Abstract

Objective:

To determine the incidence of meralgia paresthetica (MP) and its relationship to diabetes mellitus (DM) and obesity.

Methods:

A population-based study was performed within Olmstead County Minnesota, from January 1, 1990, to December 31, 1999. MP incidence and its association with age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and DM were reviewed.

Results:

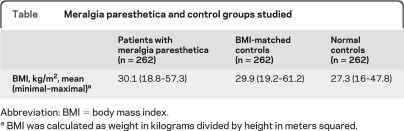

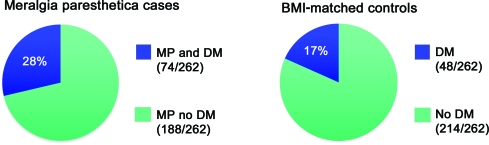

A total of 262 patients with MP, 262 normal controls, and 262 BMI-matched normal controls with mean age of 50 years were identified (51% men). The age- and sex-adjusted incidence of MP was 32.6 per 100,000 patient years, whereas the incidence of MP in people with DM was 247 per 100,000 patient years, 7 times the occurrence of MP in the general population. Of the patients with MP, 28% had DM vs 17% of BMI-matched controls and the majority of people with MP developed DM after the diagnosis of MP. Patients with MP are 2 times more likely to develop DM (odds ratio 2, 95% confidence interval 1.3–3.0, p = 0.0027). The mean BMI of patients with MP (30.1 kg/m2, obese class I) was significantly higher than that of age- and gender-matched controls (27.3 kg/m2, overweight). MP incidence increased 12.9 per 100,000 patient years in the hemidecade study period with an associated increase in both BMI (2.2 kg/m2) and average age (3 years).

Conclusions:

MP is a frequent painful neuropathy associated with obesity, advancing age, and DM. The incidence rate of MP is predicted to increase as these demographics increase in world populations. Because MP associates with DM beyond weight- and age-matched controls, more aggressive counseling of these patients in prevention of DM may be warranted.

Meralgia paresthetica (MP), literally thigh pain, refers to a mononeuropathy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.1–3 Patients have disabling or distracting pain, burning, numbness, and decreased sensation over the anterolateral thigh that often limits daily activities and sleep. Although the cause of MP is often unclear,4 it is commonly thought to be due to entrapment or compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Anecdotally, MP has been reported to associate with obesity, DM, and other entrapment etiologies including pregnancy, the wearing of tight clothes, and leaning against hard objects.5 However, these associations are based on very limited study,2 and there has only been one previous case-control study that investigated incidence rates and determinants of MP.6 As world populations experience increased rates of obesity and DM,7 the incidence of MP might be expected to increase if there is a true association. The aims of this study were to determine the incidence rate of MP in the general population and to elucidate any relationship among MP, obesity, and DM.

METHODS

Study setting.

Olmsted County is situated in southeastern Minnesota. At the time of the 1990 US Census, Olmstead County had ∼106,000 residents, which increased to 124,000 at the 2000 US Census. The majority of the county's population resides in Rochester, with the remainder in surrounding rural areas. In 2000, 90% of the population was non-Hispanic white with a median age of 35 years. The residents of Olmsted County are socioeconomically similar to the US white population although a higher proportion of residents are employed in health care services (24% compared with 8% nationwide), and the level of education is higher (30% completed college compared with 21% nationwide). Comparison of previous population-based studies of various diseases in Olmstead County with those from other US communities indicates that results from the Olmstead County population can be extrapolated to a large part of the US population.8 Epidemiologic research in Olmstead County is made possible through the Rochester Epidemiology Project. The Rochester Epidemiology Project is an uncommon data resource supported by the NIH whereby between 90 and 96% of all health care in Olmstead County is electronically searchable.8,9 Each year, more than half of the population is examined, within any 3-year period more than 90% of Olmstead County residents are seen, and by 10 years nearly all residents are seen.8

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Institutional review board approval was obtained by the institutional review boards of Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center, and participants' written informed consent to be included in research was verified in the medical chart. Patients who had requested exclusion from research were excluded from the study.

Ascertainment of MP.

All county residents diagnosed with MP (lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy) from January 1, 1990, to December 31, 1999, were identified through the diagnostic index, using H-ICDA-8 codes 3551–11 and 3576–11-2. The complete original medical records of each patient were evaluated to confirm diagnosis of MP and to obtain date of diagnosis, age, and gender. Height and weight were used to calculate BMI at the time of diagnosis, and it was ascertained whether the patient was previously, concurrently, or subsequently diagnosed with DM.

Matched control populations.

