State of Health Care in the US

Many feel that the impending acceleration of global warming is the greatest threat that our species has ever faced. Less arguable but already having an impact is a drastic climate change in health care. Not only is it shaking up health care delivery and insurance, but its effects are visible on the education, training, certification, and accreditation systems of physicians and other health care professionals and organizations throughout the US.

The US public is increasingly questioning medical care. Well-publicized cases of poor quality of care, wide variations in practice, embarrassing failures to achieve good patient outcomes (such as routine preventive care, hypertension control, management of chronic disease, and prevention of postsurgical infections),1 escalating health care costs,2 and interactions between physicians and commercial entities3 have led to increasing public outcry and legislative scrutiny.

It seems as if Mother Nature's vengeance is palpable already.

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine described US health care in crisis, with 30–40% of patients not getting evidence-based care and with 25% of the care delivered not needed or actually harmful to patients.4 Evidence demonstrates overuse, underuse, and misuse, even in situations with appropriate access to care.5–7

A whole alphabet soup of health care-related organizations and groups has been trying to develop better methods of oversight in their areas of control.

Fortunately, all those groups are also now aligning around the common goal of improving patient care and protecting the public through a focus on performance assessment and improvement. They are creating systems that actually support each other rather than generate differing and sometimes bewildering requirements.

Realistically, physicians are only one part of the problem, and that means that we're only one part of the solution. The systems and environments in which we practice, access to care, other health care professionals, and patients themselves play significant roles, too. But the challenge for us as physicians is to see how our role is changing and how the “be all and end all” is “Quality” of care (with a capital Q).

There are many factors driving up the Quality of care, and these include respected quality constructs (such as, Plan-Do-Study-Act and Six Sigma),8 electronic health records (such as, Kaiser Permanente HealthConnect), clinical decision support systems, public reporting, and pay for performance. There is also a relatively new construct called Continuous Professional Development. Think of it as Continuing Medical Education (CME) Version 2.0.

New Face of Continuing Medical Education

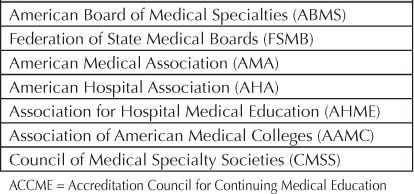

Similar to how The Joint Commission sets hospital standards for accreditation, requirements in the US regarding CME are directed by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). The ACCME is a national organization formed through and accountable to the joint membership of seven other key national organizations 9 (Table 1). Directly or indirectly, the ACCME accredits organizations that offer CME activities for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit. Whereas the credit system was developed and is maintained by the American Medical Association (AMA),10 the ACCME identifies, develops, and promotes standards for accredited CME providers nationwide who in turn offer CME activities to physicians.11 Just as medicine evolves over time, so have these standards.

Table 1.

ACCME member organizations

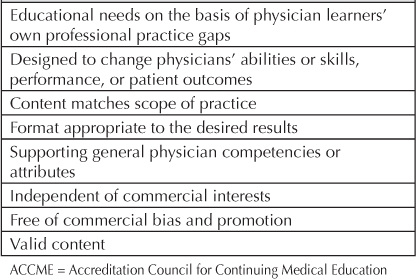

The most recent CME standards, released in September 2006, explicitly require that CME activities support improvements in the Quality of care. Key components of the 2006 Accreditation Criteria require that CME activities relate to the actual scope of practice of physicians, narrow the differences between current practice and best practice, use formats that will meet the desired results, use evidence-based content, and are independent from commercial influence.12 Acceptable outcome measurements for CME activities focus on changes in physicians' skills or abilities, actual performance on the job, or patient outcomes (Table 2).

Table 2.

ACCME accreditation criteria for Continuing Medical Education activities (partial list)

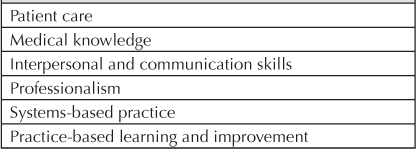

The necessary skill set of physicians includes more than just clinical knowledge. Therefore, the content of CME must also address more than merely knowledge and include communication, working in teams and systems, use of information technology, patient-centered care, professionalism, commitment to lifelong learning and quality improvement, among other key attributes identified from health care organizations and professional societies. These competencies largely derive from those defined by the Institute of Medicine, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and the American Board of Medical Specialties.13 Essentially all these organizations are coming to closer agreement on what defines a quality and qualified practicing physician (Table 3).

