Abstract

The GnRH system represents a useful model of long-term neural plasticity. An unexplored facet of this plasticity relates to the ontogeny of GnRH neural afferents during critical periods when the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis is highly susceptible to perturbation by sex steroids. Sheep treated with testosterone (T) in utero exhibit profound reproductive neuroendocrine dysfunctions during their lifespan. The current study tested the hypothesis that these changes are associated with alterations in the normal ontogeny of GnRH afferents and glial associations. Adult pregnant sheep (n = 50) were treated with vehicle [control (CONT)] or T daily from gestational day (GD)30 to GD90. CONT and T fetuses (n = 4–6/treatment per age group) were removed by cesarean section on GD90 and GD140 and the brains frozen at −80°C. Brains were also collected from CONT and T females at 20–23 wk (prepubertal), 10 months (normal onset of puberty and oligo-anovulation), and 21 months (oligo-anovulation in T females). Tissue was analyzed for GnRH immunoreactivity (ir), total GnRH afferents (Synapsin-I ir), glutamate [vesicular glutamate transporter-2 (VGLUT2)-ir], and γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA, vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT)-ir] afferents and glial associations (glial fibrillary acidic protein-ir) with GnRH neurons using optical sectioning techniques. The results revealed that: 1) GnRH soma size was slightly reduced by T, 2) the total (Synapsin-I) GnRH afferents onto both somas and dendrites increased significantly with age and was reduced by T, 3) numbers of both VGAT and VGLUT inputs increased significantly with age and were also reduced by T, and 4) glial associations with GnRH neurons were reduced (<10%) by T. Together, these findings reveal a previously unknown developmental plasticity in the GnRH system of the sheep. The altered developmental trajectory of GnRH afferents after T reinforces the notion that prenatal programming plays an important role in the normal development of the reproductive neuroendocrine axis.

The development of reproductive activity in mammals can be modified by gonadal steroids during restricted, species-specific stages of development; thus, leading to the identification of critical periods (1, 2). Sex behaviors and the appearance of the external genitalia are perhaps the best studied of the events that can be manipulated by gestational exposure to, or removal of, gonadal steroids. Indeed, it is well known that both male and female phenotypic sex characteristics are established before puberty, with varying time courses depending on the species examined (2). Reproductive neuroendocrine functions, like those of sex behaviors, are also influenced by exposure to sex steroids early in development (3). In female rats, monkeys, and sheep, a disruption of the preovulatory LH surge is observed after prenatal steroid manipulations (4–6). In male nonhuman primates, a surge-like release of gonadotropins can be produced experimentally by estrogen after prepubertal gonadectomy, suggesting that the preovulatory surge in primates is not sexually differentiated (5, 7). In those species in which the surge mechanism is sexually differentiated, the alterations of preovulatory surge events, and perhaps behavior, are likely the result of alterations in GnRH neurocircuitry, specifically, steroid signaling pathways and specific GnRH afferents (8, 9).

As a model of adult reproductive neuroendocrine dysfunction (endocrinopathy) after prenatal testosterone treatment (T), the sheep has become an important experimental animal for understanding how events occurring prenatally impact the timing of the onset of puberty and quality of the reproductive lifespan. Specifically, female sheep exhibit a normal onset of puberty (defined by a normal onset of ovarian cycles) but show progressive loss of ovarian cyclicity (10). An impact on the GnRH/LH surge system is suggested based on the severely attenuated or completely absent surge (11, 12). It is becoming clear that sequelae of T exposure in utero are manifested later in the reproductive lifespan. These disturbances after puberty therefore appear to conform to the established principles of fetal “programming” (13).

Given that GnRH neurons represent the final common pathway in the neural control of reproduction, it is reasonable to hypothesize that prenatal T and its accompanying reproductive disruptions reflect actions on these neurons directly or on neurons interacting with them (i.e. afferents). It has already been established that prenatal T in sheep does not alter the numbers or gross morphology of GnRH neurons in ovariectomized T females (14). However, the altered steroid feedback observed in these T females (15, 16) would be expected to reflect altered numbers/types of neural afferents to GnRH neurons. Indeed, such changes have previously been found in the adult sheep when comparing breeding and nonbreeding seasons (17–19) when pronounced changes occur in GnRH activity (20). Although various aspects of the ontogeny of the sheep GnRH system have been previously characterized (Fig. 1) (21–24), the neurocircuitry of GnRH afferents and the relationship between GnRH neurons and glial cells during development has not been examined. Because GnRH activity in sheep varies not only in the adult but also prenatally (25), it is important to determine whether these changes are the result of developmental plasticity, and if so, whether this plasticity is modifiable by T.

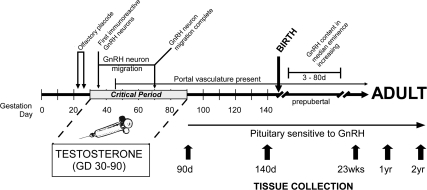

Fig. 1.

Timeline of development of the GnRH system in sheep with important milestones identified (for additional details, see Refs. 21–24). Also shown are the gestational ages (GD) when T or oil was administered and the ages of females at the time of tissue collection.

The present study therefore was undertaken to address two important questions. First, what is the normal ontogeny of total (unidentified phenotype) and specific [glutamateric, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic] GnRH inputs and glial associations with GnRH neurons in the female sheep? Second, are these associations subject to modification by exposure to excess prenatal T? The results of our study implicate programming of the sheep's reproductive lifespan vis-à-vis central modulation of GnRH afferents.

Materials and Methods

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Animal Care and Use Committee and performed according to the guidelines established in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council (National Academy Press, 1996). Naturally cycling adult Suffolk female sheep were maintained outdoors at the Reproductive Sciences Sheep Research Facility of the University of Michigan. Females were mated as confirmed by paint markings transferred from the male. Beginning on gestational day (GD)30 and continuing until GD90 (d 147 is term) (Fig. 1), pregnant females were injected twice weekly with either T propionate (T, 100 mg/sheep, im) or vehicle [control (CONT)] (corn oil) (26). This produced circulating levels of T in the adult male range in the mother and fetal male range in female fetus (27). Brains from fetuses at GD90 [n = 10 (5 T, 5 CONT)] and GD140 [n = 10 (5 T, 5 CONT)] removed by cesarean section and immediately euthanized were used in this study (27). Although brains were collected, in the case of twins or triplets, only the brain from one fetus was randomly chosen for analysis to eliminate any selection bias. The brains were frozen in a mixture of dry ice and isopentane and stored at −80 C until processed. Postnatal lambs at 23 wk of age [n = 8 (4 T, 4 CONT)] and adult female sheep during the first [10 months, n = 10 (5T, 5 CONT)] and second [21 months, n = 12 (6 T, 6 CONT)] breeding seasons (in January) were administered two injections of prostaglandin-F2α 11 d apart during the breeding season and euthanized 26 h after the second injection, during the presumptive follicular phase and near the expected onset of the GnRH/LH preovulatory surge in CONT animals. At the time of euthanasia, all CONT animals were cycling, and the prenatal T animals were oligo- or anovulatory based on twice weekly measures of progesterone (28). All animals were then deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital and the brains collected as described above. Brains were sectioned at a thickness of 25 μm using a cryostat and thaw mounted onto SuperFrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), boxed, and stored at −80 C until processed for immunofluorescent detection of GnRH, presynaptic markers, and glial cells.

