Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Burnout experienced by physicians is concerning because it may affect quality of care.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the frequency of burnout among physicians at an academic health science centre and to test the hypothesis that work hours are related to burnout.

METHODS:

All 300 staff physicians, contacted through their personal e-mail, were provided an encrypted link to an anonymous questionnaire. The primary outcome measure, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, has three subscales: personal, work related and patient related.

RESULTS:

The response rate for the questionnaire was 70%. Quantitative demands, insecurity at work and job satisfaction affected all three components of burnout. Of 210 staff physicians, 22% (n=46) had scores indicating personal burnout, 14% (n=30) had scores indicating work-related burnout and 8% (n=16) had scores indicating patient-related burnout. The correlation between total hours worked and total burnout was only 0.10 (P=0.14)

DISCUSSION:

Up to 22% of academic paediatric physicians had scores consistent with mild to severe burnout. A simple reduction in work hours is unlikely to be successful in reducing burnout and, therefore, quantitative demands, job satisfaction and work insecurity may require attention to address burnout among academic physicians.

Keywords: Evaluations, Job satisfaction, Work demands, Work hours

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

L’épuisement professionnel que vivent les médecins est préoccupant parce qu’il peut nuire à la qualité des soins.

OBJECTIF :

Déterminer la fréquence d’épuisement professionnel chez les médecins d’un centre de santé universitaire et vérifier l’hypothèse selon laquelle les heures de travail y sont liées.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les 300 médecins membres du personnel, avec qui les chercheurs ont communiqué par leur adresse de courriel personnelle, ont reçu un hyperlien crypté vers un questionnaire anonyme. La principale mesure d’issue, l’inventaire d’épuisement professionnel de Copenhague, comporte trois sous-échelles : personnelle, liée au travail et liée au patient.

RÉSULTATS :

Le taux de réponses au questionnaire s’élevait à 70 %. Les exigences quantitatives, l’insécurité au travail et la satisfaction au travail influaient sur les trois éléments de l’épuisement professionnel. Sur les 210 médecins membres du personnel, 22 % (n=46) avaient des indices laissant supposer un épuisement professionnel personnel, 14 % (n=30), des indices indicateurs d’un épuisement lié au travail, et 8 % (n=16), des indices indicateurs d’épuisement lié aux patients. La corrélation entre le nombre total d’heures travaillées et l’épuisement total s’élevait à seulement 0,10 (P=0,14).

EXPOSÉ :

Jusqu’à 22 % des médecins universitaires en pédiatrie obtenaient des indices évocateurs d’un épuisement professionnel léger à grave. Une simple réduction du nombre d’heures travaillées est peu susceptible de réussir à réduire l’épuisement professionnel. Par conséquent, il peut être justifié de se pencher sur les exigences quantitatives, la satisfaction au travail et l’insécurité au travail afin de régler la question de l’épuisement professionnel chez les médecins universitaires.

Physician wellness has been identified as a key quality indicator linked with an effective and safe hospital (1). Interaction between physicians and patients involves interpersonal or emotional demands with potential for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and, ultimately, burnout (2,3). The concept of burnout first emerged in the mid 1970s when two researchers, Christina Maslach (4) and Herbert Freudenberger (5), independently described burnout as a “negative consequence of human service work, characterized by emotional exhaustion, loss of energy, and withdrawal from work”. Burnout experienced by physicians is of particular concern because it may decrease the quality of patient care (1).

The modern medical workplace is complex, physicians’ responses vary greatly and several factors have been linked to physician burnout. Some physicians find the medical workplace stimulating, whereas others become stressed from working with too many patients, from the administrative requirements of medical practice (2) and from the responsibility for critical decisions with possible serious consequences for patients (6). Physicians may also work long hours due to on-call demands and increasing expectations from patients and families. For academic physicians, there are additional expectations for teaching and research. Although significant attention has been directed toward resident and house staff working hours (3,7), less attention has been directed toward the relationship between faculty burnout and working hours. The aim of the present study was to determine the frequency of burnout among physicians at a paediatric academic health science centre and to determine the relationship with hours worked.

METHODS

Study design

The Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, Ontario) has 330 inpatient beds, approximately 14,000 inpatient admissions, performs 11,000 surgical procedures, and attends to 50,000 emergency visits and 300,000 outpatient visits annually.

