Abstract

Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system. Tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) is recognized as a modulator of glutamatergic neurotransmission. This attribute is exemplified by its ability to potentiate calcium signaling following activation of the glutamate-binding N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR). It has been hypothesized that tPA can directly cleave the NR1 subunit of the NMDAR and thereby potentiate NMDA-induced calcium influx. In contrast, here we show that this increase in NMDAR signaling requires tPA to be proteolytically active, but does not involve cleavage of the NR1 subunit or plasminogen. Rather, we demonstrate that enhancement of NMDAR function by tPA is mediated by a member of the Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor (LDLR) family. Hence, this study proposes a novel functional relationship between tPA, the NMDAR, a LDLR and an unknown substrate which we suspect to be a serpin. Interestingly, whilst tPA alone failed to cleave NR1, cell-surface NMDARs did serve as an efficient and discrete proteolytic target for plasmin. Hence, plasmin and tPA can affect the NMDAR via distinct avenues. Altogether, we find that plasmin directly proteolyses the NMDAR whilst tPA functions as an indirect modulator of NMDA-induced events via LDLR engagement.

Keywords: Tissue-type plasminogen activator, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, Low-density lipoprotein receptor family, Serine protease inhibitor, Plasmin

INTRODUCTION

The serine protease, tPA, is known for its ability to cleave the pro-enzyme plasminogen into the potent protease plasmin, which can in turn lyse blood clots via the digestion of fibrin. In addition to this vascular role, tPA is now recognized to perform important roles within the brain (Samson & Medcalf 2006, Melchor & Strickland 2005). Neurons and glia secrete tPA upon appropriate stimulation (Lochner et al. 2006, Fernandez-Monreal et al. 2004b, Vincent et al. 1998, Polavarapu et al. 2007). Extracellular tPA activity is balanced by inhibitors and spatially targeted by association with cell-surface receptors. tPA−/− mice display cognitive deficits, alterations in addiction and stress, and shifts in the response to pathological situations including seizure and ischemia (Yepes et al. 2002, Wang et al. 1998). Notably, recombinant tPA is used as a thrombolytic agent in patients with ischemic stroke (NINDS 1995). Altogether, a multitude of physiological and pathological roles have been ascribed to tPA. Despite the functional diversity of tPA within the brain, two recurrent themes exist: (i) the physiological actions of tPA are contextual with synaptic plasticity processes; (ii) pathologically, tPA operates as an injurious excitotoxic factor. The paradigms of synaptic plasticity and excitotoxicity are both reliant upon the NMDA receptor (NMDAR). As a result, several recent studies which show interplay between tPA and the NMDAR have received considerable attention (Kvajo et al. 2004, Pawlak et al. 2005a, Nicole et al. 2001, Park et al. 2008, Benchenane et al. 2007, Norris & Strickland 2007, Pawlak et al. 2005b, Martin et al. 2008, Medina et al. 2005).

A persuasive body of evidence suggests that tPA can directly (i.e. in a plasmin-independent manner) cleave the NR1 subunit and thereby increase the Ca2+-permeability of the NMDAR (Nicole et al. 2001, Fernandez-Monreal et al. 2004a, Benchenane et al. 2007). Our previous analyses have demonstrated that tPA does indeed augment NMDA-induced calcium flux (Δ[Ca2+]i; Reddrop et al. 2005). Indicative of a novel effector substrate, here we show that the potentiating effect of tPA is dependent upon its proteolytic activity and independent of plasmin(ogen). Moreover, we find that tPA does not directly cleave the NR1 subunit. Hence, the mechanism by which tPA increases NMDAR signaling appears to be more complicated that first hypothesized. In line with this notion, we show that the ability of tPA to augment NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i requires a member of the Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor (LDLR) family. Thus, the potentiating effect of tPA on NMDAR signaling requires a co-receptor and an unknown substrate. In support of a multi-factorial mechanism, we find that tPA does not alter NMDAR-mediated currents in an expressed heterologous Xenopus oocyte system, suggesting that additional cellular factors present in neuronal cultures are necessary for tPA to modulate NMDAR function. Lastly, distinct from the potentiation of NMDAR function, our analyses uncover the unique capacity of plasmin to discretely cleave the NR1 subunit. Thus, tPA has a dual influence on the NMDAR: one being the indirect potentiation of calcium flux via LDLR engagement, and the other being the plasmin-dependent proteolysis of NR1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57Black/6 mice between 2-6 months old were used in this study. Experiments adhered to NH&MRC of Australia guidelines for live animal use. Experiments were approved by the appropriate Institutional Animal Ethics Committee.

Materials

Unless stipulated all reagents were from Invitrogen. Recombinant human tPA used was Actilyse® (Boehringer Ingelheim). For Fig.1, 2B, 5 and 7 the Actilyse® had been dialysed against 0.35M HEPES-KOH (pH7.4). No difference in the effect of dialysed versus undialysed tPA was seen in this study. Aprotinin, human plasmin, NMDA and MK-801 were obtained from Sigma. Cyanogen bromide-digested human fibrinogen was from American Diagnostica. Human thrombin was from Calbiochem. ctPA was kindly provided by PAION Deutschland GmbH. ctPA was generated from Actilyse® by covalently coupling a 10-fold molar excess of D-phenyl-prolyl-arginine chloromethyl ketone into the reactive centre of the tPA molecule. RAP and anti-human LRP-1 antibody were kind gifts from Prof. Dudley Strickland (University of Maryland, USA). Human LRP-1 was provided by Prof. Phil Hogg (University of New South Wales, Australia). NeuN and GFAP antibodies were donated by Dr Gabriel Liberatore (University of Melbourne, Australia).

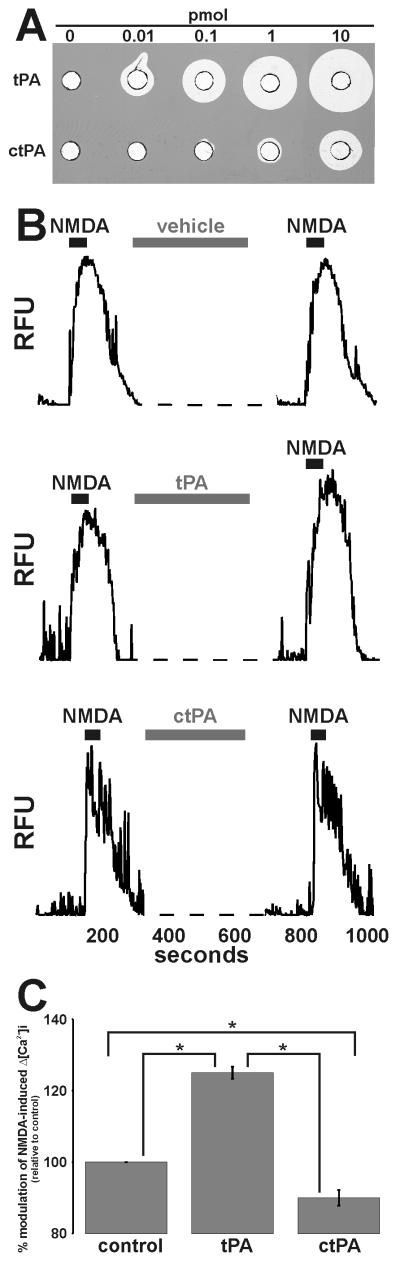

Figure 1. tPA requires its proteolytic activity to potentiate NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i.