Immunofluorescence

The antibodies used in the current study (Supplemental Table 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org) were identical to those described previously by our laboratory (17, 18). The general immunocytochemistry procedure was also similar to that used previously (18) with several modifications to facilitate the use of slide-mounted sections compared with free-floating ones. These modifications included: 1) fixing frozen sections for 15 min in cold (4 C) freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (PB) [0.1 m (pH 7.3)] and 2) adjusting the primary antibody concentrations for use with the slide-mounted sections to optimize staining intensity while maintaining the lowest level of background staining (dilutions are listed in Supplemental Table 1). The specificity of all of the antibodies for use in sheep tissue has been previously described (17, 18). Furthermore, to ensure that the new fixation procedure did not negatively impact immunostaining, the vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGLUT2) and vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) antibodies were preabsorbed with purified antigens (10 μg) before incubation with tissue sections in the current study to confirm their specificity. Lastly, the putative synaptic localization of VGLUT2 and VGAT was determined using tissue dual-labeled for Synapsin-I (Syn-I) and either VGLUT2 or VGAT. Before application of antibodies to the slides, the edges of each slide were briefly dried to remove excess buffer and then a small well (∼1 mm in depth) was made around the slide using a PAP pen (Research Products International, Mt. Prospect, IL). Antibody cocktails were then diluted in PB containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 15% serum and applied directly to the slides in the PAP well. A small piece of Parafilm was then placed over each slide; the Parafilm adhered to the PAP well to form a seal over the tissue. The slides with Parafilm coverslips were then placed onto small plastic blocks and the blocks placed into Tupperware containers. A few pieces of damp paper towel were placed in the bottom of the Tupperware chamber to maintain humidity, and then the chamber was sealed. Chambers were incubated statically (i.e. without agitation) at 4 C for approximately 68–72 h. After incubation in primary antibodies, the coverslips were removed, and the slides were transferred to plastic slide mailers for all subsequent steps. Slides were first rinsed in PB, five times 5 min each with gentle agitation facilitated by standing the slide mailers in a beaker and setting the beaker on a shaking platform. The slides were incubated in a cocktail of secondary antibodies diluted 1:200 (Supplemental Table 1) at room temperature for 60 min with shaking. After additional washes, the slides were air dried overnight in the dark. On the next day, slides were briefly dipped in distilled water to remove buffer salts and then coverslipped with Prolong antifade solution containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Slides were allowed to dry for at least 3 d in the dark at room temperature before imaging.

Imaging and analysis

Slides were viewed and analyzed essentially as previously described by our laboratory using a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope and optical sectioning (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) (18). Briefly, individual GnRH neurons (n = 7–15/animal) within the medial preoptic area were viewed at ×20 magnification under epifluorescence illumination. Next, a GnRH neuron was selected, and the microscope was switched to confocal mode for imaging of individual identified GnRH neurons using a ×63 (1.4 NA) water immersion objective. All images were captured using the multitrack mode to eliminate bleed-through of fluorescent signals. Detector gain, amplitude offset, and amplifier gain were normalized for each channel on each z-stack to a relative fluorescence intensity range of 0–255 with a small percentage of darkest and brightest pixels (1–2%). Pinhole diameters were first set to 1 Airy Disk and then adjusted to match the thickness of optical sections for all channels. Eight-bit confocal images were acquired with a frame size of 1024 × 1024 pixels using a scan speed of 6 μsec, 1× line averaging and 1× zoom mode. No additional filtering was applied. All serial Z-sections were taken at a thickness of 0.38 μm and the files stored on CD. Images were processed using National Institutes of Health ImageJ software with the same functions used [rolling ball background subtraction (29), colocalization, point selection] as previously described (18). Analyses were performed on three to five optical sections for each GnRH neuron. In addition, glial associations with GnRH neurons were quantified as follows. After applying background subtraction and removal of the third channel (i.e. either Syn-I, VGAT, or VGLUT2) from the z-stack, each channel was converted to grayscale. First, the GnRH channel was selected, and 10 points were randomly selected on the periphery of the GnRH soma (dendrites were not analyzed) using the multipoint selection tool. Next, the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) channel was selected and thresholds determined as previously described (17). The gray value for each point previously selected in the GnRH channel was then determined in the GFAP channel. Only those GFAP gray values above threshold were used. When a GFAP/GnRH point gray value exceeded the threshold, it was assigned a value of 1 and if below threshold, a value of 0. For each of three to five optical sections from three to five GnRH neurons per animal per age group, an average value was calculated. The overall means were expressed as a percentage of GnRH neuronal soma apposed by glial processes. To validate our newer method of determining the amount of glial apposition on GnRH neurons, we analyzed 25 neurons (five from each age group) from 25 randomly selected sections triple-labeled for GnRH, Syn-I, and GFAP and compared these results with those obtained on the same sections using our earlier method (17). Briefly, the length of the GnRH cell membrane length was determined in three to five optical sections from each neuron. Then, the total length of glial pixels apposed to the GnRH membrane was determined using only those pixels not separated by a Syn-I pixel. The percent of GnRH membrane apposed by glial fibrils was then computed. For the same neurons and optical sections, our newer procedure (described above) was used. The mean apposition values derived from each method were compared by t test and the relationship between the two measures determined by Pearson correlation analysis. The results of this comparison revealed that the two measures (total membrane length vs. point selection) yielded similar estimates of percent of glial apposition (83.1 ± 1.5 vs. 87.0 ± 1.9, respectively; t48 = 1.68, P > 0.05, Supplemental Fig. 1). The correlation between estimates using the two methods was statistically significant (r = 0.80, P < 0.0001). Together, these results suggest that the percent of glial apposition can be reliably determined using either method despite differences in the absolute amount of GnRH neuronal membrane being analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Means ± sem for each parameter from the sample of GnRH neurons for each ewe were determined, and then the group mean data were analyzed using t test (age) or two-way ANOVA (age, treatment, interaction). Bonferroni post hoc analyses were performed when appropriate. Data were analyzed using Prism for the Macintosh (version 5.0c; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Differences were considered significant if P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Reproductive phenotype

Females treated with T in utero exhibited masculinization of the external genitalia as previously described (26). Additional details pertaining to the phenotypes and a description of the differences between T and CONT female sheep can be found in Ref. 28, which addresses cyclic behavior of these animals over 2 yr (brains from nos. 139, 224, and 268 CONT and 209, 210, and 213 T are examples of animals from which brains were used for this study). Perivoulatory changes from the large cohort, from which the subsets for neuroanatomical studies were derived, have been reported previously (30).

