Abstract

Background

Adaptive properties of the bone-PDL-tooth complex have been identified by changing the magnitude of functional loads using small-scale animal models such as rodents. Reported adaptive responses as a result of lower loads due to softer diet include decreased muscle development, change in structure-function relationship of the cranium, narrowed PDL-space, changes in mineral level of the cortical bone and alveolar jaw bone, and glycosaminoglycans of the alveolar bone. However, the adaptive role of the dynamic bone-PDL-cementum complex due to prolonged reduced loads has not been fully explained to date, especially with regards to concurrent adaptations of bone, PDL and cementum. Hence, the temporal effect of reduced functional loads on physical characteristics such as morphology and mechanical properties, and mineral profiles of the bone-periodontal ligament (PDL)-cementum complex using a rat model was investigated.

Materials and Methods

Two groups of six-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats were fed nutritionally identical food with a stiffness range of 127–158N/mm for hard pellet or 0.32–0.47N/mm for soft powder forms. Spatio-temporal adaptation of the bone-PDL-cementum complex was identified by mapping changes in: 1) PDL-collagen orientation and birefringence using polarized light microscopy, bone and cementum adaptation using histochemistry, and bone and cementum morphology using micro X-ray computed tomography, 2) mineral profiles of the PDL-cementum and PDL-bone interfaces by X-ray attenuation, and 3) microhardness of bone and cementum by microindentation of specimens at ages six, eight, twelve, and fifteen weeks.

Results

Reduced functional loads over prolonged time resulted in 1) altered PDL orientation and decreased PDL collagen birefringence indicating decreased PDL turnover rate and decreased apical cementum resorption; 2) a gradual increase in X-ray attenuation, owing to mineral differences, at the PDL-bone and PDL-cementum interfaces without significant differences in the gradients for either group; 3) significantly (p<0.05) lower microhardness of alveolar bone (0.93±0.16 GPa) and secondary cementum (0.803±0.13 GPa) compared to the higher load group (1.10±0.17 GPa and 0.940±0.15 GPa respectively) at fifteen weeks indicating a temporal effect of loads on local mineralization of bone and cementum.

Conclusions

Based on the results from this study, the effect of reduced functional loads for a prolonged time could differentially affect morphology and mechanical properties, and mineral variations and of the local load-bearing sites in a bone-PDL-cementum complex. These observed local changes in turn could help explain the overall biomechanical function and adaptations of the tooth-bone joint. From a clinical translation perspective, our study provides an insight into modulation of load on the complex for improved tooth function during periodontal disease, and/or orthodontic and prosthodontic treatments.

Keywords: functional loads, tissue interfaces, cementum, bone-tooth biomechanics, alveolar bone, periodontal ligament

1. INTRODUCTION

Mechanical loads are important in maintaining joint function (1). In the masticatory system, functional loads on a bone-tooth fibrous joint (2) are enabled by the muscles of mastication including the masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid, and the upper/lower lateral pterygoid (3). Magnitudes and frequencies of functional loads are dependent on many intrinsic and extrinsic factors (4) including muscle efficiency (e.g. higher in men than in women, higher in younger than in older (5–7)), hardness of diet (e.g. softer foods and/or liquid diet. vs. harder foods (8–10)), and other forms of habitual loads (e.g. nail biting, tongue trusting, jaw clenching, bruxism (11–13)). As a result, functional loads cause a combination of axial and horizontal loads, resulting in tooth movement in all directions relative to the alveolar bone (5, 14). Hence it is conceivable that a change in magnitude of functional loads due to any or a combination of the aforementioned factors can change the axial and lateral loads on a tooth and its relative position within the alveolar socket.

