Abstract

This study focused on the identification of conceptually meaningful groups of individuals based on their joint self-concept differentiation (SCD) and self-concept clarity (SCC) scores. Notably, we examined whether membership in different SCD-SCC groups differed by age and also was associated with differences in psychological well-being (PWB). Cluster analysis revealed five distinct SCD-SCC groups: a self-assured, unencumbered, fragmented-only, confused-only, and fragmented and confused group. Individuals in the self-assured group had the highest mean scores for positive PWB and the lowest mean scores for negative PWB, whereas individuals in the fragmented and confused group showed the inverse pattern. Findings showed that it was psychologically advantageous to belong to the self-assured group at all ages. As hypothesized, older adults were more likely than young adults to be in the self-assured cluster, whereas young adults were more likely to be in the fragmented and confused cluster. Thus, consistent with extant theorizing, age was positively associated with psychologically adaptive self-concept profiles.

This study examined whether conceptually meaningful subgroups of individuals can be identified based on their joint scores on self-concept differentiation (SCD) and self-concept clarity (SCC). Specifically, we considered whether individuals within such subgroups differed systematically from one another on measures of positive and negative psychological well-being (PWB). Of interest to us was also whether there were age differences in the distribution of adults across the SCD-SCC groups and whether age moderated the association between PWB and SCD-SCC grouping.

SELF-CONCEPT DIFFERENTIATION, SELF-CONCEPT CLARITY, AND PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING

Research has increasingly focused on aspects of adults’ self-representations1 that are believed to have adaptive value (Campbell, Assanand, & DiPaula, 2003; Linville, 1987; Showers, Abramson, & Hogan, 1998). Two such aspects are self-concept differentiation (SCD) and self-concept clarity (SCC). SCD is a structural aspect of the self-concept (Diehl, Hastings, & Stanton, 2001; Donahue, Robins, Roberts, & John, 1993) and is operationally defined as the extent to which a person’s self-representations vary across social roles or situations (e.g., self as family member, self as worker, self with friends).

From a theoretical point of view, SCD has been of interest to social, clinical, and developmental psychologists because it has been debated whether and to what extent SCD may be indicative of social specialization or indicative of a fragmented self-concept. Some theorists view a high level of SCD as an indication of specialized identities that facilitate coping with the diverse social role demands of modern life (Campbell et al., 2003; Gergen, 1991) or the demands of different life stages (Harter & Monsour, 1991). In contrast, other theorists, including Erikson (1968), James (1890/1963), and Rogers (1959) have emphasized that the psychologically healthy individual is characterized by a coherent self-concept that gives him or her a sense of identity, continuity, and biographical meaningfulness over time (cf. Brandtstädter & Greve, 1994). Although these latter theorists acknowledge that individuals’ self-representations need to be responsive to situational demands, they also emphasize that a coherent and integrated self-concept is a sign of psychological adjustment and mental health (Block, 1961; Rogers, 1959).

Past research has shown that greater SCD tends to be associated with poorer emotional adjustment and lower PWB (Bigler, Neimeyer, & Brown, 2001; Diehl et al., 2001; Donahue et al., 1993). For example, Donahue et al. (1993) found that SCD was positively associated with anxiety, depressive symptoms, and neuroticism, and negatively associated with self-esteem and measures of life satisfaction. Similar findings supporting the negative relationship between SCD and measures of PWB have been reported by Bigler et al. (2001) and Diehl et al. (2001), leading to the overall conclusion that measures of SCD seem to assess self-concept fragmentation rather than self-concept specialization.

In light of this evidence, Bigler et al. (2001) suggested that a more stringent examination of the extent to which SCD is reflective of specialization versus fragmentation, may require incorporating another structural aspect of individuals’ self-concept, namely the clarity with which individuals describe their self-concept. Specifically, Bigler et al. (2001) proposed that the effects of SCD may be qualified by an individual’s level of self-concept clarity (SCC; Campbell et al., 1996).

Self-concept clarity (SCC) is defined as the extent to which the contents of a person’s self-concept “are clearly and confidently defined, internally consistent, and temporally stable” (Campbell et al., 1996, p. 141). Thus, SCC is conceived as a relatively stable person characteristic that can be reliably captured in self-reports. Campbell et al. (1996) developed a self-report questionnaire to assess SCC and examined the nomological network of the construct, showing that SCC correlated positively with self-esteem, positive affect, and extraversion, and negatively with private self-consciousness, negative affect, and neuroticism. In a series of subsequent studies with young adults only, Campbell and colleagues (2003) found that SCC, conceived as a marker of self-concept unity, had a moderate positive association with self-esteem and a moderate negative correlation with neuroticism.

Overall, these studies revealed that SCD and SCC show inverse relations with measures of self-esteem, positive and negative affect, and with personality traits, such as neuroticism or extraversion. Such patterns suggest that SCD and SCC themselves should be inversely related. Indeed, such a moderate inverse relationship was found by Campbell and colleagues (2003). SCD and SCC, however, are not simply opposite ends of the same continuum. Rather, research suggests that they share only a modest amount of variance (Bigler et al., 2001; Campbell et al., 2003) and that each accounts for unique amounts of variance in outcomes indicative of psychological adjustment (Bigler et al., 2001).

In one of the few joint considerations of SCD and SCC, Bigler et al. (2001) argued that SCD and SCC appear to represent different aspects of the self-structure, but that it may be relatively difficult for adults to maintain high levels of SCC in the face of a moderate to high level of SCD. Thus, although it is theoretically possible that adults could have a strong sense of clarity within the context of possessing multiple and differing role-specific selves, it remains unclear whether adults with such joint SCD-SCC self-structures exist in practice. Indeed, Bigler et al.’s (2001) findings suggested that although SCD and SCC did not interact in a linear fashion to influence psychological outcomes they may, nonetheless, combine in non-linear ways and produce qualitatively distinct SCD-SCC subgroups.

The identification of qualitatively distinct subgroups is important for several reasons. First, the correlates of SCD and SCC have usually been assessed separately (Campbell et al., 1996; Donahue et al., 1993). However, if these two variables interact to form qualitatively different groups of individuals, this would support the notion that research on the structural aspects of adults’ self-representations could benefit from adopting a multivariate perspective. Second, if adults’ SCD and SCC scores combine to form subgroups in non-linear ways, then it is currently unclear what profiles of PWB and what specific vulnerabilities individuals in these subgroups might show. For example, certain forms of adjustment disorders, disorders of the self, or personality disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) might be related to specific SCD-SCC combinations and identification of specific risk profiles may potentially be of relevance to practitioners who provide counseling or assessment services. Finally, there is a considerable body of research that has examined the role of age and developmental change in self-concept organization across different stages of the lifespan (cf. Diehl, Youngblade, Hay, & Chui, 2011; Harter, 1998). However, relatively little work has been done that has applied a developmental perspective to the examination of the structural aspects of individuals’ self-concept, such as SCD and SCC. Thus, an understanding of how SCD and SCC combine and interact may also help to shed light on the effect of different self-concept organizations on PWB and whether this effect differs for different age groups.

