Abstract

Background: The purpose of this study is to evaluate the risk factors and the prevalence of thromboembolic events (TEEs) in breast cancer patients.

Patients and methods: This is a retrospective cohort study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare database. Breast cancer patients diagnosed from 1992 to 2005 ≥66 years old were identified. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes were used to identify TEEs within 1 year of the breast cancer diagnosis. Analyses were conducted using descriptive statistics and logistic regression.

Results: A total of 89 841 patients were included, of them 2658 (2.96%) developed a TEE. In the multivariable analysis, males had higher risk of a TEE than women [odd ratio (OR) = 1.57; confidence interval (CI) 1.10–2.25] and blacks had higher risk than whites (OR = 1.20; CI 1.04–1.40). Compared with stage I patients, patients with stage II, III and IV had 22%, 39% and 98% increase, respectively, in risk. Placement of central catheters (OR = 2.71; CI 2.43–3.02), chemotherapy treatment (OR = 1.66; CI 1.48–1.86) or treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) (OR = 1.33; CI 1.33–1.52) increase the risk. Other significant predictors included comorbidities, age, receptor status, marital status and year of diagnosis. Similar estimates were seen for pulmonary embolism, deep vein thromboembolism and other TEEs.

Conclusions: In total, 2.96% of patients in this cohort developed a TEE within 1 year from breast cancer diagnosis. Stage, gender, race, use of chemotherapy and ESAs, comorbidities, receptor status and catheter placement were associated with the development of TEEs.

Keywords: breast cancer, cancer-associated thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis, population-based study, thromboembolic events, thrombosis

introduction

Thromboembolic events (TEEs) are a common complication and a life-threatening condition in cancer patients [1, 2]. Trousseau [3] described in 1868 the relationship between malignancy and venous thrombosis. Today, it is well recognized that thrombosis and cancer are linked by multiple pathophysiological mechanisms and that tumor biology and coagulation processes are integrally connected [4].

Population-based studies have showed that the presence of cancer increases the risk of TEEs by four- and sevenfold [2, 5]. Furthermore, advanced age, race, stage, comorbidities and the use of systemic therapies and intravascular catheters are factors that have been associated with an increased risk of TEE in patients with cancer [1, 5–11]. Different risk estimates have been observed among different primary cancer sites; for example gastric, pancreatic, kidney cancers and astrocytomas are associated with a higher risk of developing a TEE than other cancers [1, 6].

Breast cancer patients are considered to be at relatively low risk of developing a TEE; a recent study reported an incidence rate of 1.2% within 2 years of diagnosis [12]. Data from clinical trials suggest that the risk is higher in patients receiving chemotherapy (2.1%) [13] or in those with metastatic disease (4.4%) [14]. Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in the United States[15]; therefore, the occurrence of a TEE represents a common clinical problem in patients with breast cancer. In this retrospective study, we sought to explore the incidence and the risk factors associated with TEEs in a large cohort of older patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer.

patients and methods

data source

We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked database. The SEER program, supported by the USA National Cancer Institute (NCI), collects data from tumor registries; during the years included in this study, the database covered 14%–25% of the USA population. The Medicare program is administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and covers 97% of the USA population aged ≥65 years [16]. Of SEER participants who were diagnosed with cancer at age ≥65 years, 94% are matched with their Medicare enrollment records [16].

Patient demographics, tumor characteristics, and treatment information were extracted from the SEER-Medicare Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary File (PEDSF); Medicare claims files for durable medical equipment (DME), physician/supplier [National Claims History (NCH)], inpatient service [Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR)], and outpatient service files.

study population

This study included patients ≥66 years old with a diagnosis of stage I–IV breast cancer (American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging third edition). Patients were required to have Medicare Part A and B and not to be members of a Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) for 1 year prior and after their breast cancer diagnosis, because Medicare claims are not complete for HMO members. From the initial 319 395 patients with breast cancer diagnosed from 1992 to 2005, 32 256 had history of prior or subsequent malignancies; 1 089 had an unknown month of diagnosis; 103 599 were <66 years old; 37 389 were unstaged or had an unknown initial stage; 45 511 did not have full coverage of Medicare A and B or were members of an HMO, and 193 had non-carcinoma histology. From them, only the 90 153 patients who developed a TEE within the first year of diagnosis and those not developing a TEE were included. Three hundred and twelve patients with an unknown education level were excluded, in order to preserve confidentiality and maintain at least 15 patients per cell in subgroup analyses, per NCI regulations. A total of 89 841 patients were included.

data extraction and definitions

The main outcome of this study was a TEE within the first year of breast cancer diagnosis. TEEs were defined as pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thromboembolism (DVT), or other/unclassified TEEs. To identify TEE cases, the study period for each patient was from 1 year before breast cancer diagnosis to 1 year after breast cancer was diagnosed or death (if within 1 year from breast cancer diagnosis). We identified cases of TEEs using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes from the Medicare claims files DME, NCH, MEDPAR, and outpatient service files. Diagnosis code 415.1x was identified as PE; codes 451, 453.1, 453.2, and 453.4 were identified as DVT; and codes 452, 453, 453.0, 453.3, 453.5, 453.6, 453.7, 453.8, and 453.9 were identified as other/unclassified TEEs. In the MEDPAR files, a patient was identified as having a TEE if there was a claim of PE, DVT, or other TEEs as primary diagnosis. In the other three claims files, a patient was classified as having a TEE if the diagnosis appeared in at least two claims with 30 days apart. After we identified the TEE cases, we merged them and chose the earliest date as the TEE diagnosis date.

