Abstract

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter with broad functions in brain development, neuronal activity, and behaviors; and serotonin is the prominent drug target in several major neuropsychiatric diseases. The multiple actions of serotonin are mediated by diverse serotonin receptor subtypes and associated signaling pathways. However, the key signaling components that mediate specific function of serotonin neurotransmission have not been fully identified. This review will provide evidence from biochemical, pharmacological, and animal behavioral studies showing that serotonin regulates the activation states of brain glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) via type 1 and type 2 serotonin receptors. In return, GSK3 directly interacts with serotonin receptors in a highly selective manner, with a prominent effect on modulating serotonin 1B receptor activity. Therefore, GSK3 acts as an intermediate modulator in the serotonin neurotransmission system, and balanced GSK3 activity is essential for serotonin-regulated brain function and behaviors. Particularly important, several classes of serotonin-modulating drugs, such as antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics, regulate GSK3 by inhibiting its activity in brain, which reinforces the importance of GSK3 as a potential therapeutic target in neuropsychiatric diseases associated with abnormal serotonin function.

Keywords: serotonin, GSK3, 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2A, antidepressants

Serotonin Neurotransmission

Serotonin

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) is a monoaminergic neurotransmitter that is synthesized from the amino acid tryptophan. Serotonergic neurons arise from the raphe nucleus of the brain stem, and they project upward to most areas of the brain and downward to peripheral nerve terminals. Upon release, 5-HT in the synapse is recycled by reuptake through the 5-HT transporter (5-HTT) and is catabolized by monoamine oxidase (MAO). There are at least 7 families and 14 subtypes of 5-HT receptors that are classified by their sequence homology and associated type of G-proteins and signal transduction pathways (Hoyer and Martin, 1997; Bockaert et al., 2006; Table 1). Among these 5-HT receptors, the type 1 (5-HT1) and the type 2 (5-HT2) receptors are the most studied, with rich literatures showing their roles in brain function and diseases (Hannon and Hoyer, 2008).

Table 1.

Serotonin receptors.

| Family | Subtypes | Classical signal transduction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1 | 1A, 1B, 1D, 1E, 1F | Gi/Go-protein coupled | Inhibit AC, reduce cAMP, inhibit PKA |

| 5-HT2 | 2A, 2B, 2C | Gq/G11-protein coupled | Increase IP3, increase intracellular calcium, increase DAG, activate PKC |

| 5-HT3 | Ligand-gated Na+ and K+ cation channel | Membrane depolarization | |

| 5-HT4 | Gs-protein coupled | Activate AC, increase cAMP, activate PKA | |

| 5-HT5 | 5A, 5B | Gi/Go-protein coupled | Inhibit AC, reduce cAMP, inhibit PKA |

| 5-HT6 | Gs-protein coupled | Activate AC, increase cAMP, activate PKA | |

| 5-HT7 | Gs-protein coupled | Activate AC, increase cAMP, activate PKA | |

Serotonin type 1A (5-HT1A) receptors

5-HT1A receptors are the prototypical 5-HT1 receptors. In addition to coupling to the inhibitory G-protein (Gi) that inhibits adenylyl cyclase, decreases cyclic AMP (cAMP) production, and inactivates protein kinase A (PKA; De Vivo and Maayani, 1986), studies in neurons reveal that 5-HT1A receptors also regulate other protein kinases, such as growth factor-associated Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinases (Erk; Cowen et al., 1996, 2005). 5-HT1A receptors are widely distributed in major brain areas including the dorsal raphe nucleus, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, striatum, and nucleus accumbens (Varnas et al., 2004). In 5-HT neurons, 5-HT1A autoreceptors are located in the cell bodies and somatodendrites, and activation of these receptors reduces neuron firing and suppresses 5-HT release (Riad et al., 2000). In non-serotonergic neurons, 5-HT1A heteroreceptors are found in both pre- and post-synaptic locations (Hoyer et al., 2002). Depending on the location and associated neurons, activation of 5-HT1A heteroreceptors modulates neurotransmission of glutamate, GABA, norepinephrine, and acetylcholine (Fink and Gothert, 2007), generally causing inhibition of long-term potentiation (Edagawa et al., 1998; Tachibana et al., 2004), increased axonal and dendritic branching (Yan et al., 1997), and postnatal neurogenesis (Banasr et al., 2004). 5-HT1A receptors mediate many behavioral effects of 5-HT, particularly those related to mood and anxiety (Kennett et al., 1987; Parks et al., 1998).

Serotonin type 1B (5-HT1B) receptors

The rodent 5-HT1B receptors and its human homolog 5-HT1D receptors share high protein sequence homology and signal transduction processes with 5-HT1A receptors, and 5-HT1B receptors also act as both autoreceptors and heteroreceptors in the brain (Bouhelal et al., 1988; Hoyer and Martin, 1997; Leone et al., 2000; Bockaert et al., 2006). Different from 5-HT1A autoreceptors, 5-HT1B autoreceptors are primarily located on the 5-HT neuron axon terminals that extend to other brain regions. Upon activation, 5-HT1B autoreceptors cause a strong feedback inhibition of 5-HT release (Riad et al., 2000). 5-HT1B receptors also act as heteroreceptors in several brain regions to control release of other neurotransmitters (Sari, 2004). Both 5-HT1B receptor agonists and antagonists may have antidepressant effects; blocking autoreceptors increases extracellular 5-HT which enhances the effect of serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (Dawson et al., 2006), whereas activation of heteroreceptors contributes to an antidepressant effect, potentially through their effects on dopaminergic neurotransmission (Chenu et al., 2008). Recently, 5-HT1B receptors have been found to interact with an intracellular adaptor protein p11 (Svenningsson et al., 2006), which regulates 5-HT1BR activity and stability, and deletion of which causes depression-like behaviors in animals (Svenningsson and Greengard, 2007).

Serotonin type 2A (5-HT2A) receptors

5-HT2A receptors are the prototypical type 2 5-HT receptors that couple to Gq protein to activate phospholipase C (PLC) and its down-stream targets such as protein kinase C (PKC; Conn and Sanders-Bush, 1984; Roth et al., 1986; Takuwa et al., 1989). 5-HT2A receptors have also been reported to activate Akt and Erk (Watts, 1998; Johnson-Farley et al., 2005; Zhong et al., 2008), although the receptor-coupling mechanism of this regulation is not completely understood. 5-HT2A receptors also couple to the intracellular scaffolding protein β-arrestin2, which may have unique functions to initiate desensitization of 5-HT2A receptors and to direct ligand-selective signal transduction processes (Schmid et al., 2008; Schmid and Bohn, 2010). 5-HT2A receptors are expressed throughout the brain, most prominently in the cerebral cortex, striatum, and hippocampus (Bockaert et al., 2006), where they are located on soma, dendrites, and axons of pyramidal neurons, interneurons, and monoaminergic neurons (Jakab and Goldman-Rakic, 1998; Cornea-Hebert et al., 1999; Hoyer et al., 2002; Miner et al., 2003). Activation of 5-HT2A receptors modulates levels of other neurotransmitters, such as causing inhibitory control over dopamine release (Schmidt and Fadayel, 1995). In many studies, 5-HT2A receptors are found to counteract the physiological and behavioral effects of 5-HT1A receptors (Marek et al., 2003). For example, Yuen et al. (2008) reported that activation of 5-HT2A/C receptors in prefrontal cortical neurons significantly attenuates the effect of 5-HT1A receptors on NMDA currents and microtubule depolymerization. 5-HT2A receptors have a different behavioral profile as 5-HT1A receptors. Most notably, a group of 5-HT2A receptor agonists are hallucinogens (Nichols, 2004), but 5-HT2A receptors also have significant effects in regulating other neuropsychiatric behaviors, such as mood, cognition, and sleep (Landolt and Wehrle, 2009).

Therapeutic implications of 5-HT modulators

For decades, modulation of 5-HT neurotransmission has been the primary pharmacological target for the treatment of major neuropsychiatric diseases, particularly depression and anxiety. The monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) enhance 5-HT neurotransmission by blocking 5-HT metabolism (Youdim and Bakhle, 2006), while tricyclic antidepressants (TCA; Klerman and Cole, 1965), serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) all enhance synaptic 5-HT action by blocking reuptake of 5-HT. Global enhancement of serotonin neurotransmission may activate all subtypes of serotonin receptors in brain, while each 5-HT receptor subtype has different and specific functions in defined brain regions. Activation of 5-HT1A receptors is thought to contribute to the effect of antidepressants in regulating mood and anxiety (Parks et al., 1998; Ramboz et al., 1998; Leonardo and Hen, 2008; Akimova et al., 2009; Savitz et al., 2009; Polter and Li, 2010; Price and Drevets, 2010), whereas acute activation-induced down-regulation of 5-HT1A autoreceptors may be necessary for the antidepressant and anxiolytic effects during long-term 5-HT reuptake inhibitor treatment (Blier and Ward, 2003; Albert and Lemonde, 2004). The specific roles of other 5-HT receptor subtype in the antidepressant action remain to be largely unknown.