Panel A: Increasing amounts of tPA or ctPA were loaded into wells of a fibrin:plasminogen:agarose matrix (Granelli-Piperno & Reich 1978) and incubated at 37°C until proteolyzed zones appeared. Panel B: Representative single cell traces of 25μM NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i before and after 5min perfusion with vehicle, 500nM tPA or 500nM ctPA. Panel C: Collated data demonstrating that 500nM ctPA does not enhance 25μM NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i. Data represents mean ±SEM of the second NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i relative to the first NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i (i.e. % modulation). All data was normalized to control values. The data was pooled from N=61 cells (control), N=84 cells (tPA), N=75 cells (ctPA) over three independent cultures (n=3; * p<0.05).

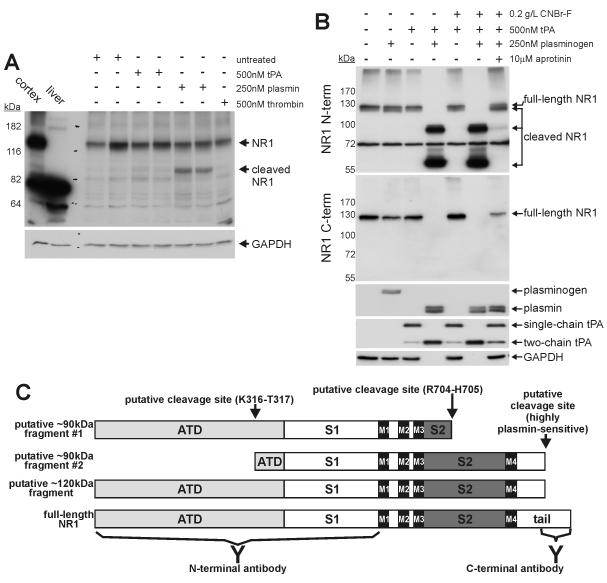

Figure 2. The NR1 subunit of the NMDAR is a substrate for plasmin, but not tPA.

Panel A: Representative cell-based cleavage assay demonstrating that plasmin, but not tPA, can cleave the NR1 subunit of the NMDAR. Cultures were incubated with 500nM tPA, 250nM plasmin or 500nM thrombin at 37°C for 10min. The NR1 content was assessed by immunoblot using the anti-NR1 N-terminal antibody. The membrane was re-probed for GAPDH as a loading control. A total of 6 independent cell-free cleavage assays demonstrated that tPA cannot cleave the NR1 subunit (n=6). Note, the anti-NR1 N-terminal antibody is a “pan” antibody as it recognizes all NR1 variants. Panel B: Representative cell-free cleavage assay demonstrating that plasmin, but not tPA, can cleave the NR1 subunit. tPA−/− mouse cortical lysates were supplemented with CNBr-F, 500nM tPA, plasminogen and aprotinin and incubated at 37°C for 15min. The NR1 content was assessed by immunoblot using both anti-NR1 N-terminal and C-terminal antibodies. To assess the proteolytic actions of tPA and plasmin, membranes were re-probed for plasmin(ogen) and tPA, respectively. The membranes were re-probed for GAPDH as a loading control. Note, the generation of plasmin under cell-free conditions leads to a loss of GAPDH, presumably as a consequence of proteolytic degradation. A total of 7 independent cell-free cleavage assays demonstrate that plasmin, but not tPA, can cleave the NR1 subunit (n=7). Panel C: The NR1 subunit is comprised of an amino-terminal domain (ATD), a bi-lobed ligand binding domain (S1 and S2), four transmembrane segments (M1-M4) and a C-terminal tail. Note, the anti-NR1 N-terminal antibody is raised against the ATD and S1 regions of NR1, whilst the anti-C-terminal antibody is raised against the C-terminal tail. Our cell based cleavage assays indicate that a 90kDa fragment is generated from the naturally presented NR1 molecule, while additional fragments of 120 and 60kDa are generated when cryptic cleavage sites are exposed following cell disruption (i.e. as seen using the cell free cleavage assay). The schematic indicates how these fragments may be generated from the native NR1 molecule. It appears that a highly-plasmin sensitive cleavage site resides near the C-terminus of NR1. Proteolysis at this point yields the 120kDa fragment. The 120kDa fragment is further proteolysed into a 90kDa and a 60kDa fragment that are recognized solely by the N-terminal antibody. Proteolytic generation of the 90kDa fragment is best explained by cleavage at one of two putative cleavage sites: (1) a site within the S2 domain yielding “fragment #1”, or (2) a site within the ATD yielding “fragment #2. The specific cleavage site yielding the 60kDa fragment is unclear and is not shown in the diagram.

Several studies have determined the site specificity of plasmin (Harris et al. 2000, Backes et al. 2000, Gosalia et al. 2005, Xue & Seto 2005). This consensus substrate specificity was used to scan the S2 domain for putative plasmin-sensitive cleavage sites. Any putative cleavage sites were then located within the crystal structure of the NR1:NR2A dimeric complex (PDB Identifier # 2A5T) to ensure surface exposure. Via this method, Arginine704-Histidine705 was highlighted as a putative plasmin-sensitive cleavage site with the S2 domain. Using a similar approach, Lysine316-Tyrosine317 was identified as a putative plasmin-sensitive cleavage site with the ATD. In this instance, as the crystal structure of the NR1 ATD has not be resolved, the ATD of the closely related mGluR1 was used (PDB Identifier # 1EWK; (Huggins & Grant 2005)).

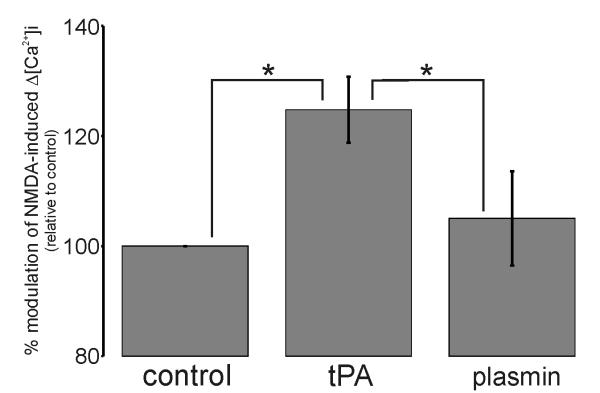

Figure 5. tPA potentiates NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i in a plasmin-independent manner.

Collated data demonstrating that unlike 500nM tPA, 25nM plasmin fails to potentiate 25μM NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i. Data represents mean ±SEM of the second NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i relative to the first NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i (i.e. % modulation). All data was normalized to control values. The data was pooled from N=134 cells (control), N=64 cells (tPA) and N=66 cells (plasmin) over three independent cultures (n=3; * p<0.05).

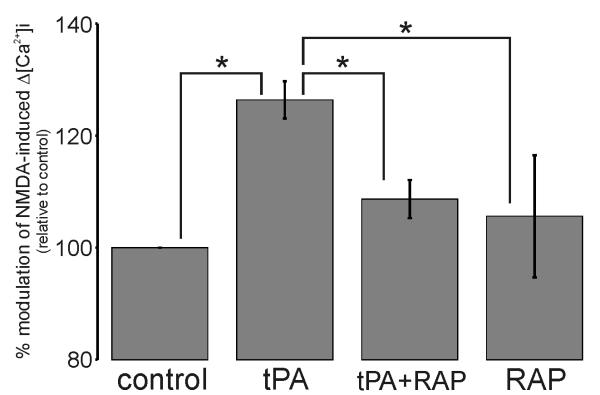

Figure 7. A Low-Density Lipoprotein receptor mediates the tPA potentiation of 50μM NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i.

