Abstract

Background:

The objective of this double-blind clinical trial was to evaluate the effects of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), ketoprofen, on patients with chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

Two similar local drug delivery preparations of a poloxamen gel containing 1.5% ketoprofen and a placebo were indigenously prepared for this purpose. Ten subjects aged 33-55 years with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis were recruited and were monitored for a period of 90 days. Three sites in each patient (total 30 sites) with a probing pocket depth of 5-8 mm were selected and divided randomly into three groups: 1) group A: scaling and rootplaning (SRP) + drug A; 2) group B: SRP + drug B; and 3) group C: SRP. Clinical parameters and blood smear (from intracrevicular blood) were assessed to determine the differential count and Arneth index. All parameters were assessed at baseline, 30 days and 90 days, respectively.

Results:

Highly significant values were achieved for plaque index (P=0.00), and significant values were obtained for gingival index (P=0.044). Reduction in bleeding on probing was found to be highly significant. Probing depth and clinical attachment level showed no inter group variation.

Conclusion:

The results of this double-blind trial indicate that the combined effect of locally delivered ketoprofen with SRP was more effective in controlling periodontal disease than SRP alone.

Keywords: Arneth index, bleeding on probing, ketoprofen gel, placebo

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease caused by microorganisms. The progression of the disease, however, is determined by host factors. One of the mediators that influence this progression is the prostaglandins (PGs) which are formed from arachidionic acid under the influence of cyclooxygenase enzymes. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have shown therapeutic benefits in slowing down the rate of progression of periodontal disease by the effective inhibition of PG synthesis.[1]

Local drug delivery is aimed at site-specific therapy; it helps to avoid systemic complications and at the same time achieve high concentrations of the drug at the diseased site. Most research initially conducted utilized antimicrobial agents. This principle is now applied to NSAIDs. One such NSAID that can be used for this purpose is ketoprofen. This propionic acid derivative exhibits a marked potency relative to other agents in blocking human periodontal PGE2 synthesis in vitro.[2] Other in vitro anti-inflammatory effects of ketoprofen include an anti-bradykinin activity and stabilization of lysosomal membranes. A number of studies have shown that differences in disease susceptibility between patients are primarily due to the fact that endotoxin-stimulated monocytes secreted two to three times more PGE than subjects without disease.[3] Ketoprofen has the added advantage of directly inhibiting monocytes and macrophages, which are predominant cells involved in the synthesis of PGs, thereby modifying the response of the host to the process of inflammation.

For a locally delivered drug to be effective, an adequate concentration of the drug requires to be present at the desired site. The vehicle therefore plays an important role in determining the mode of application as well as obtaining sufficient concentrations. Presently, thermo-reversible hydrogels are the most commonly used vehicle in most pharmaceutical applications.[4]

Arneth index is usually considered to estimate the age of the neutrophil. A number of conditions are present wherein older, multilobed neutrophils have been found. recovering from a longstanding infection has been demonstrated as a possibility.[5]

This study was directed at modulating the host response by utilizing an indigenously prepared anti-inflammatory drug containing ketoprofen. The study was double blinded in order to eliminate the possibility of a bias.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

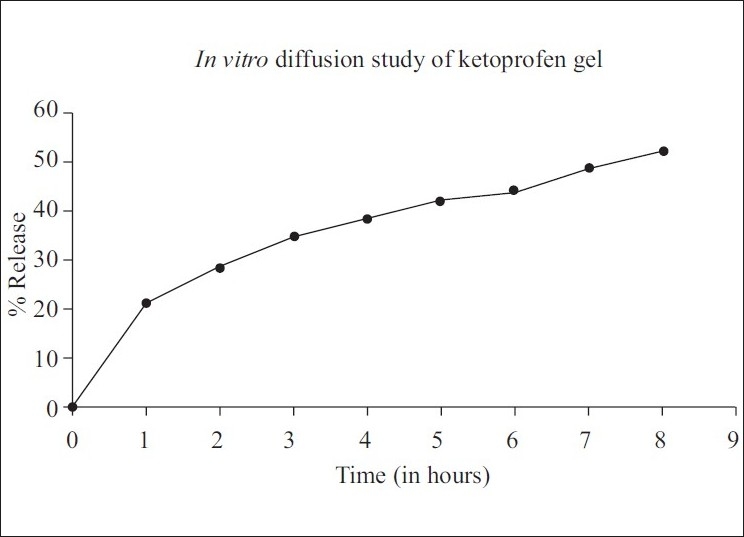

This double-blind clinical trial was conducted to evaluate the effects of the NSAID, ketoprofen, on patients with chronic periodontitis. Two similar local drug delivery preparations of a poloxamen gel containing 1.5% ketoprofen and a placebo were indigenously prepared for this purpose. The drug release pattern of the gel was obtained through static diffusion analysis. This demonstrated an initial burst with approximately 20% of the drug being released in the first hour and the remaining released in a linear manner over a period of 3 days [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Drug release pattern of ketoprofen