In addition to enhancing 5-HT neurotransmission for treatment of anxiety and depression, agents with 5-HT2A receptor antagonistic property appear to have a unique role in treating neuropsychiatric diseases. Several antidepressants, including mirtazapine, nefazodone, and trazodone have 5-HT2A receptor antagonistic properties that may contribute to their unique antidepressant effect. Atypical antipsychotics not only are antagonists of dopamine D2 receptors (as with the conventional antipsychotics), but they also block 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors (Meltzer et al., 1989; Markowitz et al., 1999). In addition to treating psychosis, most atypical antipsychotics have indications for bipolar mania, and some have shown efficacy in ameliorating symptoms of depression (Tohen et al., 2003; Calabrese et al., 2005; Berman et al., 2007; Marcus et al., 2008; Bauer et al., 2009). Although the exact mechanism remains to be unknown, facilitating dopamine and norepinephrine neurotransmission (Schmidt and Fadayel, 1995; Zhang et al., 2000) and/or enhancing 5-HT1A receptor action (Marek et al., 2003) may contribute to this therapeutically relevant action of 5-HT2A receptor antagonists.

The brain’s serotonergic system is highly complex, in part due to its diffusely distributed multiple receptor subtypes and the signal transduction pathways regulated by these receptors. Therefore, identifying intracellular signaling molecules that direct 5-HT-regulated signals to specific physiological and behavioral effects may facilitate our understanding of brain 5-HT function and its role in neuropsychiatric diseases. Below we review current findings on the interrelationship between 5-HT and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3), with an emphasis on the type 1 and type 2 5-HT receptors.

Effects of 5-HT on Regulating GSK3

5-HT regulates GSK3 by phosphorylation

5-hydroxytryptamine was first found to regulate GSK3 in mouse brain. When wild type mice received an acute administration of d-fenfluramine, a drug that enhances 5-HT release and blocks 5-HT reuptake, phosphorylation of GSK3β at serine-9 residue was significantly increased in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and striatum (Li et al., 2004). Phosphorylation of this residue transforms the N-terminal of GSK3 into a pseudosubstrate which blocks other GSK3 substrates from entering the active site of the enzyme, thus, d-fenfluramine treatment results in inhibition of GSK3β in the brain. However, even in the presence of a MAOI that blocks the metabolism of 5-HT, the effect of a single intraperitoneal injection of d-fenfluramine is transient, peaking at 1 h, and gradually returning to baseline level by 4 h. This could be due to rapid metabolism of the drug in mice, but rapid release of 5-HT may cause negative feedback inhibition of 5-HT release as well as 5-HT receptor desensitization; both may also contribute to the transient effect of d-fenfluramine on GSK3 phosphorylation.

The inhibitory control of GSK3 by 5-HT is further demonstrated by an elegant study (Beaulieu et al., 2008b) in a mouse model where mice carry a mutation in the tryptophan hydroxylase-2 (TPH-2) gene that is equivalent to a rare human variant (R441H) identified in a few individuals with major depressive disorder (Zhang et al., 2005). The homozygous mutant mice, when compared to littermate wild type mice, have significantly lower levels of the 5-HT precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), 5-HT, and its metabolite 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in the frontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum. Meanwhile, the level of phosphorylated serine-9 of GSK3β is significantly lower, and GSK3 activity is elevated in the same brain regions of the mutant mice (Beaulieu et al., 2008b). Therefore, a sustained deficiency of 5-HT may reset the activity level of GSK3 in brain to higher level, compared to wild type mice where the constitutively active GSK3 is likely under inhibitory regulation (Doble and Woodgett, 2003). The overactive GSK3 in the R441H mutant mice may be involved in the behavioral abnormalities of these mice, since the depressive- and anxiogenic-like behavioral phenotypes of these mice were largely reversed by a GSK3 inhibitor, and by genetically reducing the level of GSK3β.

Behavioral significance of GSK3 regulation by 5-HT

Regulation of GSK3 by 5-HT may have functional significance in maintaining brain physiology and behaviors that are regulated by serotonergic neurotransmission. The 5-HT reuptake inhibitor antidepressant fluoxetine has been shown to increase phospho-Ser9-GSK3β in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, striatum, and cerebellum of mouse brain (Li et al., 2004, 2007; Beaulieu et al., 2008b) and phospho-Ser21-GSK3α in the hippocampus (Polter et al., 2011). Several studies also suggest that inhibition of GSK3β is an important intermediate step in the antidepressant effect of fluoxetine. In the TPH-2 mutant mice, abnormal behavior associated with 5-HT deficiency is mediated by GSK3β (Beaulieu et al., 2008b). Additionally, inhibition of GSK3 by small molecule inhibitors or in GSK3β-deficient mice have been shown to reduce immobility in the forced swim test (Gould et al., 2004; Kaidanovich-Beilin et al., 2004; O’Brien et al., 2004; Beaulieu et al., 2008a; Rosa et al., 2008), similarly to the antidepressants fluoxetine (Page et al., 1999; Bianchi et al., 2002). We have recently tested this behavioral effect of fluoxetine in mutant GSK3 knock-in (KI) mice in which serine-9 of GSK3β or serine-21 of GSK3α was substituted with alanine (S9A-GSK3β-KI and S21A-GSK3α-KI; McManus et al., 2005; Polter et al., 2010). These mice have normal levels of GSK3β and GSK3α, but the N-terminal serine cannot be regulated by phosphorylation. In the forced swim test (Porsolt et al., 1977) the baseline immobility (saline treatment) was not significantly different between S9A-GSK3β-KI, S21A-GSK3α-KI, and littermate wild type mice. As expected, wild type mice responded to fluoxetine (20 mg/kg, i.p., 30 min) with a significant 56% reduction in immobility when compared to saline-treated mice. However, the anti-immobility effect of fluoxetine in S9A-GSK3β-KI mice was markedly diminished, with only 17% non-significant reduction of immobility (Polter et al., 2011). Although fluoxetine was able to increase phospho-Ser21-GSK3α in the hippocampus, S21A-GSK3α-KI mice partially responded to fluoxetine in the forced swim test. Therefore, phosphorylation of GSK3β predominantly mediates the acute antidepressant-like effect of fluoxetine, which reinforces the importance of phosphorylation of GSK3β in the therapeutic action of fluoxetine (Figure 1).

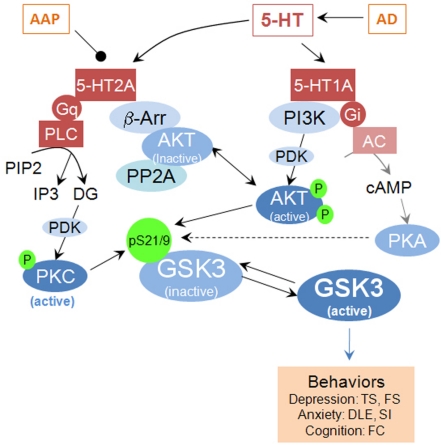

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of GSK3 as an intermediate modulator of 5-HT receptor-mediated signaling pathways and physiological functions. AAP, atypical antipsychotic; α, β, γ, G-protein subunits; AC, adenylyl cyclase; AD, antidepressant; β-arr, β-arrestin; DG, diacylglycerol; Gi/Gq, G-protein; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase-3; 5HT, serotonin; 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A, serotonin receptor subtypes; P, phosphorylated; PDK1, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; PP1/PP2A: protein phosphatase 2A; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C. TS, tail suspension; FS, forced swim; DLE, dark-light emergence; SI, social interaction; FC, fear conditioning.

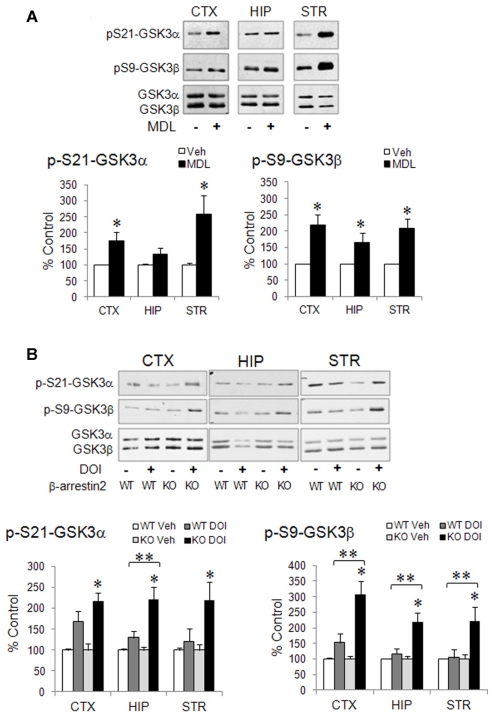

Since the antidepressant effect of fluoxetine in human only appears after chronic administration, to associate GSK3 regulation by fluoxetine to a therapeutic effect, it is important to determine if chronic fluoxetine treatment also regulates GSK3β. This has recently be reported by Okamoto et al. (2010) who found that chronic fluoxetine administration for 3 weeks significantly increased phospho-Ser9-GSK3β in mouse hippocampus. Although this is the only selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitor thus far shown to increase phospho-Ser9-GSK3β upon chronic treatment, a dual-acting antidepressant venlafaxine (blocks both 5-HT and norepinephrine transporters) has also been shown to increase phospho-Ser9-GSK3β after chronic administration (Okamoto et al., 2010). When investigating the effect of chronic treatment with imipramine, a TCA that inhibits reuptake of both 5-HT and norepinephrine on activation of Akt and down-stream transcription factor FoxO3a (Polter et al., 2009), we also noticed a significant increase in the level of phospho-Ser9-GSK3β in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and striatum of mouse brain after 4 weeks of intraperitoneal administration (Figure 2). It is not yet verified if the effect of venlafaxine and imipramine on GSK3β is a combined action via both 5-HT and norepinephrine, as regulation of brain GSK3β by selective adrenergic-enhancing drugs has not been studied.

