Abstract

Using data from the Monitoring the Future study, this paper presents historical trends in U.S. high school seniors’ work values across 30 years (1976 to 2005. Adolescents across three decades highly valued most aspects of work examined. Recent cohorts showed declines in the importance of work, values for job security, and various potential intrinsic rewards of work. After increasing until 1990, adolescents remained stable in their values for extrinsic and materialistic aspects of work until 2005. The value of work that allows for leisure time has steadily increased. Stable level differences in work values emerged for adolescents by gender, race, parents’ education, and college aspirations. Findings have implications for understanding the changing meaning of work for the future workforce.

Keywords: adolescence, demographic differences, historical trends, Monitoring the Future, work values

The world of work has changed drastically since the 1970s. Over the past three decades, economists and members of the United States workforce have come to recognize job stability as a phenomenon of the past, as time-limited contracts and workers’ mobility across companies become the norm (Bluestone & Rose, 1997; Farber, 2006). In light of these economic changes, how have the meanings adolescents place on their future work life changed over historical time? Drawing from a social constructivist approach, we contend that individuals assign importance to various aspects of work based on their developmental and economic contexts as well as their own social locations. To better understand how work values have (or, have not) changed, we examine trends in high school seniors’ work values from the annual national Monitoring the Future survey (MTF) from 1976 to 2005. Specifically, we investigate trends in the importance of work, jobs that allow time for leisure, and values of job stability, as well as the extrinsic, materialistic, and intrinsic rewards of work. Differences based on gender, race, parents’ education, and adolescents’ educational aspirations are also examined.

Work Values in Developmental and Economic Context

Following Johnson and Elder (2002), we define work values as the importance one places on various characteristics and rewards of employment. Using a social constructivist perspective, our examination of work values is rooted in the idea that work is both an objective reality as well as a subjective social representation (e.g., collection of ideologies, values, opinions) for individuals and social or cultural groups (Gergen & Gergen, 2004; Liebel, 2004). U.S. high school seniors are on the cusp of adulthood and represent the nation’s future workforce; yet, because they have historically been left out of theory and research on work, we know very little about the meanings and values they assign to work (Liebel). Youth likely construct their own meanings of work that are unique in comparison to the conceptions of work espoused by adults. Furthermore, the social meanings of work collectively represent the interests of social groups, including both the dominant social classes and marginalized groups (Bourdieu, 1984; Evans, 2002; Lehmann, 2004; Liebel, 2004). High school seniors’ subjective views of work are important for gaining an understanding of how individuals at or near the beginning or their careers approach work and view it in the context of their personal lives. After first considering work values in the context of the developmental transition to adulthood, we outline the changing economic realities in which adolescents find themselves, and we then turn to the subjective meanings through which they anticipate their futures as part of the workforce.

Developmental context

Value development takes place primarily during adolescence (Flanagan, 2003a; Kelloway & Harvey, 1999), when youth also begin to think more deeply about work. Values are integral to identities and help adolescents define the self, make sense of experiences, and develop expectations for interactions with other people and institutions (Flanagan, 2003b). Values guide present and future behaviors (Rokeach, 1973), and are resources that underlie adolescents’ choices as they transition into adulthood (Eccles, Templeton, Barber, & Stone, 2003). Active exploration of potential careers, work values, and work competencies figures importantly into adolescents’ identity development (Erikson, 1968; Mortimer, Zimmer-Gembeck, Holmes, & Shanahan, 2002; Vondracek & Porfeli, 2003). The domain of work is not only central to adolescents’ identity exploration, but is also on the forefront of their minds in late adolescence when they start planning for the future (Eccles et al., 2003; Vondracek & Porfeli). Adolescents’ work values are in part derived from the perceived rewards of work and are associated with later work satisfaction (Johnson, 2001a, 2001b, 2002).

Of special relevance to the present paper, the values of young people are a barometer of social change. The ‘impressionable years model’ argues that adolescents’ and young adults’ values and attitudes are malleable and not yet crystallized. According to this perspective, young people are influenced by historical events, and these effects tend to be sustained over time as cohort effects (Alwin & McCammon, 2003; Mannheim, 1952; Ryder, 1965). In sum, young people construct their subjective meanings of work as they explore values and identities, and the development of work values has significance when viewed over historical time as work values portend social change for the future workforce.

In recent years the developmental period between adolescence and young adulthood has become protracted in the U.S. (Arnett, 2000; Settersten, Furstenburg, & Rumbaut, 2005). Identity exploration spans a longer period for many American youth, leaving values and attitudes in flux until their mid-to-late 20s (Arnett). The transition to adulthood once proceeded in an orderly sequence which included completing education, starting at the bottom of the career ladder, and working one’s way up. Today, however, the path to adulthood for adolescents is characterized by diverse life trajectories that lack a predictable sequence (Settersten et al., 2005). Recent trends suggest that young people remain in school longer, combine work and education, and delay marriage and having children (Fussell & Furstenberg, 2005). Indeed, the occupational aspirations of today’s adolescents are higher than any previous U.S. cohort, and adolescents are more likely than ever to aspire to graduate from a 4-year college (Schneider & Stevenson, 1999).

The transition to adulthood is not an experience of protracted exploration and continued education for all, however (Osgood, Foster, Flanagan, & Ruth, 2005), and the sequence of transitions into adult roles varies widely across individuals with different opportunities and from different cultural backgrounds (Mollenkopf, Kasinitz, & Waters, 2005). Individuals who enter the full-time workforce directly after high school often must take on more responsibilities and experience fewer freedoms compared to those in college (Eccles et al., 2003). Moreover, non-college bound youth are likely to experience several more years of job instability compared to those who attend college (Vondracek & Porfeli, 2003). Recent trends indicate that ethnic minorities (particularly African American and Latino youth), economically disadvantaged youth, and males are less likely to attend college (Lopez & Marcelo, 2006). Of course, disparities in education and opportunities for minorities and disadvantaged youth are apparent long before the transition to adulthood (cf. McLoyd, 1998). Accordingly, indicators of social location such as gender, race, parents’ education, and educational aspirations point to diverging pathways in how adolescents experience the work world, and may also illustrate differences in how adolescents make sense of work as part of their identities.