Table 3.

American Board of Medical Specialties core physician competencies (attributes)

Conventional CME has often been stand-alone lectures to large, diverse audiences featuring experts of national reputation flown in from far away delivering essentially canned presentations. New and improved models of CME are emerging to meet the different needs and learning styles of today's physicians and health care system. CME is increasingly taking on new forms. Some examples of this include “just-in-time learning” in the work setting or online (eg, Internet Point of Care CME activities, Committee Learning CME Activities); problem-based, team and systems learning and change (eg, Performance Improvement CME Activities); and multi-interventional, experiential, and/or self-assessed curricula around particularly complex areas of practice.

How effective CME is at improving patient care is a longstanding question that still cannot be accurately answered. The limited evidence to date (almost exclusively based on conventional lecture formats) does show that CME can be effective in changing physician knowledge and performance.14,15 But not all CME is created equal.

Compared to older standards, the 2006 CME criteria help ensure that CME activities are not only more effective, but also more strategically important to physicians, health-related organizations and the public (ie, our patients).16 CME is no longer only about “getting credit.” Today's CME is a means to an end—not the end in itself.

At its best, CME is a change agent. And a powerful one at that—partly because its credits are still of value to physicians and other health care professionals.

You're probably now wondering what happened to the idea that CME is something that I need to do to maintain my medical license and prepare for my Board recertification. Why is CME so “difficult” now when that's really all I want from it?

New Face of Board Recertification and License Renewal

The answer lies in the fact that maintaining Board certification and a medical license is no longer an episodic event every so many years. Like CME, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) (who set the direction for Board certification and medical licensure, respectively) are putting a new face on these processes, and in doing so they are taking a different view of CME and CME credits. They aren't far along in making the changes, but the winds have definitely shifted.

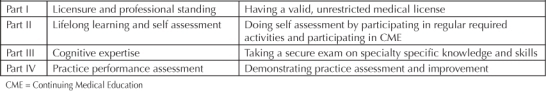

Maintenance of Certification (MOC) is a relatively new approach to Board certification. The ABMS, which is the umbrella organization governing all 24 recognized specialty Boards, has implemented a universal policy of time-limited certificates (no more lifetime certification!) and a process for maintenance of certification (ie, continuous process), rather than recertification (ie, one-time process). The biggest change is that instead of just having to get a certain number of CME credits and pass a test every 7–10 years, now there are additional requirements.17 The ABMS and all their Member Boards have agreed to an expanded 4-part MOC process (Table 4).

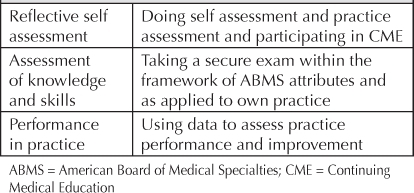

Table 4.

Maintenance of Certification

… practicing physicians will need to participate in an ongoing process of continuous professional development and assessment …

Yes, there is still an exam to take and CME activities to do, but there is more. Each of these four components is required for all Boards, though each Board gets to set its own process for how MOC will be implemented, and some are further along in this process than others. ABMS and the individual Boards might be prescriptive in terms of which CME activities will count, requiring that they be relevant to your specialty and perhaps even considering the role of commercial support and the relationships that the individuals involved have with commercial interests.

The Permanente Federation and the various Permanente Medical Groups are working together and with the ABMS and its Member Boards to support Permanente physicians in this process.18,19 Most notably, the National (Permanente Federation) and Regional CME offices are in various stages of gaining approval for physicians to use organizational quality-improvement projects in which they are already participating as their Part IV MOC. Board-approved Part II MOC activities are also being developed and offered within the organization. These efforts should drastically reduce the cost, time, and hassle otherwise typically encountered by individual physicians and outside practices struggling to meet MOC.

Maintenance of Licensure (MOL) is governed by the FSMB. The goal is to protect the public by licensing physicians who can demonstrate that they provide good care. Unfortunately, this has been difficult to assess in the absence of litigation or criminal proceedings. CME has been used as a “surrogate” marker for “competence” by many states that require it for licensure. However, as long ago as 2002, the FSMB realized that CME credit alone may be unrelated to a physicians' competence or actual practice. Even so, they have struggled to find other ways to assess physicians.

