Abstract

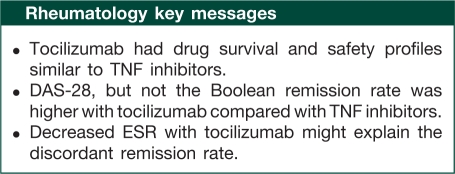

Objective. To assess the effectiveness, drug survival and safety of tocilizumab compared with TNF-α inhibitors in clinical practice.

Methods. Patients in the Cohort of Arthritis Biologic Users at Kameda Institute (CABUKI) registry who were on biologics during July 2003 to October 2010 were included. Remission rates at 6 months, Kaplan–Meier drug survival estimates and serious adverse event (SAE) rates were compared.

Results. A total of 247 RA patients were analysed. For first-line biologic users, the 6-month 28-joint DAS (DAS-28)-ESR remission rates were 66.7% for tocilizumab vs 25.8% for TNF inhibitors (P < 0.001, Fisher's exact test). This advantage disappeared with the application of the newly suggested Boolean remission criterion for clinical trials: 0% for tocilizumab vs 8.2% for TNF inhibitors (P = 0.367, Fisher's exact test). Tocilizumab users in DAS-28-ESR remission had lower mean ESR (3.9 mm/h for tocilizumab vs 7.9 mm/h for TNF inhibitors, P = 0.026, t-test) and higher mean swollen joint count (2.6 for tocilizumab vs 1.3 for TNF inhibitors, P = 0.036, t-test), thus failing to meet the more stringent Boolean criteria. First- and second-line tocilizumab users showed similar drug survival and SAE rates compared with TNF inhibitor users.

Conclusion. Tocilizumab had drug survival and safety profiles similar to those of TNF inhibitors in this Japanese single-centre registry. Tocilizumab was superior to TNF inhibitors when compared at 6 months by DAS-28-ESR remission. However, the newly suggested Boolean criteria are more appropriate measures of effectiveness as DAS-28-ESR remission by tocilizumab was mainly due to very low ESR in our study population.

Keywords: Tocilizumab, TNF inhibitors, Rheumatoid arthritis, Benefit, Safety, Treatment outcome, DAS-28, Boolean remission criteria

Introduction

RA is a multisystem inflammatory disorder, characterized by severe synovial involvement, the treatment of which has advanced substantially in the past two decades. Use of TNF inhibitors, such as infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab, results in remission in certain patients in clinical practice [1]. Given their effectiveness, TNF inhibitor use has become part of formal treatment recommendations [2, 3]. Despite this, a considerable number of patients fail to go into remission on TNF inhibitors, and require other treatments.

Tocilizumab is a humanized mAb against the IL-6 receptor, blocking its activity through competitive receptor binding [4]. Tocilizumab monotherapy was compared with MTX in the Study of Active controlled TOcilizumab monotherapy for Rheumatoid arthritis patients with an Inadequate response to methotrexate (SATORI) trial [5] in Japanese patients refractory to MTX therapy, and showed effectiveness in disease activity suppression. Recently, a systematic review by Singh et al. [6] concluded that tocilizumab was effective based on the eight clinical trials reviewed.

Attempts to compare different biologic agents both directly and indirectly have gained popularity in rheumatology. For example, Hetland et al. [1] reported a direct comparison of three TNF inhibitors using a nationwide registry in Denmark, finding that etanercept had the best drug survival rates, while adalimumab showed the best treatment response. Tocilizumab was not included in the study. Bergman et al. [7] compared tocilizumab's ACR response with that of other biologic agents indirectly via a systematic literature review. They concluded that tocilizumab had similar ACR 20 and ACR 50 response rates, but a higher ACR 70 response rate. In a more recent meta-analysis by Salliot et al. [8], clinical trials of biologic agents used in TNF inhibitor-refractory cases were reviewed. Tocilizumab as well as rituximab, abatacept and golimumab were found to be equally effective. However, data on comparison of biologic agents in a routine practice setting are scarce to date.

