Abstract

Context:

Fetal growth restriction (FGR) due to placental dysfunction impacts short- and long-term neonatal outcomes. Abnormal umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry indicating elevated fetoplacental vascular resistance has been associated with fetal morbidity and mortality. Estrogen receptors are regulators of vasomotor tone, and fetoplacental endothelium expresses estrogen receptor-β (ESR2) as its sole estrogen receptor.

Objective:

Our objective was to elucidate the mechanism whereby ESR2 regulates placental villous endothelial cell prostanoid biosynthesis.

Design and Participants:

We conducted immunohistochemical analysis of human placental specimens and studies of primary fetoplacental endothelial cells isolated from subjects with uncomplicated pregnancies.

Main Outcome Measures:

We evaluated in vivo levels of ESR2 and cyclooxygenase-2 (PTGS2) in villous endothelial cells from fetuses with or without FGR and/or abnormal umbilical artery Doppler indices and in vitro effects of ESR2 on prostanoid biosynthetic gene expression.

Results:

ESR2 and PTGS2 expression were significantly higher within subjects with FGR with abnormal umbilical artery Doppler indices in comparison with controls (P < 0.01). ESR2 knockdown led to decreased cyclooxygenase-1 (PTGS1), PTGS2, prostaglandin F synthase (AKR1C3), and increased prostacyclin synthase (PTGIS), with opposing results found after ESR2 overexpression (P < 0.05). ESR2 mediates prostaglandin H2 substrate availability and, in the setting of differential regulation of AKR1C3 and PTGIS, altered the balance between vasodilatory and vasoconstricting prostanoid production.

Conclusions:

Higher ESR2 expression in the placental vasculature of FGR subjects with abnormal blood flow is associated with an endothelial cell phenotype that preferentially produces vasoconstrictive prostanoids. Endothelial ESR2 appears to be a master regulator of prostanoid biosynthesis and contributes to high-resistance fetoplacental blood flow, thereby increasing morbidity and mortality associated with FGR.

Fetal growth restriction (FGR) due to placental dysfunction continues to plague the field of obstetrics. To avert a stillbirth secondary to severe uteroplacental insufficiency, preterm delivery with its attendant consequences is often necessary. In contrast, gaining additional time in utero to minimize risks of prematurity carries substantial risks for stillbirth. This conundrum has been well illustrated by several clinical studies, including a randomized controlled trial showing that although stillbirths may be prevented by early delivery, the corresponding live births often result in neonatal demise, leading to a similar proportion of deaths (1, 2).

Beyond the perinatal hazards, FGR fetuses carry increased risks for developing adulthood diseases such as obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, insulin resistance, and renal insufficiency (3). Thus, an abnormal in utero environment has effects that reach far beyond that of the perinatal period and, in the long term, may set up a vicious cycle of metabolic derangements that continue to be propagated well into future pregnancies and generations (3, 4).

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying FGR are not well characterized. Most research efforts have focused on the maternal vascular compartment, and the fetoplacental circulation remains less studied. However, published literature strongly supports the close interrelationship of these two circulations, with the fetoplacental system playing a significant role in fetal growth and physiology. In ovine studies, reduction of uterine blood flow prevents normal decrements in umbilical vascular resistance with gestational age. This impairs oxygen and nutrient delivery and, ultimately, fetal growth (5). Similarly, decreases in fetoplacental blood flow by partial umbilical cord ligation diminish uterine artery blood flow (6). From a fetal standpoint, placental dysfunction is manifested by several alterations. First, umbilical venous flow decreases, affecting fetal cardiac preload (7). As placental dysfunction worsens, umbilical arterial pressure increases as reflected by abnormal umbilical artery Doppler indices. Together, the insult to fetal cardiac preload and afterload decrease oxygen transfer, causing redistribution of blood flow with preferential shunting to the myocardium and brain. Ultimately, critical vascular deterioration occurs, and in the absence of delivery, stillbirth almost always occurs. From a mechanistic perspective, cases of FGR demonstrate increased placental thromboxane A2 (TXA2) and decreased serum prostacyclin (PGI2) production (8, 9). This is confirmed by histopathological analyses that have found fetal stem vessel vasoconstriction, luminal obliteration, and wall thickening (10, 11).

Within vascular biology, several mechanisms exist to mediate vasomotor tone. However, the fetoplacental circulation is unique for several reasons. First, it lacks innervation and is not regulated by autonomic stimuli (12). Rather, humoral factors such as prostanoids play a vital role. Additionally, placental vessels respond to PGI2, TXA2, and prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) like other systemic vessels, but they also vasoconstrict when exposed to PGE2, which is a vasodilating substance in many other vascular beds (13). Lastly, although both estrogen receptor-α (ESR1) and estrogen receptor-β (ESR2) are typically expressed in vascular endothelium, the fetoplacental vascular bed is one of the few within the human body that expresses ESR2 as its sole estrogen receptor (14, 15). Thus, proposed mechanisms behind aberrant vascular tone in other systemic vessels cannot be directly translated to that of the fetoplacental circulation.

