Abstract

Introduction

Intestinal endometriosis is often an infrequently considered diagnosis in female of childbearing age by general surgeon. There is a delay in diagnosis because of constellation of symptoms and lack of specific diagnostic modalities. Patients suffer from intestinal endometriosis for many years before they are diagnosed. Often, such patients are labelled with irritable bowel syndrome. Intestinal endometriosis has a diagnostic time delay of 8–11 years due to its non-specific clinical features and multi-system involvement.

Presentation of Case

Our patient was a 32 years old Caucasian female who was referred to us with features of intestinal obstruction. Despite repeated clinical assessments and use of different diagnostic modalities the diagnosis was still inconclusive even after 21 days of her first presentation to primary care physician. She had an exploratory laparotomy, sigmoid colectomy, and Hartmann's procedure with a temporary colostomy with us. Histopathology confirmed endometriosis and also showed melanosis coli. She was referred to the gynaecological team for review and follow up.

Discussion

Intestinal endometriosis should be considered as a differential diagnosis in female patients of childbearing age group presenting with non-specific gastrointestinal signs and symptoms. Our patient manifested intestinal endometriosis and melanosis coli on histopathology suggesting symptoms of long duration.

Conclusion

Bowel endometriosis is a less considered and often ignored differential diagnosis in acute and chronic abdomen. This condition has considerable effect on patient's health both physically and psychologically.

Abbreviations: bpm, beats per minutes; CA-125, tumour marker for ovarian carcinoma; cm, centimetre; COCPs, combined oral contraceptive pills; CRP, C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker; CT scan, computerised tomographic scan; e.g., an abbreviation for the Latin phrase exempli gratia. When you mean “for example,” use e.g.; g, gram; g/dl, gram per decilitre; GnRH, gonadotropic releasing hormone; L, litre; mg, milligram; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NSAIDs, non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; WBC, white blood cell; %, percentage

Keywords: Sigmoid endometriosis, Melanosis coli, Large bowel, Obstruction, Gastroenteritis, Colonoscopy, Hartmann's procedure

1. Introduction

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of functioning endometrial like tissue outside mucosal lining of the uterus. It is a benign gynaecological condition, affecting women in childbearing age, which usually causes relatively mild cyclical symptoms related to her menstrual periods.

Colonic obstruction occurs secondary to cancer, complicated diverticular diseases or volvulus in approximately 90% of patients. Other conditions like adhesions, ulcerative colitis, radiation enteritis, faecal impaction, foreign bodies, pseudo-obstruction, inflammatory strictures, obstructed hernia and endometriosis with other rare conditions make up for rest of 10%.1

In this article we report a case of large bowel obstruction secondary to sigmoid endometriosis, which led to a diagnostic challenge (Figs. 1–4).

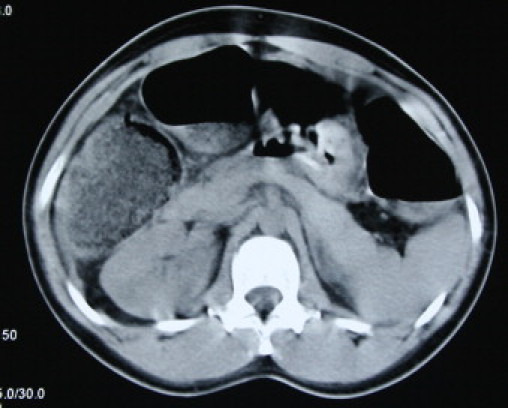

Fig. 1.

Non-Contrast CT scan, showing dilated bowel loops.

Fig. 2.

Non-contrast CT scan, showing dilated loaded colon in pelvis with no obstructing lesion.

Fig. 3.

PFA showing small and large bowel loops with feacal loading and air upto distal colon.

Fig. 4.

Histological film showing endometrial gland in with stromal tissue.

2. Case presentation

2.1. Presentation and history

A 32 years old nulliparous, Caucasian woman with history of diahorrea for the previous 3 weeks who had been managed as gastroenteritis by her primary care physician. She was admitted to her local hospital with a history of moderate to severe generalised abdominal pain, vomiting and dark coloured stools. She was investigated with chest X-ray, abdominal X-ray and colonoscopy. She was managed conservatively and also had a non-contrast abdominal – pelvic CT scan demonstrated dilated loops of small and large bowels (Figs. 1–3).

She was referred to our regional hospital with above history. Her complaints, abdominal pain, abdominal distension aggravated for last 24 h and developed absolute constipation. Her systemic review and past medical history was unremarkable.

2.2. Physical examination and laboratory investigations

She was afebrile and haemodynamically stable on presentation. Her abdomen was grossly distended, diffusely tender and tympanatic on percussion with high-pitched bowel sounds.