The sample constituted 10 subjects aged 33-55 years with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis reporting to the outpatient department, C. I. D. S. Three sites in each patient (total of 30 sites) with a probing depth of 5-8 mm were selected. The patients were recruited and monitored for a period of 90 days. Informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to the initiation of the study.

Patients with a history of allergy to propionic acid derivatives, subjects under chronic treatment with NSAIDs within 1 month, subjects under medication likely to induce gingival hyperplasia, pregnant women and subjects with systemic diseases or habits that might modify the periodontal status were excluded from the study.

All subjects received oral hygiene instructions. Scaling and rootplaning (SRP) was performed and the patients were recalled after a week. Persistent sites were taken into consideration and were randomly divided into three groups in each patient:

Group A: SRP + drug A (ketoprofen, [Figure 2])

Figure 2.

Placement of ketoprofen gel

Group B: SRP + drug B (placebo)

Group C: SRP

The clinical parameters taken into consideration were the plaque index (Silness and Loe), gingival index (Loe and Silness), both of which are considered to determine the oral hygiene status of the patient.

Clinical attachment level (CAL) and Probing pocket depth (PPD) (standardized using an acrylic stent) were measured using a Williams Periodontal Probe [Figures 3 and 4].

Figure 3.

Probing depth in group B (SRP + ketoprofen) at 30 days

Figure 4.

Probing depth in group B at 90 days

Bleeding on Probing (BOP) was recorded as present or absent at the time of conventional probing at each site.

In addition, a blood smear to determine the differential count and Arneth index (from intracrevicular blood) were assessed from the selected three sites. Intracrevicular blood was obtained with the help of capillary tubes [Figure 5]. A systemic count was obtained by a finger prick (peripheral smear) and the values were compared. All parameters were assessed at baseline, 30 days and 90 days.

Figure 5.

Obtaining intracrevicular blood

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was used for all data. Repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze mean changes from baseline. Contingency coefficient was used for data with continuous efficacy variables.

RESULTS

The overall oral hygiene status showed a considerable improvement. Highly significant values were achieved for plaque index (P=0.00), and significant values were obtained for gingival index (P=0.044).

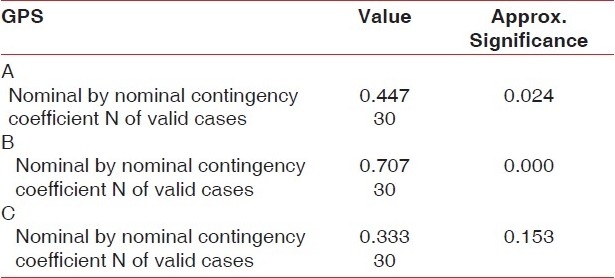

BOP which was measured by contingency coefficient showed a mean reduction of 86.7% in relation to group B (SRP + ketoprofen) (P=0.000), which was found to be highly significant, versus 33.3% (P=0.024) for group A and 20.0% (P=0.15) in group C.

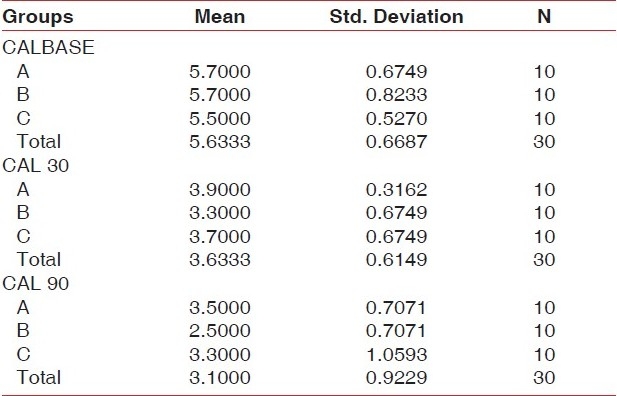

The overall reduction in probing depth was statistically significant (P=0.001) and although group B (SRP + ketoprofen) demonstrated the greatest reduction in probing depth inter-group variations were not found to be statistically significant [Table 1].