We have previously demonstrated that ESR2 mediates cyclooxygenase-2 (PTGS2) expression, and this occurs in the basal state in the absence of estradiol (E2) ligand (15). Beyond its regulation of PTGS2, the role of ESR2 in regulation of fetoplacental vasomotor tone remains unclear. Our objectives were to determine whether ESR2 is aberrantly expressed in documented cases of altered fetoplacental vasomotor tone and to further elucidate the role of ESR2 in fetoplacental endothelial cell prostanoid biosynthesis. We hypothesized that ESR2 mediates several aspects of prostanoid biosynthesis, where a pathologically altered ratio of vasodilating-to-vasoconstricting prostanoids may be the mechanism by which aberrant ESR2 expression contributes to the morbidity and mortality related to FGR.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Subjects for immunohistochemical analyses of ESR2 expression levels were identified through a database within the Department of Pathology. After identification, a retrospective chart review was performed to ensure the accuracy of the pathology database. Specifically, potential subjects were identified as FGR cases if both estimated and actual birth weight was less than 10th percentile for gestational age. Only cases that were able to demonstrate solid dating criteria as defined by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists were used. Cases were thereafter stratified into those with normal umbilical artery Doppler indices and those with abnormal waveforms (i.e. S/D ratio >95% for gestational age, absent, or reversed end-diastolic flow). Control subjects delivered infants weighing between the 10th and 90th percentile for gestational age, and they were matched to cases by gestational age within 7 d. Exclusion criteria for both cases and controls consisted of any hypertensive disease, diabetes, history of thrombosis, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, fetal anomaly, or fetal aneuploidy. In total, three groups were identified: 1) FGR with normal umbilical artery systolic/diastolic (S/D) ratio; 2) FGR with elevated S/D ratio, absent, or reversed end-diastolic flow; and 3) gestational age-matched controls.

Immunohistochemistry of placental specimens

Paraffin-embedded placental specimens from the three groups were obtained and processed by the Pathology Core Facility. They were incubated with primary antibody directed against ESR2 (rabbit host; Biogenix, Fremont, CA) or PTGS2 (rabbit host; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and diaminobenzidine substrate. Negative reagent controls were performed using rabbit IgG and the same secondary antibody and diaminobenzidine substrate. Slides were analyzed by a perinatal pathologist (L.E.) blinded to the outcomes, and immunoreactivity was quantified by a modified H-scoring system (16, 17). For ESR2, the H-scores were generated by adding together 2 × [percentage of strongly stained nuclei in ten ×40 fields] and 1 × [percentage of weakly stained nuclei in ten ×40 fields], yielding scores from 0–200. PTGS2 H-scores were generated by adding together 3 × [percentage of strongly stained cytoplasm in ten ×60 fields], 2 × [percentage of weak, diffusely positive cytoplasm in ten ×60 fields], and 1 × [percentage or weak, focally positive cytoplasm in ten ×60 fields], yielding scores from 0–300. Magnification of ×60 was used for PTGS2 analysis to improve accuracy in evaluation of cytoplasmic staining in fetal endothelial cells, because they generally have more scanty cytoplasm than surrounding smooth muscle cells or connective tissue.

Cellular isolation and culture

Human placental villous endothelial cell isolation was performed as previously described with approval by the Institutional Review Board at Northwestern University. Cells were isolated from placentas from uncomplicated, full-term pregnancies immediately after delivery. Immunofluorescence confirmed purity of the cells (data not shown), and primary cells were cultured up to the fifth passage to avoid changes in phenotype (14, 18). Cells were cultured and treated using phenol red-free medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, bovine brain extract, epidermal growth factor, hydrocortisone, and gentamicin/amphotericin B (Lonza, Walkersville, MD).

Cell treatments

Before treatments, cells were starved in serum-free medium overnight. Treatments included vehicle (ethyl alcohol 1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), E2 (10−11 to 10−6 m; Sigma-Aldrich), the ESR2-specific agonist diarylpropionitrile (DPN; 10−11 to 10−6 m; Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO), lipopolysaccharide (LPS; from Escherichia coli 026:B6; 100 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), or PGH2 (10−6 m; Cayman Chemical).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA from primary endothelial cell cultures was extracted with Tri-Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed using Q-script (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD). Specific oligodeoxynucleotide primers were synthesized according to published information for cDNA of the various genes (PTGS1, forward CAATGAGTACCGCAAGAGGTTTG and reverse CAACTCTGCTGCCATCTCCTT; PTGS2, forward GAATCATTTGAAGAACTTACAGGAG and reverse GAGGCTTTTCTACCAGAAGG; PTGIS, forward CCGTGGCTCCCTGTCAGT and reverse GCAGCTTCCACAGGCGAC; TBXAS1, forward GGAGTTCAAGTCGGTAGC and reverse GTCCCCAGATTCCGCATAG; PTGES2, forward AGAAGCCGAATCTCGCTGATTTGG and reverse GGACAAGGGGCAGAATGAT; AKR1C3, forward CCATTGGGGTGTCAAACTTC and reverse CCGGTTGAAATACGGATGAC) (15). Each primer set spanned two exons. Primer sets for the constitutively expressed 36B4 housekeeping gene was also used as described in previous reports (19).

Real-time quantitative PCR was used to determine the relative amounts of each transcript using the DNA-binding dye SYBR green (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and the ABI Prism 7900 HT Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Cycling conditions started at 50 C for 2 min followed by 95 C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of 95 C for 15 sec and 60 C for 1 min. The cycle threshold (Ct) was placed at a set level where the exponential increase in PCR amplification was approximately parallel between all samples. Relative fold change was calculated by comparing Ct values between the target gene and 36B4 as the reference guide. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to analyze these relative changes in gene expression (20).

