Background: Group A streptococcal pili are diverse.

Results: Mutational analyses identified a specific transpeptidase and lysine residue of the shaft protein required for pilus assembly in a serotype M6 strain.

Conclusion: Assembly and cell wall anchoring of the pili are accomplished by concerted actions of transpeptidases.

Significance: Our findings lead to predictions of homologous pilus assembly mechanisms in other species.

Keywords: Bacteria, Cell Surface Protein, Fibrillin, Protein Assembly, Protein Cross-linking, Streptococcus pyogenes, Pili, Sortase

Abstract

The human pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes produces diverse pili depending on the serotype. We investigated the assembly mechanism of FCT type 1 pili in a serotype M6 strain. The pili were found to be assembled from two precursor proteins, the backbone protein T6 and ancillary protein FctX, and anchored to the cell wall in a manner that requires both a housekeeping sortase enzyme (SrtA) and pilus-associated sortase enzyme (SrtB). SrtB is primarily required for efficient formation of the T6 and FctX complex and subsequent polymerization of T6, whereas proper anchoring of the pili to the cell wall is mainly mediated by SrtA. Because motifs essential for polymerization of pilus backbone proteins in other Gram-positive bacteria are not present in T6, we sought to identify the functional residues involved in this process. Our results showed that T6 encompasses the novel VAKS pilin motif conserved in streptococcal T6 homologues and that the lysine residue (Lys-175) within the motif and cell wall sorting signal of T6 are prerequisites for isopeptide linkage of T6 molecules. Because Lys-175 and the cell wall sorting signal of FctX are indispensable for substantial incorporation of FctX into the T6 pilus shaft, FctX is suggested to be located at the pilus tip, which was also implied by immunogold electron microscopy findings. Thus, the elaborate assembly of FCT type 1 pili is potentially organized by sortase-mediated cross-linking between sorting signals and the amino group of Lys-175 positioned in the VAKS motif of T6, thereby displaying T6 and FctX in a temporospatial manner.

Introduction

Pili are long filamentous structures that extend from the bacterial cell surface. After their discovery in a variety of pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria, multiple roles of pili in the infection process and their impact related to vaccine candidates have been reported (1, 2). In contrast to pili of Gram-negative bacteria, pilus subunits of Gram-positive bacteria are covalently attached to each other and anchored to cell wall peptidoglycans (3, 4). Typically, Gram-positive pili consist of one major and one or two minor subunits. Polymerization of the major subunit constitutes the pilus backbone shaft, whereas the minor subunits are covalently incorporated into the backbone as ancillary pilus proteins. These pilus subunits contain cell wall sorting signals (CWSSs),3 including a canonical LPXTG or LPXTG-like motif (5). Pilus subunits are assembled via this motif, i.e. polymerization of major subunits and formation of major and minor subunit complexes, and finally cross-linked to the peptidoglycan layer. These processes are mediated by a membrane-bound transpeptidase termed sortase, including a housekeeping sortase enzyme (SrtA) and pilus-associated sortase enzyme (SrtB in this study) (6–8).

The mechanism of cell wall anchoring of surface proteins governed by SrtA has been extensively investigated in Staphylococcus aureus (7). A large variety of surface proteins harboring the LPXTG motif in CWSS are recognized by SrtA. SrtA cleaves LPXTG between threonine (Thr) and glycine (Gly) residues and then makes an acyl enzyme intermediate by linking the active cysteine residue to the carboxyl group of the threonine in the motif. Subsequently, the intermediate is relieved by nucleophilic attack followed by linkage of the carboxyl group of threonine to a free amino group in the growing cell wall.

Regarding the pilus assembly, polymerization of major subunits and incorporation of minor subunits also require sortase enzymatic activity (4, 9). In many cases, the pilus-associated sortase catalyzes the formation of a peptide bond between threonine in the CWSS motif of one subunit and an ϵ-amino group of a lysine (Lys) residue conserved in a pilin motif of the other subunit (11, 12). Namely, the side chain of the lysine residue in the pilus subunit functions as a nucleophile to polymerize the major subunits and forms a complex of major and minor subunits. Thus, these intermolecular isopeptide bonds formed between pilus subunits are fundamental for pilus assembly (13–15).

Streptococcus pyogenes is a human pathogen that colonizes the mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract and epidermal layer of the skin. Consequently, S. pyogenes is responsible for a wide variety of human diseases, ranging from self-limiting purulent infections to severe necrotizing fasciitis and autoimmune diseases, such as acute rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis (16). To successfully colonize anatomical sites, S. pyogenes achieves firm attachment to host cell surfaces. Among the numerous adhesins required for tissue-specific adherence, pili have been suggested to play a central role (1, 17, 18).

The pilus genes of S. pyogenes are encoded in the FCT genomic region (loci encoding fibronectin-binding proteins, collagen-binding proteins, and T antigens) (19). Based on the variability of gene composition and sequences, this region is classified into at least nine subtypes, designated FCT types 1–9 (20, 21). Among these, pilus components of FCT type 1 are mutually distinctive from those of the other types as shown by phylogenetic analyses of both the FCT region nucleotide sequences and the amino acid sequences of backbone and ancillary pilus proteins (20, 21). In serotype M6 strains belonging to FCT type 1, the pilus-related genomic region contains genes encoding Lancefield T6 antigen, FctX, and SrtB (16, 19, 22). Mora et al. (23) showed that T6 is the major subunit of FCT type 1 pili, whereas FctX (also termed AP-1) serves as an ancillary pilus protein. The composition of FCT type 1 pili is unique because FCT types 2–8 are composed of three pilus proteins. No remarkable homology on the protein level was observed among T6, FctX, and FCT type 2/3 pilus proteins, i.e. Cpa, FctA, and FctB (21). Although the assembly mechanism and expression mode of FCT type 2/3 pili have been investigated, those of other types of pili are poorly understood (23–25).

In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time the assembly mechanism of FCT type 1 pili in a serotype M6 strain in which SrtA and SrtB were shown to collaborate to assemble pilus subunits and anchor pili to the peptidoglycan layer. We also found a lysine residue within a novel VAKS pilin motif of T6 required for T6 polymerization and incorporation of FctX at the tip of the pilus shaft. These unique characteristics of the assembly mechanism of FCT type 1 pili give insights into the complexity of the biological nature of streptococcal pili.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

The S. pyogenes serotype M6 strain TW3558 was isolated from a patient with tonsillitis (26). The Escherichia coli strain TOP10 (Invitrogen) was used as a host for derivatives of plasmids pFW5-luc, pSET4s, and pAT18 (27–29). E. coli XL10-gold (Stratagene) served as a host for plasmid pQE30 derivatives (Qiagen). All E. coli strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37 °C with agitation. The S. pyogenes wild type and isogenic mutant strains were cultured in Todd-Hewitt broth (BD Biosciences) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (BD Biosciences) (THY medium) at 37 °C in an ambient atmosphere. For selection and maintenance of mutants, antibiotics were added to the media at the following concentrations: ampicillin (Wako), 100 μg/ml for E. coli; kanamycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 μg/ml for E. coli; chloramphenicol (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μg/ml for E. coli; spectinomycin (Wako), 100 μg/ml for E. coli and 60 μg/ml for S. pyogenes; and erythromycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 150 μg/ml for E. coli and 1 μg/ml for S. pyogenes.

