Abstract

Intracellular Ca2+ plays a fundamental role in regulating cell functions in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs). A rise in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) triggers pulmonary vasoconstriction and stimulates PASMC proliferation. [Ca2+]cyt is increased mainly by Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and Ca2+ influx through plasmalemmal Ca2+-permeable channels. Given the high concentration of intracellular Cl- in PASMCs, Ca2+-activated Cl-(ClCa) channels play an important role in regulating membrane potential and cell excitability of PASMCs. In this study, we examined whether activity of ClCa channels was involved in regulating [Ca2+]cyt in human PASMCs via regulating receptor- (ROCE) and store- (SOCE) operated Ca2+ entry. The data demonstrated that an angiotensin II (100 nM)-mediated increase in [Ca2+]cyt via ROCE was markedly attenuated by the ClCa channel inhibitors, niflumic acid (100 μM), flufenamic acid (100 μM), and 4,4’-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2’-disulfonic acid (100 μM). The inhibition of ClCa channels by niflumic acid and flufenamic acid significantly reduced both transient and plateau phases of SOCE that was induced by passive depletion of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum by 10 μM cyclopiazonic acid. In addition, ROCE and SOCE were abolished by SKF-96365 (50 μM) and 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate (100 μM), and were slightly decreased in the presence of diltiazem (10 μM). The electrophysiological and immunocytochemical data indicate that ClCa currents were present and TMEM16A was functionally expressed in human PASMCs. The results from this study suggest that the function of ClCa channels, potentially formed by TMEM16A proteins, contributes to regulating [Ca2+]cyt by affecting ROCE and SOCE in human PASMCs.

Keywords: angiotensin II, Ca2+ signaling, Ca2+-activated Cl- current, niflumic acid, TMEM16A

INTRODUCTION

In pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) is mainly regulated by a balance of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and Ca2+ influx through plasmalemmal Ca2+-permeable channels, as well as Ca2+ sequestration into intracellular stores by the Ca2+-Mg2+ ATPase on the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum membrane (SERCA) and Ca2+ extrusion via the Ca2+-Mg2+ ATPase and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger on the plasma membrane.[1,2] PASMCs functionally express various Ca2+-permeable channels including (a) voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs) that are activated by membrane depolarization,[3] and (b) receptor-operated Ca2+ (ROC) channels that are stimulated and activated by vasoconstrictors, such as endothelin-1,[4] serotonin,[5] phenylephrine,[6] and histamine,[7] and by growth factors, including epidermal growth factor[8] and platelet-derived growth factor.[9] The activation of ROC channels by interaction between ligands and membrane receptors results in receptor-operated Ca2+ entry (ROCE) that greatly contributes to increases in [Ca2+]cyt in PASMCs exposed to vasoconstrictors and growth factors.[1,10,11] PASMCs also possess (c) store-operated Ca2+ (SOC) channels that are opened by the depletion of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), which leads to capacitative Ca2+ entry, or store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE). SOCE is an important mechanism involved in maintaining a sustained elevation of [Ca2+]cyt and refilling Ca2+ into the depleted SR.[1,10–12] We showed previously that increased Ca2+ influx through SOC or SOCE contributes to stimulating PASMC proliferation; inhibition of SOCE significantly attenuated growth factor-mediated PASMC proliferation. These results suggest that SOCE plays a significant role in regulating proliferation in vascular smooth muscle cells.[9,13,14]

It has been well demonstrated that the activity of Ca2+-activated Cl- (ClCa) channels play an important role in regulating contraction, migration, and apoptosis in many cell types.[15,16] In vascular smooth muscle cells, ClCa channels are activated by a rise in [Ca2+]cyt following agonist-induced Ca2+ release from the SR through inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs). In addition, the activation of ClCa channels is evoked by spontaneous Ca2+ release through ryanodine receptors in the SR and is responsible for eliciting spontaneous transient inward currents in several types of vascular smooth muscle cells. The intracellular Cl- concentration in vascular smooth muscle cells (including PASMCs) is estimated to be 30 to 60 mM,[15–17] so the reversal potential for Cl- is supposed to be much less negative (ranging from -20 to -30 mV) than that for K+ (approximately -80 mV). Therefore, an increase in Cl- conductance in PASMCs under these conditions would generate inward currents (due to Cl- efflux) and cause membrane depolarization which subsequently induces Ca2+ influx by opening VDCCs and ultimately results in vasoconstriction. The molecular composition of ClCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells (including PASMCs), however, is not fully identified. Recently, a transmembrane protein encoded by TMEM16A gene has been demonstrated to form ClCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells.[18–20]

In this study, we examined whether ClCa channel activity was involved in the regulation of [Ca2+]cyt via ROCE and SOCE in human PASMCs using digital imaging fluorescence microscopy. We also examined the functional expression of ClCa channels (TMEM16A) in human PASMCs using electrophysiological and immunocytochemical approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Human PASMCs (passage 5 to 10) from normal subjects were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD) Cells were cultured in Medium 199 (Invitrogen-GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen-GIBCO), 100 U/ml penicillin plus 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen-GIBCO), 50 μg/ml D-valine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 20 μg/ml endothelial cell growth supplement (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at 37°C. All cells were incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. After reaching confluence, the cells were sub-cultured by trypsinization with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen-GIBCO), plated onto 25-mm cover slips (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). and incubated at 37°C for 1-3 days before electrophysiological and fluorescence microscopy experiments.

[Ca2+]cyt measurement

Human PASMCs cultured on 25-mm cover slips were placed in a recording chamber on the stage of an invert fluorescent microscope (Eclipse Ti-E; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an objective lens (S Plan Fluor 20×/0.45 ELWD; Nikon) and an EM-CCD camera (Evolve; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). [Ca2+]cyt was monitored using a membrane-permeable Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent indicator, fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (fura-2/AM; Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and imaged with NIS Elements 3.2 software (Nikon). Cells were loaded by incubation in HEPES-buffered solution containing 4 μM fura-2/AM for 60 min. at room temperature (25°C). The loaded cells were then washed with HEPES-buffered solution for 10 min. to remove excess extracellular indicator and allow sufficient time for intracellular esterase to cleave acetoxymethyl ester from fura-2. Cells were then excited at 340-nm and 380-nm wavelengths (D340×v2 and D380×v2 filters, respectively; Chroma Technology, Bellows Falls, VT) by a xenon arc lamp (Lambda LS; Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA) and an optical filter changer (Lambda 10-B; Sutter Instrument). Emission of Fura-2 was collected through a dichroic mirror (400DCLP; Chroma Technology) and a wide band emission filter (D510/80m; Chroma Technology). [Ca2+]cyt within a region of interest (5×5 μm) that was placed at the peripheral region of each cell was measured as the ratio of fluorescence intensities (F340/F380) every 2 sec. The HEPES-buffered solution had an ionic composition of 137 mM NaCl, 5.9 mM KCl, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 14 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with 10 N NaOH. The external Ca2+-free solution was prepared by removing extracellular CaCl2 and adding 1 mM EGTA (to chelate the residual Ca2+ in the bath solution). The recording chamber was continuously perfused with HEPES-buffered solution at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. using a mini-pump (Model 3385; Control, Friendswood, TX). [Ca2+]cyt measurements were carried out at 32°C using an automatic temperature controller (TC-344B, Warner Instruments, Holliston, MA).