Clinical experience with tocilizumab has accumulated in Japan, where it was developed and first approved. In this Japanese single-centre, registry-based observational study, we report on the effectiveness, drug survival and safety of tocilizumab in comparison with TNF inhibitors.

Materials and methods

The present study was conducted at Kameda Medical Center, a community-based teaching hospital in a rural area of Japan. Approval of the ethics committee of the hospital was obtained (Institutional Review Board of Kameda Medical Center). Individual patient informed consent was not required under Japanese law, as the present study was purely observational.

The Cohort of Arthritis Biologic Users at Kameda Institute registry

We enrolled RA patients who started biologic treatment under our care into the Cohort of Arthritis Biologic Users at Kameda Institute (CABUKI) registry. This comprehensive database contains information on baseline characteristics of patients and disease activity at initial and follow-up visits. Serious adverse events (SAEs), defined as hospitalization or the need for i.v. antibiotics, were also recorded. The treating rheumatologist was responsible for data entry. Data were collected from the initiation of the biologic therapy to the discontinuation of the agent for any reason for >3 months.

Eligibility criteria

Patients who were clinically diagnosed with RA and treated with biologics between July 2003 and October 2010 were potentially eligible. Patients were excluded if the agent of choice was abatacept, as its use in Japan began towards the end of the inclusion period. Patients were also excluded if their biologics had been commenced at other institutions. Patients were grouped into first-, second- and third-line biologic groups. The first-line group was comprised of patients who were biologic naïve. Patients in the second- and third-line groups had used one or two previous biologic agents, respectively.

Effectiveness measures

Effectiveness was compared between the tocilizumab group and TNF inhibitors-combined group, which comprised infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab users, at 6 months by four remission criteria: DAS-28-ESR < 2.6, DAS-28-CRP < 2.3 and the Boolean remission criteria for both clinical practice and trials. The same comparison was done between first- and second-line tocilizumab and TNF inhibitor users. As DAS-28-CRP tends to be lower than DAS-28-ESR, we utilized the cut-off of 2.3 as suggested by Inoue et al. [9]. The Boolean criteria for clinical trials and practice were announced at the ACR annual meeting 2010 and recently published [10, 11]. Remission criteria for clinical trials are defined as tender joint count (TJC) ≤ 1, swollen joint count (SJC) ≤ 1, patient's global assessment (PGA) ≤ 1 out of 10 and CRP ≤ 1 mg/dl. Boolean criteria without CRP may be used in clinical practice until better measures become available. For patients with follow-up duration <6 months, the 6-month data were supplied using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method. Since prominent discrepancy exists between DAS-28-ESR and Boolean remission criteria, particularly in the first-line tocilizumab group, we performed additional comparisons of patients in DAS-28-ESR remission between the first-line tocilizumab group and the TNF inhibitors-combined group.

Statistical analyses

Continuous and categorical baseline variables were analysed using t-test and Fisher's exact test, respectively. Of these baseline variables, ones with univariate P < 0.2 or with clinical significance (tocilizumab use, male sex, age >65 years, current smoking status, RA disease duration, prednisolone use, MTX use, previous exposure to other biologics and DAS-28-ESR without PGA) were included in the models for multivariate analyses for remission, drug survival and SAE rate. Baseline DAS-28-ESR without PGA [DAS-28-ESR (three variables)] was used for multivariate analyses, as PGA was missing in 42 patients [12].

Baseline predictors of DAS-28-ESR and Boolean remission for clinical trials and practice at 6 months were determined with logistic regression models. Explanatory variables included in the Boolean remission prediction models were tocilizumab use, sex, age >65 years, current smoking status, RA disease duration, prednisolone use, MTX use, previous exposure to other biologics and DAS-28-ESR (three variables) at baseline. DAS-28-ESR remission prediction models were adjusted for these variables plus baseline lung disease and diabetes. Longitudinal changes in DAS-28-ESR were compared between the tocilizumab group and TNF inhibitors-combined group with linear mixed models including prednisolone dose and MTX dose as random effects.