DNA and Computational Techniques

Purification of chromosomal DNA from S. pyogenes was done using a DNA extraction kit (Takara). Plasmid DNA was purified with a plasmid purification kit (Macherey-Nagel). Transformation of E. coli and S. pyogenes was performed as described previously (30, 31). The DNA sequence of the FCT region of strain TW3558 was determined using the reported genome sequence of MGAS10394 (GenBank accession number NC_006086) as a reference (32). The homologue of T6 was searched using the PSI-Blast algorithm. Selected amino acid sequences of the homologues (e value, <−20; coverage, >90%; identity, >80%) were aligned using ClustalW software and visualized by CLC Main workbench software (CLC bio). The signal sequence of T6 and FctX was deduced using the SignalP 3.0 server. A domain search was conducted using the SMART server.

Construction of Recombinant Vectors and Mutant Strains of S. pyogenes

The construction of in-frame deletion mutants was conducted using a temperature-sensitive shuttle vector, pSET4s, as reported previously (33, 34). The summarized procedure is depicted in supplemental Fig. S1. During the course of construction, a merodiploid strain was created after the first allelic replacement and then resolved to possess either mutant or wild type alleles after the second allelic replacement. To rule out the effects of secondary mutations that may have arisen during mutagenesis, a clone possessing the wild type allele was also used as a revertant strain in this study. Both an in-frame deletion mutant and a revertant strain arose from the same merodiploid ancestor. The correct in-frame deletion of genes was confirmed by site-specific PCR and sequence analyses of the chromosomal locus encompassing the recombination sites. All primers used are listed in supplemental Table S1.

For the construction of the fctX operon-luc reporter strain, the 3′-end of the operon was amplified with PCR using primers FctXOpe-LucF and FctXOpe-LucR (supplemental Table S1) and cloned into multiple cloning site I of a luciferase reporter plasmid, pFW5-luc, via the NheI/BamHI sites. The resulting plasmid was integrated into the chromosome of strain TW3558. Correct chromosomal integration of the luciferase gene was confirmed by site-specific PCR.

To generate mutated tee6, an overlapping PCR strategy was used with the primers listed in supplemental Table S2. The mutated fragment was cloned into the streptococcal shuttle vector pAT18-PgyrA (24). Introduction of the mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Wild type tee6 was also cloned into pAT18-PgyrA. The resultant plasmids were transformed into the tee6 in-frame deletion mutant (Δtee6) and grown in the presence of erythromycin.

To create an fctX expression vector, the fctX gene, including the putative promoter, was amplified using primers 3558OpF and 3558FctXR (supplemental Table S3) and Phusion hot start DNA polymerase (Finnzymes). The PCR product was cloned into pDONR221 (Invitrogen) using a BP recombination reaction. Then, utilizing an LR recombination reaction, the fctX gene fragment was cloned into pAT18-ccdB in which a blunt-ended cassette containing attR sites flanking the ccdB gene and the chloramphenicol resistance gene (Invitrogen) was inserted into the SmaI site of pAT18 according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mutant fctX fragment was created by overlapping PCR using primers 3558OpF and 3558FctXR as well as the primers with mutations listed in supplemental Table S3. The fragment was also cloned into pAT18-ccdB. Correct introduction of the mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing. These constructs were transformed into the in-frame fctX deletion mutant (ΔfctX). The procedures are briefly depicted in supplemental Fig. S2.

Preparation of Antisera against T6 and FctX

Recombinant T6 and FctX proteins were prepared as described before (24). Briefly, recombinant proteins were hyperexpressed in E. coli cells and purified from E. coli lysates using a QIAexpress protein purification system (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Eluted proteins were dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 5.4 mm Na2HPO4, 1.8 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.4), and the concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific).

Mouse antisera against FctX and T6 were raised by immunizing BALB/c mice with the purified recombinant proteins as described before (24). Rabbit antiserum against FctX was raised by immunizing male New Zealand White rabbits with purified recombinant FctX proteins. Briefly, the rabbits were vaccinated intradermally with a mixture of 400 μg of recombinant proteins and complete Freund adjuvant (Difco) followed by four boosts with 200 μg of recombinant proteins with incomplete Freund adjuvant (Difco) at 2-week intervals. The antiserum was purified for the immunogold labeling of FctX as described previously (35).

Extraction of Cell wall and Supernatant Fractions and Preparation for Immunoblotting

S. pyogenes strains were grown to the late exponential phase or overnight in THY medium and washed twice with PBS. The cells were suspended in protoplasting buffer (0.1 m KPO4, pH 6.2, 40% sucrose, 10 mm MgCl2) containing Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science) and 250 μg/ml N-acetylmuramidase (Seikagaku Biobusiness), and then incubation was performed for 3 h at 37 °C. The resulting protoplasts were sedimented by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min, and the resultant supernatants were subjected to immunoblot analyses as cell wall fractions.

Total proteins in the culture supernatants were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid on ice for 1 h followed by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min. The pellets were washed twice with ice-cold ethanol and resuspended in 1 m Tris buffer, pH 8.0.

The proteins of each fraction were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using 3–10% acrylamide gels (Wako) and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with casein-based blocking reagent (Snow Brand), incubated for 1 h with mouse antisera diluted 1:2,000 in PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20 (PBST), washed three times with PBST, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Cell signaling) diluted 1:2,000 in PBST for 1 h. Following washing steps, the membranes were developed with Pierce Western blotting substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Immunoprecipitation

The cell wall fraction of the wild type strain was prepared as noted above. The fraction was then dialyzed against PBS and incubated with rabbit anti-FctX antiserum or non-immune rabbit serum at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, protein G-coated magnetic beads (Invitrogen) were added to the mixture (10%, v/v) and incubated at 4 °C for 5 h. The beads were extensively washed with PBST five times and resuspended in SDS-containing sample buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 1% SDS, 0.1% bromphenol blue, 10% glycerol) containing 0.1 m dithiothreitol followed by boiling for 5 min and brief centrifugation. The resultant supernatant samples were subjected to immunoblot analysis using mouse anti-T6 antiserum and non-immune mouse serum.

RT-PCR

A total RNA sample was prepared from the wild type strain grown to the late exponential phase (36). Synthesis of cDNA from total RNA was conducted with a Transcripter high fidelity cDNA synthesis kit (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The possibility of DNA contamination was excluded by PCR analysis with non-RT samples. All primers used are listed in supplemental Table S1. The RT-PCR amplifications were performed using Ex Taq (Takara).

Quantitative Assays for Luciferase Activity

An fctX operon-luc reporter strain was cultured in THY medium at 37 °C. To measure luminescence, aliquots from bacterial cultures were withdrawn at 30-min intervals and processed as described previously (37), using d-luciferin (Wako) and a GloMax 20/20n luminometer (Promega).