Collated data demonstrating potentiation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i by 500nM tPA and the ability 500nM RAP to block this effect. Data represents mean ±SEM of the second NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i relative to the first NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i (i.e. % modulation). All data was normalized to control values. The data was pooled from N=83 cells (control), N=78 cells (tPA), N=64 cells (tPA+RAP) and N=55 cells (RAP) over three independent cultures (n=3; * p<0.05).

Preparation of primary cortical neuron cultures

Cultures were prepared from E15-16 mice (Reddrop et al. 2005). In brief, cortices were removed in ice-cold HBSS+: Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution with 1mM Na pyruvate, 10mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.3), 3g/L BSA and 1.2mM MgSO4. The isolated cortices were centrifuged (900×g, 5min, 4°C), supernatant discarded, and tissue pellet incubated in HBSS+ with 0.2g/L trypsin and 80U/ml DNase I (5min, 37°C with agitation). Trypsinization was stopped by the addition of HBSS+ with 0.5g/L trypsin inhibitor, centrifuged (900×g, 5min, 4°C), the supernatant discarded and 10ml of HBSS+ with 0.5g/L trypsin inhibitor and 2.1mM MgSO4 was added. The pellet was triturated through an 18-gauge blunt-ended needle. The resultant single cell suspension was centrifuged (900×g, 5min, 4°C) and the pellet resuspended in Neurobasal media with 1xB27, 10% dialysed fetal calf serum, 0.5mM L-glutamine and 50U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). The cell suspension was seeded onto poly-D-lysine (BD Bioscience) coated 24- or 12-well plates (±glass coverslips) at 150,000 cells/cm2 and maintained in a humidified 37°C incubator under 5% CO2 and 8% O2. 24 hours after seeding (DIV1; “days in vitro”), the serum-containing media was aspirated and replaced with NBM+ media (Neurobasal media with 1.25xB27, 0.5mM L-glutamine and 50U/ml P/S). At DIV5, an equal volume of NBM+ media was added. All experiments were performed with either DIV5 or DIV12-13 cultures (as indicated) in a humidified 37°C incubator under 5% CO2, 20% O2. Suppl. Fig.S5 demonstrates the cellular constituents of these cultures.

Measurement of Δ[Ca2+]i

Neurons cultured on coverslips were incubated in phenol red-free NBM+ media containing 1μM Oregon Green® 488 BAPTA-1 AM, for 45min at 37°C. The media was replaced with fluorophore-free NBM+ media and incubated for a further 45min. The coverslips were then assembled into a perfusion chamber (Warner Instruments Model RC-20H) on the stage of a Leica DM-IRBE confocal microscope which was encased in a Perspex incubator and held at 37°C by an electric air heater. A single field of neurons (typically 15-30 neurons) was selected and Flow Buffer (phenol red-free HBSS with 2mM CaCl2 and 0.6mM MgCl2) perfused over the cells at 0.5ml/min. For the assessment of the modulation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i, a perfusion protocol involving three stimulations was employed. Δ[Ca2+]i was monitored in 1.8 second intervals. The first and second stimulations involved two identical 45 second exposures to either 25 or 50μM NMDA (separated by 10min), whilst the third stimulation was a 75mM KCl exposure (third stimulation data not shown). Vehicle/Buffer alone (control) or various treatments (tPA, ctPA, RAP, plasmin) were perfused for 5min over the cells in between the two transient NMDA exposures. A thorough example of this procedure has been published (Weiss et al. 2006). The data was analyzed using Leica physiology software with regions of interest (ROI) corresponding to the cell body being selected. Each ROI was assigned a N=1 value and only ROI that displayed a sharp, definitive rise in fluorescence from all three stimulations were analyzed. For each ROI, the Δ[Ca2+]i (i.e. area under the curve) above baseline (i.e. median value of the unstimulated periods) was measured and the second NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i was expressed relative to the first NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i. This value was averaged across all ROI within the same treatment group (i.e. % modulation). The % modulation for each “treated” group was normalized to that of the “control” group (i.e. % modulation relative to control). Each independently seeded culture was assigned an n=1 value. Differences between treatment groups were tested by one-way ANOVA and post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons with p<0.05 being considered as statistically significant. Note, none of the modulatory agents were found to discernibly alter basal calcium flux (suppl. Fig.S6).

Tissue protein extracts

Unless indicated, all buffers/manipulations were at 4°C. An adult mouse brain was removed and rinsed with PBS (0.137M NaCl, 2.68mM KCl, 10mM Na2HPO4, 1.76mM KH2PO4 pH 7.4). The cortices were dissected, rinsed again in PBS, then homogenized in RIPA buffer (50mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1% Na deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1mM PMSF, 5mg/L aprotinin, 5mg/L leupeptin, 2mM imidazole, 1mM NaF, 1mM Na3VO4). The homogenate was centrifuged (400×g, 5min) and the supernatant stored at −80°C. Protein extracts of the liver were prepared in the same manner.

Cell-free cleavage assay

An adult mouse brain was removed and washed with PBS. The cortices were dissected, rinsed again in PBS, then homogenized in PBS containing 2.5% Triton X-100. The resulting homogenate was pelleted by centrifugation (400×g, 5min), and the protein concentration of the supernatant quantified and adjusted to 3mg/ml. Proteases (plasmin, tPA, thrombin; 4-25μl) were added to 0.5ml aliquots of the cortical lysates and incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes to 2 hours. 50μg of each sample was then subjected to immunoblot.

Cell-based cleavage assay

DIV12 culture media (in 24-well plates) was replaced with phenol red-free and B27-free Minimum Essential Medium with Earle’s salts (400μl per well) and incubated for 1 hour in a humidified 37°C incubator. Proteases (tPA, plasmin, thrombin; 2-10μl) were added to the media and incubated for 10 min or 1 hour, after which the media was aspirated and RIPA buffer added to each well. The lysates were collected, quantified and stored at −80°C.

Immunoblot analyses

Samples were boiled in SDS-loading buffer with DTT, subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were probed with primary antibodies [mouse anti-NR1 N-terminal (Chemicon Int., 1:300-1000), goat anti-NR1 C-terminal (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., 1:100-1000), goat anti-tPA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., 1:1000), sheep anti-plasminogen (Serotec), rabbit anti-GFAP (DakoCytomation, 1:1000), mouse anti-GAPDH (Chemicon Int., 1:5000), 4B3 mouse monoclonal anti-rat PN-1 (Meier et al. 1989)] followed by appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody [sheep anti-mouse IgG (Chemicon Int., 1:5000), rabbit anti-goat IgG (Sigma, 1:5000), rabbit anti-sheep IgG (Chemicon Int., 1:5000)]. Signals were revealed by chemiluminescence (Supersignal, Thermo Scientific).

Electrophysiology

RNA preparation, oocyte preparation and expression of NMDAR subunits in Xenopus oocytes were performed as described previously (Kloda & Adams 2005). Plasmids with cDNA encoding the rat NR1a and NR2A NMDAR subunits were kindly provided by Dr. J. Boulter (UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA). All oocytes were injected with a 1:3 ratio of 5ng NR1a and 15ng NR2A cRNA, respectively and kept at 18°C in ND96 buffer (96mM NaCl, 2mM KCl, 1.8mM CaCl2, 1mM MgCl2 and 5mM HEPES pH 7.4) supplemented with 50mg/L gentamycin and 5mM pyruvic acid 2-5 days before recording. Membrane currents were recorded from Xenopus oocytes using a two electrode voltage virtual ground circuit on a Gene clamp 500B amplifier or an OpusXpress™ 6000A workstation, (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), as previously described (Clark et al. 2006). Electrodes were filled with 3M KCl and had resistances of 0.2-1.3Mohm. All recordings were conducted at 20-23°C using a Ca2+ and Mg2+-free solution (115mM NaCl, 2.5mM KCl, 1.8mM BaCl2 and 10mM HEPES at pH 7.3). Current amplitudes were determined by the steady-state plateau response elicited by 30μM glutamate and 10μM glycine, in the absence and presence of 1μM tPA and 250nM Plasmin at a holding potential of −70 mV. Membrane currents were sampled at 500Hz and filtered at 200Hz.

