Abstract

Cells are known to take up molecules through membrane transport mechanisms such as active transport, channels, and facilitated transport. We report here a new membrane transport mechanism that employs neither cellular energy like active transport nor a preexisting electrochemical gradient of the free substrate like channels or facilitated transport. Through this mechanism, cells take up vitamin A bound with high affinity to retinol binding protein (RBP) in the blood. This mechanism is mediated by the RBP receptor STRA6, which defines a new type of cell-surface receptor. STRA6 is essential for the proper functioning of multiple human organs, but the mechanisms that enable and control its cellular vitamin A uptake activity are unknown. We found that STRA6-mediated vitamin A uptake is tightly coupled to specific intracellular retinoid storage proteins, but no single intracellular protein is absolutely required for its transport activity. By developing sensitive real-time monitoring techniques, we found that STRA6 is not only a membrane receptor but also catalyzes vitamin A release from RBP. However, vitamin A released from RBP by STRA6 inhibits further vitamin A release by STRA6 unless specific intracellular retinoid storage proteins relieve this inhibition. This mechanism is responsible for its coupling to intracellular storage proteins. The coupling of uptake to storage provides high specificity in cellular uptake of vitamin A and prevents the excessive accumulation of free vitamin A. We have also identified a robust small molecule-based technique to specifically stimulate cellular vitamin A uptake. This technique has implications in treating human diseases.

Vitamin A and its derivatives (retinoids) are a group of chemicals that perform critical and diverse biological functions. For example, the aldehyde form of vitamin A functions as the photoreceptor chromophore in vision (1–3) and regulates adipogenesis (4). The acid forms of vitamin A (retinoic acid) regulate gene transcription and control cell growth and differentiation (5, 6). Due to its potent biological activities, nonspecific and excessive vitamin A uptake can lead to severe toxicity (7–10). How cells control vitamin A uptake to prevent its excessive accumulation and random diffusion is unknown. Plasma retinol binding protein (RBP) is the principle carrier of vitamin A in the blood (11–13) and its excessive secretion plays a role in insulin resistance (14). STRA6, a membrane protein originally identified in cancer cells (15, 16), is the high-affinity RBP receptor that mediates cellular uptake of vitamin A (17). It is expressed in cells or tissues known to depend on vitamin A for proper function. For example, its expression in the brain is consistent with known neuronal functions of vitamin A derivatives (18, 19). Both human and animal studies have shown that loss of STRA6 can lead to severe defects in multiple organs (20, 21).

STRA6 is a multi-transmembrane domain protein that represents a new type of cell-surface receptor. STRA6’s mechanism does not depend on endocytosis (17). Its energy-independence also excludes primary or secondary active transport. Unlike channels or facilitated transporters, which are driven by the electrochemical gradient of the free substrate, STRA6’s substrate retinol is not free, has no charge, and can only be provided one molecule at a time by RBP. Its mechanism is further complicated by the high affinity interaction between retinol and RBP, its dependence on both RBP binding to deliver retinol and RBP dissociation for the next RBP to bind, and the involvement of intracellular proteins. How STRA6 mediates substrate uptake is unknown and its activity cannot be explained by known cellular uptake mechanisms (Figure 1A). We (17) and other investigators (21, 22) found that lecithin retinol acyltransferase (LRAT) stimulates STRA6’s vitamin A (retinol) uptake activity. It was also found that STRA6 and LRAT cannot take up retinylamine from the retinylamine/RBP complex (22) or retinoic acid from the retinoic acid/RBP complex (21). Why does LRAT stimulate STRA6’s retinol uptake, but not the uptake of other retinoids? Does STRA6 have any retinol uptake activity without LRAT? If it does, why can LRAT stimulate its activity? If it does not, is STRA6 only a receptor for RBP? How does STRA6 allow retinol to enter a cell while leaving RBP outside a cell? Is LRAT the only protein that can stimulate STRA6’s activity? LRAT converts retinol to retinyl ester, a storage form of vitamin A. Retinol can also be stored by binding to cellular retinol binding proteins (CRBP), such as CRBP-I (23–25) and CRBP-II (26). Can CRBP-I or CRBP-II stimulate STRA6’s retinol uptake? Is retinol the only substrate that can be taken up through STRA6? STRA6 was also found to facilitate the loading of exogenous retinol into apo-RBP in the presence of LRAT (21). Does LRAT stimulate retinol loading or retinol uptake? Can a small molecule stimulate STRA6’s retinol uptake? Answers to these questions might help to reveal STRA6’s vitamin A uptake mechanism.

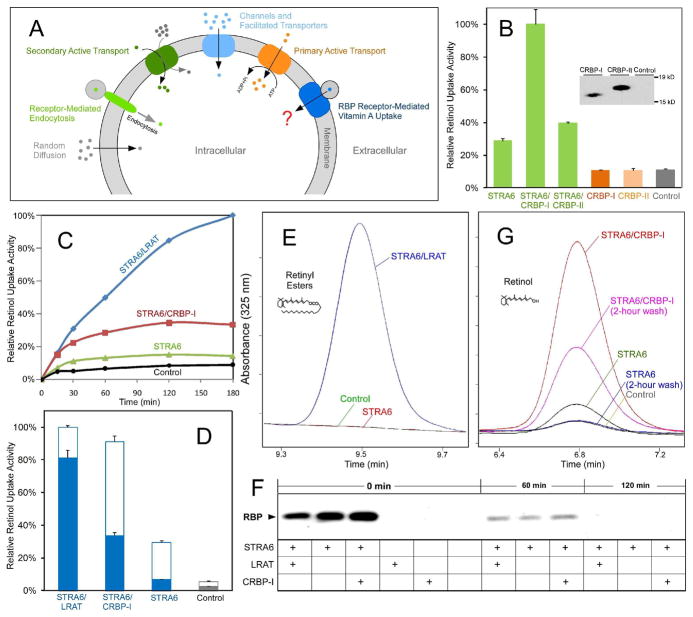

Figure 1.