Table 1.

Symmetric measure showing levels of significance

The same pattern was observed when changes in CAL from baseline were compared. Clinical attachment gain was greatest in relation to the ketoprofen group, but failed to show statistically significant inter-group variations [group A (SRP + placebo) 2.5 mm; group B (SRP + ketoprofen) 3.2 mm; group C (SRP) 2.8 mm] [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical attachment levels in three site

Differential count in all the three sites did not show any variation and was consistent with the systemic count.

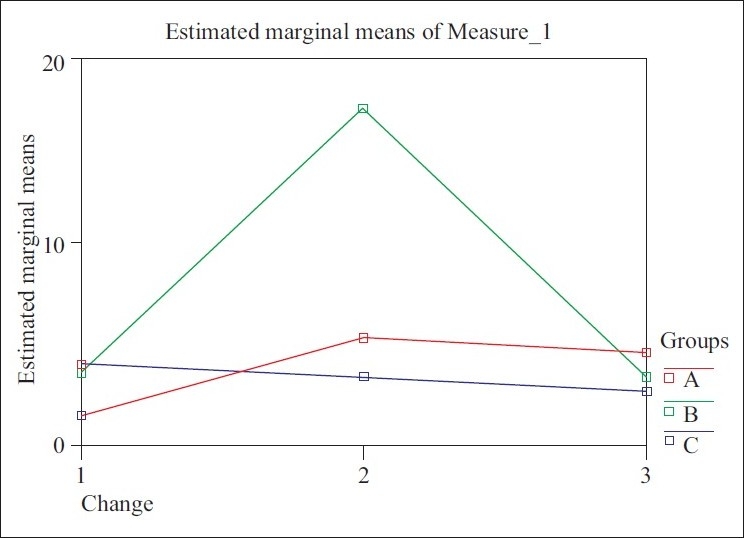

The Arneth index demonstrated a statistically significant change in group B (SRP + ketoprofen) at 30 days, wherein the number of hyper-segmented neutrophils had increased (P<0.01) and these values returned to normal at 90 days [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Graphic representation of Arneth index

DISCUSSION

The current concept of periodontal disease pathogenesis states that microorganisms and their products are capable of inducing inflammatory mediators and the resulting inflammation presents as the hallmark of the disease. PGs formed by the arachidionic acid-cyclooxygenase pathway are one of the key mediators of the disease. Two isoforms of the enzyme cyclooxygenase exist: cox-1 is constitutively expressed and the resulting PGs are responsible for physiological functions (e.g. gastric mucosal secretions, renal homeostasis) and cox-2 is inducible and is said to be produced during inflammation.[2] NSAIDs, with the exception of selective cox-2 inhibitors, inhibit both the isoforms of cyclooxygenase, resulting in adverse effects (gastritis, peptic ulcers, impaired renal function).

In previous reports, use of NSAIDs to control inflammation and as an adjunct to conventional periodontal therapy[1,2] has proven beneficial in comparison with controls. The drawbacks of systemic NSAIDs can be avoided by using a local drug delivery that allows the concentration of a particular drug at the desired site. Ketoprofen, a propionic acid derivative, has been found to be effective against a number of inflammatory conditions and is currently under investigation as a potential adjunct to conventional periodontal therapy.[2] Besides its ability to block the cyclooxygenase pathway, in vitro reports have also demonstrated an anti-lipoxygenase activity,[2] and hence the added ability of the drug to inhibit leukotriene formation.

In this study, a local drug delivery system containing 1.5% ketoprofen gel was used in conjunction with SRP in order to assess periodontal outcomes in subjects with chronic periodontitis.

The results of this double-blind clinical trial of 10 patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis at 30 and 90 days following SRP and oral hygiene index (OHI) indicate that the overall oral hygiene status showed considerable improvement (P=0.00 for plaque index; P=0.044 for gingival index).

