Abstract

Temperament was examined as a moderator of maternal parenting behaviors, including warmth, negativity, autonomy granting, and guidance. Observations of parenting and questionnaire measures of temperament and adjustment were obtained from a community sample (N=214; ages 8–12). Trajectories of depression and anxiety were assessed across 3 years. The pattern of parenting as a predictor of internalizing symptoms depended on temperament. Maternal negativity predicted increases in depression for children low in fear. Effortful control moderated sensitivity to maternal negativity, autonomy granting, and guidance. Children low in effortful control reported more symptoms in the presence of negative or poor-fitting parenting. The results support differential responding, but also suggest that temperament may render children vulnerable for the development of problems regardless of parenting.

Keywords: Temperament, Parenting, Child depression, Child anxiety

Research indicates that parenting and children’s temperament are risk factors that might influence the development of internalizing symptoms. Although each factor is important in shaping the trajectory of children’s adjustment, models examining each as an individual determinant of development may be simplistic. Rather, children might vary in their sensitivity to parents’ behaviors depending on their emotionality and self-regulation (Wachs 1991). A greater understanding of the emergence of internalizing problems may be gained by examining how specific temperament dimensions moderate the relation of parenting to internalizing symptoms, thereby clarifying models of differential responding. Further, this study examined predictors of commonalities and differences in the trajectories of depression and anxiety during pre-adolescence. The use of latent growth models provides an expanded understanding of parenting-by-temperament interactions in predicting the course of internalizing symptoms.

Risk Factors in the Development of Internalizing Problems

Parenting and children’s temperament characteristics are two important risk factors in the development and maintenance of internalizing problems. Because depression and anxiety are correlated and often co-occur, researchers frequently investigate depression and anxiety as a single domain of problems, internalizing symptoms, implying that these disorders are not differentiated in childhood. However, researchers have been able to distinctly classify children as depressed or anxious suggesting differences in etiology. There are also differences in the core emotional components of each, including low positive affect or sadness for depression and fear for anxiety (e.g., Brandy and Kendall 1992). It may be important to identify processes that distinguish the development of anxiety and depression (Miller et al. 2009).

Parenting

The development of internalizing problems has been linked with specific parenting behaviors including negativity, hostility and over-control (Rapee 1997), each of which may differentially relate to depression and anxiety. Parental rejection may be more strongly related to children’s depression, whereas parental control behaviors may be more specific to anxiety (McLeod et al. 2007; Rapee 1997). Specifically, parenting that is less warm or more rejecting relates to depression (Muris et al. 2001). Parental control is conceptualized along multiple dimensions, including guidance and autonomy granting. Guidance facilitates children’s competent navigation of tasks (Dennis 2006) and may promote emotion regulation and problem solving. Autonomy granting is the degree to which parents allow or restrict children’s independence (Silk et al. 2003). A meta-analysis revealed a large effect size for the relation between low autonomy and anxiety (McLeod, et al. 2007). Further, guidance and autonomy granting may be particularly important during the transition to adolescence, as children increase in their independence (Barber 1996).

Temperament

Temperament is defined as physiologically-based individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation that are genetically based, stable, and yet shaped by experience (Rothbart and Bates 2006). Temperament is an important predictor of psychopathology. Aspects of emotionality are unique risk factors for depression and anxiety. Specifically, the tripartite model (see De Bolle and De Fruyt 2010) suggests that negative emotionality confers risk for internalizing disorders generally, whereas low positive affect is a vulnerability for depression (Albano et al. 2003). Notably, the construct of negative emotionality includes fearfulness and irritability, which originate from distinct motivational systems (see Derryberry and Rothbart 1997). Further, each may operate differently in predicting anxiety and depression, as fearfulness may be a unique risk factor for anxiety (Muris 2006), whereas irritability may confer risk for psychopathology more generally (Rothbart and Bates 2006). As for regulation, effortful control, which includes inhibitory control and attention regulation (Rothbart et al. 2001), has been linked to the emergence of psychopathology, including depression and anxiety (Muris et al. 2008).

Models of Differential Responding

A bioecological model underlies several theories that posit how children’s temperamental characteristics lead to variation in sensitivity to rearing behaviors. One such model is a vulnerability model, which suggests that children with a particular temperament characteristic are more likely to develop adjustment problems despite low contextual risk (Nigg 2006). Alternatively, a diathesis-stress model proposes differential responding to parenting such that temperament exacerbates the effects of other risk factors, increasing the adverse impact of risk (Ingram and Luxton 2005). Goodness-of-fit models suggest that adjustment stems from the match between individuals’ characteristics and environmental demands (Lerner and Lerner 1994). However, other models make more nuanced predictions. In particular, biological sensitivity to context purports that some individuals are highly permeable or susceptible to environmental conditions, positive or negative, while others are largely unaffected by environmental circumstance (Boyce and Ellis 2005). Belsky’s differential susceptibility hypothesis posits that children with temperamental vulnerabilities will be more sensitive to parenting, benefitting more from positive parenting and being more adversely affected by negative parenting (Belsky and Pluess 2009). Thus, children with temperamental vulnerabilities will flounder in the face of negative parenting and flourish in the presence of positive parenting. Notably, consideration of this framework in this study is specific to models of developmental psychopathology, as aspects of positive adjustment were not tested.

Mounting evidence suggests that models of differential responding may be important in explaining parenting and temperament as predictors of children’s internalizing problems. Several studies support the interaction of fear and parenting behaviors in predicting symptoms, with some evidence for both vulnerability and differential responding models. In a study of early childhood, increases in internalizing symptoms were uniquely observed in boys high in fear and negative emotionality. However, these increasing trajectories were attenuated when mothers were high in negative control, suggesting a counterintuitive protective role for negativity (Gilliom and Shaw 2004). In cross-sectional studies with older children, support has also been demonstrated for differential responding based on fearfulness. Parental over-involvement and harsh discipline were positively related to depression for fearful, school-age boys (Colder et al. 1997). In preadolescent youth, perceptions of maternal rejection related to higher depressive symptoms for fearful girls. However, parental warmth and overprotection did not interact with fear, which instead presented a vulnerability for depressive symptoms (Oldehinkel et al. 2006). In these studies of internalizing problems, fearless children were not differentially sensitive to parenting.

There has been mixed support or children’s differential responding across levels of temperamental irritability. Irritable distress did not interact with parental negativity in a sample of school-age children (Morris et al. 2002). Conversely, in preadolescents irritability was related to higher depressive symptoms when parents were perceived as low in warmth (Oldehinkel et al. 2006). This pattern was unique to children high in irritability. More support has been demonstrated for variations in sensitivity to maternal control. In a small sample of school children, psychological control was related to higher internalizing symptoms only for children high in irritability (Morris et al. 2002). Similarly, in preadolescents, high irritability combined with high maternal overprotection was related to more depressive symptoms. Further, the pattern of results was largely consistent with Belsky’s differential susceptibly hypothesis, suggesting that easily frustrated children may be more sensitive to negative parenting. Notably, gender did not moderate these interactions (Oldehinkel et al. 2006).