SCD, SCC, AND THE SELF-CONCEPT IN ADULTHOOD

Research on the development of self-representations is an integral part of the study of social-emotional development across the lifespan (Diehl et al., 2011; Harter, 2006; Labouvie-Vief, Chiodo, Goguen, Diehl, & Orwoll, 1995). This research covers the development of self-awareness from infancy through late adulthood (cf. Diehl et al., 2011). Indeed, research has shown that self-representations develop in a fairly predictable developmental sequence early in life (Damon & Hart, 1988; Harter, 1999). This developmental sequence includes an increasing differentiation into role-specific multiple selves by the end of adolescence or beginning of early adulthood (Damon & Hart, 1988; Harter, 1998; Montemayor & Eisen, 1977; Rosenberg, 1986). Thus, by early adulthood individuals are confronted with the developmental task of coordinating multiple, role- or context-specific self-representations into a coherent identity—a task that builds on progressions in cognitive and social-emotional development (Harter & Monsour, 1992). Researchers have argued that the formation of a coherent identity is a cornerstone for successful social and emotional development in midlife and late adulthood (Erikson, 1963; Marcia, 1980; Waterman & Archer, 1990). How the structural features of adults’ self-representations, such as SCD and SCC, operate across the adult lifespan is, however, not well understood. Thus, theoretical reasoning on self-concept development in adulthood often results in the general proposition that individuals’ self-representations become more internally consistent and integrated (i.e., SCD decreases) and clear (i.e., SCC increases) with age.

Currently, there are only a few studies that have examined age differences or age-related changes in SCD or SCC. Studies that have examined the association between SCD and age across the adult lifespan have provided a somewhat mixed picture. On one hand, Diehl et al. (2001) found a curvilinear association between SCD and age, showing that both young and very old adults had similar levels of SCD, whereas middle-aged and young–old adults had the lowest levels of SCD. On the other hand, Diehl and Hay (2010) found in another study that SCD had a negative linear association with age, suggesting that SCD tends to decrease with age. Although these discrepant findings cannot be completely reconciled, the findings of the second study are consistent with findings reported by Donahue et al. (1993). More importantly, however, there is some evidence suggesting that age moderates the effect of SCD on measures of PWB. Specifically, Diehl et al. (2001) showed that the association between SCD and PWB was significantly stronger in older adults than in younger adults. That is, greater SCD in older adults was associated with significantly lower positive PWB and significantly higher negative PWB than in younger adults. Developmentally, therefore, it appears that having a differentiated self-concept is more maladaptive in old age than in younger adulthood. This finding might also reflect that self-concept coherence (i.e., low SCD) becomes particularly important in late life when adults experience losses or are challenged by physical or psychological declines (Diehl et al., 2001). Alternatively, this pattern suggests that in young adulthood elevated SCD scores may be part of normative identity formation (Arnett, 2000).

Comparatively little research has examined the developmental trajectory of SCC across adulthood. Recently, Lodi-Smith and Roberts (2010) examined age differences in SCC scores in adults aged 18 to 94 and found that SCC had a curvilinear relationship with age. Specifically, SCC was positively related to age from young adulthood through middle age and negatively related to age in later adulthood. Furthermore, Lodi-Smith and Roberts found that the association between age and SCC was moderated by income and health-related limitations. Specifically, they found that controlling for income resulted in young adults having similar SCC scores as middle-aged adults. Additionally, older adults with few health-related limitations did not exhibit decreased SCC compared to middle-aged adults.

Lodi-Smith and Roberts’ (2010) findings are in keeping with theorizing that particular social roles (i.e., work) and living conditions (i.e., health) play a role in the development of, and change in, self-concept. Notably, when coupled with research suggesting linear age differences in SCD (Donahue et al., 1993; Diehl & Hay, 2010), Lodi-Smith and Roberts’ (2010) findings also raise the possibility that SCD and SCC may not exhibit parallel trajectories of change with age. Rather, adults’ self-concept may tend to decrease in terms of differentiation (i.e., SCD) across adulthood, but peak in clarity (i.e., SCC) in midlife after which clarity may plateau or decline. Such differential patterns of change underscore the possibility that SCD and SCC may combine in non-linear ways and that the distribution of distinct SCD-SCC combinations may vary across adulthood.

Finally, although information on the role of age in the associations between SCD, SCC, and PWB is limited, theory (Erikson, 1963; Marcia, 1980; Waterman & Archer, 1990) and empirical evidence (Diehl et al., 2001) suggest that possessing SCD and SCC scores that are on the maladaptive ends of those spectrums might render older adults most vulnerable to experiencing lower PWB compared to younger adults. Thus, it seems reasonable to ask whether SCD-SCC subgroups may be differently distributed across the major age periods of the adult lifespan and whether age moderates the association between SCD-SCC group membership and PWB.

ASSESSING THE JOINT OPERATION OF SCD AND SCC: A TAXOMETRIC APPROACH

Past studies have shown moderate inverse correlations between SCD and SCC (Bigler et al., 2001). On the one hand, these correlations suggest that the associations of SCD and SCC with measures of PWB should not be completely independent from each other. On the other hand, the studies by Bigler et al. (2001) did not support the hypothesis that the association of SCD with measures of emotional adjustment and well-being would be moderated by SCC. Rather, as we have argued, SCD and SCC may not interact in a linear fashion but may jointly combine to form distinct groups of individuals that are qualitatively different and, by implication, may show different profiles of psychological adjustment.2

Groups of individuals that are presumed to be qualitatively different from each other are often formed based on the high vs. low dichotomization of quantitative variables (i.e., median split method). Although this approach is widely used in the social sciences, it is a practice that should be avoided for a number of statistical and substantive reasons (MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, 2002). If qualitatively different groups of individuals exist regarding the interaction of SCD and SCC, then taxometric methods should be used to identify and name these groups (Waller & Meehl, 1998). Taxometric methods permit the identification of classes of individuals who differ in kind as well as degree (Meehl, 1992) and include techniques such as cluster analysis, mixture models, or latent class analysis. The present study used cluster analysis (Hair & Black, 2000) to examine whether distinct groups could be identified based on individuals’ joint SCD and SCC scores.

Theoretical reasoning and findings from earlier work (Bigler et al., 2001; Donahue et al., 1993), suggest at a minimum three a priori clusters of SCD-SCC combinations. One cluster may consist of individuals who can be characterized as having a coherent and clearly defined self-concept. Individuals in this group could be labeled as self-assured, because they tend to report similar self-representations across social roles and situations (i.e., low SCD) and little confusion about their self-concept (i.e., high SCC). A conceptually contrasting cluster may consist of individuals who can be characterized as having a fragmented (i.e., high SCD) and confused self-concept (i.e., low SCC). Conceptually it also seems plausible that these two clusters are complemented by a third cluster in which individuals are characterized by average SCD and average SCC. Individuals in this group could be labeled as being unencumbered about their self-concept, because they tend to describe themselves as fairly consistent across roles and situations and report a fair amount of clarity about their self-representations.