Protein isolation and immunoblotting

Placental endothelial cells were lysed using mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER; Pierce, Rockford, IL) and 1× protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein concentrations were determined by colorimetric bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce), and equal concentrations of total protein were loaded in each well. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were probed using antibodies against β-actin (ACTB), ESR2, cyclooxygenase-1 (PTGS1), PTGS2, prostacyclin synthase (PTGIS), PGE synthase (PTGES2), and PGF synthase (AKR1C3). Antirabbit and antimouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) were used as secondary antibodies. Lastly, immunoreactive bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

RNA interference

Two distinct RNA oligonucleotides directed against ESR2 and a mismatch negative control small interfering RNA (siRNA) were purchased from Invitrogen. Placental endothelial cells were cultured in medium lacking antibiotics. On the day of transfection, the RNAiMAX lipofectamine-based reagent was combined in conjunction with 100 nm siRNA duplexes diluted in Opti-Mem I (Invitrogen) and applied to the cells according to the manufacturer's instructions. Six hours after the start of the transfection, the medium was changed to complete growth medium without antibiotics, and cells were allowed to recover overnight. Cells were maintained for 48 and 72 h for isolation of RNA and protein, respectively. Cells undergoing supernatant analysis via ELISA were maintained in growth medium for 48 h. They were then starved overnight in serum-free medium lacking antibiotics and then treated with vehicle or 10−6 m PGH2 for the next 8 h.

ESR2 overexpression

Transfections were performed using a plasmid pRST7-ESR2 (Addgene Inc., Cambridge, MA) containing the human ESR2 gene that was described previously or control plasmid vector. Both control and pRST7-ESR2 plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing before transfection. DNA (10 μg) was introduced into the cells using Lipofectin (Invitrogen) with a ratio of 1:4 (plasmid DNA to transfection reagent). Cells were collected and processed for mRNA and protein at 48 and 72 h, respectively.

Prostanoid enzyme immunoassays

Villous endothelial cells were subjected to ESR2 RNA interference. Cells were serum- and supplement-starved in basal media overnight at 36 h from the start of transfection. The medium was replaced the next morning. Twenty-four hours later, cell culture supernatant was collected. Enzyme immunoassays were performed for 6-keto PGF1α (main metabolite of PGI2), thromboxane B2 (main metabolite of TXA2), PGE2, and PGF2α with commercial kits that used competitive substrate-acetylcholinesterase assays (Cayman). Concentrations were normalized to total protein concentrations.

For studies with PGH2 treatment after ESR2 knock-down, cells were starved overnight at 50 h from the start of transfection. The medium was replaced the following morning, and cells were either treated with vehicle or PGH2 for the next 8 h, with cell culture supernatant collected at approximately 72 h from the start of transfection. Enzyme immunoassays were performed for 6-keto PGF1α and PGF2α.

Prostaglandin H synthase (cyclooxygenase) activity assay

Cells underwent transfection with control siRNA or ESR2 siRNA oligo. After 48 h, cells were trypsinized and counted, with 2 × 106 cells aliquoted per time point reaction. Cells were resuspended in potassium phosphate (50 mm, pH 7.4) plus EDTA (2 mm) buffer and sonicated, and the homogenate was then incubated for 1 h with [3H]arachidonic acid ([3H]AA; approximately 5000 cpm/ml) along with 4.2 mm l-tryptophan and 1.75 μm hematin. Incubations were also conducted in the presence of 1 mm phenol, a cosubstrate of peroxidase, to trap PGH2 as the major reaction product. Three aliquots were taken at time zero and again at 20, 40, and 80 min after the 1-h incubation. Unconjugated steroids were extracted with ethyl acetate (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The organic phase was evaporated and redissolved in methanol. After adding 100 μg carrier AA and PGH2, the samples were reevaporated, redissolved in methanol, and plated on silica gel thin-layer plates (0.125 mm) containing fluorescent indicator (UV254) (Sigma-Aldrich). Plates were placed in a solvent system with ethyl acetate/2,2,4-trimethylpentane/acetic acid/water (55:25:10:50, vol/vol) to separate and identify AA and PGH2. The UV-absorbing AA and PGH2 were identified, and these areas were marked accordingly. The silica gels containing the indicated prostanoids were transferred to counting vials. Liquid scintillation fluid (MP, Irvine, CA) was added. 3H was counted, and percent conversion of [3H]AA to [3H]PGH2 was calculated.

Statistical analysis

An a priori power calculation was performed for three groups before immunohistochemical analysis of ESR2, demonstrating that at least 16 samples in each group were required for 90% power (α = 0.05, two-tailed) to detect a maximum difference of 30 in H-score among the three groups (assumed sd of 23). To provide safe margins, we studied 20 samples in each group. After collection of the data, the Shapiro-Wilk test to assess for normality was performed.

All cellular experiments were performed on at least three representative subject samples, with each repeated in triplicate, using cells between the first and fifth passage. Each illustrated experiment was performed using cells from a single subject with the results reproduced in at least two other subject samples. Numerical data are reported as means of the three replicates performed within one subject, with error bars representing sem. Statistical analysis for comparison of treatment groups was performed using Student's t test or one-way ANOVA with Scheffé adjustment for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

ESR2 expression is higher in villous endothelial cells of pregnancies complicated by FGR with abnormal fetoplacental blood flow