Economic context

Regardless of background, younger generations are coming of age in an economic context where work has been restructured to feature more episodic and insecure jobs with fewer benefits or guarantees (Bluestone & Rose, 1997; Farber, 2006; Flanagan, 2008). Job stability in the U.S. has been decreasing since the 1980s. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2006a, 2006b) reports that Americans typically hold an average of 10.5 jobs between ages 18 to 40, suggesting very little job stability across early adulthood. A large share of jobs in the U.S. labor force consist of work that is independently contracted, temporary, on-call, and part-time. National data from 1995, 2001, and 2005 revealed that 32%, 29%, and 31% of the workforce during those years, respectively, were employed in such “non-standard” jobs (Mishel, Bernstein, & Allegretto, 2007). The service industry represents a growing sector of the workforce, where prerequisite job skills are minimal and employees are easily interchangeable. Non-standard and service industry jobs tend to be characterized by lower pay, lower benefits, and less job security than full-time positions or positions in other sectors (Mishel et al.). The increasing educational and occupational ambitions of high school seniors may, in part, be a response to these labor market shifts, as jobs not requiring higher education are less and less likely to offer economic security (Reynolds, Stewart, MacDonald, & Sischo, 2006; Schneider & Stevenson, 1999).

Not surprisingly, individuals without college degrees and minorities are disproportionally burdened by the increasing vagaries of the market. Increases in job transitions may be a deliberate choice by college graduates to explore career options, whereas for young people without college degrees, job transitions may be necessary for maintaining employment and may indicate economic vulnerability (Farber, 2006). Moreover, declines in job stability are felt disproportionately by African Americans (especially African American men, Bluestone & Rose, 1997), less educated workers, and younger workers (Danziger & Gottschalk, 2004; Hill & Yeung, 1999; Marcotte, 1999). Compounding this issue is the already noted fact that young people of ethnic minority backgrounds, particularly African Americans and Latinos, are less likely to attend and graduate from college (Lopez & Marcelo, 2006).

Job loss and job transitions can be costly and anxiety-provoking for workers, even in good economic times - a fact documented by economists and government officials alike (Farber, 2005; Greenspan, 2004). Some have noted that the uncertainties of the economy produce uncertainty and anxiety in young people, as well (e.g., Flanagan, 2005, 2008). The realities of work have certainly changed for the adult workforce given the increases in job instabilities, and economists place a high priority on understanding these market shifts. Less well understood are the changes over historical time in the work values of adolescents (i.e., the future labor force). Their views are constructed in part based on their developmental, social, and economic contexts, and they will most likely carry these views into adulthood.

Past Trends in Adolescents’ Work Values

In an effort to understand and document historical shifts in adolescents’ values related to future employment, several studies have used MTF data to examine work values in high school seniors across shorter periods of time (Crimmins, Easterlin, & Saito, 1991; Easterlin & Crimmins, 1991; Schulenberg, Bachman, Johnston, & O’Malley, 1994). For the period from 1976 to 1992, these studies found a decrease in high school seniors’ values for work as a central part of life and an increase in values of materialism and extrinsic work characteristics, such as work that provides status and money as opposed to opportunities to help others. Furthermore, Schulenberg and colleagues documented an increase over this period in the value for work that provides more than two weeks of vacation.

Examining MTF panel data across the transition to adulthood, Johnson (2001a, 2001b, 2002) found an overall pattern of decline in a range of work values from ages 18 to 32. This general pattern of decline fits the thesis that adolescents’ work values may be unrealistically high in relation to the jobs likely to be available to them in the labor market as adults (Johnson, 2002; Marini, Fan, Finley, & Beutel, 1996). Despite some decline with age, work values also became increasingly stable over time (Johnson, 2001b). Moreover, intrinsic values were the most highly rated work values and declined the least across young adulthood (Johnson, 2001b, 2002).

Demographic differences

Schulenberg et al. (1994) found that adolescent girls reported higher intrinsic work values (e.g., importance of creativity, decision making, and helping others at work) whereas boys reported higher extrinsic work values. Other aspects of individuals’ social location also play a role in initial levels of adolescents’ work values: Compared to Black females, White males and females reported lower extrinsic and job security values, and parents’ educational attainment, a proxy for socioeconomic status, was also negatively associated with adolescents’ extrinsic and job security values (Johnson, 2002; Johnson & Elder, 2002).

Using MTF longitudinal panel data, Johnson and Elder (2002) examined the associations between work values and educational attainment across young adulthood (ages 18 to 32). They found that youth with no college education started with higher extrinsic values that declined substantially with age, whereas those with associate’s or bachelor’s degrees started with lower extrinsic values that declined less with age. In addition, adolescents most concerned with job security as high school seniors were least likely to continue their education in young adulthood. Furthermore, youth with only a high school diploma maintained high levels of concern with job security in young adulthood, compared to individuals obtaining a college degree (associate’s, bachelor’s, or beyond), whose values for job security declined. Few other studies have examined differences in work values trends for groups with differing educational aspirations. The present study will distinguish between adolescents who aspire to graduate from a 4-year college, a 2-year college only, or who have no college plans. Comparing the work values of these groups of adolescents should illuminate variations in constructed meanings, perceived opportunities, or concerns about adapting to realities of the work world.

Present Study

We extend previous research by documenting changes in adolescents’ work values across a period of 30 years (1976–2005). There are two key reasons to examine adolescents’ work values from 1976 to 2005: (1) Several key shifts in the economic context from the early 1990s to 2005 call for an updated examination of the meaning adolescents place on work, and (2) more research is needed that examines various indicators of adolescents’ social location in tandem with the evolving meanings and values that adolescents have placed on work in recent decades.

Thus, this study has two aims. First, we explore a range of dimensions that high school seniors use to construct their social representations of work, including work centrality, job stability, extrinsic work values, materialism, and intrinsic work values. Examination of these trends extends previous research on these topics (Crimmins et al., 1991; Easterlin & Crimmins, 1991; Schulenberg et al., 1994) by paying particular attention to change across the last 13 years of survey data. Second, for each trend, we estimate differences in work values by gender, race, parents’ education, and adolescents’ college aspirations.

