Abstract

Background

Antiretroviral therapy that reduces viral replication could limit the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in serodiscordant couples.

Methods

In nine countries, we enrolled 1763 couples in which one partner was HIV-1–positive and the other was HIV-1–negative; 54% of the subjects were from Africa, and 50% of infected partners were men. HIV-1–infected subjects with CD4 counts between 350 and 550 cells per cubic millimeter were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive antiretroviral therapy either immediately (early therapy) or after a decline in the CD4 count or the onset of HIV-1–related symptoms (delayed therapy). The primary prevention end point was linked HIV-1 transmission in HIV-1–negative partners. The primary clinical end point was the earliest occurrence of pulmonary tuberculosis, severe bacterial infection, a World Health Organization stage 4 event, or death.

Results

As of February 21, 2011, a total of 39 HIV-1 transmissions were observed (incidence rate, 1.2 per 100 person-years; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.9 to 1.7); of these, 28 were virologically linked to the infected partner (incidence rate, 0.9 per 100 person-years, 95% CI, 0.6 to 1.3). Of the 28 linked transmissions, only 1 occurred in the early-therapy group (hazard ratio, 0.04; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.27; P<0.001). Subjects receiving early therapy had fewer treatment end points (hazard ratio, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.88; P = 0.01).

Conclusions

The early initiation of antiretroviral therapy reduced rates of sexual transmission of HIV-1 and clinical events, indicating both personal and public health benefits from such therapy.

Combination antiretroviral therapy decreases the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and improves the survival of infected persons.1,2 Such therapy has been shown to reduce the amount of HIV-1 in genital secretions.3-5 Because the sexual transmission of HIV-1 from infected persons to their partners is strongly correlated with concentrations of HIV-1 in blood6 and in the genital tract,7 it has been hypothesized that antiretroviral therapy could reduce sexual transmission of the virus. Several observational studies have reported decreased acquisition of HIV-1 by sexual partners of patients receiving antiretroviral therapy.8-11 These results have been extrapolated to suggest that the use of early antiretroviral therapy could reduce the spread of the virus in a population.12 Some ecologic studies have shown a reduction in the incidence of new cases of HIV-1 after expanded use of antiretroviral therapy.13,14

The effect of the timing of the initiation of antiretroviral therapy on clinical and microbiologic outcomes has been controversial in evaluations of the benefit of therapy and of the associated short- and long-term complications and costs. For many years, antiretroviral therapy was delayed until a patient's CD4 count fell below 200 cells per cubic millimeter, which led to frequent opportunistic infections.15 Retrospective analyses of patients with HIV-1 infection who were treated in developed countries have suggested a benefit from early antiretroviral therapy,16-18 although the ability to control for bias in these studies has limits.

To evaluate the effect of combination antiretroviral therapy on the prevention of HIV-1 transmission to uninfected partners and on clinical events in infected persons, the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) conducted a multicontinent, randomized, controlled trial, called HPTN 052, to compare early versus delayed antiretroviral therapy for patients with HIV-1 infection who had CD4 counts between 350 and 550 cells per cubic millimeter and who were in a stable sexual relationship with a partner who was not infected.

Methods

Study Population

We enrolled HIV-1 serodiscordant couples at 13 sites in 9 countries (Gaborone, Botswana; Kisumu, Kenya; Lilongwe and Blantyre, Malawi; Johannesburg and Soweto, South Africa; Harare, Zimbabwe; Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre, Brazil; Pune and Chennai, India; Chiang Mai, Thailand; and Boston). A pilot phase started in April 2005, and enrollment took place from June 2007 through May 2010. Couples were required to have had a stable relationship for at least 3 months, to have reported three or more episodes of vaginal or anal intercourse during this time, and to be willing to disclose their HIV-1 status to their partner. Patients with HIV-1 infection were eligible if their CD4 count was between 350 and 550 cells per cubic millimeter and they had received no previous antiretroviral therapy except for short-term prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. (Full criteria for inclusion and exclusion are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.)

The study protocol, which is also available at NEJM.org, was approved by at least one local institutional review board affiliated with each site, by boards affiliated with collaborating organizations, and by other local regulatory bodies when appropriate (for details, see the Supplementary Appendix). All study participants provided written nformed consent in their local languages, or English, if preferred.

Study Oversight

The study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health, which assumed all sponsor responsibilities through an investigational new drug application with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The antiviral agents that were used in the study were donated by pharmaceutical companies, which were not involved in the design or management of the study. All authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data presented, as well as the fidelity of the report to the study protocol.

Study Design

HIV-1 serodiscordant couples were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either an early or delayed strategy for receipt of antiretroviral therapy. Permuted-block randomization was used with stratification according to site. In the early-therapy group, antiretroviral therapy was initiated in the partner with HIV-1 infection at enrollment. In the delayed-therapy group, therapy was initiated after two consecutive measurements in which the CD4 count was 250 cells per cubic millimeter or less or after the development of an illness related to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). HIV-1–infected participants who had active tuberculosis were excluded, and isoniazid prophylaxis was available, according to local guidelines and practice standards.

After enrollment, study participants were asked to attend three monthly visits, which were followed by quarterly visits unless they became ill or needed additional antiretroviral medications. HIV-1–infected participants who were receiving antiretroviral therapy had one additional visit 2 weeks after starting therapy. HIV-1–uninfected partners were encouraged to return for all visits together for counseling on risk reduction and the use of condoms, for treatment of sexually transmitted infections, and for management of other medical conditions. Some HIV-1–infected participants received trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis, according to local guidelines.

HIV-1–uninfected partners were tested for HIV-1 seroconversion on a quarterly basis. Samples from all seroconversion events were evaluated at a central laboratory, and results were reviewed by an independent HIV end-point committee. Partners with seroconversion were released from the study and referred to a prearranged local clinic for care.

