Abstract

AIM: To study the outcome of patients undergoing surgical resection of the bowel for sustained radiation-induced damage intractable to conservative management.

METHODS: During a 7-year period we operated on 17 cases (5 male, 12 female) admitted to our surgical department with intestinal radiation injury (IRI). They were originally treated for a pelvic malignancy by surgical resection followed by postoperative radiotherapy. During follow-up, they developed radiation enteritis requiring surgical treatment due to failure of conservative management.

RESULTS: IRI was located in the terminal ileum in 12 patients, in the rectum in 2 patients, in the descending colon in 2 patients, and in the cecum in one patient. All patients had resection of the affected region(s). There were no postoperative deaths, while 3 cases presented with postoperative complications (17.7%). All patients remained free of symptoms without evidence of recurrence of IRI for a median follow-up period of 42 mo (range, 6-96 mo).

CONCLUSION: We report a favorable outcome without IRI recurrence of 17 patients treated by resection of the diseased bowel segment.

Keywords: Pelvic neoplasms, Bowel, Radiation injuries, Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal radiation injury (IRI) is a common complication of radiation therapy for rectal, gynecologic and urologic malignancies. Despite improvements in radiation technology, the incidence of IRI is increasing mainly as a consequence of the rapidly expanding application of radiation plus chemotherapy in the management of pelvic malignancies[1,2]. It usually develops either early as acute radiation enteropathy, during or shortly after radiation therapy and resolving within 2-6 wk, or late, from 6 mo to as long as 30 years post radiotherapy as a chronic injury[3-9]. Although the true incidence of IRI has not been well defined, it varies from 1.2% to as high as 37% especially in patients with rectal cancer[5,6,8].

Surgical management of IRI patients adopts either a conservative approach with adhesionolysis, and/or creation of diverting stomas, or a more radical operation with resection of the diseased segment of the bowel. Morbidity, mortality and recurrence rate after these two surgical options in the management of radiation enteropathy have not been well documented.

We report on the clinical presentation, pathology and outcome of 17 consecutive IRI cases managed by surgical removal of the diseased segment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Of the 1261 patients irradiated for pelvic malignancies in the radiotherapy department of Metaxa Cancer Memorial Hospital during a 7-year period, 83 were hospitalized for IRI and 17 (5 male, 12 female) required surgery. Their mean age was 69.3 years (range, 46-88). They were irradiated with a mean dose of 48.6 Gy (range, 40-55Gy) for pelvic visceral organ malignancies. Their main presenting symptoms were: intractable abdominal pain in 10 patients, rectal bleeding in 5 patients, intractable diarrhea in 5, constipation in 3 and vomiting in 3. Eleven of the 17 patients had obstructive ileus and malabsorption before surgery. Table 1 provides comprehensive data of the operated patients.

Table 1.

Clinical presentation and surgical management of radiation enteritis patients

| Sex/age (yr) | Primary site of tumor | Radiation dose/period delivered (Gy/wk) | Dominant symptoms | Localization ofradiation lesions | Procedure | Morbidity/mortality | Follow-up(mo) |

| M/46 | Prostate | 70/7 | Blood PR, pain | Rectosigmoid | Hartman Procedure | -/- | 31 |

| M/74 | Prostate | 72/6 | Blood PR | Terminal Ileum | RC3 | SWI6/- | 25 |

| F/71 | Rectum | 52/4 | Pain, diarrhea | Terminal Ileum | RC | -/- | 42 |

| F/69 | Rectum | 50/4 | Pain, vomiting | Terminal Ileum | RC | -/- | 47 |

| F/69 | Rectum | 52/4 | Intestinal obstruction vomiting | Cecum | RC, ileostomy | -/- | 56 |

| F/83 | Rectum | 50/4 | Intestinal obstruction vomiting | Terminal Ileum | RC | -/- | 16 |

| F/66 | Urethra | 52/5 | Pain, diarrhea | Terminal Ileum | RC | Fecal fistula/- | 72 |

| M/74 | SML | 70/6 | Pain, diarrhea | Descending colon | LC | -/- | 8 |

| M/70 | Prostate | 70/7 | Intestinal obstruction vomiting | Terminal Ileum | RC | -/- | 72 |