Immunogold Electron Microscopy

Immunogold labeling of whole bacteria was conducted as described previously with a minor modification (38). Wild type and isogenic mutant strains were grown to the midexponential phase (A600=0.5), then washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in PBS. A drop of bacterial suspension was placed onto carbon-coated Formvar-covered nickel grids (Pyser-SGI) and allowed to settle for 15 min. Bacteria on the grids were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde (Wako) for 5 min at room temperature and incubated with blocking buffer (PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 100 μg/ml human Fc fragment (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 1 h at room temperature. Pili were labeled with polyclonal mouse or rabbit antisera diluted 1:10 with PBS containing 10% (v/v) blocking buffer for 1 h followed by washing five times with PBS. Subsequently, the grids were incubated with 15- or 20-nm gold-conjugated secondary antibodies (BB International) diluted 1:20 in PBS containing 10% (v/v) blocking buffer. After washing steps with PBS and distilled water, the grids were air-dried. Gold-labeled pilus proteins were observed with an H-7650 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi) at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

RESULTS

FCT Type 1 Pilus Genes Are Transcribed as Operon

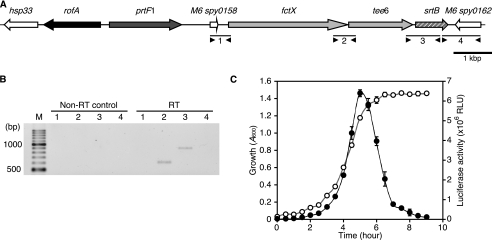

To gain insight into the genetic features of the FCT type 1 pilus region, we first performed transcriptional analysis of the region using serotype M6 strain TW3558, hereafter referred to as WT. The pilus region of the strain contains the tee6, fctX, and srtB genes encoding T6, FctX, and SrtB, respectively. These genes are located in tandem between the M6 spy0158 and M6 spy0162 genes (Fig. 1A). To analyze whether these contiguous genes are transcribed in a polycistronic manner, RT-PCR analysis was performed using four sets of primers designed to amplify the boundaries of each gene (Fig. 1A, four pairs of arrowheads). Amplicons between fctX and tee6 as well as tee6 and srtB were detected in the PCRs using cDNA of WT as a template, whereas the regions between M6 spy0158 and fctX and between srtB and M6 spy0162 were not amplified (Fig. 1B). In addition, no amplicon was detected in the non-RT control samples. Because the putative transcriptional terminator located downstream of both the M6 spy0158 and srtB genes was present (data not shown), it is most likely that the fctX, tee6, and srtB genes are transcribed in a polycistronic manner as an operon (referred to as fctX operon).

FIGURE 1.

Transcriptional analysis of FCT type 1 pilus region of serotype M6 strain. A, shown is a genetic map from serotype M6 strain TW3558. Gene designations are presented above each arrow. The M6 spy numbers were assigned according to the corresponding genes in the M6 genome sequence (strain MGAS10394, GenBank accession number NC_006086). Black arrow, transcriptional regulator rofA; dark gray arrow, fibronectin-binding protein prtF1; light gray arrow, pilus proteins tee6 and fctX; light gray hatched arrow, pilus region-associated sortase srtB; white arrow, heat shock protein, putative transposase, and hypothetical protein. B, RT-PCR analysis of the pilus region. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA recovered from a late exponential phase culture of a wild type strain. Total RNA subjected to the same reaction without reverse transcriptase (Non-RT) served as a negative control of PCRs. Four sets of primers (shown as arrowheads in A) were used to amplify fragments 1–4 (shown as bars in A). The PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on 1.5% Tris borate-EDTA agarose gels and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. The numbers for each lane correspond to the expected PCR fragments 1–4. The DNA marker size is indicated on the left. M, 100-bp ladder DNA marker. C, temporal transcriptional activity of fctX operon. Luciferase activities (black circles) and culture densities (white circles) of the fctX operon-luc strain were determined. Luciferase activity is represented as relative light units (RLU). Three experiments were performed with data from a representative experiment shown. Values are presented as the mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples. Error bars represent S.D.

To analyze the temporal transcription profile of the fctX operon, a luciferase gene reporter fusion system was used to determine temporal activities (Fig. 1C). After 5 h in a batch culture reaching the late exponential phase, the fctX operon-luc construct demonstrated a sharp peak in luciferase activity. Our data indicated that FCT type 1 pilus genes are transcribed at the maximum amount in the late exponential phase.

Roles of T6, FctX, and SrtB in Assembly of FCT Type 1 Pili

As a first step toward understanding the mechanism by which FCT type 1 pili are assembled, we sought to clarify the roles of T6, FctX, and SrtB in that process. Because the corresponding genes were shown to be transcribed in a polycistronic manner, markerless in-frame deletion mutants and revertant strains were constructed to avoid polar effects on the expression of neighboring genes. The growth rates of all constructed mutants were similar to that of WT (data not shown).

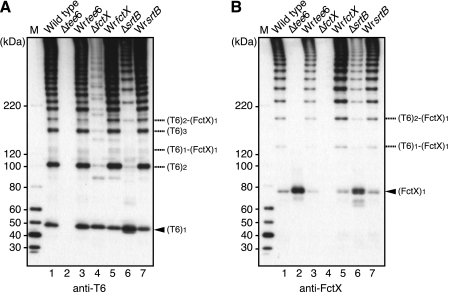

Cell wall fractions of WT and the mutant strains were immunoblotted with anti-T6 and anti-FctX antisera (Fig. 2). In the cell wall fraction of WT and all revertant strains, high molecular weight ladder bands (HLBs) reflecting polymerization of T6 and the incorporation of FctX into T6 were detected with both anti-T6 and FctX antisera on immunoblots (Fig. 2, A and B). Furthermore, formation of the T6 and FctX complex was substantiated by results of immunoprecipitation assays (supplemental Fig. S3). The bands corresponding to the monomeric forms of T6 and FctX with a molecular mass of ∼50 and 70–80 kDa, respectively, were also detected (Fig. 2, A and B, arrowheads). The deduced molecular mass of FctX without a signal sequence and cell wall sorting signal is ∼108 kDa, thus, the 70–80-kDa band detected in the blot with anti-FctX antisera may correspond to either the breakdown product or a protease-cleaved product of FctX (Fig. 2B). In contrast, in the cell wall fraction of Δtee6, HLBs completely disappeared, and the monomeric form of FctX was clearly detected, indicating that T6 is the shaft protein and that FctX is the ancillary protein of pili (Fig. 2B, lane 2). On the other hand, the intensity of the HLBs was decreased, and the migration pattern changed with deletion of fctX (Fig. 2A, lane 4), which suggests that FctX is required for efficient polymerization of T6. The bands detected below those representing the (T6)n homopolymer might have been the proteolytic products of (T6)n. The intensity of the HLBs also decreased, and the pattern changed in the cell wall fraction of the srtB deletion mutant (ΔsrtB; Fig. 2, A and B, lane 6). However, the pattern of HLBs of ΔsrtB did not coincide with that of ΔfctX, indicating that all HLBs of ΔsrtB reflect the T6 and FctX complex, (T6)n-(FctX)1, based on molecular mass sizes. Of note, pilus assembly was not stopped even in the absence of SrtB.

FIGURE 2.

Immunoblot analyses of T6 and FctX in cell wall extracts from wild type and mutants of FCT type1 pilus region genes. Total proteins in the cell wall fraction of the wild type and its derivatives were subjected to immunoblotting with mouse antisera against T6 (A) and FctX (B). Lane 1, wild type; lane 2, tee6 deletion mutant (Δtee6); lane 3, tee6 revertant (Wrtee6); lane 4, fctX deletion mutant (ΔfctX); lane 5, fctX revertant (WrfctX); lane 6, srtB deletion mutant (ΔsrtB); lane 7, srtB revertant (WrsrtB). The position of monomeric forms of T6 and FctX is indicated by an arrowhead. The deduced positions of the complex forms of T6 and FctX are indicated on the right. The protein marker sizes are indicated on the left. M, protein size marker.