After the initiation of antiretroviral therapy, virologic failure for HIV-1–infected participants was defined as two consecutive plasma HIV-1 RNA measurements of more than 1000 copies per milliliter at 16 weeks or later. Assessment for clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory measurements, interviews about sexual behavior, review of adherence to the antiretroviral regimen (including a self-reported questionnaire and pill counts), and adherence counseling were conducted at each visit. (Details regarding study procedures, including guidelines for adherence counseling, are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.)

Any woman who was pregnant at enrollment or became pregnant was provided antiretroviral therapy appropriate for use during pregnancy at the start of the second trimester. On the basis of the judgment of the site investigator, women in the delayed-therapy group discontinued antiretroviral therapy after delivery or when breast-feeding ended. A new partner could be enrolled with an HIV-1–infected participant if the original partner was released from the study and the new HIV-1– uninfected partner met all inclusion or exclusion criteria.

Antiretroviral Drugs

Study drugs included a combination of lamivudine and zidovudine (Combivir), efavirenz, atazanavir, nevirapine, tenofovir, lamivudine, zidovudine, didanosine, stavudine, a combination of lopinavir and ritonavir (Kaletra and Aluvia), ritonavir, and a combination of emtricitabine and tenofovir (Truvada). A prespecified combination of these drugs was provided to participants at monthly or quarterly visits. Sites could also use locally supplied, FDA-approved drugs if they could be purchased with nonstudy funds. For participants with virologic failure, specified second-line treatment regimens were provided.

Assessment of Linkage of Seroconversions

To assess whether seroconversions were linked, HIV-1 pol gene sequences were generated by population sequencing for study-partner pairs and for 10 additional HIV-infected local control subjects for each relevant site. Sequences were analyzed with the use of phylogenetic methods. The probability of linkage was also assessed with the use of Bayes' theorem to compare the genetic similarity of HIV-1 from partner pairs with the genetic similarity of HIV-1 from local control subjects. In some cases, HIV-1 samples from partner pairs were analyzed with the use of ultra-deep pyrosequencing of the gp41 region.19

Statistical Analysis

We determined that an enrollment of 1750 serodiscordant couples would provide a power of at least 87% to detect a 39% reduction in the incidence of HIV-1 transmission to uninfected partners in the early-therapy group, as compared with the delayed-therapy group (primary prevention end point). By the end of the trial, we anticipated a total of 188 transmission incidences, with cumulative incidence rates of 8.3% in the early-therapy group and 13.2% in the delayed-therapy group, for a total duration of 6.5 years, with an accrual period of 1.5 years and a 5% annual loss to follow-up. The sample size of 1750 would also provide a power of 92% to show that early initiation of antiretroviral therapy provided at least a 20% reduction in the rate of serious clinical events associated with HIV-1 infection, which included death, a World Health Organization (WHO) stage 4 event, or a severe bacterial infection or pulmonary tuberculosis (primary clinical end point). By the end of the trial, we anticipated a total of 234 such clinical events, with cumulative incidence rates of 8.7% in the early-therapy group and 18.0% in the delayed-therapy group.

The study was reviewed twice each year by an independent NIAID multinational data and safety monitoring board. To guide the board in its recommendations regarding trial continuation, a composite monitoring end point was developed to include the occurrence of either death or WHO stage 4 events (excluding esophageal candidiasis) in HIV-1–infected participants or the transmission of HIV-1 to uninfected partners, whichever occurred first in the discordant couple. These were the events that were considered to have the greatest clinical effect on both the HIV-1–infected participant and the uninfected partner. A Lan–DeMets implementation of an O'Brien–Fleming monitoring boundary was used to evaluate the interim data with respect to this composite end point.20,21 An early termination would be indicated if there were conclusive evidence to rule out a hazard ratio of 0.80 or more in the early-therapy group. Interim analyses were planned when approximately 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of a total 340 composite events were observed.

We used the Kaplan–Meier method to calculate event-free probabilities and person-year analysis for incidence rate for a given year. We also used Cox regression to estimate relative risks, which were expressed as hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals, and to provide adjustment for potential prognostic factors, such as the infected participant's baseline CD4 count, baseline plasma HIV-1 RNA concentration, and sex. The same Cox analyses were performed on linked transmissions, any transmissions, clinical events, and composite monitoring events. We used chi-square tests to compare the frequencies of adverse events. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The cutoff was adjusted for multiple comparisons in trial-monitoring boundaries.