Few studies have examined the moderating effects of positive affect and effortful control. Positive affect conditioned children’s sensitivity to parenting, as rejection was cross-sectionally related to depressive symptoms for children low in positive affect (Lengua et al. 2000). Only one study has examined parenting interacting with effortful control to predict internalizing problems, and the interaction was not significant (Morris et al. 2002). However, this study used a small sample and cross-sectional design. Overall, fear, irritability and positive affect appear to render some children sensitive to parenting. However, relatively few studies have examined differential responding in predicting internalizing problems.

This Study

Emerging research suggests that the relation of parenting to children’s internalizing problems is likely to be moderated by children’s temperament. Yet most studies have used cross-sectional designs, few have considered internalizing problems, and none has examined trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms. The present study used latent growth models to test the direct and moderated relation of parenting and temperament on the development and course of internalizing symptoms. Further, anxiety and depression were examined separately to identify differences in relations with parenting and temperament, potentially highlighting distinct pathways and enhance models of developmental psychopathology.

Specifically, we tested whether the relations of parenting to changes in depression and anxiety symptoms were moderated by children’s fear, irritability, positive affect, and effortful control. We hypothesized that maternal parenting would predict children’s depression and anxiety symptoms. Guided by theory and research (Rapee 1997), low maternal warmth was expected to more strongly predict depression while high maternal control was expected to more strongly predict anxiety. In addition, we hypothesized that child temperament would moderate associations of parenting with symptoms, demonstrating support for differential responding to parenting. We expected that children with high fear or irritability, or low positive affect or effortful control would be more susceptible to negative parenting (e.g., low warmth, autonomy granting, and guidance or high negativity) showing increases in or the maintenance of symptoms.

Method

Participants

Participants were a community-based sample of 214 children and their mothers who were assessed during in-home interviews at three time points, each separated by 1 year. Time 1 interviews began when children were in the 3rd through 5th grades (M=9.48 years, SD=1.01, range = 8–12). The sample included 56% female children (n=121). Participants were recruited through children’s public school classrooms. Selected schools represented a variety of sociodemographic characteristics of the Pacific Northwest urban area surrounding the university. Approximately 1,280 information forms were distributed to 59 classrooms in 13 schools; 697 families returned the form with 313 indicating interest. The target sample size for this study was about 200 families. If there was more than one child per family in the target grades, one child was randomly selected to participate. Children with developmental disabilities (except learning disabilities) and families not fluent in English were excluded from the study to ensure adequate comprehension of the questionnaire measures. A female primary caregiver was required to participate, whereas a male caregiver’s participation was optional. Only data from the interviews of the female caregivers and children were used in the current study.

Annual family income was evenly distributed with approximately 11% of families earning less than 20,000 per year, 20% between 21,000 and 40,000, 17% between 41,000 and 60,000, 17% between 61,000 and 80,000, 19% between 81,000 and 100,000, and 16% above 100,000. The sample included 16% African American, 3% Asian American, 70% European American, 4% Latino or Hispanic, 2% Native American, and 5% children with multiple ethnic or racial backgrounds. Mothers were generally well educated with a modal level of educational attainment at a college or university graduate. Seventy percent of families consisted of two-parent households.

Attrition was low with 91.6% of participants remaining at Time 3. Missing data (n=4) at time 1 was due to technical problems and is therefore missing at random. Participants with missing data on any variable at times 2 or 3 were compared to those with complete data on all variables: demographics (child sex and age, family income, maternal depression), parenting (warmth, negativity, autonomy granting, guidance and structure), temperament (fear, irritability, positive affect, effortful control), and outcomes (depression and anxiety). The t tests indicated that participants with any missing data (n=25) differed from those with no missing data (n=189) only on income (missing, M=4.92, SD=3.03; no missing, M=6.87, SD=3.15, t (208) = 2.86, p<0.01). However, the relation of income to missingness was a small effect (r=−0.195, p<0.01) and did not reach previously cited thresholds for introducing substantial bias (e.g., r>0.40; see Collins et al. 2001) suggesting little bias was introduced due to missing data.

Procedure

Structured 2.5-hour interviews were conducted in families’ homes during which the parent–child interaction tasks were recorded and questionnaire measures were administered. After confidentiality was explained, mothers signed informed consent forms and children signed assent forms indicating that children’s responses would not be shared with their mothers unless there was concern about child safety (i.e., high level of depression, suicidal ideation, or child abuse). Dyads participated in a series of parent–child interaction tasks administered by trained interviewers and video-recorded for later observational coding. Following the interaction tasks, mother and child participants were interviewed individually (in separate rooms when possible) by trained interviewers. Questionnaire measures were administered orally, with the interviewers reading instructions and all items to participants in order to minimize errors in interpretation and address potential problems with literacy in parents and children. Dyads were scheduled for subsequent assessments approximately 1 (M=1.04, SD=0.11) and 2 (M=2.00, SD=0.15) years after their initial assessment. Families received $40 compensation for participating at Time 1, with the compensation increasing by $10 each additional year the families participated.

Measures

Covariates

Previous research has linked family income and maternal depression with parenting and children’s adjustment. Therefore, these variables were examined as potential covariates. Income was reported by mothers as the family’s average annual income from all sources at Time 1. Maternal self-report of depressive symptoms was gathered on the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977; α for the current sample = 0.91). Responses were provided on a 4-point scale (0 = never to 3 = often).

Gender differences in mean levels of temperament (girls higher in fear and EC, boys more irritable; Else-Quest et al. 2006) and internalizing disorders have been reported. However, consistent gender-moderated relations with adjustment have not emerged (Rothbart and Bates 2006). The onset of gender differences in internalizing disorders is unclear, with some estimates in early adolescence (Gullone et al. 2001) and others in mid-adolescence (Hankin et al. 1998). Therefore, gender was covaried in all models.

Parenting Behaviors

Maternal parenting behaviors were measured at Time 1 during two 5-minute parent–child interaction tasks (Lindahl and Malik 2000). The first task aimed to sample behavior during a neutral interaction. Dyads were asked to discuss the child’s day at and after school. In the second task, the dyad was asked to discuss and attempt to resolve a recent conflict. Each participant was given a list of six common parent–child conflict domains (e.g., chores, homework, etc.) and asked to circle all areas that had been the subject of recent disagreement. The interviewer then selected a domain endorsed by both the parent and child.