Demographic and tumor characteristics were obtained from the PEDSF. For the census tract variables of education and poverty level, quartiles were calculated in increasing order. Chemotherapy was identified from Medicare claims; surgery and radiation therapy were identified from the SEER dataset and Medicare claims. Central venous catheter (CVC) placement in the first year after cancer diagnosis was identified from Medicare claims files DME, MEDPAR, NCH, and outpatient service files. Also the use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) in the same time period was recorded. Using ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes, the presence of comorbid conditions from 12 to 1 month before the diagnosis of breast cancer was identified in the Medicare inpatient, outpatient and physicians claims data. A comorbidity score was calculated using Klabunde's adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity index from the SAS macro provided by NCI [12,17–19]. The comorbidities included in the score are myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, diabetes (with and without end-organ damage), chronic pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, ulcer disease, liver disease, renal disease, hemiplegia, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was used. Chi-square tests were used to compare the frequency of demographic and tumor characteristics between patients who experienced at least one TEE and those who did not. Logistic regression was used to identify risk factors associated with the development of TEE within 1 year of breast cancer diagnosis. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. The variables entered in the multivariable logistic regression model included age, gender, race, marital status, education level, poverty level, geographical location, year of diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status, comorbidities (Charlson index), surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, presence of a CVC and the use of ESAs. All computer programming and statistical analyses were carried out with the SAS system (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and all tests were two sided.

results

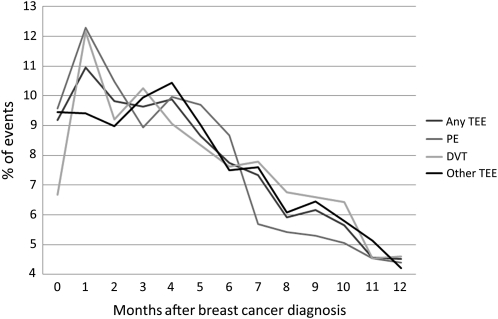

Our final cohort included 89 841 patients; the median age was 75.8 years. The stage distribution was 52.1%, 34.1%, 7.5% and 6.3% for stages I–IV, respectively. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 2658 (2.96%) patients developed at least one TEE within the first year of breast cancer diagnosis. Among the total study samples, 773 (0.86%) had a PE; 1259 (1.4%) had a DVT; and 1829 (2.04%) had other/unclassified TEEs. Some patients had more than one event; the total number of observed events was 3861. Among the patients who experienced an event, 1646 (62%) had only one type, 821 (31%) had two types, and 191 (7%) had three types of TEE. The majority of the events occurred during the first 3 months after breast cancer diagnosis (39.5%). A total of 26.5% of the events were diagnosed between the third and the sixth month and 34% of the events were seen from months 6 to 12 after diagnosis (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study cohort

| Frequency | % | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 66–70 | 22 289 | 24.81 |

| 71–75 | 22 989 | 25.59 |

| 76–80 | 20 630 | 22.96 |

| >80 | 23 933 | 26.64 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 89 172 | 99.26 |

| Male | 669 | 0.74 |

| Race | ||

| White | 77 776 | 86.57 |

| Black | 5646 | 6.28 |

| Other | 6419 | 7.14 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| 1992 | 4756 | 5.29 |

| 1993 | 4439 | 4.94 |

| 1994 | 4283 | 4.77 |

| 1995 | 4359 | 4.85 |

| 1996 | 4306 | 4.79 |

| 1997 | 4371 | 4.87 |

| 1998 | 4308 | 4.80 |

| 1999 | 4452 | 4.96 |

| 2000 | 8833 | 9.83 |

| 2001 | 9186 | 10.22 |

| 2002 | 9236 | 10.28 |

| 2003 | 9211 | 10.25 |

| 2004 | 9036 | 10.06 |

| 2005 | 9065 | 10.09 |

| Stage | ||

| I | 46 831 | 52.13 |

| II | 30 652 | 34.12 |

| III | 6710 | 7.47 |

| IV | 5648 | 6.29 |

| Estrogen receptor | ||

| Positive | 61 660 | 68.63 |

| Negative | 12 108 | 13.48 |

| Unknown | 16 073 | 17.89 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||

| 0 | 69 349 | 77.19 |

| 1 | 14 516 | 16.16 |

| 2+ | 5976 | 6.65 |

| Surgery | ||

| Breast conserving | 42 518 | 47.33 |

| Mastectomy | 42 773 | 47.61 |

| No surgery/unknown | 4550 | 5.06 |

| Radiation therapy | ||

| No | 45 405 | 50.54 |

| Yes | 43 123 | 48.0 |

| Unknown | 1313 | 1.46 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| No | 71 279 | 79.34 |

| Yes | 18 562 | 20.66 |

| CVC placement | ||

| No | 80 425 | 89.52 |

| Yes | 9416 | 10.48 |

| ESAs use | ||

| No | 83 596 | 93.05 |

| Yes | 6245 | 6.95 |

CVC, central venous catheter; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent.

Figure 1.

Time of TEE after breast cancer diagnosis. TEE, thromboembolic event; PE, pulmonary embolism; DVT, deep vein thromboembolism.