| M/76 | Prostate | 70/6 | Blood PR | Rectosigmoid | LAR | -/- | 69 |

| F/88 | Cervix | 54/4 | Blood PR | Descending colon | LC | -/- | 84 |

| F/63 | Cervix | 54/4 | Pain | Terminal Ileum | RC | -/- | 79 |

| F/54 | Uterus | 50/8 | Pain, diarrhea | Terminal Ileum | RC | -/- | 96 |

| F/76 | Uterus | 50/5 | Pain | Terminal Ileum | RC | -/- | 12 |

| F/51 | Uterus | 48/4 | Pain | Terminal Ileum | RC | -/- | 27 |

| F/76 | Ovaries | 50/4 | Blood PR | Terminal Ileum | RC | SWI/- | 6 |

| F/73 | Uterus | 54/4 | Pain, diarrhea | Terminal Ileum | RC | -/- | 14 |

M: Male; F: Female; SML: Spinal metastasis from lung cancer; PR: Per rectum; RC: Right colectomy; LC: Left colectomy; LAR: Low anterior resection; SWI: Surgical wound infection.

Upon admission, all patients submitted to routine laboratory tests, endoscopic examination with biopsies, barium contrast studies of the small intestine and colon as required and computed tomography scans of the abdomen and pelvis. On admission they were placed on supportive measures to deal with the acute clinical situation and finally surgery was decided for failure of the conservative management approach.

RESULTS

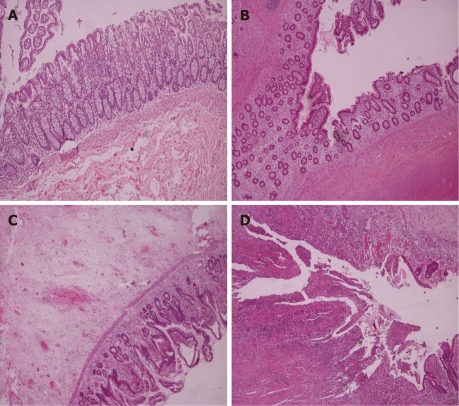

Of the 17 patents, 12 had right hemicolectomy, 3 had sigmoidectomy and 2 underwent low anterior resection. We treated all patients by resection of a variable length of bowel and primary anastomosis and only 2 required an isolated stoma after resection. Figure 1 shows characteristic histological manifestations of the broad range of IRIs observed in our patient group (Figure 1B-D) relative to normal tissue (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Representative histologic findings of normal (A) and radiation enteritis associated (B-D) intestinal mucosa. A: Normal; B: Mild lesions with edema and increased number of fibroblasts; C: Moderate lesions with sub-mucosal edema and disturbed mucosal architecture; D: Severe lesions with mucosal ulceration. Tissue sections were stained with standard hematoxylin-eosin (40 x magnification).

No postoperative death was recorded while morbidity was seen in 3/17 patients. Two patients developed abdominal wound infection and one an enterocutaneous fistula that was treated conservatively and required prolonged hospital stay (Table 1). No evidence of recurrent IRI disease was observed during a median follow-up period of 42 mo (range, 6-96 mo).

DISCUSSION

IRI symptoms appeared 6 mo to several years after radiation therapy. Their severity was disproportional to the extent of mucosal damage projected from the histology of the resected bowel (Figure 1). The shortened bowel and its mesentery along with marked compromise of the vasculature were common operative findings.

It is well recognized today that radiation-induced intestinal fibrosis seems to be the unifying underlying cause for most symptoms in patients who undergo postoperative radiotherapy for intra-abdominal malignancies. Abdominal pain, the most frequent symptom, is commonly due to intestinal obstruction or colonic loading and spasm, both treatable either by conservative measures or surgery[10].

The exact incidence of enteropathy lesions from radiotherapy varies considerably[11]. When a total radiation dose of 45 Gy is delivered, chronic radiation lesions will be observed in 5% of patients. With 65 Gy of radiation, as many as 50% of patients are likely to be affected. Late injuries develop ίin 2%-8% of patients within 12 to 30 mo after treatment[12-14]. A decreasing daily radiation dose increases the number of required sessions and minimizes radiation injury to normal tissue[15]. Certain medical conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiovascular disease, that affect blood supply and compromise the splanchnic circulation are associated with a higher incidence of bowel injury[16].