Method

Data come from the 12th grade Monitoring the Future survey, a project studying American high school students’ attitudes, values, and lifestyles with a focus on substance use (Johnston, Bachman, & O’Malley, 2006). In this ongoing study, a nationally representative sample of high school seniors has been surveyed each year since 1976, selected by a multi-stage sampling procedure from public and private high schools across the United States. Our study uses publicly available data on senior class cohorts from 1976 to 2005, the extent of data available at time of analysis. The study design enables us to shed light on social change by describing time trends in the meanings high school seniors place on work. Age is held relatively constant as high school senior cohorts vary little in age, and thus changes cannot be attributed to age differences. With sample weights, annual samples are nationally representative so it is unlikely that differences over time are attributable to certain types of adolescents being overrepresented in certain years. Analyses control for changes in the ethnic composition of the population over time. Therefore, shifts in work values across time are more likely attributable to changes in economic, social, or historical milieus in which adolescents experienced childhood and/or experiences of historical events during adolescence (i.e., cohort or period effects).

MTF surveys use six questionnaire forms, with random subsamples of around 3,000 adolescents answering each form yearly. Our data primarily come from Form 4, with a few items taken from Forms 1, 3, and 5. As noted, analyses use the sample weights provided with the data, which are designed to make the results representative of the national population of high school seniors (Bachman, Johnston, O’Malley, & Schulenberg, 2006). Weighted sample sizes for each analysis ranged from 90,121 to 92,622 (median N = 91,808).

Measures

The majority of items concerning work values on which we focus come from a set of questions starting with the following introduction: “Different people may look for different things in their work. Below is a list of some of these things. Please read each one, then indicate how important this thing is for you.” For ease of interpretation and to allow for direct comparisons across measures, we dichotomized responses to all items. Unless otherwise noted, responses were recoded from a 4-point scale: not important or a little important (0) and pretty important or very important (1). Each item was analyzed as a separate outcome measure, though some items are combined to facilitate the graphical presentation of results.1

Importance of work

Several items measured the priority placed on work. One item measured adolescents’ expectations for the centrality of work via agreement to the statement, “I expect work to be a central part of my life.” A second item tapped adolescents’ willingness to work overtime: “I want to do my best in my job, even if this sometimes means working overtime.” These two items were recoded so that 0 = disagree, mostly disagree, or neither disagree or agree and 1 = agree or mostly agree. A third dichotomous item asked adolescents if they would work even if they had enough money to live comfortably; response choices were I would not want to work (0) versus I would want to work (1).

Work that allows time for leisure

Two items measured the value of work that allows time for leisure: the importance of a job “where you can have more than two weeks vacation” and “which leaves a lot of time for other things in life.”

Job stability

A single item gauged the value for job security through adolescents’ ratings of the importance of having a job “that offers a reasonably predictable and secure future.” A second item asked adolescents whether they would like to keep the same job most of their adult lives. The latter item was coded so that the lower score reflected lower value of stability (i.e., 0 = disagree, mostly disagree, or neither disagree or agree) and the higher score reflected higher value of job stability (i.e., 1 = agree or mostly agree).

Extrinsic rewards

Extrinsic work values, measured by four items, included the importance of having a job “that has high status and prestige,” “that most people look up to and respect,” “where the chances of advancement and promotion are good,” and “which provides you with a chance to earn a good deal of money.”

Materialism

Three items measuring the value of materialism included: the importance of having lots of money, expecting to own more than one’s parents, and only being happy with owning more than one’s parents. Responses for the latter two items were recoded so that participants who expected to have much less than my parents, somewhat less than my parents, or about as much as my parents were coded as 0 and those who expected to have somewhat more than my parents or much more than my parents were coded as 1.

Intrinsic rewards

Trends in intrinsic work values were assessed using five items, including the importance of having a job that “is interesting to do,” “uses your skills and abilities - lets you do things you can do best,” and a job where “you can see the results of what you do,” “you can learn new things, new skills,” and “the skills you learn will not go out of date.”

Demographic variables

Our analyses take into account four aspects of respondents’ social locations: gender (coded 0 = male, 1 = female), race/ethnicity, parents’ education, and college aspirations. The publicly available MTF data distinguish only the three race/ethnicity categories of white, black, and all other, which we capture with dummy variables, using white as the reference category. Parents’ education provides the sole indicator of respondents’ family socioeconomic status, and we capture this with the dichotomy of high school diploma or less versus at least some post-secondary education. The sample was split into three groups based on college aspirations. Two items asked about adolescents’ intentions to graduate from 2- and 4-year college, respectively. We created mutually exclusive groups consisting of adolescents who do not expect to graduate from college (either 2-year or 4-year), who state that they will probably or definitely graduate from 2-year college (but not a 4-year college), and who state that they will probably or definitely graduate from 4-year college. We classified adolescents who reported intent to graduate from both a 2-year and 4-year college according to the higher degree expected for simplicity and ease of interpretability.

Results

Generalized Linear Models

Each item was examined in a separate analysis using the generalized linear model with a logit link function to model a dichotomous distribution. Each regression model included the explanatory variables of year (entered as a series of 29 dummy variables), gender (male vs. female), race (White, Black, and other), parents’ education (high school diploma or less vs. post-high school education), and college plans (no plans, 2-year plans, and 4-year plans). Statistical significance for the set of years was examined by calculating the likelihood ratio chi square test comparing a full model to a model excluding dummy variables for year. Parameters for each year could not be shown due to space limitations, yet, as Table 1 indicates, all time trends are most definitely statistically significant (all likelihood ratio χ2 values exceed 165, df = 29, p’s < .001).