Results

Study Participants

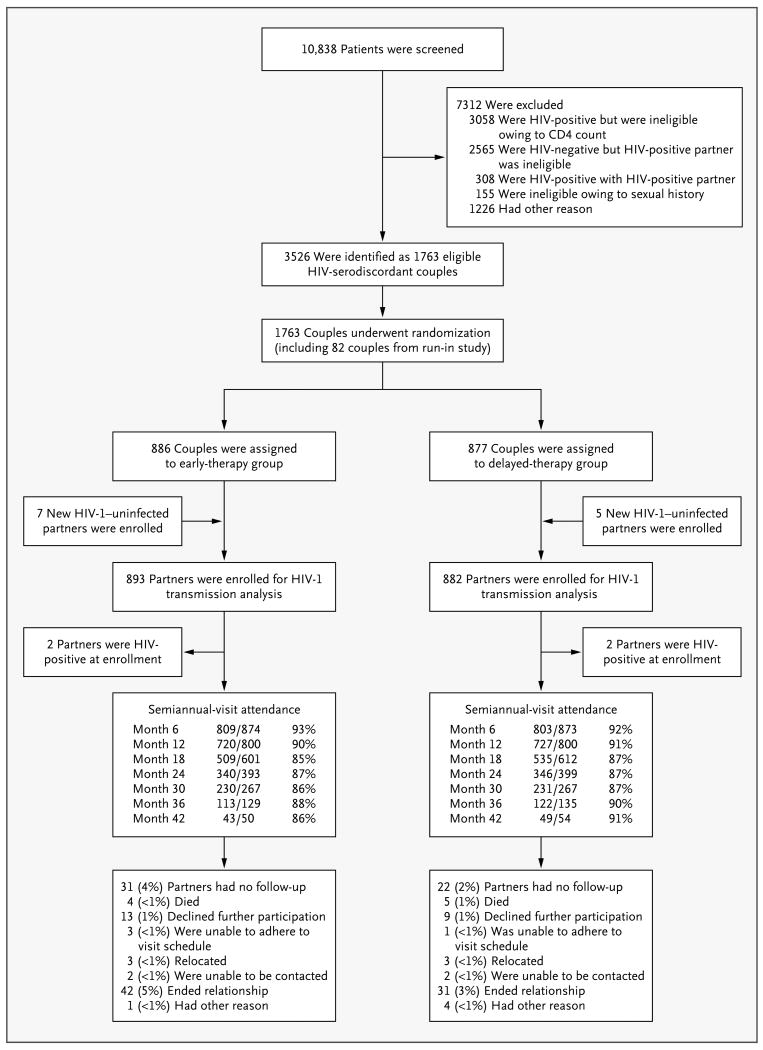

A total of 10,838 persons were screened in order to enroll 1763 HIV-1–serodiscordant couples; 886 couples were randomly assigned to the early-therapy group and 877 to the delayed-therapy group) (Fig. 1, and the Supplementary Appendix). Twelve additional HIV-1–uninfected partners were enrolled as the result of a new relationship.

Figure 1. Enrollment and Outcomes.

This trial profile describes recruitment of couples from the general population, randomization, HIV-1–uninfected partner's enrollment, seroconversion at baseline, retention, and loss-to-follow-up for assessment of the primary end point of linked HIV-1 transmission. Enrolled partners were followed on a quarterly-visit schedule, although attendance at semiannual visits is shown.

The majority of couples (97%) were heterosexual, and 94% were married; 50% of HIV-1–infected participants were men. The majority of participants (61%) were between 26 and 40 years of age. At enrollment, 1291 of HIV-1–infected participants (73%) and 1281 of HIV-1–uninfected partners (72%) reported having had at least one sexual encounter during the previous week. During the same period, 5% and 6%, respectively, reported having unprotected sex. The median CD4 counts for the HIV-1–infected partners were 442 cells per cubic millimeter in the early-therapy group and 428 cells per cubic millimeter in the delayed-therapy group. The median log10 plasma viral load was 4.4 in each study group. Participants in the two study groups were similar in educational status, self-reported sexual behavior, and rate of condom use (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Participants*.

| Characteristic | HIV-1–Infected Participants | HIV-1–Uninfected Participants† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Therapy (N = 886) |

Delayed Therapy (N = 877) |

Early Therapy (N = 893) |

Delayed Therapy (N = 882) |

|

| Demographic | ||||

|

| ||||

| Female sex — no. (%) | 432 (49) | 441 (50) | 441 (49) | 418 (47) |

|

| ||||

| Age group — no. (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| 18–25 yr | 145 (16) | 161 (18) | 154 (17) | 174 (20) |

|

| ||||

| 26–40 yr | 556 (63) | 547 (62) | 537 (60) | 526 (60) |

|

| ||||

| >40 yr | 185 (21) | 169 (19) | 202 (23) | 182 (21) |

|

| ||||

| Education level — no. (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| No schooling | 101 (11) | 69 (8) | 112 (13) | 77 (9) |

|

| ||||

| Primary schooling | 360 (41) | 347 (40) | 317 (35) | 344 (39) |

|

| ||||

| Secondary schooling | 346 (39) | 388 (44) | 373 (42) | 367 (42) |

|

| ||||

| Postsecondary schooling | 79 (9) | 72 (8) | 91 (10) | 93 (11) |

|

| ||||

| Missing data | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

|

| ||||

| Marital status — no. (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Single | 49 (6) | 38 (4) | 53 (6) | 43 (5) |

|

| ||||

| Married or living with partner | 833 (94) | 833 (95) | 834 (93) | 833 (94) |

|

| ||||

| Widowed, separated, or divorced | 4 (<1) | 6 (1) | 6 (1) | 6 (1) |

|

| ||||

| Region — no. (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| North or South America | 142 (16) | 136 (16) | 145 (16) | 139 (16) |

|

| ||||

| Asia | 267 (30) | 264 (30) | 268 (30) | 264 (30) |

|

| ||||

| Africa | 477 (54) | 477 (54) | 480 (54) | 479 (54) |

|

| ||||

| Sexual activity — no. (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Any unprotected sex in past week | 37 (4) | 51 (6) | 49 (5) | 53 (6) |

|

| ||||

| No. of sex partners in past 3 mo | ||||

|

| ||||

| 0–1 | 831 (94) | 833 (95) | 863 (97) | 844 (96) |

|

| ||||

| 2–4 | 48 (5) | 41 (5) | 29 (3) | 36 (4) |

|

| ||||

| >4 | 7 (1) | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

|

| ||||

| Missing data | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

|

| ||||

| No. of sexual encounters in past week | ||||

|

| ||||

| 0 | 246 (28) | 225 (26) | 253 (28) | 240 (27) |

|

| ||||

| 1–2 | 430 (49) | 438 (50) | 410 (46) | 433 (49) |

|

| ||||

| 3–4 | 156 (18) | 158 (18) | 180 (20) | 151 (17) |

|

| ||||

| >4 | 54 (6) | 55 (6) | 50 (6) | 57 (6) |

|

| ||||

| Missing data | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

|

| ||||

| Clinical | ||||

|

| ||||

| CD4 count — no./mm3 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Median | 442 | 428 | ||

|

| ||||

| Interquartile range | 373–522 | 357–522 | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| Plasma RNA viral load — no. (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| <400 copies/ml | 54 (6) | 43 (5) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| 400–1000 copies/ml | 24 (3) | 33 (4) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| 1001–10,000 copies/ml | 212 (24) | 183 (21) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| 10,001–100,000 copies/ml | 407 (46) | 432 (49) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| 100,001–1 million copies/ml | 186 (21) | 186 (21) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| Missing data | 3 (<1) | 4 (<1) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| Women reporting previous antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy — no./total no. (%) | 115/432 (27) | 119/441 (27) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| Type of serodiscordancy — no. (%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| HIV-positive man, HIV-negative woman | 436 (49) | 417 (48) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| HIV-positive woman, HIV-negative man | 431 (49) | 441 (50) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| HIV-positive man, HIV-negative man | 18 (2) | 19 (2) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| HIV positive woman, HIV-negative woman | 1 (<1) | 0 | NA | NA |

Data regarding the incidence of sexually transmitted infections are provided in the Supplementary Appendix. HIV denotes human immunodeficiency virus, and NA not applicable.

