Abstract

Context:

Previous studies have suggested that estrogen levels may be higher in African-American women (AAW) compared with Caucasian women (CW), but none have systematically examined estrogen secretion across the menstrual cycle or in relation to other reproductive hormones.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to compare estradiol (E2), progesterone (P), gonadotropins, androstenedione (a'dione), inhibins, and SHBG levels between AAW and CW across the menstrual cycle.

Design, Setting, and Subjects:

Daily blood samples were collected from regularly cycling AAW (n = 27) and CW (n = 27) for a full menstrual cycle, and serial ultrasounds were performed.

Main Outcome Measures:

Comparison of E2, P, LH, FSH, SHBG, inhibin A, inhibin B, and a'dione levels.

Results:

AAW and CW were of similar age (27.2 ± 0.6 yr, mean ± sem) and body mass index (22.7 ± 0.4 kg/m2). All subjects grew a single dominant follicle and had comparable cycle (25–35 d) and follicular phase (11–24 d) lengths. E2 levels were significantly higher in AAW compared with CW (P = 0.02) with the most pronounced differences in the late follicular phase (225.2 ± 14.4 vs. 191.5 ± 10.2 pg/ml; P = 0.02), midluteal phase (211.9 ± 22.2 vs.150.8 ± 9.9, P < 0.001), and late luteal phase (144.4 ± 13.2 vs. 103.5 ± 8.5, P = 0.01). Although LH, FSH, inhibins A and B, P, a'dione, and SHBG were not different between the two groups, the a'dione to E2 ratio was lower in AAW (P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

Estradiol is higher in AAW compared with CW across the menstrual cycle. Higher estradiol in the face of similar androstenedione and FSH levels suggests enhanced aromatase activity in AAW. Such differences may contribute to racial disparities in bone mineral density, breast cancer, and uterine leiomyomas.

Several independent lines of evidence have suggested that reproductive endocrine dynamics may differ between African-American women (AAW) and Caucasian (CW) women. Epidemiological studies have reported a higher incidence of several estrogen-responsive pathologies, such as leiomyomas (1) and breast cancer (2), as well as a higher bone mineral density (3), an earlier age of puberty (4), and an increase in dizyogtic twinning (5, 6) in premenopausal AAW compared with CW.

In an attempt to understand these associations, a number of studies have sought to determine whether there are differences in estradiol (E2) levels between reproductive aged AAW and CW with variable results. In four relatively large studies E2 levels were higher in AAW compared with CW (7–10), whereas other studies either reported lower E2 levels in AAW (11, 12) or found no difference between the two groups (13–15). Assessment of a small number of blood samples across the cycle is a significant factor contributing to the lack of consistency between these studies because there are dynamic changes in E2 levels that occur across a normal menstrual cycle. An additional consideration is that the majority of previous studies did not control for age and body mass index (BMI) and may have included racially admixed women because classification was based only on the subject's race without generational history. In the most comprehensive study to date, Reutman et al. (16) reported no difference in estrone conjugates measured in daily urine samples between AAW and CW, but studies were not controlled for BMI or smoking.

To further address the hypothesis that E2 levels are increased in AAW and to advance our understanding of potential physiological mechanisms that may underlie racial differences in reproductive hormone levels in women, we have examined ovarian and pituitary reproductive hormones through daily blood sampling across the menstrual cycle in age- and BMI-matched, regularly cycling AAW and CW. These studies demonstrate that E2 levels are significantly higher in AAW compared with CW, which cannot be explained by differences in the number of dominant follicles or LH, FSH, or androstenedione (a'dione) levels. The observed decrease in the a'dione to E2 ratio among AAW compared with CW, despite similar FSH levels, suggests an inherent increase in aromatase activity in AAW.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

The study population consisted of 27 AAW and 27 CW. Subjects were classified as either African-American or Caucasian if they, their parents, and both sets of grandparents self-identified as such. Subjects with mixed racial backgrounds were excluded from the study. All subjects were healthy, euthyroid, and normoprolactinemic premenopausal women (aged 21–35 yr). Subjects had regular menstrual cycles, 25–35 d in length, with ovulation in the preceding cycle confirmed by urine LH kits and/or a serum progesterone (P) greater than 6 ng/ml (19.1 nmol/liter). Subjects were nonobese (BMI <30 kg/m2), did not exercise excessively (17), were not hirsute, and were nonsmokers. None of the women had taken birth control pills for the 2 months before the study, and they were not on any other medications known to interact with the reproductive axis. Subjects were also instructed to refrain from using estrogen-containing creams, hair products, and herbal supplements during the study. Subjects took ferrous gluconate (324 mg/d) for the study duration. Six subjects reported in the current manuscript (two AAW and four CW) participated in previous studies in our unit (18). These subjects met all of the criteria required for the current study including information regarding racial background (three generations), ultrasound data that documented growth of a single dominant follicle, and adequate sample volume for measurement of a'dione and SHBG, which were not measured in previous studies.