RESULTS

Potentiation of NMDA-induced [Ca2+]i is dependent upon proteolytic activity

tPA has previously been shown to potentiate NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i (Nicole et al. 2001, Reddrop et al. 2005, Park et al. 2008). To ascertain whether the ability of tPA to augment NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i was dependent on its proteolytic capacity, we utilized a novel inactive variant of tPA termed “ctPA” (PAION GmbH, Germany). Relative to tPA, ctPA retained <0.01% activity by amidolytic assay (data not shown), was 100-1000 fold less active by fibrin zymography (Fig.1A), and was equivalent in molecular weight (suppl. FigS1) and receptor binding (suppl. Table S2). As shown in Fig.1B-C, while 500nM tPA enhanced NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i, ctPA failed to elicit any potentiation. Rather, 500nM ctPA appeared to slightly suppress this calcium response. The basis of this suppression is unknown. Notably, 1μM ctPA also failed to augment NMDA-evoked Δ[Ca2+]i (data not shown). Thus, tPA potentiates NMDA-triggered Δ[Ca2+]i in a manner dependent on its proteolytic activity.

Plasmin, but not tPA, can cleave the NR1 subunit

The requirement for proteolytic capacity implies the existence of a tPA-sensitive substrate. Previous studies have identified the NR1 subunit of the NMDAR as the operative substrate in this setting (Nicole et al. 2001, Fernandez-Monreal et al. 2004a, Benchenane et al. 2007). To determine whether tPA can cleave NR1 we performed “cell-based” cleavage assays. In these assays, 500nM tPA was added to the media of neuronal cultures for 10 minutes. As a control, cultures were also treated with 250nM plasmin or 500nM thrombin – two other trypsin-like serine proteases. Cell lysates were then prepared and NR1 content assessed by immunoblot analysis. As shown in Fig.2A, only plasmin was able to cleave the NR1 subunit producing a 90kDa fragment. Incubation of cultures with the indicated proteases for 1 hour resulted in no additional effects (data not shown). This finding suggests that the plasmin-mediated cleavage of full-length NR1 to the 90kDa fragment utilizes portions of the NMDAR that are appropriately exposed on the cell-surface. To account for the possibility that cleavage of the NMDAR by tPA required NMDA engagement, similar cleavage experiments were also performed in the presence of NMDA. Under these conditions, tPA still failed to cleave NR1 (data not shown).

Our cell-based cleavage assays also show that plasmin treatment does not deplete full-length NR1. This finding reflects the fact that bath-applied proteases cannot access the full complement of cellular NMDARs (as a proportion of NMDARs exist intracellularly (Xia et al. 2001)). To circumvent this, we utilized a “cell-free” cleavage assay, whereby protein lysates of the adult tPA−/− mouse cortex were incubated with plasminogen, tPA, and aprotinin (a reversible plasmin inhibitor). To ensure that tPA was fully active, we also supplemented lysates with cyanogen-digested fibrinogen (CNBr-F); a co-factor that potently enhances tPA activity towards certain substrates (Schaefer et al. 2006, Verheijen et al. 1982). Lysates were then incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C and the NR1 content assessed by immunoblotting. To accommodate for the possibility that NR1 cleavage products contain epitopes that are not recognized by a single antibody, we used two different anti-NR1 antibodies – one directed against the extracellular N-terminal domain and one directed against the intracellular C-terminal domain of NR1 (Fig.2C). As shown in Fig.2B, immunoblotting with either anti-NR1 antibody revealed that whilst tPA or tPA+CNBr-F were unable to proteolyse NR1, co-incubation with tPA+plasminogen resulted in complete NR1 cleavage (see suppl. Fig.S2 for quantitation of Fig.2B). Aprotinin inhibited NR1 degradation caused by tPA+plasminogen incubation. As expected, under these cell-free conditions, a loss of full-length NR1 coincided with the appearance of three NR1 fragments: a ~120, 90 and 60kDa species. The 90kDa fragment is presumably the same as that detected in our cell-based assays, whilst the 60kDa is most likely a consequence of the cell-free conditions whereby regions of NR1 which are spatially hidden become available for ectopic proteolysis. Notably, aprotinin blocked the conversion of single-chain to two-chain tPA (a plasmin-dependent process), but did not inhibit conversion of plasminogen to plasmin (a tPA-dependent process). Thus, plasmin inhibition, rather than tPA inhibition, was responsible for the blockage of NR1 proteolysis by aprotinin. Fig.2B also shows that the anti-NR1 C-terminal antibody failed to detect any cleaved NR1 products. Interestingly, whilst immunoblotting with the anti-NR1 N-terminal antibody revealed that aprotinin potently inhibited plasmin-mediated NR1 degradation, immunoblotting with the anti-NR1 C-terminal antibody revealed only slight inhibition of NR1 degradation. This discrepancy suggests that NR1 has at least two plasmin-sensitive cleavage sites: one that is highly plasmin-sensitive (poorly inhibited by aprotinin) and another that is moderately plasmin-sensitive (effectively inhibited by aprotinin).

Our cleavage data best fits a model where a highly plasmin-sensitive cleavage site resides within the short intracellular C-terminal tail. Cleavage at this C-terminal site produces the 120kDa fragment. Removal of the intracellular C-terminal tail would explain why all cleavage fragments are not detected by the anti-NR1 C-terminal antibody (Fig.2C). Cleavage at two separate sites yields the 90 and 60kDa fragments

Given the results obtained from the cell-based cleavage assays, the 90kDa plasmin-generated fragment is the only species that can occur under physiological conditions. Fig.2C provides a schematic of how this 90kDa fragment can be generated from full length NR1 by plasmin.

To confirm the identity of the NR1 cleavage fragments, immunoprecipitations with the anti-NR1 C-terminal antibody were performed from neuronal culture lysates. The immunoprecipitated material was then plasmin-digested and subjected to anti-NR1 N-terminal immunoblot. The 120, 90 and 60kDa species appeared following plasmin-digestion (suppl. Fig.S3). Thus, plasmin can generate the appropriate NR1 cleavage fragments from immunoprecipitated full-length native NR1. Bioinformatic analysis highlights either Arg704-His705 or Lys316-Tyr317 as the putative plasmin-sensitive cleavage site responsible for the 90kDa fragment (Fig.2C).

Additional cell-free cleavage assays using wild-type mouse cortical lysates incubated with 1μM tPA, 250nM plasmin or 500nM thrombin for 10 minutes and 2 hours support our conclusion that plasmin, but not tPA, can cleave NR1 (data not shown). Thrombin, albeit with markedly lower efficiency, was also capable of producing the 90 and 60kDa NR1 fragments under cell-free conditions, suggesting utilization of the same cleavage sites (data not shown) (Gingrich et al. 2000).