After identification of 262 patients with MP, we identified 2 groups of controls from the study population, including 262 normal controls and 262 BMI controls (table). The inclusion criterion for both control groups was that the individual had never been diagnosed with MP. For the normal control group, age and gender were matched, and BMI was recorded. For the BMI control group, in addition to matching age and gender, BMI was matched within 2 BMI points of the patient with MP and within the same standard World Health Organization–defined adult BMI subgroup.10 To confirm that BMI numbers were statistically comparable between the BMI controls and patients with MP, the BMI results were compared using the independent group t test. The original and complete medical records of each control were evaluated for previous, concurrent, or subsequent DM diagnosis.

Table.

Meralgia paresthetica and control groups studied

Abbreviation: BMI = body mass index.

BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Statistical analysis.

For the purpose of calculating incidence rates, the entire Olmstead County population was considered at risk. Confirmed cases of MP were included in the numerator and the denominator, age- and sex-specific person-years, was estimated from decennial census data. Incidence rates were calculated by gender, DM status, and BMI groupings, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) and SEs were calculated using Poisson regression models.11 Because of the transient nature of MP among patients and incomplete medical records of others, we were unable to confirm with certainty how long all patients continued to have MP, making prevalence calculation not possible. BMI data from patients with MP and DM was compared to those without DM to determine whether any statistical difference in BMI was present. In addition, BMI data of patients with MP were compared with those of the normal controls to evaluate whether there was a significant difference in BMI.

For the purpose of comparing patients with MP with BMI-matched controls, conditional logistic regression analysis was used to ascertain whether there was any association between DM and MP and to determine whether the relationship between MP and DM was independent of BMI.

RESULTS

The query of the diagnostic index database yielded a total 298 patients with MP of whom 36 were excluded because of an incomplete medical chart or an inconclusive MP diagnosis. A total of 262 patients, 129 (49%) women and 133 (51%) men, with a new diagnosis of MP were included in this study. The mean age at diagnosis was 50 years, and the mean BMI of patients with MP was 30.1 kg/m2. Subacute onset of MP pain brought patients to medical attention. The pain tended to be stagnant, nonpositional, and distracting throughout the day and did not worsen with positions such as standing or walking. Less than half of patients had clinical follow-up documented, and among those for whom serial examination was available spontaneous remission was typical. Reports of associated weight gain, loss, or systemic complaint of orthostasis or other autonomic features were absent.

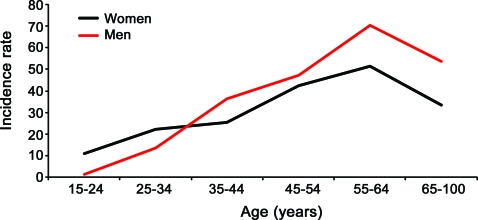

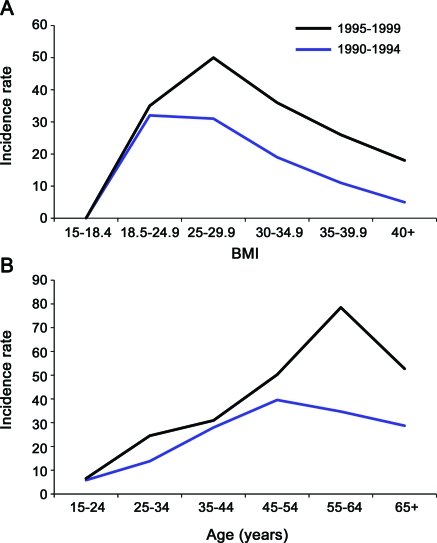

The overall age- and sex-adjusted incidence of MP was 32.6 per 100,000 patient years, and there was no significant difference in the incidence rates when stratified by gender (p = 0.29).The age group of 55–64 years had the highest incidence of MP in both men and women (figure 1). Incidence rates, BMI, and age increased significantly over the study period (p < 0.001) (figure 2).

Figure 1. Age- and gender-adjusted incidence rates per 100,000 patient years of meralgia paresthetica (MP).

The incidence rate of MP between men and women was not statistically different. The age group of 55–64 years had the highest incidence of MP in both males and females.

Figure 2. Incidence rates increased significantly over the study period from 23.52 per 100,000 patient years in 1990–1994 to 36.38 per 100,000 patient years in 1995–1999 (p < 0.001).

(A) The noted increase correlated with an increase in body mass index (BMI) during the same period. The mean BMI of patients with meralgia paresthetica from 1990 to 1994 was 28.7 kg/m2 (overweight), and 30.9 kg/m2 (obese class I) from 1995 to 1999 (p = 0.005). (B) Age increase was borderline significant over the study period, increasing an average of 3 years (p = 0.049). Average age was 48 years from 1990 to 1994 and 51 years from 1995 to 1999.