Both SrtA and SrtB Are Required for Efficient Assembly and Cell Wall Anchoring of FCT Type 1 Pili

Because the polymerization of T6 and incorporation of FctX into T6 were not abolished by srtB deletion, we investigated the possible involvement of the housekeeping sortase SrtA in pilus assembly. Mutant strains with srtA (ΔsrtA) deletion and srtA/srtB double deletion (ΔsrtA/srtB) were constructed. For double knock-out of the srtA and srtB genes, a deletion of srtB was introduced into ΔsrtA. Therefore, the genotype of the revertant strain (designated WrsrtB/ΔsrtA in Fig. 3) was the same as that of ΔsrtA.

FIGURE 3.

Both SrtA and SrtB are required for assembly and cell wall anchoring of FCT type1 pili. Total protein in cell wall fractions (A and B) and culture supernatants (C and D) of S. pyogenes strain TW3558 and its sortase mutants was subjected to immunoblotting with mouse antisera against T6 (A and C) and FctX (B and D). Lane 1, wild type; lane 2, srtB deletion mutant (ΔsrtB); lane 3, srtB revertant (WrsrtB); lane 4, srtA deletion mutant (ΔsrtA); lane 5, srtA revertant strain (WrsrtA); lane 6, srtA/srtB deletion mutant (ΔsrtA/srtB); lane 7, srtB revertant strain in the background of srtA/srtB deletion mutant (WrsrtB/ΔsrtA). The positions of monomeric forms of T6 and FctX are indicated by arrowheads. The deduced positions of the complex forms of T6 and FctX are indicated on the right. The sizes of the molecular mass standards are indicated on the left. M, protein size marker.

Cell wall and culture supernatant fractions were prepared from these mutants, including ΔsrtB and its revertant strain, and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-T6 and anti-FctX antisera (Fig. 3, A and B). HLBs that reacted with both antisera were still present in the cell wall fraction of ΔsrtA; however, the signal intensity was remarkably decreased as compared with that of WT (Fig. 3, A and B, lane 1 versus lane 4). Of note, HLBs were readily detected in the culture supernatant of ΔsrtA and WrsrtB/ΔsrtA (Fig. 3, C and D, lanes 4 and 7), which strongly indicates that SrtA mainly functions in the final anchoring of pili to the cell wall. Because a lower level of T6 monomer was detected in both fractions of ΔsrtA, it can be speculated that T6 polymerization in ΔsrtA is more efficient than in WT. When both srtA and srtB were deleted, no HLB was detected in the cell wall fraction (Fig. 3, A and B, lane 6). Taken together, these findings indicate that SrtB is primarily required for T6 polymerization and the complex formation of T6 and FctX. However, in ΔsrtB, SrtA can compensate to a certain extent for the role of SrtB in formation of that complex and T6 polymerization. In contrast, SrtA apparently plays a central role in cell wall anchoring of assembled pili. Hence, the functions of both sortases are distinctive during the course of pilus assembly.

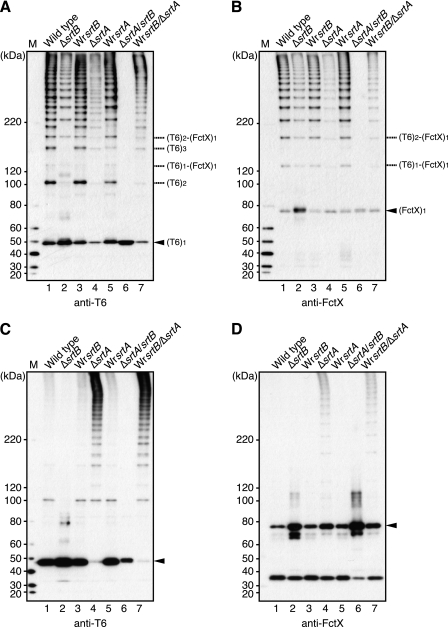

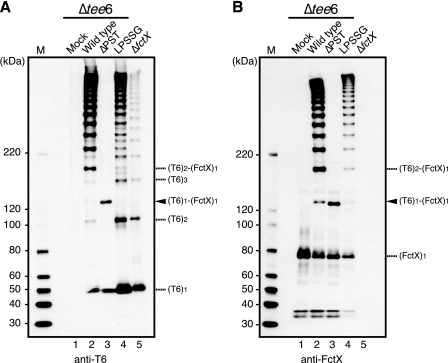

LPSTG Motif of T6 Is Not Required for Formation of T6 and FctX Complex

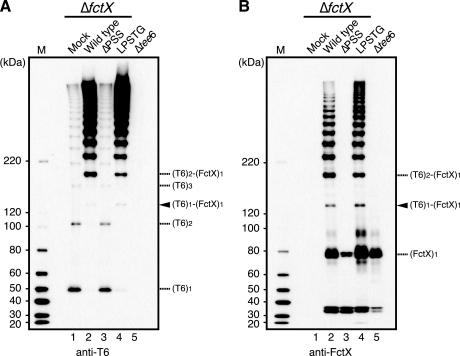

As shown in Fig. 3, SrtB is primarily required for T6 polymerization and formation of the T6 and FctX complex. To verify whether the LPSTG motif in the CWSS of T6, which might be processed by sortase enzymes, is necessary for T6 polymerization and complex formation, we introduced a mutation into this motif and investigated the effect on pilus assembly. Mutated tee6 in which the canonical LPSTG motif was replaced with LG was expressed in Δtee6 using a shuttle vector (ΔPST), whereas the vector harboring wild type tee6 and an empty vector were also transformed and used as controls (wild type and mock, respectively). In the cell wall extract of the wild type, HLBs detected with anti-T6 and anti-FctX antisera were visible in immunoblots (Fig. 4, A and B, lane 2). In contrast, HLBs were not detected in the fractions of mock and ΔPST (Fig. 4, A and B, lanes 1 and 3). In addition, no HLBs were detected in the concentrated culture supernatant of the ΔPST mutant (supplemental Fig. S4, lane 11), indicating that the LPSTG motif is essential for T6 polymerization.

FIGURE 4.

Introduction of mutation into LPSTG motif of T6 abrogated T6 polymerization but had no effect on heterodimer formation of T6 and FctX. Cell wall fractions were extracted from a tee6 deletion mutant (Δtee6) transformed with an empty shuttle vector (mock; lane 1) or a shuttle vector harboring wild type tee6 (lane 2) or mutated tee6. In mutated tee6, the LPSTG motif of T6 was replaced with either LG (ΔPST; lane 3) or LPSSG (lane 4). These extracts were subjected to immunoblotting with mouse antisera against T6 (A) and FctX (B). The fraction of the fctX deletion mutant transformed with an empty shuttle vector (ΔfctX; lane 5) served as a control. The position of the heterodimer composed of T6 and FctX is denoted by an arrowhead. The deduced positions of the monomeric and complex forms of T6 and FctX are indicated on the right. The molecular mass sizes of the protein marker (M) are indicated on the left.

