Background: Coordinate regulation by kinases and 14-3-3 proteins regulates sodium transport through phosphorylation and inhibition of E3 ligases.

Results: Phosphorylation at similar but distinct target motifs can either inhibit or stabilize E3 ligases.

Conclusion: E3 ligases integrate multiple kinase inputs to regulate sodium transport and protein stability.

Significance: These findings broaden our knowledge of how E3 ligases and sodium transport are regulated by phosphorylation.

Keywords: E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, ENaC, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Phosphorylation, Protein Stability, 14-3-3, Nedd4-2, SGK1

Abstract

Regulation of epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC)-mediated transport in the distal nephron is a critical determinant of blood pressure in humans. Aldosterone via serum and glucocorticoid kinase 1 (SGK1) stimulates ENaC by phosphorylation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2, which induces interaction with 14-3-3 proteins. However, the mechanisms of SGK1- and 14-3-3-mediated regulation of Nedd4-2 are unclear. There are three canonical SGK1 target sites on Nedd4-2 that overlap phosphorylation-dependent 14-3-3 interaction motifs. Two of these are termed “minor,” and one is termed “major,” based on weak or strong binding to 14-3-3 proteins, respectively. By mass spectrometry, we found that aldosterone significantly stimulates phosphorylation of a minor, relative to the major, 14-3-3 binding site on Nedd4-2. Phosphorylation-deficient minor site Nedd4-2 mutants bound less 14-3-3 than did wild-type (WT) Nedd4-2, and minor site Nedd4-2 mutations were sufficient to inhibit SGK1 stimulation of ENaC cell surface expression. As measured by pulse-chase and cycloheximide chase assays, a major binding site Nedd4-2 mutant had a shorter cellular half-life than WT Nedd4-2, but this property was not dependent on binding to 14-3-3. Additionally, a dimerization-deficient 14-3-3ϵ mutant failed to bind Nedd4-2. We conclude that whereas phosphorylation at the Nedd4-2 major site is important for interaction with 14-3-3 dimers, minor site phosphorylation by SGK1 may be the relevant molecular switch that stabilizes Nedd4-2 interaction with 14-3-3 and thus promotes ENaC cell surface expression. We also propose that major site phosphorylation promotes cellular Nedd4-2 protein stability, which potentially represents a novel form of regulation for turnover of E3 ubiquitin ligases.

Introduction

Nedd4-2,2 a member of the homology to the E6-associated protein C terminus (HECT) family of E3 ubiquitin ligases (1, 2), is a physiologically important regulator of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) (1, 3). ENaC comprises α, β, and γ subunits and reabsorbs Na+ across several epithelia, including the distal nephron (4). Nedd4-2 is a potent inhibitor of ENaC activity in vivo. Liddle syndrome, a severe form of inherited hypertension, results from mutations in ENaC that abolish interaction with Nedd4-2 and thus cause renal Na+ retention (5, 6). Moreover, Nedd4-2 knock-out mice have salt-sensitive hypertension (7). In cultured cells Nedd4-2 ligase activity decreases ENaC cell surface expression and Na+ current (8). Potential effects of Nedd4-2-mediated ENaC ubiquitination include increased endocytosis from the plasma membrane and enhanced proteasomal and/or lysosomal degradation (9, 10). Furthermore, Nedd4-2 may decrease ENaC open probability by limiting ENaC cell surface residence time and thus proteolytic cleavage of its α and γ subunits (11).

Phosphorylation is an important mechanism for the regulation of Nedd4-2 and other E3 ligases. For example, AMP-activated protein kinase and others negatively regulate ENaC through stimulatory phosphorylation of Nedd4-2, which enhances ENaC interaction or Nedd4-2 ubiquitin ligase activity (12, 13). Conversely, serum and glucocorticoid kinase 1 (SGK1) and protein kinase A (PKA) can positively regulate ENaC through inhibitory phosphorylation of Nedd4-2 at three canonical sites. Alanine mutations at these three sites diminish SGK1 and PKA-stimulated ENaC cell surface expression and activity (1, 14). SGK1 and/or PKA-mediated Nedd4-2 phosphorylation-dependent interaction with 14-3-3 scaffolding proteins prevents subsequent interaction with and ubiquitination of ENaC (15–17). Aldosterone stimulates SGK1 expression, whereas vasopressin activates PKA. Therefore, Nedd4-2 is a convergence point for hormonal regulation of epithelial Na+ transport in the distal nephron.

The mechanisms of aldosterone-mediated regulation of Nedd4-2 by 14-3-3 are poorly characterized. In general, 14-3-3 proteins bind as dimers to phosphorylated ligands (e.g. Nedd4-2) at one high affinity (major) site, which facilitates the interaction with a lower affinity (minor) site (18). 14-3-3 proteins propagate kinase-dependent signaling events by regulating their target proteins via several mechanisms, including activity, subcellular localization, and/or stability. Alanine substitution at either minor (Ser-338, Thr-363) or major (Ser-444) sites on Nedd4-2 (Xenopus numbering) disrupt SGK1 stimulation of ENaC (1, 14, 15). Also, abrogation of binding to phosphorylated Ser-444 via a S444A mutant or Ser(P)-444 antibody decreases binding of Nedd4-2 to 14-3-3 (15–17). However, in heterologous expression systems we have reported that SGK1-dependent enhancement of Nedd4-2 phosphorylation at Ser-338 (>4.5-fold) and Thr-363 (>40-fold) is substantially greater than at Ser-444 (1.5-fold) (13). Moreover, we and others have observed a high level of basal phosphorylation at Ser-444 in cells (13, 19). These findings suggest that this residue may not be the principal regulatory site of aldosterone-dependent stimulation of ENaC.