Subsequently, the parent–child interaction tasks were coded for mothers’ warmth, negativity, guidance and structuring, and autonomy granting (Cowan and Cowan 1992; Lindahl and Malik 2000). Global codes were assigned from a 5-point Likert scale (1 = little or no behavior to 5 = highest level of maternal behavior). The coding manual is available upon request from the second author. Reliability was assessed by double coding 20% of videotapes. Intra-class correlations (ICC) for each parenting behavior are reported below. Global codes for maternal warmth (ICC = 0.94) indicated the degree of positivity expressed by the mother including her degree of affection, smiling, and laughter. Maternal negativity (ICC = 0.93) measured the overall negative tone or level of tension expressed by the mother including clear expression of frustration, anger, irritation, and hostility. Guidance and structure (ICC = 0.89) assessed the overall level of guidance, outlining, and expectation explanation about the task provided by the mother. Low scores indicated a lack of planning and expectation, whereas, high scores reflected mothers clearly outlining and providing suggestions for navigating the conversations. Mothers who over-structured the task received a low score on the next dimension, autonomy granting. Maternal autonomy granting (ICC = 0.94) captured parental behaviors that facilitate a range of the child’s autonomous expression. Low scores reflected maternal behavior that served to control and monopolize the conversation. High scores reflected the encouragement of autonomous participation while still maintaining a parental role. In an effort to increase the amount of maternal behavior sampled and capture behaviors across different emotional contexts, codes were aggregated across the discussion of the day and conflict resolution tasks, using a mean weighted sum to compute a single indicator for each parenting behavior. Maternal behaviors across tasks were significantly and moderately correlated in the expected directions (rs ranged from 0.38 to 0.65).

Child Temperament

Fear, irritability, positive affect, and effortful control were assessed using combined parent and child report questionnaire measures at Time 1. Questionnaire measures of temperament capture perspectives across contexts, allowing reporters to consider multiple experiences and conditions (see Rothbart and Bates 2006). Child and mother-reports on the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire (EATQ; Capaldi and Rothbart 1992) were used to measure children’s Fear (6 items), Irritability (8 items), and Attention Regulation (8 items). Notably, the internal consistency for mother-reported fear on the EATQ was unacceptably low (α = 0.40), and was therefore augmented with two items from the Emotionality, Activity, and Sociability Scale (EAS; Buss and Plomin 1984) negative emotionality subscale. The additional items were “Your child is easily frightened” and “Your child has fewer fears than other children his/her age (R)”. The alpha for the augmented mother-report scale was 0.53. Reports on the Child Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Goldsmith and Rothbart 1991) assessed Inhibitory Control (12 items) and Smiling and Laughter (11 items). Although this scale was developed to assess temperament in children ages 3 to 7, previous research has reliably used the measure with children ages 8 to 12 (Lengua and Long 2002; Morris et al. 2002). The attention regulation (EATQ) and inhibitory control (CBQ) subscales were combined to assess effortful control. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very false to 5 = very true).

Multi-reporter measures of temperament were sought to reduce the effects of shared method variance and potential reporter bias (Wachs 1991). Aggregate measures increase reliability by including varying perspectives and reducing error (Noordhof et al. 2008). A prior confirmatory factor analysis supported the feasibility of combining reporters (average factor loading was 0.46; see Lengua 2006). Thus, composite measures were created by averaging the scaled scores for fear, irritability, positive affect, and effortful control across mother and child reports. For fear the composite alpha (calculated by taking into account the alpha and variance for each reporter and the covariance between scales) was 0.64 (mother report α = 0.53; child report α = 0.61). The composite alpha for irritability was 0.74 (mother report α = 0.75; child report α = 0.71), for positive affect was 0.82 (mother report α = 0.81; child report α = 0.80), and for effortful control was 0.85 (mother report α = 0.86; child report α = 0.75).

Child Depression and Anxiety

Children’s self-report of internalizing symptoms were used given that anxiety and depression are characterized by disruptions in internal experiences. Therefore, reports that capture children’s perceptions of their affective and emotional states (rather than observations of behaviors) are thought to be more accurate. Further, children are reliable and accurate reporters of their mood (Ialongo et al. 2001). The 27-item Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs 1981) measured children’s depressive symptoms. Children rated their depression symptoms by selecting one of three statements of increasing severity. Reliability estimates have consistently been greater than 0.71 (Kovacs 1981). The alpha for the current sample was 0.82 at time 1. The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS, Reynolds and Richmond 1978) assessed the degree and quality of anxious symptoms. In this study, 19 items from the Physiological Anxiety and Worry subscales were included to minimize overlap with the measure of depression (sample excluded items: I felt tired a lot; Other kids were happier than I was; I got mad easily). Children indicated the presence or absence of each item (1 = no, 2 = yes) and the alpha was 0.85 at time 1.

Analytic Plan

Families were included if they had available data from at least one time point. Data analyses were conducted using Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation (FIMLE). FIMLE requires estimation of means and intercepts, as well as covariances and path coefficients, and uses all the data available simultaneously to calculate parameter estimates. FIMLE has been found to be less biased and more efficient than other techniques for missing data (see Arbuckle 1996). Our examination of bias in missing data (see above) suggested that the pattern of missing data introduced minimal bias and aligned with the assumptions of FIMLE.

Data were analyzed using Latent Growth Curve Analysis (LGC) to evaluate how parenting at the first time point predicted initial levels and trajectories of depressive and anxiety symptoms across 3 years. Based on the Muthén and Curran (1997) method for power calculations, the current sample size of 214 provided adequate power to test the proposed models. Maternal warmth, negativity, guidance and structure, and autonomy granting were tested as simultaneous predictors of changes in depression and anxiety to examine their unique contributions to children’s symptoms. Temperament variables were entered to test whether child characteristics served as direct predictors of levels and trajectories of symptoms and moderators of parenting, allowing examination of different associations between parenting and child symptoms across levels of temperament. Additionally, because LGC considers change over time, three-way interactions (parenting by temperament by time) were examined with symptom changes (Time) as the focal predictor1 (Preacher et al. 2006).

Before testing the study hypotheses, covariate models were specified in which trajectories of symptoms were conditioned on four covariates. The covariate models included variables related to child symptoms (i.e., gender with female = 1, male = 2 and age at time 1) and family risk factors (i.e., income and maternal depression). To preserve power for testing interactions, non-significant covariates were dropped from subsequent models. Given the moderate to high co-occurrence of anxiety and depression, non-corresponding symptoms were included as time-varying covariates. The trajectory of anxiety was modeled after accounting for time-specific relations with depression, allowing unique prediction of anxiety, and vice versa for depression.