STRA6 couples cellular vitamin A uptake to intracellular storage. (A) Schematic diagram comparing known cellular uptake mechanisms (e.g., receptor-mediated endocytosis, primary and secondary active transport, channels, facilitated transport, and random diffusion) and RBP receptor-mediated cellular vitamin A uptake. (B) CRBP-I is much more effective than CRBP-II in coupling with STRA6 to take up 3H-retinol from 3H-retinol/RBP. Both CRBP-I and CRBP-II were tagged with 6X His tag at the C-terminus and their expression in transfected cells was detected with anti-His tag antibody to compare their expression levels. (C) Comparison of the time-dependent accumulation of 3H-retinol for STRA6/LRAT, STRA6/CRBP-I, STRA6 only cells, and control untransfected cells after uptake from 3H-retinol/RBP. The highest 3H-retinol uptake activity of STRA6/LRAT cells is defined as 100%. (D) Removal of cell surface bound 3H-retinol/RBP by excessive unlabeled holo-RBP after 3H-retinol uptake from 3H-retinol-RBP. Unlike STRA6/LRAT cells, most 3H-retinol associated with STRA6 cells (signal above the background of untransfected cells) represents 3H-retinol/RBP bound to the cell surface. Unfilled columns represent cell surface-bound 3H-retinol in the form of 3H-retinol/RBP. Filled columns represent cellular 3H-retinol uptake. (E) HPLC analysis of retinyl ester formation by STRA6/LRAT cells, STRA6-only cells, and control untransfected cells using human serum as the source of holo-RBP. Peaks representing retinyl esters are shown. Given the role of LRAT in retinyl ester formation, STRA6-only and control cells have no detectable retinyl esters. (F) Analysis of the dissociation of RBP bound to cells transfected with STRA6, STRA6/LRAT, STRA6/CRBP-I and control cells. After cells were incubated with holo-RBP for one hour, unbound RBP was removed by washing cells with PBS. After further incubation in serum free media (SFM) for 0, 60, or 120 minutes, RBP associated with cells was analyzed by Western blot. RBP completely dissociated from STRA6 after two hours of incubation in SFM. (G) HPLC analysis of retinol uptake from human serum by cells transfected by STRA6/CRBP-I, STRA6, and control cells. Two hours of incubation in SFM removed cell surface bound RBP. Peaks representing retinol are shown. One unit on the Y axis represents 1 mAU for E and G.

RESULTS

The coupling of STRA6-mediated vitamin A uptake to CRBP-I and LRAT

We tested whether CRBP-I or CRBP-II can enhance STRA6’s vitamin A uptake and found that CRBP-I does enhance STRA6’s vitamin A uptake activity (Supplemental Figure 1). In contrast, CRBP-II is much less effective although they have similar expression levels (Figure 1B). This difference between CRBP-I and CRBP-II suggests that the ability to bind retinol is not sufficient to enhance STRA6’s vitamin A uptake. Using a 3H-retinol uptake assay, we next compared the time course of vitamin A uptake between cells expressing STRA6/LRAT, STRA6/CRBP-I and STRA6 alone and found that STRA6/CRBP-I and STRA6 cells, but not STRA6/LRAT cells, exhibit obvious saturation (Figure 1C). Although this result suggests saturation of available apo-CRBP for the CRBP-I reaction and ongoing synthesis of retinyl esters for the STRA6/LRAT reaction, the nature of vitamin A uptake by STRA6-only cells is not clear.

To overcome the complication of retinol associated with cells in the form of surface-bound holo-RBP, we added a large excess of unlabeled holo-RBP to compete with 3H-retinol/RBP bound to STRA6 on the cell surface. Surprisingly, STRA6 has little “true” retinol uptake activity after cell-surface holo-RBP is removed (Figure 1D). Since holo-RBP exists in the serum in the form of holo-RBP/transthyretin (TTR) complex (12), we also used an HPLC assay and human serum as the source of holo-RBP to confirm the finding that STRA6 by itself takes up little retinol (Figures 1E, 1F and 1G). Due to LRAT’s role in retinyl ester formation (Figure 1E), retinol-based analysis (Figure 1G) is necessary to reveal the nature of retinol uptake activity of STRA6-only cells. STRA6-only cells take up even less vitamin A in the presence of TTR, which partially inhibits STRA6’s activity (Supplemental Figure 2). The dependence of STRA6 on LRAT or CRBP-I for vitamin A uptake suggests that STRA6 is tightly coupled to these proteins.

