Abstract

Spigelian hernia is a rare hernia of the ventral abdominal wall accounting for 1–2% of all hernias. Incarceration of a Spigelian hernia has been reported in 17–24% of the cases. We herein describe an extremely rare case of a colonic obstruction secondary to an incarcerated Spigelian hernia in a severely obese patient. Physical examination was inconclusive and diagnosis was established by computed tomography scans. The patient underwent an open intraperitoneal mesh repair. A high level of suspicion and awareness is required as clinical findings of a Spigelian hernia are often nonspecific especially in obese patients. Computed tomography scan provides detailed information for the surgical planning. Open mesh repair is safe in the emergent surgical intervention of a complicated Spigelian hernia in severely obese patients.

Keywords: Spigelian hernia, Incarceration, Colon obstruction

1. Introduction

Spigelian hernia (SH) is the protrusion of preperitoneal fat, peritoneal sac or abdominal viscera through the spigelian aponeurosis, which is an aponeurotic layer bounded by the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle medially and the semilunar line laterally.1,2 Although the semilunar line was first described by the Belgian anatomist Adriaan van der Spieghel in 1645, it was Josef Klinkosch in 1764 who first reported hernias protruding through this area and named them Spigelian line hernias.1 Since then, more than 1000 cases have been reported in the literature.3 We herein describe an extremely rare case of a colonic obstruction secondary to an incarcerated SH in a severely obese patient. To our knowledge, this is the seventh case reported in the English literature.

2. Presentation of case

A 41-year-old severely obese man presented with a 6-day history of right lower abdominal pain, abdominal distension and progressive constipation. His past medical history included a right lower paramedian laparotomy for a perforated appendix and a laparoscopic gastric banding that was performed 3 months prior to the current admission. During these 3 months he had experienced a 30 kg weight loss.

On examination his weight was 140 kg with a body mass index of 44.2 kg/m2. Physical examination revealed abdominal distension with intermittent hyperactive bowel sounds whereas an ill-defined tender mass was hardly palpable in the right lower abdomen. Laboratory investigations showed mild leucocytosis at 12.5 × 109/L. Plain abdominal radiograph showed dilated small bowel loops with gas-fluid levels. A subsequent CT scan revealed characteristic findings of a right Spigelian hernia (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen showing a large Spigelian hernia with incarcerated colon, small bowel and omentum. Note the excessive thickness of the subcutaneous fat layer.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen showing a large Spigelian hernia with incarcerated colon, small bowel and omentum. Note the wide hernia neck (arrow).

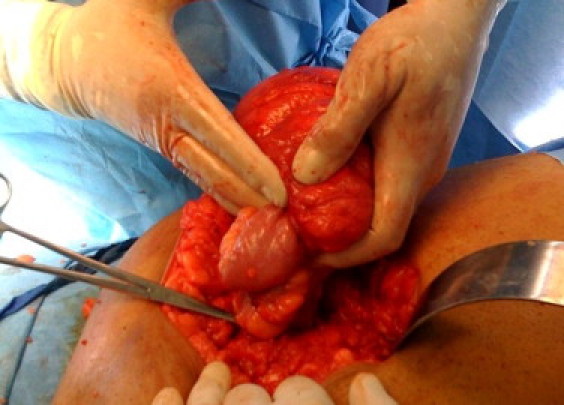

Surgical exploration was carried out through a right paramedian incision placed over the hardly palpable mass. After the external oblique aponeurosis was opened a large hernia sac was found containing incarcerated ascending colon, a small bowel loop and a portion of greater omentum (Fig. 3). All the incarcerated hernial sac contents were viable and were then reduced into the abdominal cavity. The hernial defect was well edged and measured approximately 4 × 5 cm. The hernia was repaired with the use of an intraperitoneal dual mesh. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged home on the second postoperative day. He remains well without any evidence of hernia recurrence 12 months after surgery.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative photo showing the large hernia sac with the incarcerated contents.