Table 1. Demographic Correlates and Time Trend Significance Tests by Item from Generalized Linear Models.

| Work Values | Femalea | Blackb | Other Racesb |

High Parent Educationc |

2-Year College Plansd |

4-Year College Plansd |

Time Trend Likelihood Ratio χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance of Work | |||||||

| Work Centrality | −.05*** | .63*** | .09*** | −.08*** | .07** | .13*** | 1208.22*** |

| Work Even if Unnecessary | .38*** | .11*** | .26*** | .04* | .14*** | .24*** | 650.21*** |

| Overtime | .32*** | .18*** | −.10*** | −.06* | .13*** | .25*** | 675.55*** |

| Job Allows Time for Leisure | |||||||

| Vacation Time | −.53*** | .20*** | .23*** | .06*** | .05** | −.01 | 1020.77*** |

| Life Outside of Work | −.39*** | .09** | .04 | .004 | .06* | .02 | 225.98*** |

| Job Stability | |||||||

| Security | .21*** | .23*** | −.10** | −.21*** | .30*** | .19*** | 207.02*** |

| Keep the Same Job | −.04** | −.23*** | −.33*** | −.09*** | .05† | .06** | 379.01*** |

| Extrinsic Rewards | |||||||

| Status and Prestige | −.21*** | .90*** | .47*** | −.21*** | .13*** | .13*** | 696.31*** |

| Respect | .21*** | .49*** | .21*** | −.09*** | .20*** | .25*** | 246.20*** |

| Advancement | −.22*** | .64*** | .01 | −.21*** | .27*** | .21*** | 253.86*** |

| Earn Money | −.39*** | 1.00*** | .33*** | −.36*** | −.48*** | −.38*** | 270.63*** |

| Materialism | |||||||

| Earn Lots of Money | .57*** | .82*** | .42*** | −.05*** | .08*** | −.002 | 1319.22*** |

| Expect More than Parents | −.30*** | .89*** | .36*** | −.35*** | .36*** | .61*** | 728.39*** |

| Happy w/ More than Parents | −.27*** | 1.19*** | .72*** | −.44*** | .14*** | .13*** | 501.15*** |

| Intrinsic Rewards | |||||||

| Interesting Job | .80*** | −.97*** | −.74*** | .26*** | .35*** | .85*** | 165.53*** |

| Use Skills | .57*** | −.10* | −.16*** | .12*** | .26*** | .49*** | 181.77*** |

| See Results | .39*** | .26*** | .06† | −.02 | .17*** | .37*** | 437.49*** |

| Learn New Skills | .37*** | .90*** | .53*** | −.20*** | .06† | −.16*** | 370.92*** |

| Adaptable Work Skills | .06*** | .27*** | .08** | −.14*** | −.04 | −.15*** | 241.78*** |

Notes. Reference groups are:

Males

Whites

Participants whose parents had a high school diploma or less

participants with no college plans.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

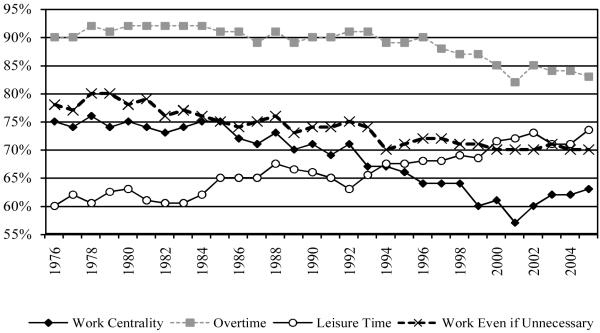

Importance of Work

Since the mid 1980s, adolescents have become much less likely to view work as a central part of their lives (see Figure 1). Though the majority of high school seniors have considered work central throughout this period, endorsement of work centrality steadily declined from its peak in 1978 (76%) to its lowest point in 2001 (57%), before upturning slightly from 2002 to 2005. This result extends previous findings of a declining trend in work centrality documented up to 1992 (Crimmins et al., 1991; Schulenberg et al., 1994), and shows that the decline continued throughout the 1990s before rebounding somewhat in the early 2000s.

Figure 1. Trends in Work Centrality, Work Even if Unnecessary, Overtime, and Leisure Time.

We also found steadily declining trends in high school seniors’ willingness to work regardless of their need for money and to put in overtime in order to do their best. Specifically, 78% of high school seniors in 1976 said that they would work even if they had enough money to live comfortably without working compared to 70% in 2005. Put another way, adolescents have increasingly reported that if they already had enough money, they would not work. The decline in high school seniors’ willingness to work overtime was particularly sharp over the period between 1993 and 2005 (see Figure 1). Overall, high school seniors on average reported high values for work as central to their lives, yet all three trends declined over time.

As shown in Table 1, gender differences varied across items; males reported slightly higher values of work centrality, whereas females reported considerably greater willingness to work overtime and to work even if unnecessary for money. Black adolescents and adolescents with 2-year or 4-year college aspirations reported greater importance of work across the three items than did white adolescents and adolescents who did not expect to earn any college degree. Differences between other race/ethnicity groups and whites and by parents’ education were smaller and not consistent across the importance of work items.

Value of Work that Allows Time for Leisure

Trends in valuing work that allows time for leisure contrasted with the declining trends in work centrality (see Figure 1). More specifically, trends showed a gradual increase over time in the value for jobs that offer more than two weeks of vacation as well as jobs that leave time for other things in life (combined in Figure 1). Males, Blacks, and (to a small degree) adolescents with 2-year college plans reported higher values of work that allows time for leisure.

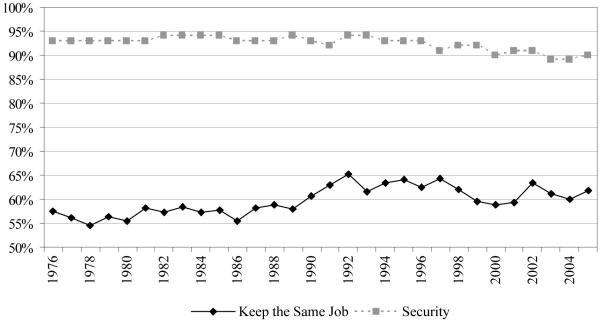

Job Stability: Security and Keeping the Same Job

In recent years adolescents have come to hold somewhat less value for a predictable and secure job (see Figure 2). Extending Schulenberg et al.’s (1994) earlier report, we found that job security has become slightly less important for adolescents through the 1990s and early 2000s than it was for adolescents in the 1980s and late 1970s. The recent relative decline is noteworthy given the high desirability of this job characteristic, which was endorsed by an average of 92% of high school seniors across all 30 years. Females, Blacks, those with lower parent education, and those with 2-year or 4-year college aspirations reported greater values for job security.