All full-time staff physicians, contacted through their personal e-mail, were provided an encrypted link to a questionnaire for a one-month period. Surveys were completed anonymously, and took 5 min to 10 min to fill out. The Hospital for Sick Children’s Research Ethics Board approved the study.

Burnout

The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI), a reliable and valid 19-item questionnaire (8), encompasses three different types of physical and psychological exhaustion: personal (six items), work related (seven items) and client related (six items). The six personal-burnout questions relate to physical and emotional fatigue. The seven work-related questions address the frustration and exhaustion associated with work. The client-related exhaustion questions were developed to address symptoms of frustration and emotional exhaustion associated with the person’s work involving patients, elderly citizens, pupils and/or inmates. In the present study, the questions were directed toward dealing with patients and the present study refers to this subscale as ‘patient-related burnout’. All questionnaire items have five response categories: always or to a very high degree; often or to a high degree; sometimes or somewhat; seldom or to a low degree; and never/almost never or to a very low degree. Responses in the present study were scaled from 0 to 100 for individual subscores as well as a total score – lower scores indicated less burnout and higher scores indicated more burnout. All scales were modified to be read the same way. For example, if the score was high, it would indicate more of that particular category (eg, for ‘job satisfaction’, the higher the number the more satisfied physicians are with their jobs; likewise, for ‘quantitative demands’, the higher the number the more demands physicians have). Because previous research has shown relatively high subscale correlation (8), for simplicity of analyses between work hours and burnout, all analyses were summed as total burnout.

Non-client-related psychosocial work environment factors

In addition to the CBI, the short version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionniare (CPQ) was used. The CPQ is a valid and reliable 44-item questionnaire, focusing on psychosocial working conditions, health and well-being (9): three items for quantitative work demands, two for emotional demands, one for sensorial demand, three for influence at work, two for possibilities for development, one for degree of freedom at work, two for meaning of work, two for commitment to the workplace, two for the amount of predictability involved with their jobs, two for quality of leadership, two for social support, two for feedback at work, two for sense of community, four for insecurity at work, four for job satisfaction, one for general health, five for mental health and four for vitality. All 44 items have five response categories: always or to a very high degree; often or to a high degree; sometimes or somewhat; seldom or to a low degree; and never/almost never or to a very low degree.

In addition, three questions were used in the present study: How often do you find the lack of resources to do the right thing for patients and families frustrating? Do you have sufficient time for family/friends? Rate this statement: “my relationship with partner/spouse is strong”. For the first and second questions, the response categories were ‘always’, ‘often’, ‘sometimes’, ‘seldom’ and ‘never/hardly ever’; higher scores indicated greater frequency. For the third question, the response categories were ‘definitely true’, ‘often true’, ‘sometimes true’, ‘often false’ and ‘definitely false’; higher scores indicated greater spousal support.

Sociodemographic factors

The sociodemographic characteristics assessed included age, sex, marital status, spouse’s occupation, number of children, full-time/part-time appointment, department, smoking, exercise, alcohol use, number of hours worked per week at work, number of hours worked per week at home and number of hours worked on average per week on-call.

Data analysis

Means for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables were provided. Analyses were performed using multiple regression for the three independent variables: personal burnout, work-related burnout and patient-related burnout. A sample size of 201 achieved 90% power to detect an R2 of 0.1000 attributed to 15 variables using an F-test with a significance level (alpha) of 0.05. Variables were grouped into six clusters of homogeneous variables. From each of the six clusters, a single variable (with highest intra- and lowest intercluster correlation) was chosen. In addition to these six variables, the following variables were added to the regressions: age, sex, marital status, department and hours worked. The percentage of physician burnout was calculated based on the average score for all of the questions in each component of the burnout questionnaires – individuals with an average score of greater than 3 (at least ‘sometimes or somewhat’) for all questions were considered to be ‘burnt out’ (8).

RESULTS

The response rate of the study was 70.1% (212 of 300). Of the 212 physicians who responded, 201 were used in the final regression analyses. The other 11 surveys were partially incomplete. The responses to the demographic questions are provided in Table 1. The average responses to the CPQ are provided in Table 2. The mean (± SD) score for personal burnout was 39±17%; 22% (46 of 210) of staff physicians’ scores indicated personal burnout. The mean score for work-related burnout was 34±16%; 14.3% (30 of 210) of staff physicians’ scores indicated work-related burnout. The mean score for patient-related burnout was 25±17%; 7.6% (16 of 210) of staff physicians reported patient-related burnout.