We have identified a significant role for Nedd4-2 minor site phosphorylation as a trigger for enhanced interaction with 14-3-3 and thus aldosterone-mediated ENaC stimulation. Our data also suggest that basal major site phosphorylation, which also participates in interaction with dimeric 14-3-3, is important for regulating the cellular stability of Nedd4-2.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies

A rabbit polyclonal antibody recognizing the WW2 domain of Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 (Millipore) was used for immunoprecipitation of endogenous Nedd4-2, and a rabbit polyclonal Nedd4-2 antibody (Abcam) was used for immunoblotting. Rabbit serum against Ser(P)-328 of mouse Nedd4-2 (equivalent to Ser-444 of Xenopus Nedd4-2 (xNedd4-2) was a gift from Jon Loffing (University of Zurich) (19). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used for detection of endogenous SGK1 (Sigma), E-cadherin (Sigma), and 14-3-3 proteins (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Commercial antibodies against epitope tags were also used: HA (Roche Applied Science), FLAG (Sigma), and GFP (Clontech; to detect EYFP), and 1D4 (Millipore).

DNA Constructs

All FLAG-tagged xNedd4-2 cDNAs and constitutively active mouse SGK1 (S422D) were subcloned into a modified pcDNA3 vector (pMO) using PCR-directed mutagenesis. An HA-tagged dimerization-deficient mutant was created using site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange; Stratagene) of the following mouse 14-3-3ϵ amino acids: E5K, LAE12,13,14QQR, Y85Q, M88N, and E90Q, adapted from Tvizion et al. (20). EYFP-tagged R18WT (wild-type) or R18M (mutant) were gifts from Haian Fu (Emory University) (21). All mutants and constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Cell Culture

Human embryonic kidney (HEK-293T) cells and mouse polarized kidney cortical collecting duct (mpkCCDc14) cells were maintained and cultured as described previously (15).

Co-immunoprecipitation of Endogenous Nedd4-2

mpkCCDc14 cells were plated on collagen-coated 1.0-cm2 Transwells (Corning Costar) at superconfluent density. When monolayers reached a transepithelial resistance >1000 ohm-cm2 (22), cells were incubated in serum-free, supplement-free medium for 24 h prior to treatment. Following treatment for 3 h with ethanol (vehicle) or 1 μm aldosterone (Sigma), cells were lysed in 150 μl of lysis buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mm EDTA, 0.4% deoxycholate acid, and 1% Nonidet P-40) containing protease inhibitors (1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mm, benzamidine, and 1× Complete Protease Inhibitor Mixture (Roche Applied Science)) and phosphatase inhibitors (25 mm sodium fluoride, 2 μm microcystin-LR, and 1× Phosphatase-Inhibitor Mixture Sets I and II (Calbiochem)). Immunoprecipitation was performed overnight with anti-Nedd4 antibody and protein A-agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) with gentle rocking at 4 °C. Controls for immunoprecipitation were performed using a concentration of normal IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) equivalent to that of the primary precipitating antibody. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue or transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblotting.

Relative Quantitation of Nedd4-2 Phosphorylation Sites by Mass Spectrometry

The band containing Nedd4-2 was excised from a Coomassie-stained gel (see Co-immunoprecipitation section, above), followed by in-gel digestion with trypsin and addition of acrylamide as the alkylating agent as described previously (23), with the addition of Protease Max (Promega) for increased peptide recovery and shorter digestion times. Extracted peptides were dried in a SpeedVac to completion. Prior to analysis, a fraction of the peptide pool was reconstituted using 97.8% water, 2% acetonitrile, 0.2% formic acid and injected onto a self-packed fused silica 150-μm inner diameter C18 column. The LC was an Eksigent nano2D LC, run at 600 nl/min. The LC gradient was either 60 or 80 min, linear from 2% mobile phase B to 35% mobile phase B followed by a ramp to 65% mobile phase B. The eluate was nanoelectrosprayed using a Michrom Advance source (Auburn) into an LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer (MS) (Thermo Fisher), which was set on data-dependent acquisition mode, sequencing using HCD and/or CAD the top eight most intense ions of charge state 2+ or greater. The. RAW files were converted offline to mzXML format using a msconvert script and searched using a Sorcerer work station with a Sequest search engine. The static modification was Cys propionamide, and variable modifications were Met oxidation and Ser, Thr, or Tyr phosphorylation. The searched results were uploaded into a Scaffold viewer for easier visualization. For relative quantitation of changes in phosphorylation stoichiometry, the ratio of the intensity of peaks in extracted ion chromatograms of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated versions of the same peptides acquired by MS were compared. The identified nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated peptides encompassing residues equivalent to Ser-338, Thr-363, and Ser-444 were then synthesized in vitro (Anaspec) and used for determination of absolute quantitation of endogenous Nedd4-2.

Absolute Quantitation of Nedd4-2 Phosphorylation Sites by Mass Spectrometry

Enzymatic digests of Nedd4-2 were separated by LC-MS/MS using an Agilent 1100 HPLC system. Samples (10 μl) were injected in duplicate onto a reverse phase column (Kinetex C18, 50 × 2.1 mm, 2.6-μm particle size, 100-Å pore size; Phenomenex). Components were eluted at 25 °C at a flow rate of 250 nl/min. The gradient HPLC method consisted of the following: 5% B, 0–0.3 min, linear ramp to 35% B at 6 min and to 60% B at 7 min, followed by ramp back to 10% B at 7.5 min and reequilibration at 10% B for 2.5 min, for a total run time of 10 min. Mobile phases were: A = 0.1% formic acid in water (v/v); and B = 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (v/v). The LC eluate was introduced into the MS ion source without splitting. A Quattro Premier triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters-Micromass) equipped with a standard electrospray ion source was used for detection. The MS was operated with a capillary voltage of 3.5 kV, source temperature of 120 °C, desolvation temperature of 350 °C, and collision gas (argon) pressure of 2.8 × 10−3 mbar. Positive ion selected reaction monitor mode was used for monitoring the transitions of ions for each analyte (supplemental Table 1).

The lower limit of quantitation, defined as 10:1 signal-to-noise ratio for the analytes varied (supplemental Table 1). Standard calibration curves were obtained over the concentration range 0.0025–2 pmol/μl. A 13C-5/15N-valine-labeled peptide corresponding to nonphosphorylated Ser-338 was spiked into each sample and calibration curve solutions at 1 μm and served as an internal standard. Instrumentation control and data analyses were accomplished using MassLynx 4.1 and QuanLynx 4.1 software (Waters-Micromass).