Some participants with HIV-1 infection had more than one uninfected partner during the study period.

At enrollment, less than 5% of participants had a sexually transmitted infection, and rates and types of infection were similar in the two study groups (see the Supplementary Appendix). A total of 84 of 449 HIV-uninfected male partners (19%) in the early-therapy group and 64 of 460 (14%) in the delayed-therapy group had been circumcised (P = 0.05). New sexually transmitted infections were detected with similar frequency among participants in the early-therapy group and the delayed-therapy group during the study, with 36 and 34 syphilis infections, 6 and 8 gonorrhea infections, 10 and 11 chlamydia infections, and 22 and 19 trichomonas infections, respectively. Among HIV-1–infected participants, a mean of 96% of those in the early-therapy group and 95% of those in the delayed-therapy group reported 100% condom use during the study.

On April 28, 2011, the data and safety monitoring board recommended that the results of the study be released on the basis of data collection through February 21, 2011. At that time, 90% of couples remained enrolled in the study, with a median follow-up of 1.7 years; the total number of person-years of follow-up was 1585 in the early-therapy group and 1567 in the delayed-therapy group. The expected effect of early versus delayed antiretroviral therapy on log10 plasma viral load and CD4 counts in the HIV-1–infected participants was observed shortly after enrollment. By 3 months after randomization, 89% of the participants in the early-therapy group had a plasma viral load of less than 400 copies per milliliter, as compared with 9% in the delayed-therapy group. CD4 counts in the early-therapy group rose after the initiation of antiretroviral therapy, from a median of 442 cells per cubic millimeter at enrollment to 603 cells per cubic millimeter by 12 months, and the counts continued to rise throughout the follow-up period (see the Supplementary Appendix). A modest decline in CD4 counts was observed in the delayed-therapy group, from a median of 428 cells per cubic millimeter at enrollment to 399 cells per cubic millimeter by 12 months. A total of 21% of HIV-1–infected participants in the delayed-therapy group began taking antiretroviral therapy after a median of 42 months. Among all participants, 72% received a combination of zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz (see the Supplementary Appendix). Adherence to the study regimen of at least 95% (as measured by pill count) was observed in 79% of participants in the early-therapy group and in 74% of those in the delayed-therapy group. Details with respect to regimens of antiretroviral therapy and pill counts are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Virologic failure was observed in 45 of 886 participants (5%) in the early-therapy group and in 5 of 184 participants in the delayed-therapy group who initiated antiretroviral therapy (3%) (P = 0.23). Of all treated participants, 66% initiated a second-line regimen.

Primary Prevention Outcome

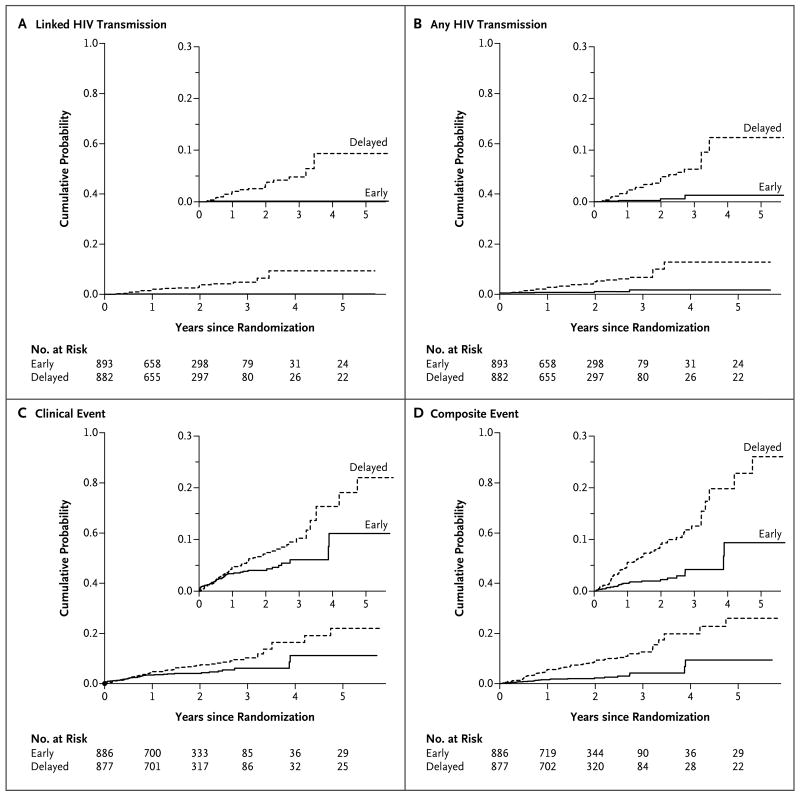

A total of 39 HIV-1 transmission events were observed (incidence rate, 1.2 per 100 person-years; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.9 to 1.7), with 4 events in the early-therapy group (incidence rate, 0.3 per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 0.1 to 0.6) and 35 events in the delayed-therapy group (incidence rate, 2.2 per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 1.6 to 3.1), for a hazard ratio in the early-therapy group of 0.11 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.32; P<0.001) (Table 2 and Fig. 2; also see the Supplementary Appendix for details regarding the incidence of transmission). Through viral genetic analysis, 28 transmissions were linked to the HIV-1–infected participant (incidence rate, 0.9 per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 0.6 to 1.3), with 1 transmission in the early-therapy group (incidence rate, 0.1 per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 0.0 to 0.4) and 27 transmissions in the delayed-therapy group (incidence rate, 1.7 per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 1.1 to 2.5), for a hazard ratio in the early-therapy group of 0.04 (95% CI, 0.01 to 0.27; P<0.001). The remaining 11 transmissions (3 in the early-therapy group and 8 in the delayed-therapy group) included 7 transmissions that were unlinked (3 in the early-therapy group and 4 in the delayed-therapy group), 3 transmissions that could not be classified on the basis of available data, and 1 transmission that has not yet been evaluated. The latter 4 transmissions were all in the delayed-therapy group.