Figure 2.

Regulation of phospho-Ser-GSK3 by chronic imipramine treatment in mouse brain. C57BL/6 mice were treated with imipramine (20 mg/kg/d, i.p.) for 28 days before brain dissection. Homogenates of the cerebral cortex (CTX), hippocampus (HIP), and striatum (STR) were immunoblotted for phospho-Ser21-GSK3α, phospho-Ser9-GSK3β, total GSK3α and total GSK3β, and data are quantified by densitometry. Protein levels in imipramine-treated samples are calculated as percentage control (saline treatment). Data are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 (n = 7–9 per group) when values are compared to saline treatment in Student’s t-test.

Regulation of GSK3 by 5-HT1A Receptors

Activation of 5-HT1A receptors regulates GSK3 by phosphorylation

With many physiological actions of brain 5-HT that are divergently mediated by 5-HT receptor subtypes, it is critically important to determine the receptor subtypes that transduce 5-HT signal to inhibition of GSK3. In mice treated with d-fenfluramine, the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY100635 was able to block over 60% of d-fenfluramine-induced increase in phospho-Ser9-GSK3β, suggesting that 5-HT1A receptors have a major role in mediating the GSK3-regulating effect of 5-HT. Indeed, when mice receive a single systemic administration of 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-hydroxy-N,N-dipropyl-2-aminotetralin (8-OH-DPAT), the level of phospho-Ser9-GSK3β, but not total GSK3β, is significantly increased in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and striatum (Li et al., 2004). 8-OH-DPAT is also able to increase the level of phospho-Ser21-GSK3α in the hippocampus, but the effect is less robust (Polter et al., 2011).

In the hippocampus, a brain area that is enriched in 5-HT1A receptors (Hoyer et al., 2002), GSK3β is ubiquitously expressed with high level of immunoreactivity in neuronal cell bodies and dendritic processes (Peineau et al., 2007; Perez-Costas et al., 2010). 8-OH-DPAT-induced increase in phospho-Ser9-GSK3β is particularly prominent in the dendrites and cell bodies of CA3, and is observable in the cell bodies and projections of dentate granule cells and the dendrites of CA1 (Polter et al., 2011). The quantified ratio of phospho-Ser9-GSK3β to nuclear marker in the subfields of the hippocampus reveals significant increases in the stratum pyramidale and the stratum radiatum/stratum lucidum of CA3 and in the hilus of the dentate gyrus. Therefore, the response of GSK3β to systemic administration of 8-OH-DPAT in the hippocampus is preferentially in the pyramidal glutamatergic neurons and their dendrites, suggesting that regulation of GSK3β by 5-HT1A receptors may have functional impact on the glutamatergic circuits of the hippocampus. GSK3β has been shown to be a mediator of glutamate receptor activity and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (Hooper et al., 2007; Peineau et al., 2007; Du et al., 2010), thus regulation of GSK3β by 5-HT1A receptors in the hippocampus may further link this 5-HT signaling mechanism to hippocampal regulation of learning and memory.

The role of GSK3 in 5-HT1A receptor-regulated behaviors and other physiological functions

Among 5-HT1A receptor-regulated behaviors, inhibition of contextual fear conditioning, a form of associative learning (Kim and Jung, 2006), is a hippocampus-dependent function (Stiedl et al., 2000; Tsetsenis et al., 2007; Ogren et al., 2008). To determine the role of GSK3β in 5-HT1A receptor-regulated fear conditioning, we tested the expression of contextual and cued fear responses in S9A-GSK3β-KI, S21A-GSK3α-KI, and littermate wild type mice. In wild type mice, 8-OH-DPAT (1 mg/kg, i.p.) injected 30 min prior to contextual test completely suppressed a standard fear conditioning training-induced contextual freezing (Polter et al., 2011). Compared to wild type mice, S9A-GSK3β-KI mice also exhibited increased freezing in contextual tests, but 8-OH-DPAT had no significant effect in reducing the context freezing. In contrast to S9A-GSK3β-KI mice, S21A-GSK3α-KI mice responded to 8-OH-DPAT in contextual freezing similarly as wild type mice. Thus, inhibition of GSK3β, but not GSK3α, via 5-HT1A receptors is a necessary intermediate process for 5-HT1A receptor-regulated inhibition of contextual fear learning. This function of GSK3β is selective to the contextual content since the response of cued fear learning to 8-OH-DPAT was similar in S9A-GSK3β-KI mice and wild type mice.

The functional significance of GSK3β in 5-HT1A receptor-mediated physiological functions is not limited to contextual fear learning. In cultured rat hippocampal neurons, 5-HT1A receptor activation by 8-OH-DPAT increases phospho-Ser9-GSK3β and stimulates mitochondrial movements in the axons, an effect mimicked by a GSK3 inhibitor (Chen et al., 2007). This finding suggests the importance of GSK3β in 5-HT1A receptor-mediated regulation of energy distribution in neurons. In Drosophila, over-expressing the mammalian 5-HT1A receptor ortholog d5-HT1B receptor increases the level of phosphorylated serine of SHAGGY (SGG), the Drosophila GSK3β (Yuan et al., 2005). This inhibitory regulation of SGG by d5-HT1B receptor prevents SGG from phosphorylating timeless (TIM) protein for light-induced degradation. Therefore, d5-HT1B receptor reduces behavioral phase shifts in Drosophila by increasing phospho-Ser-SGG. The role of GSK3 in other 5-HT1A receptor-mediated functions remains to be elucidated, but this could be an exciting area in therapeutic drug development, as GSK3 inhibitors, when applied appropriately, may rescue abnormal physiology and behaviors due to functional deficiency of 5-HT1A receptors in brain.

Signaling mechanisms mediating the effect of 5-HT1A receptors on GSK3

5-HT1A receptors activate Gi-coupled signal pathways. In a recent study, Talbot et al. (2010) found that mice expressing regulators of G protein signaling (RGS)-insensitive Giα2 have increased sensitivity to 8-OH-DPAT-induced activation, and exhibit elevated levels of cortical and hippocampal phospho-Ser9-GSK3β. This effect of RGS-insensitive active Giα2 was blocked by the 5-HT1A receptor antagonist WAY100635. This finding suggests that regulation of GSK3β by 5-HT1A receptors is mediated by a Gi-coupled signaling pathway (Figure 1). However, activation of Giα2 results in inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and inactivation of PKA. Although PKA is one of the several protein kinases that phosphorylate GSK3β on the serine-9 residue (Fang et al., 2000; Li et al., 2000), it is unlikely that this conventional Giα-coupled signaling pathway is responsible for direct phosphorylation of GSK3β. Alternatively, 5-HT1A receptor agonists have consistently shown to increase Akt phosphorylation in neuronal cells, including hippocampal derived HN2-5 cells (Adayev et al., 1999), primary hippocampal neurons (Cowen et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2007), and primary fetal rhombencephalic neurons (Druse et al., 2005). Regulation of Akt by 5-HT1A receptors is mediated by phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K; Cowen et al., 2005; Hsiung et al., 2005, 2008), and is sensitive to inhibition of Giα activity by pertussis toxin (Cowen et al., 2005). Furthermore, activation of Akt by 5-HT1A receptors can be inhibited by cAMP and restored after inactivation of PKA (Hsiung et al., 2008). Therefore, 5-HT1A receptor-induced activation of Akt likely follows 5-HT1A receptor-induced activation of the Giα–adenylyl cyclase–cAMP–PKA signaling pathway. Since Akt is another major protein kinase that regulates phospho-Ser9-GSK3β (Cross et al., 1995), Akt may mediate 5-HT1A receptor-induced GSK3β phosphorylation. Indeed, systemic treatment of mice with the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT significantly increased the active phospho-Thr308-Akt in the hippocampus, and intra-hippocampal infusion of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 blocked both phospho-Thr308-Akt and phospho-Ser9-GSK3β in response to 8-OH-DPAT (Polter et al., 2011).

Selectivity of GSK3 regulation by 5-HT1A receptors

As discussed above, activation of 5-HT1A receptors increases both phospho-Ser9-GSK3β and phospho-Ser21-GSK3α in the hippocampus, however, the magnitude of response in GSK3α is smaller than GSK3β (Polter et al., 2011). Additionally, regulation of GSK3α phosphorylation by 5-HT1A receptors has less impact in fear conditioning (Polter et al., 2011). These pilot studies suggest different roles of GSK3 isoforms in mediating the physiological and behavioral functions of 5-HT1A receptors. Additional studies are needed to differentiate the response of GSK3α and GSK3β to 5-HT1A receptor agonists in different brain regions, and to compare the impact of each GSK3 isoform in other 5-HT1A receptor-regulated behaviors, which may provide valuable information on the physiological and behavioral impacts of the two GSK3 isoforms in 5-HT neurotransmission.

