Abstract

Despite conventional treatment strategies glioblastoma, the most common malignant primary brain has a bad prognosis with median survival times of 12-15 month. In this study, the efficacy of sorafenib (Nexavar, BAY43-9006), a multikinase inhibitor, on glioblastoma cells was evaluated both in vitro and in vivo. Treatment of established or patient-derived glioblastoma cells with low concentrations of sorafenib caused a dramatic dose dependent inhibition of proliferation (IC50, 1.5 uM) and induction of apoptosis and autophagy. Sorafenib inhibited phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) and expression of cyclins, D and E. In contrast, AKT was not modulated by sorafenib. Most important, systemic delivery of Sorafenib was well tolerated, and significantly suppressed intracranial glioma growth via inhibition of cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis and autophagy, and reduction of angiogenesis. Furthermore, intracranial growth inhibition by sorafenib was accompanied by a significant reduction in ph-Stat3 (Tyr 705) levels. In summary, sorafenib has potent anti-glioma activity in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: Glioma, Sorafenib, Stat3, apoptosis, autophagy

Introduction

Glioblastoma (WHO IV) is the most commonly diagnosed malignant adult primary brain tumor. Median survival for glioblastoma (GBM) is 12 to 15 months. Current treatment of glioblastoma includes surgical resection or diagnostic biopsy and continues with adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy [1, 7].

Sorafenib (Nexavar, BAY43-9006) is a multikinase inhibitor that been shown to inhibit tumor growth by inhibition of serine/threonine kinases, e.g. c-RAF, and mutant and wild-type BRAF as well as the receptor tyrosine kinases vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), VEGFR3, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), FLT3, Ret, and c-KIT [14, 24-26]. Recently, sorafenib has also been shown to inhibit JAK/STAT (STAT3) signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo [3]. With regards to glioblastoma, STAT3 signaling is important for the growth of U87 xenografts [5]. In Phase I and II clinical trials, sorafenib was well tolerated and even showed promising anti-cancer activity on several types of advanced solid tumors [2, 15].

With respect to GBM, it is unknown whether sorafenib is also effective in treating GBM grown in an orthotopic microenvironment.

These present findings show that sorafenib inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis and autophagy in glioma cells. Importantly, sorafenib inhibited tumor growth in an orthotopic model of glioblastoma in nude mice.

Cells, cell cultures and reagents

Human glioblastoma cell lines LN229 (mutant p53, wild type PTEN), U87 (wild-type p53, mutant PTEN), U251 (mutant p53) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Patient-derived, primary cultures of glioblastoma cells (GS620, GS48 and AS515) were established by dissecting tissues in small pieces and transferring to plastic tissue culture flasks (Falcon, Becton Dickinson). Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C, with 5% CO2. Cells were grown to confluence with medium changes biweekly and were harvested by a brief incubation with trypsin/EDTA solution (Viralex, PAA). The glial origin of these cultures was confirmed by staining for α-glial fibrillary acidic protein (Dako), whereas antibodies against endothelial cell markers, CD31 (PharMingen) or factor VIII (Dako), or neuronal neurofilament proteins 70, 160, and 200 (all from Progen), were unreactive. Sorafenib was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA) and dissolved in DMSO for in vitro studies. A maximum dose of 0.1% DMSO was never exceeded. For in vivo application sorafenib was dissolved in a solution consisting of cremophor and ethanol as described [3].

Immunoblotting and Antibodies

Cellular extracts were prepared in a lysis buffer containing 20 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.5), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton, 0.1% SDS, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 50 mmol/L NaF, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, plus protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Lysates were separated by SDS gel electrophoresis and transferred to Immobilon membranes (Millipore). Antibodies to LC3, Beclin-1 (1:1000, CST Inc., Danvers, MA), Bcl-2 (1:1000, CST. Inc., Danvers, MA), survivin (1:1000, NOVUS Biologicals, Littleton, CO), XIAP (1:1000 BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ), Ser 473-phosphorylated Akt (1:500, CST. Inc., Danvers, MA), ph-Stat3 (1:500, CST. Inc., Danvers, MA) and Stat3 (1:500, CST. Inc., Danvers, MA) and Akt (1:1000, CST. Inc., Danvers, MA) were used.