Electrophysiological recording

The whole-cell ClCa current in a single PASMC was recorded using the patch-clamp technique with an Axopatch-1D amplifier (Molecular Devices-Axon, Foster City, CA), an analog-digital converter (Digidata 1200; Molecular Devices-Axon), and pCLAMP 8 software (Molecular Devices-Axon). The extracellular (bath) solution had an ionic composition of 137 mM NaCl, 10 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA) chloride, 5 mM 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), 2.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 14 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with 10 N NaOH. The low Cl- concentration solution was prepared by substituting 117 mM NaCl of the extracellular solution with the equal molar of sodium gluconate. The pipette (intracellular) solution contained 120 mM CsCl, 20 mM TEA chloride, 4.3 mM CaCl2, 2.8 mM MgCl2, 2 mM Na2ATP, 10 mM HEPES, and 5 mM EGTA. The pCa was fixed to 6.0, which was estimated by the Maxchelator program (http://www.stanford.edu/~cpatton/maxc.html). The pH was adjusted to 7.2 with 1 N CsOH. The recording chamber was continuously superfused with extracellular solution at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. using a perfusion system (VC-6; Warner Instrument, Hamden, CT). Electrophysiological recordings were carried out at room temperature (25°C).

Immunocytochemical staining

Cultured cells on 35-mm culture dishes with 14-mm glass bottom (MatTek, Ashland, MA) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (DPBS; Invitrogen-GIBCO) for 10 min. at room temperature (25°C). Excessive paraformaldehyde was removed thoroughly with DPBS. The cells were then treated with DPBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100, 1% normal goat serum (Dako Denmark, Glostrup, Denmark), and TMEM16A antibody (pre-diluted, ab53213, Abcam, Cambridge, MA; or 1:100 dilution, ab53212, Abcam) for 12 hr. at 4°C. After washing repeatedly in DPBS, the cells were covered with DPBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100, 1% normal goat serum, and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibody (1:100 dilution; Invitrogen-Molecular Probes) for 1 hr. at room temperature and then rinsed with DPBS. Then cells were mounted in VECTASHIELD hard-set mounting medium with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1.5 μg/ml) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and placed on the stage of an invert fluorescent microscope (Eclipse Ti-E; Nikon) equipped with an objective lens (Plan Apo 60×/1.40 oil immersion; Nikon), a CCD camera (CoolSNAP ES2; Photometrics), and NIS Elements 3.2 software (Nikon). Immunocytochemical images were obtained using the specific filter sets for DAPI (Ex340-380/DM400/Em435-485; Chroma Technology) and Alexa Fluor 488 (Ex460500/DM505/Em510-560; Chroma Technology).

Drugs

Pharmacological reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. All hydrophobic compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at the concentration of 10 or 100 mM as a stock solution. It was confirmed that up to 0.1 % of DMSO did not affect these responses.

Statistical analysis

Pooled data are shown as the mean±SE. The statistical significance between two groups was determined by Student's t-test. The statistical significance among groups was determined by Scheffé's test after one-way analysis of variance. Significant difference is expressed in the figures as *P<0.05 or **P<0.01.

RESULTS

Inhibition of agonist-induced Ca2+ influx or ROCE by ClCa channel blockers in human PASMCs

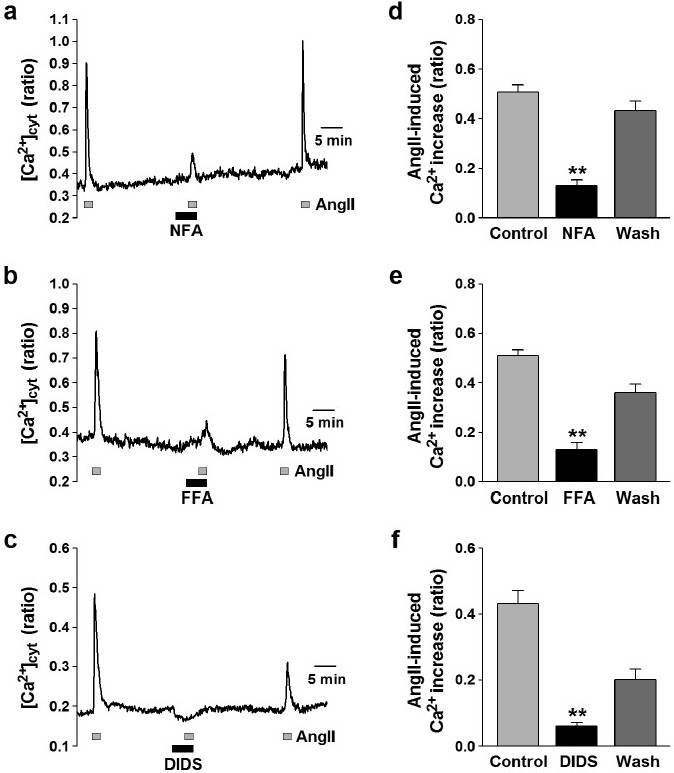

The increase in [Ca2+]cyt evoked by agonist stimulation was imaged in human PASMCs loaded with 4 μM fura-2/AM and quantitated in arbitrary units (au) by the change in F340/F380 ratio. Short-term application (2 min.) of 100 nM angiotensin II induced a transient increase in [Ca2+]cyt (by 0.49±0.01 au, n=150) (Figs. 1 and 2). The angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase was attenuated by 100 μM niflumic acid, a fenamate compound that is most frequently used as a blocker of ClCa channels (from 0.51±0.03 to 0.13±0.02 au, n=29, P<0.01) (Fig. 1a and d). The inhibitory effect of niflumic acid on the angiotensin II-mediated increase in [Ca2+]cyt was reversible upon washout (0.42±0.04 au, n=29). Pretreatment with 100 μM flufenamic acid, another fenamate compound that blocks ClCa channels, markedly reduced the angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase (from 0.51±0.02 to 0.13±0.03 au, n=33, P<0.01) (Fig. 1b and e). A different type of Cl- channel blocker, 4,4’-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2’-disulfonic acid (DIDS)-one of the stilbene derivatives that is structurally unrelated to fenamates–also caused a significant inhibition of the angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase (from 0.43±0.04 to 0.06±0.01 au, n=18, P<0.01) (Fig. 1c and f). These data indicated that the function of ClCa channels is involved in regulating ROCE in human PASMCs; inhibition of ClCa channels significantly and reversibly attenuates the agonist-mediated Ca2+ entry.

