Abstract

Objectives To determine the efficacy of intraoperative treatment with low dose tranexamic acid in reducing the rate of perioperative transfusions in patients undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy.

Design Double blind, parallel group, randomised, placebo controlled trial.

Setting One university hospital in Milan, Italy.

Participants 200 patients older than 18 years and undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy agreed to participate in the trial. Exclusion criteria were atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease treated with drug eluting stent, severe chronic renal failure, congenital or acquired thrombophilia, and known or suspected allergy to tranexamic acid.

Interventions Intravenous infusion of tranexamic acid or equivalent volume of placebo (saline) according to the following protocol: loading dose of 500 mg tranexamic acid 20 minutes before surgery followed by continuous infusion of tranexamic acid at 250 mg/h during surgery.

Main outcome measures Primary outcome: number of patients receiving blood transfusions perioperatively. Secondary outcome: intraoperative blood loss. Six month follow-up to assess long term safety in terms of mortality and thromboembolic events.

Results All patients completed treatment and none was lost to follow-up. Patients transfused were 34 (34%) in the tranexamic acid group and 55 (55%) in the control group (absolute reduction in transfusion rate 21% (95% CI 7% to 34%); relative risk of receiving transfusions for patients treated with tranexamic acid 0.62 (0.45 to 0.85); number needed to treat 5 (3 to 14); P=0.004). At follow-up, no patients died and the occurrence of thromboembolic events did not differ between the two groups.

Conclusions Intraoperative treatment with low dose tranexamic acid is safe and effective in reducing the rate of perioperative blood transfusions in patients undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00670345.

Introduction

In 2008, prostate cancer was the second most frequently diagnosed cancer in men worldwide, with an estimated 899 000 new cases (13% of all new cancer cases).1 In Europe the same year, prostate cancer was the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men, with an estimated 382 000 new cases (22%) and an estimated incidence of 93 per 100 000 men per year.2 Based on rates from 2005 to 2007, 16% of men born today will be diagnosed with prostate cancer during their lifetime.3 In the period from 1999 to 2006, 80% of individuals newly diagnosed with prostate cancer had localised disease.3 Active treatment is usually recommended for patients with localised prostate cancer and a good life expectancy. Radical prostatectomy is the only treatment for localised prostate cancer that has a cancer specific survival benefit when compared with watchful waiting in patients with low and intermediate risk localised prostate cancer and a life expectancy of more than 10 years.4Despite the introduction of laparoscopy (including robotic assisted approaches), open radical retropubic prostatectomy is still the standard surgical treatment for localised prostate cancer.5 One of the most important complications of this procedure is intraoperative and postoperative bleeding. Indeed, patients undergoing open radical prostatectomy often require blood transfusions.6 Red blood cell transfusion is fundamental to manage anaemia and is one of the few treatments that adequately restores tissue oxygenation when oxygen demand exceeds supply.7

Nonetheless, blood transfusions have rare but potentially serious adverse effects. Immune mediated effects include haemolytic reactions (acute and delayed), acute lung injury, and immunomodulation.8 Other effects include coagulopathic complications from massive transfusion, mistransfusion, and non-immune haemolysis.8 Transfusion associated infections are still a concern for allogeneic transfusions, especially because of the potential threat of emerging infectious disease agents.9 Blood transfusions are also associated with an increased mortality after major surgery.10 Additionally, blood is a scarce resource, and there are substantial economic costs associated with allogeneic transfusions.11

Disorders of haemostasis are often associated with prostate surgery, with the risk of bleeding being related to systemic and local activation of fibrinolysis.12 13 Tranexamic acid is a synthetic derivative of the amino acid lysine that exerts an antifibrinolytic action.14 A recent large randomised trial showed that tranexamic acid reduces mortality in patients with trauma and substantial haemorrhage.15 Tranexamic acid is the standard treatment used to reduce the rate of perioperative transfusion in cardiac surgery.16 Its efficacy has also been suggested in orthopaedic and liver surgery.17 18 The efficacy of tranexamic acid has not yet been shown in urological surgery. Treatment with tranexamic acid does not seem to adversely affect mortality and morbidity.19 Conversely, use of aprotinin is associated with an increased risk of death,20 and recombinant activated factor VII is associated with an increased risk of arterial thromboembolic events.21 Moreover, tranexamic acid is much cheaper than other haemostatic drugs.22

We conducted a randomised controlled trial to assess the efficacy of tranexamic acid in reducing the rate of blood transfusion in patients undergoing open radical prostatectomy and the long term safety of this treatment.