The protocol was approved by the Subcommittee on Human Studies of the Massachusetts General Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from each subject before her participation in the study.

Experimental protocol

Daily blood samples were collected from each subject beginning 1 wk before her expected menses and continuing until the following menses. On average, fewer than two samples were missed per subject. All blood samples were assayed for E2, P, a'dione [the major androgenic secretory product of the ovary (19)], FSH, LH, inhibin A, inhibin B, and SHBG. Estrone (E1) was measured in pooled samples at three points in the menstrual cycle [early follicular phase (d 1–3), periovulatory (d −1, 0, and +1 from ovulation), and midluteal (d −1, 0, and +1 from the midpoint of the luteal phase)].

Subjects underwent two to three transvaginal ultrasounds in the follicular phase to record the number and size(s) of the dominant follicle and to document polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) (20). The size of the dominant follicle on the day of ovulation [defined using the day of the midcycle LH peak, the midcycle FSH peak, the day of or the day after the preovulatory E2 peak, and/or the day on which P doubled or exceeded 0.6 ng/ml (1.9 nmol/liter, as previously described [21])] was estimated by assuming a growth rate of 2 mm/d of the largest follicle greater than 10 mm (22).

Assays

E2 was measured by immunoassay (AxSym; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) as previously described (23). The functional sensitivity of the assay was 20 pg/ml (73.4 pmol/liter). The interassay coefficients of variation (CV) were 10.2, 6.5, and 8.2% for quality control sera containing 81, 284, and 683 pg/ml (297, 1042, and 2507 pmol/liter), respectively. Serum E1 was measured using an RIA (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX) as previously described (24). The interassay CV were 9.6 and 4.1% for quality control sera containing 34.1 and 293.1 pg/ml (126 and 1084 pmol/liter), respectively. A'dione was measured by a solid-phase 125I RIA (Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA) as previously described (25) with an assay sensitivity of 0.04 ng/ml and intra- and interassay CV of 3.2–9.4 and 4.1–15.6%, respectively, within the range of 0.3–7.6 ng/ml (1.05–26.9 nmol/liter). LH and FSH were measured by a two-site monoclonal nonisotopic system (AxSym; Abbott Laboratories) as previously described (26) with assay sensitivities of 0.3 and 0.7 IU/liter for LH and FSH, respectively. LH and FSH levels are expressed in international units per liter as equivalents of the Second International Pituitary Reference preparations 80/552 and 78/549 for LH and FSH, respectively.

SHBG and P were assayed using a chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (ELISA; Immulite; Diagnostic Products Corp.). The lower limit of detection of SHBG was 0.2 nmol/liter and the ranges of the inter- and intraassay CV for SHBG were 5.8–13.0 and 4.1–7.7% for concentrations between 4.5 and 121 nmol/liter. The sensitivity of the P assay was 0.2 ng/ml (0.6 nmol/liter). The ranges of inter- and intraassay CV for P were 5.8–16 and 5.0–16% for concentrations between 0.8 and 33 ng/ml (2.5–104.9 nmol/liter). Inhibin A was measured by ELISA (Serotec, Oxford, UK), as previously described (27) using a lyophilized human follicular fluid calibrator standardized as equivalents of the World Health Organization recombinant human inhibin A preparation 91/624. The sensitivity of the assay was 0.6 IU/ml. The intra- and interassay CV were both less than 10%. Inhibin B was measured by ELISA (Serotec) as previously described with a limit of detection of 16 pg/ml (28).

Data analysis

Using previously collected data from a large sample of CW studied across the menstrual cycle (n = 81), we determined that 25 women per group would be necessary to identify a 20% difference in E2 levels, the primary outcome measure, between AAW and CW with 80% power at a significance level of 0.05. This sample size also provides 80% power to detect a 10% difference in mean late follicular phase LH and FSH levels.