BOP is considered the first clinical sign that denotes inflammation, and is therefore a valuable indicator in assessing the status of the inflammatory component.[10] All sites treated with SRP showed improvement at 30 and 90 days, respectively. At 90 days, reduction of BOP with ketoprofen was found to be highly significant (P=0.00) in comparison with the other two groups. Results in relation to group A (SRP + placebo) were found to be significant (P=0.24), while BOP did not achieve statistically significant values in relation to group C, indicating that group B (SRP + ketoprofen) demonstrated a significant reduction in the clinical signs of gingival inflammation. This is in conjunction with previous reports of reduced inflammatory components following the application of a similar gel.[2]

The presence of increased levels of PGs has been implicated in the loss of attachment and alveolar bone loss.[6] Controlling PG synthesis can therefore reduce bone loss and maintain attachment levels.[7]

Recently published data utilizing different concentrations of a topically applied ketoprofen gel demonstrated decreased PG levels in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF).[2] A number of investigations using anti-inflammatory medications as an adjunct to SRP have reported significant differences between test and control groups with regard to PPD, CAL and loss of alveolar bone.[1]

In this study, although there was a highly significant overall gain in CAL and reduction of PPD, inter-group variations were not found to be statistically significant. This variability in responsiveness may be attributed to differences in study design in terms of duration and due to the lack of a standardized drug regimen.

The differential count was estimated in order to assess the effect of ketoprofen on monocytes (in vitro studies have demonstrated that ketoprofen can suppress monocytes and macrophage).[9] This study did not demonstrate any inter-group variation in the proportion of WBCs which remained constant throughout the study. This difference may be attributed to the fact that this was an in vivo study.

Arneth's index is the result of computations based on nuclear structures. It is a method of estimating the relative age of a neutrophil. Neutrophils with less lobes are younger forms, while those with greater number of lobes represent older cells. An increase in the number of lobes (shift to right) was demonstrated at 30 days following application of drug B. The values returned to normal when examined at 90 days. During recovery from an infection, there is a shift to the right. This is because the number of young cells entering the site is decreased and the cells already present are somewhat effected by the toxemia of the infectious process.[5] Another explanation could be the fact that ketoprofen is capable of inhibiting interleukin (IL)-8-induced chemotaxis.[8]

As far as the limitations of this study are concerned, a larger sample size with a longer duration of follow-up would have proven to be beneficial. Since NSAIDs are currently in an experimental stage, a standardized drug regimen would have established desired concentrations of the drug within the gingival crevice for the required period of time.

CONCLUSION

Ketoprofen has important anti-inflammatory properties, and is therefore beginning to be utilized in periodontics. In this study, locally delivered ketoprofen in conjunction with mechanical periodontal therapy has proven to be beneficial in controlling the clinical signs of inflammation. However, further long-term studies are required to substantiate this effect of ketoprofen as an adjunct to conventional periodontal therapy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jeffcoat MK, Reddy MS, Haigh S, Buchanan W, Doyle MJ, Meredith MP, et al. A comparison of topical ketrolac, systemic flurbiprofen, and placebo for the inhibition of bone loss in adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1995;66:329–38. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.5.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paquette DW, Lawrence HP, Maynor GB, Wilder R, Binder TA, Troullos E, et al. Pharmacodynamic effects of ketoprofen on crevicular fluid prostanoids in adult periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:558–66. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027008558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrisons W, Nichols FC. LPS elicited secretory responses in monocytes: Altered release of PGE2 but not IL-1 beta in patients with adult periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 1989;24:88–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1989.tb00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escobar-Chávez JJ, López-Cervantes M, Naïk A, Kalia YN, Quintanar-Guerrero D, Ganem-Quintanar A. Applications of thermo-reversible Pluronic F -127 pharmaceutical formulations. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2006;9:339–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns L. Studies in osteopathic sciences, cells of the blood. [Last cited on 2011 Jan 03];4 chapter 4, version 5.0 Available from: http://www.mcmillinmedia.com/eamt/files/burns4/bur4ch04.html . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Offenbacher S, Odle BM, Van Dyke TE. The use of crevicular fluid prostaglandin E2 levels as predictor of periodontal attachment loss. J Periodontal Res. 1986;21:101–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1986.tb01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldman RS, Szeto B, Chauncey H, Goldhaber P. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the reduction of human alveolar bone loss. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:131–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb02201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bizzari C, Paglei S, Brandolini L. Selective inhibition of il-8 induced neutrophil chemotaxis by ketoprofen isomers. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:1429–37. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00610-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackman BR, Moore JN, Barton MH, Morris DD. Comparison of the effects of ketoprofen and fluxin meglumine on the in vitro response of equine peripheral blood monocytes to bacterial endotoxin. Can J Vet Res. 1994;58:138–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman, Takei, Klokkevold, Carranza . 10th ed. St Louis, Missouri: Saunders; 2006. Text book on Clinical Periodontology. [Google Scholar]