The patient's laboratory results revealed haemoglobin of 12.5 g/dl, which dropped to 10.9 g/dl next day. Her leukocyte count was 9.7 × 109/L with moderate neutrophilia. Biochemistry laboratory results were within normal range but with raised CRP level of 64.4 g/L.

She under went an exploratory laparotomy after resuscitation and with informed consent through infraumblical midline incision. There was a firm irregular suspicious looking tumour measuring approximately 3 cm × 4 cm in distal sigmoid colon adherent to sacrum. A sigmoid colectomy with Hartmann's procedure was performed and temporary colostomy fashioned in left iliac fossa. She had an uneventful recovery. She was discharged home with future plan for early reversal of colostomy. Her histopathology confirmed intestinal endometriosis not involving mucosa (Fig. 4). Melanosis coli was also noted that correlates well with prolonged use laxatives for constipation.

She was re-admitted within 10 days of her initial operation with lower abdominal pain and raised WBC count of 13.5 × 109/L. She had CT scan to rule out intra-abdominal collection that did not show any discrete collection. She settled with intravenous antibiotics. She was seen by gynaecologist and commenced on Injection Decapeptyle, 3 mg intramuscular on monthly basis.

She had reversal of Hartmann's 9 weeks after her initial surgery. She was discharged from surgical outpatients’ clinics after 8 weeks to continue follow up with gynaecologist.

3. Discussion

Intestinal endometriosis mostly occurred in nulliparous women of childbearing age. Such patients suffer from non-specific colonic symptoms or either asymptomatic and this can account for underestimation of this disease.1,4 The incidence of bowel involvement with endometriosis had been variable 3–34%. Colonic involvement had been reported in 12–25% of patients with endometriosis. The most frequent location of endometrial implants were the recto-sigmoid junction (72%) followed by small intestine (7%) ceacum (3.6%) and appendix (3%) MacAfee et al. Endometrial implants had also been reported in urinary bladder, kidneys, skin, umbilicus, perineum, lungs, CNS and striated muscles. The median age at the time of diagnosis was 34–40 years.1,2,3 Endometriosis had also been noted in postmenopausal women in few studies.6

The etiology of endometriosis is still elusive and three theories are prevalent. Firstly, Sampson's theory of transplantation and implantation is vastly accepted and well supported since 1920 based on observation retrograde menstruation noted in 76–90%. Secondly, Meyer's theory of ceolomic metaplasia this explains presence of endometriosis in men and postmenopausal women. This is based on common origin of endometrium and peritoneum from common embryonic precursor cells. Third is Halban's theory, suggests that distant lesion is mostly due haematogenous and lymphogenous spread.5

The hypothesised mechanism leading to bowel obstruction is that the ectopic endometrial tissue or implant respond to ovarian hormones on cyclical basis leading to inflammation, fibrosis, and metaplasia or hyperplasia of intestinal smooth muscles that can involve serosa, submucosa and uncommonly mucosa.7 This point can lead to intussception, volvulus or mechanical kinking of bowel as we believe in our patient.

Clinical symptoms range from asymptomatic to constellation of symptoms like painful bowel movements, cramps, constipation, diarrhoea, vomiting, rectal pain, infertility, abdominal mass, increased urinary frequency and cyclical hematochezia.6

Cyclical hematozachia, this was also present in our patient, had been seen even without mucosal involvement as this was noted in menopausal women as well. The frequent absences of intramural haemorrhage suggest that intestinal endometric deposits do not always menstruate or bleed. This can be explained as secondary to transient mucosal tear which is caused by extensive oedema and swelling of underlying endometrial deposits under hormonal influence.6,8,9

A thorough history and high index of suspicion are prerequisites to reach such diagnoses. Recto-vaginal examinations showed marked limitations despite the controlled circumstances. This can lead to variable differential diagnosis including irritable bowel syndrome, diverticulitis, appendicitis, Crohn's disease, tubo-ovarian abscess, lymphoma, and carcinoma. In a case report it mimicked solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.10 Different radiological imaging techniques did not show any specific signs though endorectal ultrasound with radial probe had shown high specificity and sensitivity.11 Recently dynamic contrast – enhanced MRI had shown improved results. These results were presented in 9th World Congress on Endometriosis, September 2005.12 Colonoscopy had not to be proven a helpful diagnostic tool as in our case as well but it is still recommended in all patients with suspected endometriosis to rule out mucosal involvement and malignant lesions with help of biopsies, if needed. Histopathological confirmation required presence of both glandular and stromal tissue. Laparoscopy offers the best and definitive diagnostic opportunity for this disease. It has overall sensitivity of 97% and despite it's invasiveness has specificity of only 77%.13,14 CA-125 can be useful marker for monitoring the treatment with limited diagnostic value.