Aside from these three main clusters, theory suggests that an additional cluster could emerge. Specifically, this cluster may consist of individuals who see themselves very different across social roles and situations (i.e., high SCD) but are completely aware that their different behaviors are in response to the demands of different roles and situations (i.e., high SCC). The self-representations and behaviors of individuals in such a cluster would be consistent with what Gergen (1991) described as socially specialized individuals.

Indeed, and as noted above, research on age differences in SCD (Donahue et al., 1993; Hay & Diehl, 2010) and SCC (Lodi-Smith & Roberts, 2010) suggests that the developmental trajectories of SCD and SCC may diverge, particularly in later adulthood. Consequently, there may be age differences in the distribution of the SCD-SCC clusters across adulthood. Notably, older adults may be more likely than younger or middle-aged adults to report similar self-representations across social roles and situations (i.e., low SCD) but experience some confusion about their self-concept (i.e., high SCC). Exploring whether such clusters of adults exist can be addressed using taxometric methods such as cluster analysis.

THE CURRENT STUDY

Given this theoretical and empirical background, the current study examined evidence for qualitatively different subgroups of individuals based on their joint SCD and SCC scores. Specifically, we addressed this question in a sample covering the entire adult lifespan. In addition, we examined mean level differences among the identified subgroups with regard to multiple measures of positive and negative PWB. Multiple measures were chosen for two reasons. First, previous studies mostly relied on single indicators of either positive or negative PWB, thus assessing these domains of human functioning in a fairly narrow way (Keyes, 2002; Ryff, 1995). Second, inclusion of indicators of both positive and negative PWB permitted us to address the question whether the markers of positive PWB would show the inverse pattern of mean level differences across the different SCD-SCC subgroups than the markers of negative PWB. Evidence of such an inverse pattern would strengthen the argument that the effect of the different SCD-SCC subgroups is not limited to certain kinds of measures but generalizes across a large number of measures of positive and negative PWB. Finally, a diverse sample of adults was used because much self-concept research has relied on homogeneous samples of college students, leaving the generalizability of the findings to other age groups an open question.

Current research suggests that systematic mean level differences are likely to exist among the SCD-SCC subgroups with regard to measures of positive and negative PWB. In terms of measures of positive PWB, we expected that the highest mean levels would be found in the self-assured and the socially specialized groups. Conversely, we expected the lowest mean levels in the fragmented and confused groups. We expected that the scores of the unencumbered group would fall in between. In terms of markers of negative PWB, we expected the inverse pattern of mean level differences. Finally, in keeping with developmental theory and research on the self-concept (Diehl et al., 2001; Donahue et al., 1993; Harter & Monsour, 1992), we expected that the different SCD-SCC subgroups would be differently distributed across adulthood. Specifically, we expected that a larger number of older adults would belong to the self-assured group compared to young adults. Conversely, we expected that younger adults would be more likely to be in the confused and fragmented groups compared to older adults. Finally, we expected that certain SCD-SCC organizations would be, more or less, adaptive at different stages of adulthood. That is, we expected that age would moderate the association between SCD-SCC groups and measures of PWB. Notably, we expected that in later adulthood it would be particularly maladaptive to have a fragmented and confused self-concept, whereas this may be developmentally normative in earlier adulthood.

METHOD

Participants

The study sample consisted of 279 adults who were part of a larger study on coping with daily stress (see Diehl & Hay, 2010). After an analysis of statistical outliers related to the cluster analysis (see explanation below) data from 9 participants were excluded, leaving a final sample of 270 adults (129 women, 141 men). Participants were recruited using a mix of sampling procedures. Specifically, 27% of participants were recruited through random digit dialing, 22% through letters of invitation to University of Florida alumni, 45% through convenience methods (e.g., word-of-mouth, flyers, newspaper ads) and 5% through a retirement community. Participants ranged in age from 20 to 88 years (M = 46.0 years, SD = 22.2 years) and were recruited from a tri-county area in North Central Florida. The sample included young adults (n = 103; age range 20–39 years), middle-aged adults (n = 89; age range 40–59 years), and older adults (n = 78; age 60 and older). In each age group, men and women were about equally distributed. About 85% of the participants were Caucasian. Participants reported they were in good health (M = 5.16, SD = 0.86; 1 = very poor, 6 = very good), and satisfied with their lives (M = 4.64, SD = 0.70; 1 = extremely unhappy, 6 = extremely happy). Approximately half of the young adults were employed (full- or part-time) and half were students. The majority of the middle-aged adults were employed (87%), whereas the majority of the older adults (70%) were retired.

Procedure

A phone screening interview was used to establish potential participants’ eligibility for enrollment in the study (i.e., no major sensory impairments, no concurrent depression, no history of severe mental illness, being physically able to come to the testing location, and no cognitive impairment). Individuals who agreed to participate were tested at the Adult Development and Aging laboratory at the University of Florida. Data collection consisted of a 2-hour baseline session as well as daily diary and interview sessions during the diary portion of the study. Testing sessions were conducted individually and lasted about 2 hours. Testing was conducted by trained research assistants and all measures were administered in the same order to each participant. Participants received a reimbursement of $20.00 for their participation in the baseline session. The present study used data from the baseline session. The full study protocol and procedures are available upon request.

Measures

Self-Concept Differentiation

Level of SCD was assessed using the method developed by Block (1961). For each of five role-specific self-representations (i.e., self with family, self with significant other, self with a close friend, self with a coworker, and true self), participants rated 40 attributes in terms of how characteristic each attribute was of them (1 = extremely uncharacteristic, 8 = extremely characteristic) with regard to that role. Participants worked on one self-representation at a time and were not permitted to refer back to their earlier ratings when they worked on subsequent self-representations. Because earlier research had shown that the order of presentation did not affect participants’ ratings (Diehl et al., 2001), attributes were presented in the same order for each self-representation. Each self-representation was presented on a separate page.

An index of SCD was derived from these attribute ratings in the following way. Separately for each study participant, the ratings for the five self-representations were intercorrelated and the resulting 5 × 5 correlation matrix was subjected to a within-person principal components analysis. The first principal component extracted represents the variance shared across a participant’s five self-representations. The remaining variance represents the unshared variance and was used as a person’s index of SCD (i.e., 100% minus the percentage of variance accounted for by the first principal component). Higher values indicate more unshared variance across the self-representations and, therefore, indicate greater SCD. It is important to note that a similar number of attributes and roles have been used in previous studies to calculate adults’ SCD index in this manner (Diehl et al., 2001; Donahue et al., 1993; Sheldon, Ryan, Rawsthorne, & Ilardi, 1997). Moreover, Diehl and Hay (2007) have shown that this procedure results in an index that was robust against several methodological criticisms. In addition, the reliability and criterion validity of this index has been established in a number of studies (Diehl et al., 2001; Donahue et al., 1993; Sheldon et al., 1997). For example, the SCD index shows significant inverse relations with self-concept related constructs that have a contrary meaning, such as self-esteem and self-acceptance, and it shows significant positive correlations with constructs such as anxiety, depression, and neuroticism (Diehl et al., 2001; Donahue et al., 1993; Sheldon et al., 1997).

