Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Prevention of the periodontal disease progression is the primary goal of periodontal therapy. When conventional therapy is found inadequate to attain periodontal health in chronic periodontitis, local antimicrobial agents have been used as an adjunct with scaling and root planning (SRP) which has reproduced encouraging results. Hence, this study was undertaken to evaluate the new sustained released local drug Chlosite clinically and microbiologically in smokers and non-smokers.

Materials and Methods:

The patients were grouped into experimental group A treated with SRP plus Chlosite (SRP + CHL), experimental group B treated with Chlosite alone (CHL), and control group C treated only with SRP alone. A total number of 141 sites from six patients (67 sites from three non-smoker patients and 74 sites from three smoker patients) participated in this study. The clinical parameters, Plaque index (PI), Gingival index (GI), Bleeding index (BI), and Relative attachment level (RAL), were recorded and subgingival plaque samples were collected and subjected to microbiological analysis.

Results:

On comparison of smokers and non-smokers, in SRP group, non-smokers showed a higher reduction in BI and GI and smokers showed a higher reduction in PI. There was no significant gain in RAL of both smokers and non-smokers. In SRP + CHL group, non-smokers showed a higher reduction in relation to BI and GI and smokers showed a higher reduction in relation to PI. There was no significant gain in RAL of both smokers and non-smokers. In CHL group, both smokers and non-smokers showed a nonsignificant reduction in BI, GI, and RAL, but smokers showed a significant reduction in PI as compared with non-smokers. All the groups showed reduction in the microbial count of Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Tannerella forsythia which were found to be statistically not significant when it was compared between non-smokers and smokers.

Interpretation and Conclusion:

In this study, all treatment groups were found to be efficacious in the treatment of periodontal disease as demonstrated by improvement in PI, GI, BI, and RAL. Combination of SRP and Chlosite resulted in added benefits compared with the two treatment groups.

Keywords: Chlosite, chronic periodontitis, microbial count, xanthan gel

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, periodontal disease therapy has been directed to altering the periodontal environment to one that is less conducive to the retention of bacterial plaque in the vicinity of gingival tissues. With the increasing awareness of the bacterial etiology of periodontal diseases,[1,2] and in particular the hypothesis that specific bacteria are involved,[3] a more direct approach, using antibacterial agents has become an integral part of the therapeutic armamentarium. Recently, a new sustained local drug delivery chlorhexidine (CHX) with xanthan gel, Chlosite (1.5% of CHX in 0.5 ml of xanthan gel) has been introduced. Therefore, it was deemed important to evaluate the efficacy of this drug clinically and microbiologically in the treatment of chronic periodontitis smoker and non-smoker patients. The objective of the study is to determine the effect of chlosite as a monotherapy, chlosite compared with scaling and root planning (SRP), chlosite with SRP (combination therapy), and to determine the efficacy of chlosite on periodontopathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total number of 141 sites from six patients (67 sites from three non-smoker patients and 74 sites from three smoker patients) with periodontal pockets measuring 5 to 7 mm in different quadrants of mouth were selected, between 20 to 50 years from Outpatient Department of Periodontics College of Dental Sciences, Davangere, Karnataka, India. The Ethical committee of College of Dental Sciences, Davangere, Karnataka, India, approved the study and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

The study included patients diagnosed as suffering from chronic generalized periodontitis. Patient selected had periodontal pocket measuring 5-7 mm in depth in different quadrants of the mouth and signs of bone loss on clinical and radiographic examination were observed [Figure 1]. Pregnant women, nursing mothers, teeth with furcation involvement, and patients with known hypersensitivity reaction to CHX were excluded from the study. These patients did not receive any periodontal therapy for past 6 months and were free of any systemic diseases.[4] The selected sites were randomly divided into 3 groups [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Site selected for study 26 (Mesial)

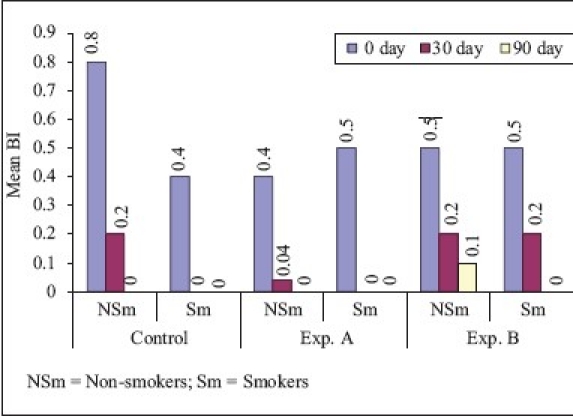

Table 1.