Kaplan–Meier drug survival estimates of tocilizumab and TNF inhibitors-combined groups were analysed with a log-rank test. Baseline predictors of poor drug survival were determined using multivariable-adjusted Cox regression models adjusted for tocilizumab use, sex, age >65 years, BMI, current smoking status, RA disease duration, RF/ACPA positivity, lung disease, diabetes, concomitant autoimmune diseases, prednisolone use, MTX use, NSAID use, previous exposure to biologic agents and baseline DAS-28-ESR (three variables).

We also examined the rates of SAEs per 100 person-years (PY) of drug usage. Analysis by t-test compared the mean SAE rate (SAE/100 PY of drug usage) for each group. Baseline characteristics associated with SAE were analysed with linear regression models with the SAE rate as the response variable. Adjustment was done for baseline variables included in the Cox regression models, with the exception of BMI.

All statistical analyses were performed with R version 2.12 (http://www.r-project.org), except for linear mixed models, for which PASW Statistics version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used. All tests were two-sided when applicable. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

We identified 255 potentially eligible RA patients who were or had been on biologics. One patient on abatacept and seven patients whose biologic agents had been started at other hospitals were excluded, leaving 247 patients meeting inclusion criteria for the safety and drug survival analyses. There were 192 first-, 44 second- and 11 third-line biologic users. Seventeen patients without 6-month response data were excluded from the effectiveness analyses (n = 17, first-line infliximab 7, first-line etanercept 8, second-line etanercept 1 and second-line tocilizumab 1). Baseline characteristics of the overall cohort and first-line biologic users are shown in Table 1. Mean follow-up duration, mean MTX dose, prior history of malignancy and MTX use showed significant differences between the first-line biologic groups, whereas mean follow-up duration [tocilizumab group 10.3 (8.7) months vs TNF inhibitors-combined group 18.9 (13.2) months, P = 0.015] and mean age [tocilizumab group 62.9 (10.8) years vs TNF inhibitors-combined group 53.2 (16.7) years, P = 0.030] differed significantly in second-line tocilizumab (n = 22) and TNF inhibitor users (n = 22, infliximab 3, etanercept 17 and adalimumab 2). Characteristics of third-line biologic users did not differ between the tocilizumab (n = 7) and TNF inhibitors-combined group (n = 4, infliximab 1 and etanercept 3).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for the overall cohort and first-line biologic users

| Overall cohort (n = 247) |

First-line users (n = 192) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | TCZ (n = 47) | TNFi (n = 200) | TCZ (n = 18) | TNFi (n = 174) | ||

| Continuous variables, mean (s.d.) | P, t-test | P, t-test | ||||

| Follow-up duration, months | 9.6 (7.4) | 16.8 (15.6) | <0.001* | 9.4 (6.6) | 16.6 (16) | 0.001* |

| Age, year | 60.3 (11.4) | 57.7 (14.3) | 0.179 | 60.6 (8.9) | 58.1 (14) | 0.303 |

| BMIa | 23.9 (4.2) | 22.9 (3.8) | 0.133 | 22.6 (4.0) | 22.8 (3.7) | 0.889 |

| RA disease duration, year | 8.8 (7.3) | 8.1 (9.2) | 0.640 | 9.1 (8.6) | 7.9 (9.4) | 0.616 |

| Prednisolone dose, mg | 7.3 (4.3) | 7.0 (4.4) | 0.684 | 7.0 (5.7) | 6.8 (4.5) | 0.876 |

| MTX dose, mg/week | 6.9 (4.7) | 7.0 (3.8) | 0.894 | 4.3 (4.0) | 6.9 (3.6) | 0.015* |

| DAS-28-ESR (three variables) | 4.8 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.2) | 0.552 | 4.9 (1.2) | 5.0 (1.2) | 0.781 |

| DAS-28-ESR (four variables)b | 5.0 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.3) | 0.503 | 5.0 (1.3) | 5.2 (1.3) | 0.660 |