TABLE 1.

Demographics: Items and responses

| Question | Response, % |

|---|---|

| How old are you? Age, years, mean ± SD | 46.73±9.05 |

| What is your sex? | |

| Male | 59.4 |

| Female | 40.6 |

| What is your marital status? | |

| Common law | 7.5 |

| Divorced | 6.6 |

| Married | 73.6 |

| Single | 10.8 |

| Widow(er) | 1.4 |

| What is your spouse’s occupation? | |

| Attending school | 1.9 |

| Employed | 59.4 |

| Unemployed | 1.4 |

| Homemaker | 17.9 |

| Retired | 2.4 |

| No spouse | 17 |

| How many children do you have? | |

| 0 | 18.9 |

| 1 | 6.1 |

| 2 | 39.2 |

| 3 | 20.3 |

| 4 | 10.4 |

| 5 | 2.8 |

| 6 | 1.4 |

| 7 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 |

| 9 | 0.9 |

| 10 | 0 |

| Are you a full time (>0.75 FTE) SickKids physician? | |

| Yes | 89.2 |

| No | 10.8 |

| How many hours do you work per week at work? | |

| <10 | 0 |

| 10–20 | 1.4 |

| 21–30 | 2.4 |

| 31–40 | 7.1 |

| 41–50 | 22.2 |

| 51–60 | 39.2 |

| 61–70 | 19.8 |

| 71–80 | 6.6 |

| 81–90 | 1.4 |

| >90 | 0 |

| How many hours do you work per week at home? | |

| <10 | 1.4 |

| 10–20 | 42.5 |

| 21–30 | 42.5 |

| 31–40 | 12.3 |

| 41–50 | 0.9 |

| 51–60 | 0 |

| 61–70 | 0 |

| 71–80 | 0 |

| 81–90 | 0 |

| >90 | 0.5 |

| How many hours on average do you work per week on-call? | |

| <10 | 29.7 |

| 10–20 | 26.9 |

| 21–30 | 12.7 |

| 31–40 | 9 |

| 41–50 | 5.2 |

| 51–60 | 2.8 |

| 61–70 | 3.3 |

| 71–80 | 1.9 |

| 81–90 | 0.9 |

| >90 | 0.9 |

| N/A | 6.6 |

| What is your research institute designation? | |

| (Sr) Scientist | 15.6 |

| (Sr) Associate Scientist | 16 |

| Project Director | 39.6 |

| None | 28.8 |

| What is your department? | |

| Anesthesia | 7.5 |

| Critical Care | 2.4 |

| Dentistry | 1.4 |

| Pathology and Laboratory Medicine | 0.9 |

| Diagnostic Imaging | 2.8 |

| Ophthalmology | 4.2 |

| Otolaryngology | 1.4 |

| Paediatrics | 58.5 |

| Psychiatry | 7.5 |

| Surgery | 13.2 |

| Do you smoke? | |

| Never smoked | 86.3 |

| Former smoker | 12.3 |

| Current smoker | 1.4 |

| How many cigarettes do (did) you smoke per day? | |

| 0 | 87.7 |

| 1 | 0.9 |

| 2 | 0.9 |

| 3 | 0.5 |

| 4 | 0.5 |

| 5 | 0.5 |

| 6 | 0.9 |

| ≥7 | 8 |

| How many times per week do you exercise for more than 30 minutes? | |

| 0 | 19.8 |

| 1 | 15.6 |

| 2 | 17 |

| 3 | 21.7 |

| 4 | 9.9 |

| ≥5 | 16 |

| How many alcoholic drinks do you have per week? | |

| 0 | 20.3 |

| 1 | 21.2 |

| 2 | 13.2 |

| 3 | 10.4 |

| 4 | 14.2 |

| ≥5 | 20.8 |

FTE Full-time employment; N/A Not answered; SickKids The Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, Ontario)

TABLE 2.

Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire: Summary scores

| Score, mean ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Quantitative demands | 60.0±16.00 |

| Emotional demands | 52.5±18.25 |

| Sensorial demands | 50.0±27.50 |

| Influence at work | 55.0±20.00 |

| Possibilities for development | 82.5±14.00 |

| Degree of freedom at work | 60.0±26.00 |

| Meaning of work | 90.0±12.75 |

| Commitment to the workplace | 72.5±19.00 |

| Amount of predictability involved with the job | 57.5±18.00 |

| Quality of leadership | 57.5±26.00 |

| Social support | 47.5±21.00 |

| Feedback at work | 62.5±20.00 |

| Sense of community | 67.5±19.25 |

| Insecurity at work | 5.4±1.13 |

| Job satisfaction | 77.5±14.5 |

| General health | 75.0±23.25 |

| Mental health | 65.0±8.00 |

| Vitality | 47.5±9.50 |

| Role clarity | 70.0±16.25 |

| Role conflicts | 57.5±18.50 |

| Behavioural stress | 77.5±20.50 |

| How often do you find the lack of resources to do the right thing for patients and families frustrating? | 40.0±26.75 |

| Do you have sufficient time for family/friends? | 27.5±42.00 |

| Rate this statement: “my relationship with partner/spouse is strong” | 45.0±20.25 |

Insecurity at work, quantitative demands and job satisfaction were significantly related to all three components of burnout as well as total burnout (Table 3). Although insecurity at work overall was infrequent (resulting in a low overall mean), those who reported insecurity also reported high levels of burnout. Work-related burn-out was also significantly related to sex, possibilities for development and a sense of community along with the other three factors mentioned above. Women were significantly more likely to experience work-related burnout. An increase in possibilities for development and an increase in sense of community significantly decreased the likelihood of work-related burnout. Patient-related burnout was negatively correlated to being single; that is, single physicians were significantly less likely to report patient-related burnout, along with the other three factors mentioned above (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics significantly correlated with Copenhagen Burnout Inventory subscale scores

| Characteristics |

Parameter estimate (SE) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal burnout | Work-related burnout | Patient-related burnout | Total burnout | |

| Female sex | – | 3.8 (1.8); P=0.0374 | – | – |

| Single (marital status) | – | – | −6.9 (2.6); P=0.008 | −4.7 (2.2); P=0.03 |

| Quantitative demands | 5.5 (1.6); P=0.0007 | 6.7 (1.4); P<0.0001 | 3.0 (1.7); P=0.02 | 5.5 (1.3); P=0.0001 |

| Possibilities for development | – | −3.6 (1.8); P=0.04 | – | – |

| Sense of community | – | −4.1 (1.4); P=0.0036 | – | – |

| Insecurity at work | 13.5 (6.1); P=0.0290 | 11.5 (5.7); P=0.04 | 25 (6.3); P=0.0001 | 17.0 (5.1); P=0.001 |

| Job satisfaction | −14.5 (1.8); P<0.0001 | −12 (1.9); P<0.0001 | −10.0 (1.9); P<0.0001 | −12.4 (1.5); P=0.0001 |

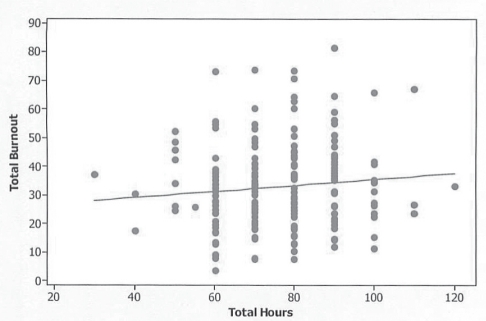

As indicated in Table 1, the hours worked per week ranged widely. However, hours worked at home, hours worked at work, hours worked on-call or total hours (combination of hours worked at work, hours worked at home and hours worked on-call per week) were not related (r=0.02 [P=0.77], r=0.08 [P=0.25], r=0.04 [P=0.52], r=0.09 [P=0.2], respectively) to total burnout (combination of patient-related burnout, work-related burnout and personal burnout) (Figure 1). The correlation between quantitative work demands and total burnout with hours of work was 0.28 (P=0.001) and 0.1 (P=0.14), respectively.

Figure 1).

Combination of patient-related burnout, work-related burn-out and personal burnout

DISCUSSION

The present study found that 22% of academic paediatric physicians had scores consistent with mild to severe burnout. While work hours were not related, quantitative demands, job satisfaction and work insecurity were all related to burnout. While comparisons among studies are complicated by different scales and different thresholds, the levels of burnout in our study are comparable with or higher than levels reported in other studies (10).