Co-immunoprecipitation of Nedd4-2 and 14-3-3 in HEK-293T Cells

Cells were transiently transfected as indicated with FLAG-tagged Nedd4-2, SGK1 S422D, HA-tagged 14-3-3ϵ, EYFP-tagged R18 peptide, and as described previously (13). Immunoprecipitation was performed with M2 anti-FLAG (Sigma) or anti-HA (Roche Applied Science) antibody conjugated to resin, and samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG or anti-HA-horseradish peroxidase 3F10. Endogenous 14-3-3 isoforms were detected with anti-pan-14-3-3 (K-19) antibody. Scanning densitometry was measured using ImageJ software, and values for immunoprecipitated 14-3-3 were normalized to Nedd4-2 within the same lane.

ENaC Surface Biotinylation Assay

HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with α (HA-tagged), β, and γ subunits of mouse ENaC, FLAG-Nedd4-2, and SGK1. Two days after transfection, cells were washed with modified (M)-PBS (Invitrogen D-PBS with 1 mm MgCl2 and CaCl2 (pH 7.8)), and then cell surface proteins were labeled with 0.5 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-biotin (Pierce) in M-PBS for 30 min on ice and then quenched with 100 mm glycine in M-PBS for 10 min at 4 °C. After washing three times with M-PBS, cells were lysed in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (0.4% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 63 mm EDTA, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8), and protease inhibitors). Biotinylated (cell surface) and interacting proteins were isolated by incubating cell lysate with immobilized NeutrAvidin beads (Pierce) overnight with gentle rocking at 4 °C. Following separation by SDS-PAGE, biotinylated HA-tagged α ENaC was detected by immunoblotting and quantified by scanning densitometry. Anti-pan-cadherin antibody was used as a loading control for cell surface proteins.

Pulse-Chase Assays

HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with 1 μg of WT or mutant FLAG-tagged Nedd4-2 (3 μg for S444A mutant) constructs with 1 μg of EYFP-tagged WT or mutant R18 peptide. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were starved in cysteine- and methionine-free modified Eagle's medium (MEM) for 30 min and then radiolabeled with 0.05 mCi/ml Tran35S-label (MP Biomedicals) for 15 min. Cells were chased in serum-free MEM at 37 °C for 0 to 8 h. At the appropriate chase time, cells were rinsed twice with PBS and lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.15 m NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. FLAG-Nedd4-2 was immunoprecipitated using M2 anti-FLAG antibody coupled to protein A/G beads (Pierce), as described previously (13). Immunoprecipitated FLAG-Nedd4-2 was resolved by SDS-PAGE, and dried gels were analyzed using a PhosphorImager (Bio-Rad). The detected bands were quantitated using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). For experiments with S444A Nedd4-2, values for each time point were fitted to an exponential decay curve using IGOR-Pro 4.0 software (WaveMetrics), and half-life values were calculated from the decay constant obtained from each fitted curve. The relative protein amount (N(t)) at each time point was modeled as N(t) = N0·exp(−t/τ), where N0 is the protein amount at time 0, and inverse tau (1/τ) is the time constant. Half-life (t½) values were calculated as t½= τ·ln2.

Cycloheximide Chase Assays

HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with 0.4 μg of WT or mutant FLAG-tagged Nedd4-2 (0.8 μg for S444A mutant) constructs with 0.4 μg of WT or mutant R18. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with 100 μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and then chased at 37 °C for 0 to 8 h. At the appropriate chase time, cells were rinsed twice with cold PBS and lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG-HRP. The detected bands were then quantitated using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). For S444A Nedd4-2, relative values for each time point were fitted to an exponential decay curve as described above for pulse-chase assays.

Statistical Analysis

Data were obtained from experiments performed three to five times, and values are presented as mean ± S.E. p values were calculated by analysis of variance or Student's t test as appropriate. A p value of <0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Aldosterone Induces Significant Nedd4-2 Phosphorylation at a Minor Relative to the Major Site

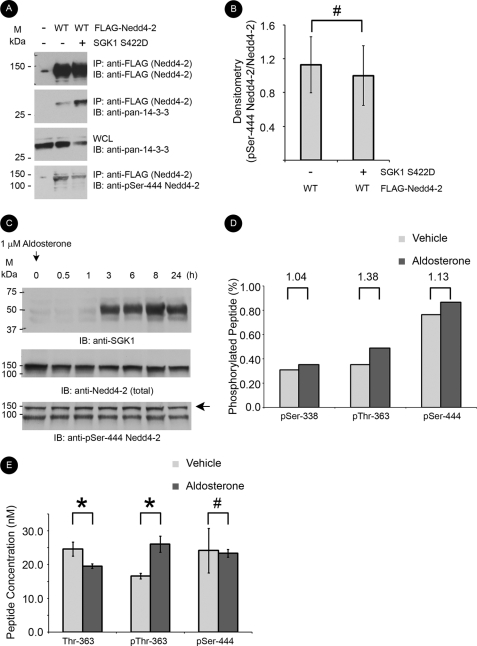

We first tested whether constitutively active SGK1 (S422D) phosphorylates heterologously expressed Nedd4-2 in HEK-293T cells. Although increased 14-3-3 binding to immunoprecipitated Nedd4-2 occurred with co-expression of SGK1, there was no appreciable increase in phosphorylation of the Ser-444 residue in Nedd4-2 under these conditions, as assayed by a phospho-specific antibody generated against the major 14-3-3 binding site on Nedd4-2 (Fig. 1, A and B). We then examined an aldosterone-stimulated time course of major site phosphorylation of endogenous Nedd4-2 in mpkCCDc14 cells. Despite a robust increase in SGK1 expression starting at 3 h, we were unable to detect a significant increase in phosphorylation at Ser-444 at any time point from 0 to 24 h (Fig. 1C). To measure the ratio of phosphorylated residues in endogenous Nedd4-2 obtained from mpkCCDc14 cell lysates, we analyzed Nedd4-2 protein using LC-MS/MS and compared the peak intensity of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated peptides (Fig. 1D and supplemental Fig. 1). After treatment of mpkCCDc14 cells with vehicle for 3 h, the major site was phosphorylated (76%). By relative quantitation, there was only a modest 13% increase in major site phosphorylation with aldosterone treatment.