Figure 1.

Attenuation of ROCE by ClCa channel blockers in human PASMCs. Angiotensin II (AngII, 100 nM) was used to induce ROCE in human PASMCs. (a-c) Representative traces showing angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt increases in human PASMCs before, during, and after application of 100 μM niflumic acid (NFA; a), flufenamic acid (FFA; b), and DIDS (c). Blockage of ClCa channels reduces angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevation in human PASMCs. (d-f) Summarized data showing the reversible inhibitory effects of niflumic acid (d), flufenamic acid (e), and DIDS (f) on angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt rises in human PASMCs. Statistical significance (versus control) is indicated as **P<0.01.

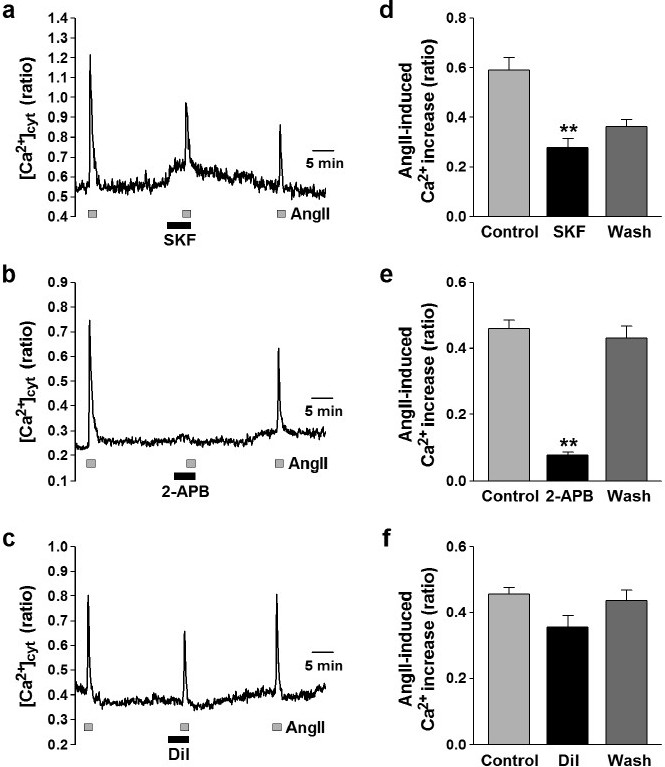

Figure 2.

Effects of Ca2+ channel blockers on ROCE in human PASMCs. Angiotensin II (AngII, 100 nM) was used to induce ROCE in human PASMCs. (a-c) Representative traces showing angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt rises in human PASMCs before, during, and after application of 50 μM SKF-96365 (SKF, an inhibitor of nonselective cation channels; a), 100 μM 2-APB (which blocks IP3Rs and also non-selective cation channels; b), and 10 μM diltiazem (a VDCC blocker; c). (d-f) Summarized data showing effects of SKF-96365 (d), 2-APB (e), and diltiazem (f) on angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase in human PASMCs. Statistical significance (versus control) is indicated as **P<0.01.

Effects of Ca2+ channel blockers on ROCE in human PASMCs

To elucidate the Ca2+ signal pathway for angiotensin II-induced ROCE, effects of the inhibitors for several different types of Ca2+ channels were examined in human PASMCs. The angiotensin II-mediated increase in [Ca2+]cyt was reduced by treatment with 50 μM SKF-96365, an inhibitor of non-selective cation channels (from 0.59±0.05 to 0.28±0.04 au, n=13, P<0.01) (Fig. 2a and d). The application of 100 μM 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate (2-APB), which blocks IP3 Rs and also non-selective cation channels, abolished the angiotensin II-induced increase in [Ca2+]cyt (from 0.46±0.03 to 0.08±0.01 au, n=22, P<0.01) (Fig. 2 b and e). Blockage of VDCC with 10 μM diltiazem, however, had a trend to inhibit the angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase (from 0.45±0.02 to 0.36±0.03 au, n=35, P>0.05 by Scheffé's test, but P<0.01 by Student's t-test) (Fig. 2 c and f). These pharmacological data indicate that the angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase was mainly caused by Ca2+ release from the SR through IP3R followed by Ca2+ influx via non-selective cation channels in human PASMCs. Ca2+ influx through the diltiazem-sensitive L-type VDCCs slightly contributes to the angiotensin II-induced rise of [Ca2+]cyt in human PASMCs.

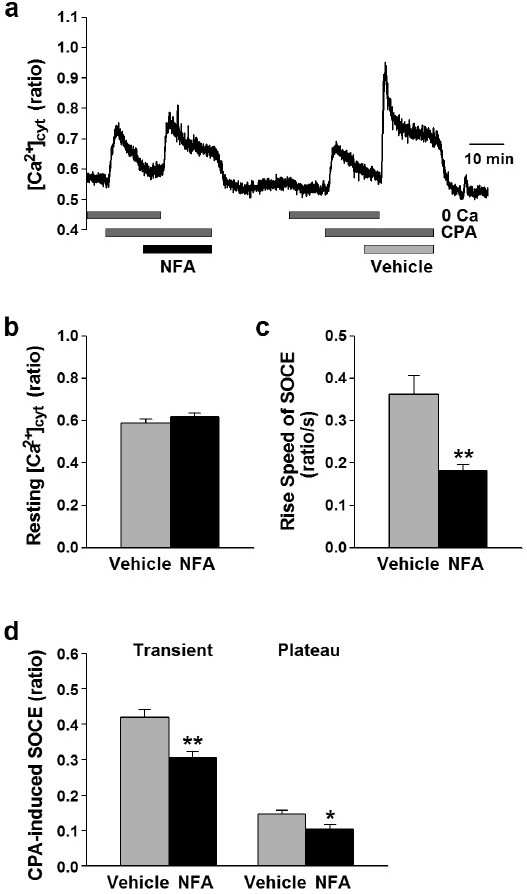

Inhibitory effect of ClCa channel blockers on SOCE in human PASMCs

In the next set of experiments, we examined the effect of ClCa channel blockers on SOCE in human PASMCs (Fig. 3). SOCE was induced by passive depletion of Ca2+ from the SR with 10 μM cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), a blocker of SERCA. In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, application of CPA induced a transient increase in [Ca2+]cyt that was due predominantly to Ca2+ leakage from the SR to the cytosol. Restoration of extracellular Ca2+ after approximately 10 min. treatment with CPA caused another increase in [Ca2+]cyt that was apparently due to Ca2+ influx through store-operated cation (or Ca2+) channels or SOCE.