| Categorical variables, % | P, Fisher's exact test | P, Fisher's exact test | ||||

| Male | 19.1 | 25.0 | 0.452 | 22.2 | 25.9 | 1.000 |

| Elderly (age >65 year) | 36.2 | 34.5 | 0.866 | 38.9 | 33.9 | 0.795 |

| Current smokerc | 17.4 | 16.7 | 1.000 | 11.1 | 16.7 | 1.000 |

| RF/ACPA positivity | 89.4 | 89.0 | 1.000 | 94.4 | 88.5 | 0.699 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12.8 | 7.5 | 0.250 | 11.1 | 7.5 | 0.637 |

| Lung disease | 25.5 | 27.0 | 1.000 | 27.8 | 25.9 | 0.786 |

| Heart disease | 4.3 | 3.5 | 0.682 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 21.3 | 19.5 | 0.839 | 11.1 | 19.5 | 0.534 |

| Isoniazid prophylaxis | 63.8 | 69.0 | 0.492 | 61.1 | 70.7 | 0.424 |

| Concomitant autoimmune disease | 21.3 | 15.5 | 0.383 | 27.8 | 14.9 | 0.178 |

| FM | 6.4 | 6.5 | 1.000 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 0.604 |

| Prior history of malignancy | 10.6 | 3.5 | 0.056 | 22.2 | 3.4 | 0.008* |

| Prednisolone use | 91.5 | 91.0 | 1.000 | 83.3 | 89.7 | 0.424 |

| MTX use | 74.5 | 85.0 | 0.089 | 55.6 | 85.6 | 0.004* |

| NSAIDs use | 44.7 | 56.0 | 0.194 | 61.1 | 56.9 | 0.806 |

aNot available in eight patients. bNot available in 42 patients. cNot available in 21 patients. *Statistically significant. TCZ: tocilizumab; TNFi: TNF inhibitors.

Effectiveness comparison

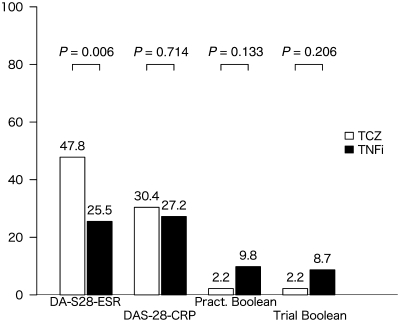

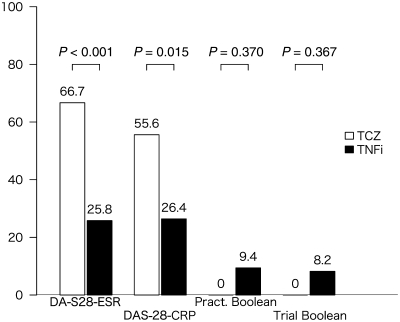

Comparisons of remission rates at 6 months are shown in Fig. 1 (n = 230: tocilizumab 46, infliximab 92, etanercept 87 and adalimumab 5), demonstrating a statistically significant difference by DAS-28-ESR remission criteria only. For first-line biologic users (n = 177: tocilizumab 18, infliximab 88, etanercept 68 and adalimumab 3), remission rates are shown in Fig. 2. Statistically significant differences existed in remission rates between the tocilizumab group and TNF inhibitors-combined group with regards to DAS-28-ESR and DAS-28-CRP remission criteria, but not with Boolean criteria. In the additional analysis, tocilizumab users in DAS-28-ESR remission had a significantly higher SJC and lower ESR compared with TNF inhibitor users in DAS-28-ESR remission (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Remission rates (%) by criteria for toclizumab vs TNF inhibitor groups (overall cohort). Pract Boolean: Boolean remission criterion for clinical practice; Trial Boolean: Boolean remission criterion for clinical trials; TCZ: tocilizumab; TNFi: TNF inhibitors.

Fig. 2.