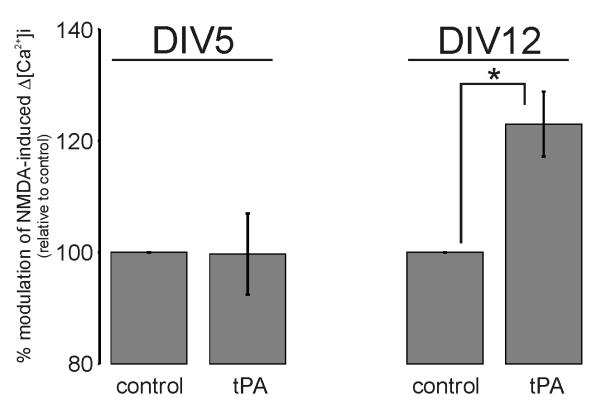

Potentiation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i is a function of culture age

NR1 is an obligatory subunit of the NMDAR. Therefore, if NMDAR potentiation involved a direct association between tPA and NR1, then tPA should impact on any neuron with functional cell-surface NMDARs. But, despite NMDA eliciting a classical Δ[Ca2+]i in both DIV5 and DIV12 cultures (suppl. Fig.S4), tPA only potentiated NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i in DIV12 cultures (Fig.3). Hence, the ability of tPA to modulate NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i is a function of in vitro culture age. That tPA cannot influence NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i in early (DIV5) cultures denotes a requirement for additional cellular factors besides tPA and the NMDAR.

Figure 3. tPA potentiation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i is a function of in vitro culture age.

Collated data demonstrating the potentiating effect of 500nM tPA on 50μM NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i only in mature DIV12 culture. Data represents mean ±SEM of the second NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i relative to the first NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i (i.e. % modulation). All data was normalized to control values. For DIV5 the data was pooled from N=161 cells (control) and N=153 cells (tPA) over four independent cultures (n=4). For DIV12 the data was pooled from N=36 cells (control) and N=56 cells (tPA) over three independent cultures (n=3; * p<0.05). Suppl. Fig.S4 shows the changes in the appearance, NMDA-responsiveness and NMDAR subunit expression that arose during in vitro culture maturation.

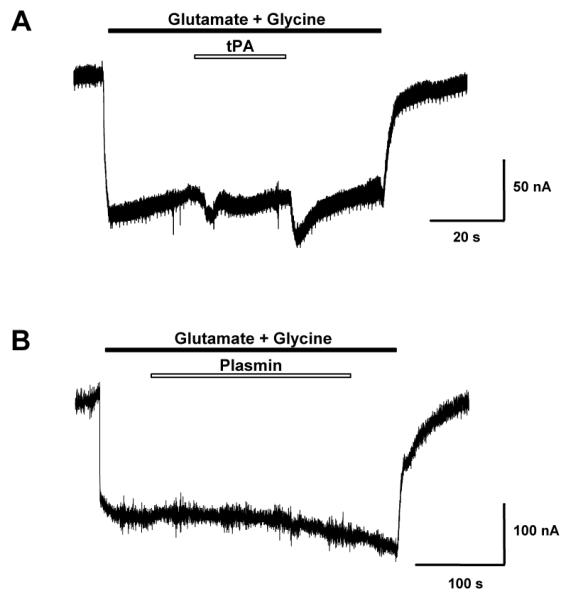

tPA alone does not alter NMDAR currents

To confirm that additional cellular factors were required for the potentiation of NMDAR function by tPA, we measured NMDAR-mediated currents in a heterologous non-neuronal system via two-electrode voltage clamp. Expression of heteromeric NR1a/2A NMDARs in Xenopus oocytes generated functional glutamate-activated channels, which were activated by 30μM glutamate and 10μM glycine. The addition of 1μM tPA for 30 seconds to the activated NMDAR revealed no change to the NMDAR-mediated current amplitude (101.3 ±2.5%; p>0.05 by t-test, n=17; Fig.4A). The addition of 250nM plasmin in the open state of the NMDAR also revealed no change to the NMDAR-mediated current (100.5 ±2.5 %; n=4; Fig.4B). As tPA was incapable of altering NMDAR-mediated current in this isolated non-neuronal system, we conclude that tPA requires additional cellular factors to potentiate NMDAR function. This finding, in conjunction with our evidence showing that NR1 is not a tPA-sensitive substrate, contradicts the postulate that tPA directly alters NMDAR function via NR1 cleavage (Nicole et al. 2001, Fernandez-Monreal et al. 2004a).

Figure 4. tPA does not alter recombinant NMDA-mediated currents in expressed heterologous Xenopus oocytes.

Shown is a representative trace of NR1a/2A NMDA-mediated currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Cells were voltage clamped at −70mV. NMDA-mediated currents were first evoked with 30μM glutamate and 10μM glycine (black bar), then during NMDAR activation either (A) 1μM tPA or (B) 250nM Plasmin (open white bars) were transiently co-applied. Artifact peaks in Panel A were due to solution exchange. For tPA, a total of 17 independent experiments were conducted. For plasmin, a total of 4 independent experiments were conducted.

Potentiation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i is plasmin-independent

Having gained strong evidence against NR1 being a tPA-sensitive substrate, we next considered the prototypical substrate for tPA; namely plasminogen. Consequently, we monitored the modulatory effect of 25nM plasmin on NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i. As shown in Fig.5, unlike tPA, the perfusion of 25nM plasmin resulted in no enhancement of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i. Therefore, we conclude that tPA potentiates NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i in a manner independent of plasmin(ogen). A concentration of 25nM plasmin was chosen on the basis that treatment of neuronal cultures with 25nM plasmin resulted in NR1 cleavage (data not shown), whereas treatment of cultures with tPA failed to result in NR1 cleavage (Fig.2A). Hence, the concentration of plasminogen in our cultures must be less than 25nM.

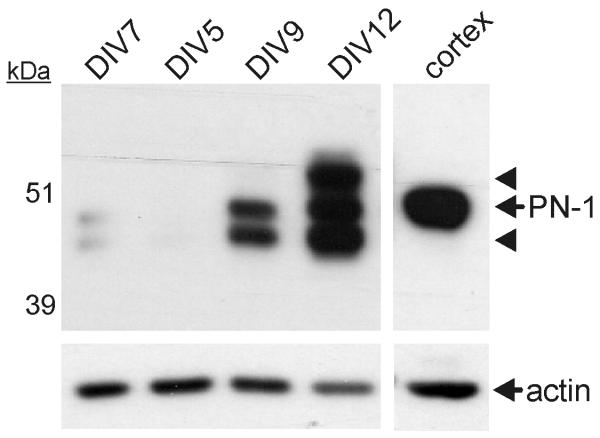

Expression of PN-1 correlates with culture maturity

Besides plasminogen, tPA also displays high proteolytic activity towards several serpins, notably PAI-1, neuroserpin and protease nexin-1 (PN-1) (Hastings et al. 1997, Rossignol et al. 2004, Lawrence et al. 1995). A prior study has shown that PN-1 and tPA together regulate NMDAR function (Kvajo et al. 2004). Consequently, we determined whether our neuronal cultures expressed PN-1. As shown in Fig.6, PN-1 was virtually absent from DIV5 cultures, but was abundant in DIV12 cultures. Whilst we cannot exclude the role of other tPA sensitive serpins, this strong correlation between PN-1 expression and the ability of tPA to enhance NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i led us to postulate that PN-1 may be an additional cellular factor required for the modulation of NMDAR function by tPA.

Figure 6. Protease Nexin-1 (PN-1) expression increases dramatically during in vitro culture maturation.