Antigenic localization and antibody specificity

Immunoreactive VGLUT 2 and VGAT terminals were extensively colocalized with Syn-I in dual-labeled tissues confirming their concentrations in nerve terminals (Supplemental Fig. 2). No labeling of cell somas was observed (see Figs. 4 and 6). Antibodies preabsorbed with purified peptide resulted in complete loss of staining, indicating that they are specific for the intended antigen (Supplemental Fig. 3).

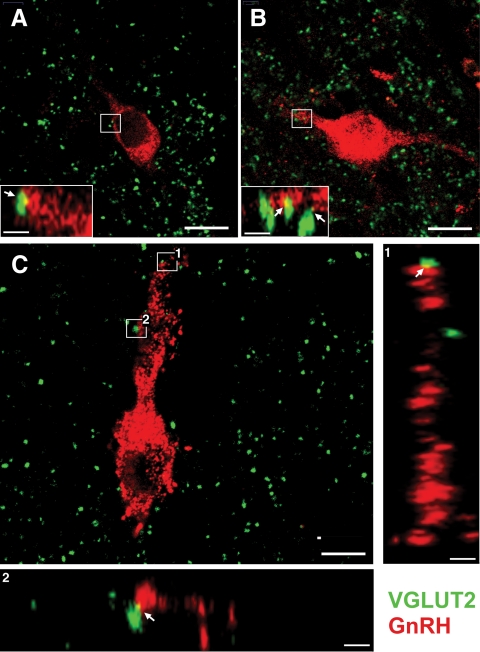

Fig. 4.

A, Single optical section from a GD140 CONT female illustrating GnRH (red)- and VGLUT2 (green)-terminal labeling. Boxed region is shown in a digitally zoomed orthogonal view to illustrate the apposition between terminals and GnRH neuron (arrows). B, Single optical section from a 10-month CONT female illustrating GnRH (red)- and VGLUT2 (green)-terminal labeling. C, Single optical section from a 10-month T female illustrating GnRH (red)- and VGLUT2 (green)-terminal labeling. Larger orthogonal views are shown with specific inputs identified by the numbers. Scale bar, 10 μm (main panels in A–C) and 2 μm (insets and large orthogonal views).

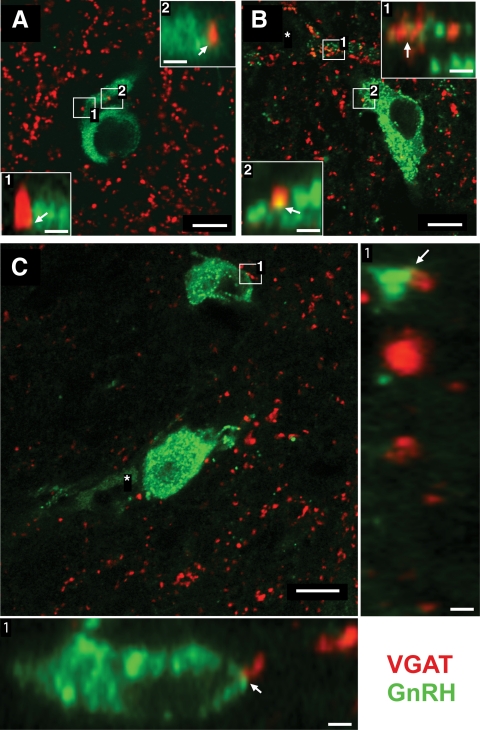

Fig. 6.

A, Single optical section from a GD140 CONT female illustrating GnRH (green)- and VGAT (red)-terminal labeling. Boxed region is shown as digitally zoomed orthogonal view to illustrate the apposition between terminals and GnRH neuron (arrows). B, Single optical section from a 10-month CONT female illustrating GnRH (green)- and VGAT (red)-terminal labeling. C, Single optical section from a 10-month T female illustrating GnRH (green)- and VGAT (red)-terminal labeling. Larger orthogonal views are shown with a specific input identified by the number. Asterisk in B and C identify adjacent GnRH neuron slightly out of the plane of view. In B, the proximal dendrite of the adjacent GnRH neuron is in the same plane of section and exhibits extensive terminal appositions that seem to envelope a GnRH filopodium (box 1). Scale bar, 10 μm (main panels in A–C) and 2 μm (insets and large orthogonal views).

GnRH neuron morphology

Immunoreactive GnRH neurons were identified in brains collected from females of all ages and treatments. Although not quantified, the location of GnRH neurons was essentially identical to that observed in adult sheep (31, 32), namely, a loosely arranged continuum extending from the medial preoptic area/organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (greatest numbers, 10–20 neurons/section) to the medial basal hypothalamus (fewest numbers, three to five neurons per section). Soma size was reduced slightly by T (F1,65 = 4.069, P = 0.048). This was manifest as a reduction (Bonferroni post hoc test, P < 0.05) in the 21-month-old T group compared with CONT females (219.5 ± 16.2 μm2 vs. 281 ± 10.3 μm2, respectively).