Remission rates (%) by criteria for toclizumab vs TNF inhibitor groups (first-line users). Pract Boolean: Boolean remission criterion for clinical practice; Trial Boolean: Boolean remission criterion for clinical trials; TCZ: tocilizumab; TNFi: TNF inhibitors.

Table 2.

Comparison of mean values between first-line tocilizumab and TNF inhibitor users in DAS-28-ESR remission

| DAS-28-ESR components | TCZ | TNFi | P, t-test |

|---|---|---|---|

| TJC (0–28) | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.139 |

| SJC (0–28) | 2.6 | 1.3 | 0.036* |

| PGA (0–10) | 17.3 | 14.6 | 0.531 |

| ESR, mm/h | 3.9 | 7.9 | 0.026* |

*Statistically significant. TCZ: tocilizumab; TNFi: TNF inhibitors.

For second-line biologic users (n = 42: tocilizumab 21, infliximab 3, etanercept 16 and adalimumab 2), remission rates were 33.3, 14.3, 0 and 0% in the tocilizumab group, and 28.6, 38.1, 14.3 and 14.3% in the TNF inhibitors-combined group by DAS-28-ESR, DAS-28-CRP, Boolean criteria for clinical practice and Boolean criteria for clinical trials, respectively. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups regardless of the criteria used.

Remission predictors

Male sex was associated with a better chance of remission by the Boolean criteria for clinical trials [P = 0.004; odds ratio (OR) = 6.96, 95% CI 1.91, 28.11] and clinical practice (P = 0.011; OR = 4.70, 95% CI 1.42, 16.16). Using TNF inhibitors-combined as the reference, tocilizumab use was not a negative predictor by either of the Boolean criteria. Predictors of DAS-28-ESR remission at 6 months were tocilizumab use (P < 0.001, OR = 4.79, 95% CI 1.95, 12.52), male sex (P = 0.009, OR = 3.04, 95% CI 1.33, 7.17), age >65 years (P = 0.008, OR = 0.29, 95% CI 0.11, 0.70) and baseline DAS-28-ESR (three variables) (P < 0.001, OR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.36, 0.74).

In longitudinal analyses of DAS-28-ESR changes with linear mixed models, first-line tocilizumab users had significantly lower DAS-28-ESR (−1.25/12 months of drug usage, P = 0.011) compared with first-line TNF inhibitor users. The same held true for second-line tocilizumab users (−1.26/12 months, P < 0.001).