Table 2. Incidence of Partner-Linked and Any HIV-1 Transmission and Clinical and Composite Events.

| Variable | Early Therapy | Delayed Therapy | Hazard or Rate Ratio (95% CI)* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Person-yr | Rate (95% CI) |

Events | Person-yr | Rate (95% CI) |

||

| no. | % | no. | % | ||||

| Linked transmission | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Total | 1 | 1585.3 | 0.1 (0.0–0.4) | 27 | 1567.3 | 1.7 (1.1–2.5) | 0.04 (0.01–0.27) |

|

| |||||||

| 1 yr | 1 | 819.0 | 0.1 (0.0–0.7) | 16 | 813.3 | 2.0 (1.1–3.2) | 0.06 (0.00–0.40) |

|

| |||||||

| 2–3 yr | 0 | 686.5 | 0.0 (0.0–0.5) | 9 | 682.8 | 1.3 (0.6–2.5) | 0.00 (0.00–0.50) |

|

| |||||||

| >3 yr | 0 | 79.9 | 0.0 (0.0–4.6) | 2 | 71.2 | 2.8 (0.3–10.1) | 0.00 (0.00–4.75) |

|

| |||||||

| Any transmission† | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Total | 4 | 1585.3 | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 35 | 1567.3 | 2.2 (1.6–3.1) | 0.11 (0.04–0.32) |

|

| |||||||

| 1 yr | 2 | 819.0 | 0.2 (0.0–0.9) | 18 | 813.3 | 2.2 (1.3–3.5) | 0.11 (0.01–0.46) |

|

| |||||||

| 2–3 yr | 2 | 686.5 | 0.3 (0.0–1.1) | 14 | 682.8 | 2.1 (1.1–3.4) | 0.14 (0.02–0.62) |

|

| |||||||

| >3 yr | 0 | 79.9 | 0.0 (0.0–4.6) | 3 | 71.2 | 4.2 (0.9–12.3) | 0.00 (0.00–2.16) |

|

| |||||||

| Clinical events‡ | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Total | 40 | 1661.9 | 2.4 (1.7–3.3) | 65 | 1641.8 | 4.0 (3.1–5.0) | 0.59 (0.40–0.88) |

|

| |||||||

| 1 yr | 29 | 831.0 | 3.5 (2.3–5.0) | 39 | 832.6 | 4.7 (3.3–6.4) | 0.75 (0.44–1.24) |

|

| |||||||

| 2–3 yr | 9 | 739.8 | 1.2 (0.6–2.3) | 21 | 725.7 | 2.9 (1.8–4.4) | 0.42 (0.17–0.96) |

|

| |||||||

| >3 yr | 2 | 91.1 | 2.2 (0.3–7.9) | 5 | 83.6 | 6.0 (1.9–14.0) | 0.37 (0.04–2.24) |

|

| |||||||

| Composite events§ | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Total | 23 | 1700.1 | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | 79 | 1642.0 | 4.8 (3.8–6.0) | 0.28 (0.18–0.45) |

|

| |||||||

| 1 yr | 13 | 843.7 | 1.5 (0.8–2.6) | 47 | 833.9 | 5.6 (4.1–7.5) | 0.27 (0.14–0.51) |

|

| |||||||

| 2–3 yr | 8 | 763.8 | 1.0 (0.5–2.1) | 26 | 732.5 | 3.5 (2.3–5.2) | 0.30 (0.12–0.67) |

|

| |||||||

| >3 yr | 2 | 92.6 | 2.2 (0.3–7.8) | 6 | 75.5 | 7.9 (2.9–17.3) | 0.27 (0.03–1.52) |

Hazard ratios were calculated with the use of unstratified univariate Cox regression analysis on an intention-to-treat basis. Year-specific rate ratios were calculated on the basis of the person-year analysis. P<0.001 for the between-group comparison for linked transmission, P<0.001 for all transmission, P = 0.01 for clinical events, and P<0.001 for composite events, with all comparisons favoring early therapy.

Any transmission includes all transmission events observed during follow-up, regardless of their linkage between partners.

Clinical events include death, World Health Organization stage 4 events, severe bacterial infections, and pulmonary tuberculosis for index partners.

Composite events include death or World Health Organization stage 4 events (excluding esophageal candidiasis) for the index partner or HIV transmission to the uninfected partner, whichever occurred earlier.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier Estimates for Partner-Linked and Any HIV-1 Transmission and for Clinical and Composite Monitoring Events.

Shown are Kaplan–Meier estimates for the cumulative probabilities of linked HIV-1 transmission between partners (Panel A), any HIV transmission (Panel B), clinical events (Panel C), and composite monitoring events (Panel D) among participants in the early-therapy and delayed-therapy groups.

The rate of transmission events in the delayed-therapy group was relatively constant across the first 3 years of study follow-up for both linked and any transmissions. Of the 28 HIV-1–infected participants who had linked transmission to a partner, 17 (61%) had a CD4 count of more than 350 cells per cubic millimeter at the study visit before the detection of linked HIV-1 transmission. The single linked transmission in the early-therapy group was identified 3 months after the HIV-1– infected participant initiated treatment; all linked transmissions in the delayed-therapy group occurred while the HIV-1–infected participant was not receiving antiretroviral therapy. The Kaplan– Meier curves for both linked and any transmissions show immediate and sustained reduction in the risk of HIV-1 transmission after the initiation of antiretroviral therapy (Fig. 2).