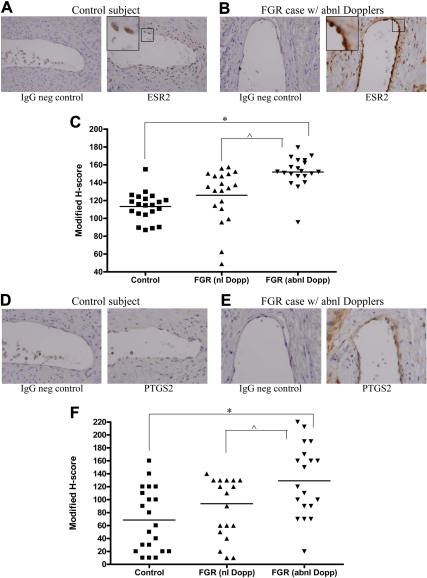

We compared modified H-score staining intensity of ESR2 in villous endothelial cells in three groups of subjects: 1) controls, 2) FGR with normal umbilical artery S/D ratio, and 3) FGR with abnormal umbilical artery Doppler indices. Statistical testing demonstrated an essentially normal distribution of modified H-score values (P = 0.07). Immunohistochemical analyses of ESR2 expression demonstrated a statistically significant increase in ESR2 expression within endothelial cells of stem villous vessels of group 3 in comparison with group 1 using one-way ANOVA (Fig. 1, A–C). We had oversampled beyond the initial sample size estimate to provide safe margins. This yielded a sd that was larger than anticipated, but with the oversampling, there was ultimately 89.9% power to detect a difference of 30 in modified H-score. Of note, although there appeared to be a trend toward higher ESR2 expression in group 3 compared with group 2, the difference did not reach statistical significance.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of ESR2 and PTGS2 expression in endothelial cells of villous stem vessels. A and B, Negative (neg) serum control (left) and nuclear ESR2 immunohistochemistry (right) in a control subject (A) compared with negative serum control (left) and nuclear ESR2 staining (right) in a FGR case with abnormal umbilical artery Doppler indices (B); C, graphical representation of modified H-scoring for all cases and their gestational age-matched controls (*, P < 0.05; ^, P = 0.09); D and E, negative serum control (left) and cytoplasmic PTGS2 immunohistochemistry (right) in a control subject (D) compared with negative serum control (left) and cytoplasmic PTGS2 staining (right) in a FGR case with abnormal umbilical artery Doppler indices (D); F, graphical representation of modified H-scoring for all cases and their gestational age-matched controls. ESR2 images were captured at ×40 magnification, while PTGS2 images were captured at ×60 magnification. (*, P < 0.05; ^, P = 0.09) abnl, Abnormal; Dopp, Doppler; neg, negative; nl, normal.

Similar to ESR2, PTGS2 expression is higher in villous endothelial cells of pregnancies complicated by FGR with abnormal fetoplacental blood flow

We have previously demonstrated that ESR2 ablation via RNA interference resulted in a decrease in PTGS2 expression (15). To determine whether these findings were correlated to in vivo data, we also compared modified H-score staining intensity of PTGS2 in villous endothelial cells in the same three groups of subjects as noted above. Shapiro-Wilks testing demonstrated normality of these H-scores as well (P = 0.063). Using one-way ANOVA, PTGS2 expression was statistically significantly higher within endothelial cells of stem villous vessels of group 3 in comparison with group 1 (Fig. 1, D–F). Similar to ESR2 results, there appeared to be a trend toward a difference between the FGR group with normal Doppler indices and the FGR group with abnormal Dopplers, although this was not statistically significant.

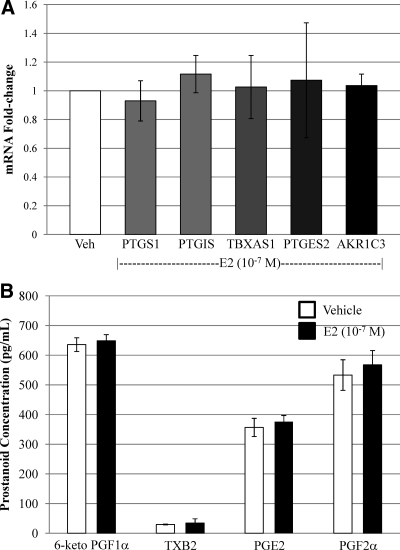

E2 and DPN do not induce prostanoid biosynthetic genes

Previous studies have demonstrated E2 induction of prostanoid biosynthetic genes within vascular endothelium of certain organs (21–26). Within our fetoplacental endothelial cell model, however, we previously demonstrated lack of effect of E2 or DPN on PTGS2 induction (15). In contrast, PTGS2 was inducible when cells were exposed to LPS (15). Similar to our PTGS results, there was no induction of PTGS1, PTGIS, thromboxane synthase (TBXAS1), PTGES2, or AKR1C3 mRNA expression with E2 treatment (Fig. 2A) or DPN (data not shown). Additionally, there was no difference in downstream prostanoid production (Fig. 2B). This occurred regardless of dose of E2 (10−11 to 10−6 m) or duration of treatment (1, 4, 8, and 24 h) (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

E2 does not induce prostanoid biosynthetic gene expression and activity in fetoplacental endothelial cells. A, Treatment with E2 did not induce PTGS1, PTGIS, TBXAS1, PTGES2, or AKR1C3; B, similarly, prostanoid levels were not altered by exposure to E2. Veh, Vehicle.

ESR2 mediates prostanoid biosynthetic gene expression

In the absence of estrogenic stimulation of prostanoid synthesis, we questioned the role of ESR2 within fetoplacental endothelium. We had previously demonstrated ESR2 regulation of PTGS2 expression and activity that occurred independent of E2 ligand presence (15). Thus, we investigated whether ESR2 mediated other prostanoid biosynthetic genes in a similar fashion. ESR2 RNA interference ablated ESR2 mRNA and protein expression. Regardless of presence (data not shown) or absence of ligand, this led to decreases in PTGS1, PTGS2, and AKR1C3 gene expression while increasing PTGIS gene expression (Fig. 3). There was no effect of ESR2 knockdown on PTGES2 and TBXAS1 expression. Similar effects were noted when a second ESR2 siRNA oligonucleotide was used to rule out potential off-target effects of our primary ESR2 siRNA (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://jcem.endojournals.org). In contrast, ESR2 overexpression demonstrated up-regulated PTGS1, PTGS2, and AKR1C3 expression while decreasing PTGIS expression (Fig. 4). Again, the presence of E2 did not alter these findings (data not shown). Of note, treatment with either ICI 182,780, a nonspecific estrogen receptor antagonist, or 4-[2-phenyl-5,7-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl] phenol (PHTPP), an ESR2-specific antagonist did not alter prostanoid biosynthetic gene expression (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fig. 3.