Methods

Trial design and participants

We undertook a single centre, double blind, parallel group, randomised, placebo controlled trial to determine the effect of intraoperative treatment with tranexamic acid on the number of patients receiving blood transfusions during the perioperative period (that is, during surgery and subsequent hospital care) in patients undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy. The study was conceived according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. After protocol approval by the hospital’s ethics committee, we conducted the study at San Raffaele Hospital, Milan, Italy, between April 2008 and May 2010, when we reached the planned number of patients enrolled.23 Our report accords with the CONSORT 2010 statement.24

Patients older than 18 years, undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy (associated with lymph node dissection when required for oncological radicality), and who provided written informed consent were eligible for the trial. Exclusion criteria were atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease treated with drug eluting stent, severe chronic renal failure (serum creatinine >180 µmol/L), congenital or acquired thrombophilia, and known or suspected allergy to tranexamic acid. Predonation of autologous blood was not an exclusion criterion.

Randomisation and masking

We created the randomisation sequence by permuted block randomisation with a block size of 20 and a 1:1 allocation generated by computer. The allocation sequence was prepared by an independent operator not otherwise involved in the trial and was concealed by opaque, sealed envelopes that were sequentially numbered. After the patients’ eligibility had been confirmed and the consent procedures completed, we randomly allocated patients to the intervention or placebo group by assigning them the sequentially numbered envelope with the lowest number. Trial participants, care providers, and data collectors were blinded to group assignment. A nurse, who was not involved in the study or in the care of the patients, opened the sealed envelope in a room away from the operating theatre and prepared the treatment. The bottle with the loading dose and the syringe for the continuous intravenous infusion were labelled only with the acronym of the trial name and the patient’s randomisation number. Bottles and syringe containing tranexamic acid were indistinguishable from those containing placebo (tranexamic acid is a colourless substance). After treatment preparation, the envelope was resealed.

Intervention

Patients randomly assigned to the intervention group received tranexamic acid (Ugurol, Rottapharm SpA, Milan, Italy; 0.5 g/5 mL vial) according to the following protocol: a loading dose of 500 mg of tranexamic acid diluted in 100 mL of saline was infused slowly intravenously 20 minutes before surgery, and a continuous intravenous infusion of tranexamic acid was given at a rate of 250 mg/h (2.5 mL/h, using undiluted tranexamic acid contained in the vials) from surgical incision until skin closure. Patients assigned to the control group received placebo (saline) with identical volumes and rates of infusion.

Patients were managed with general or spinal anaesthesia according to clinical needs and to the patient’s and surgeon’s preferences. No form of cell salvage was allowed during and after surgery.

To standardise treatment practice and the management of blood products, we used a mandatory transfusion protocol. If the haemoglobin concentration was lower than 80 g/L, or if it was lower than 100 g/L and associated with severe hypotension that did not respond to colloid infusion and inotropic drugs, one or more units of autologous whole blood or of allogeneic packed red blood cells were transfused to keep the concentration of haemoglobin above 80 g/L (or above 100 g/L in the case of severe hypotension).25 Each transfusion of a single unit of blood was followed by a haemoglobin test to assess the need for another transfusion. Preoperative autologous blood donations, if present, were transfused first. Transfusions were done during surgery, in the recovery room after surgery, or in the hospital ward on the basis of a blood test confirming that the patient met the criteria of the transfusion protocol. The decision to transfuse was made blind to patient group. One of the two doctors in charge of the trial (AC and AB) authorised transfusions, strictly following the above protocol.

Blood samples were collected before surgery, during surgery (just after prostate removal), and 4 hours and 24 hours after surgery. Topical haemostatic drugs used during surgery were: Floseal Hemostatic Matrix (Baxter International, Deerfield, IL, USA), Tabotamp (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA), and Lyostypt (B Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany).

Outcome measures

The main outcome measure was the number of patients receiving blood transfusions (either packed red blood cells or autologous whole blood) perioperatively (that is, from surgery until hospital discharge).

The secondary outcome was intraoperative blood loss—that is, the sum of blood volume aspired during surgery and blood volume absorbed in gauzes (calculated as the weight difference between gauzes before and after surgery).

We followed up patients by telephone one month and six months after randomisation to assess survival and occurrence of major cardiac, cerebrovascular, and thromboembolic events.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculations were based on a two sided α error of 0.05 and 80% power. Fifty per cent of patients undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy have been shown to receive blood transfusions in the perioperative period.26 With the use of tranexamic acid, we expected to see a reduction in the number of patients receiving blood transfusions of about 40%, as has been shown for other types of surgery.14 19 We calculated that we would need a sample size of 93 patients per group. Therefore, we planned to study 200 patients in total.

