confirmed study eyes. Microbiological eradication was defined as the absence of all ocular bacterial species that were present at or above the Cagle threshold at baseline (visit 1).

In vitro susceptibilities to besifloxacin and comparator antibacterial agents were determined for all bacterial isolates at or above the Cagle threshold at baseline (visit 1) and any subsequent visit(s) (visit 2 and/or visit 3) regardless of treatment group. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by broth microdilution according to the procedure recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI),22,23 and resulting MIC values were interpreted according to the susceptibility criteria published by CLSI.24,25 Isolates from selected species were further characterized by their antimicrobial resistance phenotype as described in the companion paper by Haas et al.19

Integrated analyses

Because microbiological specimen collection was the same across the three studies, and laboratory analysis procedures were the same and also conducted at the same central laboratory across the three studies, microbiological results from all three studies were pooled for a comprehensive, integrated analysis. The proportions of individual species at or above threshold across the three studies were tabulated along with their in vitro susceptibilities and antimicrobial resistance phenotypes. Microbiological eradication rates for besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension and comparator treatments were integrated by combining individual study data listings for each treatment group at each follow-up visit. In all three studies, missing data and discontinued patients were imputed as microbiological eradication failures. While only one eye per patient (study eye) was considered for the primary efficacy endpoints in the original study analyses,16–18 both eyes could contribute samples to the integrated microbiological analysis if both eyes had signs and symptoms of bacterial conjunctivitis and the pathogenic organism in the nonstudy eye was different from the organism in the study eye. In addition, more than one species from each eye were included if each species met the Cagle criteria.20

Eradication failures

While clinical antimicrobial efficacy was initially characterized using a 4-point outcome scale in each study, where 0 = eradication, 1 = reduction, 2 = persistence, and 3 = proliferation (definitions provided in Table 1), microbiological eradication was evaluated on a binary scale (eradication/noneradication) for the primary efficacy endpoint reported in each study. Data listings for the noneradication categories (eg, reduction, persistence, proliferation) from each study were combined and used to characterize microbiological eradication failures in the integrated analysis. The initial characterization into noneradication categories was based on the assumption that when the infecting species was present at follow-up, it was the same strain as that present at baseline.

Table 1.

Microbiological eradication outcome scale

| Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| 0 = Eradication | Infecting species originally present at or above threshold on day 1 is absent in follow-up culture |

| 1 = Reduction | Infecting species originally present at or above threshold on day 1 is reduced to a count below threshold in follow-up culture |

| 2 = Persistence | Infecting species originally present at or above threshold on day 1 remains present at or above threshold in follow-up culture, but does not exceed the day 1 count |

| 3 = Proliferation | Infecting species originally present at or above threshold on day 1 is increased above day 1 count in follow-up culture |

To further investigate the potential cause(s) of observed microbiological eradication failures, several analyses were conducted. First, to determine if microbiological eradication failures were associated with antimicrobial susceptibility at baseline, the numbers of isolates eradicated/noneradicated at visit 2 and visit 3 with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension and moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution were plotted as a function of the besifloxacin or moxifloxacin MICs, respectively, for the pathogen at baseline. Secondly, to determine the contribution of new infections as opposed to persistence or proliferation of the strain present at baseline, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) testing was performed for all isolates that were recovered at or above threshold at both baseline and any follow-up visit.26,27 PFGE gel-banding patterns were captured by a digital imaging system, and isolate pairs were classified as concordant (closely related), discordant (different strain), and indeterminate or nontypeable by standardized criteria. Finally, to determine if microbiological failures were due to treatment-emergent resistance development, susceptibility results for any concordant isolate pairs was examined further using a ≥four-fold increase in MIC values for besifloxacin or moxifloxacin as indicative of antimicrobial resistance development during study treatment.