FIGURE 1.

Evaluation of major and minor site phosphorylation of Nedd4-2. A, FLAG-Nedd4-2 and SGK1 S422D constructs co-expressed and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG beads. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies. Representative blots from the immunoprecipitation (IP) and whole cell lysate (WCL) are shown (n = 3). B, densitometry of Ser(P)-444 band intensity normalized to immunoprecipitated Nedd4-2 (#, p > 0.05 for the indicated comparisons; n = 4). C, immunoblot analysis of SGK1, total Nedd4-2, and Ser-444 phosphorylation (arrow) in aldosterone-treated mpkCCDc14 cell lysates. mpkCCDc14 cells were grown to high resistance on permeable supports and then treated with 1 μm aldosterone for the indicated time intervals. A representative blot is shown (n = 3). D, relative quantitation analysis of Nedd4-2 peptides by mass spectrometry using LC-MS/MS. Ratio of phosphorylated peptide to total nonphosphorylated plus phosphorylated peptide (percentage) for each of the three described SGK1 phosphorylation sites (Ser-338, Thr-363, and Ser-444) under different conditions. mpkCCDc14 cells were treated with vehicle (100% ethanol) (light bars) or 1 μm aldosterone (dark bars) for 3 h prior to harvest of Nedd4-2. Value above each peptide indicates intensity ratio of aldosterone to vehicle. E, absolute quantitation of Nedd4-2 peptides by mass spectrometry using LC-MS/MS and internal peptide standards. Samples treated with vehicle (light bars) or aldosterone (dark bars) are grouped by the indicated Nedd4-2 peptide. Neither peptide with Ser-338 or nonphosphorylated Ser-444 were consistently detected above the lower limit of quantitation using this method and thus are not shown (*, p < 0.05; #, p = 0.46; n = 3). Designation of major and minor sites is based on predicted affinity of 14-3-3 binding at each individual site. Phosphorylated residues are numbered according to Xenopus Nedd4-2, but are conserved from Xenopus to mouse to human.

We performed an additional absolute quantitation analysis using LC-MS/MS and peptide standards to measure more precisely the amount of major site phosphorylation (supplemental Fig. 1). Using this approach (Fig. 1E) there was no significant increase in major site phosphorylation in the presence versus absence of aldosterone treatment (23.4 ± 1.1 versus 24.2 ± 6.6 nm, respectively). Nonphosphorylated peptides encompassing this residue were not consistently found above the lower limit of quantitation. However, Thr-363, one of the two minor 14-3-3 binding sites in Nedd4-2, was more phosphorylated with aldosterone treatment versus vehicle in both relative (38% increase) and absolute (26.1 ± 2.4 versus 16.6 ± 0.8 nm, respectively) quantitation assays. As further confirmation, nonphosphorylated peptides at Thr-363 decreased in aldosterone versus vehicle-treated samples (19.6 ± 0.7 versus 24.7 +/2.1 nm, respectively). Ser-338, the other minor site, was not more phosphorylated in aldosterone- versus vehicle-treated samples. Neither nonphosphorylated nor phosphorylated peptides surrounding Ser-338 were detectable by our absolute quantitation method due to poor ionization efficiency (supplemental Table 1). Taken together, the major site of Nedd4-2 is phosphorylated at base line and does not significantly increase with SGK1 co-transfection or aldosterone treatment. In contrast, phosphorylation at the Thr-363 minor site is significantly and relatively further enhanced in aldosterone-treated mpkCCDc14 cells. We focused on the role of the minor sites to understand better the mechanisms of aldosterone-stimulated inhibition of Nedd4-2.

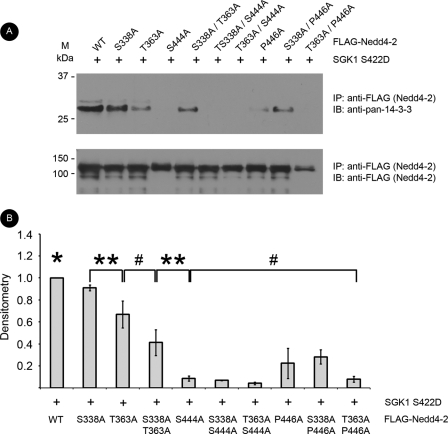

Phosphorylation-deficient Mutants of Nedd4-2 at Minor Sites Decrease Interaction with 14-3-3 Proteins

In co-immunoprecipitation experiments from HEK-293T cells transfected with SGK1 and either WT or mutant Nedd4-2 (S338A, T363A, or S338A/T363A), we found that interaction with endogenous 14-3-3 proteins was decreased (by 9 ± 3%, 33 ± 12%, and 59 ± 12%, respectively) with mutant Nedd4-2 expression relative to that with WT Nedd4-2 expression (Fig. 2). T363A Nedd4-2 decreased interaction with 14-3-3 more than S338A. A double minor site Nedd4-2 mutant (S338A/T363A) did not significantly decrease 14-3-3 interaction further compared with T363A Nedd4-2 alone. The major site Nedd4-2 mutants (S444A and P446A, which diminishes 14-3-3 binding without disrupting phosphorylation at Ser-444) (15) also showed markedly diminished binding compared with WT Nedd4-2 (by 92 ± 2% and 78 ± 14%, respectively) (Fig. 2). The remaining double mutants, each of which included a minor site mutation, did not exhibit significantly different binding to 14-3-3 than did their corresponding single major site mutants. Taken together, the major site is critical, but the minor sites are also important for interaction with 14-3-3. We next tested the roles of these Nedd4-2 mutants to alter cell surface ENaC expression.

FIGURE 2.

Minor site mutants of Nedd4-2 decrease interaction with 14-3-3. FLAG-Nedd4-2 constructs and SGK1 S422D were co-expressed and immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG beads. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-FLAG or anti-14-3-3 antibodies. A, representative blots from the immunoprecipitation. B, densitometry of 14-3-3 band intensity normalized to immunoprecipitated Nedd4-2 (*, p < 0.05 for WT versus all other conditions; **, p < 0.05 and #, p > 0.05 for the indicated comparisons; n = 4).

