Abstract

Aim:

To compare the cleaning efficiency of manual and rotary instrumentation in the apical third of the root canal system.

Materials and Methods:

In group 1 (n=10), instrumentation was performed with stainless steel K-file; in group 2 (n=10), it was done with hand ProTaper files; and in group 3 (n=10), instrumentation was done with ProTaper rotary. Distilled water was used for irrigation. The apical third was sectioned transversally and histologically processed. The cross sections were examined under optic microscope and debris was measured using Motic software.

Results:

Instrumentation with stainless steel K-files showed minimum amount of debris, followed by ProTaper hand files, and rotary ProTaper files were least effective with maximum amount of debris; however, there were no significant differences between the three experimental groups.

Conclusions:

Both the manual and rotary instrumentation are relatively efficient in cleaning the apical third of the root canal system and the choice between manual and rotary instrumentation should depend on case to case basis.

Keywords: Apical third, cleaning efficiency, debris, ProTaper

INTRODUCTION

One of the most important objectives during root canal instrumentation is the removal of vital and / or necrotic pulp tissue, infected dentine and dentine debris in order to eliminate most of the microorganisms from the root canal system (European Society of Endodontology 1994, American Association of Endodontists 1998).

Debris is defined as dentine chips and residual vital or necrotic pulp tissue attached to the root canal wall, which in most cases is infected.[1] The apical third of the root canal is the most difficult area to clean due to complex anatomy of this region like deltas, lateral canals, isthmuses and ramifications.[2]

Despite the advances made in instruments and instrumentation techniques, the design and the physical limitations of the endodontic instruments can lead to inadequate cleaning of the root canal system. Shaping procedures can be completed more easily, quickly and predictably using NiTi rotary instruments, but effective cleansing of the root canal system, especially in the apical one third, has not yet been demonstrated.[2–4] Both manual and mechanical instrumentation leave debris in the root canal space.[5,6]

The introduction of hand ProTaper instruments and the paucity of studies comparing hand and rotary ProTaper instruments prompted us to carry out this study. The aim of the study was to compare the cleaning efficacy of manual and rotary instruments in the apical third of the root canal system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thirty-three extracted, single-rooted human mandibular first premolars with single canal and completely formed roots were selected and placed in 3% sodium hypochlorite for 30 minutes and then stored in normal saline.

The teeth were randomly divided into three groups of 10 teeth each.

Three teeth were used as negative controls in which no procedure was carried out.

Conventional access was made and working length was determined 0.5 mm short of the apical foramen using #10 K-file. To standardize the patency of the apical foramen, teeth with apical diameter larger than size 15 K-file were excluded from the study. Apical foramen was sealed using modeling wax.

Group 1

Teeth were prepared with stainless steel K-file (Mani INC, Tochigi, Japan). Coronal flaring was performed with Gates Glidden burs #2 and #3.

Instrumentation was done with double flare technique, using balanced force motion, till apical size 30.

Group 2

Teeth were prepared with ProTaper Universal hand files (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) in sequential order till F3 at the working length according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Group 3

Teeth were prepared with ProTaper Universal rotary files (Dentsply Maillefer) with gentle in-and-out motion till F3 at the working length according to the manufacturer's instructions using an endodontic engine (X-Smart; Dentsply Maillefer) at 250 rpm.

Teeth were irrigated 1 mm short of the working length with 2 ml of distilled water after the use of each instrument , and 10 ml of distilled water was used as final flush. Irrigation was performed using 30-G Max-i-probe needle (Dentsply, Rinn, Elgin, IL, USA).

The apical third of each root was sectioned transversally and stored in 10% formalin for 12 hours till histological processing. The samples were then washed, decalcified with 10% nitric acid and embedded in paraffin. Three cross sections (5 μm) were randomly obtained from each tooth. A total of 99 sections were obtained and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The cross sections were examined with an optic microscope (×40) coupled to a computer. The images were recorded and the percentage of debris was calculated using Motic software in square micrometers. The data were statistically analyzed using nonparametric analysis of variance (ANOVA) Kruskal–Wallis test and the level of significance was set at P < 0.05. SPSS version 12 software was used for statistical analysis.