Figure 2. Trends in Youth Values and Expectations of Job Stability.

The trend is more complex for high school seniors’ desire to hold the same job for most of their adult lives, which was relatively stable from 1976 to 1988, gradually increased from 1989 to 1992, remained higher across the mid-1990s, and then declined and leveled off in the first part of 2000s (see Figure 2). Across the 30-year period, 57% to 65% of adolescents endorsed wanting to keep the same job for most of their lives. Adolescent males, Whites, those with lower parent education, and those with 4-year college plans had higher endorsements of keeping the same job for most of their lives.

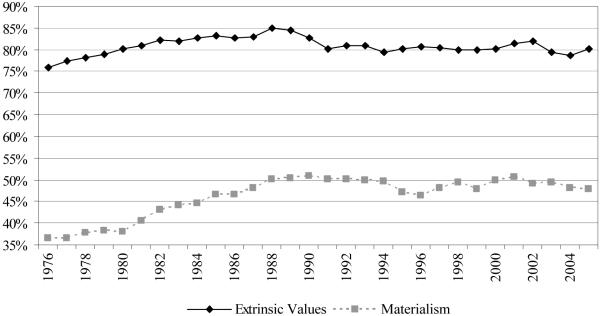

Extrinsic Work Values and Materialism

The value high school seniors placed on status and prestige, respect, advancement, and earnings (graphed together as “extrinsic work values” in Figure 3) increased from the late 1970s until the late 1980s, when they reached their highest levels (84–85%). After a moderate decline from 1990 to 1992, these values have remained high and stable at around 80% through the 1990s and early 2000s. High school seniors’ values of materialism followed a similar pattern but with an even bigger increase until the late 1980s before stabilizing (see Figure 3). Compared to 1976, recent cohorts placed somewhat higher value on extrinsic rewards of work (by 4% to 7%) and held considerably more materialistic values (by 11% to 14%).

Figure 3. Trends in Youth Values of Extrinsic Work Characteristics and Materialism.

Similar patterns in demographic differences emerged across extrinsic values and materialism. Males reported higher extrinsic values of all types, except that females reported higher values for a job that provides respect. Ethnic minorities and those with lower parent education reported higher extrinsic work values. Adolescents with 2-year and 4-year college plans reported higher extrinsic values of all types, except that adolescents with no college plans more highly valued earning money.

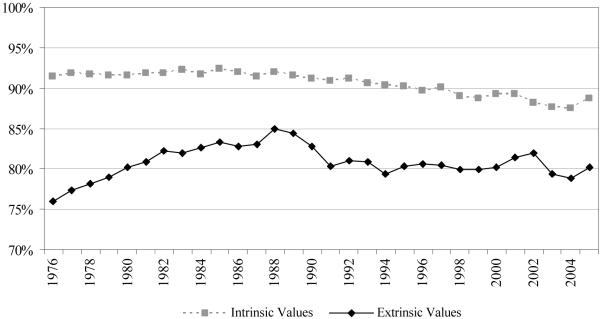

Intrinsic Work Values

High school seniors’ intrinsic work values, which included the importance of acquiring and maintaining a useful set of skills, seeing the results of one’s work, and having a job that is interesting, declined slightly between 1976 and 2005 (see trend for the five combined intrinsic work values items in Figure 4). Intrinsic work values remained stable at their peak of 92% across most of the late-1970s and 1980s and then declined across the 1990s and early 2000s to a low of 88% in 2004. The pattern of decline from 1990 onward was modest yet significant. Moreover, though intrinsic values are - in general - much higher than extrinsic values, intrinsic and extrinsic work values have somewhat different patterns. As illustrated in Figure 4, adolescents’ intrinsic work values remained stable during the 1970s and 1980s and then declined for the remainder of the period, whereas extrinsic work values increased through the 1970s and 1980s and remained stable after some reversal in the early 1990s.

Figure 4. Trends in Intrinsic and Extrinsic Work Values.

Females reported higher intrinsic work values for all five items. Other demographic patterns varied by item. White adolescents as well as those with 4-year plans and higher parental education more highly valued work that is interesting and uses skills and abilities, and reported lower values for work that teaches new skills and uses adaptable work skills. Adolescents with 2-year college plans more highly valued work that is interesting, uses skills, and produces visible results than those with no college plans. Black adolescents and those with 2-year college plans were more likely to value work that produces visible results than their counterparts.

All items evidenced level differences by demographic characteristics; only trends in the value for new and adaptable work skills showed differential change over time for respondents with different college aspirations. Although all adolescents placed declining value on these two intrinsic values, the decline was smallest among respondents with 2-year college plans, who remained most attuned to the need for a transferable skill set. The divergence in trends began in about 1992. Generalized linear logit models for these two items showed few significant differences between youth with 2-year plans and the other two groups before 1992, yet after, adolescents with 2-year plans held significantly higher values for new and adaptive work skills than those with 4-year plans or no college plans.2

Discussion

Our findings document the various meanings that recent and past cohorts of high school seniors associate with work; these values vary consistently by adolescents’ social locations and can be informative for adolescents’ identity development and expectations as they enter the changing world of work. Viewing work-related social and economic milieus through the eyes of adolescents in this way sheds light on the opportunities and futures different groups of adolescents perceive as being available to them. In concluding, we discuss historical shifts and subgroup differences in work values and highlight limitations and implications of these findings.

Historical Shifts in Work Values

Elaborating and extending previous research, our study documents 30-year trends in high school seniors’ work values, measured multidimensionally via the importance of work, job stability, extrinsic and materialistic rewards, and intrinsic characteristics. Trends in adolescents’ work values are important additions to our knowledge for two reasons: First, sociological theorists argue that historical events influence adolescents more than adults (Alwin & McCammon, 2003; Mannheim, 1952; Ryder, 1965), and thus shifts in adolescents’ work values may signal key widespread social and/or economic changes. Second, adolescents represent society’s future workforce, and the meanings they bestow on work provide some basis for understanding what they expect to find as they transition into the work world. Our findings support the observations of others (Johnson, 2002; Marini et al., 1996) that adolescents generally reported high values for many, if not all, aspects of work. We also found meaningful shifts across three decades in adolescents’ work values. We discuss these in turn.