ESR2 RNA interference leads to regulation of various prostanoid biosynthetic genes. A, Real-time PCR graph demonstrating that ESR2 mRNA is approximately 90% ablated after transfection with ESR2 siRNA in comparison with that transfected with control, mismatched siRNA. In the setting of ESR2 ablation, PTGS1, PTGS2, and AKR1C3 expression levels are significantly decreased. In contrast, PTGIS is significantly increased (*, P < 0.005; ^, P = 0.01; #, P < 0.05). B, Representative Western blot demonstrating effects of ESR2 knockdown. C, Graphical representation of combined Western blots confirming change in protein expression of PTGS1, PTGS2, PTGIS, and AKR1C3 after ESR2 RNA interference transfection (*, P < 0.01 when comparing expression after ESR2 knockdown and control siRNA transfection).

Fig. 4.

ESR2 RNA overexpression also regulates various prostanoid biosynthetic genes. A, ESR2 overexpression led to increases in PTGS1, PTGS2, and AKR1C3 mRNA levels while decreasing PTGIS expression (*, P < 0.05); B, representative Western blot demonstrating effects of ESR2 overexpression; C, graphical representation of combined Western blots confirming change in protein expression of PTGS1, PTGS2, PTGIS, and AKR1C3 after ESR2 overexpression (*, P < 0.001; ^, P < 0.05, ESR2 overexpression in comparison with transfection with empty vector).

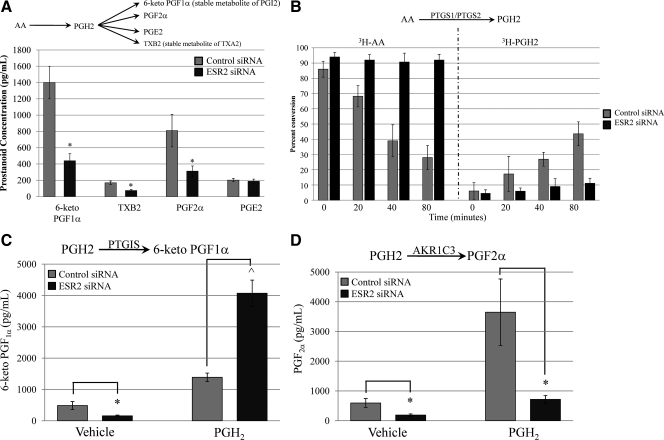

ESR2 knockdown results in decreases in 6-keto PGF1α, TXB2, and PGF2α

To illustrate the effects of ESR2 knockdown on actual prostanoid biosynthesis, enzyme immunoassays for the terminal prostanoids were performed. In comparison with control siRNA transfection, ESR2 ablation led to decreases in 6-keto PGF1α, TXB2, and PGF2α concentrations (Fig. 5A). There was no effect on PGE2 levels.

Fig. 5.

A, Effects of ESR2 RNA interference on endothelial cell prostanoid production. ESR2 knock-down led to decreases in 6-keto PGF1α (stable metabolite of PGI2), TXB2 (stable metabolite of TXA2), and PGF2α (*, P < 0.05). There were no changes noted in PGE2 concentrations. B, Thin-layer chromatography measuring the effects of ESR2 ablation on COX activity. With control siRNA transfection, 3H-AA levels decreased (gray bars, left) as 3H-PGH2 increased (gray bars, right). In contrast, with ESR2 knockdown, there was minimal conversion of 3H-AA to 3H-PGH2 (black bars). C, With ESR2 knockdown, 6-keto PGF1α levels decreased as expected. When PGH2 was added to bypass the effects of ESR2 on COX activity and PGH2 substrate availability, 6-keto PGF1α levels increased significantly. D, ESR2 knockdown in the absence of PGH2 leads to a decrease in PGF2α. Despite additional PGH2 substrate, PGF2α levels remain decreased after ESR2 RNA interference (*, P < 0.02; ^, P < 0.001).

Cyclooxygenase (PTGS) activity assays confirm that ESR2 affects PGH2 substrate availability

Because ESR2 knockdown up-regulated PTGIS gene expression, we anticipated an increase in 6-keto PGF1α concentrations. However, the decrease that we ultimately observed might have been explained by an ESR2 effect on PTGS1, PTGS2, and thereby, PGH2 substrate availability. Thus, we performed PTGS activity assays using tritiated arachidonic acid ([3H]AA) and phenol, a peroxidase cosubstrate that maintains PGH2 as the major reaction product. We performed thin-layer chromatography to measure [3H]AA conversion to [3H]PGH2. In the setting of control siRNA transfection, [3H]AA decreased over time as [3H]PGH2 increased (Fig. 5B). However, when ESR2 was ablated, [3H]AA and [3H]PGH2 remained relatively stable (Fig. 5B), confirming that ESR2 is affecting PTGS1 and PTGS2 activity and, thereby, PGH2 availability.

ESR2 directly regulates PTGIS and AKR1C3

To bypass effects of ESR2 on PGH2 availability and to directly assess effects of ESR2 on PTGIS and AKR1C3, exogenous PGH2 was added. With ESR2 knockdown and vehicle treatment, 6-keto PGF1α concentrations decreased as previously noted. However, when PGH2 availability was unhindered, ESR2 knockdown led to a significant increase in 6-keto PGF1α (Fig. 5C). In contrast, PGF2α levels remained suppressed despite addition of PGH2 in the setting of ESR2 knockdown (Fig. 5D). In total, this suggests that ESR2 directly mediates PTGIS and AKR1C3 expression in opposing directions.