A caveat of studying 5-HT1A receptor-regulated signaling in brain is that the differential functions of 5-HT1A autoreceptors and heteroreceptors in different brain regions have divergent functions. Thus, systemic treatment of animals with 5-HT1A receptor agonists can activate 5-HT1A autoreceptors to reduce firing of raphe 5-HT neurons projected to other brain regions, but simultaneously activate 5-HT1A heteroreceptors in those brain regions, such as the hippocampus. Therefore, the effect seen after global activation of 5-HT1A receptors may involve indirect response of GSK3 to activation or inhibition of other neurotransmitters. Therefore, additional studies of GSK3 regulation by systemically and regionally applied 5-HT1A receptor agonists in specific neuron populations in combination with studies in isolated primary neuron cultures will further elucidate the sophisticated mechanisms underlying the GSK3-regulating effect of 5-HT1A receptors. Nevertheless, the effect of global activation of 5-HT1A receptors should be appreciated since systemic drug treatment is likely more relevant to therapeutic implications.

Regulation of GSK3 by 5-HT2A Receptors

The paradoxical effects of 5-HT2A receptor agonists and antagonists on GSK3

Although 5-HT1A receptors have a prominent regulatory effect on GSK3, more than one 5-HT receptor subtype should be activated upon elevated brain 5-HT. Among them, 5-HT2A receptors have been found to regulate GSK3 with rather sophisticated and yet unidentified mechanisms. We previously reported that activation of 5-HT2A receptors by systemic administration of 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-propan-2-amine (DOI) for 1 h (a time point that maximally increases phospho-Ser9-GSK3β by d-fenfluramine, fluoxetine, and 8-OH-DPAT), had little effect on phospho-Ser9-GSK3β in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, or striatum (Li et al., 2004). However, Abbas et al. (2009) later reported that a brief 15-min DOI treatment caused an increase in phospho-Ser9-GSK3β in the mouse brain, although this report did not specify the brain region in which this effect was seen. If the time length of treatment is the major difference of the discrepant findings, one possibility is that 1 h treatment might have caused desensitization of 5-HT2A receptors. Therefore a thorough kinetic study of 5-HT2A receptor agonists may further clarify their effect on GSK3, especially the effects in different brain regions.

Since activation of 5-HT2A receptors by the hallucinogen DOI is somewhat different from 5-HT-induced activation of 5-HT2A receptors (Schmid et al., 2008), the exact action of 5-HT2A receptor activation on GSK3 phosphorylation should be further elucidated using endogenous 5-HT2A receptor agonists and selective 5-HT2A receptor antagonists. However, this has been difficult to study with 5-HT2A receptors, because it is already known that endogenous 5-HT increases phospho-Ser-GSK3 by activating other 5-HT receptors, particularly 5-HT1A receptors (Li et al., 2004); whereas selective blocking 5-HT2A receptors with their antagonists, one of the commonly used manipulations to determine a receptor-selective effect, paradoxically elicit robust increase in the level of phospho-Ser-GSK3 in mouse brain. This phenomenon was first observed with the non-selective 5-HT2 receptor antagonist LY53857 (Li et al., 2004). Systemic LY53857 treatment not only caused a prolonged elevation of phospho-Ser9-GSK3β, but it also potentiated the GSK3β-regulating effect of d-fenfluramine and 8-OH-DPAT. This effect has also been observed using the 5-HT2A receptor-selective antagonist MDL11939, which elevates both phospho-Ser21-GSK3α and phospho-Ser9-GSK3β in mouse brain, with the effect more prominent in the cerebral cortex and striatum and less in the hippocampus (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Regulation of phospho-Ser-GSK3 by 5-HT2A receptor ligands in mouse brain. (A) Wild type mice were treated with saline (Veh) or the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist MDL11939 (MDL, 4 mg/kg, i.p., 1 h). Immunoblots of phospho-Ser21-GSK3α, phospho-Ser9-GSK3β, total GSK3α, and total GSK3β in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and striatum are quantified by densitometry. Mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 when values are compared to saline treatment in Student’s t-test, n = 4–13. (B) Wild type (WT) and β-arrestin2-knockout (KO) mice were treated with saline (Veh) or DOI (20 mg/kg, i.p.) for 1 h. Immunoblots of phospho-Ser21-GSK3α, phospho-Ser9-GSK3β, total GSK3α, and total GSK3β in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and striatum are quantified by densitometry. Mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 between saline and DOI treatment within the same genotype, Student’s t-test; **p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak comparison, n = 10–12.

The effect of atypical antipsychotics on GSK3

Despite the paradoxical nature of 5-HT2A receptors in regulating GSK3, the effect of 5-HT2A receptor antagonists may have clinical significance. Several independent studies have found that antipsychotic drugs, including both conventional and atypical antipsychotics, regulate GSK3 in animal brain. The conventional antipsychotic haloperidol was reported to either alter the phosphorylation state or increase the protein level of GSK3 (Alimohamad et al., 2005; Kozlovsky et al., 2006; Roh et al., 2007). A group of atypical antipsychotics, including risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone, were consistently found to increase phospho-Ser-GSK3 in mouse brain (Alimohamad et al., 2005; Li et al., 2007; Roh et al., 2007). Although the dopamine D2 receptor-blocking property of these agents may be involved in their GSK3-regulating effect (Beaulieu et al., 2009), one of the major pharmacological difference between conventional antipsychotics and atypical antipsychotics is that the latter group has a dual antagonistic action on both 5-HT2 receptors and dopamine D2 receptors (Schotte et al., 1995). In our study, a low dose haloperidol that binds to D2 receptors but not 5-HT2A receptors had no effect on mouse brain GSK3 (Li et al., 2007). In contrast, systemic administered risperidone increases brain phospho-Ser9-GSK3β at a dose as low as 0.1 mg/kg (Li et al., 2007). As the average dose of risperidone used to attain a 50% in vivo blockade of D2 receptors in rats is about 0.3 mg/kg (Kapur et al., 2003), and the binding affinity of risperidone to 5-HT2A receptors is at least 3 times higher than to D2 receptors (Weiner et al., 2001), it is likely that the increase of phospho-Ser9-GSK3β by the low dose risperidone involves blocking 5-HT2A receptors. It remains to be determined if putative 5-HT2A receptor antagonists have similar clinical implications as atypical antipsychotics, and if such effects are dependent on regulation of GSK3.

Clinically, atypical antipsychotics have indications in both psychotic disorders and mood disorders (Derry and Moore, 2007; Philip et al., 2008). Some atypical antipsychotics, either as monotherapy or augmentation, have shown efficacy in ameliorating symptoms of depression (Tohen et al., 2003; Calabrese et al., 2005; Berman et al., 2007; Marcus et al., 2008; Bauer et al., 2009). Interestingly, a combination treatment with risperidone and fluoxetine enhance the effect of either agent alone on phosphorylation of GSK3β in the rodent brain (Li et al., 2007). This effect agrees with the finding that the 5-HT2 receptor antagonist LY53857 potentiated the effect of d-fenfluramine and 8-OH-DPAT on GSK3 phosphorylation. However, the role of GSK3 in this clinically relevant combination effect between antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics remains to be determined.

Signaling mechanisms involved in regulation of GSK3 by 5-HT2A receptors

Few studies have investigated the signaling mechanisms that mediate the effects of either 5-HT2A receptor agonists or antagonists on GSK3 phosphorylation. Classically, the 5-HT2A receptors couple to Gq protein that activates PLC and its down-stream PKC (Carr et al., 2002; Figure 1). PKC was reported to mediate DOI-induced Erk phosphorylation in the brain (Schmid et al., 2008). Since PKC is one of the protein kinases that regulate GSK3 phosphorylation (Goode et al., 1992), it would be straightforward if the PLC/PKC signaling mechanism is found to mediate 5-HT2A receptor-regulated GSK3. However, this mechanism has not been reported, especially since the kinetic correlation between 5-HT2A receptor activation and phosphorylation of GSK3 has not been characterized. In a study of dopamine D2 receptor-regulated signaling (Beaulieu et al., 2004), the intracellular scaffolding protein β-arrestins were found to negatively affect GSK3 phosphorylation in mouse brain, wherein activation of dopamine D2 receptors reduces phospho-Ser9-GSK3 due to inactivation of Akt by protein phosphatase-2 (PP2A) in a β-arrestin2-driven protein complex (Beaulieu et al., 2005). D2 receptor antagonists block this effect of dopamine and increase phospho-Ser-GSK3 by disrupting the effect of β-arrestins. 5-HT2A receptors also interact with β-arrestins in a cell type- and ligand-selective manner (Gelber et al., 1999; Allen et al., 2008; Schmid et al., 2008; Schmid and Bohn, 2010), but the role of β-arrestins in 5-HT2A receptor-regulated signal pathways is less understood. It should be noted that in a previous study by Schmid et al. (2008), DOI-induced head twitch, receptor internalization, and Erk phosphorylation are not dependent on the presence or absence of β-arrestins. However, we have recently found that DOI treatment for 1 h induced a significant over twofold increase in phospho-Ser21-GSK3α and phospho-Ser9-GSK3β in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and striatum in β-arrestin2-knockout mice, an effect that is not seen in wild type mice (Figure 3B). This observation suggests that β-arrestin2 may influence how 5-HT2A receptors regulate GSK3. Future studies investigating signal transduction mechanisms mediating the effect of 5-HT2A receptors on GSK3 should include not only PLC/PKC signaling, but also β-arrestin-mediated signaling. Additionally, since 5-HT2A receptors are involved in modulating dopamine neurotransmission (Alex and Pehek, 2007; Di Giovanni et al., 2008; Esposito et al., 2008), a potential indirect effect of 5-HT2A receptors on D2 receptor-regulated GSK3 should also be considered.