Daily samples were compared between AAW and CW before and after normalizing to a 28-d cycle length with the day of ovulation set as d 0, as previously described (29). Using these normalized cycle days, mean hormone levels were determined for the early (d −13 to −9), mid- (d −8 to −5), and late (d −4 to −1) follicular phase, and early (d 1–4), mid- (d 5–9), and late (d 10–14) luteal phase. For each subject, the a'dione and E2 were averaged for the days included in each cycle phase and the a'dione to E2 ratio was then calculated in each phase as an index of aromatase activity. The P to a'dione ratio, an index of 17α-hydroxylase/17, 20-lyase activity, was similarly calculated for each part of the luteal phase. The a'dione to E1 ratio and the E1 to E2 ratio were calculated from 3-d pools assayed for E1 and the mean of the corresponding 3 d for a'dione or E2 as appropriate. The a'dione to E1 ratio was calculated to corroborate results from the daily a'dione to E2 ratio, whereas the E1 to E2 ratio is a marker of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (17βHSD1) activity.

Results that were not normally distributed were log transformed before analysis. Results in AAW and CW were compared using ANOVA for repeated measures with Tukey's post hoc testing. Age and BMI comparisons were performed using unpaired t tests. A mixed-model analysis was then used to determine the impact of BMI and age on significant results. A P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Results are expressed as the mean ± sem unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Menstrual cycle characteristics

The AAW and CW were of similar age and BMI (Table 1). All subjects demonstrated normal menstrual cycles with an average length of 29.4 ± 2.8 d [mean ± sd (range 25–35)]. Ovulation was confirmed by a rise in P to a luteal peak of 17.0 ± 0.9 ng/ml (54.0 ± 2.9 nmol/liter). There were no differences in the length of the total cycle, follicular phase, or luteal phase between the two groups (Table 1). Serial pelvic ultrasounds demonstrated growth of a single dominant follicle in all women. There was no difference in the final preovulatory day on which the ultrasound was performed (−1.4 ± 0.5 vs. −1.6 ± 0.4 d from ovulation in AAW and CW, respectively) and no difference in the estimated maximum size of the dominant follicle between AAW and CW (Table 1). PCOM was present in a similar proportion of AAW and CW (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of AAW and CW

| AAW | CW | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 27 | 27 | |

| Age (yr) | 27.0 ± 4.5 | 27.4 ± 4.1 | 0.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.4 ± 3.1 | 22.1 ± 2.6 | 0.1 |

| Cycle length (d) | 29.3 ± 2.8 | 29.4 ± 2.8 | 0.8 |

| Follicular phase (d) | 15.4 ± 2.8 | 16.0 ± 2.9 | 0.4 |

| Luteal phase (d) | 13.9 ± 1.4 | 13.4 ± 2.2 | 0.4 |

| PCOM (%)a | 78 | 82 | 1.0 |

| Dominant follicle (mm)b | 23.1 ± 3.5 | 23.9 ± 3.4 | 0.1 |

Values are expressed as mean ± sd. P values represent African-American vs. Caucasian comparisons.

PCOM is based on Rotterdam criteria.

Dominant follicle size is predicted as described in the text.