In our series no postoperative death occurred and the patient morbidity was 17.7% (Table 1). Reappraisal of the surgical treatment on 48 IRI patients reported 21.7% morbidity and 4.1% mortality following small bowel resection of the radiation-damaged bowel and restorative proctectomy for rectal disease[17]. Similar findings of 4.5% mortality and 30.2% morbidity after bowel resection on 109 operated patients with radiation enteritis and good life expectancy without recurrence of previous neoplastic disease have previously been reported[18].

The total dose of radiation therapy delivered to our patients never exceeded 55 Gy. In all patients adhesionolysis was performed before the definitive surgical procedure. All patients were followed for a median time of 42 mo and showed no evidence of IRI recurrence.

It is well known that acute infections secondary to mucositis of the oral cavity appear as complications after systemic chemotherapy and local radiation therapy for head and neck cancers[19]. Potential causes of increased incidence of infections are vascular damage impairing oxygen delivery and immunologic function, lymphatic vascular injury leading to lymphedema and soft tissue necrosis. Similarly, the radiation-induced bowel injury in patients who have also received chemotherapy renders them susceptible to septic complications. Thus, when surgery is mandatory and resection is feasible, it should be performed, since removal of the diseased bowel segment acting as a possible source of sepsis diminishes the risk of recurrence of IRI and improves patient outcome.

Use of preventive surgical measures to avoid the harmful consequences of IRI is the most preferable choice[20]. The 2 most common techniques utilized for IRI prevention have been the omental flap used as a sling across the pelvis[21] and an absorbable mesh to suspend the small intestine up out of the true pelvis. Another surgical technique involves peritoneal reconstruction using the posterior rectus sheath to form a tissue shelf just at the level of the umbilicus, suturing this to the sacral promontory[22,23]. Although the long-term efficacy of the above techniques is unproven, the poly-glycolic acid mesh sling appears to be the most reliable and reasonable method of keeping the small intestine out of the pelvis when postoperative pelvic radiation therapy is contemplated[24,25].

In conclusion, functional staging of IRI[26-28] may reveal either acute radiation enteritis or chronic radiation injury that should be managed conservatively. If that fails and resection of the diseased bowel is feasible[29], it should be adopted in all cases without exception.

COMMENTS

Background

Surgical resection of the radiation damaged bowel segment and primary anastomosis whenever possible is accompanied by a better outcome in patients who failed to respond to the original conservative management due probably to the removal of a septic area following surgical resection of the original pelvic malignancy and postoperative radiotherapy.

Research frontiers

The reasoning of this study is the development of an area in the radiation-damaged bowel that serves as a potential cause of sepsis not responding to conservative management and requiring radical measures for effective treatment.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Surgical removal of a sepsis inside the abdomen is always more effective resulting in a better outcome.

Applications

It is always desirable to be able to treat patients suffering from serious complications of radiation enteritis with radical resection if they fail conservative management.

Peer review

The article is an important topic. The problem of radiation-induced intestinal injury causes important morbidity. The number of patients in this series is small. However, the results are impressive.