Importance of work

Trends in the importance that high school seniors place on work as central to one’s life, work even if unnecessary for money, and willingness to work overtime to do one’s best, particularly since the 1990s, show that adolescents have been placing lower priority on work as important for its own sake compared to their peers in the 1970s and 1980s. These declining trends are perhaps best understood in the context of other trends we examined. Viewed alongside declining trends for intrinsic work values, stable extrinsic work values, and increasing values of work that allows time for leisure, it appears that more recent cohorts of high school seniors have lower expectations that employment will be a source of meaning or purpose in their adult lives. Various explanations for these trends are plausible. For example, this pattern of a decreased investment in work could signal a recognition that fewer available jobs means fewer choices or a healthy realization that work should not consume life completely. This pattern of decreased investment in work could also portend negative implications for the productivity and well-being of the future workforce, particularly given that recent cohorts are less inclined to value work that is interesting and uses their skills and abilities.

Job stability

Approximately 60–65% of high school seniors since 1990 have desired to hold the same job for most of their adult lives, yet adolescents have placed declining value on job security (i.e., a job with a predictable and secure future) in recent years. In the context of labor market changes in which available jobs increasingly offer non-standard shifts and temporary or part-time work with lower pay and fewer benefits (Bluesone & Rose, 1997; Mishel et al., 2007), this decline may reflect a realistic expectation. Labor statistics (e.g., Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2006a, 2006b) show that job stability is unlikely for most young adults. This trend could reflect a positive adaptation to labor market trends or a resignation to the reality of diminishing opportunities for job security. Regarding the latter possibility, economic uncertainties tend to engender anxieties about one’s future in the work world (Flanagan, 2008). During the 1990s and early 2000s, adolescents may have shifted their expectations after observing parents’ multiple job transitions or media accounts of changing industry characteristics.

Extrinsic and intrinsic values

Since the early 1990s, high school seniors have placed decreasing value on intrinsic rewards of work while maintaining or increasing desires for extrinsic and materialistic rewards. Intrinsic work values have consistently received higher endorsement than extrinsic work values across the 30-year period, and their patterns of change were different. The rise in extrinsic values in the 1970s and 1980s and stability thereafter may reflect those cohorts’ increasing materialism and drive for attainment of status and wealth (Putnam, 2000). Further, competition is heightened in climates of greater economic uncertainty, and an atmosphere of competition breeds achievement orientations and extrinsic pursuits (Inglehart, 1997). In times of economic change, money and related extrinsic work values may be the only sure things the work world provides (Inglehart); this idea is consistent with the pattern of stable extrinsic values and declining work centrality and intrinsic work values.

The decline in intrinsic values is also noteworthy given that three of the items deal with updating and using one’s skill set. The need for all workers to continually increase their skills is inevitable due to technological innovations across industries (Bills, 2005; Fernandez, 2001). In this light, the declining trends in adolescents’ values related to new, useful, and adaptive work skills seem particularly mismatched with market trends.

Interestingly, since the 1990s, high school seniors with 2-year college aspirations compared to their peers have more highly valued learning new work skills and having a job where skills do not go out of date. This trend looks particularly adaptive for this group in terms of the current labor market context. Indeed, community colleges provide a money-saving option for getting a 4-year degree through transferring as well as more practical work skills and higher earning potential compared to a high school diploma (Gracie, 1998; Phillipe, 2005; Settersten, 2005). It is also plausible that adolescents who highly valued work skills have shifted educational aspirations towards a 2-year degree as a way to best meet their expectations.

Demographic Differences

Our findings clearly indicate that adolescents’ work values vary by social location. Analyses significantly extend previous work (Schulenberg et al., 1994) by examining multiple characteristics simultaneously and across a longer time interval. As a social constructivist approach argues, adolescents’ views of work collectively represent the perspectives that are characteristic of their positions in the social structure (Liebel, 2004).

Gender

Males expressed greater support for extrinsic work values, whereas females reported more support than males for intrinsic work values. Findings are consistent with prior work (Schulenberg et al., 1994), and they fit with the broader values literature wherein females consistently show a stronger orientation towards intrinsic pursuits and care orientations and males are more extrinsically-oriented (Beutel & Marini, 1995). Males continue to more highly value work centrality compared to females (see also Schulenberg et al., 1994). We also found that females placed more value on a job that people respect (an extrinsic work value), which may reflect a desire to move past the traditional association of women with lower status jobs.

Race and parents’ education

Adolescents of ethnic minority backgrounds (Black and other non-white ethnicities) and those whose parents had a high school diploma or less showed a similar response pattern: Adolescents of ethnic minority backgrounds and low socioeconomic status generally reported higher expectations for work on a variety of dimensions, including work centrality, job security, extrinsic values, and several intrinsic values, compared to their white and higher SES counterparts. This pattern is intriguing and suggests that the meanings minority group members place on work should be studied in more depth, particularly as the vagaries of the job market, such as declines in job stability, are disproportionately felt by minorities and the economically disadvantaged (Bluestone & Rose, 1997; Danzinger & Gottschalk, 2004; Hill & Yeung, 1999).

College aspirations

Our findings concerning the relationship between work values and adolescents’ college aspirations are a novel contribution to the literature, as they usefully combine information about these values with adolescents’ plans for next steps toward job or career preparation. Compared to peers with no college plans, high school seniors with 2-year and 4-year college aspirations more highly valued work centrality, job security, extrinsic work characteristics (except for earning money), materialism, and the intrinsic rewards of work that is interesting, uses one’s skills and abilities, and produces visible results. These adolescents were optimistic about the possibilities of their future careers and expectations for intrinsic rewards of work. More youth each year are attending college, and the protracted transition to adulthood may mean that these adolescents, particularly those who transition to a 4-year institution, can take longer to solidify their career goals and aspirations (Settersten et al., 2005). Adolescents with 2-year college plans stood out in valuing work that allows time for leisure more so than youth with no college plans, and, as discussed above, in their unique pattern of change for values of learning new and adaptable work skills. Adolescents planning to graduate from 2-year colleges are an important population in need of further study, particularly as this path of higher education is growing, affordable, and offers practical training as well as opportunities to transfer to 4-year institutions (Phillippe, 2005; Settersten, 2005).