Despite the lack of HLBs in the cell wall extract of the ΔPST mutant, a band with a molecular mass of ∼130 kDa was visible (Fig. 4, A and B, lane 3, arrowheads). Because this 130-kDa band, which reacted with both anti-T6 and anti-FctX antisera, was not visible in the extracts of the fctX deletion mutant transformed with an empty vector (ΔfctX) or mock (Fig. 4, A and B, lanes 1 and 5) and a band with the same molecular mass was also detected in the immunoprecipitation assay (supplemental Fig. S3), it was identified as a heterodimer band, which reflects the complex of T6 and FctX, (T6)1-(FctX)1. Therefore, we concluded that the LPSTG motif of T6 is not necessary for formation of isopeptide bonds between T6 and FctX proteins.

The ∼120-kDa band detected with anti-FctX antiserum, but not with anti-T6 antiserum, in supernatant fractions may represent released intact FctX monomers (supplemental Figs. S4, lanes 9–16, and S5, lanes 10–12 and 14–16). We consider that the prominent ∼180-kDa band detected with both anti-T6 and -FctX antisera in the supernatant fraction of the ΔPST mutant is most likely the heterodimer of T6 and intact FctX (supplemental Fig. S4, lane 11).

When the canonical LPSTG motif of T6 was replaced with the analogous LPSSG motif present in FctX, the intensity of bands representing (T6)n was increased and that of those representing (T6)n-(FctX)1 was decreased in the cell wall fraction as compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 4, A and B, lane 2 versus lane 4). In contrast, HLBs were detected more clearly in the culture supernatant of the mutant (supplemental Fig. S4, A and B, lane 10 versus lane 12). These findings indicated that the introduced LPSSG sequence in T6 drives T6 homopolymerization and is not suitable for cell wall anchoring of pili. When wild type tee6 or mutated tee6 genes were expressed in Δtee6ΔsrtB, HLBs and the heterodimer band completely disappeared in both the cell wall and culture supernatant fractions (supplemental Fig. S4), indicating a principal role of SrtB in complex formation and subsequent T6 polymerization.

LPSSG Motif of FctX Is Required for Formation of T6 and FctX Complex

The sorting signal of FctX includes an LPXTG-like motif, i.e. LPSSG, which is likely recognized by sortases. To determine whether the LPSSG motif in CWSS of FctX functions in formation of the complex, either wild type fctX or mutated fctX in which the LPSSG motif was replaced with LG was expressed in ΔfctX (wild type and ΔPSS, respectively), and the cell wall fractions of these mutants were immunoblotted with anti-T6 and anti-FctX antisera (Fig. 5). In the cell wall extract of ΔfctX transformed with an empty vector (mock), the intensity of HLBs as detected with anti-T6 antiserum was decreased and the migration pattern changed as compared with those of the wild type (Fig. 5A, lane 1 versus lane 2). The same was observed with the extract of ΔPSS (Fig. 5A, lane 3). The heterodimer band was virtually undetected in the cell wall extracts as well as the concentrated culture supernatants of ΔPSS mutant, mock, and Δtee6 transformed with an empty vector (Fig. 5, lanes 1, 3, and 5 and supplemental Figs. S5, lanes 9 and 11, and S4, lane 9). Thus, the LPSSG motif of FctX is suggested to be essential for isopeptide bonds between FctX and T6 proteins. On the basis of data obtained thus far, we also assumed that FctX is located at the tip of the T6 polymer.

FIGURE 5.

Introduction of mutation into LPSSG motif of FctX abrogated heterodimer formation of T6 and FctX. Cell wall fractions were extracted from an fctX deletion mutant (ΔfctX) transformed with an empty shuttle vector (mock; lane 1) or a shuttle vector harboring wild type fctX (lane 2) or mutated fctX. In mutated fctX, the LPSSG motif of FctX was replaced with either LG (ΔPSS; lane 3) or LPSTG (lane 4). These extracts were subjected to immunoblotting with mouse antisera against T6 (A) and FctX (B). The fraction of the tee6 deletion mutant transformed with an empty shuttle vector (Δtee6; lane 5) served as a control. The position of the heterodimer composed of T6 and FctX is denoted by an arrowhead. The deduced positions of the monomer and complex forms of T6 and FctX are indicated on the right. The sizes of the molecular mass standards are indicated on the left. M, protein size marker.

When the canonical LPSSG motif of FctX was substituted with the LPSTG motif, HLBs detected in the cell wall fraction representing (T6)n-(FctX)1 were shifted to a slightly higher position (Fig. 5, lane 2 versus lane 4). In the culture supernatant fractions, HLBs detected in the LPSTG mutant also had higher molecular weights (supplemental Fig. S5, lanes 10 and 12), indicating that T6 polymerization was more efficient in the FctX LPSTG mutant. It is most likely that the complex of T6 and FctX was formed more efficiently in the LPSTG mutant, possibly accelerating the polymerization of T6. When wild type or mutated fctX genes were expressed in ΔfctXΔsrtB, HLBs and the heterodimer band completely disappeared in both the cell wall and culture supernatant fractions (supplemental Fig. S5), which again suggests a principal role of SrtB in pilus assembly.

Lysine Residue 175 of T6 Is Essential for T6 Polymerization

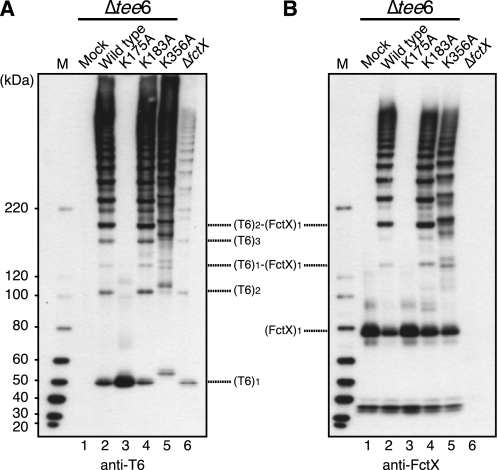

To identify the lysine residues of T6 that play a critical role in pilus assembly, the amino acid sequences of T6 and its homologues were aligned (supplemental Fig. S6). Selected homologues included the recently identified Streptococcus suis pilus subunit (39), T6 counterparts in serotype M23 and M24 S. pyogenes strains, and homologous proteins present in Clostridium perfringens, Ruminococcus obeum, and Eubacterium ventriosum. Twenty-two Lys residues, which are well conserved among homologues, especially in streptococci, and located between the putative signal peptidase cleavage site and LPSTG motif, were selected for point mutation analysis, i.e. Lys-35, Lys-42, Lys-56, Lys-103, Lys-175, Lys-183, Lys-194, Lys-195, Lys-216, Lys-221, Lys-268, Lys-321, Lys-331, Lys-341, Lys-345, Lys-356, Lys-404, Lys-407, Lys-410, Lys-476, Lys-494, and Lys-512. We replaced each lysine residue with alanine and expressed either wild type tee6 or a series of mutated tee6 on a background of Δtee6 (wild type, and mutants referred to as K35A for example).

Cell wall extracts of each mutant strain were subjected to Western blot analysis. HLBs detected with anti-T6 antiserum were visible for all point mutated strains except for K175A (Fig. 6A, lane 3, and supplemental Fig. S7, left panel, lane 7). Because the monomeric form of K175A with a molecular mass of ∼52 kDa was readily detected, the mutant protein was precisely expressed, and disappearance of HLBs was not due to protein instability. Moreover, HLBs were not detected in the concentrated culture supernatant of the K175A mutant (data not shown). Accordingly, Lys-175 in T6 is suggested to participate in the formation of intramolecular isopeptide bonds between T6 pilin subunits. Among the streptococcal homologues of T6, the VAKS amino acid sequence, including Lys-175, is conserved (supplemental Fig. S6); thus, the sequence VAKS was designated as the FCT type 1 pilin motif.