The unique anatomy of the bone-tooth joint features two different hard tissues, cementum and alveolar bone, attached by the fibrous periodontal ligament (PDL) (2). Cementum is a mineralized composite of fibrillar and nonfibrillar proteins (organic range of 45–60%), and inorganic apatite (inorganic range of 40–55%) with a lamellar-like structure (15). Alveolar bone has similar ranges of organic and inorganic contents, but the structure of the extracellular matrix is different from cementum. Alveolar bone is vascularized, and goes through physiological remodeling and significant response to mechanical loads identified as modeling of bone (16, 17). Attached to cementum and bone is the vascularized and innervated PDL, which is critically important in adaptive responses and is responsible for tooth movement relative to the alveolar socket and resulting strain fields within the bone-PDL-cementum complex. Unlike diarthroidal joints of the musculoskeletal system (18), the bone-tooth fibrous joint has a limited range of motion (19) during function. Within the bone-PDL-cementum complex, bone, cementum, PDL, PDL-bone and PDL-cementum attachment sites, and the interfaces between soft (PDL) and hard tissues (bone and cementum i.e. both primary (PC) and secondary cementum (SC)) jointly serve the common function of mechanical stress dissipation (20) caused by dynamic loads. Over time, tissues, soft-hard tissue attachment sites, and interfaces adapt to loads in ways identifiable by changes in physical and chemical properties resulting in morphologically unique dental organs (16, 17). Following development, functional loads on the bone-tooth complex cause predominant strain fields in the PDL and stress fields that are more pronounced in bone and cementum (21). Strains within the PDL and at the PDL-bone and PDL-cementum attachment sites (entheses) initiate many of the local adaptive responses of the complex. Hierarchical mapping of load-mediated stimuli to cells to tissue manifesting into organ function will provide an improved basis for understanding and explaining many of the controversies in clinical dentistry.

Functional (overload, disuse and directional loads) adaptations in bone, cementum and the PDL are often evaluated with systematic studies using small-scale animal models such as rodents (22). For over thirty years (22–24) tissues of the rat bone-PDL-cementum complex have been used to investigate load-mediated adaptation. Adaptive properties of the bone-PDL-tooth complex have been identified by changing the magnitude of functional loads using various models: hypo- and hyper-occlusion (25, 26), unopposed teeth (27), orthodontic forces (28), and soft and hard diets (22). Reported adaptive responses as a result of lower loads due to softer diet include decreased muscle development (29, 30), change in structure-function relationship of the cranium, narrowed PDL-space (31), changes in mineral level of the cortical bone and alveolar jaw bone (32, 33), and glycosaminoglycan (32) content of alveolar bone. However, the adaptive role of the dynamic bone-PDL-cementum complex due to prolonged reduced loads has not been fully explained to date, especially with regards to concurrent adaptations of bone, PDL and cementum. In this study it is hypothesized that prolonged functional loads will change the local physical characteristics of the bone-tooth complex. Hence our objectives were to identify changes in 1) PDL birefringence and orientation using polarized light microscopy coupled with picrosirius red staining, 2) adaptive responses by mapping resorptive patterns of cementum and reversal lines in alveolar bone, and 3) mineral gradients at the bone-PDL and cementum-PDL attachment sites using Micro X-ray computed tomography (Micro XCT), 4) changes in mechanical hardness of cementum and bone using microindentation in specimens harvested from rats subjected to soft and hard diets for prolonged time.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals and Experimental Diet

Fifty-six 6-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and housed at UCSF Animal Facilities. Animal housing, care, and euthanasia protocol complied with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of UCSF and the National Institutes of Health. Rats were randomly allocated to higher (N=32) or lower (N=24) functional load groups by feeding them nutritionally identical food (PicoLab 5058, LabDiet, PMI), in either hard pellet or soft powder form. The rats were allowed food and water ad libitum. At the zero time point (age 6 weeks) considered as baseline, eight rats (N=8) were sacrificed as controls, and by default belonged to the higher functional load group as they are normally fed hard pellets after being weaned. At the subsequent time points: 8, 12, and 15 weeks, eight rats (N=8) from each group were sacrificed, and their mandibles immediately harvested for specimen preparation.