Apoptosis and autophagy

The various cell types were seeded in triplicates onto 96-well plates at 2×103 cells/well, treated with Sorafenib for up to 24 h, and analyzed for metabolic activity by an MTT, 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-Yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide, assay, as described [18]. For determination of apoptosis and cell cycle analysis, cells (1×106) were permeabilised with ethanol and subsequently stained with propidium iodide (PI) (BD Bioscience, USA). For characterization of autophagy, glioblastoma cells were transfected with an LC3-GFP cDNA by LipofectAmine, treated with Sorafenib and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. A cell was scored as autophagic when exhibiting a punctate GFP labeling with >10 LC3-GFP dots/cell. An average of 200 cells was counted in 4-6 independent fields per condition.

Preclinical glioblastoma models

All experiments involving animals were approved by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Experiments were carried out in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC), or the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23) revised 1996, or the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. U87 glioblastoma cells stably transfected with a luciferase expression plasmid (U87-Luc) were suspended in sterile PBS, pH 7.4, and stereotactically implanted (1×105) in the right cerebral striatum of immunocompromised NIH Nu/Nu female mice (Charles River Laboratories). Animals with established tumors were randomized in two groups (n=4; 8 animals per group), and started on day 8 after implantation on sterile vehicle (PBS, pH 7.2), or Sorafenib (100 mg/kg as daily i.p. injections) for 17 consecutive days. Tumor growth was assessed weekly after i.p injection of 58 mg/kg D-luciferin by bioluminescence imaging using a Xenogen In Vivo Imaging System. In some experiments animals were harvested on day 21 and subjected to histological analysis. Brain samples from the various animal groups were stained with H&E or with antibodies to Ki-67 (Zymed) or CD31 (Becton Dicksinson) or LC-3 (CST, Inc, Danvers, MA) as described [10]. For in situ determination of apoptosis, brain sections were analyzed for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL, Roche). Images were collected on an Olympus microscope with on-line charge-coupled device camera. Microvessel density in CD31-stained sections was determined using an image analysis algorithm (S. CO LifeScience Co., Garching, Germany), as described [8].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by two-sided unpaired t-tests using a GraphPad software package (Prism 4.0) for Windows. A p value of 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Values are expressed as means of triplicate or duplicate experiments. For preclinical studies, the mean and SEM were calculated with mice as the data units.

Results and discussion

Sorafenib inhibits cellular proliferation in both established and primary glioblastoma cells