Results

Study populations

A total of 2393 patients were enrolled across the three studies, 2387 patients were randomized and treated, and of these 43.6% (1041/2387) were culture-confirmed. The integrated rate of culture-confirmed patients was consistent with that observed in the individual studies (43.9%,16 40.8%,17 and 45.9%18).

Pathogen distribution at baseline

In total, 1324 bacterial isolates were obtained at or above the Cagle threshold from the 1041 culture-confirmed patients across the three studies. Of these, 49.5% (656/1324), 22.5% (298/1324), and 27.9% (370/1324) were isolated from patients randomized to be treated with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, vehicle, or moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution, respectively. A total of 2.7% (28/1041) of the eyes yielding bacterial pathogens at or above threshold also tested positive for virus (adenovirus [n = 24] and herpes simplex virus [n = 4]).

Table 2 summarizes the baseline pathogens with an incidence ≥ 1% in any one of the treatment groups. The most frequently isolated species were Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus epidermidis and were similar across all treatment groups and all studies.16–18 Additional species isolated, along with an analysis of the differences between isolates from US and Asian sites as well as detailed results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing at baseline, are presented in the companion manuscript by Haas et al.19

Table 2.

Baseline pathogens with incidence ≥ 1% by treatment group and overall

| Organism | Treatment group, N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6% | Moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution, 0.5% | Vehicle | Overall | |

| All species | 656 (100.0) | 370 (100.0) | 298 (100.0) | 1324 (100.0) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 167 (25.5) | 90 (24.3) | 87 (29.2) | 344 (26.0) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 153 (23.3) | 66 (17.8) | 83 (27.9) | 302 (22.8) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 93 (14.2) | 56 (15.1) | 41 (13.8) | 190 (14.4) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 50 (7.6) | 41 (11.1) | 20 (6.7) | 111 (8.4) |

| Streptococcus mitis groupa | 19 (2.9) | 14 (3.8) | 12 (4.0) | 45 (3.4) |

| CDC coryneform group G | 16 (2.4) | 11 (3.0) | 2 (0.7) | 29 (2.2) |

| Streptococcus mitis | 10 (1.5) | 5 (1.4) | 5 (1.7) | 20 (1.5) |

| Streptococcus oralis | 11 (1.7) | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.0) | 18 (1.4) |

| Streptococcus spp.a | 8 (1.2) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.7) | 13 (1.0) |

Note: Isolates that were identified to the species level were listed separately.

Microbiological eradication rates

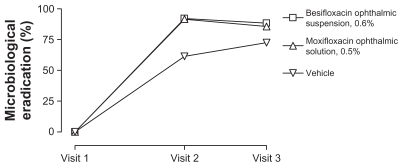

Overall microbiological eradication rates are presented in Figure 1. Visit 2 (day 4 or 5) microbiological eradication rates were 92.2%, 91.6%, and 61.4% in eyes treated with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution, and vehicle, respectively; while visit 3 (day 8) microbiological eradication rates were 88.4%, 85.7%, and 72.5%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Integrated microbiological eradication rates for isolates from eyes treated with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%, moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution, 0.5%, or vehicle. Visit 2 took place on day 4 (±1)16 or day 5 (±1)17,18 of study treatment; visit 3 took place on day 8 or 9.16–18

Visit 2 and visit 3 microbiological eradication rates for Gram-positive isolates, Gram-negative isolates, and for individual species are presented in Table 3. Consistent with overall eradication rates, treatment with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension resulted in microbiological eradication rates that were generally 90% or higher, and that were greater than those observed with vehicle treatment and similar to those observed with moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution. This pattern of microbiological eradication was observed for Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria and by individual species.

Table 3.