FIGURE 6.

Conserved lysine residue of T6 required for T6 polymerization and heterodimer formation of T6 and FctX. Cell wall fractions were extracted from the tee6 deletion mutant (Δtee6) transformed with an empty shuttle vector (mock; lane 1) or with a shuttle vector harboring wild type tee6 (lane 2) or mutated tee6 (K175A, K183A, and K356A; lanes 3, 4, and 5, respectively) in which Lys residues Lys-175, Lys-183, and Lys-356 were point mutated with alanine (Ala) residue. The fraction of an fctX deletion mutant transformed with an empty shuttle vector (ΔfctX; lane 6) served as a control. These extracts were subjected to immunoblotting with mouse antisera against T6 (A) and FctX (B). The deduced positions of the monomer and complex forms of T6 and FctX are indicated on the right. The sizes of the molecular mass standards are indicated on the left. M, protein size marker.

It is noteworthy that both the monomeric and polymeric forms of K356A migrated slower than those of wild type T6 (Fig. 6, A and B, lane 5, and supplemental Fig. S7, right panel, lane 6). Because lysine residues are also involved in intramolecular isopeptide bonds in many pilus proteins (15), it is quite possible that T6 also contains intramolecular bonds and that Lys-356 participates in bond formation.

Involvement of Lys-175 in Formation of T6 and FctX Complex

To identify the lysine residue of T6 crucial for incorporation of FctX, the formation of the T6 and FctX complex was examined by immunoblotting using cell wall extracts of the wild type; a series of T6 mutant strains, including K175A, K183A, and K356A; and empty vector-transformed Δtee6 (mock). The (T6)1-(FctX)1 heterodimer band with a molecular mass of ∼130 kDa was detected in the cell wall extracts of the wild type and T6 mutants K183A and K356A (Fig. 6, lanes 2, 4, and 5). However, the heterodimer band was not detected in the mock or K175A mutant (Fig. 6, lane 3). Thus, Lys-175 of T6 is also suggested to be responsible for cross-linking between T6 and FctX proteins.

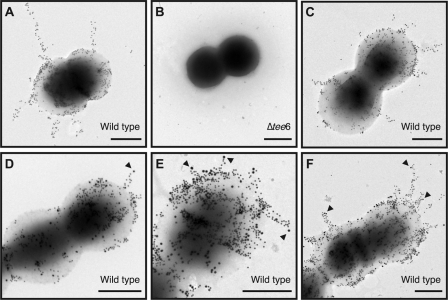

Localization of FctX in T6 Pilus Shaft

To visualize T6 pili and the position of FctX in T6 pili, immunogold electron microscopy analysis was performed using whole bacteria. First, we labeled T6 in WT with anti-T6 mouse polyclonal antiserum and a secondary anti-mouse IgG conjugated with 15-nm gold particles. Δtee6 was used as a negative control. As expected, WT produced abundant T6 pili, which protruded circumferentially from the cell surface (Fig. 7A). In contrast, no gold-labeled pili were observed in Δtee6 (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Immunogold labeling of T6 and FctX. A and B, a wild type strain (A) and tee6 deletion mutant (B) were incubated with anti-T6 antiserum followed by incubation with 15-nm gold-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. Bar, 0.5 μm. C, T6 of the wild type strain was labeled with 15-nm gold particles as noted above followed by incubation with non-immune rabbit serum and a 20-nm gold-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG. Bar, 0.5 μm. D, E, and F, T6 of the wild type strain was labeled with 15-nm gold particles as noted above. Subsequently, FctX was labeled with rabbit anti-FctX antiserum and 20-nm gold-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG. FctX observed at the tip of T6 pilus shaft is shown by arrowheads. Bar, 0.5 μm.

Next, double labeling of T6 and FctX in WT was conducted to examine the location of FctX. T6 was labeled with 15-nm gold particles in the same manner described above, whereas FctX was detected using anti-FctX rabbit polyclonal antiserum and a secondary anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with 20-nm gold particles. As a negative control of FctX labeling after T6 labeling, non-immune rabbit serum and an anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with 20-nm gold particles were utilized. With this negative control, nonspecific 20-nm gold particles were sparsely detected only on the cell surface (Fig. 7C). In contrast, although the majority of FctX labeled with larger gold particles was detected on the cell surface, labeled FctX was occasionally observed on the tips of T6 shafts labeled with smaller 15-nm gold particles (Fig. 7, D, E, and F), indicating the localization of FctX at the tip of T6 shafts, which is implied by previous immunoblot data. Based on our findings, we propose an assembly model of FCT type 1 pili (Fig. 8 and see “Discussion”).

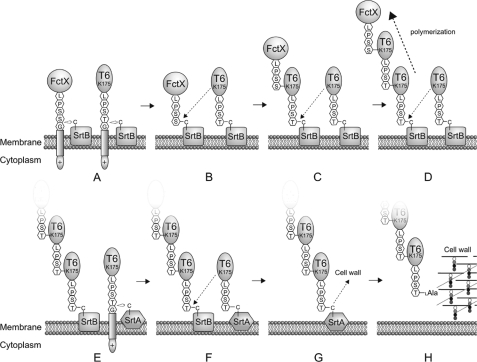

FIGURE 8.

Proposed model of assembly of FCT type1 pili based on present and previous findings. Pilus-associated sortase SrtB cleaves the LPSSG motif of FctX between serine and glycine residues (A); this is accompanied by formation of an acyl enzyme intermediate. SrtB also forms an intermediate with T6 (A). FctX is further transferred to an ϵ-amino group of a lysine residue of T6 (Lys-175) by nucleophilic attack (B). The complex of FctX and T6 is then transferred to Lys-175 of T6 (C). Consequently, T6 polymerizes, and FctX becomes localized at the tip of the T6 pilus shaft (D). For cell wall anchoring of pili, the housekeeping sortase SrtA cleaves the LPSTG motif of T6 between the threonine and glycine residues (E) and forms an acyl enzyme intermediate (F). Finally, the pili are covalently linked to a free amino group of the peptidoglycan layer (G).

DISCUSSION

Among the various adhesins that mediate firm attachment to host human tissues and tropism for specific infection sites by S. pyogenes, the pilus has become the center of attention in explorations of the initial step of infection (1, 40). The variability of S. pyogenes pili on both the gene and protein levels is outstanding among streptococcal species, which is reflected by the fact that the antigenicity of pilus proteins is one of the determinants for T serotyping (20, 23, 24, 41). To reveal the involvement of S. pyogenes pili in the infection mechanism and tissue tropism, detailed analyses of functions, assembly mechanisms, and the expression mode are crucial. Although molecular characterizations of FCT type 2 and 3 pili have been reported, characterizations of other types of pili remain elusive (23–25). To begin molecular characterization of thus far uncharacterized pili, we focused on the assembly mechanism of FCT type 1 pili in a serotype M6 strain.