Hormone measurements

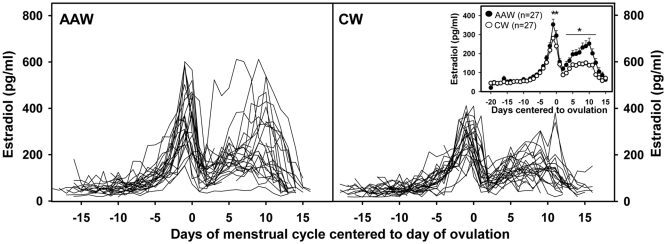

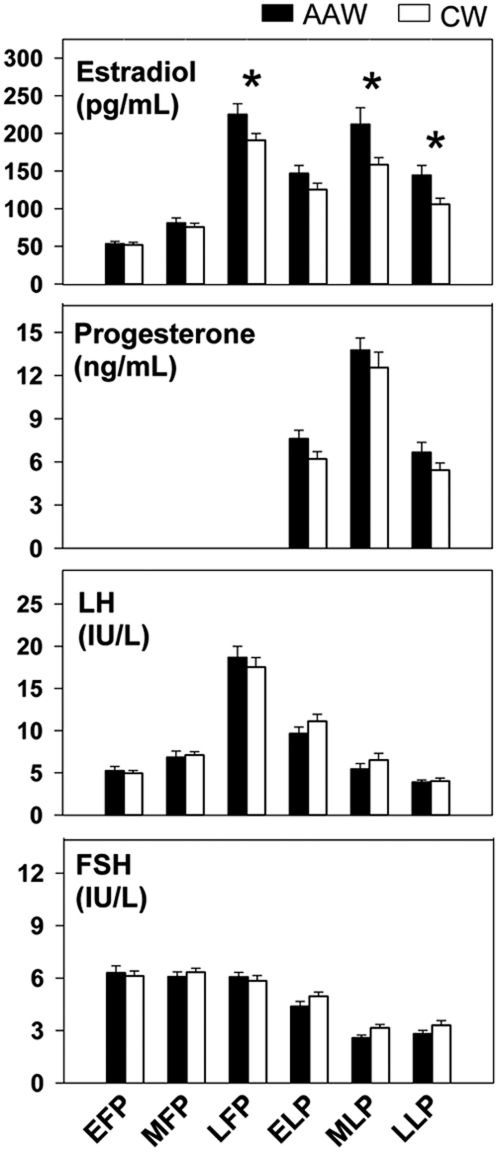

Analysis of daily samples across the menstrual cycle demonstrated higher E2 in AAW compared with CW (P = 0.02), accounted for by significant differences at the time of the preovulatory peak and in the luteal phase (Fig. 1). These findings were confirmed when data were analyzed in relation to cycle phase (which controls for variations in cycle length between subjects) such that E2 was significantly affected by both cycle phase (P < 0.001) and race (P = 0.02). As expected, there was an increase in E2 in all women across the follicular phase (P < 0.01) followed by a decline in the early luteal phase (P < 0.001) and a further rise in the midluteal phase (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). There was an interaction between race and cycle phase (P = 0.01) such that the most dramatic differences were observed in the late follicular phase [225.2 ± 14.4 (827 ± 53 pmol/liter) vs. 191.5 ± 10.2 pg/ml (703 ± 37 pmol/liter) in AAW vs. CW, respectively; P = 0.02], midluteal phase [211.9 ± 22.0 (778 ± 81 pmol/liter) vs. 150.8 ± 9.9 pg/ml (544 ± 36 pmol/liter); P < 0.001], and late luteal phase [144.4 ± 13.2 (530 ± 48 pmol/liter) vs. 103.5 ± 8.5 pg/ml (380 ± 31 pmol/liter); P = 0.01; Fig. 2]. All comparisons remained significant after adjusting for age and BMI. Despite the overall increase in E2 across the cycle in AAW, the percent change in E2 from one cycle phase to the next was not significantly different between AAW and CW.

Fig. 1.

E2 levels centered to ovulation in all AAW and CW, as indicated, showing higher E2 levels in AAW. The inset indicates the mean (sem) for the two groups and shows that differences are most pronounced during the preovulatory peak and in the luteal phase. *, P < 0.05 for differences between AAW and CW at designated cycle days in post hoc analyses; **P < 0.01.

Fig. 2.

E2 levels, normalized to the cycle phase, were significantly higher in AAW compared with CW across the cycle (P = 0.02), whereas there were no differences in P, FSH or LH. EFP, Early follicular phase; MFP, midfollicular phase; LFP, late follicular phase; ELP, early luteal phase; MLP, midluteal phase; LLP, late luteal phase. *, P < 0.02 for differences between AAW and CW in post hoc analyses.

The expected dynamic changes in P, FSH, and LH were observed across the cycle, with no differences between AAW and CW (Fig. 2). Similarly, the patterns of a'dione, inhibin A, and inhibin B varied across the cycle, whereas SHBG was not influenced by cycle phase (Table 2). There were no differences in a'dione, inhibin A, inhibin B, and SHBG between AAW and CW. E1 was measured in a subset of women (17 AAW and 15 CW) at three time points during the cycle. E1 was not significantly different between the two groups in the early follicular phase [156.4 ± 60.7 (578.4 ± 224.5 pmol/liter) vs. 96.4 ± 12.5 pg/ml (356.5 ± 46.2 pmol/liter) in AAW vs. CW, P = 0.3] or periovulatory phase [409.8 ± 49.2 (1515.5 ± 182.0 pmol/liter) vs. 382.7 ± 84.2 pg/ml (1415.3 ± 311.4 pmol/liter); P = 0.7] but was higher in AAW in the midluteal phase [335.6 ± 39.0 (1241.1 ± 144.2 pmol/liter) vs. 213.1 ± 33.4 pg/ml (787.7 ± 123.5 pmol/liter); P = 0.02].

Table 2.