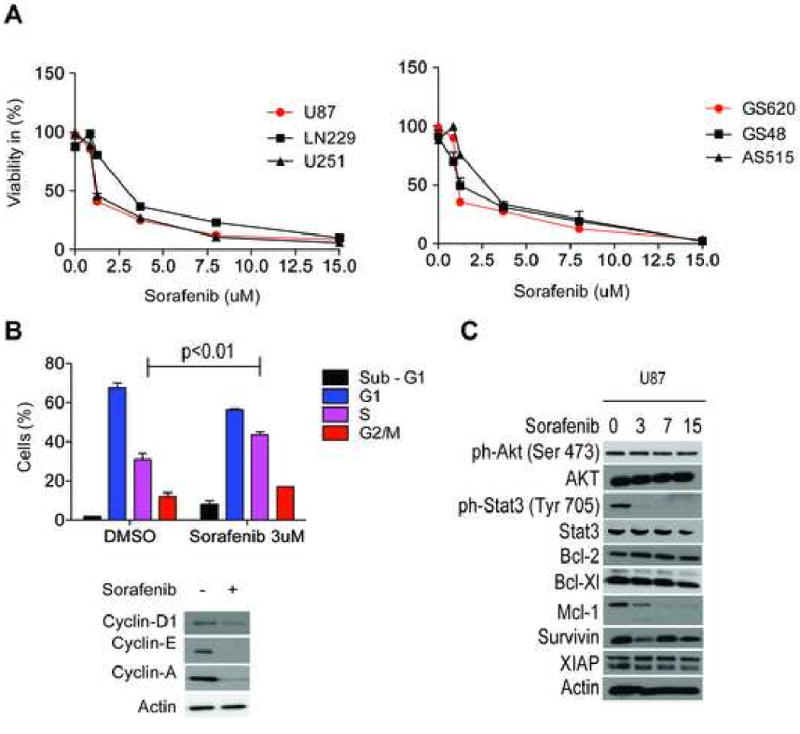

Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of sorafenib (1.25-15 uM) and analysed by MTT-assay after 24 hours (Figure 1A). Both established and primary glioblastoma cells showed a comparable sensitivity to sorafenib (IC50: 1-2 uM). Furthermore, sorafenib inhibited proliferation of tumor cells independent of their genetic background. LN229 (p53-mutant, PTEN wild-type) and U87 (p53 wild-type, PTEN mutant) exhibited the same response to sorafenib, suggesting that sorafenib acts on glioblastoma cells independent of p53 and PTEN status. Notably, primary glioblastoma cells, which more closely resemble the genetic background of glioblastoma specimens [13], were equally sensitive to sorafenib as compared to established glioblastoma cells (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Sorafenib inhibits tumor cell proliferation, alters cell cycle distribution in U87 cells, suppresses the expression of cyclins in U87 cells and modulates ph-STAT3 (Tyr 705) and Mcl-1 protein levels in U87 cells. A, Cellular proliferation assessed by MTT assay in U87, LN229, U251, AS515, GS48 and GS620 glioblastoma cells. B, Cell cycle analysis of U87 treated with sorafenib for 48 hours. Immunoblot analysis of Cylin-D1,E and A in U87 cells treated with 3 uM Sorafenib for 48 hours. D, Immunoblot analysis of ph-Akt (Ser 473), Akt, ph-Stat3 (Tyr 705), Stat3, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, Survivin and XIAP in U87 cells treated with increasing concentrations of sorafenib (0-15 uM) for 24 hours. The highest dose of DMSO used in this study was 0.1% and all treatments with 0 uM sorafenib were performed in the presence of 0.1% DMSO. Data are mean±SEM.

Sorafenib inhibits expression of Cyclin-D, -E and -A

Since sorafenib significantly inhibits proliferation of glioblastoma cells, the effect of sorafenib on key cell-cyle regulators, including D, E, A-type cyclins, was investigated. Immunoblot analysis revealed that Cyclin D, E and A were significantly reduced after 24 hours after treatment with sorafenib (Figure 1B). Next, cell cycle distribution in U87 glioma cells was analysed by propidium iodide staining. Figure 1B shows a decrease of cells in G1 phase and an increase of cells arrested in S phase (p<0.01) after treatment with sorafenib. The reduction of cyclin D and E is consistent with the S-phase arrest that is also in line with a previous report demonstrating that sorafenib induced an S-phase arrest in primary medulloblastoma cells [25].

Sorafenib inhibits phosphorylation of STAT3, but does not modulate the Akt-pathway