Number of sites involved in treatment modalities of different groups

Prior to SRP, each selected site was subjected to assessment of the following clinical parameter: Plaque index (PI) (Silness and Loe),[5] Gingival index (GI) (Loe and Silness),[6] Bleeding index (BI) (Ainamo and Bay),[7] Relative attachment level (RAL) using UNC-15 periodontal probe, subgingival microbiological plaque samples. The clinical parameters were assessed on day ‘0’, 30th, and 90th day. RAL was assessed only on ‘0’ day and 90th day and microbiological samples were collected on the ‘0’ and 30th day only.

Subgingival microbiological palque samples

Subgingival microbial plaque samples were taken from the periodontal pocket at baseline and on 30th day with the help of fine endodontic paper points. After removing supragingival plaque, two fine endodontic paper points were inserted to the depth of each periodontal pocket for 10 seconds and then transferred to 1 ml Thioglycollate broth (transport medium) and sealed tightly to avoid contamination [Figures 2 and 3]. Samples were processed within 2 days of collection. Once it was received in the laboratory, the sample was mixed thoroughly and 5 μl, each was inoculated using sterile loop onto the following mediums: Enriched blood agar (Porphyromonas gingivalis), Brewer's anaerobic agar (Fusobacterium nucleatum), and Bacteroides bile esculin agar (Tannerella forsythia)[8]

Figure 2.

Subgingival sampling with absorbent paper points

Figure 3.

Transfer of plaque sample to glycolate broth

Procedural steps for chlosite administration

Chlosite was provided as a single-dose syringe with 0.5 ml of xanthan gel, which contains a mixture of chlorhexidine digluconate and chlorhexidine dihydrochloride, in a ratio of 1: 2. The gel was administered in experimental site A (SRP plus Chlosite) and experimental site B (Chlosite only) on ‘0’ day. The periodontal pocket was washed with distilled water and then dried with paper points before subgingival administration of Chlosite. Subgingival administration was accomplished by inserting the single-dose syringe to the base of the periodontal pocket first and then working the way up, until the gingival margin [Figures 4 and 5]. Chlosite undergoes a progressive process of imbibition, and gets physically removed from the application site within 10 to 30 days, making a follow-up visit for removal of the material unnecessary. After the treatment, patients were instructed to avoid eating hard, crunchy or sticky foods for one week, and postpone brushing for 12 hours period, as well as touching the treated areas. Patients should also postpone the use of interproximal cleaning devices for 10 days.

Figure 4.

Occlusal stent with grooves

Figure 5.