GnRH afferents

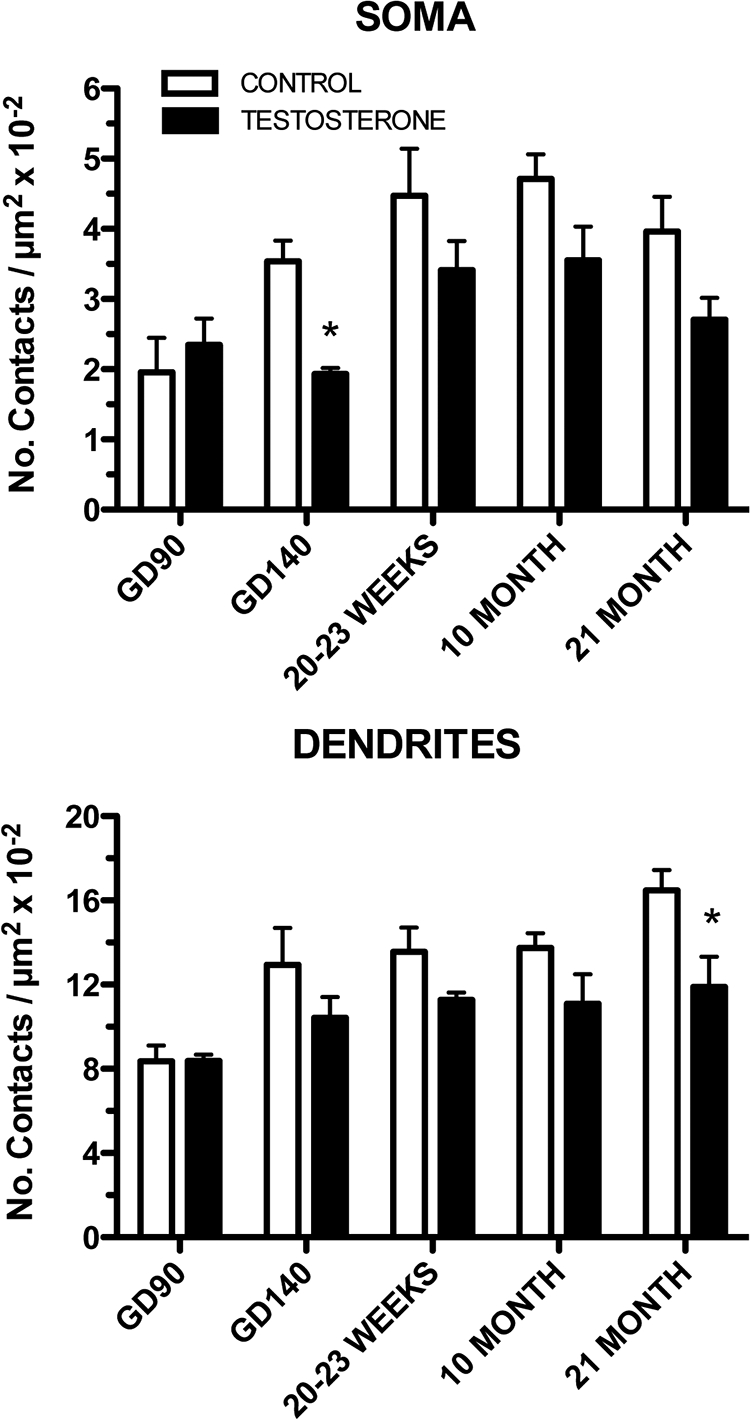

The mean total length of immunoreactive GnRH membrane (soma + dendrites) analyzed per animal was 538 ± 15 μm and was similar between age and treatment groups (data not shown). The number of total afferents [i.e. Syn-I-immunoreactive (ir)] onto GnRH somas and dendrites increased significantly with age (age, F4,30 = 7.619, P < 0.001 and F4,30 = 7.880, P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 2). Prenatal T caused an overall reduction in total (Syn-I) afferents onto GnRH cell somas and dendrites (treatment, F1,30 = 12.25, P < 0.01 and F1,30 = 12.50, P < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 2). No significant interaction between age and treatment was observed. Prenatal T caused a decrease in the number of total (Syn-I-ir) GnRH afferents (Fig. 2) at GD140 on GnRH somas and at 21 months on GnRH dendrites.

Fig. 2.

Ontogeny of Syn-I immunoreactive inputs to GnRH neurons (soma and dendrites are shown separately) for CONT and prenatal T-treated female sheep. *, P < 0.05 vs. CONT.

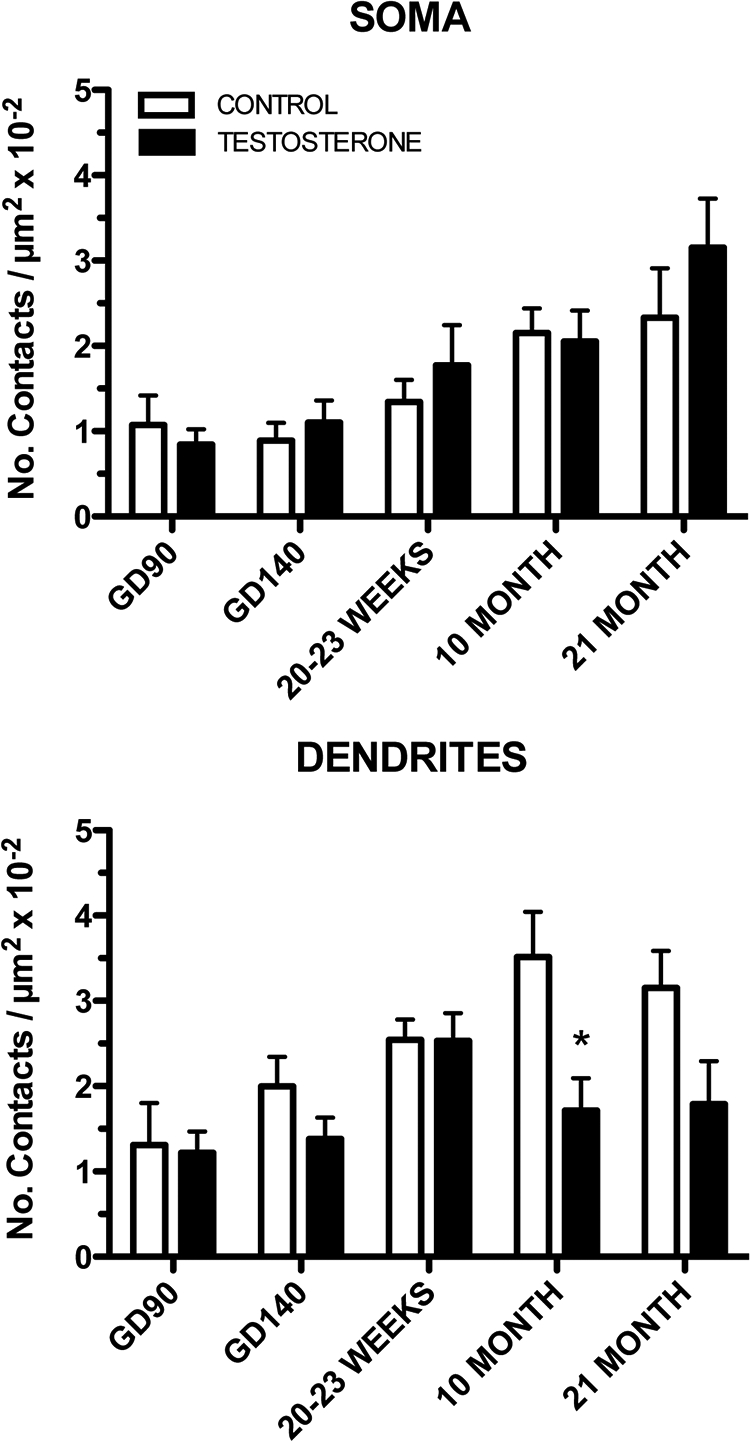

The number of glutamatergic (VGLUT2-ir) afferents onto both GnRH somas and dendrites increased significantly with age (age, F4,43 = 7.296, P < 0.001 and F4,44 = 4.015, P < 0.01, respectively) (Figs. 3 and 4, A and B). Similar to what was observed for Syn-I (total) GnRH afferents, prenatal T reduced the number of VGLUT2 afferents onto GnRH dendrites (treatment, F1,44 = 15.71, P < 0.001). However, VGLUT2 afferents onto GnRH somas were unaffected by T (Figs. 3 and 4). The suppression of inputs to GnRH dendrites was most pronounced for VGLUT2 afferents in the 10-month-old T group compared with CONT females, where a nearly 2-fold reduction was observed (Bonferroni post hoc test, P < 0.01) (Figs. 3 and 4C). Despite similar numbers of VGLUT2 inputs in the 21-month-old females, this difference did not attain significance because of a small decline in the number of VGLUT2 inputs in CONT females (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Ontogeny of VGLUT2 immunoreactive inputs to GnRH neurons (soma and dendrites are shown separately) for CONT and prenatal T-treated female sheep. *, P < 0.05 vs. CONT.