Stat3 has an important role in glioblastoma and participates in regulation of proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis and is a key mediator in glioblastoma immunosuppression [4, 19, 23]. Since Sorafenib has shown to modulate STAT3 in other tumor entities [3] expression of ph-Stat3 (Tyr 705) and STAT3 were determined by immunoblot. Increasing concentrations of sorafenib led to a significant dephosphorylation of Stat3 whereas the total form of STAT3 did not change significantly (Figure 1C). The PI3K/AKT pathway is of major significance in the pathophysiology of glioblastoma and drugs that are capable of inhibiting this pathway might be useful in the treatment of glioblastoma. However, sorafenib neither changed ph-Akt (Ser 473) nor Akt levels (Figure 1 C). As glioblastomas reveal an endogenous resistance against apoptosis [12] that is at least partially mediated by certain key anti-apoptotic proteins, e.g. Bcl-2 family and the Inhibitor of Apoptosis proteins (IAP), modulation of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Mcl-1, survivin and XIAP protein levels were determined. Out of these major anti-apoptotic proteins, Mcl-1 was significantly down-regulated by sorafenib (Figure 1C) and this suppression correlated with cell death in U87 glioblastoma cells (Figure 2A). In previous studies it has been well established that sorafenib leads to a reduction of Mcl-1 protein levels in cancer cells [3, 21].

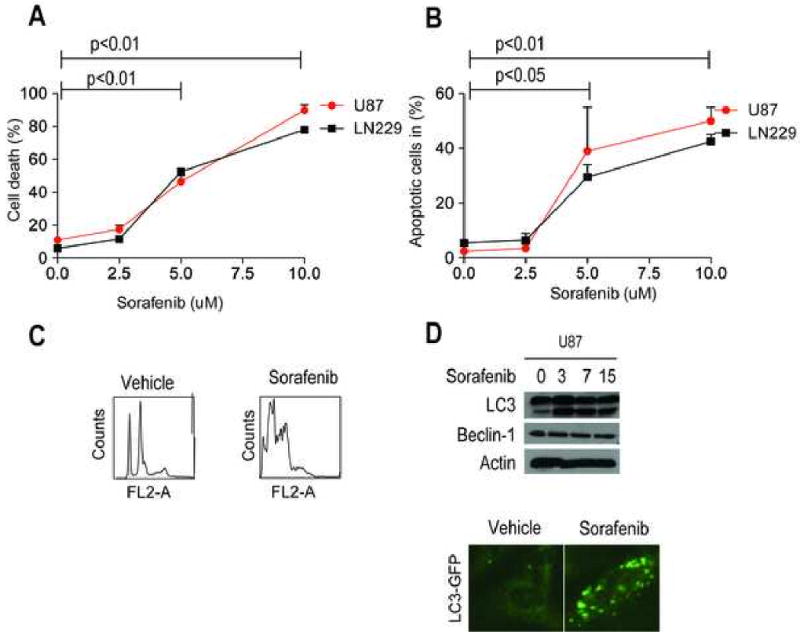

Figure 2.

Induction of a dual-type of cell death by sorafenib. A, Quantification of cell death in U87 and LN229 cells by trypan blue staining after increasing concentrations with sorafenib. B, Quantification of U87 and LN229 cells in sub-G1 fraction after PI-staining. C, Representative images of Propidium iodide after treatment with Sorafenib. D, U251 cells transfected with LC3-GFP cDNA were treated with sorafenib, and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. S2.5/5.0/10: Sorafenib 2.5/5/10 uM. Data are mean±SEM.

Sorafenib induces a dual type of cell death in glioblastoma cells

To determine whether sorafenib is also capable of killing glioblastoma cells trypan blue staining was carried out 24 hours after treatment with increasing concentrations of sorafenib. There was a significant increase in cell death (5 uM and 10 uM) compared to the untreated control (Figure 2A). Next, the amount of apoptotic cells was determined by propidium iodide staining. Treatment with increasing concentrations of sorafenib increased the sub-G1 (apoptotic fraction) in U87 and LN229 glioblastoma cells (Figure 2B). A representative example of this analysis is provided as part of figure 2C. In addition, sorafenib-treated glioblastoma cells exhibited biochemical markers of autophagy with appearance of a lipidated, faster migrating form of the ubiquitin-like protein, LC3 (Figure 2D), which is involved in autophagosome formation [9]. This was associated with a punctate pattern of LC3-GFP labeling (Fig. 2D), characteristic of autophagy [9], in Sorafenib-treated cells. However, Beclin-1 levels were not changed in sorafenib-treated cells (Figure 2D).