2.2. Food Stiffness

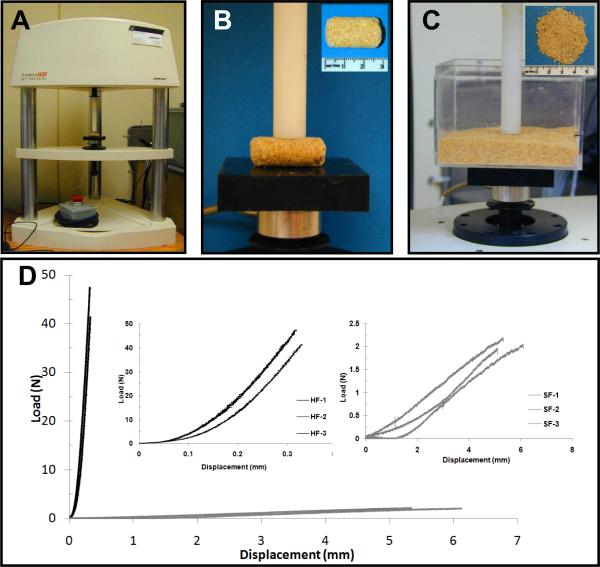

Compression tests were conducted using a mechanical testing device (Fig.1A, EnduraTec, Bose Electrofoce 3200 system, Minnetonka, MN), and by individually loading hard pellets (Fig.1B) and bulk soft powder (Fig.1C). Soft food was loaded at a rate of 0.1 mm/s to an average maximum displacement of 5.52 mm. Soft food was loaded at a faster rate to prevent discrepancies due to particle disbursement within the container. The Student's t-test with 95% confidence interval indicated significant differences in mean stiffness (P < 0.05) of hard food at 150±15 N/mm compared to soft food at 0.4±0.1 N/mm.

Figure 1.

A) Compression testing system. B) Individual unconfined hard pellets loaded in compression to determine stiffness of hard food. C) Powdered soft food confined within a hard plastic container and compressively loaded to determine stiffness of soft food. D) Stiffness of the hard food (HF 1–3) and soft food (SF 1–3) was determined by the slope of the linear portion of the load versus displacement curve. Mean stiffness of hard food: 150 ± 15 N/mm and soft food: 0.4 ± 0.1 N/mm.

2.3. Histology

Half of the left mandibles from each group at each time point (N=4) were fixed in formalin, demineralized in Immunocal (Decal Chemical Corporation, Tallman, NY), then embedded in paraffin, from which 5–6 μm thick sections were taken and mounted, deparaffinized with xylene, and stained with either hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Picrosirius Red. The stained tissues were characterized for structural orientation and integration of the PDL with bone and cementum, using a light microscope (BX 51, Olympus America Inc., San Diego, CA) and analyzed using Image Pro Plus v6.0 software (Media Cybernetics Inc., Silver Springs, MD).

2.4. Micro X-Ray Computed Tomography (Micro XCT)

The left mandibles (N=4) from each group at each time point were fixed and imaged in 70% ethanol. Each specimen was scanned (Micro XCT-200, Xradia Inc., Pleasanton, CA) with identical experimental parameters, 75 KVp, 6W at 4× magnification, then reconstructed in 3D (Fig.2A) and viewed with identical contrast and brightness settings. Virtual parallel slices (from reconstructed tomographies) were used to bisect the distal root of the second mandibular molar by indentifying the apical orifice as a landmark. Additionally, transverse sections of the distal root of the second molar (Fig.2D) for each specimen were analyzed using Image J™. X-ray attenuation of alveolar bone and cementum as a function of distance from the PDL-space after normalizing intensity values within each specimen was plotted using MATLAB® R2008a (MathWorks®, El Segundo, CA). Measurements were made using transverse sections (Fig. 2) to avoid cortical bone and endosteal and/or other vascular spaces and were limited to 80 μm in bone and cementum, respectively.

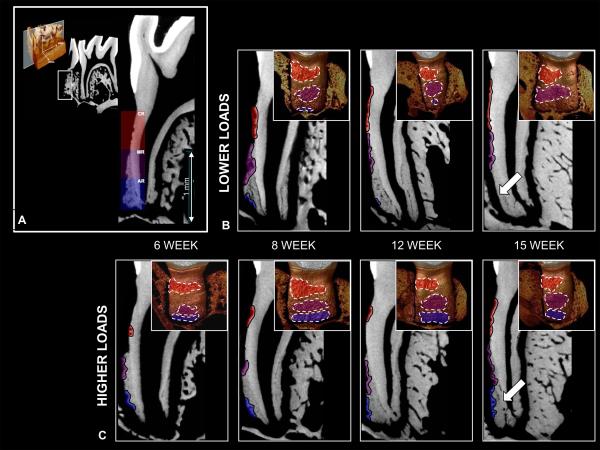

Figure 2.