Administration of Chlosite

RESULTS

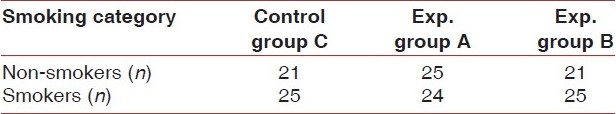

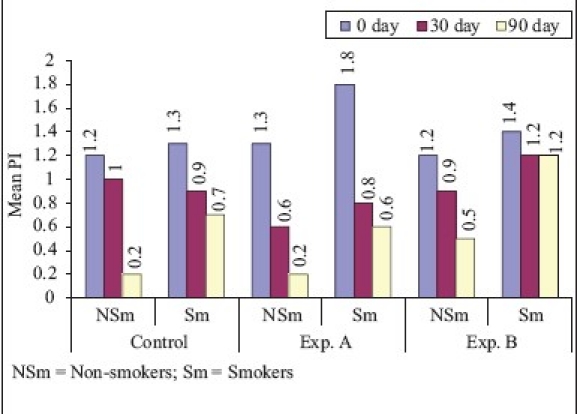

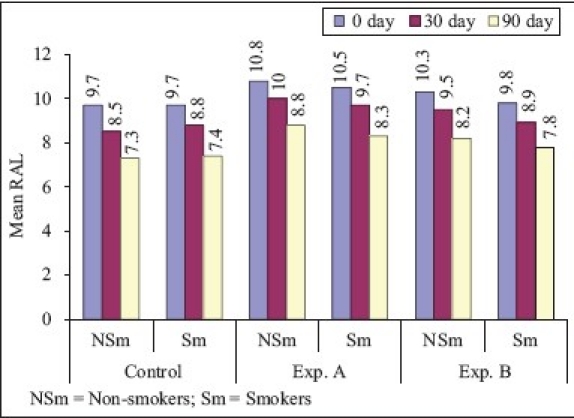

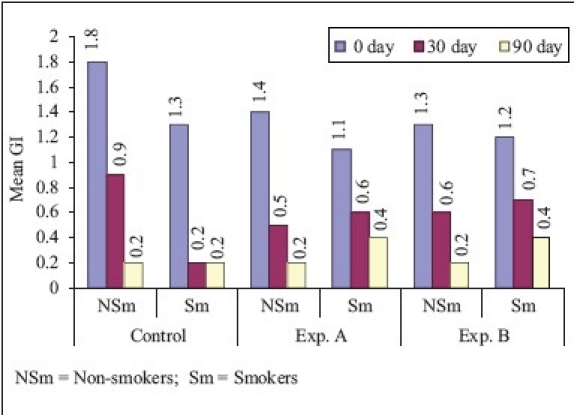

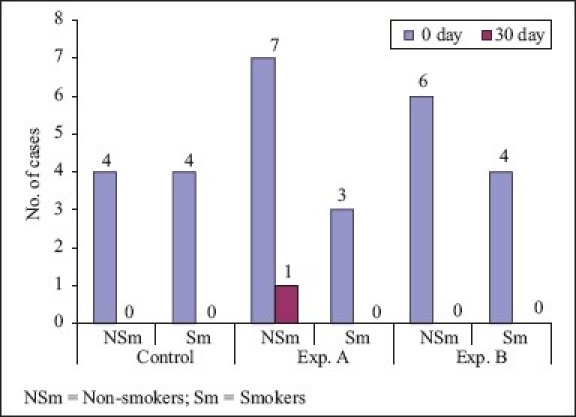

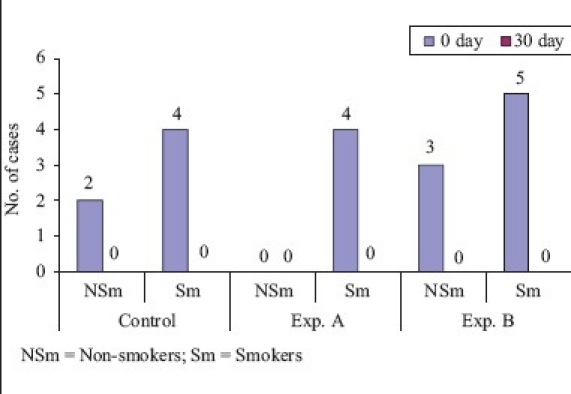

On comparison of non-smokers vs smokers [Graphs 1–4], the mean difference of plaque score between ‘0’ to 90th day for SRP and CHL was statistically significant and for SRP + CHL, it was statistically not significant. The mean difference in GI between ‘0’ to 90th day was statistically significant for SRP and SRP + CHL and statistically not significant for CHL. The mean difference of bleeding score between ‘0’ to 90th day was statistically significant for SRP and statistically not significant for SRP + CHL and CHL. The mean difference in RAL between ‘0’ to 90th day for SRP, SRP + CHL, and CHL was statistically not significant.

Graph 1.

Plaque index (Comparison of smokers and non-smokers)

Graph 4.

Relative attachment level (Comparison of smokers and non-smokers)

Graph 2.

Bleeding index (Comparison of smokers and non-smokers)

Graph 3.