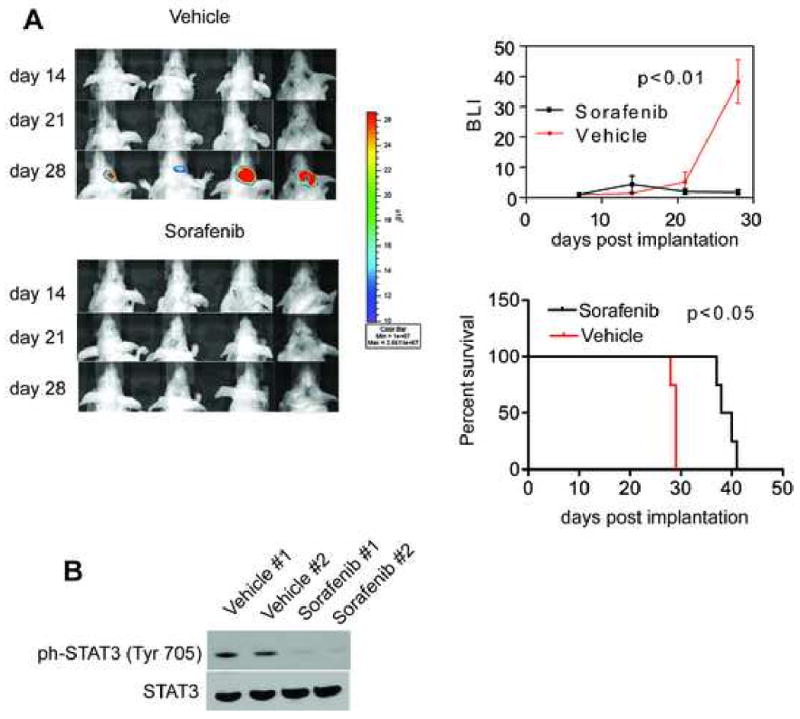

Sorafenib suppresses glioma growth, in vivo

Stereotactic implantation of U87-Luc glioblastoma cells in the right cerebral striatum of immunocompromised mice gave rise to exponentially growing tumors, by bioluminescence imaging (Fig. 3A). Systemic administration of Sorafenib to these mice suppressed intracranial glioma growth, in vivo, as assessed by bioluminescence imaging (Fig. 3A). At day 28 post implantation, sorafenib-treated animals showed a significant reduction in bioluminescence (p<0.01). Systemic treatment with sorafenib was not associated with systemic or organ toxicity, and did not result in animal weight loss throughout treatment. In addition, animal survival was significantly prolonged in sorafenib-treated animals (p<0.05) (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Anti-glioma activity of Sorafenib, in vivo. A, NIH Nu/Nu mice stereotactically implanted with U87-Luc cells in the right cerebral striatum were treated systemically with vehicle or Sorafenib (100 mg/kg daily i.p.), and imaged by live bioluminescence at the indicated time intervals. Treatment was initiated after 7 days of tumor cell implantation and stopped by day 25. Representative animals per group are shown. Right, quantification of bioluminescence units (BLI) and survival curves in vehicle or Sorafenib-treated groups. Data are the mean±SD of the various groups (4 animals/group). B, Immunoblots of two vehicle and two sorafenib-treated animals showing ph-Stat3 (Tyr 705) and total Stat3 protein levels (100 mg/kg daily i.p.). Data are the mean±SD of the various groups (4 animals/group). Experiments were performed twice and in both experiments sorafenib treated animals exhibited significantly less BLI than vehicle-treated animals (p<0.01).