We observed that men with breast cancer were more likely to develop a TEE than women (5.08% versus 2.94%). Black patients had TEEs more frequently than whites or other races (4.96% versus 2.89% versus 2.01%, respectively). Stage had a clear association with the development of TEE with higher rates seen in more advanced stages (1.87% for stage I, 3.3% for stage II, 5.02% for stage III and 7.63% for stage IV). Increased comorbidities as well as the use of chemotherapy (6.09%), CVC placement (9.23%) and the use of ESAs (7.7%) were all associated with a higher event frequency. Similar results were seen when PEs, DVTs and other TEEs were analyzed separately. The frequency of the distribution of risk factors is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of demographic characteristics and risk factors according to TEE

| Any TEE |

PE |

DVT |

Other TEEs |

|||||||||||||

|

N = 89 841 |

Cases = 2658 |

N = 87 956 |

Cases = 773 |

N = 88 442 |

Cases = 1259 |

N = 89 012 |

Case = 1829 |

|||||||||

| Total | Nocases | % | P | Total | Nocases | % | P | Total | Nocases | % | P | Total | Nocases | % | P | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||||||

| 66–70 | 22 289 | 676 | 3.03 | 0.172 | 21 802 | 189 | 0.87 | 0.659 | 21 950 | 337 | 1.54 | 0.081 | 22 073 | 460 | 2.08 | 0.119 |

| 71–75 | 22 989 | 715 | 3.11 | 22 482 | 208 | 0.93 | 22 616 | 342 | 1.51 | 22 776 | 502 | 2.2 | ||||

| 76–80 | 20 630 | 601 | 2.91 | 20 212 | 183 | 0.91 | 20 304 | 275 | 1.35 | 20 448 | 419 | 2.05 | ||||

| >80 | 23 933 | 666 | 2.78 | 23 460 | 193 | 0.82 | 23 572 | 305 | 1.29 | 23 715 | 448 | 1.89 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||

| Female | 89 172 | 2624 | 2.94 | 0.001 | 87 308 | 760 | 0.87 | 0.002 | 87 791 | 1243 | 1.42 | 0.025 | 88 359 | 1811 | 2.05 | 0.205 |

| Male | 669 | 34 | 5.08 | 648 | 13 | 2.01 | 651 | 16 | 2.46 | 653 | 18 | 2.76 | ||||

| Race | ||||||||||||||||

| White | 77 776 | 2249 | 2.89 | <0.0001 | 76 193 | 666 | 0.87 | <0.0001 | 76 600 | 1073 | 1.4 | <0.0001 | 77 071 | 1544 | 2 | <0.0001 |

| Black | 5646 | 280 | 4.96 | 5444 | 78 | 1.43 | 5491 | 125 | 2.28 | 5567 | 201 | 3.61 | ||||

| Other | 6419 | 129 | 2.01 | 6319 | 29 | 0.46 | 6351 | 61 | 0.96 | 6374 | 84 | 1.32 | ||||

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||||||||||||

| 1992 | 4756 | 127 | 2.67 | 0.346 | 4661 | 32 | 0.69 | 0.441 | 4681 | 52 | 1.11 | 0.002 | 4724 | 95 | 2.01 | <0.0001 |

| 1993 | 4439 | 117 | 2.64 | 4354 | 32 | 0.73 | 4381 | 59 | 1.35 | 4402 | 80 | 1.82 | ||||

| 1994 | 4283 | 113 | 2.64 | 4202 | 32 | 0.76 | 4231 | 61 | 1.44 | 4244 | 74 | 1.74 | ||||

| 1995 | 4359 | 125 | 2.87 | 4272 | 38 | 0.89 | 4298 | 64 | 1.49 | 4325 | 91 | 2.1 | ||||

| 1996 | 4306 | 127 | 2.95 | 4207 | 28 | 0.67 | 4245 | 66 | 1.55 | 4268 | 89 | 2.09 | ||||

| 1997 | 4371 | 119 | 2.72 | 4289 | 37 | 0.86 | 4314 | 62 | 1.44 | 4335 | 83 | 1.91 | ||||

| 1998 | 4308 | 135 | 3.13 | 4211 | 38 | 0.9 | 4238 | 65 | 1.53 | 4274 | 101 | 2.36 | ||||

| 1999 | 4452 | 135 | 3.03 | 4361 | 44 | 1.01 | 4378 | 61 | 1.39 | 4407 | 90 | 2.04 | ||||

| 2000 | 8833 | 298 | 3.37 | 8602 | 67 | 0.78 | 8666 | 131 | 1.51 | 8765 | 230 | 2.62 | ||||

| 2001 | 9186 | 295 | 3.21 | 8968 | 77 | 0.86 | 9026 | 135 | 1.5 | 9112 | 221 | 2.43 | ||||

| 2002 | 9236 | 267 | 2.89 | 9057 | 88 | 0.97 | 9060 | 91 | 1 | 9178 | 209 | 2.28 | ||||

| 2003 | 9211 | 274 | 2.97 | 9034 | 97 | 1.07 | 9048 | 111 | 1.23 | 9134 | 197 | 2.16 | ||||

| 2004 | 9036 | 272 | 3.01 | 8843 | 79 | 0.89 | 8897 | 133 | 1.49 | 8925 | 161 | 1.8 | ||||

| 2005 | 9065 | 254 | 2.8 | 8895 | 84 | 0.94 | 8979 | 168 | 1.87 | 8919 | 108 | 1.21 | ||||

| Stage | ||||||||||||||||

| I | 46 831 | 878 | 1.87 | <0.0001 | 46 237 | 284 | 0.61 | <0.0001 | 46 405 | 452 | 0.97 | <0.0001 | 46 545 | 592 | 1.27 | <0.0001 |

| II | 30 652 | 1012 | 3.3 | 29 918 | 278 | 0.93 | 30 158 | 518 | 1.72 | 30 327 | 687 | 2.27 | ||||

| III | 6710 | 337 | 5.02 | 6470 | 97 | 1.5 | 6512 | 139 | 2.13 | 6609 | 236 | 3.57 | ||||

| IV | 5648 | 431 | 7.63 | 5331 | 114 | 2.14 | 5367 | 150 | 2.79 | 5531 | 314 | 5.68 | ||||

| Estrogen receptor | ||||||||||||||||

| Positive | 61 660 | 1717 | 2.78 | <0.0001 | 60 445 | 502 | 0.83 | 0.007 | 60 796 | 853 | 1.4 | 61 138 | 1195 | 1.95 | 0.008 | |