Burnout may have significant and detrimental effects on individuals including absenteeism, poor health, physical exhaustion, increased use of drugs and alcohol, depressive disorders, marital and family problems, increased job turnover, poor health, early retirement and even morbidity (1). Negative outcomes include a decrease in job satisfaction and self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression (11). Campbell et al (12) reported that surgeons who experienced burnout were less likely to develop friendships outside of medicine, and were interested in retraining in nonsurgical areas or even leaving medicine entirely. Depersonalization can also be harmful to relationships with colleagues and patients (2). Finally, and perhaps most important, burnout can cause medical errors with a reduction in patient satisfaction (8).

Burnout is multifactorial and appears to be specific to particular domains. The CBI provides three independent subscales – work-related, personal and patient-related – reflecting the different aspects of physicians’ activities. While burnout may occur in all spheres, consistent with the findings of Borritz et al (8) for hospital physicians, the physicians in our study more often reported work-related and personal as opposed to patient-related burnout. Sargent et al (3) reported that for orthopedic residents and faculty, work overload, insufficient rewards, lack of fairness, lack of control, lack of community and conflicting values were all related to burnout. Our study found that three factors were consistently related to all aspects of burnout: job satisfaction, work insecurity and quantitative demands. The results of the present study confirm that institutions should be directly evaluating and developing strategies to improve physician wellness (1).

Although in some occupations, the number of hours worked per week is related to burnout (11), a previous study (2) found that working conditions for internists were more important in explaining the variance in burnout than the number of hours worked per week. Our study, which focused on academic paediatric physicians, also found that the number of hours worked per week was not related to burnout. Hours worked was also weakly correlated with quantitative work demands. This finding is consistent with those of Keeton et al (13), who found that having control over the hours worked was the key determinant of burnout. While many strategies may be used to improve physician wellness, work hours provide one of the simplest and most objective parameters to measure. However, the findings suggest that simply monitoring or regulating work hours for academic physicians will not reduce burnout. The critical issue for academic physicians will be determining whether the workload matches the available hours and the perceived quantitative workload.

Other studies have found strong inter-relationships among low levels of job satisfaction, burnout and organization factors (14–17). Although increased job satisfaction may decrease the risk of burn-out, the reverse is also probably true, whereby burnt out physicians are less likely to be satisfied with their job. Kushnir and Cohen (18) reported that the least satisfying, and thus a potential cause of burnout, was administrative work and paperwork. In a study conducted by Van Ham et al (17), one of the factors that influenced burnout was physician job satisfaction and factors that increased job satisfaction were diversity of work, relationships and contact with colleagues, and being involved in teaching medical students. Factors that decreased job satisfaction were low income, too many working hours, administrative burdens, heavy workload, lack of time and lack of recognition.

A factor associated with work-related burnout in our study was work insecurity. A previous study (19) reported that work insecurity was also associated with absence due to sickness and an increased risk of depression. The Hospital for Sick Children has an alternative funding plan whereby the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care provides block funding. Although this will help remove the stress and work demands associated with the fee-for-service method, job security may be influenced by the potentially more subjective and unlimited demands of academic performance. This finding suggests the need for ongoing discussions about expectations with academic physicians. Our study also found a relationship between sex and work-related burnout. Being single decreased the likelihood of developing patient-related burnout. Contrary to other articles that conclude spouses to be a good resource for support (20), our data suggest that having a partner increases the possibility of developing burnout. McMurray et al (21) concluded that lack of workplace control predicted burnout in women but not in men. Thus, sex and marital status are issues that need to be considered when analyzing risk of work-related burnout for academic physicians.

Increasing physicians’ sense of community and/or increasing their possibilities for development are other strategies that could be beneficial in reducing the risk of burnout. Although not addressed in our study, mentoring and peer support may be useful in increasing a sense of community. Kushnir and Cohen (18) suggested that burn-out might be reduced by modifying work structure by including more varied and challenging activities such as participating in research and community health promotion, and by being more involved in professional interactions with other professionals. They also suggested that administrative tasks be reduced to a minimum level to prevent stress and burnout, possibly by delegating tasks to other personnel to allow physicians to engage in other activities such as more teaching and supervising of medical students, and participating in continuing medical education and their own medical research. Finally, relatively short one-day individual counselling was shown in one previous study (22) to have the potential to reduce emotional exhaustion and the length of sick leave for physicians.