3. Discussion

SH is in the vast majority of the cases an acquired entity.4 It most commonly affects patients in the sixth decade of life with a slight male preponderance.4,5 Although it may occur anywhere along the spigelian aponeurosis, in 90% of the cases occurs within a 6-cm area distal to the umbilicus where the spigelian aponeurosis is widest.4 Various predisposing factors have been reported to be associated with the development of SH such as obesity, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, multiple pregnancies, previous surgery, previous laparoscopy and rapid weight loss.2 In our patient, obesity, previous laparotomy and laparoscopy likely resulted in the weakening of the semilunar line and subsequent large Spigelian hernia formation.

Clinical presentation of patients with SH depends on the size and hernial sac contents. Patients most commonly present with an intermittently palpable mass and or postural pain.4,5 Incarceration has been reported in 17–24% of the patients5,6 whereas in 10% of the cases an emergent surgical intervention is required.5 More than one third of the patients lack an abdominal mass or defect on clinical examination.5 Small hernias can be masked by the subcutaneous fat and the intact external oblique aponeurosis especially in obese patients.6 In many cases, however, symptoms and signs are no specific thus resulting in delay in diagnosis.

Ultrasonography and CT scans are useful in the diagnostic evaluation, with a reported sensitivity of 83% and 100% respectively.4 The presence of obesity limits the sensitivity of ultrasonography. CT however can provide detailed information about the anatomy of the area and hernia contents allowing a direct approach to the hernia sac thus avoiding an unnecessary laparotomy.3

Hernia sac consists of extraperitoneal fat and peritoneum with or without splachnic contents. Various organs have been reported as contents of a SH such as small bowel, omentum colon, stomach, gallbladder, ovaries and testes.1 Our case of colonic obstruction secondary to an incarcerated Spigelian hernia is extremely rare with only six cases reported in the English literature since 1960.3,7

Differential diagnosis of SH includes other abdominal wall hernias, rectus sheath hematoma, tumors of the abdominal wall and various intra-abdominal tumors or inflammatory disorders. The hernia defect is usually small (less than 2 cm) with well-defined edges.2 Because of the narrow hernia neck SH is usually small but is prone to strangulation and irreducibility.1

Due to strangulation risk surgical repair of SH is mandatory.4,5 Repair can be performed via an open or laparoscopic approach. In a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing 11 conventional and 11 laparoscopic SH repairs it was found that extraperitoneal laparoscopic approach was associated with significantly lower morbidity and shorter hospital stay.8 None of the patients of either series had hernial incarceration. The authors however recommended anterior hernioplasty in cases of complication or emergency.8 In our patient who was severely obese with a history of previous laparotomy in the presence of multivisceral incarceration we believe that open repair was the most appropriate approach. After surgical repair long term outcome is excellent with a very low recurrence rate.4,7

4. Conclusions

Colonic obstruction secondary to an incarcerated SH is an extremely rare occurrence. A high level of suspicion and awareness is required as clinical findings of a SH are often non-specific especially in obese patients. CT scan can delineate in detail the anatomy and the hernia sac contents thus providing useful information for the surgical planning. Open SH repair is safe in the emergent surgical intervention for a complicated Spigelian hernia in severely obese patients.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

There are no sources of funding.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

References

- 1.Skandalakis P.N., Zoras O., Skandalakis J.E., Mirilas P. Spigelian hernia: surgical anatomy, embryology, and technique of repair. Am Surg. 2006;72:42–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salameh J.R. Primary and unusual abdominal wall hernias. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller R., Lifschitz O., Mavor E. Incarcerated Spigelian hernia mimicking obstructing colon carcinoma. Hernia. 2008;12:87–89. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vos D.I., Scheltinga M.R. Incidence and outcome of surgical repair of spigelian hernia. Br J Surg. 2004;91:640–644. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson D.W., Farley D.R. Spigelian hernias: repair and outcome for 81 patients. World J Surg. 2002;26:1277–1281. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spangen L. Spigelian hernia. World J Surg. 1989;13:573–580. doi: 10.1007/BF01658873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Losanoff J.E., Jones J.W., Richman B.W. Recurrent Spigelian hernia: a rare cause of colonic obstruction. Hernia. 2001;5:101–104. doi: 10.1007/s100290100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreno-Egea A., Carrasco L., Girela E., Martin J.G., Aguayo J.L., Canteras M. Open vs laparoscopic repair of spigelian hernia: a prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1266–1268. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.11.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]