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS

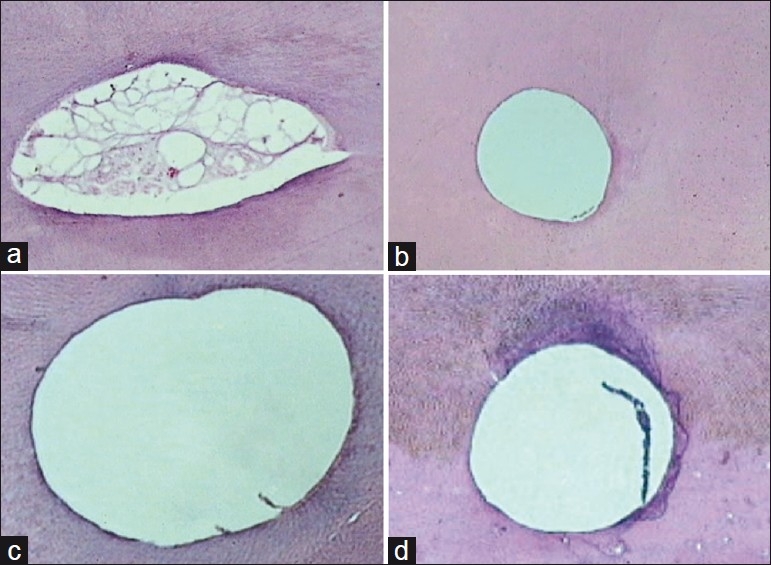

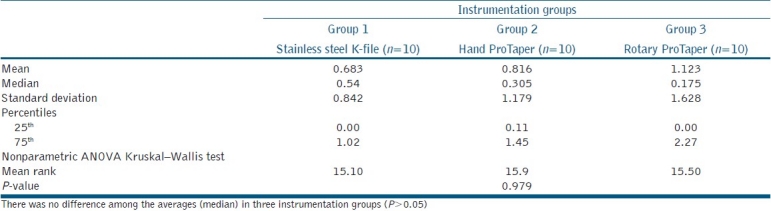

All the Instrumentation techniques were relatively efficient in debriding the apical one-third of the root canal system. The control group showed pulp remnants and unplaned walls [Figure 1a]. Stainless steel K-files showed the least amount of debris [Figure 1b], followed by hand ProTaper files [Figure 1c], and the group instrumented with rotary ProTaper files demonstrated maximum amount of debris [Figure 1d]. There were no statistically significant differences between the three experimental groups [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Histological picture of (a) control group; (b) group 1 (stainless steel K-file); (c) group 2 (hand ProTaper); and (d) group 3 (rotary ProTaper)

Table 1.

Mean, median, standard deviation, 25th percentile and 75th percentile of percentage of debris, mean rank in the three instrumentation groups and the P-value

DISCUSSION

All the instrumentations of the pulp space leave debris in the root canal.[3,6,7] This debris increases the risk of bacterial contamination which may lead to the failure of endodontic treatment.[8] Debris may be compacted along the entire length of the canal surface and results in reduced adaptation of sealer and gutta-percha.

Considering the major objective of the present investigation, irrigation was performed with distilled water, avoiding any associations of different irrigation solutions.

All the three groups failed to produce completely clean canals. This is in accordance with other studies which were performed to evaluate the debriding ability of various instruments.[4,7,9–13]

In addition, it was observed that some areas were uninstrumented, indicating that complete canal instrumentation was not achieved. Moreover, an irregular secondary dentine is associated with the physiological aging of the root[14] so that surface morphology, especially in the apical region, is far from smooth.[9] This could contribute to higher debris scores in the apical third of the canal.