Self-Concept Clarity

The Self-Concept Clarity Scale (SCCS; Campbell et al., 1996) was used to examine the clarity with which participants defined their self-concept. The SCCS consists of 12 statements (e.g., “I seldom experience conflict between the different aspects of my personality”) to which participants respond on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Consistent with Campbell et al.’s research, the internal reliability of the scale was high (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Short Psychological Well-Being Scales

The Short Psychological Well-Being (SPWB) scales (Ryff, 1989) were used to assess six dimensions of PWB. The six dimensions were derived from the literatures on lifespan development, clinical psychology and mental health (Ryff, 1989, 1995) and include Autonomy, Environmental Mastery, Personal Growth, Positive Relations with Others, Purpose in Life, and Self-Acceptance. Each dimension was measured with a 14-item scale of positively and negatively phrased items that alternated in their order across dimensions. Participants responded to each item on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). The psychometric properties of the SPWB have been examined in terms of internal consistency and test-retest reliability (6-week test-retest coefficients ranged from .81 for Personal Growth to .88 for Autonomy). Ryff and Keyes (1995) also reported findings from confirmatory factor analyses supporting the six-factor structure of the questionnaire. Coefficients of internal consistency in this study were .87, .89, .84, .88, .87, and .91 for Autonomy, Environmental Mastery, Personal Growth, Positive Relations with Others, Purpose in Life, and Self-Acceptance, respectively.

Positive and Negative Affect

The Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) was used to assess participants’ positive and negative affect. Using a scale from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely), respondents indicated how often they experienced 10 positive affective states (e.g., feeling energetic, enthusiastic) and 10 negative affective states (e.g., feeling angry, fearful) during the past week. A total score was calculated separately for positive and negative affect. The PANAS has high internal consistency and test-retest reliability and is widely used in research with adults (Watson et al., 1988). The coefficients of internal consistency were .88 and .86 for positive and negative affect, respectively.

Depressive Symptoms

The frequency of depressive symptoms was assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Participants indicated on a scale of 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time) how often, in the past week, they experienced a variety of depressive symptoms (e.g., felt sad or blue). Respondents’ answers were summed into a total score (range 0–60), with higher scores indicating greater frequency of depressive symptoms. The CES-D has been specifically recommended for use with nonclinical, community-based samples and its psychometric properties are well established (Radloff, 1977; Shaver & Brennan, 1991). The internal reliability in this study was .88.

Extraversion and Neuroticism

Participants’ levels of extraversion and neuroticism were assessed using the 12-item scales from the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992), a widely used trait measure of personality. Besides sociability, extraversion also refers to personal attributes such as being upbeat, energetic, cheerful, and optimistic. In this sense, a person’s answers to the NEO-FFI extraversion items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) reflect aspects of positive affect and some researchers have referred to extraversion as positive affectivity (Watson & Tellegen, 1985). The psychometric properties of the NEO-FFI are well established (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The internal reliability of the extraversion scale in this study was .83. The correlation between the positive affect score of the PANAS and the extraversion score was r(270) = .46, p < .001.

The items on the neuroticism scale assess a person’s tendency to experience negative affective states such as fear, sadness, embarrassment, anger, guilt, and the like. Participants responded on the same 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater emotional instability. Cronbach’s α in this study was .86. The correlation between the negative affect score of the PANAS and the neuroticism score was r(270) = .60, p < .001.

Statistical Analyses

Cluster analysis was used to identify groups of individuals with qualitatively different SCD-SCC profiles. The groups identified in the cluster analysis were then examined to determine whether they mapped onto the theoretically expected groups with regards to their SCD and SCC scores. Finally, we examined whether the identified groups differed on key sociodemographic variables and measures of positive and negative PWB.

Cluster analysis can be performed in a variety of ways (Hair & Black, 2000; Henry, Tolan, & Gorman-Smith, 2005). Before describing the specific analyses that were performed, however, it is important to note that cluster analysis is sensitive to outliers and the scaling of measures (Hair & Black, 2000). Consequently, prior to performing the cluster analysis, we conducted an outlier analysis. Based on this analysis, we excluded 7 participants because of extreme SCC scores and 2 participants because of extreme SCD scores.

Furthermore, research shows that the scale of a variable can have a large impact on the final cluster solution, particularly when the variables used in an analysis have very discrepant scales (Hair & Black, 2000). Given the large discrepancy in the scaling of the SCD and SCC variables, we used range-standardized variables in our analysis. Range standardizing places all variables on the same scale and prevents the variable with the largest metric from dominating the results (Henry et al., 2005; Milligan & Cooper, 1988). Unlike other methods of standardization (e.g., creating z-scores), using range standardization also has the advantage of keeping the original variances intact (Milligan & Cooper, 1988).

After a thorough review of cluster analytic techniques, a hierarchical agglomerative cluster analysis using squared Euclidean distance association coefficients and Ward’s cluster method was performed (Henry et al., 2005; Mandara & Murray, 2000). This method first estimates the similarity among all individuals using the squared Euclidean distance, one of the most commonly used distance coefficients (Hair & Black, 2000). Then, in the hierarchical agglomerative method, clusters are formed by successively combining people or groups of people who are most similar. With the Ward’s method, the distance between people or groups of people is the sum of squares between two clusters summed over all variables. Ward’s method tends to produce clusters with a small number of observations and relatively low variance within each group.

One important decision in cluster analysis is related to determining the number of clusters to retain. Various strategies exist for determining the number of acceptable clusters, with each one having its advantages and disadvantages (Haselager, Cillesen, Van Lieshout, Risken-Walraven, & Hartup, 2002; Henry et al., 2005; Litwin, 2001). Based on a review of the literature on this topic, we examined each solution to determine when combining clusters resulted in large increases in the similarity measure. Because we used a distance measure of similarity, large increases in the similarity index indicate that the combined clusters are not highly similar (Hair & Black, 2000). We also considered how fragmented the cluster solution was. When clusters contained fewer than 10 individuals, we did not consider it a valid and substantively meaningful solution (Haselager et al., 2002).