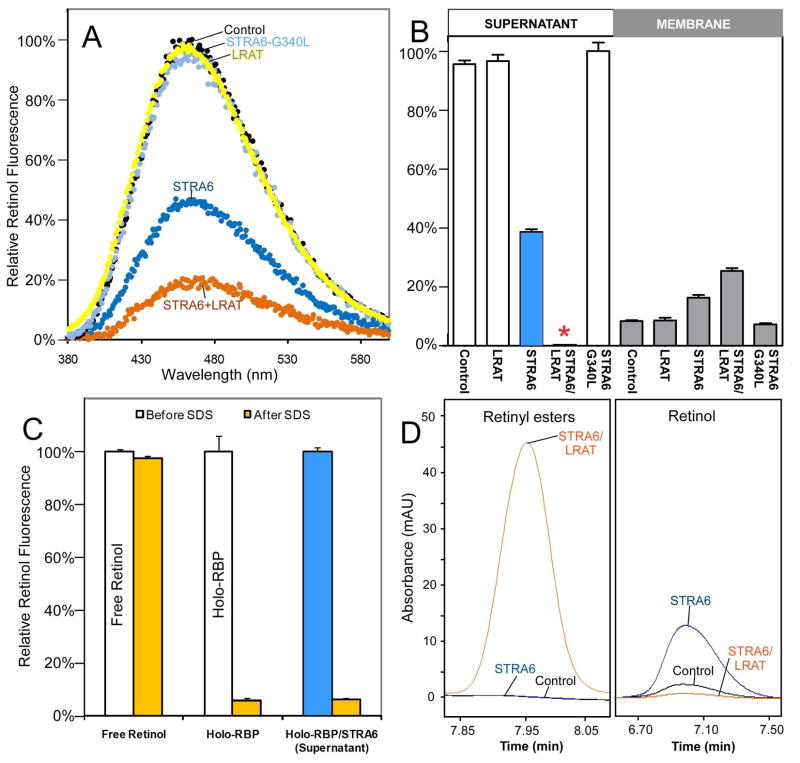

STRA6-catalyzed retinol release activity and its inhibition by free retinal

The very low vitamin A uptake activity of STRA6-only cells suggests that STRA6 alone is seemingly ineffective in releasing retinol from holo-RBP. If retinol is not released from RBP and RBP does not get endocytosed, how does retinol enter its target cell? To resolve this paradox, we tested whether STRA6 accelerates retinol release by developing a sensitive assay for retinol release from holo-RBP. This assay is based on the dramatic enhancement of retinol fluorescence when retinol is bound to RBP. In this assay, STRA6/LRAT membranes cause a large reduction of retinol fluorescence when incubated with holo-RBP. Interestingly, STRA6 membranes also cause a significant reduction in retinol fluorescence, while membranes from control, LRAT and a STRA6 mutant (27) that has normal cell surface expression but does not bind RBP fail to cause any reduction (Figure 2A). We further fractionated the reactions into membrane and supernatant fractions and found that STRA6/LRAT causes complete retinol release from RBP in the supernatant while STRA6 causes partial retinol release (Figures 2B). Retinol in the supernatant of STRA6-treated reaction is present in the form of holo-RBP not as free retinol (Figure 2C). As expected, retinol in STRA6/LRAT membrane has been converted to retinyl esters, but retinol in STRA6 membrane remains the retinol form (Figure 2D). We also purified the RBP/TTR complex from human serum and demonstrated that STRA6 catalyzes retinol release from the RBP/TTR complex as well (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 2.

STRA6-catalyzed retinol release from holo-RBP. (A) Retinol fluorescence emission spectra of holo-RBP incubated with membranes from STRA6, STRA6/LRAT, STRA6-G340L mutant, or control cells. The maximum emission signal of the control is defined as 100%. (B) Comparison of STRA6 and STRA6/LRAT in retinol release from holo-RBP. After holo-RBP was incubated with STRA6, STRA6/LRAT, STRA6-G340L, or control untransfected membranes for two hours, each reaction was fractionated into membrane bound and soluble fractions. The retinol fluorescence of each fraction was measured. The highest retinol fluorescence signal (the unbound fraction of G340L) is defined as 100%. Although there is no detectable retinol in the supernatant of STRA6/LRAT treated holo-RBP (red asterisk), there is significant retinol fluorescence in the supernatant of STRA6-treated holo-RBP (blue bar). (C) Since treatment with SDS (0.2%) suppresses the fluorescence of holo-RBP but not free retinol, the suppression of retinol fluorescence of the supernatant of STRA6-treated holo-RBP suggests that retinol is present in the form of holo-RBP not in the free form. The retinol fluorescence of each sample before SDS treatment is defined as 100%. (D) The fates of retinol released into membranes from holo-RBP by STRA6 and STRA6/LRAT were analyzed by HPLC. Retinol in STRA6/LRAT membrane has been converted to retinyl esters, but retinol in STRA6 membrane remains the retinol form.

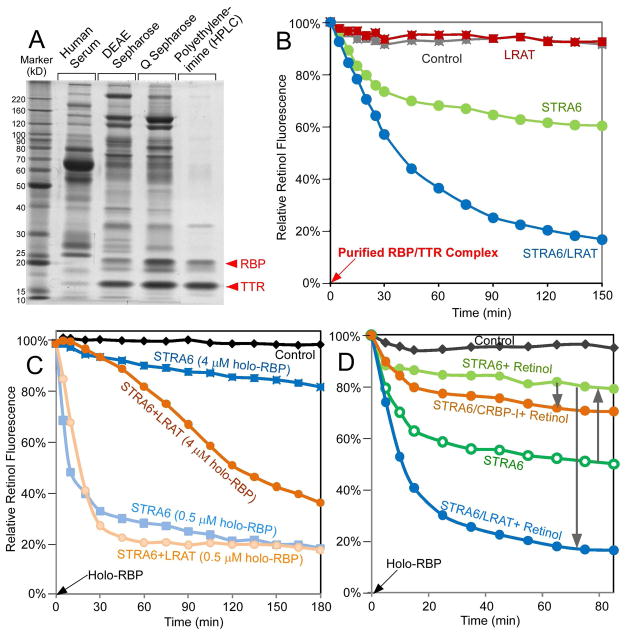

Figure 3.

Characterization of STRA6-catalyzed retinol release. (A) Purification of the RBP/TTR complex from the human serum. Normal human serum and the peak fractions containing RBP/TTR from the three columns used to purify the RBP/TTR complex are shown on the left in the Sypro Ruby-stained SDS-PAGE gel. (B) STRA6 catalyzes retinol release from the native RBP/TTR complex. Incubation of the purified RBP/TTR complex (0.4 μM) with STRA6 or STRA6/LRAT membranes but not control or LRAT membranes led to significant decrease in retinol fluorescence. Retinol fluorescence at 0 min is defined as 100%. (C) Retinol fluorescence assay (holo-RBP was added at 0 min) showing that STRA6 (0.2 μM) released retinol as effectively as STRA6 with LRAT when the RBP to STRA6 molar ratio was low but much less effectively when the RBP to STRA6 molar ratio was increased. Retinol fluorescence signal of each time point of each reaction is normalized to its own value at 0 min (defined as 100%). (D) Free retinol (4 μM) inhibited STRA6-catalyzed retinol release from holo-RBP (1 μM) (upwards arrow), but this inhibition was relieved by LRAT or CRBP-I (downwards arrow). Retinol fluorescence at 0 min is defined as 100%.

Why does STRA6 stimulate retinol release in the fluorescence assay but cause little vitamin A uptake in cellular retinol uptake assays? This result can be explained by the ratio of holo-RBP to STRA6 used in these assays. The retinol fluorescence assays have much lower holo-RBP to STRA6 ratios and much higher STRA6 concentrations compared with those used in the cellular retinol uptake assay. In the fluorescence assays, STRA6 becomes more dependent on LRAT for retinol release when the holo-RBP to STRA6 ratio is increased (Figure 3C). This is also confirmed in vitamin A uptake assays in live cells (Supplemental Figure 3). One hypothesis to explain STRA6’s dependence on LRAT is that retinol released by STRA6 inhibits further retinol release, but LRAT relieves the inhibition by converting retinol to retinyl esters. To test this hypothesis, we added free retinol to STRA6 membrane and indeed observed a strong inhibitory effect on STRA6-catalyzed retinol release (Figure 3D). This inhibitory effect can be relieved by LRAT or CRBP-I.