Mean (sem) levels of a'dione, inhibin A, inhibin B, and SHBG did not differ between AAW and CW in any cycle phase

| Cycle phase | a'dione |

Inhibin A |

Inhibin B |

SHBG |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAW | CW | AAW | CW | AAW | CW | AAW | CW | |

| EFP | 1.9 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 116.1 (9.6) | 110.8 (9.1) | 44.4 (5.4) | 52.9 (4.9) |

| MFP | 2.2 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.2) | 140.0 (13.1) | 159.5 (20.1) | 44.3 (5.2) | 50.8 (4.6) |

| LFP | 2.4 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.2) | 3.4 (0.4) | 4.6 (0.5) | 147.7 (16.3) | 129.2 (10.2) | 41.2 (4.7) | 46.6 (4.3) |

| ELP | 2.4 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.3) | 7.1 (1.0) | 7.0 (1.0) | 122.2 (21.3) | 87.9 (8.7) | 47.2 (5.6) | 52.0 (4.6) |

| MLP | 2.1 (0.2) | 2.6 (0.3) | 6.8 (1.1) | 7.7 (1.4) | 39.6 (5.1) | 39.3 (7.5) | 49.6 (5.3) | 52.7 (5.1) |

| LLP | 1.9 (0.2) | 2.8 (0.5) | 3.2 (0.5) | 2.6 (0.5) | 44.5 (6.1) | 36.9 (5.1) | 50.3 (5.2) | 52.8 (4.8) |

EFP, Early follicular phase; MFP, midfollicular phase; LFP, late follicular phase; ELP, early luteal phase; MLP, midluteal phase; LLP, late luteal phase.

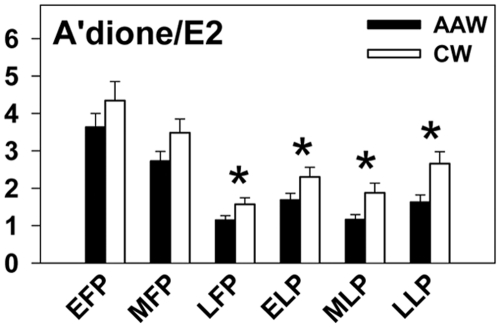

The a'dione to E2 ratio was significantly lower in AAW (P < 0.001), suggesting enhanced aromatase activity that was particularly evident in the late follicular and luteal phases (Fig. 3). A similar pattern of lower a'dione to E1 ratio in AAW was observed despite the availability of results in only half of the subjects (early follicular phase 0.02 ± 0.003 vs. 0.02 ± 0.003, P = 0.9 for AAW vs. CW, respectively; periovulatory phase 0.006 ± 0.0006 vs. 0.01 ± 0.003, P = 0.058; midluteal phase 0.007 ± 0.001 vs. 0.013 ± 0.003, P = 0.022). In contrast, there were no differences in the E1 to E2 ratio in the early follicular phase (1.8 ± 0.2 vs. 2.3 ± 0.4 in AAW vs. CW, P = 0.3), periovulatory phase (1.9 ± 0.2 vs. 2.4 ± 0.7, P = 0.5), or midluteal phase (1.7 ± 0.2 vs. 1.5 ± 0.2, P = 0.5), indicating similar 17βHSD1 activity in AAW and CW. The luteal phase P to a'dione ratio, a reflection of 17α-hydroxylase/17, 20-lyase activity, was also not different between AAW and CW in the early luteal (3.8 ± 0.4 vs. 2.8 ± 0.4, AAW vs. CW, P = 0.1), midluteal (7.3 ± 0.7 vs. 6.0 ± 0.9, P = 0.3), or late luteal phases (3.9 ± 0.6 vs. 2.6 ± 0.4, P = 0.1).

Fig. 3.

The a'dione to E2 ratio was lower in AAW compared with CW across the cycle (P = 0.01), consistent with increased aromatase activity in AAW. EFP, Early follicular phase; MFP, midfollicular phase; LFP, late follicular phase; ELP, early luteal phase; MLP, midluteal phase; LLP, late luteal phase. *, P < 0.001 for differences between AAW and CW in post hoc analyses.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that E2 levels are higher in reproductive aged AAW compared with CW. Measurement of E2 in daily blood samples across an entire menstrual cycle in age- and BMI-matched women in whom racial heritage is known for three generations resolves conflicting results from previous studies (7–16). The comprehensive design of this study has allowed us to further suggest that higher ovarian aromatase activity in AAW underlies their increase in serum E2.

In women, estrogen derives from both the ovary and from peripheral aromatization of ovarian or adrenal androgens to E1 in adipose tissue. Importantly, the contribution of adipose tissue E1 to serum E2 levels is known to be clinically insignificant in premenopausal women (30, 31), and any potential differences in peripheral aromatization are likely to be small because subjects were of similar BMI, none was obese, and AAW and CW of similar BMI demonstrate similar percent body fat (32, 33). Finally, the differences in E2 between AAW and CW remained significant after adjusting for BMI. Taken together, these data indicate that the ovary is the likely source of higher E2 levels in AAW in the current study.