Figure 3.

Attenuation of SOCE by ClCa channel blocker in human PASMCs. SOCE was induced by passive depletion of Ca2+ from the SR with 10 μM CPA in human PASMCs. (a) Typical trace of CPA-induced Ca2+ release and SOCE in the absence (vehicle, 0.1% DMSO) and presence of 100 μM niflumic acid (NFA) in a human PASMC. Blockage of ClCa channels caused a reduction of SOCE in human PASMCs. (b-d) Summarized data showing effects of niflumic acid on the resting [Ca2+]cyt (b), the rise speed of SOCE (c), the transient and plateau amplitudes of CPA-induced SOCE (d) in human PASMCs. Statistical significance versus vehicle control is indicated as *P<0.05 or *<0.01.

As shown in Figure 3, there were no significant differences in the resting [Ca2+]cyt (0.59±0.02 versus 0.62±0.02 au, n=55, P=0.25) and the amplitude of the increase in [Ca2+]cyt due to CPA-induced Ca2+ leakage from the SR to the cytosol when cells were treated with 100 μM niflumic acid or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) (Fig. 3 a and b). The transient and plateau phases of CPA-induced increases in [Ca2+]cyt due to SOCE, as well as the amplitude and “rise-speed” of SOCE were all significantly decreased by 100 μM niflumic acid. The rise-speed of SOCE in the presence of niflumic acid (0.18±0.01 ratio/s, n=55) was significantly slower than that in the absence (0.36±0.04 ratio/s, P<0.01 (Fig. 3c). In addition, application of niflumic acid significantly reduced the amplitude of the transient (from 0.42±0.02 to 0.31±0.02 au, n=55; P<0.01) and plateau (from 0.15±0.01 to 0.10±0.01 au, n=55; P=0.02) phases of SOCE (Fig. 3a and d). Treatment of the cells with 100 μM flufenamic acid also significantly decreased the amplitude of the transient and plateau phases of CPA-induced SOCE in human PASMCs (n=34). These data clearly suggest that the activity of ClCa channels is involved in regulating SOCE in human PASMCs.

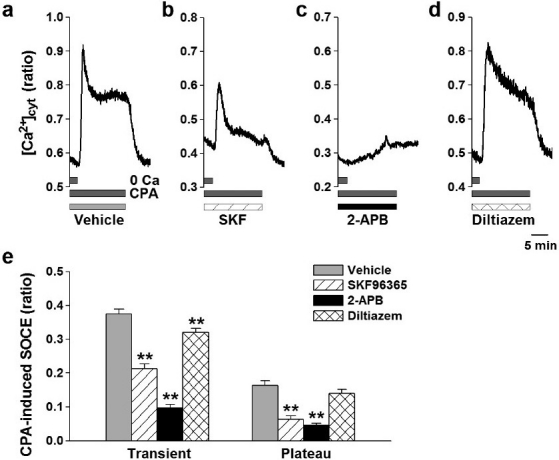

Effects of Ca2+ channel blockers on SOCE in human PASMCs

To functionally define the Ca2+ channels responsible for CPA-mediated SOCE, we examined the effects of different Ca2+ channel blockers on SOCE in human PASMCs. The transient component of CPA-induced SOCE was significantly reduced by 50 μM SKF-96365 (0.21±0.01 au, n=51, versus vehicle control, 0.37±0.01 au, n=58; P<0.01) (Fig. 4 a, b and e) and 100 μM 2-APB (0.10±0.01 au, n=46, P<0.01) (Fig. 4 c and e). Application of 10 μM diltiazem slightly (but significantly) affected the transient component of SOCE (from 0.37±0.01 to 0.32±0.01 au, n=42, P<0.01), but had no effect on the plateau phase of SOCE (from 0.16±0.01 au, n=58, to 0.14±0.01 au, n=42, P=0.22) (Fig. 4 a, d and e). Similar to their effects on the transient phase of SOCE, 50 μM SKF-96365 (from 0.16±0.01, n=58, to 0.06±0.01 au, n=51; P<0.01) (Fig. 4a, b and e) or 100 μ 2-APB (to 0.05±0.01 au, n=46, P<0.01) (Fig. 4c and e) also significantly reduced the plateau phase of CPA-induced SOCE. These pharmacological data indicate that the Ca2+ signaling pathway for CPA-induced SOCE was mainly dependent on Ca2+ influx through non-selective cation channels in human PASMCs. The activity of VDCCs might be, in part, involved in the Ca2+ influx pathway in human PASMCs.

Figure 4.

Effects of Ca2+ channel blockers on SOCE in human PASMCs. SOCE was induced by passive depletion of Ca2+ from the SR with 10 μM CPA in human PASMCs. (a-d) Typical traces showing CPA-induced Ca2+ release and SOCE in the absence (vehicle, 0.1% DMSO; a) and presence of 50 μM SKF-96365 (SKF, a blocker for non-selective cation channels; b), 100 μM 2-APB (a blocker of IP3Rs and non-selective cation channels; c), and 10 μM diltiazem (an inhibitor of VDCCs; d) in human PASMCs. (e) Summarized data showing effects of Ca2+ channel blockers on the transient and plateau amplitudes of CPA-induced SOCE in human PASMCs. The number of cells examined is given in parentheses. Statistical significance versus vehicle control is indicated as **P<0.01.