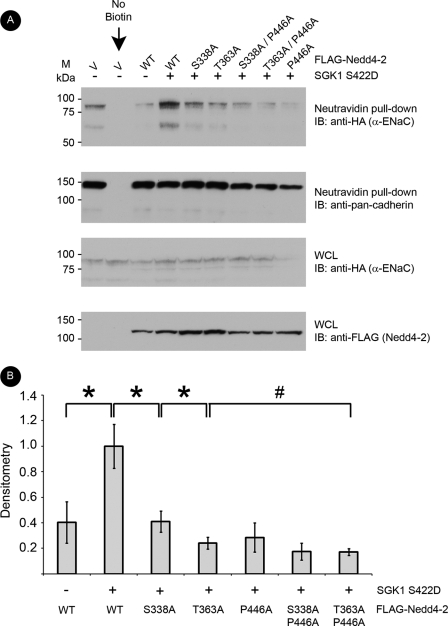

SGK1 Does Not Augment Cell Surface ENaC in the Presence of Minor Site Mutants of Nedd-2

In surface biotinylation assays of HEK-293T cells co-transfected with α-, β-, and γ-ENaC, SGK1, and WT or mutant Nedd4-2, we first confirmed that cell surface expression of α-ENaC was decreased when co-expressed with WT Nedd4-2, but restored with added SGK1 (Fig. 3A, first four lanes), as described previously (24). In the presence of SGK1, compared with WT Nedd4-2 co-expression, Nedd4-2 harboring Ala mutations at Ser-338 or Thr-363 decreased cell surface α-ENaC (by 59 ± 8% and 76 ± 5%, respectively) (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the greater inhibitory effect of the T363A mutation on the binding of 14-3-3 to Nedd4-2 (Fig. 2), the Nedd4-2 T363A mutant more strongly attenuated cell surface α-ENaC expression compared with the S338A mutant. The ability of SGK1 to enhance α-ENaC surface expression in the presence of Nedd4-2 was also attenuated with inclusion of major site Nedd4-2 mutants (e.g. by 71% ± 11% with the P446A mutant), but not significantly more than T363A Nedd4-2 alone (Fig. 3B). In summary, mutations at minor sites were sufficient to attenuate SGK1-induced cell surface expression of α-ENaC significantly.

FIGURE 3.

Minor site mutants of Nedd4-2 decrease cell surface expression of α-ENaC. FLAG-Nedd4-2 constructs, SGK1 S422D, and αβγ-ENaC (HA-α-ENaC) were transfected into HEK-293T cells and surface proteins labeled by biotinylation for subsequent affinity purification with neutravidin-linked beads. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies. E-cadherin was probed as a surface protein loading control. A, representative blots from the pulldown and whole cell lysates (WCL). B, densitometry of cell surface α-ENaC (cleaved + uncleaved band intensity) normalized to α-ENaC in the whole cell lysate (*, p < 0.05 and #, p > 0.05 for the indicated comparisons; n = 4).

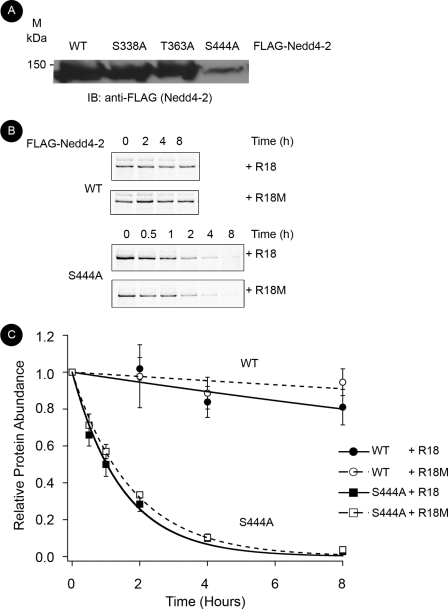

Phosphorylation at the Major Site Is Important for Nedd4-2 Protein Stability

We next examined the role for phosphorylation at the major site. We consistently observed that, despite transfection with three times as much plasmid DNA, steady-state expression of S444A Nedd4-2 in HEK-293T cells was substantially decreased compared with that of WT and minor site mutants HEK-293T (Fig. 4A). Thus, we studied whether major site phosphorylation is important for Nedd4-2 cellular stability. Using [35S]Met/Cys labeling of newly synthesized proteins and pulse-chase analysis in HEK-293T cells, we observed that S444A Nedd4-2 had a substantially shorter cellular half-life than WT Nedd4-2 (Fig. 4B). To examine further whether Nedd4-2 major site interaction with 14-3-3 proteins is important for Nedd4-2 cellular stability, we sought to disrupt 14-3-3 binding without eliminating phosphorylation at the major site. Thus, we co-expressed a generalized inhibitor of 14-3-3-target interactions, R18 WT peptide versus an inert control R18 M (mutant) (21). Although R18 WT but not R18 M inhibited the Nedd4-2–14-3-3 interaction by 75.6% ± 0.10% under these conditions (supplemental Fig. 2), there was no significant change in the decay for WT or S444A using these peptides. The decay of S444A with R18 WT versus mutant was 0.98 ± 0.18 h versus 1.17 ± 0.06 h, respectively (p > 0.4). WT Nedd4-2 did not substantially decay over this time interval, and thus its expression could not be fitted to an exponential decay curve. We further examined the stability of WT versus S444A Nedd4-2 using cycloheximide treatment to inhibit new protein synthesis and then following the decay of protein expression over time. Using the cycloheximide chase approach, we observed similar findings to metabolic pulse-chase assays (Fig. 5). WT Nedd4-2 with R18 WT versus mutant showed a similar stability compared with the more rapidly degraded S444A Nedd4-2. We observed that the decay of S444A Nedd4-2 with R18 WT versus mutant was 2.15 ± 0.33 h versus 1.87 ± 0.27 h, respectively (p > 0.5). These half-lives were delayed ∼1 h using this technique compared with metabolic pulse-chase analysis, likely representing a delay in the onset of protein synthesis inhibition with cycloheximide treatment. Additionally, we compared the decay of P446A Nedd4-2, a mutant form of Nedd4-2 that can be phosphorylated at the major site, but has decreased interaction with 14-3-3 (Fig. 2) (15). WT and P446A Nedd4-2 (independent of co-expression with R18 WT versus mutant) had similar stability (Fig. 5). Taken together, these data suggest that phosphorylation at the major site, but not 14-3-3 binding, plays an important role in cellular Nedd4-2 stability.