Discussion

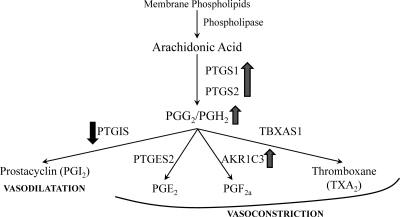

We demonstrated higher ESR2 expression within the villous endothelium of FGR pregnancies with abnormal fetoplacental blood flow in comparison with gestational age-matched controls. Using primarily isolated fetoplacental endothelial cells from full-term, uncomplicated pregnancies, we showed that ESR2 regulates PTGS1, PTGS2, PTGIS, and AKR1C3. We also demonstrated higher stem vessel endothelial PTGS2 expression in vivo in pregnancies complicated by FGR with abnormal umbilical artery Doppler indices compared with appropriately grown controls. In total, this suggests that high ESR2 expression in FGR leads to increased PTGS1, PTGS2, and thereby PGH2 availability. Because PTGIS is down-regulated in this case, available PGH2 is shunted toward production of vasoconstricting prostanoids (Fig. 6). This is further augmented by ESR2 up-regulation of AKR1C3. In total, elevated ESR2 expression in endothelium of FGR pregnancies with abnormal blood flow may be a primary abnormality promoting vasoconstriction and not a compensatory mechanism to aberrant maternal compartment function as originally hypothesized.

Fig. 6.

Proposed summary pathway. Higher ESR2 expression within fetoplacental endothelium of FGR fetuses with abnormal blood flow leads to an ESR2-mediated increase in PTGS1 and PTGS2. This increases PGH2 substrate availability. Because PTGIS expression is decreased in the setting of higher ESR2 expression, this increase in PGH2 substrate is shunted toward terminal synthases that produce prostanoids that lead to vasoconstriction of the fetoplacental vascular bed. Furthermore, the up-regulation of AKR1C3 further contributes to vasoconstrictive prostanoid biosynthesis.

These findings are unique for several reasons. First, this is the only report to our knowledge that details a mechanism underlying regulation of human fetoplacental vascular prostanoid biosynthesis. This is important because fetoplacental vessels do not respond to autonomic stimuli but, rather, solely to humoral factors such as prostanoids (12, 13). Second, because this vasculature uniquely vasoconstricts when exposed to PGE2, the down-regulatory effect of ESR2 on PTGIS is even more striking. Third, the placenta is one of the few organs to contain endothelial cells that solely express ESR2 of the two estrogen receptors, and this likely plays into its unique phenotype. Finally, our findings of ESR2 regulation of PTGS1, PTGS2, AKR1C3, and PTGIS were found regardless of the presence or absence of ligand.

In general vascular physiology, both ESR1 and ESR2, are key mediators (27–29). However, ESR2 appears to play a distinct role. For instance, ESR2 knockout mice demonstrate significant systolic and diastolic hypertension (30). Although these findings seem to contradict those within our cell model system, the species, organ specificity, and estrogen receptor expression profile differ, with mice expressing both ESR1 and ESR2 within their vasculature. In fact, others have found that certain ESR2 polymorphisms are associated with preclinical atherosclerosis in early adulthood (31). Similarly, ESR2 is higher in vessels that have sustained vascular luminal injury, and within human coronary arteries, increased ESR2 expression is linked to advanced atherosclerosis and calcification independent of age or hormone status (32, 33). Together, these results not only confirm the importance of ESR2 in vascular biology but also highlight its multifaceted and complex role.

Our findings of ligand-independent ESR2 regulation of PTGS1, PTGS2, AKR1C3, and PTGIS also warrant further discussion. Although we have demonstrated that neither E2 nor DPN affected prostanoid biosynthetic gene expression, others have demonstrated E2 effects on PTGS1, PTGS2, PTGIS, and TBXAS1 within other endothelial cells (21–23, 26). This suggested potential confounders within our model. First, we considered the possibility that these genes were not inducible within our model. However, we were able to demonstrate induction using LPS (15). We then reflected upon the high expression of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (HSD17B2) within these cells. Because HSD17B2 efficiently converts E2 to its less biologically active form estrone, it was possible that HSD17B2 was metabolizing the exogenously administered E2. However, we did not find any support that DPN was able to be enzymatically deactivated by HSD17B2. Finally, because other endothelial cells have been shown to express aromatase, we tested ours for aromatase expression. Using a validated aromatase primer-probe, Ct values were undetectable within our cell type, making it unlikely that endogenous E2 production was masking prostanoid biosynthesis. Finally, neither ICI 182,780 nor PHTPP, two estrogen receptor antagonists, altered prostanoid biosynthetic gene expression. Together, these results further suggested ligand-independent effects of ESR2 on fetoplacental prostanoid biosynthesis.

Transcriptional activation of a gene requires several steps: ligand binding, dimerization, interaction with cofactors, and DNA binding. However, lack of E2 or DPN effect suggests that mechanisms other than ligand binding need to be explored. For example, phosphorylation of specific sites on either estrogen receptor is one mechanism by which ligand-independent effects occur (34). Phosphorylation of estrogen receptor-associated cofactors also regulate protein stability, DNA binding, and protein-protein interactions (35). Ligand-independent activation of ESR1 leads to up-regulation of TNF-α through the stimulatory actions of c-jun, nuclear factor-κB, and CREB-binding protein (36). With regard to ESR2, phosphorylation of the activation function-1 (AF-1) domain of ESR2 by MAPK leads to recruitment of steroid receptor coactivator-1 in the absence of ligand (37, 38). In fact, investigators have found that cellular levels of ESR2 were able to be regulated through phosphorylation of activation function-1 by affecting ubiquitination (39). Finally, a recent publication illustrated that unliganded ESR2 is recruited to the promoter of two tumor suppressor genes (40). In total, the concept of ligand-independent regulation of prostanoid biosynthesis by ESR2 is not implausible.