A) 3D reconstruction of mandibular molar region. B–D) Reconstructed 2D slices representing coronal, middle and apical regions, buccal-lingual (B), mesial-distal (C), and occusal-apical (D) planes respectively. The coronal region (CR), all primary cementum, in red, the mid-root region (MR), spanning the interface of the primary and secondary cementum, in purple, and the apical region (AR), all secondary cementum, in blue are shown. Scale bar = 1mm

2.5. Ultrasectioning of specimens and microindentation

The bone-PDL-tooth complex of the distal root of the second molar was sectioned from the right mandibles from each group at each time point (N=4), and then glued to an AFM steel stub (Ted Pella, Inc., CA) using epoxy. A diamond knife (MicroStar Technologies, Huntsville, TX) was used to perform final sectioning by removing 300nm thin sections (34). The sectioned surface of the remaining block was characterized for PC, SC and alveolar bone using a light microscope.

Microhardness values of bone and cementum were evaluated to distinguish significant influences of loading over time. Microindentation on mineralized tissues using ultrasectioned blocks (N=4) was performed under dry conditions with the use of a microindenter (Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL) and a Knoop diamond indenter (Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL). Each specimen was indented in cementum and bone and the distance between any two indents was chosen per ASTM standard (35). Statistically significant differences between groups were determined using Student's t-test with a 95% confidence interval.

3. RESULTS

3.1. PDL-collagen fiber organization

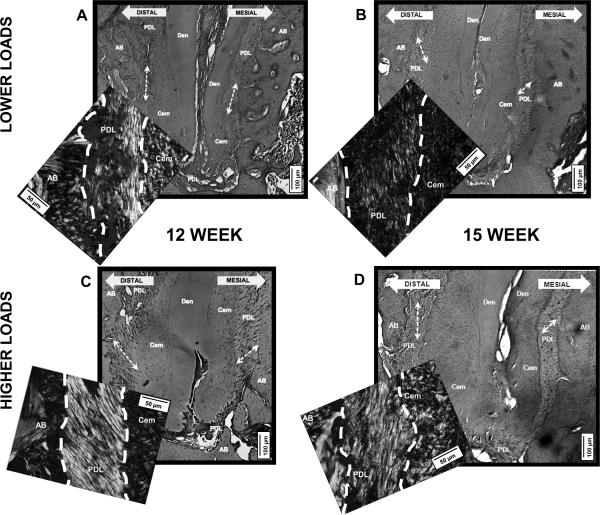

Polarized light microscopy of picrosirius red stained sections of M2-distal root (M2/D, see supplementary material) revealed distinct differences between PDL-collagen fibers with lower loads compared to higher loads (Fig.3). PDL-collagen fibers subjected to lower loads were birefringent (Figs.3A, 3B), but were disorganized, with lower intensity, and patchy appearance. PDL-collagen fibers subjected to higher loads demonstrated a strong birefringence (Figs.3C, 3D), and were well oriented and organized.

Figure 3.

Light microscope images of distal root of molar 2 (M2/D) stained with H&E at 10× to illustrate the variations in PDL-orientation. Representative insets of polarized light micrographs of picrosirius red stained bone-PDL-cementum attachment sites of M2/D at 40×. A, B) M2/D subjected to lower loads illustrates less organized PDL-collagen fibrils, patchy and dim PDL-birefringence. C, D) M2/D subjected to higher loads illustrates organized PDL-collagen fibrils, distinct and bright appearance of the PDL. AB = alveolar bone, Cem = cementum, Den = dentin, PDL = periodontal ligament. Scale bars = 100 μm, inset scale bars = 50 μm

3.2. Regional cementum resorption patterns and bone modeling activity

3D reconstructions of the M2/D region subjected to lower and higher loads demonstrated regional pitting on the distal root surface, a characteristic of resorption activity at the PDL-cementum attachment site. A representative 2D slice of M2/D shown in Fig.4A illustrates the affected regions: the coronal region (CR) in primary cementum (PC), the mid-root region (MR) spanning the transition between PC and secondary cementum (SC), and the apical region (AR) with only SC. Extensive resorption was observed in the CR and MR regions (Fig.4B) at all time points in rats subjected to lower loads. Apposition of SC is seen with age as expected in both groups, but cementum resorption in the AR region decreased over time in rats subjected to lower loads.

Figure 4.

A) Representative resorption sites on mesial-distal 2D slice of a mandibular second molar. Areas of resorption are colored in both mesial-distal 2D reconstructed slices and corresponding tomographs for all groups. Extensive resorption can be observed in the CR and MR regions for all groups. However, in the lower functional load groups (B) there is little or no resorption in the AR region compared to the higher functional load groups (C) (white arrows).