GSK3 Selectively Regulates 5-HT1B Receptor-Mediated Signal Transduction and Function

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 phosphorylates many protein substrates that distribute in both neural and peripheral tissues (Woodgett, 2001; Jope and Johnson, 2004). As a result, in vivo inhibition of GSK3 can have a variety of physiological effects. Thus, identifying GSK3 substrates that have specific functions in brain circuits could be critical in developing GSK3-targeting treatment for therapeutics. With each clearly identified substrate, substrate-targeting inhibition of brain GSK3 activity may lead to selective modulation of physiological function of the brain. Most 5-HT receptor subtypes, except 5-HT3 receptors, are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) that represent the largest group of drug targets. Besides activation by receptor ligands, the activity of GPCRs can be modulated by posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation by protein kinases (Tobin, 2008), or interaction with intracellular proteins (Ritter and Hall, 2009; Bockaert et al., 2010). However, little evidence has shown GPCR regulation by GSK3.

Direct interaction between GSK3β and 5-HT1B receptors

In an effort to identify GSK3 substrates within the 5-HT neurotransmission system, we searched GSK3 consensus phosphorylation sequence for primed substrates – pre-phosphorylated by a serine/threonine kinase to allow access of GSK3 to the serine/threonine located four amino acids N-terminal of the primed site (Doble and Woodgett, 2003). Somewhat surprisingly, both human and mouse 5-HT1B receptors were found to contain eight GSK3 consensus phosphorylation sites spreading within intracellular loops 1, 2, and 3 of the receptor. In contrast, the highly homologous 5-HT1A receptors have no GSK3 consensus sites in intracellular loops 1 and 2, and the two sites in intracellular loop-3 of human 5-HT1A receptors are not homologous with mouse 5-HT1A receptors. In cultured heterologous cells expressing 5-HT1B or 5-HT1A receptors, GSK3β was found to directly associate with 5-HT1B receptors (Chen et al., 2009), which was detected using the bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assay that measures the proximity of two proteins within a distance of 1–10 nm (Angers et al., 2000), and confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation of 5-HT1B receptors and GSK3β. Intriguingly, this interaction of GSK3β is selective to 5-HT1B receptors, as GSK3β does not interact with 5-HT1A receptors (Chen et al., 2009). Mutation of every potential GSK3 consensus phosphorylation site of 5-HT1B receptors by replacing the serine with alanine further shows that GSK3β associates with 5-HT1B receptors at the [pS(154)AKRpT(158)] sequence located in the i2-loop of 5-HT1B receptors (Chen et al., 2009).

GSK3β differentially influences 5-HT1B receptor activity and associated signalings

Both 5-HT1B and 5-HT1A receptors couple to Gi-protein, activation of which causes inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and reduction of cAMP. Disrupting the interaction between 5-HT1B receptors and GSK3β by mutating the GSK3β-interactive Ser-154 residue of the receptor (S154A–5-HT1B receptor) effectively abolishes 5-HT-induced conformational change between 5-HT1B receptors and Giα2 (Chen et al., 2011). In accordance with altered activity of Giα2, GSK3β-insensitive S154A–5-HT1B receptor does not respond to 5-HT in assay of 5-HT-induced inhibition of cAMP (Chen et al., 2009). These data highly suggest that GSK3β has a functional impact on 5-HT1B receptor-mediated signaling. Indeed, several small molecule GSK3 inhibitors and the clinically used lithium are able to disrupt 5-HT-induced conformational change between 5-HT1B receptors and Giα2 and inhibition of cAMP. This is a highly selective function of the GSK3β isoform, as it only occurs in cells with GSK3β-knockdown or over-expressing inactive GSK3β, but GSK3α-knockdown does not affect 5-HT1B receptor-associated Giα–cAMP signaling (Chen et al., 2009, 2011). This is another example showing that despite GSK3α and GSK3β are highly homologous and are regulated via similar upstream mechanisms, the two isoforms of GSK3 have different substrates and mediate different physiological functions (Wang et al., 1994; Liang and Chuang, 2006). In agreement with a selective interaction between GSK3β and 5-HT1B receptors, GSK3 inhibitors and molecular manipulation of intracellular GSK3β do not alter 5-HT-induced 5-HT1A receptor-Giα2 interaction or 5-HT1A receptor-mediated inhibition of cAMP.

Giα-mediated cAMP production is not the only GSK3-dependent signaling pathway of 5-HT1B receptors as activation of Akt by 5-HT or the selective 5-HT1B receptor agonist anpirtoline is also significantly diminished in the mutant S154A–5-HT1B receptor-expressing cells (Chen et al., 2011). The mechanisms of regulating Akt by 5-HT1B receptors are not fully understood, but since both α- and βγ-subunits of G-proteins may be linked to GPCR-induced activation of Akt (DeWire et al., 2007; New et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2009), the effect of GSK3β on 5-HT1B receptor-induced Akt activation could be a consequence of the prominent effect of GSK3β on 5-HT1B receptor-associated Gi-protein. In addition, since Akt is one of the upstream GSK3-regulating protein kinases that inactivates GSK3 (Cross et al., 1995), the GSK3-dependent activation of Akt by 5-HT1B receptors could function as a feedback regulation to prevent prolonged effect of GSK3β on 5-HT1B receptors, but this postulation remains to be examined.

As a GPCR, 5-HT1B receptors are expected to interact with β-arrestins that have been recognized to interact with many GPCRs and play important roles in GPCR internalization and alternative signaling (Lefkowitz and Shenoy, 2005). Indeed, we found that β-arrestin2 can be recruited to 5-HT1B receptors in response to 5-HT. However, in contrast to the prominent effect of GSK3β on 5-HT1B receptor-coupling to Giα2, removing, or inhibiting GSK3β did not affect β-arrestin2 recruitment to 5-HT1B receptors (Chen et al., 2011). As a chaperone protein, recruitment of β-arrestins to GPCRs initiates receptor internalization and desensitization (Bohn et al., 1999, 2000). 5-HT was able to internalize both wild type and S154A–5-HT1B receptors in 5-HT1B receptor-expressing cells (Chen et al., 2009). If this internalization event is directed by β-arrestin2, it is in agreement with our finding that β-arrestin2 recruitment to 5-HT1B receptors is independent of GSK3β. However, the time course of 5-HT1B receptor internalization is drastically different between wild type and the mutant S154A–5-HT1B receptors, wherein wild type receptors rapidly reappear on the cell membranes within 60 min of 5-HT treatment, while mutant GSK3β-insensitive receptors continue to be absent from the cell surface 2 h after 5-HT treatment. This suggests a potentially important function of GSK3β in an unidentified mechanism that is crucial for 5-HT1B receptor synthesis and membrane recycling.

Interestingly, the effect of GSK3β on 5-HT1B receptors appears to facilitate activity and functional recovery, which is opposite from other GPCR-regulating protein kinases (GRKs) that typically facilitate desensitization and termination of GPCR activity (Gainetdinov et al., 2004). The underlying importance of GSK3β on 5-HT1B receptor-mediated Gi signaling and β-arrestin recruitment is that GSK3β does not function as a general 5-HT1B receptor activator, instead, GSK3β selectively modulates signaling-specific actions of 5-HT1B receptors. This effect of GSK3β could be attractive when developing GSK3-targeting therapeutic agents, as inhibition of GSK3β would not make inert 5-HT1B receptors, but to selectively shift 5-HT1B receptor-mediated physiological and behavioral functions toward a Gi signaling-independent direction. This postulation is an important area of future research especially when β-arrestin-associated 5-HT1B receptor signaling pathways are identified.

Effect of GSK3 inhibitors on the physiological functions of 5-HT1B receptors

Noticeably, several earlier studies showed that lithium selectively inhibits 5-HT binding to 5-HT1B receptors, reduces 5-HT1B receptor-induced GTPγs binding, and abolishes 5-HT1B receptor-reduced adenylyl cyclase activity (Massot et al., 1999). Similar results have been observed in human platelets from both healthy and depressed subjects where lithium dose-dependently reverses the inhibitory effect of a 5-HT1BR agonist on adenylyl cyclase (Januel et al., 2002). In animal behavior studies, lithium selectively regulates the behavioral effect of 5-HT1B receptor agonists, but not the effect of 5-HT1A receptor agonists (Redrobe and Bourin, 1999). With lithium being a selective GSK3 inhibitor (Klein and Melton, 1996), it is highly likely that the selective effect of lithium on 5-HT1B receptor function is the result of its inhibition of GSK3. Since lithium is a therapeutic drug that has been found to inhibit GSK3 in vivo, perhaps by both its direct and indirect actions on GSK3 (Klein and Melton, 1996; Chalecka-Franaszek and Chuang, 1999; De Sarno et al., 2002), disrupting the interaction between 5-HT1B receptors and GSK3β may have significant impact in the physiological functions of 5-HT1B receptors and relevant therapeutic effects in neuropsychiatric diseases.