Cellular protein lysates were obtained from neuronal cultures at different days of in vitro (DIV) maturation. Lysates were collected and analyzed in quadruplicate from two independently-seeded cultures (n=2, N=8). PN-1 expression was assessed by immunoblot analysis. The membrane was re-probed for actin as a loading control. An adult mouse brain cortical lysate was used as a positive control for PN-1 (arrows). Arrowheads indicate probable alternate glycosylated forms of PN-1. Samples were loaded onto the gel in a blinded fashion in the order DIV 7, 5, 9 and 12 as indicated.

Potentiation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i by tPA requires LDLR engagement

PN-1 rapidly forms a complex with tPA, which in turn avidly binds to cell-surface LDLRs, initiating intracellular signaling cascades and tPA:serpin complex internalization (Herz & Strickland 2001). Indeed, LDLRs are the sole recognized receptor for tPA:serpin complexes. Accordingly, we assessed whether LDLR engagement was required for tPA to potentiate NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i. For this, we utilized the LDLR pan-ligand blocker, Receptor-Associated Protein (RAP). As shown in Fig.7, we observed that whilst the application of RAP alone produced no significant change in NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i, it fully ablated the ability of tPA to enhance NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i. This observation suggests that tPA-mediated potentiation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i is dependent upon LDLR engagement. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that potentiation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i involves tPA:serpin complex formation and subsequent LDLR engagement.

DISCUSSION

Several studies document that tPA potentiates NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i (Nicole et al. 2001, Reddrop et al. 2005, Park et al. 2008). The currently proposed mechanism involves direct cleavage of NR1 by tPA, which in turn increases the Ca2+-permeability of the NMDAR (Nicole et al. 2001). In support of a proteolytic event, the reversible tPA inhibitor, tPA-STOP, has been shown to diminish the influence of exogenous tPA on NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i (Liot et al. 2004). The low concentration of tPA-STOP (10nM) relative to exogenous tPA (~300nM), however, queries this interpretation. Consequently, our finding that an inactive tPA fails to enhance NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i conclusively demonstrates that the enhancement of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i relies upon the proteolytic capacity of tPA.

Implicit in the requirement for proteolytic activity is the existence of an effector substrate. Published evidence from one laboratory defines NR1 as the pertinent substrate (Fernandez-Monreal et al. 2004a, Benchenane et al. 2007). In an attempt to detect proteolysis of NR1, both cell-free and cell-based cleavage assays were performed. Cleavage times were varied from 10 min to 2 hours, and tPA concentrations from 50nM to 1μM were tested. Yet, despite trialing these different conditions, no evidence for the proteolysis of NR1 by tPA was found. Cell-based experiments in the presence of NMDA were also conducted and still no tPA-mediated NR1 proteolysis was observed (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that NR1 is not a tPA-sensitive substrate. This conclusion extends the findings of others (Liu et al. 2004, Matys & Strickland 2003, Kvajo et al. 2004).

If not NR1, then what is the operative tPA-sensitive substrate? Platelet-derived growth factor-C (PDGF-C) represented a logical candidate (Fredriksson et al. 2004, Boucher et al. 2003, Su et al. 2008). However, we found that PDGF-C expression remained unchanged during neuronal culture development (data not shown) and thus PDGF-C represents an unlikely effector of tPA-mediated NMDAR modulation.

Our data, in conjunction with published data (Nicole et al. 2001), also suggests that plasminogen is not the tPA-sensitive substrate in question. Our findings do however, indicate that LDLR engagement is vital for tPA to influence NMDAR function. A direct interaction between tPA and a LDLR could explain how RAP ablates the enhancement of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i by tPA. Several lines of evidence point against this possibility. First, our surface plasmon resonance experiments (suppl. Table S2), together with other studies (Hu et al. 2006, Orth et al. 1994, Zhuo et al. 2000, Martin et al. 2008), suggest that tPA cannot proteolyse LDLRs. Second, despite having differential effects on NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i, both ctPA and tPA bind to LDLRs with high nanomolar Kd (~330nM; suppl. Table S2). Thus, the potentiation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i is unlikely to be explained by the direct association/proteolysis of a LDLR by tPA. Lastly, none of the tested LDLR family members (LRP-1, LRP-1B, ApoER2, Megalin and VLDLR) exhibited differences in expression between DIV5 and DIV12 cultures (data not shown). On the other hand, tPA displays potent and specific proteolytic activity towards several serpins, with the resultant tPA:serpin complex strongly binding to numerous LDLRs with low nanomolar Kd (Horn et al. 1997, Makarova et al. 2003). Additionally, we have observed that PN-1 expression in our cultures increases dramatically from DIV5 to DIV12. Therefore, PN-1 likely represents the tPA-sensitive substrate responsible for the potentiation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i. We propose a model whereby tPA first complexes with PN-1 or another differentially expressed serpin, then binds to a LDLR and signals for an enhancement of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i. Both the requirement for tPA to be proteolytically active and the ability of RAP to block the influence of tPA on NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i are in keeping this model. It will be interesting to determine whether addition of PN-1 to DIV5 cultures restores the ability of tPA to potentiate NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i.

Further support for a tPA:PN-1 complex being a modulator of NMDAR function stems from the observation that both tPA−/− and PN-1−/− mice have reduced NR1 availability (D. Monard, unpublished data). Other tPA-reactive serpins may also elicit similar effects on NMDAR function. For example, it has been hypothesized that tPA, via complex formation with PAI-1, mediates NMDAR-dependent hyperemia (Park et al. 2008).

The links between tPA, LDLRs and the NMDAR are compelling. For instance, tPA facilitates NMDAR-dependent synaptic plasticity via engagement of the prototypical LDLR, LRP-1 (Zhuo et al. 2000). And similar to the influence of tPA described here-in, numerous LRP-1 ligands alter NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i (Qiu et al. 2002, Qiu et al. 2003). LRP-1 also physically associates with the NMDAR (May et al. 2004). Lastly, a recent study has demonstrated that tPA may elicit NMDAR activation in a LRP-1-dependent manner (Martin et al. 2008). Given these ties, it is noteworthy that NMDAR- and tPA-dependent LTP remains RAP-blockable despite the absence of neuronal LRP-1 (May et al. 2004). One possible explanation for this is that glial LRP-1 expression is critical for tPA to alter NMDAR function. Astrocytes are key mediators of neurotransmission that facilitate LTP (Yang et al. 2003). Furthermore, astrocytes are a significant component of our cultures (suppl. Fig.S5). Thus, we cannot exclude the involvement of astrocytes in our observations. In fact, a peri-cellular communication mechanism between neurons and astrocytes merits consideration, particularly as astrocytic uptake of tPA is blocked by RAP (Fernandez-Monreal et al. 2004b), as tPA triggers LRP-1 shedding from astrocytes (Polavarapu et al. 2007), and as astrocytes are known NMDAR modulators (Wolosker et al. 2002). Alternatively, it is possible that other LDLRs besides LRP-1 are central to the potentiation of NMDA-triggered events by tPA.

Distinct from the potentiation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i, our experiments reveal the novel ability of plasmin to discretely proteolyse NR1. We propose that plasmin can efficiently remove the very distal C-terminal portion of NR1. As a result, antibodies raised against the C-terminal portion of NR1 do not detect the ~120kDa N-terminal fragment of NR1 (or the subsequent 90 and 60kDa fragments). This model likely explains why previous cell-free experiments have shown that plasmin, instead of discretely cleaving NR1, can completely degrade NR1 (Matys & Strickland 2003). Notably, whilst no effect on rudimentary NMDAR-mediated ion conductance was observed (Fig.4), the impact of plasmin-mediated NR1 cleavage on other NMDAR properties such as allosteric modulation, cell-surface location and internalization rate remains unknown. That plasmin could efficiently proteolyse the extracellular domain of NR1 in the context of native cell-surface NMDARs intimates biological significance. Indeed, cleavage of NR1 by plasmin most likely occurs under chronic stress, a condition where plasmin has been shown to drastically decrease hippocampal NR1 levels (Pawlak et al. 2005b).