Of course, not all high school seniors pursue a college education, and not all youth who enroll in college actually graduate (Mortimer et al., 2002). Our results show that high school seniors with no college aspirations look quite different from their peers with college plans in terms of work values. They were also most likely to value earning money, which may be unrealistic insofar as they are likely to start or continue low-skill, entry-level jobs after high school. As they transition to adulthood, youth with only a high school diploma report even lower extrinsic work values, yet maintain high values of job security (Johnson & Elder, 2002). Future work should consider the different avenues by which work expectations are shaped for different groups of youth; for all youth, sorting processes are likely to begin long before their senior year of high school (e.g., Johnson, 2002; McLoyd, 1998).

Limitations

This study is limited by several factors. First, although we interpreted responses as referring to future rather than current employment, the items themselves are not explicit in this regard and some respondents could have interpreted items to refer to current jobs. We believe, however, that respondents rarely thought in terms of current employment, given the high importance respondents placed on job features rare in adolescent employment, such as paid vacation and long-term job security. Second, our study discussed broad economic trends as a context for considering trends in adolescents’ work values, yet we did not directly test these associations. We did not have specific hypotheses about such relationships, and empirically examining these relationships was beyond our descriptive research goals. We encourage other scholars to develop and test specific hypotheses relating these work values to economic trends. Third, the MTF samples of high school seniors do not typically include individuals who drop out of high school, yet their expectations and constructions of work life are important as well. Future research should focus on this understudied and potentially vulnerable population. Finally, many aspects of work are unmeasured in this study, which particularly precludes a full understanding of the association between work and leisure time; indeed, a burgeoning body of research examines the social or fun nature of work itself (e.g., Carton, 2008). Future studies should further investigate the tensions between various work values to gain further understanding of the meanings adolescents place on work in relation to other domains.

Conclusions

Examining adolescents’ work values is a way to view work-related social and economic milieus through the eyes of adolescents. These constructed meanings shed light on the futures different groups of adolescents perceive as being available to them, and thus they are important for gaining a deeper understanding of the future work force from their perspectives. Adolescents’ values serve as a barometer for social change, and our findings overall suggest that work has declined in intrinsic significance for recent cohorts of youth. The decreasing meaning adolescents place on work suggests the potential need for institutionalized alternatives to help youth redefine their possible selves (Flanagan, 2005).

Furthermore, as a social constructivist approach suggests (e.g., Liebel, 2004), our findings documented that adolescents’ meanings of work vary by social location. During the transition to adulthood youth are increasingly vulnerable to economic risks (Settersten, 2005), with minority and socioeconomically disadvantaged youth even more vulnerable (Osgood et al., 2005). Future work should consider the extent to which differences in constructed meanings of work, formed both during and prior to adolescence, play a role in occupational differences or earning disparities later in life.

Currently (2008–2009), the U.S. is enduring a major economic recession that is carrying wide ranging difficulties throughout society. These problems, and the ongoing generation of attempted solutions (e.g., stimulus package, bailout of financial institutions) portend major, and potentially long-lasting, economic and social changes that current and recent cohorts of high school seniors will have to navigate. We should continue to chart adolescents’ work values as one window on the American government’s evolving social contract with its citizens.

Footnotes

This research was funded by The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on the Transition to Adulthood. The first and second authors’ time was supported by NIDA-funded National Research Service Awards (F31 DA 024543 and F31 DA 024916 respectively). The authors would like to thank Drs. James Coté, Ann Crouter, Jeremy Staff, Jerald Bachman, Lloyd Johnston, Patrick O’Malley, and John Schulenberg for their thoughtful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript and anonymous reviewers for their insights.

Specifically, we combined items to display them in figures when the items were similar in conceptual meaning and in patterns of trends over time. We assessed similarity of trends by computing correlations at the aggregate level (i.e., across cohort means), and considered trends similar for time trend correlations of .7 or higher. Item combinations match their use of work values items in previous research using MTF data (e.g., Johnson & Elder, 2002).

We examined the interaction between educational plans and the categorical effects of year in the generalized linear model with logit link. Before 1992, there were no significant differences between 2-year and no-college-plan groups on the work skills items. Also prior to 1992, only three years showed significant or marginally significant differences between 2-year and 4-year groups, with all differences indicating more support for these values among high school seniors with 2-year plans. Adolescents with 2-year plans were significantly or marginally higher on valuing work skills than those with no-plans in 10 out of 13 years and higher than those with 4-year plans in 9 out of these 13 years (p’s ≤ .10).

References

- Alwin DF, McCammon RJ. Generations, cohorts, and social change. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan M, editors. Handbook of the life course. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2003. pp. 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No. 64. Institute for Social Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 2006. The Monitoring the Future project after thirty-two years: Design and procedures. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel AM, Marini MM. Gender and values. American Sociological Review. 1995;40:358–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bills DB. Participation in work-related education: Variations in skill enhancement among workers, employers, and occupational closure. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2005;23:67–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone B, Rose S. Overworked and underemployed: Unraveling the economic enigma. The American Prospect. 1997;31:58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics Number of jobs held, labor market activity, and earnings growth among the youngest baby boomers: Results from a longitudinal survey. 2006a August; (USDL Publication No. 06–1496). Retrieved on January 28, 2007 from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/nlsoy.pdf.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics Employee tenure in 2006. 2006b September; (USDL Publication No. 06–1563). Retrieved on March 1, 2008 from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/history/tenure_09082006.txt.