The above postulation has been tested now in mouse brain tissues using small GSK3 inhibitors. When mouse cerebral cortical slices are pre-treated with the GSK3 inhibitors 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime (BIO) or kenpaullone, both inhibitors concentration-dependently abolish the inhibitory effect of 5-HT1B receptor agonist anpirtoline on forskolin-stimulated cAMP, whereas neither affects the effect of 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT on cAMP (Chen et al., 2009). This finding in brain tissues is consistent with findings in cultured cells, where ablation or inhibition of GSK3β selectively abolishes 5-HT1B receptor-mediated Giα–cAMP signaling. Furthermore, pre-treatment of cortical slices with the GSK3 inhibitors AR-A014418 (Bhat et al., 2003) and BIP-135 (Gaisina et al., 2009) completely abolish the inhibitory effect of anpirtoline on potassium-evoked 3H-5-HT release (Chen et al., 2011). Since negatively regulating 5-HT release is a characteristic function of 5-HT1B autoreceptors in the axon terminals of 5-HT neurons (Trillat et al., 1997; Riad et al., 2000; Sari, 2004), this finding suggests that active GSK3 plays a role to rapidly resets the surge of 5-HT to baseline, which may result in termination of a physiological or behavioral action of 5-HT. In reverse, inhibition of GSK3 may be important in maintaining 5-HT at a sufficient level that allows 5-HT to deliver sustained physiological action. The signaling pathways mediating 5-HT1B autoreceptor-induced inhibition of 5-HT release have never been confirmed. In a study conducted in 5-HT1B receptor-expressing cardiac ventricle myocytes, inhibition of 5-HT release by 5-HT1B receptors was found to be a pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi-mediated effect, where the effect was not mediated by cAMP, but by an inwardly rectifying potassium channel (Ghavami et al., 1997). However, pertussis toxin-dependent 5-HT release by 5-HT1B receptors in the brain has not been confirmed. It should therefore be noted that although GSK3 inhibitors abolish the effect of 5-HT1B receptors on Gi-associated signalings and 5-HT release, the latter is not necessarily due to the impaired 5-HT1B receptor-Giα coupling.

Effect of GSK3 inhibitors on 5-HT1B receptor-regulated behaviors

If GSK3β differentially affects 5-HT1B receptor-mediated signal transduction and brain physiological function, it would be expected that GSK3 inhibitors may also differentially affect 5-HT1B receptor-regulated behaviors. Indeed, intra-cerebroventricular infusion of GSK3 inhibitor AR-A014418 or BIP-135 prior to systemic administration of anpirtoline significantly facilitates the anti-immobility effect of the 5-HT1B receptor agonist in the tail suspension test (Chen et al., 2011). In this behavioral test, low doses of GSK3 inhibitors and anpirtoline are used so that GSK3 inhibitors alone has no effect and anpirtoline alone only mildly reduces the immobility, which highlights the combination effect of GSK3 inhibition and 5-HT1B receptor activation. Finding of this study suggests that GSK3 inhibitors facilitate the anti-immobility effect of 5-HT1B heteroreceptors by abolishing 5-HT1B autoreceptor-mediated inhibition of serotonin release. Interestingly, the anpirtoline-induced increase in horizontal locomotor activity was not altered by GSK3 inhibitors, but is largely diminished in β-arrestin2-knockout mice (Chen et al., 2011), which is in agreement with the in vitro findings showing that association of β-arrestin2 with 5-HT1B receptors does not depend on GSK3β. Therefore, these initial behavior data further suggest that GSK3 has differential effects in modulating 5-HT1B receptor functions in brain.

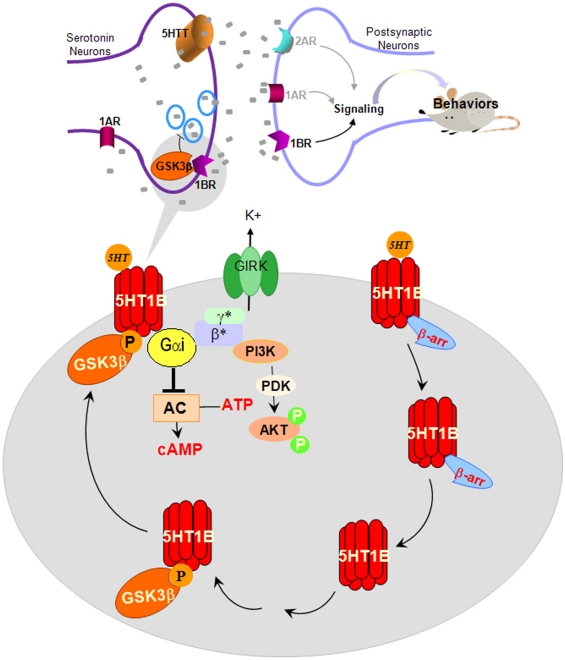

Taken together, molecular and in vivo studies support a prominent effect of GSK3β to selectively regulate 5-HT1B receptor function (Figure 4). The effect of GSK3β is elicited by directly interacting with 5-HT1B receptors at the intracellular loop-2. This interaction functions to facilitate 5-HT1B receptor-regulated Giα-mediated signaling. In the absence of GSK3β, 5-HT1B receptors are dissociated from the conventional Giα-mediated signaling, but still able to respond to agonist-induced recruitment of β-arrestin2 and receptor internalization. Regulation of 5-HT1B receptors by GSK3β has functional significance since it impacts 5-HT1B receptor-dependent 5-HT release. Although this and other physiological functions of the highly selective modulation of 5-HT1B receptors by GSK3β remain to be investigated in further detail, initial evidence supports a significant behavioral impact of this GSK3 action that may be important for therapeutic development. Several important questions remain to be addressed before the importance of this unique effect of GSK3β is completely elucidated. Particularly important is to understand if the effect of GSK3β is selective to 5-HT1B autoreceptors only or both auto- and hetero-receptors, which 5-HT1B receptor-regulated signaling mechanisms in the brain are affected by GSK3β, and if the GSK3β-dependent signaling pathways correlate with the effect of GSK3β on the physiological and behavioral functions of brain 5-HT1B receptors.

Figure 4.

Proposed effects of GSK3β in regulating 5-HT1B receptor-coupled signal transduction, 5-HT1B receptor-regulated 5-HT release, and 5-HT1B receptor-regulated behaviors. α, β, γ, G-protein subunits; AC, adenylyl cyclase; β-arr, β-arrestin; Gi, G-protein; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase-3; 5HT, serotonin; 1AR, 1BR, 2AR, serotonin receptor subtypes; P, phosphorylated; PDK, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase.

Summary

Cumulative evidence from in vitro measurements, pharmacological studies, and animal behavioral tests strongly support GSK3 as an integrative mediator of 5-HT neurotransmission. First, GSK3 is an early intracellular responder to a surge of brain 5-HT, which results in GSK3 phosphorylation at an N-terminal serine and inactivation of its constitutive activity. Phosphorylation of GSK3 by increasing brain 5-HT may be therapeutically important as the behavioral effect of fluoxetine is mediated by GSK3 phosphorylation. Second, GSK3 is a down-stream target of 5-HT1A receptor signaling, and enhancing GSK3 phosphorylation by 5-HT1A receptors in the hippocampus is associated with its inhibitory effect on contextual fear learning. Third, 5-HT2A receptors elicit sophisticated regulatory effect on GSK3, as both agonist and antagonist of 5-HT2A receptors may inactivate it, but the effects likely depend on the receptor activation state and the presence of other receptor interactive proteins. Regulation of GSK3 by 5-HT2A receptors may have therapeutic implication as evidenced by the prominent inhibitory effect of atypical antipsychotics on GSK3, presumably related to the 5-HT2A receptor antagonistic effect of these drugs. Finally, GSK3β interacts with and modulates 5-HT1B receptor activity in a receptor subtype- and signaling pathway-selective manner. Although the physiological impact of this action in intact brain remains to be elucidated, it is predicted that this action of GSK3β is to rapidly reset the level of 5-HT in certain brain areas to ameliorate prolonged effect of 5-HT, whereas the therapeutic implication of this unique action of GSK3 remains to be further studied.

The prominent effect of GSK3 on serotonin neurotransmission may partially explain the many findings of behavioral actions of GSK3 as well as it being a converging target of mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and antipsychotics (Li and Jope, 2010). Integrating 5-HT neurotransmission by GSK3 may be particularly indicative in the pathophysiological roles of GSK3 in mood, anxiety, and cognitive disorders that involve dysregulation of 5-HT neurotransmission, and in the therapeutics targeting GSK3 for the treatment of these diseases.

However, our current knowledge on this potentially important function of GSK3 is limited. GSK3 has only been found to associate with 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and 5-HT2A receptors. Evidence showing GSK3 as a down-stream target or a modulator of other 5-HT receptor subtypes is still lacking. As discussed in this review, the two isoforms of GSK3 appear to have common and unique relations to different 5-HT receptors, but it is not yet clear if the divergent relationship is receptor subtype- or brain region-specific. Additional investigations are also necessary to fully understand how altered activity of GSK3 affects 5-HT-regulated behaviors, and to determine the mechanisms of how each behavior is affected by altered GSK3 activity. Since GSK3 is a protein kinase, an important task is to identify specific protein substrates that mediate the divergent physiological and behavioral effects of GSK3 within and beyond 5-HT neurotransmission. Human studies are needed to determine if clinical findings support the ample preclinical evidence suggesting a role of GSK3 in 5-HT dysregulation and related brain disorders. Finally, all the ongoing and future research tasks should converge to developing GSK3 modulators that are able to substitute, facilitate, or supplement therapeutic drugs that are known to modulate 5-HT neurotransmission.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author of this article is supported by NIH grant MH86622.