We undertook data analysis between November and December 2010. Data were stored electronically and analysed by use of IBM SPSS Statistics software version 19 and SAS software version 9, and are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or number (%) if not otherwise stated. Data analysis was by intention to treat, according to a pre-established analysis plan. We compared dichotomous data with the two tailed χ2 test, using Yates correction or Fisher exact test when appropriate. We compared continuous measures by analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Wilcoxon test. We reported results of blood product transfusions also as relative risks and numbers needed to treat (95% confidence intervals); we also calculated 95% confidence intervals for intraoperative blood loss. We used two sided significance tests throughout our data analysis. To exclude trends towards differences (P ≤0.2) or accidental differences (P<0.05) in demographic, medical, or surgical characteristics between the two groups from influencing our results, we did a supplemental analysis using a multivariate binary logistic model.

This study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier NCT00670345.

Results

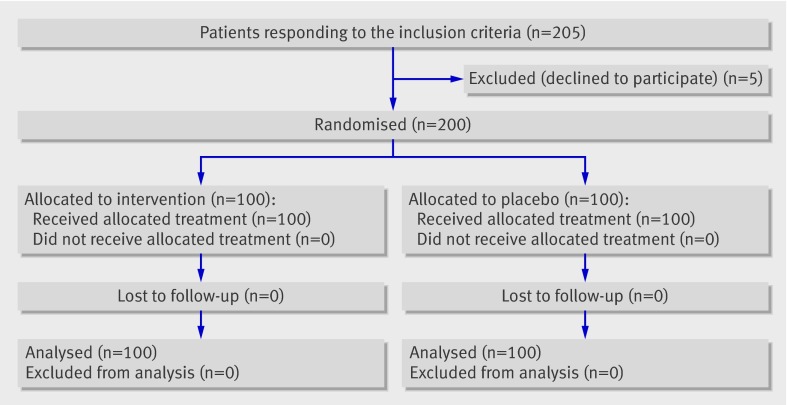

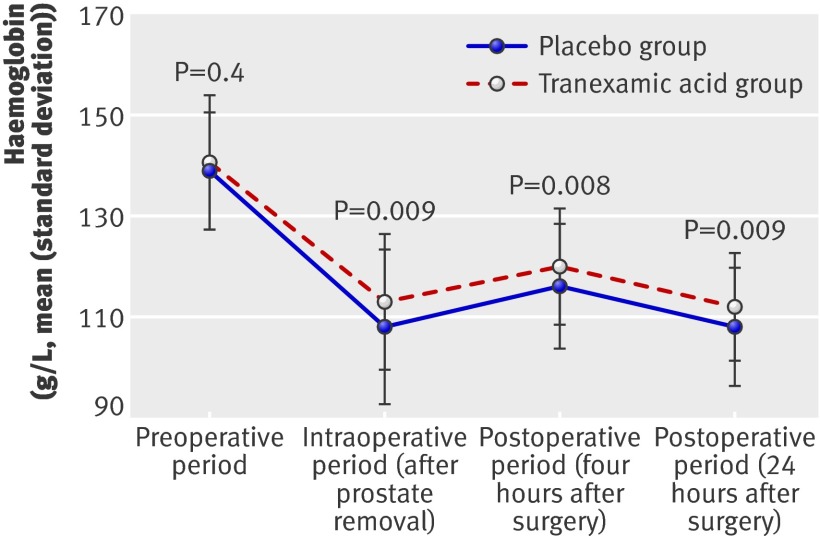

Of 205 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 200 gave written informed consent and underwent randomisation to receive tranexamic acid or placebo (fig 1). Treatment groups were balanced with respect to all baseline patient characteristics, with the exception of more patients in the tranexamic acid group receiving chronic drug treatment with calcium channel blockers (P=0.01) and a slightly lower mean platelet count in the patients of the tranexamic acid group (P=0.0502) (table 1). The mean concentration of preoperative haemoglobin was 139 g/L (standard deviation 1.15) in the control group and 141 g/L (1.29) in the treatment group (P=0.4) (fig 2). All patients received their intended treatment.