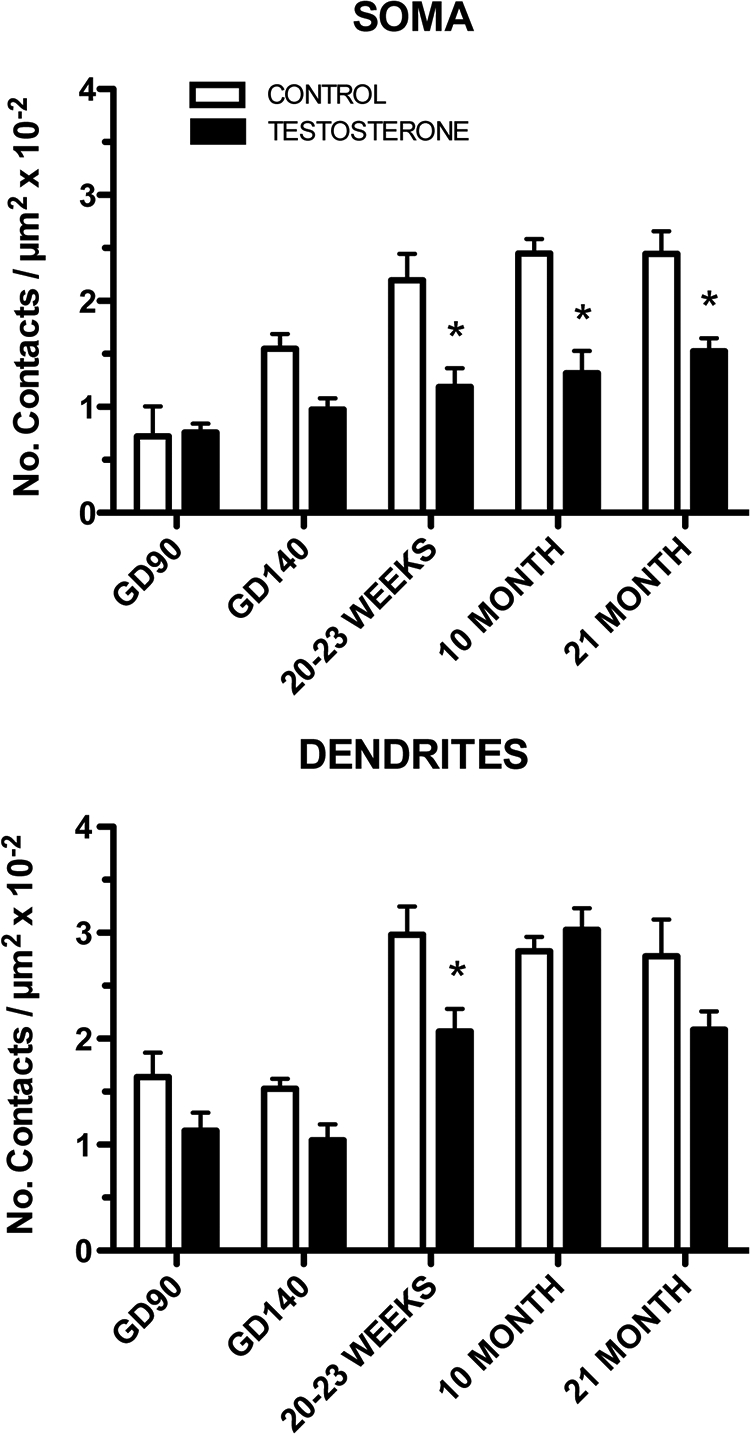

Numbers of GABA (VGAT-ir) afferents onto both GnRH somas and dendrites also increased significantly with age (age, F4,30 = 15.71, P < 0.0001 and F4,30 = 24.44, P < 0.0001, respectively) (Figs. 5 and 6, A and B). Somewhat similar to what was observed for Syn-I and VGLUT2, prenatal T resulted in a decrease in VGAT terminals onto GnRH somas and dendrites (treatment, F1,30 = 38.61, P < 0.0001 and F1,30 = 13.07, P < 0.01, respectively) (Figs. 5 and 6C). A significant interaction between age and treatment was also observed (F4,30 = 3.304, P < 0.05) for VGAT afferents onto GnRH somas, but this was not observed for inputs to GnRH dendrites. In general, the changes observed in VGAT afferents, especially onto GnRH somas, were of much greater magnitude when compared with VGLUT2 or Syn-I afferents. Changes onto GnRH dendrites differed between types of afferents and developmental age with some occurring before puberty (VGAT) and others afterwards (VGLUT2). Interestingly, comparing the proportion of VGAT and VGLUT2 afferents reveals that these account for a large percentage of total afferents (Syn-I) onto GnRH somas but only a small fraction of the total afferents onto GnRH dendrites.

Fig. 5.

Ontogeny of VGAT immunoreactive inputs to GnRH neurons (soma and dendrites are shown separately) for CONT and prenatal T-treated females. *, P < 0.05 vs. CONT.

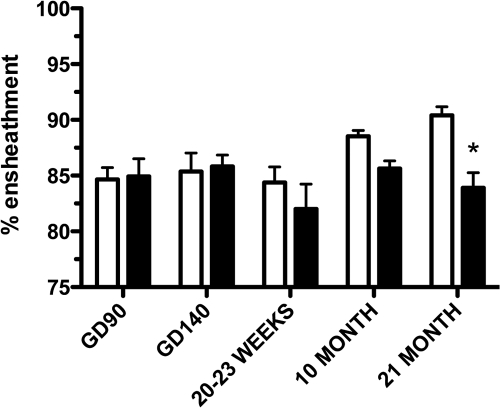

Glial associations with GnRH neurons were robust at all ages examined (Fig. 7). Nevertheless, these also varied significantly with age (Fig. 8). A slight increase in glial associations was observed between embryonic and adult ages in the CONT females (age effect, F4,30 = 3.139, P < 0.05). Prenatal T significantly blunted the age-related increase in glial associations (treatment effect, F1,30 = 6.779, P = 0.01). However, this difference was only significant in the 21-month-old T females compared with CONT (Bonferroni post hoc test, P < 0.01) (Fig. 7). The interaction between age and treatment approached significance (F4,30 = 2.293, P = 0.08).

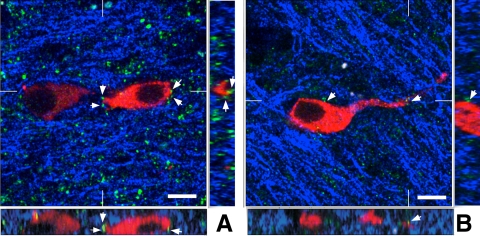

Fig. 7.