References

- Abbas A. I., Yadav P. N., Yao W. D., Arbuckle M. I., Grant S. G., Caron M. G., Roth B. L. (2009). PSD-95 is essential for hallucinogen and atypical antipsychotic drug actions at serotonin receptors. J. Neurosci. 29, 7124–7136 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1090-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adayev T., El-Sherif Y., Barua M., Penington N. J., Banerjee P. (1999). Agonist stimulation of the serotonin1A receptor causes suppression of anoxia-induced apoptosis via mitogen-activated protein kinase in neuronal HN2-5 cells. J. Neurochem. 72, 1489–1496 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721489.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimova E., Lanzenberger R., Kasper S. (2009). The serotonin-1A receptor in anxiety disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 627–635 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert P. R., Lemonde S. (2004). 5-HT1A receptors, gene repression, and depression: guilt by association. Neuroscientist 10, 575–593 10.1177/1073858404267382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alex K. D., Pehek E. A. (2007). Pharmacologic mechanisms of serotonergic regulation of dopamine neurotransmission. Pharmacol. Ther. 113, 296–320 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alimohamad H., Rajakumar N., Seah Y. H., Rushlow W. (2005). Antipsychotics alter the protein expression levels of beta-catenin and GSK-3 in the rat medial prefrontal cortex and striatum. Biol. Psychiatry 57, 533–542 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J. A., Yadav P. N., Roth B. L. (2008). Insights into the regulation of 5-HT2A serotonin receptors by scaffolding proteins and kinases. Neuropharmacology 55, 961–968 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angers S., Salahpour A., Joly E., Hilairet S., Chelsky D., Dennis M., Bouvier M. (2000). Detection of beta 2-adrenergic receptor dimerization in living cells using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3684–3689 10.1073/pnas.060590697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banasr M., Hery M., Printemps R., Daszuta A. (2004). Serotonin-induced increases in adult cell proliferation and neurogenesis are mediated through different and common 5-HT receptor subtypes in the dentate gyrus and the subventricular zone. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 450–460 10.1038/sj.npp.1300320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M., Pretorius H. W., Constant E. L., Earley W. R., Szamosi J., Brecher M. (2009). Extended-release quetiapine as adjunct to an antidepressant in patients with major depressive disorder: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70, 540–549 10.4088/JCP.08m04629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2009). Akt/GSK3 signaling in the action of psychotropic drugs. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 49, 327–347 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Marion S., Rodriguiz R. M., Medvedev I. O., Sotnikova T. D., Ghisi V., Wetsel W. C., Lefkowitz R. J., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2008a). A beta-arrestin 2 signaling complex mediates lithium action on behavior. Cell 132, 125–136 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Zhang X., Rodriguiz R. M., Sotnikova T. D., Cools M. J., Wetsel W. C., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2008b). Role of GSK3 beta in behavioral abnormalities induced by serotonin deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1333–1338 10.1073/pnas.0803026105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Sotnikova T. D., Marion S., Lefkowitz R. J., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2005). An Akt/beta-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell 122, 261–273 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. M., Sotnikova T. D., Yao W. D., Kockeritz L., Woodgett J. R., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2004). Lithium antagonizes dopamine-dependent behaviors mediated by an AKT/glycogen synthase kinase 3 signaling cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 5099–5104 10.1073/pnas.0307921101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman R. M., Marcus R. N., Swanink R., McQuade R. D., Carson W. H., Corey-Lisle P. K., Khan A. (2007). The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68, 843–853 10.4088/JCP.v68n0604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat R., Xue Y., Berg S., Hellberg S., Ormo M., Nilsson Y., Radesäter A. C., Jerning E., Markgren P. O., Borgegård T., Nylöf M., Giménez-Cassina A., Hernández F., Lucas J. J., Díaz-Nido J., Avila J. (2003). Structural insights and biological effects of glycogen synthase kinase 3-specific inhibitor AR-A014418. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45937–45945 10.1074/jbc.M306268200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi M., Moser C., Lazzarini C., Vecchiato E., Crespi F. (2002). Forced swimming test and fluoxetine treatment: in vivo evidence that peripheral 5-HT in rat platelet-rich plasma mirrors cerebral extracellular 5-HT levels, whilst 5-HT in isolated platelets mirrors neuronal 5-HT changes. Exp. Brain Res. 143, 191–197 10.1007/s00221-001-0979-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blier P., Ward N. M. (2003). Is there a role for 5-HT1A agonists in the treatment of depression? Biol. Psychiatry 53, 193–203 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01643-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockaert J., Claeysen S., Becamel C., Dumuis A., Marin P. (2006). Neuronal 5-HT metabotropic receptors: fine-tuning of their structure, signaling, and roles in synaptic modulation. Cell Tissue Res. 326, 553–572 10.1007/s00441-006-0286-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockaert J., Perroy J., Becamel C., Marin P., Fagni L. (2010). GPCR interacting proteins (GIPs) in the nervous system: roles in physiology and pathologies. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 50, 89–109 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn L. M., Gainetdinov R. R., Lin F. T., Lefkowitz R. J., Caron M. G. (2000). Mu-opioid receptor desensitization by beta-arrestin-2 determines morphine tolerance but not dependence. Nature 408, 720–723 10.1038/35047086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn L. M., Lefkowitz R. J., Gainetdinov R. R., Peppel K., Caron M. G., Lin F. T. (1999). Enhanced morphine analgesia in mice lacking beta-arrestin 2. Science 286, 2495–2498 10.1126/science.286.5449.2495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhelal R., Smounya L., Bockaert J. (1988). 5-HT1B receptors are negatively coupled with adenylate cyclase in rat substantia nigra. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 151, 189–196 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90799-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese J. R., Keck P. E., Jr., Macfadden W., Minkwitz M., Ketter T. A., Weisler R. H., Cutler A. J., McCoy R., Wilson E., Mullen J. (2005). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 1351–1360 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. B., Cooper D. C., Ulrich S. L., Spruston N., Surmeier D. J. (2002). Serotonin receptor activation inhibits sodium current and dendritic excitability in prefrontal cortex via a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. J. Neurosci. 22, 6846–6855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalecka-Franaszek E., Chuang D. M. (1999). Lithium activates the serine/threonine kinase Akt-1 and suppresses glutamate-induced inhibition of Akt-1 activity in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 8745–8750 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Salinas G. D., Li X. (2009). Regulation of serotonin 1B receptor by glycogen synthase kinase-3. Mol. Pharmacol. 76, 1150–1161 10.1124/mol.109.056994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Zhou W., Chen P., Gaisina I., Yang S., Li X. (2011). Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta is a functional modulator of serotonin 1b receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 79, 974–986 10.1124/mol.111.071092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Owens G. C., Crossin K. L., Edelman D. B. (2007). Serotonin stimulates mitochondrial transport in hippocampal neurons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 36, 472–483 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenu F., David D. J., Leroux-Nicollet I., Le Maitre E., Gardier A. M., Bourin M. (2008). Serotonin1B heteroreceptor activation induces an antidepressant-like effect in mice with an alteration of the serotonergic system. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 33, 541–550 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn P. J., Sanders-Bush E. (1984). Selective 5HT-2 antagonists inhibit serotonin stimulated phosphatidylinositol metabolism in cerebral cortex. Neuropharmacology 23, 993–996 10.1016/0028-3908(84)90017-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornea-Hebert V., Riad M., Wu C., Singh S. K., Descarries L. (1999). Cellular and subcellular distribution of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in the central nervous system of adult rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 409, 187–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen D. S., Johnson-Farley N. N., Travkina T. (2005). 5-HT receptors couple to activation of Akt, but not extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK), in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Neurochem. 93, 910–917 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03107.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen D. S., Sowers R. S., Manning D. R. (1996). Activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK2) by the 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptor is sensitive not only to inhibitors of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, but to an inhibitor of phosphatidylcholine hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 22297–22300 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross D. A., Alessi D. R., Cohen P., Andjelkovich M., Hemmings B. A. (1995). Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 378, 785–789 10.1038/378785a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson L. A., Hughes Z. A., Starr K. R., Storey J. D., Bettelini L., Bacchi F., Arban R., Poffe A., Melotto S., Hagan J. J., Price G. W. (2006). Characterisation of the selective 5-HT1B receptor antagonist SB-616234-A (1-[6-(cis-3,5-dimethylpiperazin-1-yl)-2,3-dihydro-5-methoxyindol-1-yl]-1- [2′-methyl-4′-(5-methyl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)biphenyl-4-yl]methanone hydrochloride): in vivo neurochemical and behavioural evidence of anxiolytic/antidepressant activity. Neuropharmacology 50, 975–983 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarno P., Li X., Jope R. S. (2002). Regulation of Akt and glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta phosphorylation by sodium valproate and lithium. Neuropharmacology 43, 1158–1164 10.1016/S0028-3908(02)00215-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vivo M., Maayani S. (1986). Characterization of the 5-hydroxytryptamine1a receptor-mediated inhibition of forskolin-stimulated adenylate cyclase activity in guinea pig and rat hippocampal membranes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 238, 248–253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derry S., Moore R. A. (2007). Atypical antipsychotics in bipolar disorder: systematic review of randomised trials. BMC Psychiatry 7, 40. 10.1186/1471-244X-7-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWire S. M., Ahn S., Lefkowitz R. J., Shenoy S. K. (2007). Beta-arrestins and cell signaling. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 69, 483–510 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni G., Di Matteo V., Pierucci M., Esposito E. (2008). Serotonin-dopamine interaction: electrophysiological evidence. Prog. Brain Res. 172, 45–71 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00903-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doble B. W., Woodgett J. R. (2003). GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J. Cell. Sci. 116, 1175–1186 10.1242/jcs.00384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druse M., Tajuddin N. F., Gillespie R. A., Le P. (2005). Signaling pathways involved with serotonin1A agonist-mediated neuroprotection against ethanol-induced apoptosis of fetal rhombencephalic neurons. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 159, 18–28 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Wei Y., Liu L., Wang Y., Khairova R., Blumenthal R., Tragon T., Hunsberger J. G., Machado-Vieira R., Drevets W., Wang Y. T., Manji H. K. (2010). A kinesin signaling complex mediates the ability of GSK-3beta to affect mood-associated behaviors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11573–11578 10.1073/pnas.1006586107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edagawa Y., Saito H., Abe K. (1998). 5-HT1A receptor-mediated inhibition of long-term potentiation in rat visual cortex. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 349, 221–224 10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00286-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito E., Di Matteo V., Di Giovanni G. (2008). Serotonin-dopamine interaction: an overview. Prog. Brain Res. 172, 3–6 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00901-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X., Yu S. X., Lu Y., Bast R. C., Jr., Woodgett J. R., Mills G. B. (2000). Phosphorylation and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 by protein kinase A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 11960–11965 10.1073/pnas.220413597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink K. B., Gothert M. (2007). 5-HT receptor regulation of neurotransmitter release. Pharmacol. Rev. 59, 360–417 10.1124/pr.107.07103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainetdinov R. R., Premont R. T., Bohn L. M., Lefkowitz R. J., Caron M. G. (2004). Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors and neuronal functions. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 107–144 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaisina I. N., Gallier F., Ougolkov A. V., Kim K. H., Kurome T., Guo S., Holzle D., Luchini D. N., Blond S. Y., Billadeau D. D., Kozikowski A. P. (2009). From a natural product lead to the identification of potent and selective benzofuran-3-yl-(indol-3-yl)maleimides as glycogen synthase kinase 3beta inhibitors that suppress proliferation and survival of pancreatic cancer cells. J. Med. Chem. 52, 1853–1863 10.1021/jm801317h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelber E. I., Kroeze W. K., Willins D. L., Gray J. A., Sinar C. A., Hyde E. G., Gurevich V., Benovic J., Roth B. L. (1999). Structure and function of the third intracellular loop of the 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptor: the third intracellular loop is alpha-helical and binds purified arrestins. J. Neurochem. 72, 2206–2214 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami A., Baruscotti M., Robinson R. B., Hen R. (1997). Adenovirus-mediated expression of 5-HT1B receptors in cardiac ventricle myocytes; coupling to inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 340, 259–266 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01404-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode N., Hughes K., Woodgett J. R., Parker P. J. (1992). Differential regulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta by protein kinase C isotypes. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 16878–16882 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould T. D., Einat H., Bhat R., Manji H. K. (2004). AR-A014418, a selective GSK-3 inhibitor, produces antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 7, 387–390 10.1017/S1461145704004535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon J., Hoyer D. (2008). Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors. Behav. Brain Res. 195, 198–213 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper C., Markevich V., Plattner F., Killick R., Schofield E., Engel T., Hernandez F., Anderton B., Rosenblum K., Bliss T., Cooke S. F., Avila J., Lucas J. J., Giese K. P., Stephenson J., Lovestone S. (2007). Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition is integral to long-term potentiation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 81–86 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05245.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer D., Hannon J. P., Martin G. R. (2002). Molecular, pharmacological and functional diversity of 5-HT receptors. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 71, 533–554 10.1016/S0091-3057(01)00746-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer D., Martin G. (1997). 5-HT receptor classification and nomenclature: towards a harmonization with the human genome. Neuropharmacology 36, 419–428 10.1016/S0028-3908(97)00036-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiung S. C., Tamir H., Franke T. F., Liu K. P. (2005). Roles of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and Akt signaling in coordinating nuclear transcription factor-kappaB-dependent cell survival after serotonin 1A receptor activation. J. Neurochem. 95, 1653–1666 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03496.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiung S. C., Tin A., Tamir H., Franke T. F., Liu K. P. (2008). Inhibition of 5-HT1A receptor-dependent cell survival by cAMP/protein kinase A: role of protein phosphatase 2A and Bax. J. Neurosci. Res. 86, 2326–2338 10.1002/jnr.21676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakab R. L., Goldman-Rakic P. S. (1998). 5-Hydroxytryptamine2A serotonin receptors in the primate cerebral cortex: possible site of action of hallucinogenic and antipsychotic drugs in pyramidal cell apical dendrites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 735–740 10.1073/pnas.95.2.735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Januel D., Massot O., Poirier M. F., Olie J. P., Fillion G. (2002). Interaction of lithium with 5-HT(1B) receptors in depressed unipolar patients treated with clomipramine and lithium versus clomipramine and placebo: preliminary results. Psychiatry Res. 111, 117–124 10.1016/S0165-1781(02)00136-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Farley N. N., Kertesy S. B., Dubyak G. R., Cowen D. S. (2005). Enhanced activation of Akt and extracellular-regulated kinase pathways by simultaneous occupancy of Gq-coupled 5-HT2A receptors and Gs-coupled 5-HT7A receptors in PC12 cells. J. Neurochem. 92, 72–82 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02832.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jope R. S., Johnson G. V. W. (2004). The glamour and gloom of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 95–102 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaidanovich-Beilin O., Milman A., Weizman A., Pick C. G., Eldar-Finkelman H. (2004). Rapid antidepressive-like activity of specific glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor and its effect on beta-catenin in mouse hippocampus. Biol. Psychiatry 55, 781–784 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S., VanderSpek S. C., Brownlee B. A., Nobrega J. N. (2003). Antipsychotic dosing in preclinical models is often unrepresentative of the clinical condition: a suggested solution based on in vivo occupancy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 305, 625–631 10.1124/jpet.102.046987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennett G. A., Dourish C. T., Curzon G. (1987). Antidepressant-like action of 5-HT1A agonists and conventional antidepressants in an animal model of depression. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 134, 265–274 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90357-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. J., Jung M. W. (2006). Neural circuits and mechanisms involved in Pavlovian fear conditioning: a critical review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 30, 188–202 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein P. S., Melton D. A. (1996). A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 8455–8459 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman G. L., Cole J. O. (1965). Clinical pharmacology of imipramine and related antidepressant compounds. Pharmacol. Rev. 17, 101–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlovsky N., Amar S., Belmaker R. H., Agam G. (2006). Psychotropic drugs affect Ser9-phosphorylated GSK-3beta protein levels in rodent frontal cortex. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 9, 337–342 10.1017/S1461145705006097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landolt H. P., Wehrle R. (2009). Antagonism of serotonergic 5-HT2A/2C receptors: mutual improvement of sleep, cognition and mood? Eur. J. Neurosci. 29, 1795–1809 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06718.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz R. J., Shenoy S. K. (2005). Transduction of receptor signals by beta-arrestins. Science 308, 512–517 10.1126/science.1109237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone A. M., Errico M., Lin S. L., Cowen D. S. (2000). Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and Akt by human serotonin 5-HT(1B) receptors in transfected BE(2)-C neuroblastoma cells is inhibited by RGS4. J. Neurochem. 75, 934–938 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750934.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardo E. D., Hen R. (2008). Anxiety as a developmental disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 134–140 10.1038/sj.npp.1301569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wang X., Meintzer M. K., Laessig T., Birnbaum M. J., Heidenreich K. A. (2000). Cyclic AMP promotes neuronal survival by phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 9356–9363 10.1128/MCB.20.5.1784-1796.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Jope R. S. (2010). Is glycogen synthase kinase-3 a central modulator in mood regulation? Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 2143–2154 10.1038/npp.2010.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Rosborough K. M., Friedman A. B., Zhu W., Roth K. A. (2007). Regulation of mouse brain glycogen synthase kinase-3 by atypical antipsychotics. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 10, 7–19 10.1017/S1461145705006425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhu W., Roh M. S., Friedman A. B., Rosborough K., Jope R. S. (2004). In vivo regulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK3beta) by serotonergic activity in mouse brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 1426–1431 10.1038/sj.npp.1300439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang M. H., Chuang D. M. (2006). Differential roles of glycogen synthase kinase-3 isoforms in the regulation of transcriptional activation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30479–30484 10.1074/jbc.M512240200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R. N., McQuade R. D., Carson W. H., Hennicken D., Fava M., Simon J. S., Trivedi M. H., Thase M. E., Berman R. M. (2008). The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a second multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 28, 156–165 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31816774f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek G. J., Carpenter L. L., McDougle C. J., Price L. H. (2003). Synergistic action of 5-HT2A antagonists and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 28, 402–412 10.1038/sj.npp.1300057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz J. S., Brown C. S., Moore T. R. (1999). Atypical antipsychotics. Part I: Pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy. Ann. Pharmacother. 33, 73–85 10.1345/aph.17215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]