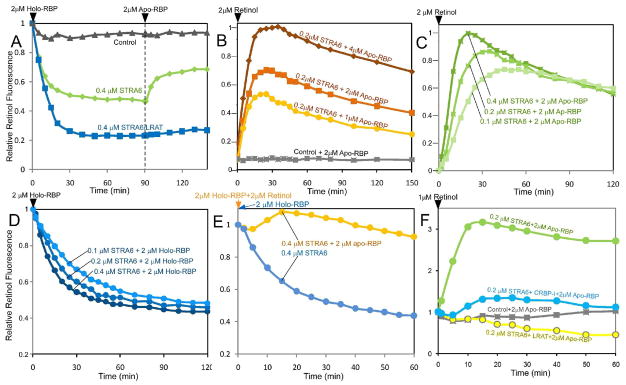

STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading activity and its biphasic kinetics

If STRA6 depends more on LRAT for retinol release when there is more holo-RBP, what is the effect of more apo-RBP? We tested the addition of apo-RBP to STRA6 after it has catalyzed the release of retinol from holo-RBP and found that the addition of apo-RBP caused a fluorescence increase in the STRA6 reaction but not in the STRA6/LRAT reaction (Figure 4A). The increase in fluorescence suggests that retinol released by STRA6 was loaded back to RBP and that LRAT’s conversion of retinol into retinyl ester prevented the loading. Since this experiment cannot distinguish whether retinol loading started from free retinol or a retinol/STRA6 complex, we tested free retinol and found that STRA6 catalyzes very efficient loading of free retinol into RBP (Figure 4B). The initial phase of STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading is very different from the initial phase of STRA6-catalyzed retinol release (Figures 4C and 4D). In contrast to the fluorescence decay during retinol release, which does not show a downward peak, the STRA6-catalyzed fluorescence increase is characterized by a peak (Figures 4B and 4C). This biphasic property of the loading reaction can be explained by the dual functions of STRA6 in first catalyzing retinol loading and then catalyzing retinol release of the newly formed holo-RBP. Intriguingly, when STRA6 is presented with equal opportunities to catalyze retinol release or to catalyze retinol loading, the loading activity predominates initially (Figure 4E). The robust retinol loading activity of STRA6 suggests the possibility that STRA6 depends more on LRAT for retinol release when there is more holo-RBP because the released retinol inhibits further release due to the STRA6’s retinol loading activity. Consistently, STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading is inhibited by LRAT and CRBP-I (Figure 4F). STRA6’s retinol loading activity is also confirmed by HPLC analysis (Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Retinol fluorescence assays to monitor STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading in real time. Retinol or RBP added at 0 min at the start of each reaction is indicated at the lower left corner of each graph. (A) Retinol released from RBP after incubating with STRA6 was loaded back to RBP if apo-RBP was added. LRAT blocked this loading activity. Holo-RBP was added at 0 min and apo-RBP was added at 90 min for all reactions. Retinol fluorescence at 0 min is defined as 100%. (B) STRA6 catalyzed the rapid loading of free retinol to apo-RBP, but after about 30 minutes, the signals started to decay. No detectable retinol loading happened with the control membrane. Retinol was added at 0 min. The highest retinol fluorescence value reached during retinol loading is defined as 100%. (C) and (D) Comparison of STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading (C) and retinol release (D). Other than the three different STRA6 concentrations, the reactions contained identical amounts of retinol (2 μM, either free or bound to RBP) and RBP (2 μM, either as apo-RBP or holo-RBP). The fluorescence of each loading reaction is characterized by a rapid rise to a peak followed by decay. In contrast, the fluorescence of each release reaction is characterized by slower decrease to a plateau. For the loading reaction, the highest retinol fluorescence in all reactions is defined as 1. For the release reaction, retinol fluorescence at 0 min is defined as 1. (E) When STRA6 was presented with equal opportunities to catalyze either retinol release (2 μM retinol and 2 μM apo-RBP) or loading (2 μM holo-RBP), the loading activity dominated initially (orange line). A reaction of STRA6-catalyzed retinol release is shown for comparison (blue line). Retinol fluorescence in the form of holo-RBP and or free retinol added at 0 min is defined as 1. (F) STRA6-dependent reloading of apo-RBP using free retinol is inhibited by both LRAT and CRBP-I. At 0 min, 1 μM of retinol was added to STRA6, STRA6/CRBP-I, STRA6/LRAT, or control membrane premixed with apo-RBP. CRBP-I concentration was 2 μM. The retinol fluorescence signal at 0 min is defined as 1.

Properties of CRBP-I responsible for its ability to couple to STRA6

CRBP-I and RBP are both retinol binding proteins. What’s the difference between STRA6-catalyzed loading of RBP versus STRA6-catalyzed loading of CRBP-I? CRBP-I and CRBP-II are also both retinol binding proteins. Why can only CRBP-I effectively couple to STRA6 to mediate vitamin A uptake from holo-RBP? To answer these questions, we developed a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) technique to monitor retinol transport to CRBP-I in real time. This technique is based on the significant overlap between the emission spectrum of retinol and the excitation spectrum of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) (Supplemental Figure 5). Using a fusion protein between CRBP-I and EGFP (EGFP-CRBP-I), we observed clear FRET signals between retinol and EGFP during STRA6-mediated retinol transfer from holo-RBP to EGFP-CRBP-I (Figures 5A and 5B). Real-time monitoring revealed an increase and saturation of FRET signals dependent on STRA6, time, and CRBP-I-concentrations; but no decay was observed unless apo-CRBP-I was added (Figure 5C and Supplemental Figure 6A). The stable signal suggests that STRA6-catalyzed retinol transfer to CRBP-I does not lead to further unloading of CRBP-I, in sharp contrast to the STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading of RBP (Figures 4B and 4C). Also in contrast to RBP, which depends on STRA6 for efficient loading with retinol (Figure 4B), CRBP-I absorbs retinol added to control membranes indistinguishably from STRA6 membranes (Supplemental Figure 6B) and is more effective in coupling to STRA6 than CRBP-II due to its higher affinity for retinol (Supplemental Figures 6C and 6D). These experiments suggest that CRBP-I’s high affinity binding to retinol distinguishes it from CRBP-II, and its STRA6-independent absorption of retinol from the membrane distinguishes it from RBP.