| Negative | 12 108 | 421 | 3.48 | 11 820 | 133 | 1.13 | 11 870 | 183 | 1.54 | 0.503 | 11 961 | 274 | 2.29 | |||

| Unknown | 16 073 | 520 | 3.24 | 15 691 | 138 | 0.88 | 15 776 | 223 | 1.41 | 15 913 | 360 | 2.26 | ||||

| Charlson comorbidity | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 69 349 | 1992 | 2.87 | <0.0001 | 67 931 | 574 | 0.84 | 0.120 | 68 294 | 937 | 1.37 | 0.001 | 68 738 | 1381 | 2.01 | 0.008 |

| 1 | 14 516 | 435 | 3 | 14 219 | 138 | 0.97 | 14 286 | 205 | 1.43 | 14 375 | 294 | 2.05 | ||||

| 2+ | 5976 | 231 | 3.87 | 5806 | 61 | 1.05 | 5862 | 117 | 2 | 5899 | 154 | 2.61 | ||||

| Surgery | ||||||||||||||||

| Breast conserving | 42 518 | 999 | 2.35 | 41 842 | 323 | 0.77 | <0.0001 | 42 016 | 497 | 1.18 | <0.0001 | 42 217 | 698 | 1.65 | <0.0001 | |

| Mastectomy | 42 773 | 1331 | 3.11 | 41 797 | 355 | 0.85 | 42 092 | 650 | 1.54 | 42 345 | 903 | 2.13 | ||||

| No/unknown | 4550 | 328 | 7.21 | 4317 | 95 | 2.2 | 4334 | 112 | 2.58 | 4450 | 228 | 5.12 | ||||

| Radiotherapy | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 45 405 | 1307 | 2.88 | 0.067 | 44 438 | 340 | 0.77 | 0.001 | 44 718 | 620 | 1.39 | 0.523 | 44 971 | 873 | 1.94 | 0.016 |

| Unknown | 1313 | 51 | 3.88 | 1277 | 15 | 1.17 | 1278 | 16 | 1.25 | 1298 | 36 | 2.77 | ||||

| Yes | 43 123 | 1300 | 3.01 | 42 241 | 418 | 0.99 | 42 446 | 623 | 1.47 | 42 743 | 920 | 2.15 | ||||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 71 279 | 1527 | 2.14 | <0.0001 | 70 208 | 456 | 0.65 | <0.0001 | 70 495 | 743 | 1.05 | <0.0001 | 70 781 | 1029 | 1.45 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 18 562 | 1131 | 6.09 | 17 748 | 317 | 1.79 | 17 947 | 516 | 2.88 | 18 231 | 800 | 4.39 | ||||

| CVC | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 80 425 | 1789 | 2.22 | <0.0001 | 79 169 | 533 | 0.67 | <0.0001 | 79 537 | 901 | 1.13 | <0.0001 | 79 851 | 1215 | 1.52 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 9416 | 869 | 9.23 | 8787 | 240 | 2.73 | 8905 | 358 | 4.02 | 9161 | 614 | 6.7 | ||||

| ESAs | ||||||||||||||||

| No | 83 596 | 2177 | 2.6 | <0.0001 | 82 069 | 650 | 0.79 | <0.0001 | 82 447 | 1028 | 1.25 | <0.0001 | 82 912 | 1493 | 1.8 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 6245 | 481 | 7.7 | 5887 | 123 | 2.09 | 5995 | 231 | 3.85 | 6100 | 336 | 5.51 | ||||

TEE, thromboembolic event; PE, pulmonary embolism; DVT, deep vein thromboembolism; Nocases, number of cases; CVC, central venous catheter; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent.

In the multivariable analysis, we observed that men had an increased risk of developing a TEE compared with women (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.10–2.25); blacks had higher risk (OR 1.20; 95% CI 1.04–1.40), and other races had reduced risk (OR 0.75; 95% CI 0.62–0.90) when compared with whites. More advanced stages were associated with higher risk; using stage I as a reference, patients with stage II, III and IV breast cancer had 22%, 39% and 98% increased risk, respectively. Patients that did not undergo any breast surgery (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.34–1.91), and those who had CVC placed (OR 2.71, 95% CI 2.43–3.02), received chemotherapy (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.48–1.86) or ESAs (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.17–1.52), had increased risk for developing a TEE. Patients who had ER-negative tumors were less likely to have a TEE (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.73–0.96). When the analysis was carried out according to the different TEE categories, the observed estimates were similar; however, some of the associations did not achieve statistical significance. The multivariable analyses are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysisa of risk factors associated with different TEEs

| TEE (events = 2658), OR (95% CI) | PE (events = 773), OR (95% CI) | DVT (events = 1259), OR (95% CI) | Other/unclassified (events = 1829), OR (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 66–70 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 71–75 | 1.14 (1.03–1.28) | 1.20 (0.98–1.47) | 1.09 (0.94–1.27) | 1.18 (1.03–1.34) |

| 76–80 | 1.19 (1.06–1.33) | 1.31 (1.06–1.62) | 1.08 (0.91–1.27) | 1.22 (1.06–1.40) |