Of the 28 linked transmissions, 23 (82%) occurred at African sites. HIV-1–infected women were the source of infection in 18 of 27 (67%) linked transmissions in the delayed-therapy group, and a man was the source of the single transmission in the early-therapy group. Women were the HIV-1–infected participant in 58% of African couples. A high viral load in blood plasma of infected participants at baseline increased the risk of HIV-1 transmission (Table 3). The median plasma viral load in 27 participants at the visit most proximal to the detection of HIV-1 transmission was 4.9 log10 (range, 2.6 to 5.8). Conversely, self-reported 100% condom use at baseline was associated with a reduced risk of HIV-1 transmission. In the stratified multivariate analysis according to site, the adjusted hazard ratio for linked transmission in the early-therapy group was 0.04 (95% CI, 0.01 to 0.28; P<0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Hazard Ratios for Prognostic Factors for Partner-Linked and Any HIV-1 Transmission and for Clinical and Composite Events*.

| Variable | Linked Transmission | Any Transmission | Clinical Events | Composite Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| Univariate analysis | ||||

|

| ||||

| Early therapy vs. delayed therapy | 0.04 (0.01–0.26) | 0.11 (0.04–0.32) | 0.60 (0.41–0.90) | 0.28 (0.18–0.45) |

|

| ||||

| Baseline CD4 count (per 100 CD4 increment) | 1.27 (1.02–1.59) | 1.25 (1.02–1.52) | 0.84 (0.70–1.00) | 1.06 (0.91–1.24) |

|

| ||||

| Baseline viral load (per unit log10 increment) | 1.96 (1.17–3.27) | 1.66 (1.08–2.55) | 1.74 (1.32–2.30) | 1.51 (1.15–1.97) |

|

| ||||

| Male sex vs. female sex | 0.69 (0.31–1. 52) | 0.88 (0.45–1.71) | 1.61 (1.05–2.48) | 1.18 (0.78–1.78) |

|

| ||||

| Baseline condom use (100% vs. <100%) | 0.35 (0.14–0.88) | 0.47 (0.19–1.14) | NA | 0.68 (0.29–1.60) |

|

| ||||

| Multivariate analysis | ||||

|

| ||||

| Early therapy vs. delayed therapy | 0.04 (0.01–0.28) | 0.11 (0.04–0.33) | 0.59 (0.40–0.89) | 0.28 (0.18–0.45) |

|

| ||||

| Baseline CD4 count (per 100 CD4 increment) | 1.24 (1.00–1.54) | 1.22 (1.02–1.47) | 0.90 (0.75–1.08) | 1.11 (0.96–1.28) |

|

| ||||

| Baseline viral load (per unit log10 increment) | 2.85 (1.51–5.41) | 2.13 (1.30–3.50) | 1.65 (1.24–2.20) | 1.60 (1.21–2.11) |

|

| ||||

| Male sex vs. female sex | 0.73 (0.33–1.65) | 1.00 (0.51–1.97) | 1.46 (0.95–2.26) | 1.18 (0.78–1.80) |

|

| ||||

| Baseline condom use (100% vs. <100%) | 0.33 (0.12–0.91) | 0.41 (0.16–1.08) | NA | 0.64 (0.27–1.52) |

Hazard ratios were calculated with the use of univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis, stratified according to study site. The results are similar to those calculated with the use of unstratified Cox regression analysis, which are not shown. NA denotes not applicable.

Primary Treatment Outcome

A total of 105 treatment end points, as measured by the first serious HIV-1–related clinical event or death, were observed in HIV-1–infected participants: 40 in the early-therapy group and 65 in the delayed-therapy group (hazard ratio, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.88; P = 0.01 (Table 2, and the Supplementary Appendix). Of such clinical events, 44% occurred in Asia and 45% in Africa. The baseline plasma viral load was an important predictor of clinical events, as assessed on multivariate analysis (Table 3). In the stratified multivariate model, the adjusted hazard ratio for clinical events in the early-therapy group was 0.59 (95% CI, 0.40 to 0.89). The difference in the rate of clinical events appeared to be driven mainly by the incidence of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, which developed in 3 participants in the early-therapy group and 17 in the delayed-therapy group (P = 0.002); of these cases, 55% were observed in India. Pulmonary tuberculosis was observed in 13 participants in the early-therapy group and 15 in the delayed-therapy group; isoniazid prophylaxis was administered to only 4% of participants in each study group. There were 23 deaths during the course of the study, 10 in the early-therapy group and 13 in the delayed-therapy group (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.34 to 1.76; P = 0.27) (for details regarding causes of death, see the Supplementary Appendix).

Composite Monitoring Events

Among 102 composite monitoring events, there were 39 transmission events in which the sexual partner acquired HIV-1. Among HIV-1–infected participants, 21 died and 42 had WHO stage 4 clinical events. Of these monitoring events, 58 (57%) occurred in Africa, 31 (30%) in Asia, and 13 (13%) in the Americas. Overall, 23 monitoring events were observed in the early-therapy group and 79 in the delayed-therapy group (hazard ratio, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.45; P<0.001) (Table 2). According to the monitoring guidelines that were based on the Lan–DeMets implementation of O'Brien– Fleming boundaries, the computed z statistic was 4.43, which exceeded the prespecified cutoff of 3.93 and thus ruled out the hypothesis that early therapy would provide at most a 20% reduction in the risk of the composite monitoring end point.

Adverse Events

After the exclusion of primary clinical end points (death, WHO stage 4 events, pulmonary tuberculosis, and severe bacterial infections), 246 HIV-1– infected participants had one or more severe or life-threatening adverse events (grade 3 or 4): 127 of 886 (14%) were in the early-therapy group and 119 of 877 (14%) were in the delayed-therapy group (P = 0.64). The most frequently reported adverse events included infections, psychiatric and nervous system disorders, metabolism and nutrition disorders, and gastrointestinal disorders (for details, see the Supplementary Appendix). Grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormalities during study follow-up occurred in 242 participants (27%) in the early-therapy group and 161 participants (18%) in the delayed-therapy group (P<0.001). The most frequent laboratory abnormalities included neutropenia, abnormal phosphate level, and total bilirubin elevations (with bilirubin elevations observed primarily in participants taking atazanavir as part of their drug regimen) (see the Supplementary Appendix).