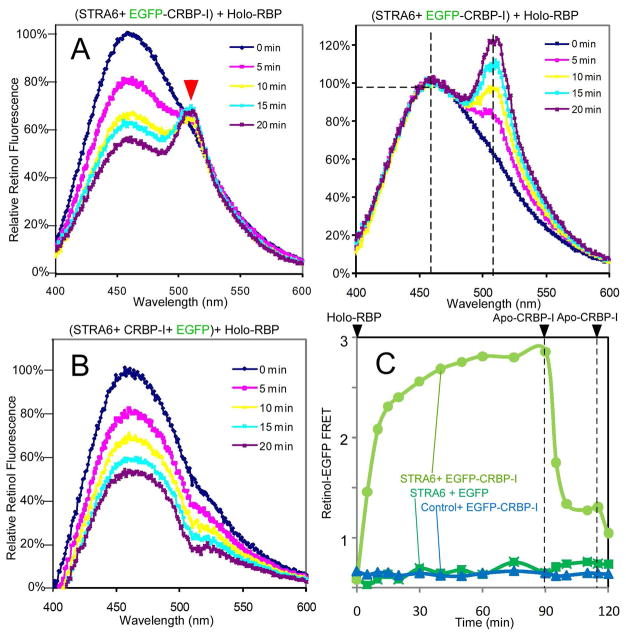

Figure 5.

Retinol-EGFP FRET assay to monitor STRA6-catalyzed transport of retinol from holo-RBP to EGFP-CRBP-I. For A and B, 0.5 μM holo-RBP was added at 0 min. (A) FRET between retinol and EGFP linked to CRBP-I is demonstrated by a time-dependent and concomitant increase in the EGFP emission peak at 510 nm (red arrowhead) and decrease in the retinol emission peak at 470 nm (left panel). Emission at 470 nm at 0 min is defined as 100%. The 510 nm peak becomes even more obvious after all spectra are normalized against the 470 nm peak (right panel). Emission at 470 nm is defined as 100%. (B) No 510 nm peak was observed if EGFP is not linked to CRBP-I. Emission at 470 nm at 0 min is defined as 100%. (C) Real-time FRET assays showing that FRET signals depended on both STRA6 and EGFP- CRBP-I and there was no decay of the signal unless apo-CRBP-I (1 μM) was added. Holo-RBP (2μM) was added at 0 min.

LRAT and CRBP-I independent stimulation of STRA6

Are LRAT and CRBP-I the only proteins that can couple to STRA6? LRAT and CRBP-I couple to STRA6 due to their ability to restrain the free substrate intermediate, which is inhibitory to retinol release. We tested whether other proteins that can interact with the free substrate couple to STRA6. Indeed, retinol dehydrogenase (RDH), which uses free retinol as the substrate, accelerates STRA6-catalyzed retinol release by converting retinol to retinal in the presence of NADP (Figure 6A). Cellular retinoic acid binding protein-I (CRABP-I), which binds free retinoic acid, couples to STRA6 in mediating retinoic acid uptake from the retinoic acid/RBP complex (Figure 6B). LRAT and CRBP-I, which don’t interact with retinoic acid, can no longer couple to STRA6 in this context (Figure 6B).

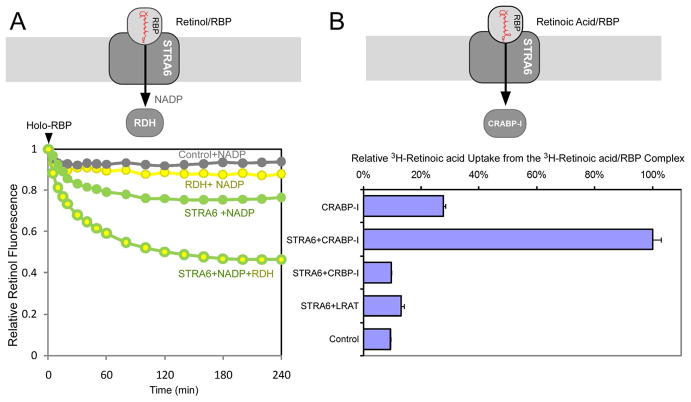

Figure 6.

LRAT and CRBP-I-independent enhancement of STRA6’s substrate uptake. Schematic diagram of each experiment is shown on the top. (A) Retinol fluorescence assay (4 μM holo-RBP added at 0 min) showing that RDH significantly enhanced STRA6-catalyzed retinol release. NADP (0.2 mM) was added to all reactions. (B) CRABP-I, but not CRBP-I or LRAT, couples with STRA6 for cellular 3H-retinoic acid uptake from 3H-retinoic acid/RBP. The activity of STRA6/CRABP-I transfected cell is defined as 100%. Activity in CRABP-I-only cells was due to non-specific release of retinoic acid from RBP into cells. The inability of CRBP-I and LRAT to couple to STRA6 in retinoic acid uptake is consistent with the facts that CRBP-I does not bind retinoic acid and retinoic acid is not a substrate for LRAT. A schematic diagram for each experiment is drawn on the top of each experiment.

β-ionone stimulates cellular vitamin A uptake in a STRA6-dependent manner

Can small molecules also enhance STRA6’s activity by affecting the free substrate intermediate? Free unlabeled retinol is expected to enhance 3H-retinol uptake from 3H-retinol/RBP if the unlabeled free retinol inhibits STRA6’s retinol loading activity by competing with 3H-retinol. We found that this is indeed the case (Figure 7A). As the natural substrate of RBP, retinol naturally inhibits STRA6-mediated vitamin A uptake and can only enhance STRA6’s uptake activity in the context of the 3H-retinol uptake assay. Is it possible that compounds similar to retinol can enhance STRA6’s activity in all assays? We tested β-ionone, a small chemical found in fruits and vegetables, which mimics retinol in structure but is not a retinoid. Indeed, β-ionone stimulates retinol uptake from holo-RBP in a dose-dependent manner in the 3H-retinol uptake assay (Figure 7A), the retinol fluorescence assay (Figures 7B and 7C), and the HPLC-based assay using human serum as the source of holo-RBP (Figure 7F). Like CRBP-I and LRAT, β-ionone stimulates STRA6’s vitamin A uptake activity by blocking STRA6’s retinol loading activity (Figures 7C and 7E). However, the exact mechanisms are different. CRBP-I and LRAT removes free retinol, but β-ionone competes with the free retinol in the STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading reaction (Figures 7D and 7E). Remarkably, as an exogenous small molecule, β-ionone can be as effective as CRBP-I in enhancing STRA6’s retinol uptake and can even further boost retinol uptake for STRA6/CRBP-I cells (Figure 7F).