Whole-cell ClCa currents in human PASMCs

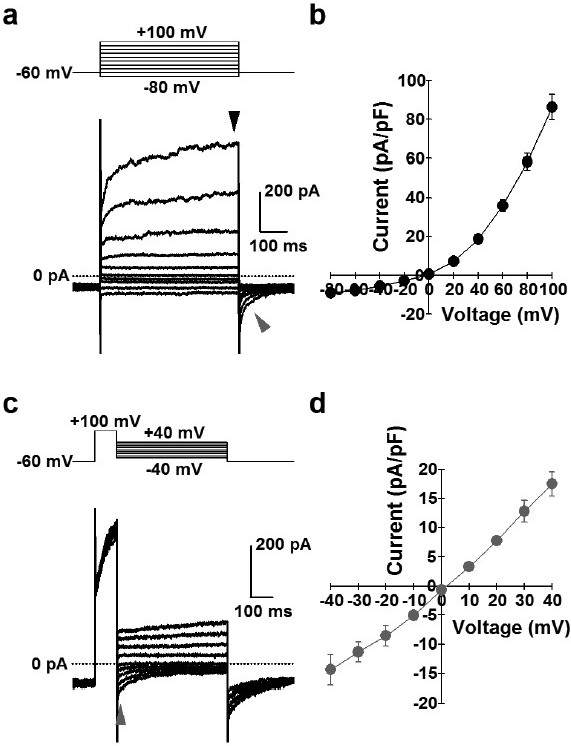

Electrophysiological and pharmacological properties of ClCa currents in human PASMCs were analyzed by whole-cell patch-clamp configuration using a pipette (intracellular) solution containing 120 mM Cs+, 20 mM TEA (pCa=6.0) and a bath (extracellular) solution containing 10 mM TEA and 5 mM 4-AP. The mean cell-capacitance was 9.0±1.2 pF (n=14). Depolarizing pulses (500 ms) were applied from a holding potential of -60 mV to a series of test potentials ranging from -80 to +100 mV by 20-mV increments every 15 sec. Outward currents were elicited by depolarization from the holding potential to the positive potentials above 0 mV, and the averaged current density at +100 mV was 86±7 pA/pF (n=14) (Fig. 5 a and b). The reversal potential of the whole-cell currents was -3.4±1.3 mV (n=14) (Fig. 5b), which is close to the theoretical (or calculated) equilibrium potential of Cl- (+0.1 mV). In addition, the reversal potential was shifted positively (to the right) by approximately 30 mV (positive shift by 36 mV in theory) by changing the extracellular Cl- concentration from 153.8 to 36.8 mM (data not shown). Importantly, we were able to detect inward “tail” currents when cells were repolarized to the holding potential (Fig. 5a), which is an important characteristic of ClCa currents. Furthermore, we analyzed the tail currents and the current-voltage relationship using the pulse protocol as follows: depolarizing pre-pulses were applied from a holding potential of -60 to +100 mV for 100 ms and subsequently test pulses were applied between -40 to +40 mV by 10-mV increments for 500 ms every 15 sec. (Fig. 5c). The current-voltage relationship revealed that the reversal potential of the tail currents (1.9±0.9 mV, n=4; Fig. 5d) was also very close to the theoretical (or calculated) equilibrium potential of Cl-.

Figure 5.

Whole-cell ClCa currents in human PASMCs. ClCa currents were measured using a pipette solution containing 120 mM Cs+, 20 mM TEA and pCa 6.0, and a bath solution containing 10 mM TEA and 5 mM 4-AP in human PASMCs. (a) Representative outward currents (black arrowhead), elicited by depolarization from a holding potential of -60 mV to a series of test potentials (-80 to +100 mV) for 500 ms every 15 sec. and inward tail currents (gray arrowhead), induced by repolarization to -60 mV in a human PASMC. (b) I-V relationship at peak amplitude during depolarization (black arrowhead in “a”). The current reverses at about 0 mV, the theoretical equilibrium potential of Cl-. (c) Representative tail currents (gray arrowhead) at a series of test potentials (-40 to +40 mV) for 500 ms after depolarization from a holding potential of -60 to +100 mV for 100 ms every 15 sec. in a human PASMC. (d) I-V relationship of tail currents (gray arrowhead in “c”). The reversal potential is close to 0 mV.

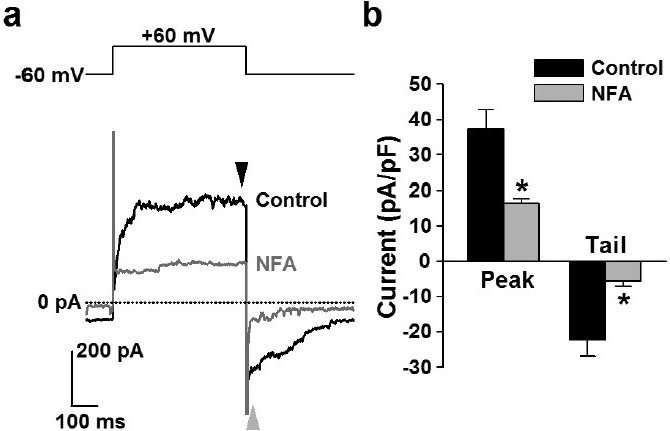

Application of 100 μM niflumic acid significantly attenuated both the outward ClCa current and the inward tail current in human PASMCs (Fig. 6). Niflumic acid decreased the outward currents elicited by depolarization from a holding potential of -60 to +60 mV (for 500 ms every 15 s) (from 37.4±5.3 to 16.5±1.2 pA/pF, n=3; P=0.046). The inward tail currents were also inhibited by the pretreatment with niflumic acid (-5.6±1.3 pA/pF, n=3, versus control of -22.2±4.7 pA/pF, P=0.040). These electrophysiological data indicate that ClCa channels sensitive to niflumic acid are functionally expressed in human PASMCs.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of ClCa currents by niflumic acid in human PASMCs. Effect of niflumic acid on whole-cell ClCa currents was examined in human PASMCs. (a) Representative outward currents (black arrowhead), elicited by depolarization from a holding potential of -60 to +60 mV, and inward tail currents (gray arrowhead), induced by repolarization to -60 mV in the absence (black line) and presence (gray line) of 100 μM niflumic acid (NFA) in a human PASMC. (b) Summarized data showing the effect of niflumic acid on outward (black arrowhead in “a”) and tail (gray arrowhead in “a”) currents in human PASMCs. The number of cells examined is given in parentheses. Statistical significance versus control is indicated as *P<0.05.

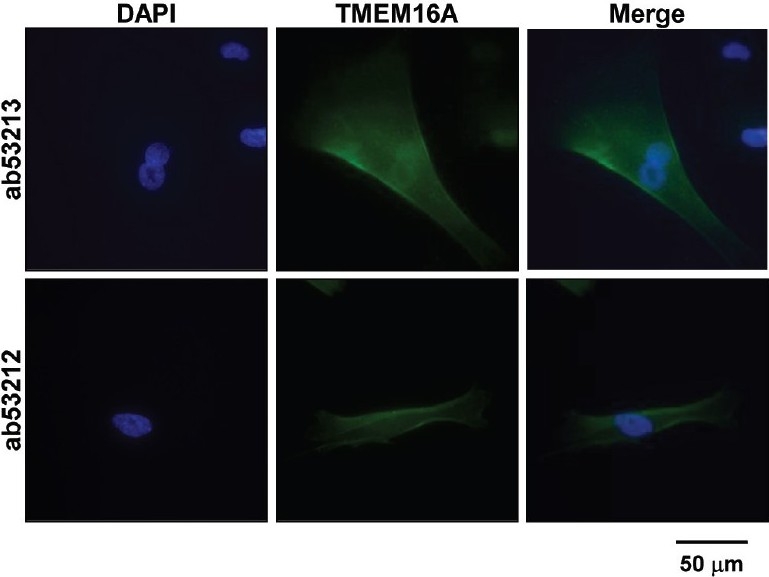

Expression of TMEM16A in human PASMCs

The molecular basis of ClCa channels in human PASMCs was identified by an immunocytochemical approach using two specific primary antibodies of TMEM16A (ab53213 and ab53212 from Abcam), a potential protein candidate for ClCa channels. Immunocytochemical experiments (Fig. 7) revealed that specific fluorescent signals of TMEM16A protein were localized in the cell membrane. Qualitatively, the same images were obtained from 3 separate sets of experiments. This result indicates that the activity of ClCa channels in human PASMCs is potentially due to channels formed by TMEM16A.