| >80 | 1.26 (1.12–1.43) | 1.36 (1.09–1.71) | 1.15 (0.96–1.37) | 1.27 (1.10–1.48) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Male | 1.57 (1.10–2.25) | 2.27 (1.29–3.99) | 1.50 (0.90–2.49) | 1.25 (0.77–2.02) |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 1.20 (1.04–1.40) | 1.23 (0.94–1.60) | 1.29 (1.04–1.60) | 1.20 (1.01–1.43) |

| Other | 0.75 (0.62–0.90) | 0.56 (0.38–0.83) | 0.72 (0.55–0.94) | 0.73 (0.58–0.92) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||

| 1992 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 1993 | 0.97 (0.75–1.25) | 1.03 (0.63–1.69) | 1.19 (0.82–1.74) | 0.88 (0.65–1.19) |

| 1994 | 0.95 (0.73–1.23) | 1.06 (0.64–1.73) | 1.26 (0.87–1.83) | 0.83 (0.61–1.14) |

| 1995 | 1.03 (0.80–1.32) | 1.22 (0.76–1.96) | 1.29 (0.89–1.87) | 1.00 (0.74–1.34) |

| 1996 | 1.03 (0.80–1.32) | 0.87 (0.52–1.45) | 1.34 (0.92–1.93) | 0.97 (0.72–1.30) |

| 1997 | 0.91 (0.71–1.18) | 1.08 (0.67–1.75) | 1.19 (0.82–1.74) | 0.84 (0.62–1.14) |

| 1998 | 1.04 (0.81–1.33) | 1.11 (0.69–1.79) | 1.25 (0.86–1.81) | 1.03 (0.78–1.38) |

| 1999 | 0.95 (0.74–1.23) | 1.18 (0.75–1.88) | 1.07 (0.74–1.56) | 0.84 (0.63–1.14) |

| 2000 | 0.90 (0.72–1.12) | 0.80 (0.52–1.24) | 0.95 (0.68–1.33) | 0.90 (0.70–1.17) |

| 2001 | 0.85 (0.68–1.06) | 0.89 (0.58–1.36) | 0.91 (0.65–1.27) | 0.84 (0.65–1.08) |

| 2002 | 0.74 (0.59–0.93) | 0.98 (0.65–1.50) | 0.59 (0.42–0.85) | 0.76 (0.58–0.98) |

| 2003 | 0.75 (0.60–0.94) | 1.07 (0.71–1.62) | 0.72 (0.51–1.01) | 0.71 (0.54–0.92) |

| 2004 | 0.72 (0.57–0.90) | 0.84 (0.55–1.29) | 0.84 (0.60–1.18) | 0.55 (0.42–0.72) |

| 2005 | 0.66 (0.53–0.83) | 0.88 (0.57–1.35) | 1.05 (0.75–1.46) | 0.37 (0.27–0.49) |

| Stage | ||||

| I | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| II | 1.22 (1.10–1.35) | 1.08 (0.90–1.30) | 1.24 (1.08–1.42) | 1.21 (1.07–1.36) |

| III | 1.39 (1.20–1.62) | 1.26 (0.96–1.65) | 1.13 (0.91–1.41) | 1.47 (1.23–1.76) |

| IV | 1.98 (1.68–2.33) | 1.55 (1.14–2.10) | 1.50 (1.17–1.93) | 2.15 (1.78–2.59) |

| Estrogen receptor | ||||

| Positive | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Negative | 0.84 (0.73–0.96) | 0.92 (0.72–1.18) | 0.72 (0.59–0.88) | 0.77 (0.65–0.92) |

| Unknown | 0.80 (0.61–1.04) | 1.18 (0.67–2.06) | 0.77 (0.52–1.13) | 0.68 (0.50–0.92) |

| Charlson comorbidity | ||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 1.03 (0.92–1.14) | 1.13 (0.94–1.37) | 1.03 (0.88–1.20) | 1.01 (0.89–1.15) |

| 2+ | 1.21 (1.05–1.40) | 1.14 (0.87–1.49) | 1.34 (1.10–1.64) | 1.17 (0.99–1.40) |

| Surgery | ||||

| Breast conserving | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Mastectomy | 1.05 (0.95–1.16) | 0.98 (0.81–1.18) | 1.09 (0.94–1.27) | 1.02 (0.90–1.15) |

| No surgery/unknown | 1.60 (1.34–1.91) | 1.88 (1.36–2.60) | 1.43 (1.08–1.89) | 1.52 (1.23–1.87) |

| Radiation theorapy | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Unknown | 1.15 (0.84–1.57) | 1.37 (0.78–2.39) | 0.83 (0.49–1.41) | 1.13 (0.78–1.63) |

| Yes | 1.07 (0.97–1.17) | 1.29 (1.08–1.53) | 1.07 (0.93–1.23) | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.66 (1.48–1.86) | 1.70 (1.38–2.08) | 1.72 (1.47–2.03) | 1.71 (1.50–1.96) |

| CVC placement | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 2.71 (2.43–3.02) | 2.71 (2.23–3.30) | 2.14 (1.83–2.51) | 2.79 (2.46–3.17) |

| ESAs use | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.33 (1.17–1.52) | 1.08 (0.85–1.37) | 1.52 (1.27–1.83) | 1.39 (1.19–1.61) |

Adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, education level, poverty level, geographical location, year of diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, estrogen and progesterone receptor status, comorbidities (Charlson index), surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, CVC placement and the use of ESAs.