Single optical sections and corresponding orthogonal projections from a GD140 CONT female (A) and a corresponding GD140 T female (B) labeled for GnRH (red), GFAP (blue), and Syn-I (green). Note the reduction in Syn-I contacts in the T female compared with the CONT. Arrows, Syn-I inputs onto GnRH neurons. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Fig. 8.

Ontogeny of glial associations with GnRH neurons (soma only) for CONT (open bar) and T (filled bar) females. *, P < 0.05 vs. CONT.

Discussion

The results of the current investigation reveal the following. 1) A progressive increase in total (Syn-I) and identified [glutamatergic (VGLUT2) and GABAergic (VGAT)] inputs to female sheep GnRH neurons normally occurs prenatally and continues into postnatal life. 2) T plays an important role in determining both the embryonic and adult pattern of GnRH afferents in the female but has only a minor effect on GnRH neuron size. 3) Glial associations with GnRH neurons increase slightly during development and over the reproductive lifespan. Prenatal T and the resultant premature loss of reproductive function at 21 months of age were associated generally with reductions in both GnRH afferents and glial associations with GnRH neurons. Taken together, the altered trajectory of GnRH afferents, the defeminization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, and concomitant endocrinopathies expand our understanding of events occurring during the critical period of sexual differentiation in this important animal model. We speculate that the premature reproductive failure after prenatal T does not simply reflect accelerated aging but rather is the result of a discrete programming event during a critical period for reproductive lifespan.

Increases in VGLUT2 and VGAT-ir occurring postnatally in the sheep brain are similar to those described for the preoptic area and other brain regions previously in mice and rats (33, 34). The influence of T to alter this trajectory as revealed in the current study adds a new dimension and specificity to this role of the organizing hormone. Nevertheless, the precise mechanism(s) whereby prenatal T alters GnRH neurocircuitry and glial interactions with GnRH neurons remains to be elucidated. Aromatase is found in neurons of the sheep brain and is capable of converting T to estradiol before birth (35). Therefore, the programming effects described could reflect an indirect action of T resulting from T's conversion to estradiol locally. Although the present results did not address this directly, earlier work in both ovariectomized model and gonadal-intact sheep model with T have shown that many of the alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis related to estradiol negative feedback could be mimicked by exposure to the nonaromatizable androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT), thus supporting an androgenic mechanism (36, 37). On the other hand, effects of T to cause disruption of the positive feedback actions of estradiol are likely mediated by estrogenic actions of T, because they are not observed in DHT-treated females (36, 37). Estrogen negative feedback is evident at GD90 in sheep (38) at around the time that total and specific numbers of GnRH afferents are visible. The present study found that prenatal T resulted in a general reduction in total numbers of inputs and specific inputs at around GD140. The tendency for fewer numbers of GABA inputs beginning before birth would be consistent with the hypothesis that negative feedback is reduced in T females compared with CONT (12, 15, 27). Given the greater impact of T to suppress GABAergic terminals during embryonic ages compared with glutamatergic terminals, this indicates a selectivity for, or sensitivity of, the putative inhibitory GnRH afferents during this period. However, some caution is required in interpreting this change because of accumulating evidence that GABA also has excitatory functions during development (see below). Regardless, given that the number of glutamatergic plus GABAergic inputs to GnRH neurons only accounted for a fraction of GnRH dendritic afferents at any age, we conclude that an unidentified population of inputs contributes to the remaining difference in total numbers of GnRH afferents. The identity of those inputs remains to be determined.

Although typically considered the predominant inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, GABA may also exhibit neuroexcitatory actions during development (39). Moreover, recent evidence indicates that prenatal T specifically increases GABAergic drive onto GnRH neurons in mice (40, 41). Nevertheless, despite the loss of reproductive cycles produced in mice and sheep by prenatal DHT/T, it remains to be determined whether GnRH neurons and their neurocicruitry are regulated during development in an entirely equivalent manner. For example, it appears that GABA-A receptors are predominantly responsible for mediating the effects of GABA on GnRH neurons in rodents (42, 43). In sheep, on the other hand, both GABA-A and GABA-B receptors have been implicated (for review, see Ref. 44). Another important difference between species potentially relevant to the unique developmental switch between excitatory and inhibitory actions of GABA is that the switch in the rodent brain occurs postnatally (39, 45), shortly after the perinatal critical period of sexual differentiation. In sheep sexual differentiation occurs prenatally. This makes direct comparisons of the effects of in utero perturbations between species problematic in view of the different rates of development in absolute time and in relation to birth. Alternatively, it is possible that the majority of events associated with the GABA switch in the current and previous reports represent postsynaptic changes (e.g. receptor number, type, or affinity). In this scenario, pre- and postsynaptic events occur independently. However, this would seem unlikely to explain all of the effects of T.

Overall, the reduction in total and specific inputs to GnRH neurons that we found in female sheep after prenatal T suggests a profound blunting of the inherent neural plasticity within the GnRH system. This is entirely consistent with previous observations in sheep that females have greater numbers of synaptic inputs to GnRH neurons than males (14). Thus, under the default reproductive neuroendocrine condition (i.e. female), GnRH neurons possess greater numbers of neuronal inputs that then require active removal in the male, although the mechanisms involved remain to be identified. We propose that most of this “fine tuning” occurs after the critical period of sexual differentiation, because virtually all of the changes found in the current study were first observed at GD140 or later.

The disruptions of both of seasonal ovarian cyclicity (10, 46) and reproductive lifespan (10, 47) are associated with disruption of GnRH neurocircuitry induced by prenatal T. One interpretation of these results is that prenatal T accelerated reproductive aging, a process similar to that found in sheep subject to intense domestication and selection (48, 49). However, it should be cautioned that neither our current study nor previous studies included aged CONT females in which reproductive senescence occurred naturally. Sheep are relatively long-lived species with reproductive activity normally ceasing between six and 20 yr of age, depending on the breed (48, 50–52). In the context of the present study, prenatal T-treated females reached puberty (ovarian cycle onset) at the same age as CONT females (10, 12, 47) but not earlier. Thus, we conclude that the early cessation of reproductive activity observed in the adult T females was programmed in utero by T and occurred independently of the timing of puberty.

A natural extension of the aforementioned interpretation of T's role in determining reproductive lifespan is that this was mediated by programming actions on GnRH neurocircuitry and, to some extent, also on glial cells. Nevertheless, the precise neural targets still remain to be determined. GABAergic neurons are located in various brain regions that serve as putative sources of GnRH afferents (53, 54), and some are known to bind both estrogens and androgens (55). Relevant to the presenting findings, estrogen receptor α is expressed by glutamatergic (VGLUT2) neurons (56). Therefore, because we saw a reduction in numbers of VGLUT2 and total numbers of inputs to GnRH neurons in older T females, this in part may explain the loss of positive feedback signaling in these females and one that may have begun even earlier. Interestingly, some changes in GnRH afferents were apparent in 10-month-old females when all were cycling normally, suggesting that some degree of compensatory change can overcome this reduction to maintain ovarian cyclicity. This could also by interpreted to indicate that the anatomical changes observed precede the ovarian dysfunction seen in the 21-month-old females. Given the extensive distribution of estrogen receptor α neurons that provide potential inputs to GnRH neurons in the female sheep (57), it seems likely that a potentially large number of brain regions are programmed during fetal life to cause adult endocrinopathies.