Microbiological eradication of Gram-positive isolates, Gram-negative isolates, and most prevalent species by treatment and visita

| Pathogen | Treatment, % (n/N) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6% | Moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution, 0.5% | Vehicle | ||||

| Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | |

| Gram positive | 92.2 (412/447) | 87.7 (392/447) | 89.8 (219/244) | 86.5 (211/244) | 58.5 (114/195) | 71.8 (140/195) |

| Gram negative | 92.3 (193/209) | 90.0 (188/209) | 95.2 (120/126) | 84.1 (106/126) | 67.0 (69/103) | 73.8 (76/103) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 91.0 (152/167) | 88.6 (148/167) | 94.4 (85/90) | 87.8 (79/90) | 64.4 (56/87) | 73.6 (64/87) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 87.1 (81/93) | 83.9 (78/93) | 85.7 (48/56) | 82.1 (46/56) | 39.0 (16/41) | 48.8 (20/41) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 94.0 (47/50) | 88.0 (44/50) | 87.8 (36/41) | 78.0 (32/41) | 55.0 (11/20) | 75.0 (15/20) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 92.8 (142/153) | 86.3 (132/153) | 90.9 (60/66) | 86.4 (57/66) | 56.6 (47/83) | 73.5 (61/83) |

Microbiological eradication failures

Table 4 presents microbiological outcomes based on the four-point outcome scale along with eradication failures imputed due to missing data by treatment and follow-up visit. For both active treatment groups, approximately half of the microbiological failures were due to persistence of the baseline pathogens at the follow-up visits (4.0% and 4.7% for besifloxacin, and 3.2% and 5.4% for moxifloxacin at visits 2 and 3, respectively), and half were due to imputed failures due to missing data (2.9% and 5.8% for besifloxacin, and 4.1% and 5.9% for moxifloxacin at visits 2 and 3, respectively). In contrast, the primary source of microbiological failure in the vehicle-treatment group was the observation of persistence/ proliferation of baseline pathogens at follow-up visits (19.8% and 13.4% for persistence, and 7.7% and 3.0% for proliferation at visits 2 and 3, respectively). The distribution of pathogens in the subset that were not eradicated did not differ from that in the subset of eradicated pathogens, regardless of treatment group (data not shown). In addition, there was no association between microbiological failures and co-infection with virus (data not shown).

Table 4.

Microbiological eradication outcomes by treatment and visitsa

| Treatment | n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success Eradicated | Observed failures | Imputed failures missing data | |||

| Reduction | Persistence | Proliferation | |||

| Besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension (N = 656) | |||||