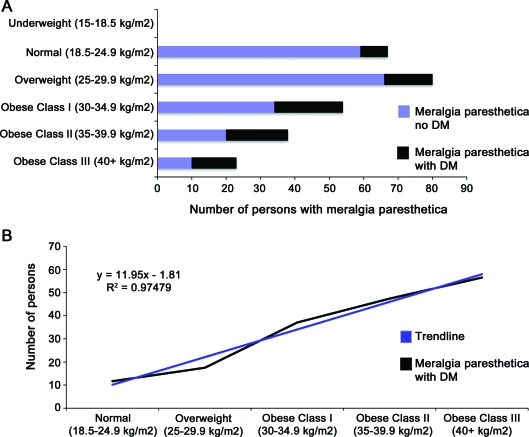

To confirm the association between occurrence of MP and BMI, we analyzed the relationship of MP, obesity (measured by BMI), and DM. The MP data are summarized in figure 3. The mean BMI of all patients was MP was 30.1 kg/m2 (range 18.8–57.3 kg/m2), whereas the mean BMI of the normal controls was significantly lower at 27.3 kg/m2, confirming the association of MP with BMI (odds ratio [OR] 1.2, 95% CI 1.04–1.44). Furthermore, the higher average BMI of patients with MP and DM compared with those without DM (33.8 vs 28.8 kg/m2, respectively, p < 0.001), is consistent with the association between DM and BMI.

Figure 3. Occurrence of meralgia paresthetica (MP) in relation to body mass index (BMI) calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared and diabetes mellitus (DM).

There is strong association between BMI and occurrence of MP. (A) BMIs are plotted against the number of patients with MP. No patients with MP were underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2). The lowest BMI was 18.8 kg/m2 and the highest was 57.3 kg/m2. The mean BMI of all patients with MP was 30.1 kg/m2. The mean BMI of patients with MP without DM was 28.8 kg/m2, whereas the mean BMI of patients with MP and DM was 33.8 kg/m2. (B) The percentage of patients with DM and MP as a proportion of all patients with MP increases as BMI increases in a linear fashion (R2 = 0.97).

To investigate a possible association between MP and DM, we checked the occurrence of MP over the ensuing 10 years, in all patients who had a standing diagnosis of DM in 1990, As of January 1, 1990, 973 individuals older than age 45 in Olmstead County had DM.12 During the 10-year study-period, 24 of them were subsequently diagnosed with MP, making the incidence rate of MP in the DM population 247 per 100,000 patient years. This incidence rate is more than 7½ times the occurrence in the general population (32.6 per 100,000 patient years) and demonstrates that MP is significantly associated with DM (p = 0.0012). Furthermore, it was found that patients with MP are ∼2 times more likely to have DM than age-, gender-, and BMI-matched controls (OR 2, 95% CI 1.3–3.0, p value = 0.0027) (figure 4).

Figure 4. Meralgia paresthetica (MP) is significantly associated with diabetes mellitus (DM).

Shown on the left is occurrence of DM in patients with MP in this study. On the right are matched controls for equivalent age, gender, and body mass index (BMI). BMI is calculated by weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Among patients with MP, DM was twice as likely to occur compared with their matched controls.

Of the 74 patients with both MP and DM, 64.9% (n = 48) developed DM after the diagnosis of MP. Thus almost 1 of 5 (48 of 262) patients with MP went on to develop DM in the 10-year study period, further underlining the significant association between MP and DM. Hemoglobin A1c (HBA1c) levels within 2 years of MP diagnosis were abstracted in those patients who had DM. Among 74 MP patients with DM, 38 had HBA1c levels available. The range of HBA1c levels varied widely from 5.0 to 14.1, with median HBA1c of 7.1.

DISCUSSION

This is a population-based study investigating incidence rates and determinants of MP in the United States. Results indicate that the painful sensory mononeuropathy is not a rare disease, occurring in 32.6 per 100,000 patient-years. The incidence rate of MP seems to be the highest in overweight persons in their fourth to sixth decade of life. MP incidence rates trended up over the 10-year study period in conjunction with an aging and increasingly obese population, suggesting that MP will become more common as the population of the United States becomes older and heavier.7,13

A population-based study performed in the Netherlands6 examined incidence rates and risk factors of MP in the primary care setting. Although the Netherlands study found a similar incidence rate of MP (4.3 per 10,000 person years), they concluded that there was no association between obesity and MP.6 However, it does not appear that height and weight were available for all their patients. In our study, only a minority of obese persons were coded as obese, and a recent large study showed that only 20% of obese persons had medical documentation of obesity, emphasizing the problem of underdocumentation in medical practice.14 With the use of height and weight of each individual, our study observed a statistically significant difference between the BMI of patients with MP and the BMI of age- and sex-matched controls, with no underweight persons having MP.