This growth inhibition was accompanied by a significant reduction in ph-Stat3 (Tyr 705) levels in orthotopic glioblastoma xenografts, suggesting that Stat3 signalling might be a component in the biological effects of sorafenib (Fig. 3A and 3B). These findings are in line with a recent report that demonstrated that Stat3 is persistently activated in GBM tumours and derived cell lines [5]. Dominant negative-Stat3-expressing clone-derived tumours in the background of the U87 failed to grow beyond 2mm of thickness in mouse flanks [5]. This blockade of tumor growth was associated with induction of tumor cell apoptosis and suppression of tumor angiogenesis [5]. Consistent with this, mice bearing orthotopically implanted dominant negative-Stat3-expressing clones survived significantly longer than the control mice [5].

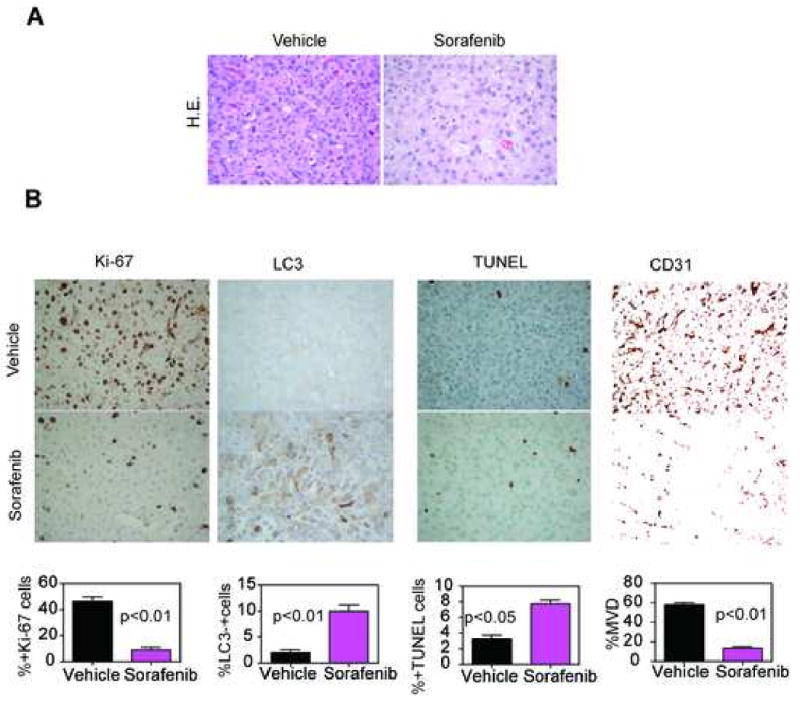

Histologically, intracranial gliomas growing in vehicle-treated mice exhibited an elevated mitotic index, negligible apoptosis and autophagy, and extensive angiogenesis (Fig. 4 A,B). In contrast, brain sections collected from Sorafenib-treated mice revealed significant inhibition of glioblastoma cell proliferation, increased apoptosis and autophagy, and suppression of angiogenesis, in vivo (Fig. 4B). Our report is line with previous reports in which sorafenib inhibits angiogenesis and growth of orthotopic anaplastic thyroid carcinoma xenografts and orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma xenografts in nude mice [11, 22]. Mechanistically, sorafenib has been shown to reduce VEGF production in several tumor xenografts and also to inhibit VEGF receptor signaling [17, 20]. Since Sorafenib inhibits the effects of VEGF and anti-angiogenic therapies with bevacizumab have been shown to force a highly angiogenic, noninvasive orthotopic glioblastoma xenograft tumor to become infiltrative [6] it remains to be determined whether sorafenib might cause a similar phenotype. Treatment of glioblastoma is usually complicated and interfered by the blood-brain barrier, which acts as a physiological barrier for drug delivery. This is the first report demonstrating that sorafenib effectively crosses the blood-brain barrier and inhibits tumor growth in an orthotopic tumor model of glioblastoma. Many promising anti-cancer drugs fell short of expectations because of their pharmacokinetics and properties that does not allow them to cross the blood-brain barrier and reach effective concentration in brain tumors [16]. As combination therapies are promising in glioblastoma, sorafenib might also serve as an adjunct to established chemotherapeutic drugs and/or radiation therapy.