In late 2010, the FSMB released a recommendation for all state licensing boards to adopt requirements similar to those required for MOC,20 including participating in CME, a proctored exam, and performance improvement (Table 5). They also recommended that this be a 5-year cycle, and that all 70 state licensing medical and osteopathic boards adopt this within 10 years. Although this is voluntary, some states have already started implementing the requirements, and as more states adopt this policy, it will create momentum for all states to adopt. The California Board of Osteopathic Medicine has already started implementing these requirements; however, the Medical Board of California has not. Presumably, if your state has adopted these standards, they have or will notify you, but you can also check with them directly as this is a moving target.

Table 5.

Maintenance of Licensure

For those physicians who are either “grandfathered in” to specialty Board certification or do not wish or need to maintain their Board certification, the MOL requirements will likely catch up with them because they still need to maintain their medical license.

So either way you cut it, practicing physicians will need to participate in an ongoing process of continuous professional development and assessment, exemplified by MOC and/or MOL. And—if all goes according to plan—the similarities between the two systems are going to be many, and the role of CME is going to be critical.

Alignment between Continuing Medical Education, Maintenance of Certification, and Maintenance of Licensure

Recognizing that CME activities that are unrelated to a physician's actual practice does not support the vision for MOC, the ABMS has implemented a policy that only CME related to the physician's own practice can be used to meet the CME requirements for MOC. The FSMB has endorsed a similar principle for MOL. Luckily, because CME standards now require that activities be directed at the actual or desired scope of practice, it is much easier to demonstrate this if CME activities are chosen deliberately.

It is a fundamental truth that all physicians strive to provide great care.

A goal to be mediocre does not lead to success in medical school or residency. CME is changing to provide information and tools to help physicians provide that great care. With medical information changing so rapidly and the delivery of care changing (use of technology, informatics, team based care, etc), it is difficult for physicians to keep up with advances in their own fields.

Learning about other specialties might support a more “well-rounded” physician and be of interest to some physicians; however, given the limitation of time and monetary resources for CME, the questions are: Is it better spent on topics that are of interest but limited practical use, or instead spent on CME that will help support that great care we all want to provide? If Board certification denotes competence in that specialty and medical licensure denotes being a qualified physician, then shouldn't CME that is used to support certification and licensure be related to what we actually do within the specific scope of our practice or job?

As primary care physicians, for example, the authors may be interested in the technique of hip replacement surgery, but for our practice—and our patients—what we really need to know is how to evaluate hip pain, how to manage it and prevent it getting worse, and how to know when to refer to an orthopedist about potential replacement or other interventions. Even physicians eventually become patients. So, as patients, if we ever end up on an operating table for that hip replacement (and we hope we don't), we would want our surgeons to use their CME resources to learn about how to improve surgical and postsurgical outcomes, rather than about the latest controversy on breast cancer screening or the history of medicine in the 20th century.

Continuous Professional Development

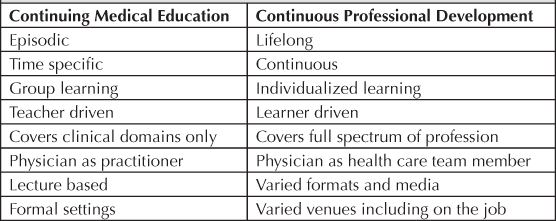

Continuous Professional Development is the latest buzz.21 As we mentioned, some say it is CME Version 2.0 (Table 6). Whether or not you subscribe to that, continuous professional development and assessment are the basis of new faces of CME, MOC, and MOL.

Table 6.

Comparison of attributes of Continuing Medical Education and Continuous Professional Development

In today's world and going forward, physicians have more and more choices for CME opportunities, and accredited organizations that provide CME are responsible, under current CME standards, for creating activities that actually make a difference in practice.

When physicians expect and select CME activities to specifically help their practices (with content related to scope of practice, addressing actual care gaps, with tools and strategies to be able to apply the information based on the best and unbiased evidence), the entire health care system in the US will reap the benefits. Physicians will be poised for success in MOC and MOL, and patients will experience improved Quality of care (remember, with a capital “Q”).