Drug survival and safety

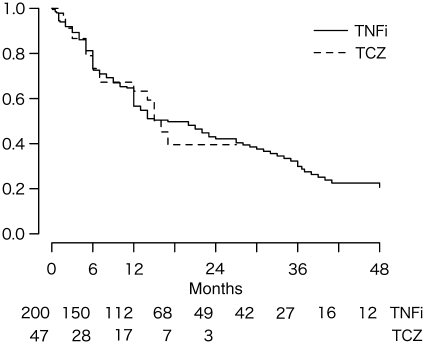

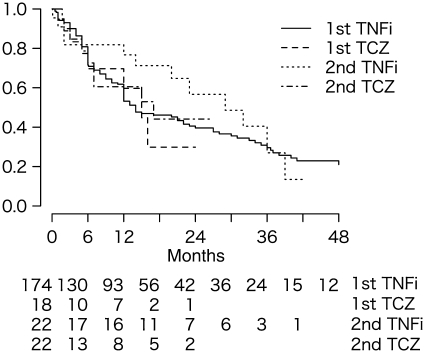

No significant difference was found in drug survival time as shown in Fig. 3 (P = 0.879, log-rank test) between the tocilizumab group and TNF inhibitors-combined group (n = 247, tocilizumab 47, infliximab 99, etanercept 96 and adalimumab 5). Between the first-line tocilizumab group and TNF inhibitors-combined group (n = 192, tocilizumab 18, infliximab 95, etanercept 76 and adalimumab 3), there was also no statistically significant difference (Fig. 4, P = 0.860, log-rank test). At 6 and 12 months, respectively, 69.6 and 59.7% remained on first-line tocilizumab, whereas 71.5 and 53.2% remained on TNF inhibitors. Reasons for drug discontinuation in each group were similar. Drug survival was also comparable (P = 0.354, log-rank test) between the second-line tocilizumab group (n = 22; 72.6% at 6 months, 60.5% at 12 months) and TNF inhibitors-combined group (n = 22; 81.8% at 6 months, 76.7% at 12 months), with similar reasons for discontinuation. Baseline factors associated with an increased risk of drug discontinuation were BMI [P = 0.013, hazard ratio (HR) = 1.06 for each 1-point increase in BMI, 95% CI 1.01, 1.11]. In contrast, previous exposure to other biologics (P = 0.016, HR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.31, 0.88), concomitant autoimmune disease (P = 0.042, HR = 0.56, 95% CI 0.32, 0.98) and NSAID use (P = 0.005, HR = 0.57, 95% CI 0.38, 0.84) were associated with decreased risk. Compared with TNF inhibitors-combined, tocilizumab use was not associated with changes in risk (P = 0.357, HR = 1.30, 95% CI 0.74, 2.27).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier drug survival estimates for all biologic users. Number at risk in each group is shown at the bottom. TCZ: tocilizumab; TNFi: TNF inhibitors.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier drug survival estimates for first- and second-line biologic users. Number at risk in each group is shown at the bottom. TCZ: tocilizumab; TNFi: TNF inhibitors.

Differences in mean SAE rate for each group were not statistically significant: 43.1/100 PY of drug usage for the tocilizumab group and 35.2/100 PY of drug usage for the TNF inhibitors-combined group (P = 0.730, t-test). When calculated by dividing the total number of SAEs by the total duration of drug usage, the SAE rates were 15.9/100 PY for the tocilizumab group and 13.9/100 PY for the TNF inhibitors-combined group. No baseline characteristics were associated with a significant increase in SAE rate. RF/ACPA positivity [P = 0.084, regression coefficient (RC) = −54.6/100 PY, 95% CI −116.6, 7.4], concomitant autoimmune disease (P = 0.099, RC = −46.6/100 PY, 95% CI −102.0, 8.8) and NSAIDs use (P = 0.062, RC = −3.1/100 PY, 95% CI −80.0, 1.9) were associated with a non-significant trend towards decreased risk of SAEs. Tocilizumab use (TNF inhibitors-combined as the reference) was not a significant predictor (P = 0.685, RC = +11.1/100 PY, 95% CI −42.7, 64.9).

The most common SAEs in the TNF inhibitors-combined group were pneumonia (14 events) followed by urinary tract infection (UTI) (4 events), worsening of interstitial lung diseases (3 events), malignancy (3 events) and pulmonary haemorrhage (3 events), whereas soft-tissue infections (2 events), UTI (2 events) and vasculitis (2 events) occurred in the tocilizumab group. One event of vasculitis and two events of soft-tissue infections also occurred in the TNF inhibitors-combined group.

Discussion

The present study assessed the effectiveness, drug survival and safety of tocilizumab in clinical practice compared with TNF inhibitors. In the effectiveness analysis, we found that first-line tocilizumab achieved higher remission rates than first-line TNF inhibitor use by both DAS-28-ESR and DAS-28-CRP remission criteria, but not by the new Boolean remission criteria. In the drug survival analysis, tocilizumab was comparable with TNF inhibitors both in first- and second-line use. In the safety analysis, SAE rates were similar between the tocilizumab and the TNF inhibitors-combined groups.

Tocilizumab achieved a higher 6-month remission rate than TNF inhibitors by DAS-28-ESR remission criterion. Tocilizumab users also achieved lower DAS-28-ESR values in the longitudinal analysis. Interestingly, none of the first-line tocilizumab users in DAS-28-ESR remission met the Boolean remission criteria. In fact, more patients in the TNF inhibitor groups were in remission by these new criteria, although the difference was not statistically significant.