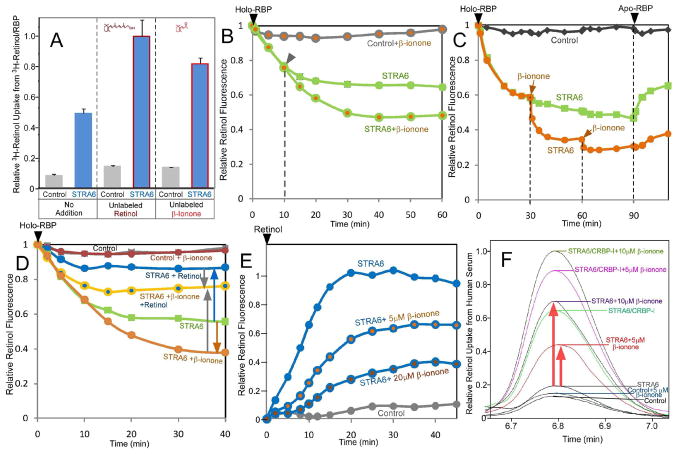

Figure 7.

β-ionone stimulates STRA6-mediated retinol uptake. (A) Unlabeled retinol or β-ionone accelerates STRA6-mediated uptake of 3H-retinol from 3H-retinol/RBP. Unlabeled retinol (2 μM) or β-ionone (2 μM) significantly boosted STRA6-mediated cellular uptake of 3H- retinol from 3H-retinol/RBP, but had little effect on the reactions with control cells. The specificity indicates that the effects of increased 3H-retinol uptake by both cold retinol and β-ionone are mediated by STRA6. (B) Retinol fluorescence assay (2 μM holo-RBP added at 0 min) showing that β-ionone (10 μM) promoted STRA6-catalyzed retinol release. β-ionone depends on STRA6 to accelerate RBP’s retinol release and there was no effect during the initial phase, as indicated by the arrowheads. (C) Holo-RBP (1 μM) was added at 0 min. β-ionone (10 μM) added at 30 min and 60 min accelerated retinol release. The effect is much more rapid compared to β-ionone added at 0 min (B). These results suggests that β-ionone only shows its stimulatory effect when there is a significant amount of retinol released by STRA6 and that β-ionone increases retinol release by blocking retinol loading. Consistently, STRA6 catalyzes retinol loading into apo-RBP (1 μg) added at 90 min in the absence of β-ionone but not in the presence of β-ionone. (D) β-ionone and retinol antagonize each other’s effect on retinol release by STRA6. Free retinol (2 μM) inhibited STRA6-catalyzed retinol release from holo-RBP (blue upwards arrow), but β-ionone (10 μM) enhanced STRA6 catalyzed retinol release (brown downwards arrow). Addition of β-ionone together with retinol led to less stimulatory effect than β-ionone alone (gray upwards arrow) and less inhibitory effect than retinol alone (gray downwards arrow). Holo-RBP (1 μM) was added at 0 min. (E) β-ionone inhibits STRA6-dependent retinol loading into apo-RBP in a concentration-dependent manner. Retinol (1 μM) was added at 0 min to each reaction containing 1 μM of apo-RBP. For B-E, the highest retinol fluorescence is defined as 1. (F) β-ionone enhanced STRA6-mediated retinol uptake from human serum for STRA6-only and STRA6/CRBP-I cells. The HPLC peaks for retinol after retinol extraction from each reaction are shown (red arrows highlight β-ionone’s stimulatory effect on STRA6). Cell surface bound RBP has been removed before this analysis. The highest retinol uptake activity is defined as 1.

A model of receptor-mediated vitamin A uptake

The diverse activities of STRA6 (Supplemental Figure 7 and Figure 8A), such as its abilities to catalyze retinol release, to couple to LRAT, to couple to CRBP-I, to couple to CRABP-I, to stimulate rapid retinol loading, and to enable β-ionone to greatly stimulate cellular retinol uptake, rule out alternative models of STRA6 uptake mechanism (Supplemental Figure 8) and lead to a unifying model (Figure 8B). In Step 1, STRA6 on the cell surface binds to holo-RBP with high-affinity. The source of the holo-RBP is the RBP/TTR complex in the blood. STRA6 effectively mediates vitamin A uptake from the holo-RBP/TTR complex (Figures 1E and 1G) although TTR partially suppresses STRA6’s activity (Supplemental Figure 2). In Step 2, STRA6 catalyzes retinol release from holo-RBP. STRA6’s ability to catalyze retinol release has been demonstrated and analyzed in real time (Figures 2, 3, 4A, 4D, 6A, and 7B–7D). In Step 3, the released retinol either inhibits further retinol release through the robust STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading activity (pathway 3a) or is removed by CRBP-I and LRAT (pathway 3c). STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading has been analyzed in real time (Figures 4A, 4B, 4C, 4E, 4F, and 7E). STRA6-mediated retinol uptake is coupled to CRBP-I and LRAT because they can restrain the inhibitory retinol intermediate and inhibit retinol loading. In the presence of β-ionone, pathway 3a is blocked, retinol uptake no longer depends on CRBP-I or LRAT (pathway 3b) (Figure 8B). In Step 4, apo-RBP dissociates from STRA6 and will be lost to kidney filtration due to its inability to bind TTR (12).

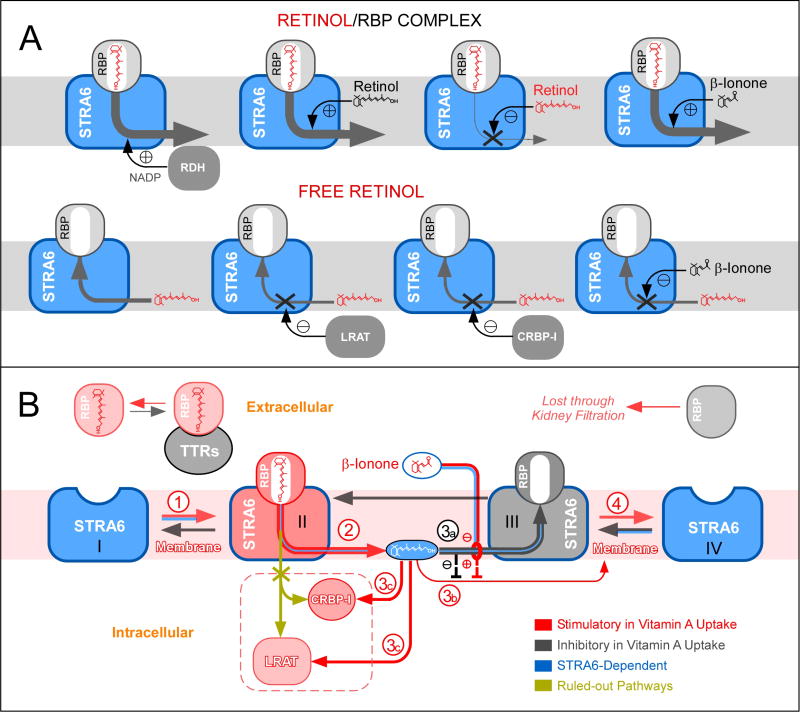

Figure 8.