MP has been commonly tied to DM in clinical textbooks,15 and this population-based study demonstrated in detail a strong association between MP and DM. The incidence rate of MP in the diabetic population was more than 7½ times that of the general population. In addition, multivariate conditional logistic regression analysis that included BMI, gender, and age as covariates showed that DM is an independent risk factor for the development of MP. In our population, patients with MP were almost twice as likely to develop DM as matched controls, and approximately two-thirds of patients with both MP and DM developed DM after diagnosis of MP. This finding raises the question of whether MP may be a preclinical expression of DM. Therefore, a diagnosis of MP suggests that a search for underlying DM is warranted, and special efforts to prevent its emergence are indicated.

Because this study is retrospective, certain limitations exist in understanding of disease pathogenesis. Possible pathogenic mechanisms include 1) mechanical compression by obesity, 2) nerve injury susceptibility by chronic hyperglycemia, or 3) even inflammatory causes. Inflammation had been proposed by Wartenberg3 as a possible mechanism of MP years earlier, and, more recently, nerve inflammation in both diabetic and nondiabetic femoral predominant amyotrophy has been observed.16 In future consideration of MP pathogenesis, either a fortuitous pathologic specimen or modern imaging17 may be helpful in discerning inflammation or compressive mechanisms among patients with MP.

The epidemiologic association between advancing age, obesity, DM, and MP is important. That importance is emphasized by the observation that DM appears to be an independent risk factor for the development of MP, and patients who have both MP and DM tend to develop MP before DM. A painful numb thigh from MP may be the first medical complication of overweight status and provide clinicians an opportunity to begin the conversation of the importance of weight reduction. If a clinician identifies a patient with MP without DM, more aggressive counseling may be warranted to reduce the risk of development of DM.

GLOSSARY

- BMI

body mass index

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- HBA1c

hemoglobin A1c

- MP

meralgia paresthetica

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Parisi: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, and statistical analysis. Dr. Mandrekar: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, and statistical analysis. Dr. Dyck: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, and statistical analysis. Dr. Klein: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, study supervision, and obtaining funding.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Parisi and Dr. Mandrekar report no disclosures. Dr. Dyck has received research support from the NIH/NINDS. Dr. Klein serves on the editorial board of the Journal of Peripheral Nerve Society; served as a consultant for Pfizer Inc; and receives research support from the NIH/NINDS.

REFERENCES

- 1. Harney D, Patijn J. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and management strategies. Pain Med 2007;8:669–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grossman MG, Ducey SA, Nadler SS, Levy AS. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:336–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wartenberg R. Meralgia paresthetica. Neurology 1956;6:560–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goetz CG. Textbook of Clinical Neurology, 3rd ed Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bradley WG. Neurology in Clinical Practice, 5th ed Philadelphia: Butterworth-Heinemann/Elsevier; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Slobbe AM, Bohnen AM, Bernsen RM, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Incidence rates and determinants in meralgia paresthetica in general practice. J Neurol 2004;251:294–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA 2010;303:235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Melton LJ., 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:266–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kurland LT, Molgaard CA. The patient record in epidemiology. Sci Am 1981;245:54–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2000;894:1–253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frome EL, Checkoway H. Epidemiologic programs for computers and calculators: use of Poisson regression models in estimating incidence rates and ratios. Am J Epidemiol 1985;121:309–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leibson CL, O'Brien PC, Atkinson E, Palumbo PJ, Melton LJ., 3rd. Relative contributions of incidence and survival to increasing prevalence of adult-onset diabetes mellitus: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol 1997;146:12–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Landefeld CS, Winker MA, Chernof B. Clinical care in the aging century: announcing “Care of the aging patient: from evidence to action.” JAMA 2009;302:2703–2704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bardia A, Holtan SG, Slezak JM, Thompson WG. Diagnosis of obesity by primary care physicians and impact on obesity management. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:927–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ropper AH, Adams RD, Victor M, Samuels MA. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology, 9th ed New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dyck PJ, Windebank AJ. Diabetic and nondiabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathies: new insights into pathophysiology and treatment. Muscle Nerve 2002;25:477–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Amrami KK, Felmlee JP, Spinner RJ. MRI of peripheral nerves. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2008;19:559–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]