Figure 7.

Expression of TMEM16A in human PASMCs. Immunocytochemical analysis of TMEM16A, a potential candidate for the ClCa channel subunit, was performed in human PASMCs using two specific primary antibodies (ab53213 and ab53212 from Abcam). Alexa Fluor 488 and DAPI were used as a secondary antibody and a nuclear marker, respectively. Specific signals of TMEM16A protein were detected on the plasma membranes of human PASMCs. Similar immunocytochemical images were obtained from 3 sets of independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In vascular smooth muscle cells, ClCa channels are present for diverse physiological and pathological functions. In this study, we showed that the blockage of ClCa channels using pharmacological tools markedly attenuated both ROCE and SOCE in human PASMCs. Our electrophysiological and immunocytochemical data also indicated that the activity of ClCa channels functionally expressed in human PASMCs was due potentially to channels formed by TMEM16A proteins.

Intracellular free Ca2+ plays an important role in the regulation of contraction, proliferation, and migration of PASMCs. An increase in [Ca2+]cyt in PASMCs is a major trigger for pulmonary vasoconstriction and an important stimulus for PASMC proliferation that leads to pulmonary vascular remodeling under pathological conditions. Elevation of [Ca2+]cyt in PASMCs results from Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, such as the SR, and Ca2+ influx through plasmalemmal Ca2+ channels, such as ROC channels, SOC channels, and VDCCs.[1,2]

Angiotensin II is a vasoconstrictor that is commonly used for eliciting agonist-induced [Ca2+]cyt rises in PASMCs and other vascular smooth muscle cells.[21,22] In this study, we used angiotensin II to induce ROCE because, at the concentration of 100 nM, it caused an increase in [Ca2+]cyt in a large number of human PASMCs (>70%). The angiotensin II-mediated increase in [Ca2+]cyt via ROCE was markedly reduced by two different types of ClCa channel inhibitors, fenamates (niflumic acid and flufenamic acid) and one of the stilbene derivatives (DIDS). Both niflumic acid and flufenamic acid are well known fenamates that are most frequently used as ClCa channel blockers in electrophysiological and pharmacological studies. However, these compounds have been reported to also act on other types of ion channels such as non-selective cation channels,[23] large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels,[24] and transient receptor potential canonical subfamily (TRPC) channels.[25] Therefore, to confirm whether or not the inhibitory effects of niflumic acid and flufenamic acid on the angiotensin II-evoked increase in [Ca2+]cyt in human PASMCs were mediated by the blockage of ClCa channels, we analyzed the effects of another type of ClCa channel blocker, DIDS, a stilbene derivative that is structurally unrelated to fenamates, on the angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase. Similar to niflumic acid and flufenamic acid, DIDS also significantly suppressed the angiotensin II-induced [Ca2+]cyt increase, although it might have interfered with the fura-2 fluorescence due to its faint yellow colored solution at a concentration of 100 μM. These results, by using two different types of ClCa channel blockers, strongly suggest that the function of ClCa channels is involved in regulating ROCE in human PASMCs.

SOCE is essential for maintaining a high level of [Ca2+]cyt and for refilling intracellular Ca2+ stores (i.e., SR) in smooth muscle cells.[1,10–12] High levels of [Ca2+]cyt and sufficient levels of Ca2+ in the SR are required for proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells.[1,10] SOCE is enhanced while SOC channels are upregulated during PASMC proliferation to increase Ca2+ influx and provide sufficient Ca2+ for activation of the intracellular mechanisms responsible for cell proliferation and growth.[9,13,14] In the present study, we demonstrated that the blockage of ClCa channels by niflumic acid and flufenamic acid reduced both the transient and plateau components of SOCE as well as the rise speed of SOCE in human PASMCs. These data indicate that the function of ClCa channels is also involved in regulating SOCE in human PASMCs (in addition to the effect on ROCE). Suppression of SOCE by blockage of ClCa channels is thought to cause reduced PASMC proliferation, which may be a novel strategy for preventing the abnormal proliferation under pathological conditions. TRPC channels have been demonstrated to be involved in agonist- or growth factor-mediated Ca2+ entry in PASMCs,[1,10,26] while functional coupling of stromal interaction molecule (STIM) proteins (STIM1 and STIM2) with TRPC and/or Orai channels have recently been suggested as a novel candidate for SOC channel subunits in PASMCs.[27–29] TRPC channel genes are thought to encode pore-forming subunits that compose ROC[30–32] and SOC[33–35] channels in many cell types of vascular smooth muscles including PASMCs.[9,13,14,36–38] Ca2+ entry via ROC and SOC channels is modulated by second messengers, phosphorylation of signal transduction proteins, and transcription factors.[2,10,39] The protein expression levels of TRPC, STIM and Orai are changed under pathological conditions such as in pulmonary arterial hypertension.[1,10,39]

Smooth muscle cells contain a high concentration of Cl- in the intracellular space, which is considerably different from other cell types, such as neurons, cardiomyocytes, and skeletal muscle myocytes.[17] Therefore, increases in Cl- conductance across the plasma membrane (e.g., as a result of activation of ClCa channels when [Ca2+]cyt is increased) lead to Cl- efflux and inward currents, which consequently causes membrane depolarization, enhanced Ca2+ influx through VDCCs, increased [Ca2+]cyt, and vasoconstri-ction.[15,16] In the present study, electrophysiological data indicated that ClCa channels were functionally expressed in human PASMCs and the Cl- currents through ClCa channels were sensitive to niflumic acid. The electrophysiological properties (e.g., the time-dependent outward current during membrane depolarization, the inward tail current during repolarization, the outward rectification, and the shift of reversal potential based on the change in extracellular Cl- concentration) and pharmacological properties (e.g., the dependency on intracellular Ca2+ concentration and the sensitivity to niflumic acid) of whole-cell ClCa currents obtained from human PASMCs were consistent with the same properties reported previously in PASMCs from rabbits[40] and rats.[41,42] The [Ca2+]cyt increase mediated by ROCE and SOCE also activates the ClCa channels, resulting in membrane depolarization followed by additional Ca2+ influx through VDCCs. Slight decreases in ROCE and SOCE by diltiazem, a VDCC blocker, suggested that VDCCs only partly contributed to the regulation of ROCE and SOCE, although the Ca2+ influx pathway was mainly due to non-selective Ca2+ channels sensitive to SKF-96365 and 2-APB in human PASMCs.