Treatment of endometriosis is generally medical for its symptoms and disease control. This includes use of NSAIDs and COCPs (combined oral contraceptive pills) as first line of treatment especially for deep pelvic pain. GnRH-agonist and gonadotropic hormone inhibitors, e.g. Danzol are used as second line of defence. Their long-term use is not established and limited due their side effects. These can be used with Add back therapy with COCPs. Aromatise inhibitors and iron chelators have also been used in deep and early endometriosis respectively. Exeresis may be necessary after failed medical management and stays the primary treatment for colonic involvement especially in obstruction or when diagnosis in doubt. This can range from local excision of lesion to an anterior resection dictated by clinical picture and complemented by hormonal treatment, as in our patient.15 Endoluminal stenting for relief of colonic obstruction has been shown as safe and effective option.

4. Conclusion

Intestinal endometriosis is an under diagnosed condition with high morbidity and psychosocial implications. This can be extremely difficult to diagnose preoperatively due to constellation of symptoms and non-availability of specific investigations. Surgery plays major role in management and diagnosis as this can be challenging. So, endometriosis should be considered in differential diagnosis in females of all ages especially of child bearing age group with unexplained bowel symptoms and thus their management be tailored.

We report our case of sigmoid endometriosis and melanosis coli causing colonic obstruction. This was her first presentation and turned out to be a diagnostic challenge.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

It is to confirm that patient has given an informed consent to publish her case and histopathological pictures.

Contributions

HN managed patient on arrival and initiated treatment and looked after patient throughout. Performed surgery under direct supervision. Did literature search and referencing and submitted after writing it. DS contributed in pre and post operative care of patient and helped in writing paper. AN has supervised the care of the patient as Consultant. He also helped in drafting, critically analysing and proof reading the document.

Contributor Information

H. Nasim, Email: humair_nasim@yahoo.ie.

D. Sikafi, Email: dsikafi@gmail.com.

A. Nasr, Email: arhnasr@eircom.net.

References

- 1.Kupersmith J.E.E., Catania J.J., Patil V., Herz B.L. Large bowel obstruction and endometriosis. Hosp Physician. 2001;(July):46–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimoulios P., Koutroubakis I.E., Tzardi M., Antoniou P., Matalliotakis I.M., Kouroumalis E.A. A case of sigmoid endometriosis difficult to differentiate from colon cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2003;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh K.K., Lessells A.M., Adam D.J., Jordan C., Miles W.F., Macintyre I.M. Presentation of endometriosis to general surgeons: a 10-year experience. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1349–1351. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800821017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Endometriosis still takes 8 years to diagnose- and treatment options…www.endometriosis.org/press15septemper05.html.

- 5.Pritts EA, Taylor RN. Endometriosis [chap. 9], www.endotext.org.

- 6.Kazadi B.J., Alcazar J.L., Laparte M.C., Lopez G.G. Catamenial rectal bleeding and sigmoid endometriosis. J Gynecol Obstet Bio Rep. 1992;21(7):773–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itoga T., Matsumoto T., Takeuchi H., Yoshiyama H., Nishikawa J., Nakamura H. Fibrosis and smooth muscle metaplasia in rectovaginal endometriosis. Path Int. 2003;53(June (6)):371–375. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2003.01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levitt M.D., Hodby K.J., van Merwyk A.J., Glancy R.J. Cyclical rectal bleeding in colorectal endometriosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1989;59(December (12)):941–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1989.tb07635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham B., Mazier W.P. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis of colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31(December (12)):952–956. doi: 10.1007/BF02554893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daya D., O’Connell G., DeNardi F. Rectal endometriosis mimicking solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Mod Pathol. 1995;8(August (6)):599–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrao M.S., Neme R.M., Averbach M. Rectal endoscopic ultrasound with a radial probe in assessment of rectovaginal endometriosis. J Am Assoc Gynec Lapar. 2004;11(February (1)):50–54. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hummelshoj L, Pretice A, Groothius P. Update on endometriosis. www.endometriosis.org/WCEupdate.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kennedy S., Bergqvist A., Chapron C., D’Hooghe T., Dunselman G., Greb R. ESHRE guideline on diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(10):2698–2704. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchweitz O., Poel T., Diedrich K. The diagnostic dilemma of minimal and mild endometriosis under routine conditions. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(1):85–89. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nezahat C., Nezahat F., Pennington E. Laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative…CO2 laser. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;(August (8)):664–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]