| Visit 2 | 605 (92.2) | 3 (0.5) | 26 (4.0) | 3 (0.5) | 19 (2.9) |

| Visit 3 | 580 (88.4) | 1 (0.2) | 31 (4.7) | 6 (0.9) | 38 (5.8) |

| Moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution (N = 370) | |||||

| Visit 2 | 339 (91.6) | 3 (0.8) | 12 (3.2) | 1 (0.3) | 15 (4.1) |

| Visit 3 | 317 (85.7) | 5 (1.4) | 20 (5.4) | 6 (1.6) | 22 (5.9) |

| Vehicle (N = 298) | |||||

| Visit 2 | 183 (61.4) | 7 (2.3) | 59 (19.8) | 23 (7.7) | 26 (8.7) |

| Visit 3 | 216 (72.5) | 4 (1.3) | 40 (13.4) | 9 (3.0) | 29 (9.7) |

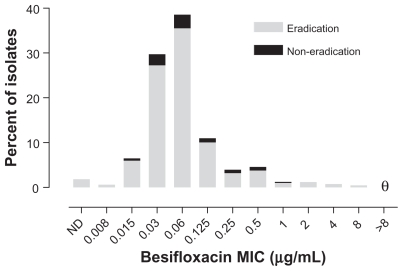

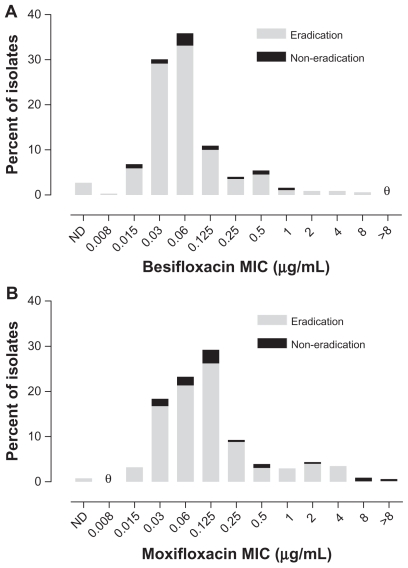

Figure 2 presents visit 2 microbiological eradication results for isolates from besifloxacin-treated eyes from all three studies relative to the besifloxacin MIC value for pathogens isolated at baseline. Figure 3 presents visit 2 microbiological eradication results for isolates from besifloxacin- and moxifloxacin-treated eyes in the active controlled study relative to the besifloxacin and moxifloxacin MIC values, respectively, for pathogens isolated at baseline in that study. The baseline MIC range for isolates from eyes treated with besifloxacin that were eradicated was 0.008–8 μg/mL. The MIC range for isolates from eyes treated with besifloxacin that resulted in eradication failures (all studies, n = 51; activecontrolled study, n = 22) was 0.015–1 μg/mL, indicating that the besifloxacin MIC at baseline was not the primary determinant of microbial eradication failures. Minimum inhibitory concentration values were higher overall in the moxifloxacin treatment group. The baseline MIC range for the moxifloxacin-treated isolates was 0.015 to >8 μg/ mL for the isolates that were eradicated (n = 339) and 0.03 to >8 μg/mL for the isolates that resulted in eradication failures (n = 31). However, of the latter, four isolates had moxifloxacin MIC values that were ≥2 μg/mL. Thus, 100% (16/16) of isolates from besifloxacin-treated eyes with besifloxacin MIC values of 2–8 μg/mL were successfully eradicated compared with 87.1% (27/31) of isolates from moxifloxacin-treated eyes with moxifloxacin MICs of 2 to >8 μg/mL. Analysis of visit 3 eradication rates for either besifloxacin- or moxifloxacin-treated isolates as a function of baseline MIC resulted in similar findings as those observed for visit 2 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Visit 2 microbiological eradication versus besifloxacin MIC distribution at baseline for isolates in the besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension treatment group across all three studies (N = 656). θ = nil.

Abbreviations: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; ND, MIC could not be determined.

Figure 3.

Visit 2 microbiological eradication versus MIC distribution at baseline in the active controlled study. (A) Eradication versus besifloxacin MIC distribution for isolates in the besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension treatment group (N = 329). (B) Eradication versus moxifloxacin MIC distribution for isolates in the moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution treatment group (N = 370). θ = nil.

Abbreviations: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; ND, MIC could not be determined.

PFGE results

Table 5 presents the distribution of bacterial isolate pairs with concordant and discordant PFGE results from eyes with microbiological eradication failures for both active and vehicle treatments. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis banding patterns showed that 86.4% (57/66) of isolate pairs from besifloxacin-treated eyes and 89.7% (35/39) of isolate pairs from moxifloxacin-treated eyes were concordant, indicating that the eradication failure was due to the presence of a strain that was genetically the same as the strain that was present at baseline. In contrast, 12.1% (8/66) and 10.3% (4/39) of isolate pairs from besifloxacin- and moxifloxacin-treated eyes, respectively, were discordant, indicating that these microbiological eradication failures were likely due to new infections with different strains of the same species rather than reinfection with or persistence of the baseline infecting strain. Among vehicle-treated eyes, the percentage of isolate pairs determined to be discordant was approximately half that observed for the active treatments.

Table 5.

Distribution of concordant and discordant isolate pairs from eyes with microbiological eradication failures

| Isolate pair | Treatment group, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6% (N = 66) | Moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution, 0.5% (N = 39) | Vehicle (N = 131) | Overall (N = 236) | |

| Concordant | 57 (86.4) | 35 (89.7) | 124 (94.7) | 216 (91.5) |

| Discordant | 8 (12.1) | 4 (10.3) | 6 (4.6) | 18 (7.6) |

| Indeterminanta | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) |

Note: Indeterminant pulsed-field gel electrophoresis results were obtained for a Streptococcus pneumoniae isolate pair obtained from the besifloxacin treatment group and a Streptococcus agalactiae isolate pair obtained from the vehicle treatment group.