Schematic diagrams of STRA6’s retinol release and retinol loading activities and its vitamin A uptake mechanism. (A) Upper figure: Free retinol can either enhance or suppress STRA6-mediated vitamin A uptake depending on the experimental design. For 3H-retinol uptake assay, additional free retinol (unlabeled) enhances 3H-retinol uptake. For assays designed to monitor unlabeled retinol such as retinol fluorescence assays, additional free retinol inhibits STRA6-mediated retinol release. In contrast, β-ionone enhances STRA6’s vitamin A uptake activity in all assays. β-ionone also relieves free retinol’s inhibition of STRA6-catalyzed retinol release. RDH (with NADP) enhances STRA6-catalyzes retinol release from holo-RBP by converting retinol to retinal. Lower figure: STRA6 catalyzes retinol loading into apo-RBP. However, this activity is inhibited by LRAT, which converts retinol to retinyl esters, by CRBP-I, which binds to retinol with high affinity and β-ionone, which competes with retinol in the loading reaction. (B) Schematic diagram of STRA6’s vitamin A uptake mechanism from holo-RBP.

DISSCUSSION

By combining two newly developed real-time monitoring techniques with radioactive retinoid-based and HPLC-based techniques (Supplemental Table), this study revealed the mechanism of STRA6-mediated substrate uptake and its ability to couple to distinct intracellular proteins. This study also found that no intracellular protein is absolutely required for enhanced STRA6 activity and that it is possible for a small molecule to stimulate STRA6-mediated vitamin A uptake. STRA6-catalyzed retinol release from RBP is largely responsible for the endocytosis-independent uptake of retinol, but STRA6 does not simply function as a “bottle opener”, if RBP is analogous to a “bottle” that holds vitamin A. Instead, STRA6-mediated retinol uptake is coupled to CRBP-I and LRAT (but not to the cell membranes, despite their much larger capacity to store retinol). This coupling mechanism depends on the robust STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading, which inhibits further retinol release. In simpler terms, STRA6-catalyzed retinol release and STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading largely (but not completely) cancel each other’s action. Anything (e.g., LRAT, CRBP-I, or β-ionone) that effectively blocks STRA6-catalyzed retinol loading can enhance STRA6’s vitamin A uptake. However, STRA6-mediated retinol loading shows a distinct biphasic characteristic not observed in STRA6-mediated retinol release, as revealed by real-time analyses. If STRA6 has equal opportunities to release retinol or to load retinol, the loading activity predominates initially. The distinct kinetic features of STRA6’s retinol loading and release activities suggest that RBP’s loss of retinol changes the nature of its interaction with STRA6, analogous to the differential interactions of holo-RBP and apo-RBP with TTR. This coupling mechanism’s existence also depends on a finely balanced RBP/STRA6 interaction. It would not exist if RBP dissociated from STRA6 immediately after losing retinol, in analogy to RBP’s immediate loss of binding to TTR after losing retinol (12). On the other hand, a very stable RBP/STRA6 interaction would prevent further delivery of retinol by the next RBP. This model of coupling uptake to storage is distinct from all previously published possible mechanistic models of the RBP receptor. For example, no previous model can explain the unexpected finding that a vitamin A analog can drastically enhance (not suppress) RBP receptor-mediated vitamin A uptake.

The fact that β-ionone potently stimulates STRA6-mediated vitamin A uptake suggests that CRBP-I and LRAT are not absolutely required for enhanced STRA6 activity and that small molecules can stimulate STRA6’s vitamin A uptake activity. β-ionone’s ability to enhance cellular vitamin A uptake in a STRA6-dependent manner and in a potency similar to that of CRBP-I suggests a strategy to stimulate STRA6’s vitamin A uptake without a need to increase intracellular expression of CRBP-I or LRAT. Given the specific and dose-dependent nature of β-ionone’s effect, β-ionone or related compounds can be potentially employed to treat human diseases caused by insufficient tissue retinoid levels (28–30). This advantage of this strategy is that it specifically stimulates a natural cellular vitamin A uptake mechanism in cells that naturally take up vitamin A.

The mechanism identified here is notably different from known cellular uptake mechanisms including other receptor-mediated and endocytosis-independent mechanisms (31, 32). It enables STRA6 to take up vitamin A bound with high affinity to its extracellular carrier protein without using cellular energy (like a primary or secondary active transporter) or a preexisting electrochemical gradient of the substrate (like a channels or facilitated transporter). Why did evolution come up with such a new mechanism instead of using an existing one, such as ATP-dependent transport (32) to pump vitamin A into cells? This coupling mechanism is analogous to a pressure-dependent water tap that only opens when water is needed and therefore prevents flooding. This mechanism offers exquisite control of vitamin A uptake from the cell surface, preventing vitamin A toxicity due to the potent and broad biological activities of retinoids, especially in regulating gene transcription during development and in adults (33, 34).

METHODS

Methods are described in detail in the Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Ribalet, K. Philipson, E. Wright, D. Bok, G. Fain, W. Hubbell, J. Nathans, R. Kaback, and B. Khakh for helpful discussion and/or suggestions on the paper, J. Parker for building the LED light source, and A. Rattner for providing the plasmid for retinol dehydrogenase. Supported by NIH grant 5R01EY018144 (H.S.). H.S. is an Early Career Scientist of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: This material is available free of charge via the Internet.