Limitations of our study include potential confounders of gestational age and indication for preterm delivery within the control population chosen for immunohistochemical analyses. There are no data, to our knowledge, regarding ESR2 expression in placenta as gestation progresses. However, analyses of our control and case populations individually did not suggest that there was a gestational age-dependent change in ESR2 expression. Additionally, we acknowledge that preterm births secondary to spontaneous preterm delivery is not a perfectly analogous control population. However, we used specimens from these subjects because placental vascular resistance normally decreases with advancing gestational age, and this was considered to be a bigger confounder in assessing fetoplacental endothelial cell prostanoid biosynthesis than the various potential pathways that may lead to the end result of spontaneous preterm birth. We attempted to minimize any biasing effects by ensuring that none of the control specimens demonstrated inflammation within the fetoplacental vascular compartment, as determined by our perinatal pathologist. We also chose control subjects that underwent preterm birth secondary to a bleeding placenta previa to include controls that did not experience labor. Other limitations include the use an in vitro primary cell culture model, which precludes investigation of the effects of trophoblast-endothelial cell and vascular smooth muscle cell-endothelial cell interactions.

In conclusion, ESR2 expression is higher in stem villous vessel endothelial cells in placentas complicated by FGR with abnormal umbilical artery Doppler indices in comparison with controls. This appears to be a primary aberration, leading to increased PTGS1 and PTGS2 expression and increased PGH2 substrate. In turn, secondary to down-regulation of PTGIS by ESR2, this PGH2 substrate is shunted toward the remaining terminal synthases, resulting in a vasoconstrictive prostanoid profile. Much remains unknown regarding placental function and pregnancy outcome. In light of the significant short- and long-term consequences of placental dysfunction, however, this is a critical area of research that warrants further in-depth study. Future research detailing the mechanism by which ESR2 expression is increased in FGR with abnormal Doppler indices and further elucidation of the role of ligand-independent regulation of ESR2 will be critical components in our understanding of normal and aberrant placental function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the nurses, fellows, residents, and faculty at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and to all women who participated in the study.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant K08-HD HD 061654 (to E.J.S.), American Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Foundation/Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Scholarship (to E.J.S.), and Eleanor Wood Prince Grant Initiative: A Project of the Woman's Board of Northwestern Memorial Hospital (to: E.J.S.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AA

- Arachidonic acid

- AKR1C3

- PGF synthase

- Ct

- cycle threshold

- DPN

- diarylpropionitrile

- E2

- estradiol

- ESR1

- estrogen receptor-α

- ESR2

- estrogen receptor-β

- FGR

- fetal growth restriction

- HSD17B2

- 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- PGF2α

- prostaglandin F2α

- PGI2

- prostacyclin

- PTGIS

- prostacyclin synthase

- PTGES2

- PGE synthase

- PTGS1

- cyclooxygenase-1

- PTGS2

- cyclooxygenase-2

- S/D

- systolic/diastolic

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- TBXAS1

- thromboxane synthase

- TXA2

- placental thromboxane A2.