In rats subjected to higher loads (Fig.4C), the distribution of cementum resorption in the CR and MR regions is similar to those subjected to lower loads at all time points. Also, SC apposition occurred with age. However, with prolonged time a marked increase in areas of SC resorption in the AR region in teeth loaded with higher functional loads compared to teeth loaded with lower functional loads was observed (areas of SC resorption patterns highlighted in Figure 4).

Analysis of H&E stained light micrographs of M2/D illustrated a distribution of reversal lines (Fig.5) corresponding to regional patterns of cementum resorption identified in Fig.4. In rats subjected to lower loads (Fig.5B), reversal lines in bone increased with time, especially in the CR region opposing areas of PC resorption. In contrast, rats subjected to higher loads (Fig.5C) had reversal lines in bone increased with time, but predominantly in the AR region opposing areas of SC resorption.

Figure 5.

A) Representative tomograph and 2D sagittal section illustrating the examined regions of the bone-PDL-cementum complex subjected to lower (B) and higher (C) loads. B, C) Light micrographs of M2/D at 20× illustrating variations in reversal lines (black lines) in AB. B) Reversal lines increase with age in the CR region opposing areas of primary cementum resorption (white arrows). C) Reversal lines increase with age in the AR region opposing areas of secondary cementum resorption (white arrows). AB = alveolar bone, Cem = cementum, PDL = periodontal ligament. Scale bars = 100 μm

3.3. Mineral gradients at the PDL-bone and PDL-cementum interfaces

2D reconstructed slices of M2/D region revealed gradients in X-ray attenuation at the PDL-bone interface, and at the PDL-cementum interface with nearly constant values of attenuation in bone and cementum respectively for both lower and higher loads at all time points (Fig.6). The results in Fig.6 illustrate that the first 25 μm near the PDL-bone (Figs. 6B and 6E) and first 15 μm near the PDL-cementum (Figs. 6C and 6F) attachment sites are less mineralized than the respective bulk tissues. Although no significant differences were observed, X-ray attenuation was lower in bone and cementum subjected to lower loads (Figs. 6B and 6C) than in respective tissues subjected to higher loads (Figs. 6E and 6F; note the scale bars for respective plots; Figs. 6E and 6F share the same scale bar).

Figure 6.

A,D) Transverse sections illustrating trailing and leading envelopes of the tooth as darker and lighter attenuating regions (white arrows). A-represents bone-tooth complex subjected to lower loads and D-represents bone-tooth complex subjected to higher loads. X-ray intensity profiles illustrate gradients (normalized) due to mineral variation in alveolar bone near the PDL-bone interface, and PDL-cementum interface of secondary cementum for lower (B and C) and higher (E and F) functional loads at all time points in bone and secondary cementum. Note: The 6 week higher load group is also shown in the lower load for ease of comparison. For all time points and locations, the intensity gradually increases in the first 25μm (for bone) or 15 μm (for cementum) from the PDL-space into mineralized tissue with no significant differences between the higher and lower load groups. An apparent decrease in X-ray attenuation in bone and cementum subjected to lower loads (B and C) compared to higher (E and F) loads was observed. M2=molar 2, PDL-Min. Tissue Enth. = Enthesis of PDL-respective mineralized tissue

3.4. Mechanical properties of bulk SC and bone

Knoop hardness of cementum increased from 0.51±0.11 GPa at 6 weeks (baseline) to 0.94±0.15 GPa at 15 weeks, while in the lower load group hardness increased to 0.80±0.13 GPa at 15 weeks (Fig.7A). Additionally, cementum subjected to higher loads was significantly harder (P<0.05) at 12-week (0.90±0.15 GPa) and 15-week (0.94±0.15 GPa) compared to those at lower loads (0.78±0.15 GPa and 0.80±0.13 GPa) respectively (Fig 7A).

Figure 7.

A) Mean hardness values of alveolar bone for higher and lower load groups at each time point. B) Mean hardness values of secondary cementum determined by microindentation for higher and lower load groups at each time point. Range of hardness values are represented by gray lines above (maximum) and below (minimum). At all experimental time points (8, 12, and 15 weeks) respective bone and cementum hardness values in the higher load group was greater than in the lower load group. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (p<0.05) between groups at the 12 and 15 week time points. C) Light microscope images illustrate microindents in alveolar bone (AB) and secondary cementum (CEM). PDL = Periodontal Ligament, DEN = Dentin. Scale bar = 100μm

Knoop hardness of bone increased from 0.64±0.14 GPa at 6 weeks (baseline) to 1.1±0.17 GPa at 15 weeks, while in lower load group hardness increased to 0.93±0.16 GPa at 15 weeks (Fig.7). Bone subjected to higher loads was significantly harder (P<0.05) at the 12-week (1.0±0.19 GPa) and 15-week (1.1±0.17 GPa) time points than when subjected to lower loads (0.89±0.18 GPa and 0.93±0.16 GPa) respectively (Fig. 7B).