References

- 1.Wald G. The molecular basis of visual excitation. Nature. 1968;219:800–807. doi: 10.1038/219800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dowling JE, Wald G. VITAMIN A DEFICIENCY AND NIGHT BLINDNESS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1958;44:648–661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.7.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Travis GH, Golczak M, Moise AR, Palczewski K. Diseases caused by defects in the visual cycle: retinoids as potential therapeutic agents. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:469–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziouzenkova O, Orasanu G, Sharlach M, Akiyama TE, Berger JP, Viereck J, Hamilton JA, Tang G, Dolnikowski GG, Vogel S, Duester G, Plutzky J. Retinaldehyde represses adipogenesis and diet-induced obesity. Nat Med. 2007;13:695–702. doi: 10.1038/nm1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans RM. The molecular basis of signaling by vitamin A and its metabolites. Harvey Lect. 1994;90:105–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mark M, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P. Function of retinoid nuclear receptors: lessons from genetic and pharmacological dissections of the retinoic acid signaling pathway during mouse embryogenesis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:451–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith FR, Goodman DS. Vitamin A transport in human vitamin A toxicity. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:805–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197604082941503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nau H, Chahoud I, Dencker L, Lammer EJ, Scott WJ. Vitamin A in Health and Disease. Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1994. Teratogenicity of Vitamin A and Retinoids; pp. 615–664. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins MD, Mao GE. Teratology of retinoids. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;39:399–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penniston KL, Tanumihardjo SA. The acute and chronic toxic effects of vitamin A. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:191–201. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blomhoff R, Green MH, Berg T, Norum KR. Transport and storage of vitamin A. Science. 1990;250:399–404. doi: 10.1126/science.2218545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanotti G, Berni R. Plasma retinol-binding protein: structure and interactions with retinol, retinoids, and transthyretin. Vitam Horm. 2004;69:271–295. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(04)69010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quadro L, Hamberger L, Gottesman ME, Wang F, Colantuoni V, Blaner WS, Mendelsohn CL. Pathways of vitamin A delivery to the embryo: insights from a new tunable model of embryonic vitamin A deficiency. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4479–4490. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Q, Graham TE, Mody N, Preitner F, Peroni OD, Zabolotny JM, Kotani K, Quadro L, Kahn BB. Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2005;436:356–362. doi: 10.1038/nature03711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouillet P, Sapin V, Chazaud C, Messaddeq N, Decimo D, Dolle P, Chambon P. Developmental expression pattern of Stra6, a retinoic acid-responsive gene encoding a new type of membrane protein. Mech Dev. 1997;63:173–186. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szeto W, Jiang W, Tice DA, Rubinfeld B, Hollingshead PG, Fong SE, Dugger DL, Pham T, Yansura DG, Wong TA, Grimaldi JC, Corpuz RT, Singh JS, Frantz GD, Devaux B, Crowley CW, Schwall RH, Eberhard DA, Rastelli L, Polakis P, Pennica D. Overexpression of the retinoic acid-responsive gene Stra6 in human cancers and its synergistic induction by Wnt-1 and retinoic acid. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4197–4205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawaguchi R, Yu J, Honda J, Hu J, Whitelegge J, Ping P, Wiita P, Bok D, Sun H. A membrane receptor for retinol binding protein mediates cellular uptake of vitamin A. Science. 2007;315:820–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1136244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drager UC. Retinoic acid signaling in the functioning brain. Sci STKE 2006. 2006:pe10. doi: 10.1126/stke.3242006pe10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maden M. Retinoic acid in the development, regeneration and maintenance of the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:755–765. doi: 10.1038/nrn2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasutto F, Sticht H, Hammersen G, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Fitzpatrick DR, Nurnberg G, Brasch F, Schirmer-Zimmermann H, Tolmie JL, Chitayat D, Houge G, Fernandez-Martinez L, Keating S, Mortier G, Hennekam RC, von der Wense A, Slavotinek A, Meinecke P, Bitoun P, Becker C, Nurnberg P, Reis A, Rauch A. Mutations in STRA6 Cause a Broad Spectrum of Malformations Including Anophthalmia, Congenital Heart Defects, Diaphragmatic Hernia, Alveolar Capillary Dysplasia, Lung Hypoplasia, and Mental Retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:550–560. doi: 10.1086/512203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isken A, Golczak M, Oberhauser V, Hunzelmann S, Driever W, Imanishi Y, Palczewski K, von Lintig J. RBP4 Disrupts Vitamin A Uptake Homeostasis in a STRA6-Deficient Animal Model for Matthew-Wood Syndrome. Cell Metab. 2008;7:258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golczak M, Maeda A, Bereta G, Maeda T, Kiser PD, Hunzelmann S, von Lintig J, Blaner WS, Palczewski K. Metabolic basis of visual cycle inhibition by retinoid and nonretinoid compounds in the vertebrate retina. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9543–9554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708982200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ong DE, Chytil F. Specificity of cellular retinol-binding protein for compounds with vitamin A activity. Nature. 1975;255:74–75. doi: 10.1038/255074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Napoli JL. A gene knockout corroborates the integral function of cellular retinol-binding protein in retinoid metabolism. Nutr Rev. 2000;58:230–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2000.tb01870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghyselinck NB, Bavik C, Sapin V, Mark M, Bonnier D, Hindelang C, Dierich A, Nilsson CB, Hakansson H, Sauvant P, Azais-Braesco V, Frasson M, Picaud S, Chambon P. Cellular retinol-binding protein I is essential for vitamin A homeostasis. Embo J. 1999;18:4903–4914. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li E, Norris AW. Structure/function of cytoplasmic vitamin A-binding proteins. Annu Rev Nutr. 1996;16:205–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.001225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawaguchi R, Yu J, Wiita P, Honda J, Sun H. An essential ligand-binding domain in the membrane receptor for retinol-binding protein revealed by large-scale mutagenesis and a human polymorphism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15160–15168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801060200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maden M, Hind M. Retinoic acid in alveolar development, maintenance and regeneration. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:799–808. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vahlquist A. Role of Retinoids in Normal and Diseased Skin. In: Blomhoff R, editor. Vitamin A in Health and Disease. Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1994. pp. 365–424. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu L, Ross AC. Acidic retinoids synergize with vitamin A to enhance retinol uptake and STRA6, LRAT, and CYP26B1 expression in neonatal lung. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:378–387. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M001222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschulz KT, Xu S, Hobbs HH, Krieger M. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science. 1996;271:518–520. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hvorup RN, Goetz BA, Niederer M, Hollenstein K, Perozo E, Locher KP. Asymmetry in the structure of the ABC transporter-binding protein complex BtuCD-BtuF. Science. 2007;317:1387–1390. doi: 10.1126/science.1145950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petkovich M, Brand NJ, Krust A, Chambon P. A human retinoic acid receptor which belongs to the family of nuclear receptors. Nature. 1987;330:444–450. doi: 10.1038/330444a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giguere V, Ong ES, Segui P, Evans RM. Identification of a receptor for the morphogen retinoic acid. Nature. 1987;330:624–629. doi: 10.1038/330624a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.