Results

Correlations among Study Variables

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for all variables. Correlations among the covariates, parenting, temperament, and child symptoms are reported in Table 2. Correlations of child gender, age, income and maternal depression supported consideration as covariates.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for predictor and outcome variables

| Variable | M | SD | Range | Skew |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | ||||

| Maternal depression | 17.38 | 9.86 | 1.00–53.00 | 0.81 |

| Warmth | 7.00 | 1.74 | 2.00–10.00 | −0.39 |

| Negativity | 2.41 | 0.87 | 2.00–7.00 | 2.61 |

| Autonomy granting | 8.14 | 1.79 | 3.00–10.00 | −0.65 |

| Guidance and structure | 7.81 | 1.66 | 2.00–10.00 | −0.73 |

| Fear | 21.37 | 3.59 | 9.00–31.5 | 0.01 |

| Irritability | 26.15 | 3.87 | 17.50–37.00 | 0.10 |

| Positive affect | 43.69 | 4.07 | 33.00–52.50 | −0.14 |

| Effortful control | 35.40 | 3.90 | 22.75–44.00 | −0.28 |

| Depression | 5.63 | 5.03 | 0.00–27.00 | 1.53 |

| Anxiety | 24.39 | 4.35 | 19.00–37.00 | 0.89 |

| Time 2 | ||||

| Depression | 4.78 | 5.07 | 0.00–31.00 | 1.90 |

| Anxiety | 22.87 | 4.08 | 19.00–37.00 | 1.46 |

| Time 3 | ||||

| Depression | 4.28 | 5.08 | 0.00–34.00 | 2.35 |

| Anxiety | 21.96 | 3.35 | 19.00–37.00 | 1.57 |

Table 2.

Correlations among covariates, parenting, temperament, and internalizing symptoms

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

| 1. Child gender | 0.08 | −0.08 | 0.14* | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.22** | −0.15* | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.13† | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.11† |

| 2. Child age TI | – | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.13† | −0.14* | −0.10 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.03 | −0.10 | −0.19** | −0.14* |

| 3. Family income T1 | – | −0.32** | 0.01 | −0.17* | 0.21** | 0.25** | −0.15* | −0.20** | 0.12 | 0.16* | −0.15* | −0.26*** | −0.18** | −0.26*** | −0.23** | −0.17* | |

| 4. Maternal depression T1 | – | −0.09 | 0.11† | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.11† | 0.13† | −0.15* | −0.20** | 0.17* | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.15* | 0.11 | 0.10 | ||

| 5. Warmth | – | −0.44*** | 0.58*** | 0.44*** | −0.08 | −0.14* | 0.16* | 0.17** | −0.18** | −0.16* | −0.22*** | −0.19** | −0.11 | −0.13† | |||

| 6. Negativity | – | −0.62*** | −0.33*** | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.10 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.24*** | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.09 | ||||

| 7. Autonomy granting | – | 0.54*** | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.10 | −0.12† | −0.21*** | −0.11 | −0.05 | −0.04 | |||||

| 8. Guidance and structure | – | 0.03 | −0.13† | 0.09 | 0.11 | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.17* | −0.14* | −0.09 | 0.01 | ||||||

| 9. Fear | – | 0.44*** | 0.09 | −0.21*** | 0.24*** | 0.13† | 0.02 | 0.44*** | 0.22*** | 0.21*** | |||||||

| 10. Irritability | – | −0.04 | −0.37*** | 0.34*** | 0.24*** | 0.08 | 0.37*** | 0.26*** | 0.18** | ||||||||

| 11. Positive affect | – | 0.22** | −0.20** | −0.21** | −0.21** | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.02 | |||||||||

| 12. Effortful control | – | −0.46*** | −0.36*** | −0.32*** | −0.39*** | −0.34*** | −0.29*** | ||||||||||

| 13. Depression T1 | – | 0.56*** | 0.50*** | 0.64*** | 0.52*** | 0.46*** | |||||||||||

| 14. Depression T2 | – | 0.69*** | 0.41*** | 0.69*** | 0.60*** | ||||||||||||

| 15. Depression T3 | – | 0.43*** | 0.49*** | 0.54*** | |||||||||||||

| 16. Anxiety T1 | – | 0.59*** | 0.43*** | ||||||||||||||

| 17. Anxiety T2 | – | 0.59*** |

Column 18 refers to associations with Anxiety at T3

p<0.12,

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Several parenting behaviors were related to children’s depression and anxiety, making them plausible predictors of trajectories; however, there were a greater number of significant associations of parenting with depression than anxiety. Temperament was related to symptoms in the expected manner, with fear more consistently and strongly related to anxiety while positive affect was related to depression. Irritability and effortful control correlated with symptoms. As expected moderate associations between symptoms were observed.

Tests of Changes in Symptoms

Latent growth curve models were used to examine the trajectories of depression and anxiety over time. Using FIMLE in Mplus Version 4.2 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2006), models were specified in which factor loadings were set to define the intercept as levels of symptoms at time 1 and the slope as linear change across 3 years. Consistent with the assumptions of LGC, growth factors were first examined without predictors to examine variability in levels and changes of children’s depression and anxiety symptoms. These models demonstrated adequate fit to the data (depression: χ2 (1) = 0.29, p=0.59, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA <0.001; anxiety χ2 (1) = 1.98, p=0.16, CFI = 99, RMSEA = 0.07) and indicated that symptoms decreased, on average, across the study, but that there was significant variability in the slopes of depression and anxiety. Additionally, although the average trajectory in the sample was decreasing, approximately 33% and 25% of the sample reported increases in depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively. The significant variability for the intercept and slope suggested that exogenous predictors might be useful for explaining variability in initial levels and changes.

Covariates as Predictors of Trajectories

Next, a covariate model was tested to determine whether child gender, age at time 1, family income, and maternal depression predicted initial levels and changes in depression or anxiety. A model was specified in which symptoms (i.e. anxiety symptoms in predicting depression and vice versa), gender, age, income, and maternal depression were simultaneous predictors of initial levels and linear change in depression or anxiety. The conditioned depression model fit the data well, χ2 (5) = 7.51, p=0.19, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA= 0.05, p=0.44. Two significant covariates emerged, including gender (b=0.96, p=0.06, β=0.18) predicting the intercept and income predicting the slope (b=−0.20, p<0.001, β=−0.30). Anxiety was related to depression at Time 1 and 2, but not Time 3 (Time 1: b=0.83, p<0.001, β=0.73; Time 2: b=0.48, p<0.001, β=0.38; Time 3: b=−0.08, p=0.65, β=−0.05). A parallel model was tested for anxiety. The covariate model fit the data well, χ2 (5) = 6.98, p=0.22, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.04, p=0.49. Only income emerged as a significant predictor of the intercept (b=−0.29, p<0.001, β=−0.30) and slope (b=0.11, p<0.05, β=0.24). Depression at all time points was related to anxiety across time (Time 1: b=0.28, p<0.01, β=0.32; Time 2: b=0.35, p<0.001, β=0.44; Time 3: b=0.29, p<0.01, β=0.44). Based on these analyses, gender and income were retained as covariates.