Fig 1 Trial profile

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of trial participants

| Placebo group (n=100) | Tranexamic acid group (n=100) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 64 (7.8) | 64 (7.4) | 0.8 |

| Weight (kg)* | 79 (11.9) | 80 (10.7) | 0.6 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)* | 26.5 (3.19) | 26.7 (3.23) | 0.6 |

| Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 | 15 (15) | 15 (15) | 0.9 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status score >2 | 5 (5) | 6 (6) | 0.9 |

| Lee’s revised cardiac risk index >1 | 5 (5) | 8 (8) | 0.5 |

| Hypertension | 37 (37) | 50 (50) | 0.087 |

| Coronary artery disease | 4 (4) | 5 (5) | 0.9 |

| Stroke | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0.9 |

| Preoperative systolic arterial pressure (mm Hg)* | 137 (17.4) | 138 (16.9) | 0.6 |

| Preoperative diastolic arterial pressure (mm Hg)* | 79 (9.6) | 80 (10.3) | 0.3 |

| Preoperative treatment | |||

| Antiplatelets | 7 (7) | 17 (17) | 0.0502 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 7 (7) | 20 (20) | 0.01 |

| Diuretics | 17 (17) | 16 (16) | 0.9 |

| β blockers | 9 (9) | 19 (19) | 0.06 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 31 (31) | 37 (37) | 0.4 |

| Hypolipidaemic drugs | 11 (11) | 13 (13) | 0.8 |

| Preoperative Gleason score† | 6 (6-7) | 6 (6-7) | 0.4 |

| Preoperative autologous blood donation | 41 (41) | 35 (35) | 0.5 |

| Nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy | 68 (68) | 72 (72) | 0.6 |

| General anaesthesia | 58 (58) | 52 (52) | 0.4 |

| Spinal anaesthesia | 42 (42) | 48 (48) | 0.4 |

| No of lymph node stations removed† | 4 (4-6) | 4 (4-6) | 0.9 |

Data are number (%) unless stated otherwise.

*Data are mean (standard deviation).

†Data are median (interquartile range).

Fig 2 Preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative concentrations of haemoglobin in intervention and control groups

The transfusion rate was significantly lower in the tranexamic acid group than in the placebo group (P=0.004) (table 2). The absolute reduction in the rate of blood transfusion was 21% (95% confidence intervals 7% to 34%), the relative reduction was 38% (14% to 55%), the relative risk of receiving blood transfusions for patients treated with tranexamic acid was 0.62 (0.45 to 0.85), and the number needed to treat was 5 (3 to 14). The rate of transfusion not only of packed red blood cells but also of autologous whole blood was significantly lower in patients receiving tranexamic acid than in those receiving placebo (table 2). Table 3 shows details of intraoperative and postoperative transfusions. No deviation from the transfusion protocol was reported.

Table 2.

Blood product transfusions during entire hospital stay

| Placebo group (n=100) | Tranexamic acid group (n=100) | P | Relative risk of event (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any blood product | 55 (55) | 34 (34) | 0.004 | 0.62 (0.45 to 0.85) |

| Packed red blood cells | 37 (37) | 22 (22) | 0.02 | 0.59 (0.38 to 0.93) |

| Autologous whole blood | 25 (25) | 13 (13) | 0.04 | 0.52 (0.28 to 0.96) |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 0.9 | 0.66 (0.11 to 3.9) |

Data are number (%) unless stated otherwise.

Table 3.

Blood product transfusion during different phases of hospital stay

| During surgery | In recovery room | After discharge from recovery room | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) of patients transfused | No (%) of patients transfused | No (%) of patients transfused | P, relative risk of event (95% CI) | No (%) of patients transfused | P, relative risk of event (95% CI) | |||

| Packed red blood cells | ||||||||

| Placebo group | 28 (28) | P=0.008, 0.43 (0.23 to 0.79) | 3 (3) | P=0.6, 0.33 (0.04 to 3.15) | 14 (14) | P=0.8, 0.86 (0.42 to 1.76) | ||

| Tranexamic acid group | 12 (12) | 1 (1) | 12 (12) | |||||

| Autologous whole blood | ||||||||

| Placebo group | 23 (23) | P=0.02, 0.43 (0.22 to 0.86) | 2 (2) | P=0.9, 1.5 (0.26 to 8.79) | 1 (1) | P=0.9, 1 (0.06 to 15.77) | ||

| Tranexamic acid group | 10 (10) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | |||||

| Packed red blood cells or autologous whole blood (or both) | ||||||||

| Placebo group | 47 (47) | P≥0.001, 0.47 (0.30 to 0.71) | 5 (5) | P=0.9, 0.8 (0.22 to 2.89) | 15 (15) | P=0.8, 0.86 (0.43 to 1.73) | ||