In conclusion, our investigations establish the plasmin-independent potentiation of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i by tPA. Even though tPA needs to be proteolytically active, we find no evidence that tPA can directly cleave the NR1 subunit. Furthermore, our data suggests that the enhancement of NMDA-induced Δ[Ca2+]i by tPA is mediated by a LDLR co-receptor. A similar set of experimental criteria has been previously described, whereby tPA increases blood-brain barrier permeability in a manner dependent upon proteolysis, independent of plasminogen and reliant upon LRP-1 (Yepes et al. 2003). As such, we hypothesize that tPA acts on a non-plasminogen substrate. Subsequent to this cleavage event, a LDLR is engaged, which in turn augments calcium flux downstream of the NMDAR. Given the dramatic increase in PN-1 between DIV5 and DIV12 cultures, PN-1 presents as the operative non-plasminogen substrate in this setting. This multi-factorial mechanism may underlie some of the proteolytic, yet plasmin-independent roles of tPA (Schaefer et al. 2007, Yepes et al. 2002, Yepes et al. 2003, Pawlak et al. 2002, Kumada et al. 2005, Park et al. 2008). Finally, adding to the ways in which the plasminogen activator system can modulate the NMDAR, our analyses uncover the capacity of plasmin to discretely cleave the NR1 subunit of the NMDAR.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by grants awarded to R.L.M. from the National Health and Medical Research Foundation of Australia. A.L.S. was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award and a Monash University Faculty of Medicine Postgraduate Excellence Award. We thank Prof. Karl-Uwe Petersen (PAION GmbH) for providing the ctPA and for advice and Prof. Dudley Strickland for providing anti-LRP-1 antibodies and RAP. The contribution of Assoc. Prof. Marie Ranson (University of Wollongong) is also acknowledged. BIAcore equipment was funded by Wellcome Trust Grant #052458. We thank Dr Warwick Nesbitt for his assistance with the confocal microscopy and calcium flux studies and Prof. David Adams for his support and laboratory facilities.