Figure 4.

Histopathology of Sorafenib anti-glioma activity, in vivo. A, representative brain sections from vehicle- or Sorafenib-treated mice were harvested after 28 d, and analyzed by H&E. B, representative brain sections from vehicle- or Sorafenib-treated mice were harvested after 28 d, and analyzed cell proliferation (Ki67), apoptosis (TUNEL), autophagy (LC3) or angiogenesis (CD31), by immunohistochemistry. Magnification, ×400. C, quantification of mitotic index (left), apoptosis and autophagy (middle) and microvessel density (right). Labeled cells were counted in an average of 10-15 high-power fields. Data are mean±SEM.

In summary, we have demonstrated that sorafenib has potent anti-glioma activity in vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Drs. Eric Baehrecke and Claire-Marie Sauvageot for reagents and Kathryn Chase and Neil Aronin for providing the stereotactical frames.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant, Si 1546/1-1 (MDS) and the National Cancer Institute of Health (NIH) grants, CA78810, CA90917 and CA118005

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abou-Alfa GK. Selection of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma for sorafenib. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:397–403. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blechacz BR, Smoot RL, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Sirica AE, Gores GJ. Sorafenib inhibits signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 signaling in cholangiocarcinoma cells by activating the phosphatase shatterproof 2. Hepatology. 2009;50:1861–1870. doi: 10.1002/hep.23214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brantley EC, Nabors LB, Gillespie GY, Choi YH, Palmer CA, Harrison K, Roarty K, Benveniste EN. Loss of protein inhibitors of activated STAT-3 expression in glioblastoma multiforme tumors: implications for STAT-3 activation and gene expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4694–4704. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dasgupta A, Raychaudhuri B, Haqqi T, Prayson R, Van Meir EG, Vogelbaum M, Haque SJ. Stat3 activation is required for the growth of U87 cell-derived tumours in mice. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:677–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Groot JF, Fuller G, Kumar AJ, Piao Y, Eterovic K, Ji Y, Conrad CA. Tumor invasion after treatment of glioblastoma with bevacizumab: radiographic and pathologic correlation in humans and mice. Neuro Oncol. 12:233–242. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehdashti AR, Hegi ME, Regli L, Pica A, Stupp R. New trends in the medical management of glioblastoma multiforme: the role of temozolomide chemotherapy. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E6. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaiser T, Becker MR, Meyer J, Habel A, Siegelin MD. p53-mediated inhibition of angiogenesis in diffuse low-grade astrocytomas. Neurochem Int. 2009;54:458–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang H, White EJ, Conrad C, Gomez-Manzano C, Fueyo J. Autophagy pathways in glioblastoma. Methods Enzymol. 2009;453:273–286. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang BH, Plescia J, Song HY, Meli M, Colombo G, Beebe K, Scroggins B, Neckers L, Altieri DC. Combinatorial drug design targeting multiple cancer signaling networks controlled by mitochondrial Hsp90. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:454–464. doi: 10.1172/JCI37613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S, Yazici YD, Calzada G, Wang ZY, Younes MN, Jasser SA, El-Naggar AK, Myers JN. Sorafenib inhibits the angiogenesis and growth of orthotopic anaplastic thyroid carcinoma xenografts in nude mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1785–1792. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lefranc F, Brotchi J, Kiss R. Possible future issues in the treatment of glioblastomas: special emphasis on cell migration and the resistance of migrating glioblastoma cells to apoptosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2411–2422. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li A, Walling J, Kotliarov Y, Center A, Steed ME, Ahn SJ, Rosenblum M, Mikkelsen T, Zenklusen JC, Fine HA. Genomic changes and gene expression profiles reveal that established glioma cell lines are poorly representative of primary human gliomas. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:21–30. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu L, Cao Y, Chen C, Zhang X, McNabola A, Wilkie D, Wilhelm S, Lynch M, Carter C. Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11851–11858. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller AA, Murry DJ, Owzar K, Hollis DR, Kennedy EB, Abou-Alfa G, Desai A, Hwang J, Villalona-Calero MA, Dees EC, Lewis LD, Fakih MG, Edelman MJ, Millard F, Frank RC, Hohl RJ, Ratain MJ. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of sorafenib in patients with hepatic or renal dysfunction: CALGB 60301. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1800–1805. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muldoon LL, Soussain C, Jahnke K, Johanson C, Siegal T, Smith QR, Hall WA, Hynynen K, Senter PD, Peereboom DM, Neuwelt EA. Chemotherapy delivery issues in central nervous system malignancy: a reality check. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2295–2305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.9861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pignochino Y, Grignani G, Cavalloni G, Motta M, Tapparo M, Bruno S, Bottos A, Gammaitoni L, Migliardi G, Camussi G, Alberghini M, Torchio B, Ferrari S, Bussolino F, Fagioli F, Picci P, Aglietta M. Sorafenib blocks tumour growth, angiogenesis and metastatic potential in preclinical models of osteosarcoma through a mechanism potentially involving the inhibition of ERK1/2, MCL-1 and ezrin pathways. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:118. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plescia J, Salz W, Xia F, Pennati M, Zaffaroni N, Daidone MG, Meli M, Dohi T, Fortugno P, Nefedova Y, Gabrilovich DI, Colombo G, Altieri DC. Rational design of shepherdin, a novel anticancer agent. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahaman SO, Harbor PC, Chernova O, Barnett GH, Vogelbaum MA, Haque SJ. Inhibition of constitutively active Stat3 suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in glioblastoma multiforme cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:8404–8413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramakrishnan V, Timm M, Haug JL, Kimlinger TK, Wellik LE, Witzig TE, Rajkumar SV, Adjei AA, Kumar S. Sorafenib, a dual Raf kinase/vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor has significant anti-myeloma activity and synergizes with common anti-myeloma drugs. Oncogene. 29:1190–1202. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosato RR, Almenara JA, Coe S, Grant S. The multikinase inhibitor sorafenib potentiates TRAIL lethality in human leukemia cells in association with Mcl-1 and cFLIPL down-regulation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9490–9500. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Zhou J, Fan J, Qiu SJ, Yu Y, Huang XW, Tang ZY. Effect of rapamycin alone and in combination with sorafenib in an orthotopic model of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5124–5130. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei J, Barr J, Kong LY, Wang Y, Wu A, Sharma AK, Gumin J, Henry V, Colman H, Priebe W, Sawaya R, Lang FF, Heimberger AB. Glioblastoma cancer-initiating cells inhibit T-cell proliferation and effector responses by the signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 pathway. Mol Cancer Ther. 9:67–78. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, Wilkie D, McNabola A, Rong H, Chen C, Zhang X, Vincent P, McHugh M, Cao Y, Shujath J, Gawlak S, Eveleigh D, Rowley B, Liu L, Adnane L, Lynch M, Auclair D, Taylor I, Gedrich R, Voznesensky A, Riedl B, Post LE, Bollag G, Trail PA. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang F, Van Meter TE, Buettner R, Hedvat M, Liang W, Kowolik CM, Mepani N, Mirosevich J, Nam S, Chen MY, Tye G, Kirschbaum M, Jove R. Sorafenib inhibits signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling associated with growth arrest and apoptosis of medulloblastomas. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3519–3526. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu C, Friday BB, Lai JP, Yang L, Sarkaria J, Kay NE, Carter CA, Roberts LR, Kaufmann SH, Adjei AA. Cytotoxic synergy between the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib and the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in vitro: induction of apoptosis through Akt and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathways. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2378–2387. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]