Gingival index (Comparison of smokers and non-smokers)

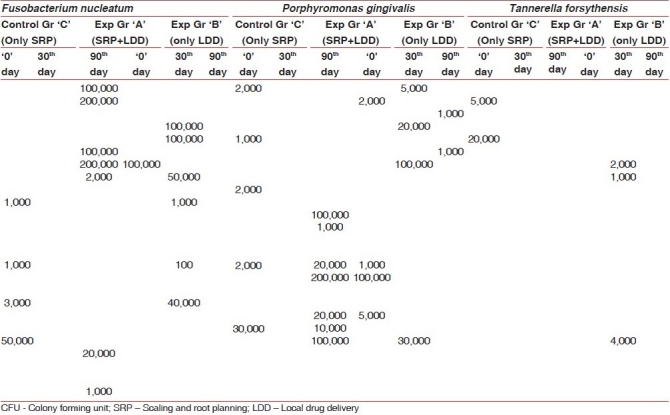

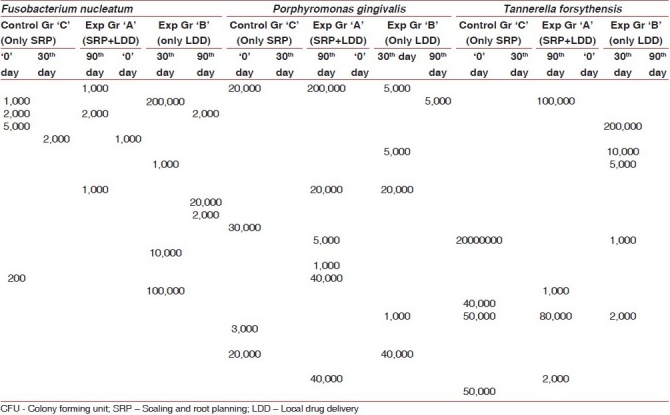

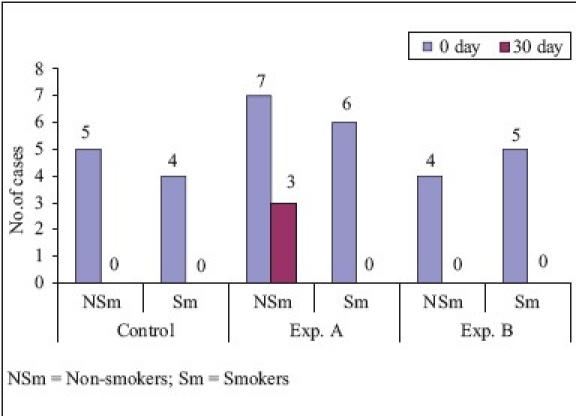

Prevalence of various ous microorganisms at different intervals of studymicroorganisms at different intervals of study period in smokers and non-smokers [Graphs 5–7, Tables 2 & 3 and Figures 6–8].

Graph 5.

Fusobacterium nucleatum (Comparison of smokers and non-smokers)

Graph 7.

Tannerella forsythia (Comparison of smokers and non-smokers)

Table 2.

Microbial profile of non-smokers (CFU)

Table 3.

Microbial profile of smokers (CFU)

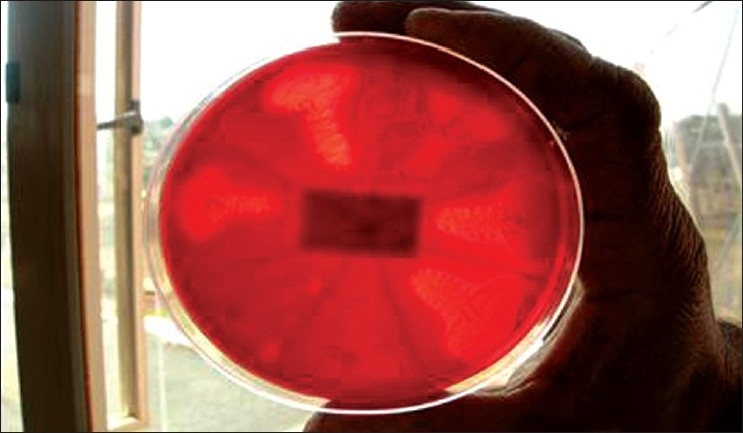

Figure 6.