TEE, thromboembolic event; PE, pulmonary embolism; DVT, deep vein thromboembolism; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CVC, central venous catheter; ESAs, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents.

discussion

Our study shows that among patients ≥66 years old with breast cancer, the incidence of TEE is 2.96% in the first year of diagnosis. We observed that the incidence is even higher among males and black patients; those with stage IV disease, CVC placement and those receiving chemotherapy and ESAs were at even higher risk. The magnitude of the observed risk was notable. In a multivariable analysis, patients with stage II, III and IV disease had 22%, 39% and 98% increase in risk. The risk among males and black patients was increased 57% and 20%, respectively. The associations with different treatment modalities were also significant; the use of chemotherapy increased the risk by 66%, ESAs increased it by 33% and the use of CVC increased the risk by 170%.

The observed incidence of TEEs is higher than that previously reported. In a large population-based study, Chew et al. [12] observed that among 108 255 patients with breast cancer, the 2-year cumulative risk of a TEE was 1.2%. These results are similar to those observed in clinical trials of patients receiving adjuvant hormonal therapy (1.3%) [20]. The reported incidence of TEE in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy is 2.1% [13], and for patients with metastatic disease it is 4.4% [14]. This contrasts with our observed TEE incidence of 6.09% in patients receiving chemotherapy and 7.63% in those with metastatic disease. Different studies use different definitions for TEEs, and inter-study comparisons are difficult. Also, it is important to note that our patient population included exclusively patients aged ≥66 years, representing a high-risk cohort, therefore they are not comparable with younger and healthier patients included in clinical trials.

The first months after a cancer diagnosis are considered the highest risk period for developing TEEs [6, 12]. Consistent with prior reports, we observed that 39.5% of the events occurred during the first 3 months after diagnosis. Some of the hypotheses to explain this phenomenon include the possibility that cancer cells cause activation of the clotting system via humoral and mechanical effects [2]. Other explanations include that in the early months after the diagnosis of cancer, surgery may take place and the inflammatory response can favor a procoagulant state; surgery is also associated with increased risk of TEEs secondary to immobility. Another possible explanation to this peak in the early months after diagnosis is the beginning of active treatment, in particular chemotherapy; the possible invasive interventions to complete the diagnosis work-up and the direct effect of injury after a CVC placement or infections may also play a role [9, 21–24].

A notable finding of this analysis is the increased risk of TEE in male patients. Observational studies including patients with different types of cancer report similar rates of TEE among males and females [1, 6, 22, 25]. In a large study [8] evaluating risk factors for TEE in 1 015 598 hospitalized cancer patients, gender was a predictor of venous thromboembolism, with females having a 14% increase in risk compared with males. It should be noted that a different pattern was observed in our study. Male breast cancer is a rare disease, and ∼1% of all the breast cancers are diagnosed in men. Breast cancer in males is more likely to express ER and PR, with rates as high as 90% [26]. It is accepted that two major factors involved in the stimulation of ER-positive breast cancers are ER signaling and circulating estrogen [27, 28]. There is evidence that extraglandularly produced estradiol-17β and estrone stimulate breast growth in males [29] and that male patients with breast cancer have significantly higher circulating levels of total and free estradiol than non-cancer males [30]. It is possible that risk factors or hormonal variations associated with male breast cancer are also associated with TEE. A study by Kyrle et al. [31] in non-cancer patients reported that males had a higher incidence of recurrent idiopathic venous thromboembolism than women. Similarly, Christiansen et al. [32] observed that in a young non-cancer cohort, males had higher rates of recurrent TEE compared with women. To the best of our knowledge, our observation has not been studied specifically in patients with breast cancer and represents an interesting finding that needs to be confirmed.

In our study, rates of TEE appear to be higher in black patients compared with whites. This observation has been reported by others [7, 8]. Some have suggested that such differences may be related to the type of cancer [6]. However, in a large cohort of breast cancer patients, black patients had a borderline significant increase of 30% in the risk of TEE compared with whites [12]. Comorbidities are another well-studied risk factor for the development of TEEs. The presence of comorbid conditions influences the development of TEEs in patients with different types of cancer. Our data confirm this supposition and provide evidence that the observed increase in risk is associated with an increased number of comorbidities [6, 7, 12, 22, 33–36]. To evaluate comorbidities, we used Klabunde's adaptation of the Charlson index; this scoring system was developed to incorporate the diagnostic and procedure data contained in Medicare claims, to model the 2-year non-cancer mortality [17]. We observed that patients with a Charlson score of 1 did not have a significant increase in risk; however, those with a score ≥2 had 21% higher probability of developing a TEE.

Different treatment strategies have been associated with TEEs, and patients receiving systemic chemotherapy are considered to be at increased risk [1, 2, 37]. In a retrospective study evaluating patients receiving chemotherapy, the reported TEE rate for breast cancer patients was 6% [38], a number nearly identical to what we observed in our study. The exact pathophysiological mechanisms to explain the observed excess of TEEs in patients receiving chemotherapy are not well elucidated, but prothrombotic alterations in coagulation factors, anticoagulant proteins and endothelial cells have been shown to occur following the administration of cytotoxic agents [39–43]. It has been suggested that a prechemotherapy platelet count ≥350 000 and a hemoglobin level <10 g/dl are risk factors for the development of chemotherapy-associated TEEs [7, 25, 35]. Unfortunately, in the SEER-Medicare dataset, no information is available on patients' hematological parameters, so it was not possible to take these factors into consideration in our analysis.

ESAs have been widely used to increase hemoglobin values and reduce transfusion requirements in cancer patients [44–46]. Reports have raised safety concerns as results suggest that the use of ESAs is associated with TEEs [47–49]. In a recent meta-analysis that included 4610 cancer patients, Bennett et al. [48] reported that patients who received ESAs had a higher risk of TEEs (hazard ratio 1.57; 95% CI 1.31–1.87). Our results are consistent with such a risk estimate; we observed that patients who received ESAs had a 33% increase of developing a TEE and a 52% higher risk of DVT compared with patients that did not receive ESAs.