Lower ESRs in first-line tocilizumab users in DAS-28-ESR remission caused this intriguing discrepancy. ESR was lower by 4 mm/h in this group (3.9 mm/h) compared with first-line TNF inhibitor users (7.9 mm/h) in DAS-28-ESR remission. ESR is heavily weighted in DAS-28-ESR [13]. More importantly, its weight rapidly decreases as ESR approaches zero, which commonly occurs in tocilizumab users. Thus a 4 mm/h decrease in ESR in this range causes DAS-28-ESR to decrease by approximately −0.49, effectively allowing patients to have an additional two to three swollen joints and still remain in remission by DAS-28-ESR criteria. As the Boolean remission criteria require the SJC to be ≤1, these first-line tocilizumab users in DAS-28-ESR remission failed to meet Boolean criteria.

Several groups have reported similar results comparing DAS-28-ESR remission with remission defined by the simple disease activity index (SDAI) and the clinical disease activity index (CDAI) [14, 15] in clinical trials. Nishimoto et al. [16] reported good correlation between DAS-28-ESR and SDAI/CDAI in the SATORI study, although remission rates at Week 24 by DAS-28-ESR (47.2%) and SDAI/CDAI (17.0 and 15.1%, respectively) showed differences. Smolen et al. [17] reported that tocilizumab achieved four times more DAS-28-ESR remission compared with CDAI remission, whereas TNF inhibitors achieved two times more DAS-28-ESR remission. They stated that although this discordance was most prominent with tocilizumab, it also happened with TNF inhibitors and MTX. We confirmed the new Boolean remission criteria are as stringent as SDAI/CDAI remission criteria. The problematic laxity of the DAS-28-ESR remission criterion, which affects all biologics, but appears to favour tocilizumab, may be avoided with the use of these new criteria.

The present study also confirmed that the drug survival of tocilizumab was comparable with the TNF inhibitors, both in first- and second-line use. The drug survival rate of tocilizumab was 69.6% at 6 months in first-line users, whereas 72.6% remained on tocilizumab at 6 months in the second-line group. This is similar to values reported in the REtrospective ACTemra Investigation for Optimal Needs of RA Patients (REACTION) study [18], in which 6-month drug survival rates of 78.5% for first-line users and 77.6% for the TNF inhibitor failure group were observed.

No pneumonia was observed in the tocilizumab group during the study period, whereas the number of serious soft-tissue infections was similar between these groups, even though the tocilizumab group had fewer patients and a shorter follow-up duration. This might suggest that infections associated with tocilizumab use are different from those associated with TNF inhibitor use. On the other hand, Campbell et al. [19] reported that most common infections occurring with tocilizumab use were skin and subcutaneous infections and respiratory tract infections, and similar infection profiles were observed in TNF inhibitor users. Japanese post-marketing surveillance yielded similar results; respiratory tract infections were the most common infectious complications, followed by soft-tissue infections [20]. At this point, special attention to both pneumonia and soft-tissue infections in tocilizumab users is required.

The limitations of the present study mainly arise from its observational design. Channelling or allocation bias [21], resulting from preferential use of a particular agent in patients with a better or worse prognosis, should be considered in the present study. First-line tocilizumab users were less often on concurrent MTX therapy. It is likely that treating physicians chose patients who could not tolerate MTX as candidates for tocilizumab therapy. These MTX-naïve patients may have been more likely to respond to any further treatment compared with MTX-refractory patients. We addressed this problem with logistic regression models adjusted for MTX use after which tocilizumab use was still associated with a higher OR of attaining DAS-28-ESR remission. This indicates that the higher DAS-28-ESR remission rates observed in the first-line tocilizumab group were due to medication rather than patient selection. Finally, the tocilizumab group was substantially smaller than the TNF inhibitors-combined group and had a shorter follow-up period. This is likely due to shorter experience with tocilizumab, approved in Japan in 2008, compared with TNF inhibitors, which have been in clinical use since 2003. As clinical experience with tocilizumab grows, future follow-up studies are warranted.