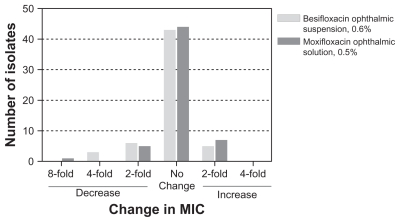

Figure 4 presents the change in MIC relative to baseline MIC within genetically concordant isolate pairs from eyes with microbiological eradication failures following active treatment. None of the concordant isolate pairs in the besifloxacin or moxifloxacin treatment groups showed an increase in MIC for besifloxacin or moxifloxacin that was greater than a single twofold dilution, indicating that none of the microbiological failures resulted from development of fluoroquinolone resistance during the treatment period.

Figure 4.

Fold-increase or decrease in MIC relative to baseline for concordant isolate pairs from eyes with microbiological eradication failures across the three studies.

Abbreviation: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

Discussion

Besifloxacin is a new fluoroquinolone, specif ically a chlorofluoroquinolone, for the topical treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Results from three randomized, double-masked, controlled studies demonstrated the safety and efficacy of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%, administered TID for 5 days in patients aged 1–98 years.16–18 The objectives of this report were to assess the consistency of the clinical antimicrobial efficacy of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%, integrated across these three clinical studies and to investigate the potential cause(s) for any microbiological eradication failures. The current analysis includes microbiological eradication data for 1324 bacterial pathogens across the three studies.

As expected, the most frequently isolated pathogens (H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and S. epidermidis) were consistent with those isolated in each of the pooled studies.16–18 Also, the relative frequencies of each of these pathogens were similar to those previously reported in patients with bacterial conjunctivitis.1,28 A detailed analysis of the causative organisms of bacterial conjunctivitis observed in the pooled studies along with their baseline antimicrobial susceptibility profiles is provided in the companion paper by Haas et al.19

Consistent with the individual study results,16–18 integrated microbiological eradication rates with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension were generally 90% or better at visit 2 (day 4 or 5), attesting to the reproducibility of the clinical microbiological eradication data for besifloxacin. Besifloxacin treatment resulted in microbiological eradication outcomes that were superior to those observed with vehicle treatment and similar to those observed with moxifloxacin treatment. This was the case for the overall eradication (ie, all isolates) for Gram-positive and Gram-negative isolates and individual species despite the presence of drug resistance phenotypes at baseline (see companion paper by Haas et al).19 In addition, 100% of the less frequently isolated pathogens from genera of ophthalmic interest (Moraxella spp. [n = 8], Neisseria spp. [n = 5], Pseudomonas aeruginosa [n = 4], and Serratia marcescens [n = 3]) treated with besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension were successfully eradicated (data not shown).

There were few microbiological eradication failures with either of the active treatments at either of the follow-up visits. There was no association between eradication failure and any particular bacterial species and/or the presence of viral co-infection. Of the failures, approximately half were imputed due to missing data, while the majority of the observed failures were due to persistence of the baseline pathogens at the follow-up visit. Few failures in the active-treatment groups were due to a reduction in bacterial count below the Cagle threshold without complete eradication. As expected, the proportion of microbial eradication failures in eyes treated with vehicle was higher, as was the percentage of eradication failures due to proliferation of the baseline pathogen. Visit 3 (days 8 or 9) microbiological eradication rates for both of the active treatments were slightly lower than those observed at visit 2. These results were consistent with the lack of antimicrobial treatment beyond day 5. As expected, microbial eradication failures decreased between visit 2 and visit 3 in vehicle-treated eyes, presumably due to individual host immune factors that characterize this self-limited disease.