CVC placement is another intervention that has consistently been associated with an increased risk for TEE [10, 50]; we observed that it conferred a 2.7-fold increase in risk. Some of the factors associated with this phenomenon are venous stasis and endothelial injury. However, recent reports associate number of attempts, left side placement and catheter tip position with an increased risk [9]. Unfortunately, we were not able to include those factors in our analysis. Despite the clear relationship between CVC placement and the development of a TEE, no differences in CVC-related TEE rates have been seen in double-blind placebo-controlled trials in cancer patients randomly assigned to receive enoxaparin [51] for 6 weeks or dalteparin [52] for 16 weeks. Current guidelines do not recommend prophylaxis for cancer patients with a CVC [53] but clinical trials should continue to address this question given the important morbidity associated with CVCs.

Our results raise the question of the use of primary prophylaxis in high-risk patients. Our study describes the risk of TEEs in a high-risk breast cancer patient population, and does not represent a valid scoring system, therefore no treatment recommendations can be made based on our results. However, as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines suggest, inpatient prophylactic therapy should be administered to all patients with active diagnosis of cancer who do not have a contraindication to such therapy [53]. There is unfortunately no data to support extended prophylaxis for medical oncology patients in the outpatient setting [53]. Different scoring systems are available in which individual risk factors are assigned weighted scores, and they provide support for the use of prophylaxis in cancer patients [54–56]; however, none of those score systems have been validated in cancer patients. Khorana et al. [35] reported on a model in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy; if validated in future studies, this score could help identify patients in whom primary prophylaxis should be recommended. Importantly, randomized clinical trials evaluating this concept are warranted.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study examining the risk factors associated with different TEEs within the first year of diagnosis in breast cancer patients aged ≥66 years. One of the strengths of this study is that it involves a large unselected population-based cohort of patients, likely reflecting real clinical practice. It is important to mention that, for the same reasons, our cohort includes a high-risk population, and it is likely that age and comorbidities contributed to the higher incidence of TEEs seen.

A limitation of our study is that the SEER-Medicare data do not allow for assessment of the extent of the disease, the severity of outcomes, or an analysis that takes into account the use of thromboprophylaxis, the patient's history of prior TEEs and performance status or hematological parameters. It is possible that factors such as a large tumor burden or genetic predisposition may impact TEE incidence, but we were not able to adjust for such factors. An inherent limitation of claims-based research is the possible heterogeneity in the diagnosis methods used to identify events. We used established diagnosis codes to identify TEE cases and do not believe that the possible heterogeneity in the diagnosis methods could have caused a significant change in our estimates. A limitation of our study is that we could not include data on tamoxifen use, a medication with known prothrombotic effects. It is possible that the lower rate of TEE seen in patients with ER-negative tumors is a reflection of the increased risk seen in ER+ patients as a result of tamoxifen treatment. As a way to take this into account, we adjusted for ER status in the multivariable model and also included the year of diagnosis as we suspect that the proportion of patients taking tamoxifen decreased in recent years as the use of aromatase inhibitors has become the standard of care in postmenopausal patients. We also carried out a stratified analysis according to ER status (data not shown) and observed that the magnitude and direction of the estimates remained very similar. The effect of age, race, stage, comorbidities, chemotherapy and ESAs use and CVC placement was similar when patients with ER-positive, ER-negative and ER-unknown tumors were analyzed separately, validating our results. Also, the results of our study may not be applicable to a population of younger, and in general, healthier patients. Additional studies are needed to confirm these findings and assess the risk of different TEEs in younger breast cancer patients.

In summary, our results demonstrate that TEEs are a complication seen in patients with breast cancer. In this cohort of patients, the first 3 months after diagnosis were associated with the highest event incidence. Males, black patients and those with advanced stages or positive hormone receptor status are at increased risk. Other subgroups of patients at significant risk are those receiving chemotherapy or ESAs and those with CVC placement. TEEs in breast cancer patients represent a substantial clinical problem and much work needs to be done to reduce the burden of TEEs. Better risk assessment tools need to be developed to identify high-risk populations who could benefit from pharmacological prophylactic treatment.

funding

National Institutes of Health (K07-CA109064) to S.H.G.

diclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services Inc.; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