Ovarian synthesis of E2 involves a series of enzymatic steps in both the theca and granulosa cells, which are subject to neuroendocrine and paracrine signaling. LH stimulates theca cell production of a'dione, which then diffuses into the granulosa cells. FSH drives aromatization of a'dione to E1, and E1 is then rapidly converted to E2 via 17β-HSDI (34). A'dione and E2 thus represent the predominant androgenic and estrogenic secretory products of the ovary, respectively (19, 35). It is unlikely that multiple folliculogenesis or variation in follicle size contributed to the differences in E2 because no CW or AAW developed more than a single dominant follicle, and the size of the dominant follicle did not differ between racial groups. There was no difference in the length of time between the final ultrasound and ovulation between the two groups or in the predicted maximum size of the dominant follicle. Although unlikely, we cannot exclude the possibility that racial differences in late follicular phase growth rates led us to underestimate the true size of the dominant follicle at ovulation in AAW. This is an important consideration because the paper by Kerin et al. (22) from which the late follicular growth rate of 2 mm/d is derived was based on a European cohort. There was also no difference in the prevalence of PCOM in AAW and CW in the current study. Although PCOM in nonhirsute, ovulatory women has been associated with a small but significant increase in ovarian androgen secretion (36), AAW and CW in the present study had similar rates of PCOM and similar levels of LH and a'dione. Of note, the prevalence of PCOM was relatively high in both AAW and CW, in line with results from recently reported population studies in which PCOM was assessed using the Rotterdam criteria (37, 38), as in the current study.

In addition to the increase in E2 in AAW compared with CW in the current study, there was a significant decrease in the a'dione to E2 ratio in AAW. The activity of enzymes involved in the early steps of E2 synthesis from cholesterol, as determined by substrate to product ratios, were similar in AAW and CW, and there was no racial difference in the absolute levels of a'dione, the major substrate for aromatase. The reduced ratios of a'dione to E2 and a'dione to E1 ratio in AAW compared with CW therefore point to increased activity or expression of ovarian aromatase in AAW. FSH is the primary regulator of ovarian aromatase, but FSH levels were not different between AAW and CW across the cycle. Furthermore, inhibin B, a biomarker of FSH activity (39), was not different between the groups. Taken together, these results therefore suggest that increased ovarian aromatase expression or activity in AAW compared with CW is not secondary to differences in follicle characteristics, FSH stimulation, or substrate availability.

A recent study of a multiracial cohort of women demonstrated significant racial differences in the frequency of several single nucleotide polymorphisms in the aromatase gene (CYP19) (40). There is also evidence to suggest racial differences in the concentrations of leptin and anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), which have been shown to influence ovarian aromatase activity. Leptin stimulates human granulosa cell aromatase activity in vitro (41), and African-American girls have higher leptin levels than Caucasian girls in studies that have controlled for pubertal stage and fat mass (42). In contrast, AMH inhibits human granulosa cell aromatase activity (43), and serum AMH levels are lower in age- and BMI-matched AAW compared with CW (44). Thus, leptin, AMH, or genetic variation in CYP19, may contribute to differences in aromatase activity in AAW and CW. Further studies in which aromatase expression and activity are more directly assessed, specifically controlling for follicle size (19, 34), will be necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Despite increased E2 levels in AAW, FSH and LH levels were not different, raising the question of whether the central feedback effects of E2 may be attenuated in AAW. However, there was an interaction between race and cycle phase in the current study such that E2 levels were not different in the early and midfollicular phases when E2 negative feedback on FSH is particularly relevant. In contrast, in the preovulatory period, E2 levels were significantly higher in AAW. Because positive feedback of E2 on LH is dose and time dependent, this difference might be expected to advance the timing or increase the amplitude of the preovulatory LH surge in AAW. Although there was a significant difference in the absolute E2 levels in the late follicular phase, there was no difference in the percent increase in E2 between cycle phases, raising the alternative hypothesis that E2 positive feedback may depend on the relative change in E2 rather than on the absolute value. Further studies will be necessary to distinguish between these two possibilities.

In summary, this study demonstrates that E2 levels are higher in ovulatory AAW compared with CW across the menstrual cycle and further suggests that these observations result from an increase in ovarian aromatase activity in AAW. Further studies will be needed to address this hypothesis more directly and to address possible effects of race on estrogen feedback dynamics. However, the findings from the current studies provide important insights into potential mechanisms underlying the health disparities in AAW and CW documented in epidemiological studies by suggesting that AAW may have a greater lifetime exposure to estrogens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HD 42708 and M01RR01066. N.D.S. received fellowship support from the National Institutes of Health (Grant 5T32 HD007396) and from the Scholars in Clinical Science program of Harvard Catalyst [The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (Award #UL1 RR 025758) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, the National Center for Research Resources, or the National Institutes of Health. This study was initiated before 1997 and was therefore not registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no conflicts relevant to this research.