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, functional loads were modulated by changing the hardness of the food (8, 29, 30), a hard pellet diet with a higher compressive strength, compared to a soft powder diet with negligible compressive strength (Fig.1). Consequently, rats on a hard pellet diet experienced higher functional loads, while those fed soft, powdered diet experienced lower functional loads (Fig.1) (22, 36). Subsequently, adaptation to higher and lower loads was investigated by spatial (CR, MR, AR) (Fig.2) and temporal mapping (6, 8, 12 and 15 weeks) of changes in physical and chemical properties. The chain of events leading to observed adaptation in the complex at these three potential load-bearing sites can be explained as follows: The decreased magnitude of functional load from a soft diet with a compressive strength of 0.3–0.5 N/mm could decrease PDL-collagen turnover rate due to decreased tooth movement relative to bone (37, 38). A decrease and/or loss of occlusal function demonstrated atrophy of the PDL, and was related to a loss in lower and higher molecular weight proteoglycans responsible for the structural maintenance and mechanical integrity of the PDL (39–48). The innervated PDL contains vasculature, various types of collagen (including types I, III, V, VI, and XII) and several noncollagenous proteins that contribute to the chemically bound fluid, maintenance of hydrostatic pressure, load regulation and dissipation, and is a provider of nutrients (49, 50). However, the innate birefringence of the PDL decreases significantly when the molecular structure of collagen is degraded as a result of decreased turnover due to inadequate loading (51–53). In this study, a strong PDL-birefringence was observed at all three anatomical locations of the complex subjected to higher loads (Fig.3C,3D) and what are considered to be normal functional loads for a rat, while a patchy, diffuse birefringence was observed in PDL subjected to lower functional loads (Figs.3A,3B). Fundamentally, enhancement of birefringence can only be observed when sirius red molecules are bound to oriented, highly organized collagen molecules (54). Hence, aberrations to functional loads can change the physiological program within PDL-cells, altering the biochemical events and structural and mechanical integrity of the PDL-matrix, thereby redefining the local events in the complex as observed in this study.

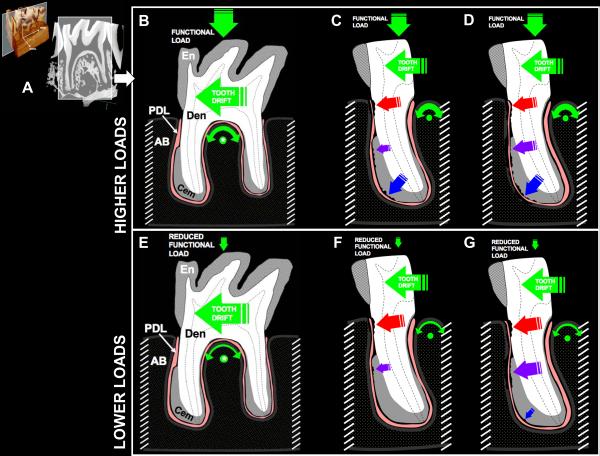

The current dogma states that the acellular PC is responsible for tooth attachment, while apical and cellular SC is responsible for resisting functional loads (19). However, the observed local changes in coronal and apical cementum, and corresponding bone and PDL could be considered as necessary adaptive responses to preserve the functional mechanics of the bone-tooth joint. These adapted sites can also be noted as local load-bearing sites within the bone-PDL-cementum complex of molars. The strains in the local load bearing sites of the bone-PDL-tooth complex are often broadly categorized as tensile and compressive strains due to widening and narrowing of the PDL-space within the complex. While this is true, other areas such as the endosteal and trabecular spaces within alveolar process are also stimulated by flow of interstitial fluid caused due to functional loads. In this study, as lower loads decreased tooth mobility and PDL strain resulting in a loss of PDL mechanical integrity, it can be hypothesized that the mechanobiological events prompted by integrin-based cell-matrix interaction at the PDL-cementum and PDL-bone attachment sites were altered (49), resulting in resorption of the bone and PC of the distal root. This observation was consistent, but to a lesser degree within the complex subjected to higher loads. Rather, higher loads transmit greater force to the apical region of the root, and as a result increased SC resorption was observed. While SC resorption in teeth subjected to lower loads was observed at earlier time points, the amount of resorption decreased over time (Fig.4B) indicating the adaptive effects of the reduced functional loads apically on the complex. Over time, reduced functional loads suppress activity of the masticatory muscles, decrease load across the facial skeleton (29), diminish apically directed compressive forces (55), and result in decreased SC resorption. This observation was consistent with models that illustrated a significant increase in SC with a decrease and or absence of functional loads (24, 56).