Histological evaluation revealed that stainless steel K-files showed better cleaning efficiency with the least amount of debris, followed by hand ProTaper files, and ProTaper rotary files were least effective with maximum amount of debris. The results indicated that manual instrumentation appeared superior to rotary instrumentation for the debridement in the apical third of the root canal system, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. This observation is in agreement with that of other studies.[9,12,15]

F2 and F3 are more inflexible as compared to F1 which is of great clinical importance because leaving the file (rotary) in the canal for longer than 1 second can result in increased cutting of the apical portion[16] and hence increased debris formation. With the new ProTaper Universal manual and rotary F3 files, a U-shaped groove has been incorporated in the middle of each side of the convex triangular design to increase its flexibility in the apical third.[17] The use of F3 files resulted in better canal shape and less uninstrumented canal walls, but may have resulted in increasing the debris within the canal.[16]

The group instrumented with stainless steel K-files produced the least amount of debris [Figure 2], which could be attributed to the 0.02 taper. Lumley P. J. suggested that 0.02 taper instruments allow greater apical debridement when compared to greater taper instruments. When instrumentation is performed with files of greater taper, a false sense of tightness is created due to coronal binding of the flutes, but the apical part of the file may be lying passively within the canal.[18]

Figure 2.

Box-and-Whisker plot of percentages of debris in the three instrumentation groups

Enlargement of wide canals using ProTaper files resulted in 43–49% uninstrumented canal walls.[19] ProTaper instruments have multiple and progressively changing tapers along the length of their cutting blades, which reduce the contact area between the dentin and the file.[20] This may have resulted in less area of the walls planed and greater debris scores.

Debris area measurements were slightly greater for the canals instrumented with NiTi instruments. NiTi rotary instruments, due to their superelastic property, are not suitable for exertion of lateral pressure, therefore leaving many areas untouched by the instrument in oval shaped canals. Stainless steel instruments are stiffer than NiTi instruments and can be easily forced with less risk toward the root canal walls and the polar recesses following the natural canal shape and prepare the root canal walls.[7]

High debris in group 2 as compared to group 1 could be attributed to the aggressive nature of the ProTaper finishing files, although the results were not statistically significant.

Better cleaning efficiency of hand instrumentation may be due to the fact that increased number of rotations in apical one third is produced with rotary as compared to manual technique which may also have resulted in increased debris with rotary technique.

When an instrument is engaged toward its apical extent, greater torsional forces exist because of the distance between the torque generator (handle) and the resulting working torque at the apical extent of the file.[20] Torque controlled handpiece autoreverses in the canal when it binds in the apical one third and begins to rotate backward the standard two revolutions and then reverts to the original direction of rotation. It is important to be aware of this occurrence to remove the file from the tooth to clean the debris from the flutes.[21] This may be attributable to the deposition of debris in the apical one third.

It was our impression that the rotary instrumentation with ProTaper files was less time consuming, followed by hand ProTaper files and stainless steel K-files, respectively. This is beneficial for cleaning of the root canal, increasing the time of contact between the irrigants and their substrate.[22] It has to be taken into consideration that the cleaning efficiency of the different instruments might be further improved using a combination of NaOCl and EDTA solutions.