ClCa channels play important roles in diverse functions in vascular smooth muscle cells. In spite of its physiological and pathological significances, the molecular architecture of ClCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells has not been clearly demonstrated. More recently, the TMEM16 family, consisting of 10 genes in mammals, has been found as a novel candidate for ClCa channel subunits.[18–20,43] Heterologous expression of TMEM16A has been shown to generate Cl- currents sensitive to intracellular Ca2+ and with the degree of outward rectification, ion selectivity, and pharmacological profile[18–20] similar to the activity of native ClCa channels observed in many tissues containing interstitial cells of Cajal in gastrointestinal muscles,[44–46] airway epithelial cells,[47,48] as well as vascular smooth muscle cells.[42,49] The distribution pattern of TMEM16A in interstitial cells of Cajal in gastrointestinal muscles,[44–46,50] airway epithelial cells,[47,48] and vascular smooth muscle cells[49] implies the functional expression of ClCa conductance. In this study, TMEM16A protein was localized in the plasma membrane of human PASMCs, indicating that the activity of the ClCa channel in human PASMCs was, at least in part, due to channels formed by TMEM16A. It has been reported that the TMEM16A gene also has some splice variants[18,42,49,51] and TMEM16B, a closely related analogue, also can generate Cl- currents activated by Ca2+.[19,52–54] It is unclear whether TMEM16B is another subunit that forms ClCa channels in human PASMCs.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension is a fatal and progressive disease characterized pathologically by severe pulmonary vascular remodeling. A central aspect of pulmonary vascular remodeling is adventitial, medial, and intimal hypertrophy caused by excessive proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in the adventitia, PASMCs in the media and endothelial cells in the intima. The concentric pulmonary vascular wall remodeling or thickened arterial and arteriole wall, narrows the intra-arterial lumen, increases pulmonary vascular resistance and ultimately causes pulmonary hypertension.[2,39] Since SOC and ROC channels are upregulated in PASMC isolated from patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) and from animals with hypoxia-mediated pulmonary hypertension, Ca2+ entry through these upregulated cation channels may play an important pathogenic role in the initiation and progression of pulmonary vascular remodeling under the pathological conditions.[1,10,14,26,28,37] It remains unclear, however, whether the activity of ClCa channels is also involved in the sustained pulmonary vasoconstriction and excessive pulmonary vascular remodeling in patients with IPAH and animals with hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Based on the observations from this study, the attenuation of SOCE and ROCE by ClCa channel blockers (e.g., niflumic acid, flufenamic acid, and DIDS) may serve as a potential therapeutic approach for pulmonary vascular disease. Although it is suggested that Cl- channels are involved in SOCE and proliferation in PASMCs,[55,56] further experiments are necessary to elucidate the mechanism underlying the regulation of ROCE and SOCE by ClCa channels in human PASMCs.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This work was supported, in part, by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (HL066012 and HL098053 to JX-JY)