FIGURE 4.

Phosphorylation at the major site in Nedd4-2, but not 14-3-3 binding, is important for cellular stability as assessed by metabolic pulse-chase analysis. FLAG-Nedd4-2 and either wild-type (WT) or mutant (M) EYFP-R18 constructs were transfected into HEK-293T cells and radiolabeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 15 min before chase with nonradioactive buffer. Nedd4-2 was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG beads at indicated times after metabolic labeling. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and then assayed by exposure to a phospho-screen. A, representative blot of steady-state expression of WT and mutant Nedd4-2 24 h after transfection (n = 5). B, detection of [35S]Met/Cys-labeled Nedd4-2 by PhosphorImager after pulse-chase at indicated times. A representative image is shown. C, labeled protein abundance relative to time 0 fitted to an exponential decay curve using IGOR-Pro 4.0 software as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Decay curves for WT (circles) and major site mutant S444A Nedd4-2 (squares) with R18 WT (filled, dashed lines) or mutant (open, solid lines) are superimposed (n = 3).

FIGURE 5.

Phosphorylation at the major site in Nedd4-2 but not 14-3-3 binding is important for cellular stability by cycloheximide chase analysis. FLAG-Nedd4-2 and EYFP-R18 constructs were transfected into HEK-293T cells and treated with 100 μg/ml cycloheximide before chase with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer. A, detection of Nedd4-2 protein expression levels by immunoblotting after cycloheximide treatment for the various indicated times. A representative blot is shown. B, protein abundance relative to time 0 at the indicated times. Decay curves for WT (circles), P446A (triangles), and major site mutant S444A Nedd4-2 (squares) with R18 WT (filled, dashed lines) or mutant (open, solid lines) are superimposed (n = 3).

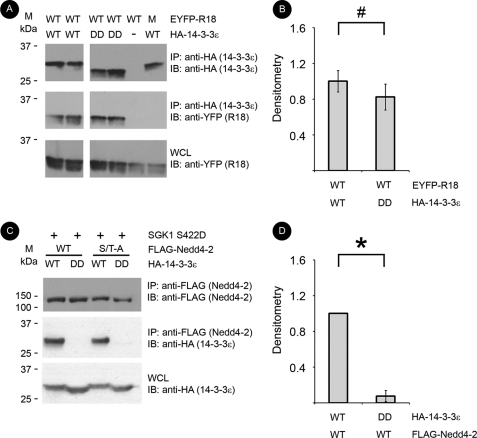

Dimerization of 14-3-3 Is Required for Interaction with Nedd4-2 at Major or Minor Sites

14-3-3 proteins typically bind to a target protein as dimers across two phosphorylated residues. However, a Nedd4-2 mutant lacking both minor sites (S338A/T363A) still interacted with 14-3-3 (Fig. 2). To characterize the role of Nedd4-2 major and minor sites further, we studied the importance of 14-3-3 dimerization on interaction with Nedd4-2. For these experiments we generated a dimerization-deficient mutant (DD) of 14-3-3ϵ. We focused on 14-3-3ϵ because this isoform has previously been shown to bind Nedd4-2 in an aldosterone-dependent manner (17, 25) and preferentially bound to Nedd4-2 compared with equivalent amounts of other 14-3-3 isoforms (supplemental Fig. 3). As predicted, DD 14-3-3ϵ was unable to bind other 14-3-3 isoforms but was capable of binding to b-Raf, a target of 14-3-3 that can bind a single 14-3-3 monomer (supplemental Fig. 4) (20). R18 peptides, which inhibit 14-3-3-target interactions, are high affinity monomeric targets of 14-3-3. Using EYFP-tagged R18 WT or an interaction-deficient mutant (M) (21), DD 14-3-3ϵ exhibited similar binding to R18 WT compared with WT 14-3-3ϵ in co-immunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, DD 14-3-3ϵ exhibited substantially reduced binding to Nedd4-2 (only 8.2% ± 7.3% that of WT 14-3-3ϵ) (Fig. 6, C and D). The double minor site mutant, S338A/T363A Nedd4-2, with only an intact major site, still requires dimerization-competent 14-3-3 for binding. Taken together, these results suggest that 14-3-3 dimers are required for significant interaction with Nedd4-2 at all sites, but these dimers may not always couple a major to a minor site according to the established paradigm.

FIGURE 6.

Dimerization is required for Nedd4-2–14-3-3 interaction, and dimers can bind to the major site independent of minor sites. EYFP-tagged R18 peptide (monomeric target of 14-3-3; either WT or mutant (M)), FLAG-Nedd4-2, HA-14-3-3ϵ, and/or SGK1 S422D constructs were co-expressed and immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-HA or anti-FLAG beads. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies. A, representative blots from the immunoprecipitated and whole cell lysates (WCL) are shown for immunoprecipitation of wild-type (WT) or DD HA-tagged 14-3-3ϵ with R18 peptides or WT Nedd4-2. B, densitometry of R18 band intensity normalized to immunoprecipitated 14-3-3 (#, p > 0.05; n = 4). C, representative blots from the immunoprecipitated and whole cell lysates for immunoprecipitation of WT or double minor site mutant (S/T-A) Nedd4-2 with WT or DD 14-3-3ϵ. D, densitometry of 14-3-3 band intensity normalized to immunoprecipitated WT Nedd4-2 (*, p < 0.01; n = 4).