The Interaction of Parenting and Child Temperament

To test the proposed hypothesis, that the effect of parenting would be moderated by children’s temperament, latent growth curve models were specified in which all four maternal parenting behaviors (i.e. maternal warmth, negativity, guidance and structure, and autonomy granting), a child temperament characteristic (i.e., fear, irritability, positive affect, or effortful control), and the multiplicative of these variables (i.e. parenting × temperament) were entered as predictors. As recommended by Curran et al. (2004), parenting behaviors and child temperament characteristics were mean centered. The centered values were then used to create the multiplicative terms and were entered as covariates in the specified models. Model fit information for the moderated growth models is presented in Table 3. Each model included the non-corresponding child-reported symptoms as a time-varying covariate to control for the correlation between symptoms. Child gender and family income were also included as covariates.2 The results are summarized in Table 4. Several significant interactions emerged and the results were probed using established methods (Curran et al. 2004; Preacher et al. 2006), examining the simple slope at values ±1 SD of the mean for parenting and temperament.

Table 3.

Model fit indicators for moderated growth models of depression and anxiety symptoms

| Overall fit | Parenting × fear | Parenting × irritability | Parenting × positive affect | Parenting × effortful control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: Child Depression Symptoms | ||||

| χ2 (N=214) | 15.23 | 12.29 | 15.70 | 16.52 |

| df | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| RMSEA | 0.035 | 0.011 | 0.038 | 0.042 |

| RMSEA p-value | 0.64 | 0.80 | 0.61 | 0.56 |

| CFI | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Outcome: Child Anxiety Symptoms | ||||

| χ2 (N=214) | 24.74* | 14.91 | 22.24* | 26.47** |

| df | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| RMSEA | 0.070 | 0.034 | 0.063 | 0.075 |

| RMSEA p-value | 0.18 | 0.66 | 0.27 | 0.13 |

| CFI | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01

Table 4.

Parameters from conditioned growth models testing linear trajectories of depression and anxiety symptoms

| Depression growth parameters | Anxiety growth parameters | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept factor | Slope factor | Intercept factor | Slope factor | |||||||||

| b | SE | β | b | SE | β | b | SE | β | b | SE | β | |

| Direct effects | ||||||||||||

| Child gender | 1.02*a | 0.51 | 0.19 | −0.05 | 0.39 | −0.01 | −0.42 | 0.48 | −0.07 | −0.30 | 0.29 | −0.11 |

| T1 family income | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | −0.14* | 0.07 | −0.21 | −0.28*** | 0.08 | −0.30 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.17 |

| Parenting | ||||||||||||

| Warmth | −0.12 | 0.19 | −0.08 | −0.11 | 0.15 | −0.09 | −0.35* | 0.18 | −0.20 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Negativity | −0.09 | 0.39 | −0.03 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.16 | −0.45 | 0.36 | −0.13 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| Autonomy granting | −0.05 | 0.21 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| Guidance and structure | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.09 | −0.15 | 0.14 | −0.12 | −0.12 | 0.17 | −0.07 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.18 |

| Temperamentb | ||||||||||||

| Fear | −0.05 | 0.09 | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.35*** | 0.07 | 0.39 | −0.11** | 0.04 | −0.25 |

| Irritability | 0.16* | 0.08 | 0.24 | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.20** | 0.07 | 0.26 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.14 |

| Positive affect | −0.18** | 0.06 | −0.29 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Effortful control | −0.21*** | 0.08 | −0.31 | −0.09 | 0.06 | −0.17 | −0.24*** | 0.08 | −0.31 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Interactions | ||||||||||||

| Warmth | ||||||||||||

| × Fear | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.10 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| × Irritability | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.12 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.13 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.14 |

| × Positive affect | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.08 |

| × Effortful control | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.12 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.19 |

| Negativity | ||||||||||||

| × Fear | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.14 | −0.44*** | 0.10 | −0.54 | −0.32** | 0.12 | −0.28 | 0.16† | 0.09 | 0.28 |

| × Irritability | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.13† | 0.07 | −0.22 | −0.11 | 0.08 | −0.13 | 0.11* | 0.05 | 0.28 |

| × Positive affect | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.07 | −0.17 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| × Effortful control | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.15 | −0.16*** | 0.06 | −0.40 |

| Autonomy granting | ||||||||||||

| × Fear | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.11 | −0.08† | 0.05 | −0.22 | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| × Irritability | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 |

| × Positive affect | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.14 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.09 |

| × Effortful control | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.07* | 0.03 | −0.33 |

| Guidance and structure | ||||||||||||

| × Fear | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.02 |

| × Irritability | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04 |

| × Positive affect | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| × Effortful control | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.17 | 0.07* | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 |

The magnitude and significance of the association between gender and initial levels of depression symptoms depends on the other variables in the model. When fear, positive affect, or effortful control was entered, gender did not predict the intercept of depression

We considered that the findings could differ across reporters of temperament given modest to moderate correlations across reporter (rs ranged from 0.05 to 0.21). Therefore, we conducted the analyses separately for each reporter. Some differences in the associations that achieved significance emerged, but the overall pattern of magnitude and significance was largely similar to the analyses with combined reports. The pattern of findings suggests no information was lost by aggregating reporters. Aggregated reports of temperament were retained to present a parsimonious summary of the current findings with minimal error in prediction

The results summarized in this table were derived from the results of eight models. One model was specified for each temperament characteristic.