| Tranexamic acid group | 22 (22) | 4 (4) | 13 (13) | |||||

| Any blood product | ||||||||

| Placebo group | 47 (47) | P≥0.001, 0.47 (0.30 to 0.71) | 5 (5) | P=0.9, 0.8 (0.22 to 2.89) | 15 (15) | P=0.8, 0.86 (0.43 to 1.73) | ||

| Tranexamic acid group | 22 (22) | 4 (4) | 13 (13) | |||||

The mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower in the tranexamic acid group than in the placebo group (1103 mL (standard deviation 500.8) v 1335 mL (686.5), difference 232 mL (95% confidence intervals 29.7 to 370.7); P=0.02) (table 4). Furthermore, haemoglobin concentrations during surgery and the first day after surgery were higher in the intervention group than in the placebo group (fig 2, table 5). Results from all other blood tests after randomisation were similar in the two groups (table 5). Volume of intravenous fluids, use of topical haemostatic drug, length of surgery, postoperative fluid drain losses, and length of hospital stay were similar in the two groups (table 6).

Table 4.

Intraoperative blood loss

| Volume (mL) | Placebo group (n=100) | Tranexamic acid group (n=100) | P | Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suctioned blood | 1012 (608.1) | 810 (390.2) | 0.009 | 202 (59 to 345) |

| Blood absorbed in gauzes | 322 (151.8) | 293 (188.6) | 0.053 | 29 (−19 to 78) |

| Total intraoperative blood loss | 1335 (686.5) | 1103 (500.8) | 0.01 | 232 (30 to 371) |

Data are mean values (standard deviation) unless stated otherwise.

Table 5.

Preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative blood tests of study patients

| Blood test/study group | Preoperative | Intraoperative period (after prostate removal) | Postoperative period | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 hours after surgery | 24 hours after surgery | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P | Mean (SD) | P | Mean (SD) | P | ||||

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | ||||||||||

| Placebo | 139 (11.5) | 108 (15.4) | P=0.009 | 116 (12.5) | P=0.008 | 108 (11.6) | P=0.009 | |||

| Tranexamic acid | 141 (12.9) | 113 (13.4) | 120 (11.6) | 112 (10.7) | ||||||

| Platelet count (109/L) | ||||||||||

| Placebo | 214 (56.9) | 179 (49.3) | P=0.064 | 175 (48.8) | P=0.2 | 175 (45.5) | P=0.4 | |||

| Tranexamic acid | 200 (44.2) | 167 (41.7) | 167 (40.2) | 169 (36.8) | ||||||

| International normalised ratio | ||||||||||

| Placebo | 1.04 (0.06) | 1.22 (0.15) | P=0.3 | 1.19 (0.09) | P=0.8 | 1.21 (0.10) | P=0.4 | |||

| Tranexamic acid | 1.04 (0.06) | 1.25 (0.24) | 1.19 (0.1) | 1.23 (0.09) | ||||||

| Prothrombin time ratio | ||||||||||

| Placebo | 1.01 (0.07) | 1.03 (0.15) | P=0.9 | 0.98 (0.09) | P=0.7 | 1.05 (0.07) | P=0.7 | |||

| Tranexamic acid | 1.00 (0.07) | 1.04 (0.18) | 0.99 (0.10) | 1.05 (0.08) | ||||||

| D-dimers (µg/L) | ||||||||||

| Placebo | 450 (510) | 1000 (2780) | P=0.5 | 370 (130) | P=0.5 | 1430 (3340) | P=0.4 | |||

| Tranexamic acid | 380 (230) | 720 (2480) | 340 (70) | 1000 (2570) | ||||||

| Antithrombin (%) | ||||||||||

| Placebo | 88 (11.8) | 67 (12.3) | P=0.9 | 83 (10.6) | P=0.9 | 75 (11.1) | P=0.9 | |||

| Tranexamic acid | 85 (15.1) | 67 (12.1) | 84 (6.9) | 75 (11.2) | ||||||

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | ||||||||||

| Placebo | 82 (14.1) | – | – | 81 (15.0) | P=0.3 | 84 (20.3) | P=0.3 | |||

| Tranexamic acid | 84(19.5) | – | 85 (18.6) | 88 (21.2) | ||||||

SD=standard deviation.

Table 6 .