Discussion

In this study involving 1763 serodiscordant couples in which HIV-1–infected participants had a CD4 count of 350 to 550 cells per cubic millimeter, there was a relative reduction of 96% in the number of linked HIV-1 transmissions resulting from the early initiation of antiretroviral therapy, as compared with delayed therapy. There was a relative reduction of 89% in the total number of HIV-1 transmissions resulting from the early initiation of antiretroviral therapy, regardless of viral linkage with the infected partner. The sustained suppression of HIV-1 in genital secretions resulting from antiretroviral therapy is the most likely mechanism for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission that we observed.4,5

The majority of HIV-1 transmissions (82%) were observed in Africa. This result reflects not only the large number of study participants who were enrolled in this region (54%) but also other factors that increase the probability of HIV-1 transmission among African couples. Several groups have reported higher viral loads in patients with HIV-1 infection in sub-Saharan Africa than in patients in developed countries.22,23 Clade C HIV-1, the dominant type in southern Africa, may have other transmission advantages as well.24 More frequent sexual encounters and limited condom use would also favor increased HIV transmission among African couples, possibilities that are being evaluated.

Although HIV-1 transmission from patients with acute and early HIV-1 infection and advanced HIV-1 disease and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)25 appears to be most efficient,26 the results from this and other studies9 emphasize that HIV-1 can be transmitted from infected persons who are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic and who have high CD4 counts. Since most persons with established HIV-1 infection fall into the latter category, such transmission, albeit not maximally efficient, must help fuel the spread of HIV-1.

Early antiretroviral therapy was associated with a relative reduction of 41% in the number of HIV-1–related clinical events, which suggests a clinical benefit for the initiation of antiretroviral therapy when a person has a CD4 count of 350 to 550 cells per cubic millimeter, as compared with therapy that is delayed until the CD4 count falls into the range of 200 to 250 cells per cubic millimeter. In contrast to a recent trial15 comparing the effect of the initiation of therapy in patients with a CD4 count ranging from 200 to 350 cells per cubic millimeter with those with a count below 200 cells per cubic millimeter, we did not detect a significant between-group difference in overall mortality. Despite our relatively short follow-up period, the magnitude of the clinical effect we observed was similar to that seen in observational studies conducted in the developed world.16-18 The difference between the early-therapy group and the delayed-therapy group was driven largely by the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, with the majority of these cases occurring in India. The use of isoniazid prophylaxis, although recommended by the WHO for patients with HIV-1 infection,27 was infrequently prescribed for participants in this study. In addition, data from observational studies focusing on HIV-1–related and non–HIV-1–related clinical events and CD4 counts have led to the hypothesis that delayed antiretroviral therapy could ultimately lead to an increased rate of clinical events, regardless of subsequent therapy.28 However, we cannot evaluate this possibility without a longer period of follow-up.

We noted more adverse events in the early-therapy group than in the delayed-therapy group, including more adverse events related to antiretroviral therapy. The clinical importance of the laboratory abnormalities that were responsible for this difference is unclear. Further examination of these data and additional longitudinal follow-up will be important to better understand the clinical and public health benefits of early antiretroviral therapy, as compared with drug costs and side effects.

Our study has several limitations. In order to examine the effects of antiretroviral therapy on HIV-1 transmission, we studied stable HIV-1–discordant couples, who may not be entirely representative of the general population.29 We provided ongoing couples counseling and condoms, which probably contributed to the low incidence of HIV-1 infection, as previously reported.30 Some participants received trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and isoniazid prophylaxis at the discretion of the investigators, which could have reduced the degree of benefit observed with early antiretroviral therapy.31

In conclusion, the biologic plausibility of the use of antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 infection has been carefully examined during the past two decades.32 The idea of HIV-1 treatment as prevention has garnered tremendous interest and hope33 and inspired a series of population-level HIV-1 treatment-as-prevention studies that are now in the pilot or planning stages.34,35 Such interventions are based on the hypothesis that the use of antiretroviral therapy reliably prevents HIV-1 transmission over an extended period of time. In this trial, we found that early antiretroviral therapy had a clinical benefit for both HIV-1–infected persons and their uninfected sexual partners. These results support the use of antiretroviral treatment as a part of a public health strategy to reduce the spread of HIV-1 infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) and by grants (UM1-AI068619 and U01-AI068619; UM1-AI068613 and U01-AI068613, to the HPTN Network Laboratory; and UM1-AI068617 and U01-AI068617, to the HPTN Statistical and Data Management Center) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Study drugs were donated by Abbott Laboratories, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline/ViiV Healthcare, and Merck.

Dr. Hosseinipour reports receiving lecture fees from Abbott Virology; Dr. Eshleman, consulting fees from Roche Diagnostics, lecture fees and samples or laboratory reagents from Abbott Diagnostics and Celera Diagnostics, and lecture fees from Monogram Biosciences; Dr. Mills, grant support from GlaxoSmithKline; Dr. de Bruyn, travel support from Sanofi Pasteur; Dr. Eron, consulting fees and grant support from Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and ViiV Healthcare, consulting fees from Gilead Sciences and Tibotec, and lecture fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Roche; Dr. Gallant, consulting fees from Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Tibotec Therapeutics, ViiV Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Sangamo BioSciences, and Koronis, grant support and travel support from Gilead Sciences, and lecture fees from Monogram Biosciences; Dr. Havlir, study drug from Abbott; and Dr. Swindells, consulting fees from Gilead Sciences and Abbott Diagnostics and grant support from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

We thank Drs. Wafaa El-Sadr, Quarraisha Abdool Karim, and Ward Cates for their help in the preparation of the manuscript.

Funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and others; HPTN 052 ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00074581.

Appendix

The authors' affiliations are as follows: the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill (M.S.C., M.C.H., I.F.H., J.E.); the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Y.Q.C., L.W.), and the University of Washington (T.R.F.) — both in Seattle; Family Health International, Arlington, VA (M.M.), and Durham, NC (T.G.); the UNC Project, Lilongwe (M.C.H.) and the College of Medicine–Johns Hopkins Project, Blantyre (J.K.) — both in Malawi; the Y.R. Gaitonade Center for AIDS Research and Education, Chennai (N.K.), and the National AIDS Research Institute, Pune (S.M., S.V.G.) — both in India; University of Zimbabwe, Harare (J.G.H.); Instituto de Pesquisa Clinica Evandro Chagas, Fiocruz (B.G.), and Hospital Geral de Nova Iguacu and Laboratorio de AIDS e Imunologia Molecular-IOC/Fiocruz (J.H.S.P.) — both in Rio de Janeiro; Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand (S.C.); Hospital Nossa Senhora da Conceição, Porto Alegre, Brazil (B.R.S.); Fenway Health (K.H.M.) and Harvard School of Public Health (H.R., M.E.) — both in Boston; Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (S.H.E., E.P.-M., J.G.) and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (T.E.T., D.C.) — both in Baltimore; Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute, Gaborone (J.M.); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Kenya Medical Research Institute–CDC Research and Public Health Collaboration HIV Research Branch, Kisumu (L.A.M.); Perinatal HIV Research Unit (G.B.) and Department of Medicine (I.S.), University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg; University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco (D.H.); University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha (S.S.); Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (V.E., D.B.); and David Geffen UCLA School of Medicine, Los Angeles (K.N.-S.).

Footnotes

The authors' affiliations are listed in the Appendix.

Other members of the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 052 Study Team are listed in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org.

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Ray M, Logan R, Sterne JA, et al. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24:123–37. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283324283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367:817–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. Erratum, Lancet 2006;367:1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MS, Gay CL. Treatment to prevent transmission of HIV-1. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50 3:S85–S95. doi: 10.1086/651478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham SM, Holte SE, Peshu NM, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy leads to a rapid decline in cervical and vaginal HIV-1 shedding. AIDS. 2007;21:501–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801424bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vernazza PL, Troiani L, Flepp MJ, et al. Potent antiretroviral treatment of HIV infection results in suppression of the seminal shedding of HIV. AIDS. 2000;14:117–21. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001280-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baeten JM, Kahle E, Lingappa JR, et al. Genital HIV-1 RNA predicts risk of heterosexual HIV-1 transmission. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:77ra29. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Solberg P, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2006;20:85–92. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196566.40702.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2092–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del Romero J, Castilla J, Hernando V, Rodriguez C, Garcia S. Combined antiretroviral treatment and heterosexual transmission of HIV-1: cross sectional and prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reynolds SJ, Makumbi F, Nakigozi G, et al. HIV-1 transmission among HIV-1 discordant couples before and after the introduction of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2011;25:473–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283437c2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373:48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das M, Chu PL, Santos GM, et al. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montaner JS, Lima VD, Barrios R, et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376:532–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60936-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Severe P, Juste MA, Ambroise A, et al. Early versus standard antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected adults in Haiti. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:257–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1815–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterne JA, May M, Costagliola D, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-free HIV-1-infected patients: a collaborative analysis of 18 HIV cohort studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1352–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60612-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cain LE, Logan R, Robins JM, et al. When to initiate combined antiretroviral therapy to reduce mortality and AIDS-defining illness in HIV-infected persons in developed countries: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:509–15. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-154-8-201104190-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eshleman SH, Hudelson SE, Redd AD, et al. Analysis of genetic linkage of HIV from couples enrolled in the HIV Prevention Trials Network 052 trial. J Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir651. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeMets DL, Lan KK. Interim analysis: the alpha spending function approach. Stat Med. 1994;13:1341–52. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics. 1979;35:549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dyer JR, Kazembe P, Vernazza PL, et al. High levels of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in blood and semen of seropositive men in sub-Saharan Africa. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1742–6. doi: 10.1086/517436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novitsky V, Ndung'u T, Wang R, et al. Extended high viremics: a substantial fraction of individuals maintain high plasma viral RNA levels after acute HIV-1 subtype C infection. AIDS. 2011 April 18; doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283471eb2. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ping LH, Nelson J, Hoffman I, et al. Characterization of V3 sequence heterogeneity in subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from Malawi: underrepresentation of X4 variants. J Virol. 1999;73:6271–81. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6271-6281.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1403–9. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powers KA, Poole C, Pettifor AE, Cohen MS. Rethinking the heterosexual infectivity of HIV-1: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:553–63. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70156-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource constrained settings. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241500708_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker JV, Peng G, Rapkin J, et al. CD4+ count and risk of non-AIDS diseases following initial treatment for HIV infection. AIDS. 2008;22:841–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f7cb76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eyawo O, de Walque D, Ford N, Gakii G, Lester RT, Mills EJ. HIV status in discordant couples in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:770–7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Celum C, Wald A, Lingappa JR, et al. Acyclovir and transmission of HIV-1 from persons infected with HIV-1 and HSV-2. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:427–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowrance D, Makombe S, Harries A, et al. Lower early mortality rates among patients receiving antiretroviral treatment at clinics offering cotrimoxazole prophylaxis in Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen MS, Gay C, Kashuba AD, Blower S, Paxton L. Narrative review: antiretroviral therapy to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV-1. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:591–601. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. JAMA. 2009;301:2380–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burns DN, Dieffenbach CW, Vermund SH. Rethinking prevention of HIV type 1 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:725–31. doi: 10.1086/655889. Erratum, Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith K, Powers KA, Kashuba AD, Cohen MS. HIV-1 treatment as prevention: the good, the bad, and the challenges. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:315–25. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32834788e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.