Further investigation showed that microbiological eradication failures in the active treatment groups were not due to antimicrobial resistance at baseline or antimicrobial resistance development during study treatment. There was no apparent relationship between microbiological eradication failures and besifloxacin MIC values for the pathogen at baseline in besifloxacin-treated eyes, although the results were not as clear for isolates from moxifloxacin-treated eyes. In fact, all isolates with MICs ≥ 2 μg/mL from besifloxacin-treated eyes were successfully eradicated; whereas 11.8% of moxifloxacin-treated infections with MICs ≥ 2 μg/mL were not eradicated. The majority of isolate pairs from eyes with microbiological failures were determined to be concordant based on PFGE banding pattern, and susceptibility data for these isolate pairs did not reveal any ≥ four-fold increases in MIC, indicating that there was no development of fluoroquinolone resistance during the treatment period.

Most pathogens isolated from patients with bacterial conjunctivitis are components of the normal lid and nasopharyngeal flora.1,2,27–29 It follows that microbiological eradication failures observed in eyes treated with besifloxacin or moxifloxacin may not be actual eradication failures but rather the result of eradication and subsequent recolonization/reinfection of eyes with the same strains of bacteria present at baseline. It should be noted that the characterization of the majority of observed eradication failures being due to persistence of the baseline pathogen does not distinguish between true persistence and eradication followed by recolonization/reinfection. While recolonization/ reinfection with the baseline pathogen could explain the observed eradication failures, especially those additional failures observed after treatment termination in the active treatment groups, it should be noted that no anti-infective studied to date has yielded a 100% microbiological eradication rate. A recent systematic review of placebo-controlled bacterial conjunctivitis studies reported rates from 64.8% to 94.3% depending on the time of assessment.3 From the data presented here, it is clear that the relatively low rate (<10%) of microbiological eradication failures in besifloxacintreated eyes is not associated with decreased susceptibility of the causative bacteria at baseline and/or de novo development/ acquisition of drug resistance during treatment with this topical ophthalmic agent.

A limitation of each study included in this analysis is the absence of a nontreatment control. Both besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension and its vehicle contain benzalkonium chloride (BAK), a quaternary ammonium compound with bacteriostatic as well as bactericidal activity,30,31 as a preservative. BAK could in theory contribute to bacterial eradication rates in both the vehicle treatment group and besifloxacin treatment group. Without inclusion of a true nontreatment control, the full treatment effect of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension cannot be determined.

Conclusion

In summary, besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%, administered topically TID for 5 days demonstrated a consistently high rate of clinical microbiological eradication, generally 90% or better, for the causative agents of bacterial conjunctivitis across three independent, prospective, and double-masked bacterial conjunctivitis studies. Microbiological eradication failures were few and were not related to fluoroquinolone resistance at baseline and/or resistance development during treatment.

Acknowledgment

Species identification, antibacterial susceptibility testing, and PFGE analysis was performed by Covance Laboratory Services, Inc (Indianapolis, IN).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors were employess of Bausch & Lomb during the conduct of this analysis.