References

- 1. GRIT Study Group 2003. A randomised trial of timed delivery for the compromised preterm fetus: short term outcomes and Bayesian interpretation. BJOG 110:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thornton JG, Hornbuckle J, Vail A, Spiegelhalter DJ, Levene M. 2004. Infant wellbeing at 2 years of age in the Growth Restriction Intervention Trial (GRIT): multicentred randomised controlled trial. Lancet 364:513–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Simmons RA. 2009. Developmental origins of adult disease. Pediatr Clin North Am 56:449–466, Table of Contents [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holt RI, Byrne CD. 2002. Intrauterine growth, the vascular system, and the metabolic syndrome. Semin Vasc Med 2:33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rankin JH, Goodman A, Phernetton T. 1975. Local regulation of the uterine blood flow by the umbilical circulation. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 150:690–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stock MK, Anderson DF, Phernetton TM, McLaughlin MK, Rankin JH. 1980. Vascular response of the fetal placenta to local occlusion of the maternal placental vasculature. J Dev Physiol 2:339–346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neerhof MG, Thaete LG. 2008. The fetal response to chronic placental insufficiency. Semin Perinatol 32:201–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sorem KA, Siler-Khodr TM. 1995. Placental prostanoid release in severe intrauterine growth retardation. Placenta 16:503–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stuart MJ, Clark DA, Sunderji SG, Allen JB, Yambo T, Elrad H, Slott JH. 1981. Decrease prostacyclin production: a characteristic of chronic placental insufficiency syndromes. Lancet 1:1126–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sebire NJ, Sepulveda W. 2008. Correlation of placental pathology with prenatal ultrasound findings. J Clin Pathol 61:1276–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sebire NJ, Talbert D. 2001. ‘Cor placentale’: placental intervillus/intravillus blood flow mismatch is the pathophysiological mechanism in severe intrauterine growth restriction due to uteroplacental disease. Med Hypotheses 57:354–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Poston L. 1997. The control of blood flow to the placenta. Exp Physiol 82:377–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Poston L, McCarthy AL, Ritter JM. 1995. Control of vascular resistance in the maternal and feto-placental arterial beds. Pharmacol Ther 65:215–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Su EJ, Cheng YH, Chatterton RT, Lin ZH, Yin P, Reierstad S, Innes J, Bulun SE. 2007. Regulation of 17-βhydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 in human placental endothelial cells. Biol Reprod 77:517–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Su EJ, Lin ZH, Zeine R, Yin P, Reierstad S, Innes JE, Bulun SE. 2009. Estrogen receptor-β mediates cyclooxygenase-2 expression and vascular prostanoid levels in human placental villous endothelial cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200:427.e1–e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gurates B, Sebastian S, Yang S, Zhou J, Tamura M, Fang Z, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Bulun SE. 2002. WT1 and DAX-1 inhibit aromatase P450 expression in human endometrial and endometriotic stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:4369–4377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCarty KS, Jr, Miller LS, Cox EB, Konrath J, McCarty KS., Sr 1985. Estrogen receptor analyses. Correlation of biochemical and immunohistochemical methods using monoclonal antireceptor antibodies. Arch Pathol Lab Med 109:716–721 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lang I, Pabst MA, Hiden U, Blaschitz A, Dohr G, Hahn T, Desoye G. 2003. Heterogeneity of microvascular endothelial cells isolated from human term placenta and macrovascular umbilical vein endothelial cells. Eur J Cell Biol 82:163–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frasor J, Stossi F, Danes JM, Komm B, Lyttle CR, Katzenellenbogen BS. 2004. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: discrimination of agonistic versus antagonistic activities by gene expression profiling in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 64:1522–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Akarasereenont P, Techatraisak K, Thaworn A, Chotewuttakorn S. 2000. The induction of cyclooxygenase-2 by 17β-estradiol in endothelial cells is mediated through protein kinase C. Inflamm Res 49:460–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gibson LL, Hahner L, Osborne-Lawrence S, German Z, Wu KK, Chambliss KL, Shaul PW. 2005. Molecular basis of estrogen-induced cyclooxygenase type 1 upregulation in endothelial cells. Circ Res 96:518–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li M, Kuo L, Stallone JN. 2008. Estrogen potentiates constrictor prostanoid function in female rat aorta by upregulation of cyclooxygenase-2 and thromboxane pathway expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294:H2444–H2455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Myers SI, Turnage RH, Bartula L, Kalley B, Meng Y. 1996. Estrogen increases male rat aortic endothelial cell (RAEC) PGI2 release. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 54:403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ospina JA, Krause DN, Duckles SP. 2002. 17β-Estradiol increases rat cerebrovascular prostacyclin synthesis by elevating cyclooxygenase-1 and prostacyclin synthase. Stroke 33:600–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tamura M, Deb S, Sebastian S, Okamura K, Bulun SE. 2004. Estrogen up-regulates cyclooxygenase-2 via estrogen receptor in human uterine microvascular endothelial cells. Fertil Steril 81:1351–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mendelsohn ME. 2000. Mechanisms of estrogen action in the cardiovascular system. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 74:337–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mendelsohn ME. 2002. Genomic and nongenomic effects of estrogen in the vasculature. Am J Cardiol 90:3F–6F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. 1999. The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med 340:1801–1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhu Y, Bian Z, Lu P, Karas RH, Bao L, Cox D, Hodgin J, Shaul PW, Thoren P, Smithies O, Gustafsson JA, Mendelsohn ME. 2002. Abnormal vascular function and hypertension in mice deficient in estrogen receptor β. Science 295:505–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nikkari ST, Henttonen A, Kunnas T, Kähönen M, Hutri-Kähönen N, Juonala M, Marniemi J, Viikari J, Raitakari OT, Lehtimäki T. 2008. Estrogen receptor 2 polymorphism and carotid intima-media thickness. Genet Test 12:537–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cruz MN, Agewall S, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Kublickiene K. 2008. Acute dilatation to phytoestrogens and estrogen receptor subtypes expression in small arteries from women with coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis 196:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lindner V, Kim SK, Karas RH, Kuiper GG, Gustafsson JA, Mendelsohn ME. 1998. Increased expression of estrogen receptor-β mRNA in male blood vessels after vascular injury. Circ Res 83:224–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sanchez M, Picard N, Sauvé K, Tremblay A. 2010. Challenging estrogen receptor β with phosphorylation. Trends Endocrinol Metab 21:104–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ward RD, Weigel NL. 2009. Steroid receptor phosphorylation: assigning function to site-specific phosphorylation. Biofactors 35:528–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cvoro A, Tzagarakis-Foster C, Tatomer D, Paruthiyil S, Fox MS, Leitman DC. 2006. Distinct roles of unliganded and liganded estrogen receptors in transcriptional repression. Mol Cell 21:555–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tremblay A, Giguère V. 2001. Contribution of steroid receptor coactivator-1 and CREB binding protein in ligand-independent activity of estrogen receptor β. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 77:19–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tremblay A, Tremblay GB, Labrie F, Giguère V. 1999. Ligand-independent recruitment of SRC-1 to estrogen receptor β through phosphorylation of activation function AF-1. Mol Cell 3:513–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Picard N, Charbonneau C, Sanchez M, Licznar A, Busson M, Lazennec G, Tremblay A. 2008. Phosphorylation of activation function-1 regulates proteasome-dependent nuclear mobility and E6-associated protein ubiquitin ligase recruitment to the estrogen receptor β. Mol Endocrinol 22:317–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Paruthiyil S, Cvoro A, Tagliaferri M, Cohen I, Shtivelman E, Leitman DC. 1 December 2010. Estrogen receptor β causes a G2 cell cycle arrest by inhibiting CDK1 activity through the regulation of cyclin B1, GADD45A, and BTG2. Breast Cancer Res Treat 10.1007/s10549-010-1273-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.