In conclusion, the present study suggests tocilizumab has drug survival and safety profiles similar to those of TNF inhibitors in clinical practice. Although a higher rate of DAS-28-ESR remission was observed in the tocilizumab group, DAS-28-ESR remission achieved with tocilizumab may be different from that achieved with TNF inhibitors, given that the ESR component of the composite score was heavily affected by tocilizumab. This problem may be addressed by using the newly suggested Boolean remission criteria, which we anticipate will be the preferred method, along with SDAI and CDAI, in the years to come. Further studies are needed to clarify the clinical implications of discrepant remission rates and the validity of the new remission criteria.

Disclosure statement: M.K. has received honoraria from Tanabe-Mitsubishi Pharma, Pfizer, Eisai and Chugai Pharma. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hetland ML, Christensen IJ, Tarp U, et al. Direct comparison of treatment responses, remission rates, and drug adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab: results from eight years of surveillance of clinical practice in the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:22–32. doi: 10.1002/art.27227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:762–84. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:964–75. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimoto N, Kishimoto T. Interleukin 6: from bench to bedside. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:619–26. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishimoto N, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, et al. Study of active controlled tocilizumab monotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate (SATORI): significant reduction in disease activity and serum vascular endothelial growth factor by IL-6 receptor inhibition therapy. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19:12–9. doi: 10.1007/s10165-008-0125-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh JA, Beg S, Lopez-Olivo MA. Tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis: a Cochrane systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:10–20. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergman GJD, Hochberg MC, Boers M, Wintfeld N, Kielhorn A, Jansen JP. Indirect comparison of tocilizumab and other biologic agents in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:425–41. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salliot C, Finckh A, Katchamart W, et al. Indirect comparisons of the efficacy of biological antirheumatic agents in rheumatoid arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or to an anti-tumour necrosis factor agent: a meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:266–71. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.132134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue E, Yamanaka H, Hara M, Tomatsu T, Kamatani N. Comparison of Disease Activity Score (DAS) 28-erythrocyte sedimentation rate and DAS28-C-reactive protein threshold values. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:407–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.054205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:573–86. doi: 10.1002/art.30129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobsson LTH, Hetland ML. New remission criteria for RA: “modern times” in rheumatology—not a silent film, rather a 3D movie. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:401–3. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.145607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Rheumatology, University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. DAS-SCORE.NL. Home of the DAS. http://www.reuma-nijmegen.nl/ (14 June 2011, date last accessed)

- 13.Smolen JS, Aletaha D. The assessment of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:S18–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Schiff MH, et al. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology. 2003;42:244–57. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aletaha D, Nell VPK, Stamm T, et al. Acute phase reactants add little to composite disease activity indices for rheumatoid arthritis: validation of a clinical activity score. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R796–806. doi: 10.1186/ar1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishimoto N, Takagi N. Assessment of the validity of the 28-joint disease activity score using erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) as a disease activity index of rheumatoid arthritis in the efficacy evaluation of 24-week treatment with tocilizumab: subanalysis of the SATORI study. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20:539–47. doi: 10.1007/s10165-010-0328-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab and attainment of remission: the role of acute phase reactants. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:43–52. doi: 10.1002/art.27740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamanaka H, Tanaka Y, Inoue E, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis patients seen in daily clinical practice in Japan: results from a retrospective study (REACTION study) Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21:122–33. doi: 10.1007/s10165-010-0366-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell L, Chen C, Bhagat SS, Parker RA, Ostör AJK. Risk of adverse events including serious infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tocilizumab: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatology. 2011;50:552–62. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Post-marketing surveillance program of tocilizumab for RA in Japan interim analyses of 3,881 patients [abstract] Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(Suppl. 10):399. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudson M, Suissa S. Avoiding common pitfalls in the analysis of observational studies of new treatments for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:805–10. doi: 10.1002/acr.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]