The present study has several potential limitations. First, the questionnaire was administered in a single rather than multiple hospitals. However, we have no reason to believe that the results would not be typical of other academic hospitals. A second potential limitation was desirability bias. However, to minimize this limitation, questionnaires were completed anonymously and the term ‘burnout’ was not used in the study. Third, the percentage of physicians deemed to be burnt out was questionnaire specific. Although alternative questionnaires may establish different absolute percentages for burnout, burnout is clearly an issue for some academic physicians. Fourth, for some physicians burnout may be a reflection of depression, which may require individual, in addition to institution-wide, initiatives. However, burnout may precipitate or aggravate depression. Furthermore, specific attention to physician wellness at an institutional level may identify depressed physicians. Finally, hours worked was based on self-report. Future research will need to directly address the validity of self-report.

CONCLUSION

Up to 21% of academic physicians reported mild to severe burnout. Overall, burnout was not related to hours worked, but was related to decreased job satisfaction, increased work insecurities and increased quantitative demands. Physicians are more likely to burn out from work-related and personal as opposed to patient-related problems. A simple reduction in work hours is unlikely to be successful and more attention needs to be directed toward addressing quantitative work demands to reduce burnout experienced by academic physicians.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT AND DISCLAIMERS:

This article was supported by the Robert B Salter Chair in Pediatric Research at The Hospital for Sick Children.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: A missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374:1714–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A, Benos A. Burnout in internal medicine physicians: Differences between residents and specialitsts. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sargent MC, Sotile W, Sotile MO, Rubash H, Barrack RL. Stress and coping among orthopaedic surgery residents and faculty. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86:1579–86. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maslach C. Burned-out. Hum Behav. 1976;5:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freudenberger HJ. Staff burn-out. J Social Issues. 1974;30:159–207. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozyurt A, Hayran O, Sur H. Predictors of burnout and job satisfaction among Turkish physicians. J Assoc Physicians. 2006;99:161–9. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinbrook R. The debate over residents’ work hours. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1296–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr022383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borritz M, Rugulies R, Bjorner JB, Villadsen E, Mikkelsen OA, Kristensen TS. Burnout among employees in human service work: Design and baseline findings of the PUMA study. Scand J Public Health. 2006;34:49–58. doi: 10.1080/14034940510032275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristensen TS, Hannerz H, Høgh A, Borg V. The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire – a tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2005;31:438–49. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruce SM, Conaglen HM, Conaglen JV. Burnout in physicians: A case for peer-support. Intern Med J. 2005;35:272–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2005.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnett RC, Gareis KC, Brennan RT. Fit as mediator of the relationship between work hours and burnout. J Occup Health Pscyhol. 1999;4:307–17. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.4.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell DA, Jr, Sonnad SS, Eckhauser FE, Campbell KK, Greenfield LJ. Burnout among American surgeons. Surgery. 2001;130:696–705. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keeton K, Fenner DE, Johnson TR, Hayward RA. Predictors of physician career satisfaction, work-life balance, and burnout. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:949–55. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000258299.45979.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burisch M. A longitudinal study of burnout: The relative importance of dispositions and experiences. Work Stress. 2002;16:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, Cull A, Gregory WM. Mental health of hospital consultants: The effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet. 1996;347:724–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renzi C, Tabolli S, Ianni A, Di Pietro C, Puddu P. Burnout and job satisfaction comparing healthcare staff of a dermatological hospital and a general hospital. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:153–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Ham I, Verhoeven AA, Groenier KH, Groothoff JW, De Haan J. Job satisfaction among general practitioners: A systematic literature review. Eur J Gen Practice. 2006;12:174–80. doi: 10.1080/13814780600994376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kushnir T, Cohen AH. Job structure and burnout among primary care pediatricians. Work (Reading, Mass) 2006;27:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Souza RM, Strazdins L, Lim LL, Broom DH, Rodgers B. Work and health in a contemporary society: Demands, control, and insecurity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;243:849–54. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.11.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saleh KJ, Quick JC, Conaway M, et al. The prevalence and severity of burnout among academic orthopaedic departmental leaders. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89:896–903. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMurray JE, Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, Shugerman R, Nelson K. The work lives of women physicians results from the physician work life study. The SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:372–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2000.im9908009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rø KE, Gude T, Tyssen R, Aasland OG. Counselling for burnout in Norwegian doctors: One year cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2004. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]