Blood agar plate showing haemolytic colonies of Porphyromonas gingivalis

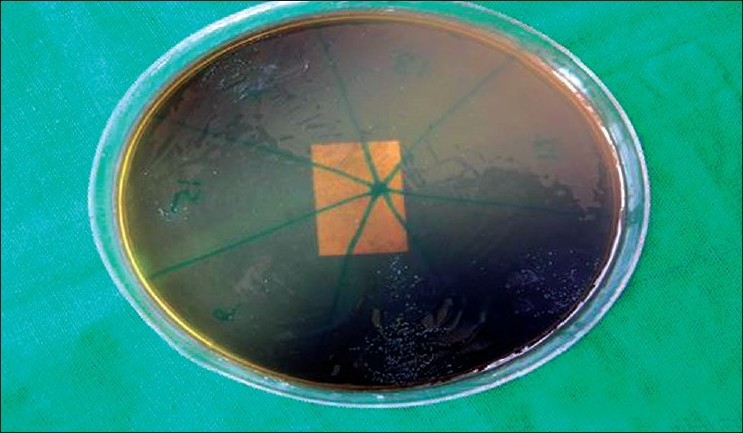

Figure 8.

B.B.E Agar showing colonies of Tannerella forsythia

Graph 6.

Porphyromonas gingivalis (Comparison of smokers and non-smokers)

Figure 7.

Blood agar plate showing colonies of Fusobacterium nucleatum

On comparison of non-smokers to smokers, Fusobacterium nucleatum showed 94% reduction in non-smokers and 100% reduction in smokers, which was statistically not significant. On comparison of non-smokers with smokers, Porphyromonas gingivalis showed 81.2% reduction in non-smokers and 100% reduction in smokers, which was statistically not significant. On comparison of non-smokers with smokers, Tannerella forsythia showed 100% reduction in both groups which was statistically not significant. In smokers, the results of this study are not compared due to paucity of literature on the effect of CHX on smokers.

DISCUSSION

CHX is a widely used broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent to inhibit bacterial growth and, thus, an adjunctive mean to control oral hygiene in patients with periodontal disease. Attempts to prolong the subgingival application of CHX by incorporation of an antiseptic in a gel have not resulted in improved treatment outcomes,[9] However, with the use of chlosite, effective subgingival concentration of CHX can be maintained for several days. The physical properties of xanthan render it an optimum substrate for the formation of a stable gel that is easily extruded from a syringe needle; therefore, xanthan appears to be the best biocompatible vehicle for clinical application.[10]

In non-smokers, the mean reduction in PI from ‘0’ to 90th day was 83.3 and 84.6% for SRP and SRP + CHL, respectively. However, the difference in PI at ‘0’ to 90th day between the two groups was statistically not significant. These findings were similar to the findings of Azmak et al.[11] who studied the effect of subgingival-controlled release delivery of 2.5 mg of CHX chip on clinical parameters of chronic periodontitis patients, in patients receiving SRP + CHX and SRP alone groups. Mean reduction in plaque score from baseline to 90th day for CHL was 58.3%, which was statistically highly significant. In smokers, the mean reduction in plaque score from ‘0’ to 90th day was 46.2, 66.7, and 14.3% in SRP, SRP + CHL, and CHL, respectively, which was statistically highly significant in SRP and SRP + CHL and significant in relation to CHL. On comparison of non-smokers vs smokers, the mean difference of plaque score between ‘0’ to 90th day for SRP and CHL was statistically significant and for SRP + CHL, it was statistically not significant.

In non-smokers, the mean reduction in BI from ‘0’ to 90th day was 100% for SRP and SRP + CHL, respectively. However, the difference in BI at ‘0’ to 90th day between the two groups was statistically significant. These findings are similar to the findings of Pennuti et al.[12] who studied the efficacy of 0.5% CHX gel on the control of gingivitis in mentally handicapped patients over a period of 8 weeks. In smokers, the mean reduction in bleeding score from ‘0’ to 90th day was 100% in SRP, SRP + CHL, and CHL, and it was statistically highly significant in all the above-mentioned three treatment modalities. On comparison of non-smokers vs smokers, the mean difference of bleeding score between ‘0’ to 90 th day was statistically significant for SRP and statistically not significant for SRP + CHL and CHL.

In non-smokers, the mean reduction in gingival score from ‘0’ to 90th day was 88.9 and 85.7% for SRP and SRP + CHL, respectively. These findings were similar to that of Unsal et al.[13] who studied the clinical effects of subgingival placement of 1% CHX gel in adult periodontitis patients over a duration of 12 weeks. There was 54.6% mean reduction in gingival score from baseline to 90th day, which was statistically highly significant. In smokers, the mean reduction in gingival score from ‘0’ to 90th day was 84.5, 63.6, and 66.7% which was highly significant for SRP and SRP + CHL, whereas significant for CHL. On comparison of non-smokers vs smokers, the mean difference in GI between ‘0’ to 90th day was statistically significant for SRP and SRP + CHL and statistically not significant for CHL.