Other intraoperative and postoperative variables monitored

| Placebo group (n=100) | Tranexamic acid group (n=100) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume of crystalloids infused intraoperatively (mL) | 3660 (1140) | 3658 (1180) | 0.9 |

| Volume of colloids infused intraoperatively (mL) | 350 (366.6) | 286 (340.2) | 0.2 |

| Topical haemostatic drug use during surgery* | 44 (44) | 37 (37) | 0.3 |

| Surgery length (min) | 166 (44) | 159 (40) | 0.3 |

| Time spent in recovery room (min) | 58 (34) | 50 (25) | 0.074 |

| Volume of crystalloids infused during postoperative stay in hospital (mL) | 4773 (2282) | 4640 (2461) | 0.7 |

| Length of postoperative hospitalisation (days) | 9 (4.3) | 9 (4.3) | 0.9 |

| Fluid drain loss, 0-48 h postoperatively (mL) | 412 (244.3) | 361 (366.0) | 0.2 |

All data are mean (standard deviation) unless stated otherwise.

*Data are number of patients (%).

The median number of units of blood transfused to each patient was significantly reduced in the tranexamic acid group (0 (interquartile range 0-1)) compared with the placebo group (1 (0-1.5)) (P=0.004).

The web table provides details about autologous blood predonation and reinfusion. Preoperative haemoglobin concentration was 137 g/L (standard deviation 13.7) for patients who made autologous blood donations and 138 g/L (11.3) for patients who did not make donations (P=0.7).

A multivariate analysis showed that tranexamic acid was the only independent predictor of reduced risk of blood transfusion (relative risk 0.64, 95% confidence intervals 0.45 to 0.9) when we adjusted for all the prerandomisation variables with a non-significant trend (P<0.2) towards a difference between the groups. No adverse reaction related to blood transfusions was reported. No patient received aprotinin or recombinant activated factor VII as concomitant or rescue intervention.

We completed the one month and six month follow-up for all 200 patients; we did not record any death. At one month follow-up, we recorded two thromboembolic events in two patients in the control group (both deep vein thrombosis in the lower limb) and none in the tranexamic acid group. At six month follow-up, we recorded three more thromboembolic events in three patients in the control group (one myocardial infarction, one pulmonary thromboembolism, and one deep vein thrombosis in the lower limb) and two events in two patients in the tranexamic acid group (one myocardial infarction, and one deep vein thrombosis in a lower limb). In total, we recorded five thromboembolic events in the control group and two in the intervention group (relative risk in intervention group 0.4 (95% confidence intervals 0.09 to 1.74); P=0.4).

Discussion

Principal findings

Our study shows that intraoperative treatment with low dose tranexamic acid significantly reduces the rate of blood transfusions in urological surgery. Furthermore, we recorded no increase in thromboembolic events at six months’ follow-up. The 232 mL mean reduction of intraoperative blood loss in the tranexamic acid group was not only statistically significant but also of clinical relevance, because 38% fewer patients needed transfusion and perioperative anaemia was less severe than in the placebo group.

Intraoperative treatment with tranexamic acid reduced not only exposure to allogeneic blood, but also the need for autologous transfusions. This finding could contribute to recent doubts about the usefulness and cost effectiveness of preoperative autologous donation in this type of oncological surgery.27 28 Tranexamic acid inhibited fibrinolysis while having no apparent effect on laboratory blood clotting parameters. A suggested explanation for this finding is that tranexamic acid accumulates in the extracellular space of tissues where it inhibits tissue fibrinolysis29; this could explain why stabilisation of the blood clots by this drug is associated with no apparent effect on laboratory blood clotting parameter.

Comparison with other studies

We are unaware of any previously published randomised study investigating the use of tranexamic acid in open radical prostatectomy. In a randomised study on patients undergoing endoscopic prostate surgery for benign disease, treatment with tranexamic acid significantly reduced intraoperative bleeding but did not reduce postoperative rates of blood transfusion.29 The researchers used an entirely different treatment schedule in this study (2 g tranexamic acid by mouth thrice daily on the operative and first postoperative day, with no intravenous infusion of tranexamic acid during surgery), and did not have a long term follow-up or a clear power calculation.

Although radical prostatectomy is a very common surgical intervention, only two randomised controlled trials have shown a non-surgical strategy that is effective at reducing the transfusion rate in this setting.