RESULTS

Descriptive Findings

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and ranges of the measures included in the study. These descriptive statistics were similar to the ones reported by other studies (e.g., Campbell et al., 1996; Donahue et al., 1993; Ryff, 1989; Watson et al., 1988).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-concept differentiation | .16 | .10 | .00–.44 |

| Self-concept clarity | 43.49 | 8.25 | 22–60 |

| Autonomy | 66.36 | 9.54 | 41–84 |

| Environmental mastery | 63.70 | 10.83 | 31–84 |

| Personal growth | 70.79 | 7.87 | 43–84 |

| Positive relations with others | 67.39 | 11.18 | 33–84 |

| Purpose in life | 68.74 | 9.92 | 30–84 |

| Self-acceptance | 66.39 | 12.29 | 26–84 |

| Positive affect | 34.79 | 5.82 | 12–49 |

| Negative affect | 17.90 | 5.89 | 10–43 |

| Depressive symptoms | 8.70 | 6.87 | 0–40 |

| Extraversion | 30.63 | 7.39 | 9–47 |

| Neuroticism | 15.14 | 8.19 | 0–42 |

SCD-SCC Clusters

On the basis of the criteria outlined above, a five-cluster solution was the most appropriate solution obtained by the cluster analysis. The means and standard deviations for SCD and SCC for each cluster are shown in Table 2. The first cluster included 80 individuals with low SCD and high SCC scores indicating that individuals in this cluster had a coherent and clearly defined self-concept. Thus, this cluster represented the hypothesized self-assured group. The second cluster included 23 individuals with high SCD and low SCC scores and represented the fragmented and confused group.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Self-Concept Differentiation and Self-Concept Clarity by Cluster

| Cluster | Self-concept differentiation

|

Self-concept clarity

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Self-assured (n = 80) | .08 | .04 | 51.74 | 4.45 |

| Unencumbered (n = 82) | .13 | .04 | 44.18 | 2.78 |

| Confused only (n = 44) | .17 | .04 | 34.41 | 3.72 |

| Fragmented only (n = 41) | .30 | .06 | 43.90 | 5.64 |

| Fragmented and confused (n = 23) | .30 | .05 | 29.00 | 3.68 |

The third cluster included 44 individuals with relatively low SCC and average SCD scores. This cluster contained adults who were primarily confused about their self-concept; hence, we labeled this cluster “confused-only.” A fourth cluster included 41 individuals with high SCD and average SCC scores. Individuals in this cluster were primarily characterized by fragmented self-representations and, hence, this cluster was labeled “fragmented-only.” The final cluster included 82 individuals who were characterized by average SCD and average SCC scores. Thus, this cluster represented the third hypothesized group that we referred to as “unencumbered.” The cluster analysis did not identify a SCD-SCC combination that would have been indicative of a socially specialized self-concept (i.e., both high SCD and high SCC).

SCD-SCC Cluster Differences in Age Group, Gender, and Psychological Well-Being

We examined whether cluster assignment differed by age group or gender. There were no significant differences in cluster assignment by gender, χ2(4) = 3.78, p > .05. Significant differences in cluster assignment, however, were found by age group, χ2(8) = 32.88, p < .001. Follow-up analyses showed significant age group differences in terms of assignment to the confused-only, the fragmented-only, and the self-assured groups. Specifically, older adults were more likely than young adults, χ2(1) = 10.82, p < .001, to be assigned to the self-assured group. Conversely, compared to older adults, a significantly greater number of young adults were assigned to the confused-only cluster, χ2(1) = 8.25, p < .001, and the fragmented-only cluster, χ2(1) = 8.51, p < .001. In addition, a greater number of young adults was assigned to the fragmented-only cluster, χ2(1) = 6.57, p < .05, compared to middle-aged adults.

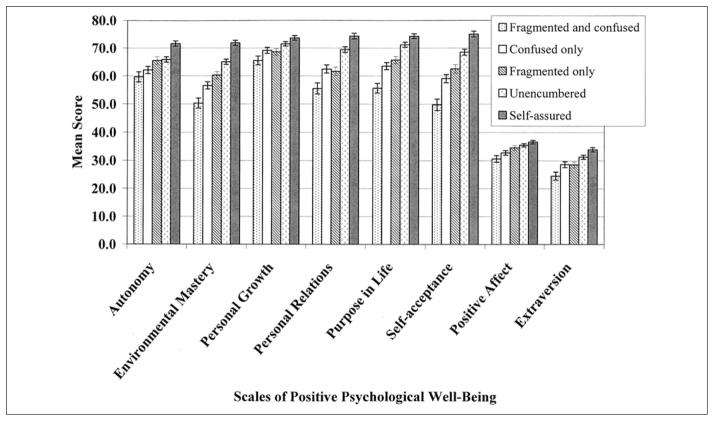

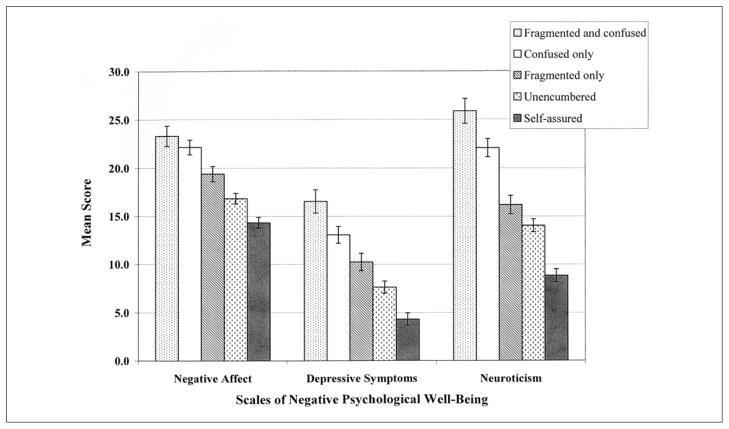

Next we examined age group and cluster differences in positive and negative PWB using two multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs). The dependent variables in the first MANOVA were the measures of positive PWB, whereas the markers of negative PWB were the dependent variables in the second MANOVA. The Age Group × Cluster interactions were not statistically significant for both the positive and negative indicators of PWB, indicating that the associations between psychological well-being and cluster membership were not moderated by age group but were the same across age groups. Both MANOVAs, however, yielded a significant multivariate effect of cluster membership, Wilks’ Λ = .46, F(32, 953) = 7.01, p < .001, η2 = .18 and Wilks’ Λ = .51, F(12, 696) = 16.99, p < .001, η2 = .20, respectively. The significant multivariate effect of cluster membership in each analysis was due to significant (p < .001) univariate effects for all variables included in the analyses. Table 3 shows the means and standard deviations for the measures of positive PWB by cluster and Table 4 displays the means and standard deviations for the measures of negative PWB. Figures 1 and 2 provide a pictorial representation of the mean differences across clusters.3

Table 3.

Results of the Multivariate Analysis of Variance Examining Cluster Differences for Measures of Positive Psychological Well-Being

| Variable | Fragmented and confused n = 23 |

Confused only n = 44 |

Fragmented only n = 41 |

Unencumbered n = 82 |

Self-assured n = 80 |

F(4, 265) | Partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | 59.61a (8.38) | 62.09a (9.73) | 65.51a (10.10) | 65.83b (8.51) | 71.61c (7.79) | 13.38*** | .17 |

| Environmental mastery | 50.30a (9.87) | 56.57b,c (9.47) | 60.26c (8.74) | 65.02d (8.80) | 71.87c (7.00) | 42.53*** | .39 |

| Personal growth | 65.50a,b (9.92) | 69.16a,b (7.25) | 68.59a,b (8.27) | 71.49a,b,c (6.85) | 73.61c (7.17) | 7.22*** | .10 |

| Positive relations with others | 55.53a (9.85) | 62.45a (10.42) | 61.63a (10.46) | 69.47b (9.36) | 74.34c (8.31) | 27.60*** | .29 |

| Purpose in life | 55.67a (10.41) | 63.57b (9.23) | 65.71b (9.10) | 71.24c (8.42) | 74.32c (6.04) | 31.28*** | .32 |

| Self-acceptance | 49.77a (10.98) | 59.05b (10.84) | 62.49b,c (12.04) | 68.51c (9.43) | 75.04d (7.29) | 41.75*** | .39 |

| Positive affect | 30.61a (7.31) | 32.73a,b (5.38) | 34.51a,b,c (7.33) | 35.46c (4.82) | 36.58c (4.73) | 7.14*** | .10 |

| Extraversion | 24.48a (8.62) | 28.60a (8.16) | 28.54a (7.21) | 31.28b (5.87) | 33.91b,c (6.37) | 11.21*** | .15 |

Note: Standard deviations are shown in parentheses. Means with different subscripts differ significantly at p < .05 by the Games-Howell procedure.

p < .001.