Footnotes

- AAW

- African-American women

- a'dione

- androstenedione

- AMH

- anti-Mullerian hormone

- BMI

- body mass index

- CV

- coefficient of variation

- CW

- Caucasian women

- E1

- estrone

- E2

- estradiol

- 17βHSD1

- 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1

- P

- progesterone

- PCOM

- polycystic ovarian morphology.

References

- 1. Faerstein E, Szklo M, Rosenshein N. 2001. Risk factors for uterine leiomyoma: a practice-based case-control study. I. African-American heritage, reproductive history, body size, and smoking. Am J Epidemiol 153:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Cancer Society 2010. Breast cancer facts, figures, 2009–2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aloia JF. 2008. African Americans, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and osteoporosis: a paradox. Am J Clin Nutr 88:545S–550S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herman-Giddens ME, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, Bourdony CJ, Bhapkar MV, Koch GG, Hasemeier CM. 1997. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: a study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings network. Pediatrics 99:505–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Myrianthopoulos NC. 1970. An epidemiologic survey of twins in a large, prospectively studied population. Am J Hum Genet 22:611–629 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khoury MJ, Erickson JD. 1983. Maternal factors in dizygotic twinning: evidence from interracial crosses. Ann Hum Biol 10:409–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Woods MN, Barnett JB, Spiegelman D, Trail N, Hertzmark E, Longcope C, Gorbach SL. 1996. Hormone levels during dietary changes in premenopausal African-American women. J Natl Cancer Inst 88:1369–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pinheiro SP, Holmes MD, Pollak MN, Barbieri RL, Hankinson SE. 2005. Racial differences in premenopausal endogenous hormones. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14:2147–2153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haiman CA, Pike MC, Bernstein L, Jaque SV, Stanczyk FZ, Afghani A, Peters RK, Wan P, Shames L. 2002. Ethnic differences in ovulatory function in nulliparous women. Br J Cancer 86:367–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perry HM, III, Horowitz M, Morley JE, Fleming S, Jensen J, Caccione P, Miller DK, Kaiser FE, Sundarum M. 1996. Aging and bone metabolism in African American and Caucasian women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:1108–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lamon-Fava S, Barnett JB, Woods MN, McCormack C, McNamara JR, Schaefer EJ, Longcope C, Rosner B, Gorbach SL. 2005. Differences in serum sex hormone and plasma lipid levels in Caucasian and African-American premenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:4516–4520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Manson JM, Sammel MD, Freeman EW, Grisso JA. 2001. Racial differences in sex hormone levels in women approaching the transition to menopause. Fertil Steril 75:297–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mills PJ, Ziegler MG, Morrison TA. 1998. Leptin is related to epinephrine levels but not reproductive hormone levels in cycling African-American and Caucasian women. Life Sci 63:617–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Freedman RR, Girgis R. 2000. Effects of menstrual cycle and race on peripheral vascular alpha-adrenergic responsiveness. Hypertension 35:795–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ettinger B, Sidney S, Cummings SR, Libanati C, Bikle DD, Tekawa IS, Tolan K, Steiger P. 1997. Racial differences in bone density between young adult black and white subjects persist after adjustment for anthropometric, lifestyle, and biochemical differences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:429–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reutman SR, LeMasters GK, Kesner JS, Shukla R, Krieg EF, Jr, Knecht EA, Lockey JE. 2002. Urinary reproductive hormone level differences between African American and Caucasian women of reproductive age. Fertil Steril 78:383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feicht CB, Johnson TS, Martin BJ, Sparkes KE, Wagner WW., Jr 1978. Secondary amenorrhoea in athletes. Lancet 2:1145–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taylor AE, Whitney H, Hall JE, Martin K, Crowley WF., Jr 1995. Midcycle levels of sex steroids are sufficient to recreate the follicle-stimulating hormone but not the luteinizing hormone midcycle surge: evidence for the contribution of other ovarian factors to the surge in normal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:1541–1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McNatty KP, Makris A, DeGrazia C, Osathanondh R, Ryan KJ. 1979. The production of progesterone, androgens, and estrogens by granulosa cells, thecal tissue, and stromal tissue from human ovaries in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 49:687–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group 2004. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod 19:41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hall JE, Schoenfeld DA, Martin KA, Crowley WF., Jr 1992. Hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion and follicle-stimulating hormone dynamics during the luteal-follicular transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 74:600–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kerin JF, Edmonds DK, Warnes GM, Cox LW, Seamark RF, Matthews CD, Young GB, Baird DT. 1981. Morphological and functional relations of Graafian follicle growth to ovulation in women using ultrasonic, laparoscopic and biochemical measurements. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 88:81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Welt CK, Falorni A, Taylor AE, Martin KA, Hall JE. 2005. Selective theca cell dysfunction in autoimmune oophoritis results in multifollicular development, decreased estradiol, and elevated inhibin B levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:3069–3076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Welt CK, Jimenez Y, Sluss PM, Smith PC, Hall JE. 2006. Control of estradiol secretion in reproductive ageing. Hum Reprod 21:2189–2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taylor AE, Khoury RH, Crowley WF., Jr 1994. A comparison of 13 different immunometric assay kits for gonadotropins: implications for clinical investigation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 79:240–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Welt CK, Adams JM, Sluss PM, Hall JE. 1999. Inhibin A and inhibin B responses to gonadotropin withdrawal depends on stage of follicle development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:2163–2169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lambert-Messerlian GM, Hall JE, Sluss PM, Taylor AE, Martin KA, Groome NP, Crowley WF, Jr, Schneyer AL. 1994. Relatively low levels of dimeric inhibin circulate in men and women with polycystic ovarian syndrome using a specific two-site enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 79:45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Welt CK, McNicholl DJ, Taylor AE, Hall JE. 1999. Female reproductive aging is marked by decreased secretion of dimeric inhibin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Filicori M, Santoro N, Merriam GR, Crowley WF., Jr 1986. Characterization of the physiological pattern of episodic gonadotropin secretion throughout the human menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 62:1136–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zumoff B. 1981. Influence of obesity and malnutrition on the metabolism of some cancer-related hormones. Cancer Res 41:3805–3807 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bulun SE, Simpson ER. 1994. Competitive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis indicates that levels of aromatase cytochrome P450 transcripts in adipose tissue of buttocks, thighs, and abdomen of women increase with advancing age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78:428–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rahman M, Temple JR, Breitkopf CR, Berenson AB. 2009. Racial differences in body fat distribution among reproductive-aged women. Metabolism 58:1329–1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Heo M, Jebb SA, Murgatroyd PR, Sakamoto Y. 2000. Healthy percentage body fat ranges: an approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. Am J Clin Nutr 72:694–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Erickson GF, Shimasaki S. 2001. The physiology of folliculogenesis: the role of novel growth factors. Fertil Steril 76:943–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baird DT, Fraser IS. 1974. Blood production and ovarian secretion rates of estradiol-17β and estrone in women throughout the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 38:1009–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Adams JM, Taylor AE, Crowley WF, Jr, Hall JE. 2004. Polycystic ovarian morphology with regular ovulatory cycles: insights into the pathophysiology of polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:4343–4350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kristensen SL, Ramlau-Hansen CH, Ernst E, Olsen SF, Bonde JP, Vested A, Toft G. 2010. A very large proportion of young Danish women have polycystic ovaries: is a revision of the Rotterdam criteria needed? Hum Reprod 25:3117–3122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Duijkers IJ, Klipping C. 2010. Polycystic ovaries, as defined by the 2003 Rotterdam consensus criteria, are found to be very common in young healthy women. Gynecol Endocrinol 26:152–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Welt CK, Schneyer AL. 2001. Differential regulation of inhibin B and inhibin a by follicle-stimulating hormone and local growth factors in human granulosa cells from small antral follicles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:330–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sowers MR, Wilson AL, Kardia SR, Chu J, Ferrell R. 2006. Aromatase gene (CYP 19) polymorphisms and endogenous androgen concentrations in a multiracial/multiethnic, multisite study of women at midlife. Am J Med 119:S23–S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kitawaki J, Kusuki I, Koshiba H, Tsukamoto K, Honjo H. 1999. Leptin directly stimulates aromatase activity in human luteinized granulosa cells. Mol Hum Reprod 5:708–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wong WW, Nicolson M, Stuff JE, Butte NF, Ellis KJ, Hergenroeder AC, Hill RB, Smith EO. 1998. Serum leptin concentrations in Caucasian and African-American girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:3574–3577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grossman MP, Nakajima ST, Fallat ME, Siow Y. 2008. Mullerian-inhibiting substance inhibits cytochrome P450 aromatase activity in human granulosa lutein cell culture. Fertil Steril 89:1364–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Seifer DB, Golub ET, Lambert-Messerlian G, Benning L, Anastos K, Watts DH, Cohen MH, Karim R, Young MA, Minkoff H, Greenblatt RM. 2009. Variations in serum mullerian inhibiting substance between white, black, and Hispanic women. Fertil Steril 92:1674–1678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]