In 2003, Friederich and colleagues suggested that an intraoperative infusion of recombinant activated factor VII significantly reduced perioperative blood loss and the rate of transfusion.30 This study had some limitations: it included far fewer patients than our study (n=36), had an unclear power calculation (based on the expected reduction in blood loss rather than the expected reduction in transfusion rate), and did not have a long term follow-up. The absence of a long term follow-up is particularly important because of a potential link between increased risk of mortality and thrombotic events and haemostatic drug use. In particular, aprotinin was recently withdrawn from the market after being associated with an increased risk of death.20 The use of off label recombinant activated factor VII to control perioperative haemorrhage in patients with no known congenital haemostasis and coagulation defects has recently been questioned by meta-analyses reporting a significantly increased risk of perioperative stroke in cardiac surgery31 and of arterial thromboembolic events when using high doses in the overall population, especially among the elderly.21 Tranexamic acid is now the only drug that has been shown to improve haemostatic function without being associated with an increased risk of thrombotic adverse events, also at long term follow-up.14 15 19 20

Induced hypotension by neuraxial anaesthesia is the only non-pharmacological and non-surgical strategy that reduces the rate of transfusions in prostatectomy. In 2006, O’Connor and colleagues showed that controlled hypotension using a combined technique (epidural and general anaesthesia) during surgery significantly reduced the rate of transfusions and perioperative blood loss compared with general anaesthesia alone.32 However, this intervention has not been widely accepted or incorporated into surgical routine.

Our randomised trial answers to the claim of a recent Cochrane review that large randomised controlled trials are needed to assess the efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in surgical procedures different from cardiac surgery.19

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Intraoperative treatment with low dose tranexamic acid is attractive because it is a very simple intervention and because tranexamic acid is a relatively inexpensive drug (compared with aprotinin and recombinant activated factor VII) that is not covered by patent. Moreover, our trial inclusion criteria were very broad and consequently almost all patients undergoing radical prostatectomy could be treated with tranexamic acid. Our study has a six month follow-up that assessed not only mortality, but also the occurrence of thromboembolic events in trial participants.

Conversely, data from our long term follow-up do not have sufficient power to make a definitive conclusion about safety: we recorded very few adverse events, and we recorded these events only if there was clinical evidence, therefore, we could have under-reported the frequency of these events. However, the number of thromboembolic events was lower in the tranexamic acid group than in the control group, and our data accord with those from other studies and reviews that have not recorded an increased risk of non-fatal thromboembolic complications associated with tranexamic acid use.14 15 19 20 33 Another possible limitation is that the method of concealment of the allocation sequence by opaque, sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes might be considered suboptimal compared with other expensive and remote methods of randomisation.

Intraoperative treatment with low dose tranexamic acid could also be considered in other settings of urological surgery where major perioperative bleeding could happen, such as cystectomy, nephrectomy, and renal cancer tumorectomy.

What is already known on this topic

No randomised controlled trial has yet investigated whether the use of tranexamic acid during open radical prostatectomy reduces the rate of perioperative transfusions

What this study adds

Intraoperative treatment with tranexamic acid is effective in reducing the rate of perioperative blood transfusions in patients undergoing urological surgery

Contributors: All authors took part in all stages of the study, from design to writing and editing the manuscript. AC, AB, and EB participated in patient recruitment and undertaking of the study. GMC undertook perioperative management during the study and monitored patients. AZ, PR, and FM participated in the design of the study. GB did the data analysis and interpretation, and GL and GB wrote the manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study (including statistical reports and tables) and are responsible for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. GL is the guarantor of the study.

Funding: Provided by the Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care of San Raffaele Hospital.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the unified competing interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: the study was funded by the Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care of San Raffaele Hospital; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the ethics committee at the San Raffaele Hospital.

Patient consent: We received written informed consent for trial inclusion. Although we did not obtain informed consent for data sharing, the presented data were anonymised with a low risk of identification.

Data sharing: Dataset available from GL.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d5701

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Web table: Details of autologous blood predonations and reinfusions

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008, Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No10. 2010. http://globocan.iarc.fr.

- 2.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:765-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2007. 2010. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007/.

- 4.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Filén F, Ruutu M, Garmo H, Busch C, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in localized prostate cancer: the Scandinavian prostate cancer group-4 randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1144-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finkelstein J, Eckersberger E, Sadri H, Taneja SS, Lepor H, Djavan B. Open versus laparoscopic versus robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: the European and US experience. Rev Urol 2010;12:35-43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ficarra V, Novara G, Artibani W, Cesatri A, Galfano A, Graefen M, et al. Retropubic, laparoscopic, and robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: a systematic review and cumulative analysis of comparative studies. Eur Urol 2009;55:1037-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang JK, Klein HG. Red blood cell transfusion in the treatment and management of anaemia: the search for the elusive transfusion trigger. Vox Sang 2010;98:2-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hendrickson JE, Hillyer CD. Noninfectious serious hazards of transfusion. Anesth Analg 2009;108:759-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perkins HA, Busch MP. Transfusion-associated infections: 50 years of relentless challenges and remarkable progress. Transfusion 2010;50:2080-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karkouti K, Wijeysundera DN, Yau TM, Beattie WS, Abdelnaem E, McCluskey SA, et al. The independent association of massive blood loss with mortality in cardiac surgery. Transfusion 2004;44:1453-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitaker BI, Green J, King MR, Leibeg LL, Mathew SM, Schlumpf KS, et al. The 2007 national blood collection and utilization survey report. 2010. www.hhs.gov/ash/bloodsafety/2007nbcus_survey.pdf.