Table 4.

Results of the Multivariate Analysis of Variance Examining Cluster Differences for Measures of Negative Psychological Well-Being

| Variable | Fragmented and confused n = 23 |

Confused only n = 44 |

Fragmented only n = 41 |

Unencumbered n = 82 |

Self-assured n = 80 |

F(4, 265) | Partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative affect | 23.30a (6.40) | 22.14a,b (6.53) | 19.39a,b,c (5.31) | 16.84c (4.52) | 14.33d (3.83) | 26.45*** | .29 |

| Depressive symptoms | 15.54a,b (9.87) | 13.07a,b,c (9.47) | 10.24b,c,d (8.74) | 7.65d (8.80) | 4.33c (7.00) | 30.15*** | .31 |

| Neuroticism | 25.87a (9.92) | 22.09a,b (7.25) | 16.20c,d (8.27) | 14.04d (6.85) | 8.84c (7.17) | 53.87*** | .45 |

Note: Standard deviations are shown in parentheses. Means with different subscripts differ significantly at p < .05 by the Games-Howell procedure.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Mean differences on measures of positive psychological well-being across SCD-SCC clusters.

Figure 2.

Mean differences on measures of negative psychological well-being across SCD-SCC clusters.

In terms of scales of positive PWB, Games and Howell follow-up tests (Games & Howell, 1976) showed that individuals in the self-assured cluster had significantly higher mean scores than individuals in the four other clusters on the scales of Autonomy, Environmental Mastery, Positive Relations with Others, and Self-Acceptance (see Table 3). Similarly, individuals in the unencumbered cluster had significantly higher mean scores than individuals in the fragmented and confused, confused-only, and fragmented-only clusters on the scales of Autonomy, Environmental Mastery, Positive Relations with Others, Purpose in Life, and Extra-version. Although adults in the fragmented and confused, confused-only, and fragmented-only clusters had significantly lower mean scores on the scales of positive PWB compared to adults in the self-assured group, individuals in the fragmented and the confused cluster had consistently the lowest mean scores followed by the individuals in the confused-only and the fragmented-only groups (see Figure 1).

In terms of markers of negative PWB, the pattern of mean level differences was inverse (see Figure 2). Games and Howell follow-up tests (Games & Howell, 1976) showed that individuals in the self-assured cluster had consistently the lowest mean scores on measures of negative PWB. The mean scores of individuals in the unencumbered cluster were not significantly different from the mean scores of the fragmented-only group, but significantly different from the mean scores of the fragmented and confused group and the confused-only group. Adults in the fragmented and confused group had consistently the lowest mean scores on the measures of negative PWB.

In summary, findings from the MANOVAs showed that there was a systematic pattern of mean-level differences among the identified clusters, with individuals in the self-assured cluster consistently showing the highest mean scores on measures of positive PWB and the lowest mean scores on measures of negative PWB. Conversely, adults in the fragmented and confused cluster showed consistently the lowest mean scores on measures of positive PWB and the highest mean scores on measures of negative PWB. Individuals in the confused only and fragmented only group also showed lower mean scores on measures of positive PWB and higher mean scores on measures of negative PWB, whereas adults in the unencumbered group showed mean scores closer to the self-assured cluster. Age group did not moderate the associations between cluster membership and psychological well-being.

DISCUSSION

This study examined whether qualitatively different combinations of SCD and SCC could be identified and if the SCD-SCC clusters showed systematic mean level differences for measures of positive and negative PWB and across age groups. Our findings suggested that SCD and SCC combine in ways that are associated with meaningful differences in positive and negative PWB. Furthermore, we identified meaningful age differences in the likelihood of belonging to a particular SCD-SCC cluster. Despite past evidence (Diehl et al., 2001) suggesting that particular SCD-SCC clusters would be more, or less, detrimental at particular ages, findings from the present study, however, did not support age group differences in the strength of the association between SCD-SCC clusters and PWB (i.e., no moderation effect of age group). Rather our findings suggested that at all ages the same SCD-SCC clusters were associated with maladaptive profiles of PWB, whereas other clusters were associated with adaptive profiles of PWB.

With respect to the SCD-SCC clusters, the pattern of findings supported our a priori hypotheses in terms of the major subgroups. Notably, the self-assured, unencumbered, and fragmented and confused groups were consistent with our a priori hypotheses. The data also supported two additional clusters of individuals that had (a) average self-concept coherence but low clarity (i.e., the confused-only group) or (b) low coherence (i.e., high fragmentation) but average clarity (i.e., the fragmented-only group). Although these clusters had not been hypothesized a priori, they described a sizeable number of adults and, therefore, needed to be recognized as valid clusters. At first glance, it is not clear what underlies groups of individuals that possess average scores on one aspect of self-concept and low scores on another (i.e., uncertain or fragmented). As we discuss below, however, because a greater proportion of young adults compared to older adults fell into these clusters, we speculate that adults in these clusters may be in a stage of flux or in a formative stage with respect to their self-concepts whereby they have achieved some degree of clarity or coherence, but not yet both. Understanding whether these clusters might be composed of adults whose self-concepts are in flux or formation, however, cannot be answered by the data from this study as it would require longitudinal observations. Overall, however, these findings extend earlier work by Bigler et al. (2001) by demonstrating a new approach to deriving groups of individuals that are qualitatively different based on their combined scores on SCD and SCC.

Interestingly, the data did not support a cluster of socially specialized individuals (Gergen, 1991). This finding can be interpreted in at least two different ways. First, although the conceptual reasoning in support of a group of socially specialized individuals makes intuitive sense, it might be that empirically the existence of such a group cannot be verified. Alternatively it might also be possible that the base rate of socially specialized individuals is very low and, hence, we were not able to confirm the existence of such a cluster in our sample. Indeed, as Bigler and colleagues (2001) noted, maintaining a strong sense of clarity within the context of possessing multiple and differing role-specific selves, may be psychologically too demanding in practice for most, if not all adults. At first glance, it could appear that the cluster we labeled fragmented-only represents the closest group to the hypothesized “socially specialized” group. The overall pattern of findings regarding PWB and age differences in the SCD-SCC clusters, however, speaks against such an interpretation. Notably, the socially specialized individual, as described by Gergen (1991), possesses a self-concept that is fluid, flexible, and well-suited to the demands of postmodern life. Indeed, Gergen (1991) argued such individuals would have particularly good scores on indicators of mental health. Yet our findings revealed that these adults, whom we termed fragmented-only, had PWB scores that reflected relatively poor mental health. Furthermore, the fragmented-only cluster included a disproportionate number of younger adults. If adults with high SCD and average SCC actually represented Gergen’s hypothesized “socially specialized” adults, we would likely expect greater numbers of them to be middle-aged adults, as midlife is a time of life that tends to be characterized by high role demands and responsibilities (Lachman, 2004).