p≤0.10,

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

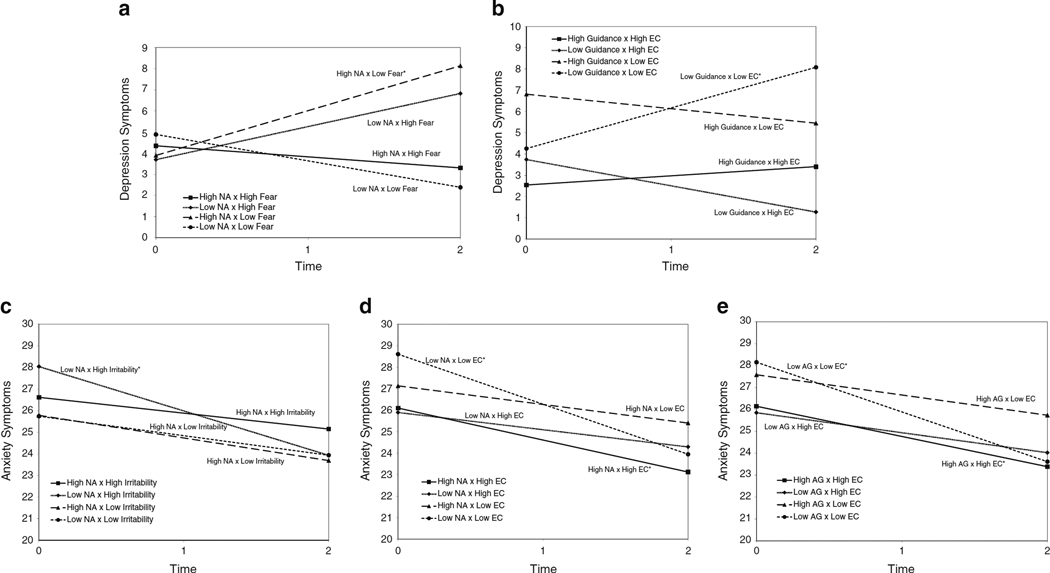

When fear was examined as the moderator, there was a significant interaction effect with maternal negativity in predicting changes in children’s depression. As depicted in Fig. 1a, for children low in fear, high maternal negativity predicted an increase in depression across time (b=2.12 p=0.02). At the end of the study, these children reported the highest levels of depression, after accounting for anxiety symptoms. Children high in fear whose mothers who were low in negativity, reported modest increases in symptoms across the study (b=1.56, p=0.09). Conversely, children low in fear whose mothers’ exhibited low negativity (b=−1.25 p= 0.13) and children high in fear whose mothers’ exhibited high negativity (b=−0.52, p=0.54) reported low, stable levels of depression. None of the other parenting variables interacted with fear to predict levels or trajectories of depression. Children’s irritability and positive affect did not interact with parenting to predict initial levels or changes in depressive symptoms. However, each was directly related with initial levels of depression (see Table 4).

Fig. 1.

(a–e) A plot of the simple slopes of the relation of parenting and temperament on symptoms. Simple slopes are plotted at 1 SD above and below the mean of parenting and temperament (1.5 SD for guidance × effortful control). The X-axis denotes the time in study, across 3 years. NA maternal negativity; AG autonomy granting; EC effortful control. *p < .05

Maternal guidance interacted with effortful control to predict initial levels and changes in depression (Fig. 1b). The simple slopes for this interaction were not significant at conditional values of ±1 SD. Therefore, more extreme conditional values (i.e., ±1.5 SD) were used to facilitate a better understanding of the findings. Children high in effortful control reported fewer symptoms at time 1. Maternal guidance did not predict changes in depression across the study (high guidance: b=0.43, p=0.66; low guidance: b=−1.24, p=0.23), although children high in effortful control whose mothers exhibited low guidance reported the lowest levels of depression at time 3. Conversely for children low in effortful control, higher symptoms were reported across all time points. Further, increases in depression were reported when mothers were observed as low in guidance (high: b=−0.68, p=0.55; low: b=1.91, p=0.048). These results indicate that for children low in effortful control, greater guidance by mothers predicted better adjustment.

For anxiety symptoms, fear interacted with maternal negativity to predict the intercept or initial levels of anxiety. For children high in fear, low maternal negativity was associated with more anxiety symptoms (b=−1.50, p<0.001). However, for children at or below the mean of fear, maternal negativity was not related to initial levels of anxiety (mean: b=−0.33, p=0.32; low: b=0.83, p=0.15). Fear did not interact with any parenting variables to predict changes in anxiety. Instead, fear was negatively related to changes in anxiety across the study, suggesting that higher fear predicted slower declines or the maintenance of anxiety symptoms. Similar to the findings with child depression symptoms, irritability was also positively related to anxiety symptoms at time 1. However in predicting changes in anxiety, maternal negativity interacted with irritability to predicting changes in symptoms across time (see Fig. 1c). The pattern was such that for children high in irritability, low maternal negativity predicted declines in anxiety (b=−2.05, p<0.001), while low negativity predicted the stability of symptoms (b=−0.73, p=0.22). For children low in irritability, fewer anxiety symptoms were reported across the study regardless of maternal negativity (high: b=−1.05, p=0.09; low: b=−0.90, p=0.16). Positive affect did not predict or condition trajectories of anxiety.

There were two significant interactions of effortful control with parenting to predict changes in anxiety (see Fig. 1d and e). Again, children high in effortful control reported lower, stable levels of anxiety, except when mothers exhibited high negativity, which predicted declines in symptoms (b=−1.49, p=0.02). Children low in effortful control entered the study with higher anxiety. However, symptom levels were only maintained in the presence of high negativity (b=−0.87, p=0.16), while low negativity predicted a steep decline in anxiety (b=−2.33, p<0.001).

Children’s effortful control also interacted with maternal autonomy granting to predict changes in anxiety. For children high in effortful control, anxiety symptoms were lower at the start of the study. However, declining trajectories were observed only when coupled with high autonomy granting (b=−1.38, p=0.03). When mothers were low in autonomy granting, children high in effortful control did not report changes in anxiety (b=−0.91, p=0.13). Conversely, low autonomy granting was related to declines in anxiety for children low in effortful control (b=−2.27, p<0.001), while high maternal autonomy granting was not related to changes in symptoms (b=−0.92, p=0.13). These children retained higher levels of anxiety across the study.

Discussion

We examined the interaction of maternal parenting and child temperament in predicting initial levels and changes in children’s depression and anxiety symptoms to evaluate whether children differentially respond to parenting behaviors in the development of internalizing problems. Previous research has demonstrated that child characteristics interact with parenting in predicting internalizing symptoms (e.g., Colder et al. 1997; Morris et al. 2002), but few studies have examined anxiety and depression separately (Oldehinkel et al. 2006). In addition, existing research has largely utilized cross-sectional designs, limiting our understanding of interactive effects on developmental changes in symptoms. This study extended previous research by examining the effects of parenting and temperament on changes in anxiety and depression separately. The results suggest that the association between parenting and adjustment is complex and conditioned. The findings support children’s differential responding to parenting, suggesting that temperament plays a role in determining the degree to which parental behaviors predicted internalizing problems. Generally, the interactions supported general models of differential responding, including diathesis-stress and goodness-of-fit, and in other cases, temperament served as an independent risk factor. Overall, potential pathways for the development of depression and anxiety were identified.

It is important to note that children’s symptom levels were generally decreasing, which is consistent with known trajectories of depression and anxiety during preadolescence (Gullone et al. 2001). However, there was significant variability in individual trajectories with a substantial number of children reporting increases in symptoms. A closer look at this variability showed that children with higher depression and anxiety at the beginning of the study also ended the study with higher symptom levels and reported slower declines over time.