It is unlikely that the changes in GnRH inputs that we documented were the result of changes in numbers of estrogen receptor α containing neurons per se, because these do not change in response to prenatal androgen exposure in sheep (58). Thus, changes in GnRH afferents originating from these neurons must reflect either changes related to neural activity, to glial involvement, or both. Evidence supporting the former has recently been provided for somatostatin neurons containing estrogen receptors in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (59). Given that reductions in glial ensheathment and numbers of GnRH inputs paralleled each other, we favor the interpretation that both play integral roles in determining adult neuroendocrine phenotype. Together with our earlier work comparing seasonal changes in GnRH inputs and glial associations (17) and work in rodents (60), it is evident that glial cells are intimately involved in long-term neuronal plasticity on several different time scales.

In summary, the results of the present study reveal that GnRH afferents in the female sheep normally increase with prenatal age and that this change continues into adulthood. Under the influence of T, GnRH neurocircuitry and glial associations are reprogrammed, resulting in a neuroendocrine phenotype that is unable to sustain reproductive activity into adulthood. Together, these findings support the hypothesis that GnRH neurocircuitry is subject to programming in utero.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 HD044232.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- CONT

- Control

- DHT

- dihydrotestosterone

- GABA

- γ-aminobutyric acid

- GD

- gestational day

- GFAP

- glial fibrillary acidic protein

- ir

- immunoreactive

- PB

- phosphate buffer

- Syn-I

- Synapsin-I

- T

- testosterone treatment

- VGAT

- vesicular GABA transporter

- VGLUT2

- vesicular glutamate transporter 2.