DISCUSSION

We analyzed whether minor site phosphorylation of endogenous Nedd4-2 is the principal trigger for enhanced interaction with 14-3-3. By mass spectrometry we demonstrated that upon aldosterone treatment the largest increase in phosphorylation occurs at the minor site, Thr-363, and not at the major Ser-444 site. Flores et al. observed a modest increase in Nedd4-2 major site phosphorylation with short term aldosterone treatment (19). We employed a similar model system, mpkCCDc14 cells, and perhaps subtle changes in the cells or cell culture technique or choice of phosphatase inhibitors may have contributed to the magnitude of differences at the major site between this study and the earlier study. Additionally, we compared relative changes in phosphorylation at both major and minor sites. We found that, although aldosterone may modestly increase phosphorylation at the major site, the increase in minor site phosphorylation is substantially greater. We also found consistent results in two cell culture systems. Moreover, we have utilized both densitometric analysis and mass spectrometry to confirm differences at these phosphorylation sites. Two studies have examined the relative importance of each of the SGK1/PKA phosphorylation motifs within Nedd4-2 using site-directed mutagenesis. These studies showed that mutation of the major site, Ser-444 (or its equivalent), played a dominant role over mutation of one of the minor sites in disrupting SGK1- or PKA-inducible Na+ transport (1, 14). Furthermore, an antibody directed against the phosphorylated major site also decreased 14-3-3 binding and aldosterone-stimulated ENaC current (17). Our quantitative phosphorylation analysis prompts a refinement of the model by suggesting that although the major site is critical for 14-3-3 binding and ENaC regulation, it tends to be constitutively phosphorylated (Fig. 1). Thus, phosphorylation of a lower affinity minor site on Nedd4-2 (e.g. Thr-363) may serve as the physiologically relevant SGK1-dependent molecular switch. This paradigm differs from that involving other SGK1 targets such as the transcription factor Forkhead, FKHRL1, wherein SGK1 robustly phosphorylates both major and minor 14-3-3 binding sites to induce nuclear localization of FKHRL1 (26). Our findings imply that SGK1 integrates an aldosterone input signal with signals via other kinases (which phosphorylate the major site) to inhibit Nedd4-2 and to stimulate ENaC-mediated Na+ transport. Candidate kinases for the major site include Akt, PKA, and IκB kinase-β (27, 28).

We next investigated whether mutation of minor sites is sufficient to inhibit SGK1-mediated 14-3-3 interaction and Nedd4-2 inhibition. Alanine substitutions at minor sites, Ser-338 or Thr-363, decreased the interaction between Nedd4-2 and 14-3-3 (Fig. 2). Moreover, SGK1 could not rescue cell surface expression of α-ENaC when co-expressed with these minor site Nedd4-2 mutants (Fig. 3). Finally, expression of the T363A mutant decreased both 14-3-3 interaction with Nedd4-2 and SGK1 stimulation of ENaC surface expression to a greater extent than did expression of the S338A Nedd4-2 mutant. These results are consistent with our mass spectrometry data and with previous electrophysiologic data which demonstrated that the minor sites are important for regulating ENaC-mediated Na+ transport and that Thr-363 may be more important for the effects of SGK1 than Ser-338 (14). Interestingly, Ser-338 may preferentially determine regulation of Nedd4-2 and ENaC by vasopressin/PKA (14). Human Nedd4-2 is variably spliced at several exons, and one isoform (KIAA0439, GenBank accession no. AB007899) lacks only exon 12 and the residue equivalent to Thr-363 (29). Thus, it would be interesting to determine whether a higher proportion of this Nedd4-2 variant might protect against hypertension in different populations. Modulating regulation of this critical variant may also provide a selective drug target to disrupt aldosterone stimulation of ENaC activity.

Why is the major site phosphorylated under base-line conditions? Although the major site is necessary for interaction with 14-3-3 and inhibition of Nedd4-2, phosphorylation at this site alone is not sufficient to stimulate ENaC maximally because SGK1 cannot effectively augment ENaC activity when co-expressed with a minor site Nedd4-2 mutant. Furthermore, major site mutations result in markedly lower steady-state expression of Nedd4-2 protein in transfected cells. We tested the hypothesis that constitutive phosphorylation at the major site is necessary for Nedd4-2 stability. Using pulse-chase assays we demonstrated that the S444A phosphorylation-deficient mutant has a much shorter half-life than does WT (Fig. 4). R18 peptide, which decreases Nedd4-2–14-3-3 interaction without eliminating phosphorylation at the major site, did not decrease the half-life of Nedd4-2, which is consistent with a 14-3-3-independent effect on stability. Also consistent with this view, a P446A Nedd4-2 mutant, which selectively reduces 14-3-3 binding but not Ser-444 phosphorylation, also did not diminish the half-life of Nedd4-2. We cannot exclude that relative instability of the major site mutant could be due to nonspecific (or even specific) changes in protein folding. The prevention of major site phosphorylation with this mutant could induce changes in conformation, either locally or globally, that enhance its targeting for degradation in cells. Major site phosphorylation may thus be an important prerequisite to confer Nedd4-2 stability. The importance of phosphorylation at this residue is supported by our finding that the major site is highly phosphorylated in cells under base-line conditions (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the major site mutant Nedd4-2 robustly inhibits ENaC-mediated Na+ current, arguing that this mutation does not disrupt either the interaction with ENaC subunits or the ligase activity of Nedd4-2 (1, 14, 15). Thus, one or more kinases appear to preserve a high basal state of major site phosphorylation, which maintains Nedd4-2 expression independent of 14-3-3 interaction at the major site. Future experiments to delineate the physiologically relevant kinases that phosphorylate the major site should enhance our understanding of the regulation of Nedd4-2 stability. To the best of our knowledge, this suggests a novel mechanism by which the cellular stability and expression levels of E3 ubiquitin ligases may be regulated through phosphorylation. We speculate that this system provides an efficient method to fine tune the control of Na+ transport by permitting both ENaC inhibition in the absence of hormonal stimulation and ENaC stimulation in the presence of hormonal stimulation via the displacement of Nedd4-2 from ENaC by phosphorylation of a minor site, enhanced 14-3-3 binding, and Nedd4-2 sequestration from ENaC.