Multiplicative Model of Parenting and Temperament

Although previous research has identified parenting as a risk factor for internalizing problems (Rapee 1997), the findings from this study suggest that the combined effects of parenting and temperament should be considered to more fully understand processes related to changes in depression and anxiety. Specifically, children’s fear, irritability, and effortful control interacted with parenting to predict changes in depression and anxiety. Moreover, the specific parenting-by-temperament interactions differed across internalizing problems, potentially elucidating processes associated with changes in depression and anxiety.

The pattern of findings is complex, however, some general conclusions can be drawn. First, children with temperamental vulnerabilities (i.e., high fear, high irritability, low positive affect, and low effortful control) reported higher symptoms at the start of the study. However, the trajectory of depression and anxiety was predicted by the interaction between parenting and temperament in several cases. Second, of the significant interactions, most were consistent with general models of differential responding to parenting rather than specific models of differential susceptibility. The findings across interactions generally adhered to a diathesis-stress model, in which negative or poor fitting parenting more adversely impacted children with temperamental vulnerabilities. For example, children lower in effortful control reported higher levels of depression at time 1 (Muris et al. 2008). However, when coupled with low maternal guidance, significant increases in depression symptoms were observed, suggesting that these children were more adversely affected by low guidance. This may stem from the child’s reduced ability to divert attention from negative cues, which is exacerbated in the absence of maternal guidance and support in these emotion regulation strategies. The findings across the remaining interactions also generally adhered to a diathesis-stress model, in which negative or poor fitting parenting more adversely impacted children low in effortful control or high in irritability in predicting trajectories of anxiety symptoms.

Additionally, for some interactions, the correspondence or match between parenting and temperament appeared to be important in predicting adjustment. This is consistent with a goodness-of-fit model (Lerner and Lerner 1994) and describes findings that were not in the expected direction, including the interactions of maternal negativity and autonomy granting with fear and effortful control. For example, although the interaction of maternal negativity with fear was consistent with findings from a previous study examining maternal rejection (Oldehinkel et al. 2006), the observed association was not as predicted. For children low in fear, maternal negativity predicted increases in depressive symptoms. Conversely for fearful children, low maternal negativity predicted a modest increase in depression symptoms. These findings suggest the importance of a match between the level of emotional expression by mothers and children’s emotional arousal. Notably, maternal negativity was coded as expressions of rejection and invalidation, has been regarded as harmful for child adjustment, and particularly related to depression (Muris et al. 2001). However, observations of these behaviors might have reflected mothers’ efforts to contain the negative affect of a child who tends to be reactive. Moreover, this seemingly counterintuitive association has been found in other samples examining trajectories of internalizing problems (Gilliom and Shaw 2004), suggesting that what may appear to be invalidation of emotionality might have been efforts to contain children’s fearfulness. Still, the pattern of findings should be considered tentative and require replication.

With regard to anxiety symptoms, maternal negativity and autonomy granting demonstrated similar patterns. In general, children high in effortful control reported lower anxiety across the study. However counter to our expectations, children high in effortful control were also affected by parenting. Notably, correspondence of the level (high versus low) between children’s temperament and mothers’ negativity (e.g., high effortful control/high negativity) predicted decreases in anxiety across the study, while a lack of fit (e.g., high effortful control/low negativity) predicted the stability of symptoms. Thus, these results mirror the relations observed for the negativity-by-fear interactions, in that high maternal negativity is counter intuitively associated with better adjustment outcomes for some children. In addition, for children low in effortful control, low autonomy granting was associated with marked decreases in anxiety symptoms, resembling levels reported by children high in effortful control at the end of the study. This implies that the correspondence between parenting and temperament predicts decreases in anxiety, whereas a lack of fit was related to stable symptom levels. Importantly, autonomy granting has largely been valued as a positive parenting behavior (Silk et al. 2003) and the differential susceptibility model suggests that children low in effortful control would benefit from higher levels of autonomy granting. However, this finding coupled with the beneficial role of higher guidance suggests that children low in effortful control may benefit from more maternal control aimed at facilitating the regulation of emotions and behavior.

Temperament as a Risk Factor

Although this study lends partial support to differential sensitivity to parenting, there were also significant direct effects of temperament, consistent with a vulnerability model (Nigg 2006). Although fearfulness interacted with maternal negativity, the interactive effects failed to fully account for a direct association between fear and changes in anxiety. Thus, fear predicted the maintenance of higher levels of anxiety. Conversely, low positive affect predicted higher depressive symptoms at the start of the study. These differential relations align with a tripartite framework of internalizing disorders (De Bolle and De Fruyt 2010). Additionally, the differential prediction of depression and anxiety supports previous suggestions that fear presents a vulnerability for anxiety but not depression (Nigg 2006), suggesting that prior evidence of fear predicting depression might be accounted for by the co-occurrence of symptoms.

Irritability emerged as a risk factor for initial levels of depression and anxiety symptoms. Although irritability was positively related to depressive symptoms at each time point, it was not related to changes in depression. With regard to anxiety, irritability did not serve as vulnerability for changes in anxiety symptoms, but rather conditioned the effect of parenting (see above).

Summary and Conclusions

This study lends partial support to the prediction that children with temperamental vulnerabilities would be more susceptible to the effects of negative parenting. In particular, children low in effortful control reported stable or increasing symptom levels in the presence of some negative maternal behaviors (i.e. low guidance and high negativity). Further, consistent with a vulnerability model some children who exhibited temperamental vulnerabilities (e.g., high fear or low positive affect) reported higher symptoms regardless of the parenting behaviors observed (Nigg 2006). The current findings suggest that investigators should simultaneously consider that individual differences might alter children’s sensitivity to environmental influences and render them vulnerable to developing problems. Temperament may establish a range of development and may lead to the emergence of problems in isolation or through an interaction with environmental risk factors, such as parenting. Thus, fear may be exacerbated by negative parenting in predicting depression, but also represents a unique risk factor for anxiety.

These findings suggest that associations between parenting and internalizing problems may be less clear than thought (e.g., Rapee 1997) and that correspondence between parenting and child characteristics may be important (Lerner and Lerner 1994). Specifically, low autonomy granting may not be universally problematic, but rather its effect depends on children’s effortful control. Thus, the same parenting behavior may operate differently depending on the child.

Strengths and Limitations

This study had several strengths including use of a developmental framework, growth modeling, multi-method assessment, and consideration of differences in the trajectories of anxiety and depression. The sample reflected a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds within a West coast urban sample, as the flat distribution of income assured that participants from low and high-income families were equally represented. Because familial factors such as income and maternal depression may be important predictors of parenting behaviors and children’s adjustment, we accounted for the role of each of these variables in our models.