- 12.Ziegler S, Ortu A, Reale C, Proietti R, Mondello E, Tufano R, et al. Fibrinolysis or hypercoagulation during radical prostatectomy? An evaluation of thrombelastographic parameters and standard laboratory tests. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2008;25:538-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen JD, Gram J, Holm-Nielsen A, Fabrin K, Jespersen J. Post-operative blood loss after transurethral prostatectomy is dependent on in situ fibrinolysis. Br J Urol 1997;80:889-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn CJ, Goa KL. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in surgery and other indications. Drugs 1999;57:1005-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CRASH-2 trial collaborators, Shakur H, Roberts I, Bautista R, Caballero J, Coats T, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Society of Thoracic Surgeons Blood Conservation Guideline Task Force, Ferraris VA, Brown JR, Despotis GJ, Hammon JW, Reece TB. 2011 update to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists blood conservation clinical practice guidelines. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:944-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kagoma YK, Crowther MA, Douketis J, Bhandari M, Eikelboom J, Lim W. Use of antifibrinolytic therapy to reduce transfusion in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery: a systematic review of randomized trials. Thromb Res 2009;123:687-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molenaar IQ, Warnaar N, Groen H, Tenvergert EM, Slooff MJ, Porte RJ. Efficacy and safety of antifibrinolytic drugs in liver transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Transplant 2007;7:185-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry DA, Carless PA, Moxey AJ, O′Connell D, Stokes BJ, Fergusson DA, et al. Anti-fibrinolytic use for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;3:CD001886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fergusson DA, Hébert PC, Mazer CD, Fremes S, MacAdams C, Murkin JM, et al. A comparison of aprotinin and lysine analogues in high-risk cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2319-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levi M, Levy JH, Andersen HF, Truloff D. Safety of recombinant activated factor VII in randomized clinical trials. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1791-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardone D, Klein AA. Perioperative blood conservation. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2009;26:722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principle for medical research involving human subjects. 2011. www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html.

- 24.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:834-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein HG, Spahn DR, Carson JL. Red blood cell transfusion in clinical practice. Lancet 2007;370:415-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Touijer K, Eastham JA, Secin FP, Romero Otero J, Serio A, Stasi J, et al. Comprehensive prospective comparative analysis of outcomes between open and laparoscopic radical prostatectomy conducted in 2003 to 2005. J Urol 2008;179:1811-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacIvor D, Nelson J, Triulzi D. Impact of intraoperative red blood cell salvage on transfusion requirements and outcomes in radical prostatectomy. Transfusion 2009;49:1431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O′Hara JF Jr, Sprung J, Klein EA, Dilger JA, Domen RE, Piedmonte MR. Use of preoperative autologous blood donation in patients undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urology 1999;54:130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rannikko A, Pétas A, Taari K. Tranexamic acid in control of primary hemorrhage during transurethral prostatectomy. Urology 2004;64:955-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friederich PW, Henny CP, Messelink EJ, Geerdink MG, Keller T, Kurth KH, et al. Effect of recombinant activated factor VII on perioperative blood loss in patients undergoing retropubic prostatectomy: a double-blind placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet 2003;361:201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ponschab M, Landoni G, Biondi-Zoccai G, Bignami E, Frati E, Nicolotti D, et al. Recombinant activated factor VII increases stroke in cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2011. [published online 17 May]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.O’Connor PJ, Hanson J, Finucane BT. Induced hypotension with epidural/general anesthesia reduces transfusion in radical prostate surgery. Can J Anaesth 2006;53:873-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CRASH-2 Collaborators (Intracranial Bleeding Study). Effect of tranexamic acid in traumatic brain injury: a nested randomised, placebo controlled trial (CRASH-2 Intracranial Bleeding Study). BMJ 2011;343:d3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web table: Details of autologous blood predonations and reinfusions