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Firth AL, Remillard CV, Yuan JX. TRP channels in hypertension. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrell NW, Adnot S, Archer SL, Dupuis J, Jones PL, MacLean MR, et al. Cellular and molecular basis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:S20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Firth AL, Remillard CV, Platoshyn O, Fantozzi I, Ko EA, Yuan JX. Functional ion channels in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells: Voltage-dependent cation channels. Pulm Circ. 2011;1:48–71. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.78103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT, Sham JS. Inhibition of voltage-gated K+ current in rat intrapulmonary arterial myocytes by endothelin-1. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L842–53. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.5.L842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitt BR, Weng W, Steve AR, Blakely RD, Reynolds I, Davies P. Serotonin increases DNA synthesis in rat proximal and distal pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells in culture. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:L178–86. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.2.L178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doi S, Damron DS, Horibe M, Murray PA. Capacitative Ca2+ entry and tyrosine kinase activation in canine pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L118–30. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.1.L118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mauban JR, Wilkinson K, Schach C, Yuan JX. Histamine-mediated increases in cytosolic [Ca2+] involve different mechanisms in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle and endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C325–36. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00236.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohlstein EH, Douglas SA, Sung CP, Yue TL, Louden C, Arleth A, et al. Carvedilol, a cardiovascular drug, prevents vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, migration, and neointimal formation following vascular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6189–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu Y, Sweeney M, Zhang S, Platoshyn O, Landsberg J, Rothman A, et al. PDGF stimulates pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by upregulating TRPC6 expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C316–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00125.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang XR, Lin MJ, Sham JS. Physiological functions of transient receptor potential channels in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;661:109–22. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-500-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Deng X, Hewavitharana T, Soboloff J, Gill DL. Stim, ORAI and TRPC channels in the control of calcium entry signals in smooth muscle. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:1127–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.05018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albert AP, Saleh SN, Peppiatt-Wildman CM, Large WA. Multiple activation mechanisms of store-operated TRPC channels in smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2007;583:25–36. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.137802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sweeney M, Yu Y, Platoshyn O, Zhang S, McDaniel SS, Yuan JX. Inhibition of endogenous TRP1 decreases capacitative Ca2+ entry and attenuates pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L144–55. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00412.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golovina VA, Platoshyn O, Bailey CL, Wang J, Limsuwan A, Sweeney M, et al. Upregulated TRP and enhanced capacitative Ca2+ entry in human pulmonary artery myocytes during proliferation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H746–55. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Large WA, Wang Q. Characteristics and physiological role of the Ca2+-activated Cl- conductance in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C435–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leblanc N, Ledoux J, Saleh S, Sanguinetti A, Angermann J, O’Driscoll K, et al. Regulation of calcium-activated chloride channels in smooth muscle cells: a complex picture is emerging. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;83:541–56. doi: 10.1139/y05-040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chipperfield AR, Harper AA. Chloride in smooth muscle. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2000;74:175–221. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(00)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E, et al. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science. 2008;322:590–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1163518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell. 2008;134:1019–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS, et al. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature. 2008;455:1210–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cornfield DN, Stevens T, McMurtry IF, Abman SH, Rodman DM. Acute hypoxia increases cytosolic calcium in fetal pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:L53–6. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.265.1.L53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonnet S, Belus A, Hyvelin JM, Roux E, Marthan R, Savineau JP. Effect of chronic hypoxia on agonist-induced tone and calcium signaling in rat pulmonary artery. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L193–201. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.1.L193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gögelein H, Dahlem D, Englert HC, Lang HJ. Flufenamic acid, mefenamic acid and niflumic acid inhibit single nonselective cation channels in the rat exocrine pancreas. FEBS Lett. 1990;268:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80977-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ottolia M, Toro L. Potentiation of large conductance KCa channels by niflumic, flufenamic, and mefenamic acids. Biophys J. 1994;67:2272–9. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80712-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster RR, Zadeh MA, Welsh GI, Satchell SC, Ye Y, Mathieson PW, et al. Flufenamic acid is a tool for investigating TRPC6-mediated calcium signalling in human conditionally immortalised podocytes and HEK293 cells. Cell Calcium. 2009;45:384–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuchs B, Dietrich A, Gudermann T, Kalwa H, Grimminger F, Weissmann N. The role of classical transient receptor potential channels in the regulation of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;661:187–200. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-500-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu W, Wang J, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT. Differences in STIM1 and TRPC expression in proximal and distal pulmonary arterial smooth muscle are associated with differences in Ca2+ responses to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L104–13. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00058.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song MY, Makino A, Yuan JX. STIM2 contributes to enhanced store-operated Ca2+ entry in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2011;1:84–94. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.78106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng LC, McCormack MD, Airey JA, Singer CA, Keller PS, Shen XM, et al. TRPC1 and STIM1 mediate capacitative Ca2+ entry in mouse pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2009;587:2429–42. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.172254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung S, Strotmann R, Schultz G, Plant TD. TRPC6 is a candidate channel involved in receptor-stimulated cation currents in A7r5 smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C347–59. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00283.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tai K, Hamaide MC, Debaix H, Gailly P, Wibo M, Morel N. Agonist-evoked calcium entry in vascular smooth muscle cells requires IP 3 receptor-mediated activation of TRPC1. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:135–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maruyama Y, Nakanishi Y, Walsh EJ, Wilson DP, Welsh DG, Cole WC. Heteromultimeric TRPC6-TRPC7 channels contribute to arginine vasopressin-induced cation current of A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2006;98:1520–7. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000226495.34949.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng G, Lu W, Li X, Chen Y, Zhong N, Ran P, et al. Expression of store-operated Ca2+ entry and transient receptor potential canonical and vanilloid-related proteins in rat distal pulmonary venous smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L621–30. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00176.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu SZ, Beech DJ. TrpC1 is a membrane-spanning subunit of store-operated Ca2+ channels in native vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2001;88:84–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brueggemann LI, Markun DR, Henderson KK, Cribbs LL, Byron KL. Pharmacological and electrophysiological characterization of store-operated currents and capacitative Ca2+ entry in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:488–99. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.095067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDaniel SS, Platoshyn O, Wang J, Yu Y, Sweeney M, Krick S, et al. Capacitative Ca2+ entry in agonist-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L870–80. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.5.L870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin MJ, Leung GP, Zhang WM, Yang XR, Yip KP, Tse CM, et al. Chronic hypoxia-induced upregulation of store-operated and receptor-operated Ca2+ channels in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells: A novel mechanism of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2004;95:496–505. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000138952.16382.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ng LC, Gurney AM. Store-operated channels mediate Ca2+ influx and contraction in rat pulmonary artery. Circ Res. 2001;89:923–9. doi: 10.1161/hh2201.100315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hassoun PM, Mouthon L, Barberá JA, Eddahibi S, Flores SC, Grimminger F, et al. Inflammation, growth factors, and pulmonary vascular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:S10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenwood IA, Ledoux J, Leblanc N. Differential regulation of Ca2+ -activated Cl- currents in rabbit arterial and portal vein smooth muscle cells by Ca2+ -calmodulin-dependent kinase. J Physiol. 2001;534:395–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan XJ. Role of calcium-activated chloride current in regulating pulmonary vasomotor tone. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L959–68. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.5.L959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manoury B, Tamuleviciute A, Tammaro P. TMEM16A/anoctamin 1 protein mediates calcium-activated chloride currents in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2010;588:2305–14. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.189506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartzell HC, Yu K, Xiao Q, Chien LT, Qu Z. Anoctamin/TMEM16 family members are Ca2+ - activated Cl- channels. J Physiol. 2009;587:2127–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hwang SJ, Blair PJ, Britton FC, O’Driscoll KE, Hennig G, Bayguinov YR, et al. Expression of anoctamin 1/TMEM16A by interstitial cells of Cajal is fundamental for slow wave activity in gastrointestinal muscles. J Physiol. 2009;587:4887–904. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang F, Rock JR, Harfe BD, Cheng T, Huang X, Jan YN, et al. Studies on expression and function of the TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21413–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911935106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu MH, Kim TW, Ro S, Yan W, Ward SM, Koh SD, et al. A Ca2+ -activated Cl- conductance in interstitial cells of Cajal linked to slow wave currents and pacemaker activity. J Physiol. 2009;587:4905–18. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rock JR, O’Neal WK, Gabriel SE, Randell SH, Harfe BD, Boucher RC, et al. Transmembrane protein 16A (TMEM16A) is a Ca2+ -regulated Cl- secretory channel in mouse airways. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14875–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ousingsawat J, Martins JR, Schreiber R, Rock JR, Harfe BD, Kunzelmann K. Loss of TMEM16A causes a defect in epithelial Ca2+ -dependent chloride transport. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28698–703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.012120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davis AJ, Forrest AS, Jepps TA, Valencik ML, Wiwchar M, Singer CA, et al. Expression profile and protein translation of TMEM16A in murine smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C948–59. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00018.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Gibbons SJ, Bardsley MR, Lorincz A, Pozo MJ, Pasricha PJ, et al. Ano1 is a selective marker of interstitial cells of Cajal in the human and mouse gastrointestinal tract. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1370–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00074.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferrera L, Caputo A, Ubby I, Bussani E, Zegarra-Moran O, Ravazzolo R, et al. Regulation of TMEM16A chloride channel properties by alternative splicing. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33360–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.046607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stöhr H, Heisig JB, Benz PM, Schöberl S, Milenkovic VM, Strauss O, et al. TMEM16B, a novel protein with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity, associates with a presynaptic protein complex in photoreceptor terminals. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6809–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5546-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pifferi S, Dibattista M, Menini A. TMEM16B induces chloride currents activated by calcium in mammalian cells. Pflügers Arch. 2009;458:1023–38. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0684-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stephan AB, Shum EY, Hirsh S, Cygnar KD, Reisert J, Zhao H. ANO2 is the cilial calcium-activated chloride channel that may mediate olfactory amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11776–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903304106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Forrest AS, Angermann JE, Raghunathan R, Lachendro C, Greenwood IA, Leblanc N. Intricate interaction between store-operated calcium entry and calcium-activated chloride channels in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;661:31–55. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-500-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liang W, Ray JB, He JZ, Backx PH, Ward ME. Regulation of proliferation and membrane potential by chloride currents in rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 2009;54:286–93. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]