Abbreviations used

- NMDA

N-Methyl-D-Aspartate

- NMDAR

NMDA receptor

- tPA

tissue-type plasminogen activator

- kDa

kilodalton

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- LDLR

low-density lipoprotein receptor

- RAP

receptor-associated protein

- DIV

days in vitro

- LRP-1

low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1

- CNBr-F

cyanogen bromide-digested fibrinogen

- Δ[Ca2+]i

change in free intracellular calcium

REFERENCES

- Backes BJ, Harris JL, Leonetti F, Craik CS, Ellman JA. Synthesis of positional-scanning libraries of fluorogenic peptide substrates to define the extended substrate specificity of plasmin and thrombin. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:187–193. doi: 10.1038/72642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benchenane K, Castel H, Boulouard M, et al. Anti-NR1 N-terminal-domain vaccination unmasks the crucial action of tPA on NMDA-receptor-mediated toxicity and spatial memory. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:578–585. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher P, Gotthardt M, Li WP, Anderson RG, Herz J. LRP: role in vascular wall integrity and protection from atherosclerosis. Science. 2003;300:329–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1082095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RJ, Fischer H, Nevin ST, Adams DJ, Craik DJ. The synthesis, structural characterization, and receptor specificity of the alpha-conotoxin Vc1.1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23254–23263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604550200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Monreal M, Lopez-Atalaya JP, Benchenane K, et al. Arginine 260 of the amino-terminal domain of NR1 subunit is critical for tissue-type plasminogen activator-mediated enhancement of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004a;279:50850–50856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Monreal M, Lopez-Atalaya JP, Benchenane K, et al. Is tissue-type plasminogen activator a neuromodulator? Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004b;25:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson L, Li H, Fieber C, Li X, Eriksson U. Tissue plasminogen activator is a potent activator of PDGF-CC. Embo J. 2004;23:3793–3802. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich MB, Junge CE, Lyuboslavsky P, Traynelis SF. Potentiation of NMDA receptor function by the serine protease thrombin. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:4582–4595. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04582.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosalia DN, Salisbury CM, Maly DJ, Ellman JA, Diamond SL. Profiling serine protease substrate specificity with solution phase fluorogenic peptide microarrays. Proteomics. 2005;5:1292–1298. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granelli-Piperno A, Reich E. A study of proteases and protease-inhibitor complexes in biological fluids. J Exp Med. 1978;148:223–234. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.1.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JL, Backes BJ, Leonetti F, Mahrus S, Ellman JA, Craik CS. Rapid and general profiling of protease specificity by using combinatorial fluorogenic substrate libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7754–7759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140132697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings GA, Coleman TA, Haudenschild CC, Stefansson S, Smith EP, Barthlow R, Cherry S, Sandkvist M, Lawrence DA. Neuroserpin, a brain-associated inhibitor of tissue plasminogen activator is localized primarily in neurons. Implications for the regulation of motor learning and neuronal survival. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:33062–33067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz J, Strickland DK. LRP: a multifunctional scavenger and signaling receptor. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:779–784. doi: 10.1172/JCI13992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn IR, van den Berg BM, van der Meijden PZ, Pannekoek H, van Zonneveld AJ. Molecular analysis of ligand binding to the second cluster of complement-type repeats of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Evidence for an allosteric component in receptor-associated protein-mediated inhibition of ligand binding. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13608–13613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu K, Yang J, Tanaka S, Gonias SL, Mars WM, Liu Y. Tissue-type plasminogen activator acts as a cytokine that triggers intracellular signal transduction and induces matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2120–2127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins DJ, Grant GH. The function of the amino terminal domain in NMDA receptor modulation. J Mol Graph Model. 2005;23:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloda A, Adams DJ. Voltage-dependent inhibition of recombinant NMDA receptor-mediated currents by 5-hydroxytryptamine. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:323–330. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumada M, Niwa M, Hara A, Matsuno H, Mori H, Ueshima S, Matsuo O, Yamamoto T, Kozawa O. Tissue Type Plasminogen Activator Facilitates NMDA-Receptor-Mediated Retinal Apoptosis through an Independent Fibrinolytic Cascade. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1504–1507. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvajo M, Albrecht H, Meins M, Hengst U, Troncoso E, Lefort S, Kiss JZ, Petersen CC, Monard D. Regulation of brain proteolytic activity is necessary for the in vivo function of NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9734–9743. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3306-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence DA, Ginsburg D, Day DE, Berkenpas MB, Verhamme IM, Kvassman JO, Shore JD. Serpin-protease complexes are trapped as stable acyl-enzyme intermediates. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25309–25312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liot G, Benchenane K, Leveille F, et al. 2,7-Bis-(4-amidinobenzylidene)-cycloheptan-1-one dihydrochloride, tPA stop, prevents tPA-enhanced excitotoxicity both in vitro and in vivo. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:1153–1159. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000134476.93809.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Cheng T, Guo H, Fernandez JA, Griffin JH, Song X, Zlokovic BV. Tissue plasminogen activator neurovascular toxicity is controlled by activated protein C. Nat Med. 2004;10:1379–1383. doi: 10.1038/nm1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner JE, Honigman LS, Grant WF, Gessford SK, Hansen AB, Silverman MA, Scalettar BA. Activity-dependent release of tissue plasminogen activator from the dendritic spines of hippocampal neurons revealed by live-cell imaging. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:564–577. doi: 10.1002/neu.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova A, Mikhailenko I, Bugge TH, List K, Lawrence DA, Strickland DK. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein modulates protease activity in the brain by mediating the cellular internalization of both neuroserpin and neuroserpin-tissue-type plasminogen activator complexes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50250–50258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AM, Kuhlmann C, Trossbach S, et al. The functional role of the second NPXY motif of the LRP1 beta -chain in tPA-mediated activation of NMDA receptors. J Biol Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707607200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matys T, Strickland S. Tissue plasminogen activator and NMDA receptor cleavage. Nat Med. 2003;9:371–372. doi: 10.1038/nm0403-371. author reply 372-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May P, Rohlmann A, Bock HH, et al. Neuronal LRP1 functionally associates with postsynaptic proteins and is required for normal motor function in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8872–8883. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8872-8883.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina MG, Ledesma MD, Dominguez JE, Medina M, Zafra D, Alameda F, Dotti CG, Navarro P. Tissue plasminogen activator mediates amyloid-induced neurotoxicity via Erk1/2 activation. Embo J. 2005 doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier R, Spreyer P, Ortmann R, Harel A, Monard D. Induction of glia-derived nexin after lesion of a peripheral nerve. Nature. 1989;342:548–550. doi: 10.1038/342548a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchor JP, Strickland S. Tissue plasminogen activator in central nervous system physiology and pathology. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:655–660. doi: 10.1160/TH04-12-0838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicole O, Docagne F, Ali C, Margaill I, Carmeliet P, MacKenzie ET, Vivien D, Buisson A. The proteolytic activity of tissue-plasminogen activator enhances NMDA receptor-mediated signaling. Nature Medicine. 2001;7:59–64. doi: 10.1038/83358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NINDS Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris EH, Strickland S. Modulation of NR2B-regulated contextual fear in the hippocampus by the tissue plasminogen activator system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13473–13478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705848104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth K, Willnow T, Herz J, Gething MJ, Sambrook J. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein is necessary for the internalization of both tissue-type plasminogen activator-inhibitor complexes and free tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21117–21122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park L, Gallo EF, Anrather J, Wang G, Norris EH, Paul J, Strickland S, Iadecola C. Key role of tissue plasminogen activator in neurovascular coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1073–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708823105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak R, Melchor JP, Matys T, Skrzypiec AE, Strickland S. Ethanol-withdrawal seizures are controlled by tissue plasminogen activator via modulation of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005a;102:443–448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406454102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak R, Nagai N, Urano T, Napiorkowska-Pawlak D, Ihara H, Takada Y, Collen D, Takada A. Rapid, specific and active site-catalyzed effect of tissue-plasminogen activator on hippocampus-dependent learning in mice. Neuroscience. 2002;113:995–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak R, Rao BS, Melchor JP, Chattarji S, McEwen B, Strickland S. Tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen mediate stress-induced decline of neuronal and cognitive functions in the mouse hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005b;102:18201–18206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509232102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polavarapu R, Gongora MC, Yi H, Ranganthan S, Lawrence DA, Strickland D, Yepes M. Tissue-type plasminogen activator-mediated shedding of astrocytic low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein increases the permeability of the neurovascular unit. Blood. 2007;109:3270–3278. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-043125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z, Crutcher KA, Hyman BT, Rebeck GW. ApoE isoforms affect neuronal N-methyl-D-aspartate calcium responses and toxicity via receptor-mediated processes. Neuroscience. 2003;122:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z, Strickland DK, Hyman BT, Rebeck GW. alpha 2-Macroglobulin exposure reduces calcium responses to N-methyl-D-aspartate via low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14458–14466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddrop C, Moldrich RX, Beart PM, Farso M, Liberatore GT, Howells DW, Petersen KU, Schleuning WD, Medcalf RL. Vampire bat salivary plasminogen activator (desmoteplase) inhibits tissue-type plasminogen activator-induced potentiation of excitotoxic injury. Stroke. 2005;36:1241–1246. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000166050.84056.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol P, Ho-Tin-Noe B, Vranckx R, Bouton MC, Meilhac O, Lijnen HR, Guillin MC, Michel JB, Angles-Cano E. Protease nexin-1 inhibits plasminogen activation-induced apoptosis of adherent cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10346–10356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson AL, Medcalf RL. Tissue-type plasminogen activator: a multifaceted modulator of neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2006;50:673–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer U, Machida T, Vorlova S, Strickland S, Levi R. The plasminogen activator system modulates sympathetic nerve function. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2191–2200. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer U, Vorlova S, Machida T, Melchor JP, Strickland S, Levi R. Modulation of sympathetic activity by tissue plasminogen activator is independent of plasminogen and urokinase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:265–273. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su EJ, Fredriksson L, Geyer M, et al. Activation of PDGF-CC by tissue plasminogen activator impairs blood-brain barrier integrity during ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2008;14:731–737. doi: 10.1038/nm1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheijen JH, Mullaart E, Chang GT, Kluft C, Wijngaards G. A simple, sensitive spectrophotometric assay for extrinsic (tissue-type) plasminogen activator applicable to measurements in plasma. Thromb Haemost. 1982;48:266–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent VA, Lowik CW, Verheijen JH, de Bart AC, Tilders FJ, Van Dam AM. Role of astrocyte-derived tissue-type plasminogen activator in the regulation of endotoxin-stimulated nitric oxide production by microglial cells. Glia. 1998;22:130–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YF, Tsirka SE, Strickland S, Stieg PE, Soriano SG, Lipton SA. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) increases neuronal damage after focal cerebral ischemia in wild-type and tPA-deficient mice. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:228–231. doi: 10.1038/nm0298-228. [see comments.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss TW, Samson AL, Niego B, Daniel PB, Medcalf RL. Oncostatin M is a neuroprotective cytokine that inhibits excitotoxic injury in vitro and in vivo. Faseb J. 2006;20:2369–2371. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5850fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolosker H, Panizzutti R, De Miranda J. Neurobiology through the looking-glass: D-serine as a new glial-derived transmitter. Neurochem Int. 2002;41:327–332. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H, Hornby ZD, Malenka RC. An ER retention signal explains differences in surface expression of NMDA and AMPA receptor subunits. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:714–723. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue F, Seto CT. Selective inhibitors of the serine protease plasmin: probing the S3 and S3′ subsites using a combinatorial library. J Med Chem. 2005;48:6908–6917. doi: 10.1021/jm050488k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Ge W, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Shen W, Wu C, Poo M, Duan S. Contribution of astrocytes to hippocampal long-term potentiation through release of D-serine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15194–15199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2431073100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yepes M, Sandkvist M, Coleman TA, Moore E, Wu JY, Mitola D, Bugge TH, Lawrence DA. Regulation of seizure spreading by neuroserpin and tissue-type plasminogen activator is plasminogen-independent. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;109:1571–1578. doi: 10.1172/JCI14308. [see comments.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yepes M, Sandkvist M, Moore EG, Bugge TH, Strickland DK, Lawrence DA. Tissue-type plasminogen activator induces opening of the blood-brain barrier via the LDL receptor-related protein. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1533–1540. doi: 10.1172/JCI19212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo M, Holtzman DM, Li Y, Osaka H, DeMaro J, Jacquin M, Bu G. Role of tissue plasminogen activator receptor LRP in hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:542–549. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00542.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.