We should demand nothing less!

And who knows? We might just come out of this climate change and realize that we have actually supported our fundamental desire as physicians to provide great care.

References

- 2010 National Healthcare Quality Report: AHRQ Publication No. 11-0004 [monograph on the Internet] Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011 Mar. (cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhqr10/nhqr10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbuende E, Ranji U, Lundy J, Salganicoff A. US Health Care Costs [monograph on the Internet] Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010 Mar. [cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: www.kaiseredu.org/Issue-Modules/US-Health-Care-Costs/Background-Brief.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Hager M, Russell S, Fletcher SW, editors. New York: Josiah Macy, Jr Foundation; 2008. Continuing education in the health professions: improving healthcare through lifelong learning. Proceedings of a conference sponsored by the Josiah Macy, Jr Foundation; 2007 Nov 28–Dec 1; Bermuda [monograph on the Internet] [cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: www.josiahmacyfoundation.org/docs/macy_pubs/pub_ContEd_inHealthProf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jun 26;348(26):2635–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangione-Smith R, DeCristofaro AH, Setodji CM, et al. The quality of ambulatory care delivered to children in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007 Oct 11;357(15):1515–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospital compare [Web page on the Internet] Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; updated 2011 Apr 11 [cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Varkey P, Reller MK, Resar RK. Basics of quality improvement in health care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007 Jun;82(6):735–9. doi: 10.4065/82.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- About us: Board of Directors [Web page on the Internet] Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education; 2011. [cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: www.accme.org/index.cfm/fa/about.directors.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- The Physician's Recognition Award and credit system: Information for accredited providers and physicians [monograph on the Internet] Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2010. [cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/cme/pra-booklet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- About us [Web page on the Internet] Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education; 2011. [cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: www.accme.org/index.cfm/fa/about.home/About.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- The ACCME's essential areas and their elements [monograph on the Internet] Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education; 2006. [cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: www.accme.org/dir_docs/doc_upload/f4ee5075-9574-4231-8876-5e21723c0c82_uploaddocument.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- ACCME Standards for Commercial Support: Standards to ensure the independence of CME activities [monograph on the Internet] Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education; 2006 Mar. [cited 2011 Jul 24]. p 123. Available from: www.accme.org/dir_docs/doc_upload/97976287-85d0-4d5a-b2d3-a11df26949b8_uploaddocument.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Marinopoulos SS, Dorman T, Ratanawongsa N, et al. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007 Jan. Effectiveness of Continuing Medical Education. Evidence report/technology assessment No. 149 (Prepared by the Johns Hopkins Evidence-based Practice Center, under Contract No. 290-02-0018. AHRQ Publication No. 07-E006.) [Google Scholar]

- Moores LK, Dellert E, Baumann MH, Rosen MJ, American College of Chest Physician Health & Science Policy Committee Executive summary: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Educational Guidelines. Chest. 2009 Mar;135(3 Suppl):1S–4S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CME as a bridge to quality: Leadership, learning, and change within the ACCME System [monograph on the Internet] Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education; 2008 Jan. [cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: www.accme.org/dir_docs/doc_upload/51395e82-e13d-4d72-a72f-a311d84608ee_uploaddocument.htm. [Google Scholar]

- ABMS Maintenance of Certification [Web page on the Internet] Chicago, IL: American Board of Medical Specialties; 2006–2011. [cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: www.abms.org/Maintenance_of_Certification/ABMS_MOC.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Pasadena, CA: Kaiser Permanente, Physician Education; 2011 Jul. www.kpsymposia.com [homepage on the Internet] [cited 2011 Jul 24. Available from: www.kpsymposia.com. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Permanente: TPMG Physician Education & Development: Maintenance of Certification [Web page on the Internet] Oakland, CA: The Permanente Medical Group; 2011. [cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: http://insidekp.kp.org/ncal/tpmgphysicianed/moc/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Maintenance of Licensure (MOL) information center [Web page on the Internet] Euless, TX: Federation of State Medical Boards; 2010. [cited 2011 Jul 24]. Available from: www.fsmb.org/mol.html. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva AK. The new paradigm of continuing education in surgery. Arch Surg. 2005 Mar;140(3):264–69. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]