Footnotes

Supported by The University Hospital of Larissa

Peer reviewers: Antonio Basoli, Professor, General Surgery “Paride Stefanini”, Università di Roma-Sapienza, Viale del Policlinico 155, Roma 00161, Italy; Dr. Benjamin Perakath, Professor, Department of Surgery Unit 5, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632004, Tamil Nadu, India; Michael Leitman, MD, FACS, Chief of General Surgery, Beth Israel Medical Center, 10 Union Square East, Suite 2M, New York, NY 10003, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Waddell BE, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Lee RJ, Weber TK, Petrelli NJ. Prevention of chronic radiation enteritis. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:611–624. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunnlaugsson A, Kjellén E, Nilsson P, Bendahl PO, Willner J, Johnsson A. Dose-volume relationships between enteritis and irradiated bowel volumes during 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin based chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:937–944. doi: 10.1080/02841860701317873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browning GG, Varma JS, Smith AN, Small WP, Duncan W. Late results of mucosal proctectomy and colo-anal sleeve anastomosis for chronic irradiation rectal injury. Br J Surg. 1987;74:31–34. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800740111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen-Mersh TG, Wilson EJ, Hope-Stone HF, Mann CV. The management of late radiation-induced rectal injury after treatment of carcinoma of the uterus. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987;164:521–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harling H, Balslev I. Surgical treatment of radiation injury to the rectosigmoid. Acta Chir Scand. 1986;152:691–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anseline PF, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Weakley FL. Radiation injury of the rectum: evaluation of surgical treatment. Ann Surg. 1981;194:716–724. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198112000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeoh E. Radiotherapy: long-term effects on gastrointestinal function. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2008;2:40–44. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3282f4451f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turina M, Mulhall AM, Mahid SS, Yashar C, Galandiuk S. Frequency and surgical management of chronic complications related to pelvic radiation. Arch Surg. 2008;143:46–52; discussion 52. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2007.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berthrong M, Fajardo LF. Radiation injury in surgical pathology: II Alimentary tract. Am J Pathol. 1981;5:581. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gami B, Harrington K, Blake P, Dearnaley D, Tait D, Davies J, Norman AR, Andreyev HJ. How patients manage gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:987–994. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wobbes T, Verschueren RC, Lubbers EJ, Jansen W, Paping RH. Surgical aspects of radiation enteritis of the small bowel. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:89–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02553982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.den Hartog Jager FC, van Haastert M, Batterman JJ, Tytgat GN. The endoscopic spectrum of late radiation damage of the rectosigmoid colon. Endoscopy. 1985;17:214–216. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quilty PM. A report of late rectosigmoid morbidity in patients with advanced cancer of the cervix, treated by a six week pelvic brick technique. Clin Radiol. 1988;39:297–300. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(88)80542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varma JS, Smith AN, Busuttil A. Correlation of clinical and manometric abnormalities of rectal function following chronic radiation injury. Br J Surg. 1985;72:875–878. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800721107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marks G, Mohiudden M. The surgical management of the radiation-injured intestine. Surg Clin North Am. 1983;63:81–96. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)42931-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeCosse JJ, Rhodes RS, Wentz WB, Reagan JW, Dworken HJ, Holden WD. The natural history and management of radiation induced injury of the gastrointestinal tract. Ann Surg. 1969;170:369–384. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196909010-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onodera H, Nagayama S, Mori A, Fujimoto A, Tachibana T, Yonenaga Y. Reappraisal of surgical treatment for radiation enteritis. World J Surg. 2005;29:459–463. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7699-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regimbeau JM, Panis Y, Gouzi JL, Fagniez PL. Operative and long term results after surgery for chronic radiation enteritis. Am J Surg. 2001;182:237–242. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00705-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maluf FC, William WN, Rigato O, Menon AD, Parise O, Docema MF. Necrotizing fasciitis as a late complication of multimodal treatment for locally advanced head and neck cancer: a case report. Head Neck. 2007;29:700–704. doi: 10.1002/hed.20558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmerer T, Böcker U, Wenz F, Singer MV. Medical prevention and treatment of acute and chronic radiation induced enteritis--is there any proven therapy? a short review. Z Gastroenterol. 2008;46:441–448. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1027150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russ JE, Smoron GL, Gagnon JD. Omental transposition flap in colorectal carcinoma: adjunctive use in prevention and treatment of radiation complications. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1984;10:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(84)90412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouraklis G. Reconstruction of the pelvic floor using the rectus abdominis muscles after radical pelvic surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:836–839. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theis VS, Sripadam R, Ramani V, Lal S. Chronic radiation enteritis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2010;22:70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devereux DF, Chandler JJ, Eisenstat T, Zinkin L. Efficacy of an absorbable mesh in keeping the small bowel out of the human pelvis following surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:17–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02552563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuech JJ, Chaudron V, Thoma V, Ollier JC, Tassetti V, Duval D, Rodier JF. Prevention of radiation enteritis by intrapelvic breast prosthesis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vamvakopoulos NV. Sexual dimorphism of stress response and immune/ inflammatory reaction: the corticotropin releasing hormone perspective. Mediators Inflamm. 1995;4:163–174. doi: 10.1155/S0962935195000275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nomikos IN, Vamvakopoulos NC. Correlating functional staging to effective treatment of acute surgical illness. Am J Surg. 2001;182:278–286. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00701-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sioutopoulou DO, Plakokefalos ET, Anifandis GM, Arvanitis LD, Venizelos I, Valeri RM, Destouni H, Vamvakopoulos NC. Comparing normal primary endocervical adenoepithelial cells to uninfected and influenza B virus infected human cervical adenocarcinoma HeLa cells. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:2032–2038. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gidwani AL, Gardiner K, Clarke J. Surgical experience with small bowel damage secondary to pelvic radiotherapy. Ir J Med Sci. 2009;178:13–17. doi: 10.1007/s11845-008-0181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]