Several limitations of this study are noted. First, we only considered interactions between maternal parenting and child temperament. Fathers’ participation was not required in this study, and a single parent headed many families. Data on fathers was available for only 40% of the sample, resulting in a sample too small for parallel analyses. Second, given the low numbers in each ethnic and racial group, we could not consider potential differences across ethnicities. Third, the reliability for fear was relatively low, which might have limited estimated associations with adjustment. Fourth, a measure of maternal anxiety was not available, preventing us from considering it as a covariate. Fifth, this study used a community rather than a clinical sample. Although rates of depression and anxiety were consistent with expectations, symptom levels were generally low. Nonetheless, use of a community sample allows examination of the emergence of symptoms. Lastly, limited power prevented consideration of additional factors important in explaining these developmental trajectories (e.g., the interaction of multiple temperament dimensions or parenting behaviors).

Implications

This study begins to clarify additional factors in the development of children’s anxiety and depression by examining how temperament conditions sensitivity to parenting. Growth modeling allowed examination of a developmental model of symptom trajectories, expanding interaction effects beyond contemporaneous associations. The results suggest that models of differential responding account for some, but not all, effects, as vulnerability and goodness-of-fit models also come into play. Together these findings suggest that temperament is an important direct and moderating factor in the developmental course of depression and anxiety. Clinically, the findings highlight the importance of individual characteristics and parenting as factors that maintain or divert symptom trajectories. Further, interventions should incorporate information about temperament and help parents accommodate children’s individual differences.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research was provided by NIMH Grant #R29MH57703 awarded to Liliana Lengua and NIMH Grant #F31MH086171 awarded to Cara Kiff. The authors thank Kevin King and Robert McMahon for their valuable feedback on this manuscript and the families who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Heterogeneity of age differences through modeling age versus time in study was explored by specifying parallel models using an age-cohort design (see Mehta and West 2000). No differences emerged in the magnitude or pattern of significance of associations.

A model examining all covariates and parenting variables simultaneously was run to determine whether non-significant covariates affected any relations. The results did not differ and the reduced model was retained to preserve power (Muthén and Curran 1997).

Contributor Information

Cara J. Kiff, Email: cjkiff@uw.edu, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Box 351525, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Liliana J. Lengua, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Box 351525, Seattle, WA 98195, USA

Nicole R. Bush, Center for Health and Community, University of California, San Francisco, USA

References

- Albano AM, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Childhood anxiety disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child psychopathology. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2003. pp. 279–329. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JT. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development. 1996;67:3296–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:271–301. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandy EU, Kendall PC. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:244–255. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Plomin R. Temperament: Early developing personality traits. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Rothbart MK. Development and validation of an early adolescent temperament measure. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1992;12:153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Lochman JE, Wells KC. The moderating effects of children’s fear and activity level on relations between parenting practices and childhood symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:251–263. doi: 10.1023/a:1025704217619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam CM. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:330–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan C, Cowan P. Parenting style ratings manual. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley; 1992. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ, Willoughby MT. Testing main effects and interaction in latent curve analysis. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:220–237. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bolle M, De Fruyt F. The tripartite model in childhood and adolescence: Future directions for developmental research. Child Development Perspectives. 2010;4:174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis T. Self-regulation in preschoolers: The interplay of child approach reactivity, parenting, and control capabilities. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:84–97. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Rothbart MK. Reactive and effortful processes in the organization of temperament. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:633–652. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Hyde JS, Goldsmith HH, Van Hulle CA. Gender differences in temperament: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:33–72. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, Shaw DS. Codevelopment of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:313–333. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Rothbart MK. Contemporary instruments for assessing early temperament by questionnaire an in the laboratory. In: Strelau J, Angleitner A, editors. Explorations in temperament. New York: Plenum; 1991. pp. 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Gullone E, King NJ, Ollendick TH. Self-reported anxiety in children and adolescents: A three-year follow-up study. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2001;162:5–19. doi: 10.1080/00221320109597878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Edelsohn G, Kellam SG. A further look at the prognostic power of young children’s reports of depressed moods and feelings. Child Development. 2001;72:736–747. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE, Luxton DD. Vulnerability-stress models. In: Hankin BL, Abela JRZ, editors. Development of psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatry. 1981;46:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ. Growth in temperament and parenting as predictors of adjustment during children’s transition to adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:819–832. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Long AC. The role of emotionality and self-regulation in the appraisal-coping process: Tests of direct and moderating effects. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2002;23:471–493. [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, West SG. The additive and interactive effects of parenting and temperament in predicting adjustment problems of children of divorce. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:232–244. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner JV, Lerner RM. Explorations of the goodness-of-fit model in early adolescence. In: Carey WB, McDevitt SC, editors. Prevention and early intervention. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1994. pp. 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl MK, Malik N. Systems for coding interactions and family functioning. Coral Gables, Florida: University of Miami; 2000. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Wood JJ, Weisz JR. Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:155–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PD, West SG. Putting the individual back into individual growth curves. Psychological Methods. 2000;5:23–43. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.5.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Vannatta K, Compas BE, Vasey M, McGoron KD, Salley CG, et al. The role of coping and temperament in the adjustment of children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:1135–1143. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Sessa FM, Avenevoli S, Essex MJ. Temperamental vulnerability and negative parenting as interacting predictors of child adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:461–471. [Google Scholar]

- Muris P. The pathogenesis of childhood anxiety disorders: Considerations from a developmental psychopathology perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2006;30:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Schmidt H, Lambrichs R, Meesters C. Protective and vulnerability factors of depression in normal adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39:555–565. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, van der Pennen E, Sigmond R, Mayer B. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and aggression in non-clinical children: Relationships with self-report and performance-based measures of attention and effortful control. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2008;39:455–467. doi: 10.1007/s10578-008-0101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Curran PJ. General longitudinal modeling of individual differences in experimental designs: A latent variable framework for analysis and power estimation. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:371–402. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 4th Ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. Temperament and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:395–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordhof A, Oldehinkel AJ, Verhulst FC, Ormel J. Optimal use of multi- informant data on co-occurrence of internalizing and externalizing problems. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2008;17:174–183. doi: 10.1002/mpr.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldehinkel AJ, Veenstra R, Ormel J, de Winter AF, Verhulst FC. Temperament, parenting, and depressive symptoms in a population sample of preadolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:684–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM. Potential role of childrearing practices in the development of anxiety and depression. Child Psychology Review. 1997;17:47–67. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(96)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. What I think and feel: A revised measure of children’s manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2006. pp. 99–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The children’s behavior questionnaire. Child Development. 2001;72:1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Morris AS, Kanaya T, Steinberg L. Psychological control and autonomy granting: Opposite ends of a continuum or distinct constructs? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wachs TD. Synthesis: Promising research designs, measures, and strategies. In: Wachs TD, Plomin R, editors. Conceptualization and measurement of organism-environment interaction. Washington: American Psychological Association; 1991. pp. 162–182. [Google Scholar]