References

- 1. Gorski RA. 1978. Sexual differentiation of the brain. Hosp Pract 13:55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Short RV. 1979. Sex determination and differentiation. Br Med Bull 35:121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Foster DL, Jackson LM, Padmanabhan V. 2007. Novel concepts about normal sexual differentiation of reproductive neuroendocrine function and the developmental origins of female reproductive dysfunction: the sheep model. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl 64:83–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Foecking EM, McDevitt MA, Acosta-Martínez M, Horton TH, Levine JE. 2008. Neuroendocrine consequences of androgen excess in female rodents. Horm Behav 53:673–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Resko JA, Roselli CE. 1997. Prenatal hormones organize sex differences of the neuroendocrine reproductive system: observations on guinea pigs and nonhuman primates. Cell Mol Neurobiol 17:627–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abbott DH, Dumesic DA, Levine JE, Dunaif A, Padmanabhan V. 2006. Animals models and fetal programming of PCOS. In: Azziz R, Nestler EJ, Dewailly D. eds. Contemporary endocrinology: androgen excess disorders in women: polycystic ovary syndrome and other disorders. 2nd ed Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, Inc.; 259–272 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Steiner RA, Clifton DK, Spies HG, Resko JA. 1976. Sexual differentiation and feedback control of luteinizing hormone secretion in the rhesus monkey. Biol Reprod 15:206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Simerly RB. 2002. Wired for reproduction: organization and development of sexually dimorphic circuits in the mammalian forebrain. Annu Rev Neurosci 25:507–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCarthy MM, Wright CL, Schwarz JM. 2009. New tricks by an old dogma: mechanisms of the organizational/activational hypothesis of steroid-mediated sexual differentiation of brain and behavior. Horm Behav 55:655–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Birch RA, Padmanabhan V, Foster DL, Unsworth WP, Robinson JE. 2003. Prenatal programming of reproductive neuroendocrine function: fetal androgen exposure produces progressive disruption of reproductive cycles in sheep. Endocrinology 144:1426–1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Herbosa CG, Dahl GE, Evans NP, Pelt J, Wood RI, Foster DL. 1996. Sexual differentiation of the surge mode of gonadotropin secretion: prenatal androgens abolish the gonadotropin-releasing hormone surge in the sheep. J Neuroendocrinol 8:627–633 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sharma TP, Herkimer C, West C, Ye W, Birch R, Robinson JE, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V. 2002. Fetal programming: prenatal androgen disrupts positive feedback actions of estradiol but does not affect timing of puberty in female sheep. Biol Reprod 66:924–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barker DJ. 1990. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ 301:1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim SJ, Foster DL, Wood RI. 1999. Prenatal testosterone masculinizes synaptic input to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in sheep. Biol Reprod 61:599–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foster DL, Padmanabhan V, Wood RI, Robinson JE. 2002. Sexual differentiation of the neuroendocrine control of gonadotrophin secretion: concepts derived from sheep models. Reprod Suppl 59:83–99 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jackson LM, Timmer KM, Foster DL. 2009. Organizational actions of postnatal estradiol in female sheep treated prenatally with testosterone: programming of prepubertal neuroendocrine function and the onset of puberty. Endocrinology 150:2317–2324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jansen HT, Cutter C, Hardy S, Lehman MN, Goodman RL. 2003. Seasonal plasticity within the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) system of the ewe: changes in identified GnRH inputs and glial association. Endocrinology 144:3663–3676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sergeeva A, Jansen HT. 2009. Neuroanatomical plasticity in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone system of the ewe: seasonal variation in glutamatergic and γ-aminobutyric acidergic afferents. J Comp Neurol 515:615–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xiong JJ, Karsch FJ, Lehman MN. 1997. Evidence for seasonal plasticity in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) system of the ewe: changes in synaptic inputs onto GnRH neurons. Endocrinology 138:1240–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barrell GK, Moenter SM, Caraty A, Karsch FJ. 1992. Seasonal changes of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion in the ewe. Biol Reprod 46:1130–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brooks AN, Currie IS, Gibson F, Thomas GB. 1992. Neuroendocrine regulation of sheep fetuses. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 45:69–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Caldani M, Antoine M, Batailler M, Duittoz A. 1995. Ontogeny of GnRH systems. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 49:147–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matwijiw I, Thliveris JA, Faiman C. 1989. Hypothalamo-pituitary portal development in the ovine fetus. Biol Reprod 40:1127–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Polkowska J, Dubois MP, Jutisz M. 1987. Maturation of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) and somatostatin (SRIF) neuronal systems in the hypothalamus of growing ewe lambs. Reprod Nutr Dev 27:627–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Polkowska J. 1986. Ontogeny of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) and somatostatin (SRIF) in the hypothalamus of the sheep. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 24:195–201 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Manikkam M, Crespi EJ, Doop DD, Herkimer C, Lee JS, Yu S, Brown MB, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V. 2004. Fetal programming: prenatal testosterone excess leads to fetal growth retardation and postnatal catch-up growth in sheep. Endocrinology 145:790–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Veiga-Lopez A, Steckler TL, Abbott DH, Welch KB, MohanKumar PS, Phillips DJ, Refsal K, Padmanabhan V. 2011. Developmental programming: impact of excess prenatal testosterone on intrauterine fetal endocrine milieu and growth in sheep. Biol Reprod 84:87–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Manikkam M, Steckler TL, Welch KB, Inskeep EK, Padmanabhan V. 2006. Fetal programming: prenatal testosterone treatment leads to follicular persistence/luteal defects; partial restoration of ovarian function by cyclic progesterone treatment. Endocrinology 147:1997–2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sternberg SR. 1983. Biomedical image processing. Computer 16:22–34 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Veiga-Lopez A, Ye W, Phillips DJ, Herkimer C, Knight PG, Padmanabhan V. 2008. Developmental programming: deficits in reproductive hormone dynamics and ovulatory outcomes in prenatal, testosterone-treated sheep. Biol Reprod 78:636–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jansen HT, Hileman SM, Lubbers LS, Kuehl DE, Jackson GL, Lehman MN. 1997. Identification and distribution of neuroendocrine gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the ewe. Biol Reprod 56:655–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lehman MN, Robinson JE, Karsch FJ, Silverman AJ. 1986. Immunocytochemical localization of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) pathways in the sheep brain during anestrus and mid-luteal phase of the estrous cycle. J Comp Neurol 244:19–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Minelli A, Alonso-Nanclares L, Edwards RH, DeFelipe J, Conti F. 2003. Postnatal development of the vesicular GABA transporter in rat cerebral cortex. Neuroscience 117:337–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakamura K, Hioki H, Fujiyama F, Kaneko T. 2005. Postnatal changes of vesicular glutamate transporter (VGluT)1 and VGluT2 immunoreactivities and their colocalization in the mouse forebrain. J Comp Neurol 492:263–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roselli CE, Resko JA, Stormshak F. 2003. Estrogen synthesis in fetal sheep brain: effect of maternal treatment with an aromatase inhibitor. Biol Reprod 68:370–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Veiga-Lopez A, Astapova OI, Aizenberg EF, Lee JS, Padmanabhan V. 2009. Developmental programming: contribution of prenatal androgen and estrogen to estradiol feedback systems and periovulatory hormonal dynamics in sheep. Biol Reprod 80:718–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wood RI, Foster DL. 1998. Sexual differentiation of reproductive neuroendocrine function in sheep. Rev Reprod 3:130–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gluckman PD, Marti-Henneberg C, Kaplan SL, Grumbach MM. 1983. Hormone ontogeny in the ovine fetus: XIV. The effect of 17β-estradiol infusion on fetal plasma gonadotropins and prolactin and the maturation of sex steroid-dependent negative feedback. Endocrinology 112:1618–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gao XB, van den Pol AN. 2001. GABA, not glutamate, a primary transmitter driving action potentials in developing hypothalamic neurons. J Neurophysiol 85:425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sullivan SD, Moenter SM. 2005. GABAergic integration of progesterone and androgen feedback to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Biol Reprod 72:33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sullivan SD, Moenter SM. 2004. Prenatal androgens alter GABAergic drive to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons: implications for a common fertility disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:7129–7134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sim JA, Skynner MJ, Pape JR, Herbison AE. 2000. Late postnatal reorganization of GABA(A) receptor signalling in native GnRH neurons. Eur J Neurosci 12:3497–3504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sullivan SD, DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. 2003. Metabolic regulation of fertility through presynaptic and postsynaptic signaling to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Neurosci 23:8578–8585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tomaszewska-Zaremba D, Przekop F. 2006. The role of GABA(A) and GABA(B) receptors in the control of GnRH release in anestrous ewes. Reprod Biol 6(Suppl 2):3–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ganguly K, Schinder AF, Wong ST, Poo M. 2001. GABA itself promotes the developmental switch of neuronal GABAergic responses from excitation to inhibition. Cell 105:521–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Clarke IJ. 1977. The sexual behaviour of prenatally androgenized ewes observed in the field. J Reprod Fertil 49:311–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Robinson JE, Birch RA, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V. 2002. Prenatal exposure of the ovine fetus to androgens sexually differentiates the steroid feedback mechanisms that control gonadotropin releasing hormone secretion and disrupts ovarian cycles. Arch Sex Behav 31:35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mysterud A, Steinheim G, Yoccoz NG, Holand O, Stenseth NC. 2002. Early onset of reproductive senescence in domestic sheep, Ovis aries. Oikos 97:177–183 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hamilton WD. 1966. The moulding of senescence by natural selection. J Theor Biol 12:12–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gonzalez-Bulnes A, Souza CJ, Campbell BK, Baird DT. 2004. Effect of ageing on hormone secretion and follicular dynamics in sheep with and without the Booroola gene. Endocrinology 145:2858–2864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Doney JM, Ryder ML, Gunn RG, Grubb P. 1974. Colour, conformation, affinties, fleece and patterns of inheritance of the Soay sheep. In: Jewell PA, Milner C, Boyd JM. eds. Island survivors: the ecology of the Soay sheep of St Kilda. London: The Athelone Press; 88–125 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Berube CH, Festa-Bianchet M, Jorgenson JT. 1999. Individual differences, longevity, and reproductive senescence in bighorn ewes. Ecology 80:2555–2565 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Maffucci JA, Gore AC. 2009. Chapter 2: hypothalamic neural systems controlling the female reproductive life cycle gonadotropin-releasing hormone, glutamate, and GABA. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 274:69–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moenter SM, Chu Z, Christian CA. 2009. Neurobiological mechanisms underlying oestradiol negative and positive feedback regulation of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone neurones. J Neuroendocrinol 21:327–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Herbison AE. 1995. Neurochemical identity of neurones expressing oestrogen and androgen receptors in sheep hypothalamus. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 49:271–283 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Eyigor O, Lin W, Jennes L. 2004. Identification of neurones in the female rat hypothalamus that express oestrogen receptor-α and vesicular glutamate transporter-2. J Neuroendocrinol 16:26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Goubillon M, Delaleu B, Tillet Y, Caraty A, Herbison AE. 1999. Localization of estrogen-receptive neurons projecting to the GnRH neuron-containing rostral preoptic area of the ewe. Neuroendocrinology 70:228–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gorton LM, Mahoney MM, Magorien JE, Lee TM, Wood RI. 2009. Estrogen receptor immunoreactivity in late-gestation fetal lambs. Biol Reprod 80:1152–1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Robinson JE, Grindrod J, Jeurissen S, Taylor JA, Unsworth WP. 2010. Prenatal exposure of the ovine fetus to androgens reduces the proportion of neurons in the ventromedial and arcuate nucleus that are activated by short-term exposure to estrogen. Biol Reprod 82:163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Garcia-Segura LM, McCarthy MM. 2004. Minireview: role of glia in neuroendocrine function. Endocrinology 145:1082–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.