For assembly of pili in Gram-positive bacteria, pilus subunits are covalently linked to each other by the action of a transpeptidase enzyme called sortase. In a serotype M6 strain, two sortase enzymes are encoded in the genome, i.e. the housekeeping sortase SrtA and pilus region-associated sortase SrtB (8). The present findings demonstrated that SrtB is required for this assembly, and SrtA can partially compensate in the absence of SrtB. Therefore, it is most likely that both recognize LPSTG and LPSSG motifs buried in the CWSSs of T6 and FctX, respectively. Based on ambiguous data obtained with swapping of the motif, there may be a sequence preference for each sortase, and we speculate that SrtA prefers the canonical LPSTG sequence as compared with the LPSSG sequence. Because the assembly of FCT type 1 pili was scarcely influenced by deletion of the srtA gene, it is reasonable to speculate that SrtB primarily mediates heterodimer formation and subsequent T6 polymerization. On the other hand, deletion of the srtA gene caused a greater release of pili into the culture supernatant; thus, SrtA might function mainly for cell wall anchoring of pili as has been reported for many different types of pili (42–44). Therefore, designation of the complex or monomer pilus proteins toward the amino group of either cell wall or pilus proteins would be determined by the availability of SrtA and SrtB, which is likely regulated by the expression mode of the srtA gene and fctX operon.

An unexpected finding in this study is that SrtA may have an ability to generate the complex and polymerize T6 in certain conditions. Immunoblot data for the cell wall fraction extracted from the srtB deletion mutant showed that all detected HLBs represented the (FctX)1-linked T6 polymer based on molecular mass size, i.e. (T6)n-(FctX)1, which suggests that T6 polymerizations without the linkage of FctX do not occur solely by the action of SrtA. In other words, SrtA has the ability to polymerize T6 when FctX is covalently linked to T6. Moreover, because no HLBs were detected when pilus genes were expressed ectopically in the background of srtB deletion, the assembly by SrtA might require temporospatial regulation of the expression of pilus genes. Because the ability of the housekeeping sortase to polymerize pilus major subunits has not been reported, the unique interaction between SrtA and the (T6)1-(FctX)1 complex is expected to change the present understanding of its conventional functions.

Another unexpected finding is that deletion of fctX caused a decreased intensity of HBLs in immunoblotting, which indicates that FctX is required for proper polymerization of T6. The same finding was recently reported in a study of S. suis pili (39). Although there is no experimental data to explain the phenomenon, it can be speculated that the heterodimer formation of FctX and T6 accelerates polymerization of T6. In FCT type2/3 pili, the signal peptidase I homologue SipA/LepA encoded in the pilus region may function as a chaperone (24, 45). Such a chaperone-like function of FctX may serve as a trigger factor activity in serotype M6 strains that encode no SipA/LepA counterparts in the FCT type 1 pilus region.

Our findings revealed that a lysine residue (Lys-175) and the LPSTG motif of T6 are simultaneously necessary to polymerize T6. Lysine residues in major subunits of pili from other species, including SpaA of Corynebacterium diphtheriae, FctA of FCT type 2 pili, RrgB of Streptococcus pneumoniae, and BcpA of Bacillus cereus, are known to function as nucleophiles to polymerize major subunits (11, 13, 14, 46). Because a conserved pilin motif, YPKN, reported in C. diphtheriae and B. cereus (44), was not present in T6, we searched the T6-specific pilin motif, including the lysine residue, using point mutation analysis and sequence alignment of T6 and its homologues identified by a Blast search. Surprisingly, the VAKS motif designated FCT type 1 pilin motif was well conserved among T6 and its streptococcal homologues, including confirmed or inferred major subunits of S. suis and Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus (data not shown). Thus, the lysine residue corresponding to Lys-175 of T6 present in the VAKS motif could be involved in the polymerization of their major subunits. Because homologues of T6 and FctX are found in zoonotic streptococcal pathogens, it is quite possible that the FCT type 1 pilus region was horizontally transferred among streptococcal species, which is also supported by the fact that the gene upstream of fctX encodes a transposon remnant (19).

We also revealed that Lys-175 of T6 participates not only in T6 polymerization but also in the linkage of T6 and FctX. Introduction of the mutation into the LPSSG motif in the CWSS of FctX hampered the linkage; thus, it is most likely that sortases cleave the motif between serine and glycine residues, and then the carboxyl group of the serine residue is covalently linked to Lys-175 of T6, thereby forming the complex of T6 and FctX. A similar case has been reported regarding the interaction between Cpa and FctA from FCT type 3 pili in a serotype M3 strain (25). It is possible that the mechanism in which the same lysine residue links major subunits and major/minor subunits is common in Streptococcus species.

Intramolecular isopeptide bonds formed between lysine and asparagine residues have also been revealed by recent crystallographic and mass spectral analyses of several major pilus subunits, including FctA in the FCT type 2 pili, BcpA in B. cereus, SpaA in C. diphtheriae, and RrgB in S. pneumoniae (10, 13, 14, 46). The position of intramolecular isopeptide bonds differs among those pilus proteins. In our point mutation study, immunoblotting results showed that the migration pattern of K356A was considerably altered. Such a change was also reported in another study in which a mutation was introduced into the lysine residue responsible for the intramolecular bonds of FctA (25). Therefore, Lys-356 of T6 could be involved in potential intramolecular isopeptide bonds. Although the mutation did not affect polymerization, it is possible that the deduced isopeptide bond formed via Lys-356 contributes to thermostability and resistance against unfolding stress and proteolysis as reported for FctA (15).

According to a previous report by Barnett and Scott (8), cell wall anchoring of T6 is exclusively mediated by SrtB, whereas knock-out of SrtA has no effect on that anchoring in a serotype M6 laboratory strain. However, the present study revealed that the anchoring of T6 is mainly mediated by the action of SrtA. This discrepancy may be attributable to differences in experimental design, including mutation strategy (insertional mutagenesis versus in-frame deletion), the antisera utilized against T6 (typing serum versus T6- and FctX-specific), and detection methods (whole cell dot blot assay versus immunoblot analysis of cell wall fractions).

Based on the present findings and the currently accepted model of sortase function, we propose a three-step model of surface display of FCT type 1 pili (Fig. 8). First, FctX and T6 form a complex. Next, T6 monomers polymerize to constitute the pilus shaft and allow FctX to be localized at the tip of the shaft. Finally, the assembled pilus is covalently anchored to the cell wall. Synthesized T6 and FctX in the cytoplasm are guided to the cell membrane via a Sec-dependent secretion pathway. Then, the LPSSG motif in CWSS of FctX and the LPSTG motif in CWSS of T6 are recognized and processed by SrtB, and acyl enzyme intermediates are formed. Subsequently, FctX is transferred to an ϵ-amino group of Lys-175 of T6 by nucleophilic attack, thereby forming the complex of monomeric T6 and FctX. The T6-FctX heterodimer is then transferred to an ϵ-amino group of the Lys-175 of neighboring T6. Repeated nucleophilic attack between the T6-FctX complex and the side chain of monomeric T6 results in polymerization of T6 and positioning of FctX at the tip of the T6 shaft (Fig. 8).

Because deletion of srtB did not abolish T6 polymerization or the complex formation of T6 and FctX, these processes may also occur at a low frequency by individual actions of SrtA that are independent of SrtB. Of note, our immunoblot data showed that T6 also polymerized without incorporation of FctX. For cell wall anchoring of FCT type 1 pili, SrtA cleaves the LPSTG motif of T6 at the base of the pilus structure and then forms an acyl enzyme intermediate. Finally, the assembled pilus is transferred to a free amino group of the cell wall (Fig. 8). For the anchoring step, SrtA rather than SrtB plays a central role. Thus, FCT type 1 pili are elaborately assembled and anchored to the cell wall by the concerted actions of SrtA and SrtB.