In non-smokers, the mean gain in RAL from ‘0’ to 90th day was 24.7 and 18.5% for SRP and SRP + CHL, respectively. These findings were similar to that of Soskolne et al.[14] who studied the changes in probing depth following 2 years of periodontal maintenance therapy including adjunctive controlled release of biodegradable CHX chip. There was 20.4% mean gain in RAL from baseline to 90th day for CHL, which was statistically highly significant. In smokers, the mean gain in RAL from ‘0’ to 90th day was 23.7, 21, and 20.4% for SRP, SRP + CHL, and CHL, respectively, which was highly significant. On comparison of RAL in non-smokers vs smokers, the mean difference in RAL between ‘0’ to 90th day for SRP, SRP + CHL, and CHL was statistically not significant.

On comparison of non smokers with smokers Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythis showed reduction which was statistically not significant. The findings for the three bacteria are similar to that of Daneshmand et al.[15]

CONCLUSION

On comparison of smokers and non-smokers, in SRP group, non-smokers showed a higher reduction in BI and GI and smokers showed a higher reduction in PI. There was no significant gain in RAL of both smokers and non-smokers. In SRP + CHL group, non-smokers showed a higher reduction in relation to BI and GI and smokers showed a higher reduction in relation to PI. There was no significant gain in RAL of both smokers and non-smokers. In CHL group, both smokers and non-smokers showed a nonsignificant reduction in BI, GI, and RAL, but smokers showed a significant reduction in PI as compared with non-smokers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Anurag Singh (Chairman), Dr. Snehalata Chaudhary (Secretary) and Dr. Praveen Mehrotra (Principal) of the college (SPPGIDMS, Lucknow) for their contribution and support in this original study. We would like to thank all the faculty members of the department of Periodontology and Implantology, especially Dr. (Prof.) K.K Gupta , Dr. (Prof.) Pradeep Tandon.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Socransky SS. The relationship of bacteria of the etiology of periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 1970;49:203–22. doi: 10.1177/00220345700490020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slots J. Subgingival microflora and periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1979;6:351–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1979.tb01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loesche WJ, Syed SA, Schmidt E, Morrison EC. Bacterial profiles of subgingival plaques in periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1985;56:447–56. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.8.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daneshmand N, Jorgensen MG, Nowzari H, Morrison JL, Slots J. Initial effect of controlled release chlorhexidine on subgingival microorganisms. J Periodontal Res. 2002;37:375–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2002.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal diseases in pregnancy (2) correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;24:747–59. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ainoma J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and laque. Int Dent J. 1975;25:229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konemar EW, Allen SD, Janda WN, Shreeckenberger PC, Winn WC, editors. Color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology; pp. 709–75. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oosterwaal PJ. Comparison of the antimicrobial effect of the application of chlorhexidine gel,amino fluoride gel in debrided periodontal pockets. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:245–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Needleman IG, Smales FC, Martin GP. An investigation of bioadhesion for periodontal and mucosal drug delivery. J Clin Periodontal. 1997;24:394–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azmak N, Atilla G, Luoto H, Sorsa T. The effect of subgingival controlled release delivery of chlorhexidine chip on clinical parameters and matrix metalloproteinase-8 levels in gingival crevicular fluid. J Periodontol. 2002;73:608–15. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.6.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pennuti CM, Saraiva MC, Ferraro A, Falsi D, Cai S, Lotufo RF. Efficacy of a 0.5% chlorhexidine gel on the control of gingivitis in Brazilian mentally handicapped patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:573–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unsal E, Akkaya M, Walsh TF. Influence of a single application of subgingival chlorhexidine gel or tetracycline paste on the clinical parameters of adult periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:351–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soskolne WA, Proskin HM, Stabholz A. Probing depth changes following 2 years of periodontal maintenance therapy including adjunctive controlled release of chlorhexidine. J Periodontol. 2003;74:420–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.4.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daneshmand N, Jorgensen MG, Nowzari H, Morrison JL, Slots J. Initial effect of controlled release chlorhexidine on subgingival microorganisms. J Periodontal Res. 2002;37:375–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2002.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]