Despite the lack of support for a socially specialized group of adults, in keeping with our expectations, the MANOVAs showed a consistent pattern of mean level differences on measures of positive and negative PWB across the identified subgroups. That is, individuals in the self-assured group had the highest mean scores on measures of positive PWB and the lowest mean scores on measures of negative PWB. This pattern was reversed for adults in the fragmented and confused group, and to a lesser extent for adults in the confused-only and the fragmented-only groups. In contrast, the mean scores of individuals in the unencumbered group were closer to the scores of the self-assured group. Overall, these findings were consistent with results reported by Campbell and colleagues (2003) from studies with college students showing that measures of self-concept unity were significantly related to measures of adjustment. The findings related to the fragmented and confused, the confused-only, and the fragmented-only groups were also consistent with a number of previous studies (Bigler et al., 2001; Block, 1961; Diehl et al., 2001; Diehl & Hay, 2007; Donahue et al., 1993) showing that a high level of SCD (i.e., low self-concept coherence) tends to be associated with poor emotional adjustment and poor psychological well-being. The findings from the current study suggest that this negative effect of SCD may be amplified when combined with low SCC and that a specific combination of SCD and SCC may put individuals at risk for maladjustment. For example, the average depressive symptoms score of the individuals in the fragmented and confused group was fairly close to the clinical cut-off score defined for the CES-D, suggesting that individuals in this cluster may be more likely to manifest signs of clinical depression. At the same time, we acknowledge that this group made up a relatively small proportion of the entire sample. Its relatively small size, however, likely reflects that it was composed of individuals who possessed both SCD and SCC scores on the more extreme, and maladaptive, ends of their respective continuums. Thus, these were adults who showed the poorest functioning in terms of their self-concepts and this was also reflected in their relatively poor profiles of PWB.

We also examined whether the assignment of men and women and different age groups varied across the SCD-SCC clusters. Findings showed that men and women were represented in equal numbers in each cluster. The results also showed that older adults were more likely to belong to the self-assured cluster compared to young adults. Conversely, young adults were more likely than older adults to belong to the confused-only or fragmented-only clusters, and more likely than middle-aged adults to belong to the fragmented-only cluster. On the one hand, this finding suggests that young adults are in a formative stage with regard to their self-concept and may still be unclear and incoherent about some aspects of their identity. Such an interpretation is consistent with the concept of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000, Arnett & Tanner, 2006), which suggests that the transition from youth to adulthood has become increasingly stretched out and has increased in terms of relational and psychological complexity for recent birth cohorts. Furthermore, these findings suggest that even if adults’ SCC scores tend to plateau or decline somewhat in later adulthood as Lodi-Smith and Roberts’ (2010) have shown, the joint effect of SCD and SCC is such that chronological age and age-related experiences appear to be conducive to the formation of more coherent and more clearly defined self-representations.

In contrast to previous research (Diehl et al., 2001), the data did not support the expectation that certain SCD-SCC structures were more, or less, adaptive at particular points of the adult lifespan. That is, age group did not moderate the association between SCD-SCC clusters and indicators of PWB. Rather, possessing a coherent and clearly defined self-concept was associated with greater positive and lower negative PWB for all age groups. Similarly, having a fragmented self-concept appeared to be associated with poor psychological outcomes at all ages, particularly when combined with a lack of clarity of the self-concept.

It is important to note that such findings do not go against propositions postulating that the self-concept represents an important psychological resource for coping with the challenges of adult development and aging (Brandtstädter & Greve, 1994; Freund & Smith, 1999; Markus & Herzog, 1991). Indeed, our findings are in keeping with the argument that having coherent and clearly defined self-representations may provide an aging person with the multifaceted and dynamic self-understanding that lends his or her life meaning and gives organization to the often diverse thoughts, feelings, and actions that accompany the process of growing older (Labouvie-Vief, 2006; Markus & Herzog, 1991). Our findings, however, suggest that such propositions may hold across all of adulthood. That is, having a coherent and clearly defined self-concept seems to serve equally well as a psychological resource for adults of all ages. In essence, findings from this study suggest that although having a fragmented and unclear self-concept seems to be more common in younger adulthood, it is not less maladaptive in later adulthood than it is in earlier adulthood.

Limitations

Despite adding to our knowledge of how different structural aspects of adults’ self-concept jointly play a role in PWB, this study has some limitations. The main limitation reflects the relatively psychologically well functioning nature of the study sample. Specifically, our sample included adults who were physically and cognitively able to participate in a fairly rigorous daily diary study. Thus, the participants in this study represent adults who are quite physically and psychologically well functioning and who were highly motivated to participate in research. Notably, participants had been screened for depressive symptoms and a history of mental health problems. Given age differences in the prevalence of depression (Kessler, McGonagle, Nelson, Hughes, Swartz, & Blazer, 1994), by screening out participants with potential depression, the skewing of the sample toward containing mentally healthy adults may be most profound among the older adults. Thus, it is likely that our findings are biased and underestimate the proportion of older adults who display some of the less adaptive profiles of SCD-SCC. However, we believe that despite this possible bias the findings from the current study are a valid contribution to the growing literature on the role of self-concept structures in psychological adjustment across the adult lifespan (Diehl, 2006).

GENERAL CONCLUSION

The present study contributes to the literature on the relation between self-concept structure and PWB in adulthood in several ways. First, we demonstrated that categorizing individuals based on their SCD and SCC scores resulted in theoretically meaningful clusters. Moreover, the identified clusters showed theoretically meaningful patterns of mean differences on measures of positive and negative PWB. In particular, we documented that the effect held for multiple dimensions of positive PWB (Ryff & Singer, 1998) and showed an inverse pattern for measures of negative PWB. These findings extend the existing research on the relation between self-concept structure and psychological adjustment (Campbell et al., 2003) which has often relied on very homogeneous samples of young adults (i.e., college students) and fairly narrow operationalizations of PWB.

Second, findings from the current study also contribute to the debate regarding the specialization vs. fragmentation hypothesis (Donahue et al., 1993; Gergen, 1991). Like earlier studies, data from the present study failed to support the specialization hypothesis. Specifically, the cluster analysis failed to identify a cluster of socially specialized individuals (i.e., individuals with high SCD and high SCC). Rather, our data suggest that a coherent and clearly defined self-concept (i.e., the self-assured group) tends to be associated with the most favorable outcomes in terms of PWB.