References

- 1.Høvding G. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(1):5–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamant JI, Hwang DG. Therapy for bacterial conjunctivitis. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1999;12(1):15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheikh A, Hurwitz B. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD001211. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001211.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller JB, McStay CM. Ocular infection and inflammation. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2008;26(1):57–72. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavuoto K, Zutshi D, Karp CL, Miller D, Feuer W. Update on bacterial conjunctivitis in South Florida. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward KW, Lepage J-F, Driot J-Y. Nonclinical pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and safety of BOL-303224-A, a novel fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agent for topical ophthalmic use. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23(3):243–256. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haas W, Pillar CM, Zurenko GE, Lee JC, Brunner LS, Morris TW. Besifloxacin, a novel fluoroquinolone, has broad-spectrum in vitro activity against aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(8):3552–3560. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00418-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas W, Pillar CM, Hesje CK, Sanfillippo CM, Morris TW. In vitro time-kill experiments with besifloxacin and gatifloxacin in the absence and presence of benzalkonium chloride. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(4):840–844. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Proksch JW, Granvil CP, Siou-Mermet R, Comstock TL, Paterno MR, Ward KW. Ocular pharmacokinetics of besifloxacin following topical administration to rabbits, monkeys, and humans. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2009;25(4):335–343. doi: 10.1089/jop.2008.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torkildsen G, Proksch JW, Shapiro A, Lynch SK, Comstock TL. Concentrations of besifloxacin, gatifloxacin, and moxifloxacin in human conjunctiva after topical ocular administration. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;(4):331–341. doi: 10.2147/opth.s9163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter NJ, Scott LJ. Besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6% Drugs. 2010;70(1):83–97. doi: 10.2165/11203820-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comstock TL, Karpecki PM, Morris TW, Zhang JZ. Besifloxacin: a novel anti-infective for the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;(4):215–225. doi: 10.2147/opth.s9604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang MH, Fung HB. Besifloxacin: a novel anti-infective for the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Clin Ther. 2010;32(3):454–471. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverstein BE, Allaire C, Bateman KM, Gearinger LS, Morris TW, Comstock TL. Efficacy and tolerability of besifloxacin 0.6% ophthalmic suspension administered twice daily for three days in the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis: a multicenter, double-masked, vehicle controlled, parallel-group study in adults and children. Clin Ther. 2011;33(1):13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karpecki P, Depaolis M, Hunter JA, et al. Besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6% in patients with bacterial conjunctivitis: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, 5-day efficacy and safety study. Clin Ther. 2009;31(3):514–526. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tepedino ME, Heller WH, Usner DW, et al. Phase III efficacy and safety study of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6% in the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(5):1159–1169. doi: 10.1185/03007990902837919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald MB, Protzko EE, Brunner LS, et al. Efficacy and safety of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6% compared with moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution, 0.5%, for treating bacterial conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(9):1615–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cagle G, Davis S, Rosenthal A, Smith J. Topical tobramycin and gentamicin sulfate in the treatment of ocular infections: multicenter study. Curr Eye Res. 1981;1(9):523–534. doi: 10.3109/02713688109069178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hass W, Gearinger LS, Usner DW, DeCory HH, Morris TW. Integrated analysis of three bacterial conjunctivitis trials of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6%: etiology of bacterial conjunctivitis and antibacterial susceptibility profile. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011 doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S23519. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leibowitz HM. Antibacterial effectiveness of ciprofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic solution in the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;(112 Suppl 4):29S–33S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. CLSI document M07-A6. sixth edition. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2003. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard. CLSI document M07-A7. seventh edition. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. CLSI document: M100-S14. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2004. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; fourteenth informational supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. CLSI document M100-S16. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2006. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; sixteenth informational supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ichiyama S, Ohta M, Shimokata K, Kato N, Takeuchi J. Genomic DNA fingerprinting by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as an epidemiological marker for study of nosocomial infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(12):2690–2695. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2690-2695.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(9):2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarabishy AB, Jeng BH. Bacterial conjunctivitis: a review for internists. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(7):507–512. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.7.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gigliotti F, Williams WT, Hayden FG, et al. Etiology of acute conjunctivitis in children. J Pediatr. 1981;98(4):531–536. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80754-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brook I, Pettit TH, Martin WJ, Finegold SM. Anaerobic and aerobic bacteriology of acute conjunctivitis. Ann Ophthalmol. 1979;11(3):389–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonnell G, Russell AD. Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action and resistance. Clin Microb Rev. 1999;12(1):147–179. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blondeau JM, Boros S, Hesje CK. Antimicrobial efficacy of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin with and without benzalkonium chloride compared with ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Chemother. 2007;19(2):146–151. doi: 10.1179/joc.2007.19.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]