Apart from instrumentation and instrumentation techniques, other factors such as amount of root canal wall, irrigating regimens and curvature of the canal play a significant role in cleaning and shaping. Factors to be considered for the selection of instruments should be based on speed and ease of use, canal shaping ability, reduced apical transportation and the reliability of instrument under mechanical stress. The choice between manual, rotary and combination instrumentation techniques has to be made by the operator on a case to case basis, avoiding a generalized protocol.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hulsmann M, Rümmelin C, Schäfers F. Root canal cleanliness after preparation with different endodontic handpieces and hand instruments: A comparative SEM investigation. J Endod. 1997;23:301–6. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siqueira JF, Jr, Araujo MC, Garcia PF, Fraga RC, Dantas CJ. Histological evaluation of the effectiveness of five instrumentation techniques for cleaning the apical third of root canals. J Endod. 1997;23:499–502. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahlquist M, Henningsson O, Hultenby K, Ohlin J. The effectiveness of manual and rotary techniques in the cleaning of root canals: A scanning electron microscopy study. Int Endod J. 2001;34:533–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2001.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gambarini G, Laszkiewicz J. A scanning electron microscopic study of debris and smear layer remaining following use of GT rotary instruments. Int Endod J. 2002;35:422–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hülsmann M, Stryga F. Comparison of root canal preparation using different automated devices and hand instrumentation. J Endod. 1993;19:141–5. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80509-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heard F, Walton RE. Scanning electron microscope study comparing four root canal preparation techniques in small curved canals. Int Endod J. 1997;30:323–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1997.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbizam JVB, Fariniuk LF, Marchesan MA, Pecora JD, Sousa-Neto MD. Effectiveness of manual and rotary instrumentation techniques for cleaning flattened root canals. J Endod. 2002;28:365–6. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200205000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair NR, Sjögren U, Krey G, Kahnberg KE, Sundqvist G. Intraradicular bacteria and fungi in root filled, asymptomatic human teeth with therapy-resistant periapical lesions: A long-term light and electron microscopic follow-up study. J Endod. 1990;16:580–8. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(07)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bechelli C, Zecchi Orlandini S, Colafranceschi M. Scanning electron microscopic study on the efficacy of root canal wall debridement of hand versus Lightspeed instrumentation. Int Endod J. 1999;32:484–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1999.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foschi F, Nucci C, Montebugnoli L, Marchioni S, Breschi L, Malagnino VA, et al. SEM evaluation of canal wall dentine following use of Mtwo and ProTaper NiTi rotary instruments. Int Endod J. 2004;37:832–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schafer E, Vlassis M. Comparative investigation of two rotary nickel-titanium instruments: ProTaper versus RaCe. Part 1. Shaping ability in simulated curved canals. Int Endod J. 2004;37:239–48. doi: 10.1111/j.0143-2885.2004.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schafer E, Lohmann D. Efficiency of rotary nickel-titanium FlexMaster instruments compared with stainless steel hand K-Flexofile—Part 2. Cleaning effectiveness and instrumentation results in severely curved root canals of extracted teeth. Int Endod J. 2002;35:514–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schafer E, Schlingemann R. Efficiency of rotary nickel-titanium K3 instruments compared with stainless steel hand K-Flexofile. Part 2. Cleaning effectiveness and shaping ability in severely curved root canals of extracted teeth. Int Endod J. 2003;36:208–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakabayashi H, Matsumoto K, Nakamura Y, Shirasuka T. Morphology of the root canal wall and arrangement of underlying dentinal tubules. Int Endod J. 1993;26:153–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1993.tb00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kochis KA, Walton RE, Lilly JP, Ricks L, Rivera EM. A histologic comparison of hand and NiTi rotary instrumentation techniques. J Endod. 1998;24:286. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loizides AL, Kakavetsos D, Tzanetakis GN, Kontakiotis EG, Eliades G. A comparative study of the effects of two Nickel-Titanium preparation techniques on root canal geometry assessed by microcomputed tomography. J Endod. 2007;33:1455–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.West J. Progressive taper technology: Rationale and clinical technique for the new ProTaper Universal System. (66-9).Dent Today. 2006;25:64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lumley PJ. Cleaning efficacy of two apical preparation regimens following shaping with hand files of greater taper. Int Endod J. 2000;33:262–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2000.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters OA, Peters CI, Schonenberger K, Barbakow F. ProTaper rotary root canal preparation: Effects of canal anatomy on final shape analysed by micro CT. Int Endod J. 2003;36:86–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blum JY, Machtou P, Ruddle C, Micallef JP. Analysis of mechanical preparations in extracted teeth using ProTaper rotary instruments: Value of the safety quotient. J Endod. 2003;29:567–75. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200309000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suffridge CB, Hartwell GR, Walker TL. Cleaning efficiency of Nickel-Titanium GT and .04 rotary files when used in a torque-controlled rotary handpiece. J Endod. 2003;29:346–8. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200305000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasqualini D, Scotti N, Tamagnone L, Ellena F, Berutti E. Hand-operated and rotary ProTaper instruments: A comparison of working time and number of rotations in simulated root canals. J Endod. 2008;34:314–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]