- Carton E. Labor, leisure, and liminality: Disciplinary work at play. Leisure Studies. 2008;27:375–378. [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Easterlin RA, Saito Y. Preference changes among American youth: Family, work, and goods aspirations 1976–86. Population and Development Review. 1991;17:115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Danziger SH, Gottschalk P. Diverging fortunes: Trends in poverty and inequality. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RA, Crimmins EM. Private materialism, personal self-fulfillment, family life, and public interest: The nature, effects, and causes of recent changes in the values of American youth. The Public Opinion Quarterly. 1991;55:499–533. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Templeton J, Barber BL, Stone MR. Adolescence and emerging adulthood: The critical pathways to adulthood. In: Bornstein MH, Davidson L, Keyes CLM, Moore KA, The Center for Child Well-being, editors. Well-being: Positive development across the life course. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 386–406. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Evans K. Taking control of their lives? Agency in young adult transitions in England and the new Germany. Journal of Youth Studies. 2002;5:245–269. [Google Scholar]

- Farber HS. What do we know about job loss in the United States? Evidence from the Displaced Workers Survey, 1984–2004. FRB Chicago Economic Perspectives. 2005;29:13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Farber HS. Network on Transitions to Adulthood Policy Brief, December 2006, Issue 38. MacArthur Foundation Network on Transition to Adulthood and Public Policy; Philadelphia, PA: 2006. Is the company man an anachronism? Trends in long term employment in the U.S. between 1973 and 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez RM. Skill-biased technological change and wage inequality: Evidence from a plant retooling. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;107:273–320. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan CA. Developmental roots of political engagement. PS: Political Science and Politics. 2003a;6:257–261. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan CA. Trust, identity, and civic hope. Applied Developmental Science. 2003b;7:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan CA. Public scholarship and youth at the transition to adulthood. In: Eberly RA, Cohen J, editors. A laboratory for public scholarship and democracy. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2005. pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan CA. Private anxieties and public hopes: The perils and promise of youth in the context of globalization. In: Cole J, Durham D, editors. Figuring the future: Children, youth, and globalization. SAR Press; Santa Fe, New Mexico: 2008. pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell E, Furstenberg FF. The transition to adulthood during the 20th century: Race, nativity, and gender differences. In: Settersten R, Furstenberg F, Rumbaut R, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2005. pp. 29–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen KJ, Gergen MM. Social construction: Entering the dialogue. Taos Institute Publications; Chagrin Falls, OH: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gracie LW. Measurable outcomes of workforce development and the economic impact of attending a North Carolina community college. New Directions for Community Colleges. 1998;104:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan A. The critical role of education in the nation’s economy; Speech given at the Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce 2004 Annual Meeting; Omaha, NE. 2004, February 20; Retrieved online on January 15, 2007 from http://www.federalreserve.gov/boardDocs/Speeches/2004/200402202/default.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Hill MS, Yeung WJ. How has the changing structure of opportunities affected transitions to adulthood? In: Booth A, Crouter AC, Shanahan MJ, editors. Transitions to adulthood in a changing economy: No work, no family, no future? Greenwood; Westport, CT: 1999. pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart R. Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic and political change in 43 societies. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK. Change in job values during the transition to adulthood. Work and Occupations. 2001a;28:315–345. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK. Job values in the young adult transition: Change and stability with age. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2001b;64:297–317. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK. Social origins, adolescent experiences, and work value trajectories during the transition to adulthood. Social Forces. 2002;80:1307–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Elder GH. Educational pathways and work value trajectories. Sociological Perspectives. 2002;45:113–138. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM. In: Monitoring the Future: A continuing study of the lifestyles and values of youth. Conducted by University of Michigan, Survey Research Center; ICPSR, editor. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 2006. (12th- Grade Survey), 1976–2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK, Harvey S. Learning to work: The development of work beliefs. In: Barling J, Kelloway EK, editors. Young workers: Varieties of experience. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1999. pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann W. “For some reason, I get a little scared”: Structure, agency and risk in school-work transitions. Journal of Youth Studies. 2004;4:379–396. [Google Scholar]

- Liebel M. A will of their own: Cross-cultural perspectives on working children. Zed Books; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MH, Marcelo KB. Youth demographics. Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement; College Park, MD: Nov, 2006. CIRCLE Fact Sheet. [Google Scholar]

- Mannheim K. The problem of generations. In: Kecskemeti P, editor. Essays on the sociology of knowledge by Karl Mannheim. Routledge; New York: 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte DE. Has job stability declined? Evidence from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 1999;58:189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Marini MM, Fan P, Finley E, Beutel AM. Gender and job values. Sociology of Education. 1996;69:49–65. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishel L, Bernstein J, Allegretto S. The State of Working America 2006/2007. 2007 Economic Policy Institute Report. Retrieved on July 1, 2007 from http://www.stateofworkingamerica.org.

- Mollenkopf J, Kasinitz P, Waters M. The ever-winding path: Transitions to adulthood among native and immigrant young people in metropolitan New York. In: Settersten RA, Furstenberg FF Jr., Rumbaut RG, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2005. pp. 454–497. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Holmes M, Shanahan M. The process of occupational decision making: Patterns during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2002;61:439–465. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood W, Foster EM, Flanagan CA, Ruth G, editors. On your own without a net: The transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Phillippe KA. Fourth Edition Community College Press, American Association of Colleges; Washington, DC: 2005. National profile of community colleges: Trends and statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone. Simon & Schuster, Inc; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J, Stewart M, McDonald R, Sischo L. Have adolescents become too ambitious? High school seniors’ educational and occupational plans, 1976–2000. Social Problems. 2006;53:186–206. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach M. The nature of human values. Free Press; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder NB. The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review. 1965;30:843–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B, Stevenson D. The ambitious generation. Educational Leadership. 1999;57:22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. Historical trends in attitudes and preferences regarding family, work, and the future among American adolescents: National data from 1976 through 1992. Institute for Social Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 1994. Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA. Social policy and the transition to adulthood. In: Settersten RA, Furstenberg FF, Rumbaut RG, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2005. pp. 534–560. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA, Furstenberg FF, Rumbaut RG. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vondracek FW, Porfeli EJ. The world of work and careers. In: Adams GR, Berzonsky MD, editors. Blackwell handbook of adolescence. Blackwell Publishing; Malden, MA: 2003. pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]