We have demonstrated that a double minor site mutant Nedd4-2, with only the major SGK1/PKA phosphorylation motif available, has ∼40–50% of the binding to 14-3-3 that occurs with WT Nedd4-2. These data suggest that 14-3-3 could bind in three possible states at the major site: as a monomer, as a dimer in a trans-configuration with the major site of another Nedd4-2 molecule or another 14-3-3-binding protein (e.g. AS160) (30), or finally as a dimer in a cis configuration by utilizing an unrecognized fourth 14-3-3 binding site on Nedd4-2. However, we have also shown that, in contrast to the monomeric 14-3-3 targets R18 WT or b-Raf, Nedd4-2 bound only weakly to DD 14-3-3. We speculate that 14-3-3 dimers bind Nedd4-2 at a major and minor site upon aldosterone treatment, but 14-3-3 proteins can bind at the major site and possibly a fourth binding site on Nedd4-2. This latter dimeric configuration would be in equilibrium with the classic dimer across one major, Ser-444, and one minor site, Ser-338 or Thr-363. We cannot rule out the possibility that 14-3-3 proteins could bind as a dimer across both minor sites upon aldosterone stimulation. However, neither phosphorylated motif has a Pro at the +2 position, and thus, they are not perfect consensus motifs for initial binding to 14-3-3 (31).

In conclusion, the complexity of phosphorylation and 14-3-3-mediated regulation of Nedd4-2 demonstrates additional controls on ENaC-mediated Na+ transport and ubiquitin ligase activity, in general. The results of this study refine the role of 14-3-3 proteins in the regulation of SGK1 stimulation of ENaC and expand the role of phosphorylation in the regulation of Nedd4-2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alan Pao and David Pearce for feedback.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants T32 DK007357-26 (to S. C.), R01 DK075048 (to K. R. H), and K08 DK071648 (to V. B.). This work was also supported by National Kidney Foundation Young Investigator Grant YIB787 (to V. B.) and by National Center for Research Resources Award S10RR027425 (to the Stanford University Mass Spectrometry Facility).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–4, Table 1, Experimental Procedures, and additional references.

- Nedd4-2

- neural precursor cell-expressed, developmentally down-regulated protein 4-2

- DD

- dimerization-deficient

- ENaC

- epithelial Na+ channel

- EYFP

- enhanced YFP

- mpkCCDc14

- mouse polarized kidney cortical collecting duct

- MS/MS

- tandem MS

- SGK1

- serum and glucocorticoid kinase 1

- xNedd4-2

- Xenopus Nedd4-2.

REFERENCES

- 1. Debonneville C., Flores S. Y., Kamynina E., Plant P. J., Tauxe C., Thomas M. A., Münster C., Chraïbi A., Pratt J. H., Horisberger J. D., Pearce D., Loffing J., Staub O. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 7052–7059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Staub O., Dho S., Henry P., Correa J., Ishikawa T., McGlade J., Rotin D. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 2371–2380 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Snyder P. M., Steines J. C., Olson D. R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5042–5046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bhalla V., Hallows K. R. (2008) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 1845–1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Michlig S., Harris M., Loffing J., Rossier B. C., Firsov D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38264–38270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schild L., Lu Y., Gautschi I., Schneeberger E., Lifton R. P., Rossier B. C. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 2381–2387 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shi P. P., Cao X. R., Sweezer E. M., Kinney T. S., Williams N. R., Husted R. F., Nair R., Weiss R. M., Williamson R. A., Sigmund C. D., Snyder P. M., Staub O., Stokes J. B., Yang B. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 295, F462–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abriel H., Horisberger J. D. (1999) J. Physiol. 516, 31–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kabra R., Knight K. K., Zhou R., Snyder P. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6033–6039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Malik B., Yue Q., Yue G., Chen X. J., Price S. R., Mitch W. E., Eaton D. C. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 289, F107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knight K. K., Olson D. R., Zhou R., Snyder P. M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 2805–2808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bhalla V., Oyster N. M., Fitch A. C., Wijngaarden M. A., Neumann D., Schlattner U., Pearce D., Hallows K. R. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26159–26169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hallows K. R., Bhalla V., Oyster N. M., Wijngaarden M. A., Lee J. K., Li H., Chandran S., Xia X., Huang Z., Chalkley R. J., Burlingame A. L., Pearce D. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 21671–21678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Snyder P. M., Olson D. R., Kabra R., Zhou R., Steines J. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45753–45758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bhalla V., Daidié D., Li H., Pao A. C., LaGrange L. P., Wang J., Vandewalle A., Stockand J. D., Staub O., Pearce D. (2005) Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 3073–3084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ichimura T., Yamamura H., Sasamoto K., Tominaga Y., Taoka M., Kakiuchi K., Shinkawa T., Takahashi N., Shimada S., Isobe T. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 13187–13194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liang X., Peters K. W., Butterworth M. B., Frizzell R. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 16323–16332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yaffe M. B. (2002) FEBS Lett. 513, 53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Flores S. Y., Loffing-Cueni D., Kamynina E., Daidié D., Gerbex C., Chabanel S., Dudler J., Loffing J., Staub O. (2005) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 2279–2287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tzivion G., Luo Z., Avruch J. (1998) Nature 394, 88–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Masters S. C., Fu H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 45193–45200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carattino M. D., Edinger R. S., Grieser H. J., Wise R., Neumann D., Schlattner U., Johnson J. P., Kleyman T. R., Hallows K. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17608–17616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shevchenko A., Tomas H., Havlis J., Olsen J. V., Mann M. (2006) Nat. Protoc. 1, 2856–2860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soundararajan R., Melters D., Shih I. C., Wang J., Pearce D. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 7804–7809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liang X., Butterworth M. B., Peters K. W., Walker W. H., Frizzell R. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27418–27425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brunet A., Park J., Tran H., Hu L. S., Hemmings B. A., Greenberg M. E. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 952–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee I. H., Dinudom A., Sanchez-Perez A., Kumar S., Cook D. I. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29866–29873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Edinger R. S., Lebowitz J., Li H., Alzamora R., Wang H., Johnson J. P., Hallows K. R. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 150–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Itani O. A., Stokes J. B., Thomas C. P. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 289, F334–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liang X., Butterworth M. B., Peters K. W., Frizzell R. A. (2010) Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 2024–2033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muslin A. J., Tanner J. W., Allen P. M., Shaw A. S. (1996) Cell 84, 889–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]