Abstract

Motivation: Microbial community profiling is a highly active area of research, but tools that facilitate visualization of phylogenetic trees and associated environmental data have not kept up with the increasing quantity of data generated in these studies.

Results: TopiaryExplorer supports the visualization of very large phylogenetic trees, including features such as the automated coloring of branches by environmental data, manipulation of trees and incorporation of per-tip metadata (e.g. taxonomic labels).

Availability: http://topiaryexplorer.sourceforge.net

Contact: rob.knight@colorado.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

Microbial community profiling using marker genes such as the 16S rRNA greatly expanded our knowledge of the diversity of the microbial world (Tringe and Hugenholtz, 2008). Phylogenetic trees are key to our understanding of the microbial world (Pace, 1997), and provide an important view into microbial data (Ludwig et al., 2004). Software such as QIIME (Caporaso et al., 2010) has kept pace with the increasing rate of sequence acquisition to allow statistical analysis of these data, but tools to visualize and manipulate phylogenetic trees and corresponding metadata (Huson et al., 2007; Letunic and Bork, 2011; www.phylosoft.org/archaeopteryx; http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree), which worked well on datasets that were characteristic a few years ago, are less suitable for datasets containing millions of sequences.

A key question in microbial ecology is which portions of a phylogenetic reference tree are differentially represented in specific groups of samples. To address this question, users should be able to load trees with thousands of tips, assign taxonomic labels to the tips, and color the branches based on data about each sample.

Here we present TopiaryExplorer, a software package that facilitates visual exploration of large phylogenetic trees, including information about each sample and each tip. This integration of what is often called ‘sequence metadata’ is crucial to understanding how sequences (and their source organisms) are distributed across environments, and the processes underlying the observed patterns. TopiaryExplorer additionally allows display and revision of the taxonomy (including multiple taxonomies for the same tree, facilitating taxonomic comparisons), and integration with databases that contain sample/tree information (an example database is provided to assist users in creating their own: see below). It also provides key user interface improvements including: the ability to dynamically collapse or expand the whole tree using several different tree layout algorithms, allowing rapid visual exploration of which lineages are shared among or unique to specific subsets of environments; the ability to spawn new windows for investigation of specific subtrees and to view multiple trees at the same time; control over labels and layout features critical for producing publication-quality graphics; the ability to export results in any of several graphical and machine-readable formats for further analysis; and the ability to handle datasets of hundreds of thousands of tips, which can easily be created from larger datasets by OTU picking with UCLUST (Edgar, 2010) or related tools. TopiaryExplorer metadata is provided as tab-separated text, and trees are provided as Newick-formatted strings. These standard file formats allow data generated with different tools to be easily imported into TopiaryExplorer.

TopiaryExplorer is written in Java using Processing, which allows for rapid tree visualization and PDF export using OpenGL. The tree layout rendering algorithms in TopiaryExplorer were adapted from PyCogent (Knight et al., 2007). Several strategies were applied to efficiently visualize large trees and associated metadata, including caching node lookups rather than running multiple lookups of the same node, and using sparse table representations for storing and accessing metadata.

2 RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

To illustrate the utility of TopiaryExplorer we applied it to a microbial survey of the hands and keyboards of three individuals (Fierer et al., 2010). This study illustrated how individuals can be matched to objects they have touched through the use of ‘microbial fingerprints’. It has previously been difficult to identify the specific taxonomic differences between the hand or keyboard microbial communities from different individuals.

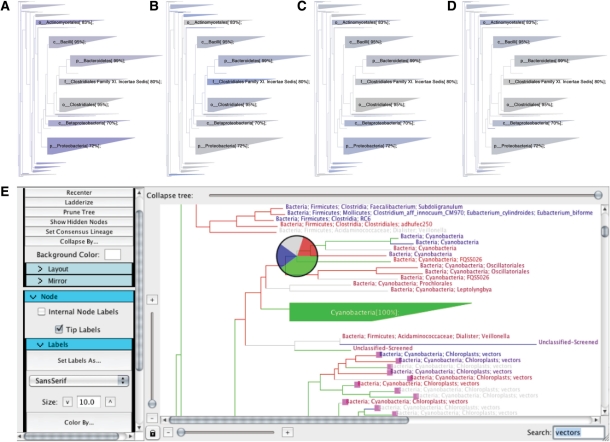

We applied TopiaryExplorer to specifically address this question and find that between-community taxonomic differences are present and easily discernable (Fig. 1A–D). The trees visually represent the results of the original study, that M3's keyboard is more similar to M3's fingertips than the fingertips of either M2 or M9, but additionally allows us to immediately determine which taxonomic groups are differentially represented in the different sample types. For example, M3's fingertips and keyboard contain Proteobacteria in higher abundance than M2 or M9. Figure 1E represents a screenshot of the TopiaryExplorer interface.

Fig. 1.

Coverage of samples over tree of 16S rRNA OTUs observed in this study. Wedges summarize groups of tips and colored on a gray to blue scale based on the abundance of tips in that wedge which are represented in the given sample type [(A) M3 (subject 3) keyboard, (B) M2 (subject 2) fingertips, (C) M3 fingertips, (D) M9 (subject 9) fingertips]. (E) TopiaryExplorer interface: branches are colored by individual (M2, M3, M9), tips labels are colored by source (specific keyboard key or fingertips), and the pie chart summarizes the representation of individuals in the clade. Pink boxes highlight tips matching the search term.

These results show how visual inspection of phylogenetic trees with environmental data can facilitate interpretation of the relative differences between microbial communities. TopiaryExplorer fills a necessary gap in tools for the comparison of microbial communities. The tree of life is being rapidly filled by large-scale projects such as Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea (GEBA), the Human Microbiome Project and the Earth Microbiome Project and annotated with emerging standards such as Minimum Information about any Sequence (MIxS). The ability to determine what lineages are novel in a new dataset, and what lineages distinguish among samples associated with clinical or environmental parameters, will be crucial for understanding the ecology and evolution of the microbes that comprise the vast majority of life on earth.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Cathy Lozupone, Jessica Metcalf, Laura Wegener Parfrey, Justin Kuczynski and Jose Clemente for feedback on this manuscript and TopiaryExplorer.

Funding: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; the National Institutes of Health (DK78669, HG4872 HG4866, 3T15LM009451-03S1); Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N, et al. Forensic identification using skin bacterial communities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:6477–6481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000162107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH, et al. Dendroscope: an interactive viewer for large phylogenetic trees. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:460. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R, et al. PyCogent: a toolkit for making sense from sequence. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R171. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life v2: online annotation and display of phylogenetic trees made easy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Suppl. 2):W475–W478. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig W, et al. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1363–1371. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace NR. A molecular view of microbial diversity and the biosphere. Science. 1997;276:734–740. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tringe SG, Hugenholtz P. A renaissance for the pioneering 16S rRNA gene. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008;11:442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]