Finally, our data also provided evidence in support of a positive association between age and self-concept coherence. Although self-concept research with adults of all ages is fairly rare, this result is consistent with theorizing suggesting that adults’ self-concept may be intricately linked to how they negotiate the many challenges associated with growing older (Brandtstädter & Greve, 1994; Labouvie-Vief, 2006; Markus & Herzog, 1991).

Footnotes

The presented research was supported by grant R01 AG21147 from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

We use the terms self-representations and self-concept interchangeably to refer to those attributes or characteristics that are (a) part of a person’s self-understanding and self-knowledge, (b) the focus of self-reflection, and (c) consciously acknowledged by the person through language or other means of communication (see Harter, 1999).

Findings from Bigler et al. (2001) suggested that adopting a regression approach to examining the joint effects of SCD and SCC might not be the best strategy to assess their joint effect. Also, because we assumed that SCD and SCC may interact with each other in a non-linear fashion, multiple regression analysis would not be the most appropriate method to address this question and identify groups of adults with SCC-SCD configurations that might exist in relatively low frequencies, such as a socially specialized group. Thus, to identify conceptually meaningful and qualitatively distinct subgroups, we turned to a taxometric method, namely cluster analysis, for our objective.

It should also be noted that the MANOVAs yielded main effects of age group. However, given that we were primarily interested in the role of age group as a moderator of the association between SCD-SCC cluster and psychological well-being, we do not report the main effects of age group here. A summary describing the age group differences in PWB is available from the first author on request.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Text revision. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler M, Neimeyer GJ, Brown E. The divided self revisited: Effects of self-concept clarity and self-concept differentiation on psychological adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2001;20:396–415. doi: 10.1521/jscp.20.3.396.22302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Block J. Ego-identity, role variability, and adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1961;25:392–397. doi: 10.1037/h0042979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J, Greve W. The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Developmental Review. 1994;14:52–80. doi: 10.1006/drev.1994.1003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Assanand S, DiPaula A. The structure of the self-concept and its relations to psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:115–140. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.t01-0-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Trapnell PD, Heine SJ, Katz IM, Lavallee LF, Lehman DR. Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:141–156. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. NEO PI-R: Revised NEO Personality Inventory and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Damon W, Hart D. Self-understanding in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M. Development of self-representations in adulthood. In: Mroczek D, Little T, editors. Handbook of personality development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 373–398. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Hay EL. Contextualized self-representations in adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2007;75:1255–1283. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Hay EL. Risk and resilience factors in coping with daily stress in adulthood: The role of age, self-concept incoherence, and personal control. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(5):1132–1146. doi: 10.1037/a0019937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Hastings CT, Stanton JM. Self-concept differentiation across the adult life span. Psychology and Aging. 2001;16:643–654. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.16.4.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Youngblade LM, Hay EL, Chui H. The development of self-representations across the lifespan. In: Fingerman KL, Berg CA, Smith J, Antonucci TC, editors. Handbook of lifespan psychology. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 611–646. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue EM, Robins RW, Roberts BW, John OP. The divided self: Concurrent and longitudinal effects of psychological adjustment and social roles on self-concept differentiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:834–846. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Freund AM, Smith J. Content and function of the self-definition in old and very old age. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1999;54B:55–67. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.1.p55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Games PA, Howell JF. Pairwise multiple comparison procedures with unequal n’s and/or variances: A Monte Carlo study. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1976;1:113–125. doi: 10.2307/1164979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gergen KJ. The saturated self: Dilemmas of identity in contemporary life. New York: Basic Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Black WC. Cluster analysis. In: Grimm LG, Yarnold PR, editors. Reading and understanding more multivariate statistics. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. pp. 147–206. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The development of self-representations. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 5. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 553–617. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Developmental and individual difference perspective on self-esteem. In: Mroczek DK, Little TD, editors. Handbook of personality development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 311–334. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S, Monsour A. Developmental analysis of conflict caused by opposing attributes in the adolescent self-portrait. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:251–260. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.28.2.251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haselager G, Cillessen AHN, Van Lieshout CFM, Riksen-Walraven JMA, Hartup WW. Heterogeneity among peer-rejected boys across middle childhood: Developmental pathways of social behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:446–456. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.3.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. Cluster analysis in family psychology research. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:121–132. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W. The principles of psychology. Vol. 1. New York: Holt; 1890/1963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Swartz M, Blazer DG. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey, II: Cohort effects. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1994;30:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43:207–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie-Vief G. Emerging structures of adult thought. In: Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 59–84. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie-Vief G, Chiodo LM, Goguen LA, Diehl M, Orwoll L. Representations of self across the life span. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:404–415. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.10.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME. Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:305–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linville PW. Self-complexity as a cognitive buffer against stress-related illness and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:663–676. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H. Social network type and morale in old age. Gerontologist. 2001;41:516–24. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodi-Smith J, Roberts BW. Getting to know me: Social role experiences and age differences in self-concept clarity during adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2010;78:1383–1410. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:19–40. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandara J, Murray CB. Effects of parental marital status, income, and family functioning on African American adolescent self-esteem. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:475–490. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.14.3.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Identity in adolescence. In: Adelson J, editor. Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York: Wiley; 1980. pp. 159–187. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Herzog RA. The role of the self-concept in aging. In: Schaie KW, editor. Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics. Vol. 11. New York: Springer; 1991. pp. 110–143. [Google Scholar]

- Meehl PE. Factors and taxa, traits and types, differences of degree and differences in kind. Journal of Personality. 1992;60:117–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00269.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan GW, Cooper MC. A study of standardization of variables in cluster-analysis. Journal of Classification. 1988;5:181–204. doi: 10.1007/BF01897163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Shoda Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review. 1995;102:246–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-29X.102.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montemayor R, Eisen M. The development of self-conceptions from childhood to adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1977;13:314–319. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.13.4.314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C. A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships, as developed in the client-centered framework. In: Koch S, editor. Psychology: A study of science. Vol. 3. Formulations of the person and the social context. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1959. pp. 184–256. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Self-concept from middle childhood through adolescence. In: Suls J, Greenwald AG, editors. Psychological perspectives on the self. Vol. 3. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1986. pp. 182–205. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:99–104. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer B. The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:1–28. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0901_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Brennan KA. Measures of depression and loneliness. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS, editors. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. Vol. 1. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 195–289. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM, Ryan RM, Rawsthorne LJ, Ilardi B. Trait self and true self: Cross-role variation in the big-five personality traits and its relations with psychological authenticity and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1380–1393. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Showers CJ, Abramson LY, Hogan ME. The dynamic self: How the content and structure of the self-concept change with mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:478–493. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller NG, Meehl PE. Multivariate taxometric procedures: Distinguishing types from continua. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman AS, Archer SL. A life-span perspective on identity formation: Developments in form, function, and process. In: Baltes PB, Featherman DL, Lerner RM, editors. Life-span development and behavior. Vol. 10. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 29–57. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Tellegen A. Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:219–235. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]