In summary, we revealed differential roles of SrtA and SrtB in the assembly and cell wall anchoring of FCT type 1 pili. We also found that the lysine residue in the VAKS pilin motif of T6 is involved in intramolecular isopeptide bonds of T6 and formation of the T6 and FctX complex. In addition, FctX was shown to be located at the tip of the T6 pilus shaft. Although the biological importance of FCT type 1 pili remains elusive, pilus proteins positioned away from the cell surface and capsule might function for the first interaction with the human host. Because homologous pili are potentially produced by zoonotic streptococcal pathogens, future investigation of the structure and functions of FCT type 1 pili will provide insights into the universal interactions between streptococcal pili and the host.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge T. Sekizaki (University of Tokyo) and D. Takamatsu (National Institute of Animal Health) for providing the pSET4s plasmid. pAT18 was kindly provided by P. Trieu-Cuot (Institut Pasteur). We also thank J. Yamauchi for helpful technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (B) 20390465 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas 18073011; Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research for Young Scientists (A) 2189048; and Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research for Young Scientists (B) 19791343, 20791336, and 21791786 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7 and Tables S1–S3.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) AB669020.

- CWSS

- cell wall sorting signal

- HLB

- high molecular weight ladder band.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kreikemeyer B., Gámez G., Margarit I., Giard J. C., Hammerschmidt S., Hartke A., Podbielski A. (2011) Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 301, 240–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Telford J. L., Barocchi M. A., Margarit I., Rappuoli R., Grandi G. (2006) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 509–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Proft T., Baker E. N. (2009) Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 66, 613–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scott J. R., Zähner D. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 62, 320–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schneewind O., Model P., Fischetti V. A. (1992) Cell 70, 267–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mandlik A., Swierczynski A., Das A., Ton-That H. (2008) Trends Microbiol. 16, 33–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marraffini L. A., Dedent A. C., Schneewind O. (2006) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 192–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barnett T. C., Scott J. R. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 184, 2181–2191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hendrickx A. P., Budzik J. M., Oh S. Y., Schneewind O. (2011) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 166–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Budzik J. M., Poor C. B., Faull K. F., Whitelegge J. P., He C., Schneewind O. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 19992–19997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Budzik J. M., Marraffini L. A., Souda P., Whitelegge J. P., Faull K. F., Schneewind O. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10215–10220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ton-That H., Schneewind O. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 50, 1429–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kang H. J., Coulibaly F., Clow F., Proft T., Baker E. N. (2007) Science 318, 1625–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kang H. J., Paterson N. G., Gaspar A. H., Ton-That H., Baker E. N. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16967–16971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kang H. J., Middleditch M., Proft T., Baker E. N. (2009) Biopolymers 91, 1126–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cunningham M. W. (2000) Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13, 470–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abbot E. L., Smith W. D., Siou G. P., Chiriboga C., Smith R. J., Wilson J. A., Hirst B. H., Kehoe M. A. (2007) Cell. Microbiol. 9, 1822–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Manetti A. G., Zingaretti C., Falugi F., Capo S., Bombaci M., Bagnoli F., Gambellini G., Bensi G., Mora M., Edwards A. M., Musser J. M., Graviss E. A., Telford J. L., Grandi G., Margarit I. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 64, 968–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bessen D. E., Kalia A. (2002) Infect. Immun. 70, 1159–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Falugi F., Zingaretti C., Pinto V., Mariani M., Amodeo L., Manetti A. G., Capo S., Musser J. M., Orefici G., Margarit I., Telford J. L., Grandi G., Mora M. (2008) J. Infect. Dis. 198, 1834–1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kratovac Z., Manoharan A., Luo F., Lizano S., Bessen D. E. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189, 1299–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schneewind O., Jones K. F., Fischetti V. A. (1990) J. Bacteriol. 172, 3310–3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mora M., Bensi G., Capo S., Falugi F., Zingaretti C., Manetti A. G., Maggi T., Taddei A. R., Grandi G., Telford J. L. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15641–15646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nakata M., Köller T., Moritz K., Ribardo D., Jonas L., McIver K. S., Sumitomo T., Terao Y., Kawabata S., Podbielski A., Kreikemeyer B. (2009) Infect. Immun. 77, 32–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Quigley B. R., Zähner D., Hatkoff M., Thanassi D. G., Scott J. R. (2009) Mol. Microbiol. 72, 1379–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Murakami J., Kawabata S., Terao Y., Kikuchi K., Totsuka K., Tamaru A., Katsukawa C., Moriya K., Nakagawa I., Morisaki I., Hamada S. (2002) Epidemiol. Infect. 128, 397–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Podbielski A., Spellerberg B., Woischnik M., Pohl B., Lütticken R. (1996) Gene 177, 137–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takamatsu D., Osaki M., Sekizaki T. (2001) Plasmid 46, 140–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trieu-Cuot P., Carlier C., Poyart-Salmeron C., Courvalin P. (1991) Gene 102, 99–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Inoue H., Nojima H., Okayama H. (1990) Gene 96, 23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Caparon M. G., Scott J. R. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 204, 556–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Banks D. J., Porcella S. F., Barbian K. D., Beres S. B., Philips L. E., Voyich J. M., DeLeo F. R., Martin J. M., Somerville G. A., Musser J. M. (2004) J. Infect. Dis. 190, 727–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Okahashi N., Nakata M., Sakurai A., Terao Y., Hoshino T., Yamaguchi M., Isoda R., Sumitomo T., Nakano K., Kawabata S., Ooshima T. (2010) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 1192–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sumitomo T., Nakata M., Higashino M., Jin Y., Terao Y., Fujinaga Y., Kawabata S. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2750–2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kreikemeyer B., Nakata M., Oehmcke S., Gschwendtner C., Normann J., Podbielski A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33228–33239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakata M., Podbielski A., Kreikemeyer B. (2005) Mol. Microbiol. 57, 786–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Podbielski A., Woischnik M., Leonard B. A., Schmidt K. H. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 31, 1051–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Okahashi N, Nakata M., Terao Y., Isoda R., Sakurai A., Sumitomo T., Yamaguchi M., Kimura R. K., Oiki E., Kawabata S., Ooshima T. (2011) Microb. Pathog. 50, 148–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Okura M., Osaki M., Fittipaldi N., Gottschalk M., Sekizaki T., Takamatsu D. (2011) J. Bacteriol. 193, 822–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bessen D. E., Lizano S. (2010) Future Microbiol. 5, 623–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Griffith F. (1934) J. Hygiene 34, 542–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Budzik J. M., Marraffini L. A., Schneewind O. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 66, 495–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nobbs A. H., Rosini R., Rinaudo C. D., Maione D., Grandi G., Telford J. L. (2008) Infect. Immun. 76, 3550–3560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Swaminathan A., Mandlik A., Swierczynski A., Gaspar A., Das A., Ton-That H. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 66, 961–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zähner D., Scott J. R. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190, 527–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Spraggon G., Koesema E., Scarselli M., Malito E., Biagini M., Norais N., Emolo C., Barocchi M. A., Giusti F., Hilleringmann M., Rappuoli R., Lesley S., Covacci A., Masignani V., Ferlenghi I. (2010) PLoS One 5, e10919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]