References

- 1.Sallah S, Wan JY, Nguyen NP. Venous thrombosis in patients with solid tumors: determination of frequency and characteristics. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87:575–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S, Rosendaal FR. Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA. 2005;293:715–722. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trousseau A. Phlegmasia Alba Dolems: Lectures on Clinical Medicine. London: The New Sydenham Society; 1868. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winter PC. The pathogenesis of venous thromboembolism in cancer: emerging links with tumour biology. Hematol Oncol. 2006;24:126–133. doi: 10.1002/hon.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, et al. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:809–815. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chew HK, Wun T, Harvey D, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism and its effect on survival among patients with common cancers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:458–464. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khorana AA, Connolly GC. Assessing risk of venous thromboembolism in the patient with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4839–4847. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Culakova E, et al. Frequency, risk factors, and trends for venous thromboembolism among hospitalized cancer patients. Cancer. 2007;110:2339–2346. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee AY, Levine MN, Butler G, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of catheter-related thrombosis in adult patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1404–1408. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.5600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shivakumar SP, Anderson DR, Couban S. Catheter-associated thrombosis in patients with malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4858–4864. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein PD, Beemath A, Meyers FA, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in patients hospitalized with cancer. Am J Med. 2006;119:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chew HK, Wun T, Harvey DJ, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism and the impact on survival in breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:70–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clahsen PC, van de Velde CJ, Julien JP, et al. Thromboembolic complications after perioperative chemotherapy in women with early breast cancer: a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer Cooperative Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1266–1271. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.6.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine M, Hirsh J, Gent M, et al. Double-blind randomised trial of a very-low-dose warfarin for prevention of thromboembolism in stage IV breast cancer. Lancet. 1994;343:886–889. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2007–2008. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, et al. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Med Care. 1993;31:732–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. discussion 1081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, et al. A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1081–1092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agnelli G, Bolis G, Capussotti L, et al. A clinical outcome-based prospective study on venous thromboembolism after cancer surgery: the @RISTOS project. Ann Surg. 2006;243:89–95. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000193959.44677.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroger K, Weiland D, Ose C, et al. Risk factors for venous thromboembolic events in cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:297–303. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linenberger ML. Catheter-related thrombosis: risks, diagnosis, and management. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4:889–901. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2006.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Rooden CJ, Schippers EF, Barge RM, et al. Infectious complications of central venous catheters increase the risk of catheter-related thrombosis in hematology patients: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2655–2660. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Culakova E, Lyman GH. Risk factors for chemotherapy-associated venous thromboembolism in a prospective observational study. Cancer. 2005;104:2822–2829. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giordano SH. Male breast cancer: it's time for evidence instead of extrapolation. Onkologie. 2008;31:505–506. doi: 10.1159/000153894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dimitrov NV, Colucci P, Nagpal S. Some aspects of the endocrine profile and management of hormone-dependent male breast cancer. Oncologist. 2007;12:798–807. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsing AW, McLaughlin JK, Cocco P, et al. Risk factors for male breast cancer (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9:269–275. doi: 10.1023/a:1008869003012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee PA. The relationship of concentrations of serum hormones to pubertal gynecomastia. J Pediatr. 1975;86:212–215. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nirmul D, Pegoraro RJ, Jialal I, et al. The sex hormone profile of male patients with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1983;48:423–427. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1983.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyrle PA, Minar E, Bialonczyk C, et al. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in men and women. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2558–2563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christiansen SC, Cannegieter SC, Koster T, et al. Thrombophilia, clinical factors, and recurrent venous thrombotic events. JAMA. 2005;293:2352–2361. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.19.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alcalay A, Wun T, Khatri V, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with colorectal cancer: incidence and effect on survival. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1112–1118. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chew HK, Davies AM, Wun T, et al. The incidence of venous thromboembolism among patients with primary lung cancer. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:601–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, et al. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood. 2008;111:4902–4907. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez AO, Wun T, Chew H, et al. Venous thromboembolism in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haddad TC, Greeno EW. Chemotherapy-induced thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2006;118:555–568. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otten HM, Mathijssen J, ten Cate H, et al. Symptomatic venous thromboembolism in cancer patients treated with chemotherapy: an underestimated phenomenon. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:190–194. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canobbio L, Fassio T, Ardizzoni A, et al. Hypercoagulable state induced by cytostatic drugs in stage II breast cancer patients. Cancer. 1986;58:1032–1036. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860901)58:5<1032::aid-cncr2820580509>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feffer SE, Carmosino LS, Fox RL. Acquired protein C deficiency in patients with breast cancer receiving cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil. Cancer. 1989;63:1303–1307. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890401)63:7<1303::aid-cncr2820630713>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lazo JS. Endothelial injury caused by antineoplastic agents. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35:1919–1923. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90720-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rella C, Coviello M, Giotta F, et al. A prothrombotic state in breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;40:151–159. doi: 10.1007/BF01806210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers JS, II, Murgo AJ, Fontana JA, Raich PC. Chemotherapy for breast cancer decreases plasma protein C and protein S. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:276–281. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinbrook R. Erythropoietin, the FDA, and oncology. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2448–2451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leyland-Jones B, Semiglazov V, Pawlicki M, et al. Maintaining normal hemoglobin levels with epoetin alfa in mainly nonanemic patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy: a survival study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5960–5972. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vansteenkiste J, Pirker R, Massuti B, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase III trial of darbepoetin alfa in lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1211–1220. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.16.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khuri FR. Weighing the hazards of erythropoiesis stimulation in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2445–2448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bennett CL, Silver SM, Djulbegovic B, et al. Venous thromboembolism and mortality associated with recombinant erythropoietin and darbepoetin administration for the treatment of cancer-associated anemia. JAMA. 2008;299:914–924. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bohlius J, Schmidlin K, Brillant C, et al. Recombinant human erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and mortality in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1532–1542. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60502-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verso M, Agnelli G. Venous thromboembolism associated with long-term use of central venous catheters in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3665–3675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verso M, Agnelli G, Bertoglio S, et al. Enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism associated with central vein catheter: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4057–4062. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karthaus M, Kretzschmar A, Kroning H, et al. Dalteparin for prevention of catheter-related complications in cancer patients with central venous catheters: final results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:289–296. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Venous Thromboembolic Disease. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; www.nccn.org V.1.2010 (15 September 2010, date last accessed) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caprini JA, Arcelus JI, Reyna JJ. Effective risk stratification of surgical and nonsurgical patients for venous thromboembolic disease. Semin Hematol. 2001;38:12–19. doi: 10.1016/s0037-1963(01)90094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kucher N, Koo S, Quiroz R, et al. Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:969–977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Samama MM, Dahl OE, Mismetti P, et al. An electronic tool for venous thromboembolism prevention in medical and surgical patients. Haematologica. 2006;91:64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]