In this study, resorption sites were consistently observed in the coronal, middle, and apical regions of the distal side of M2/D in six-week-old rats probably due to innate distal drift as mentioned by others (24, 27, 57). However, when subjected to lower loads over time, the degree of resorption and resorption patterns were altered at the load-bearing sites. On the opposing side formed by bone, higher loads could have resulted in increased hydrostatic pressure within the endosteal and trabecular spaces (51, 52), resulting in adaptation of bone identified by reversal lines (Fig.5). At later time points, fewer changes in shape were observed in complexes subjected to lower loads (Figs.4, 5). These observations were similar to those reported by others on skeletal bone and alveolar bone (51, 52, 58–62).

Distal drift in rats could result in lower and higher X-ray attenuating areas due to trailing and leading envelopes in adapting bone around the tooth (Fig. 5). Although the trailing and leading edge effects are distinct in bone subjected to higher functional loads, it was less evident in bone subjected to lower loads in this study. The complex geometry of the tooth within the alveolar socket along with the trailing and leading envelopes due to distal drift could manifest into varying mineral gradients (Fig. 6) due to bone growth on the mesial side and bone resorption on the distal side, thus maintaining a uniform PDL-space at any time point.

Physical and chemical gradients are natural and exist between PDL-bone and PDL-cementum to optimally distribute functional loads (63). As a result of functional loads, the PDL continues to experience tensile and compressive strains within and at its attachment sites with bone and cementum (21). The varying strains in turn modulate the biochemical expressions through site-specific cells, which act as transducers (i.e. strain gauges) to either increase or decrease expression of biomolecules responsible for apposition or resorption of mineral in bone and cementum. However, no significant differences in intensity were observed in the mineral gradient at the PDL-bone and PDL-cementum interface sites (Fig.6), although higher attenuation of X-rays in cementum and bone subjected to higher loads (Figs. 6B and 6C) was observed. Some possible explanations for these observed effects are as follows: (i) the organic scaffold upon which mineralization occurred was better maintained in the complex that was normally loaded (51,52); (ii) the lower magnification at which the mineral changes were documented was accurate only for macro-scale events, and not sensitive to the micro-scale events within the mineralized tissues; (iii) in order to compare the gradient in cementum to that in bone, equal and limited distances of only 80 μm from the periodontal ligament attachment site into the respective hard tissues were measured; and (iv) the reduction in functional loads could have a moderate effect on bone and cementum mineral concentrations and may be confirmed by extending the study to later time points. Regardless, from a materials and mechanics perspective, the locally identified gradual increase in mineral at the PDL-bone and PDL-cementum interfaces could be to accommodate changes in functional loads. The combined effect of aforementioned loss in PDL-structural integrity and decreased distal drift of rat molars subjected to reduced functional loads could explain: 1) decreased apical resorption and 2) decreased X-ray attenuation in bone and cementum.

The increasing trend in X-ray attenuation can be related to the increase in the hardness values (Fig.7) of cementum and bone observed with age in both groups. During development, an increase in hardness with age is expected within groups, but the significant increase in hardness between groups at the 12 and 15 week time points can be related to the increase in X-ray attenuation and maintenance of the `quality' of bone and cementum. Functional mineralization is best understood by accounting for the interaction of mineral inside and outside the collagen fibrils that form the tissue scaffold (64, 65). However, a compromised mineral-collagen interaction commonly observed in inadequately loaded mineralized tissue could impair the overall `quality' of the mineralized tissue (51, 66). This could explain the significantly greater hardness (Fig.7) of bone and cementum subjected to higher loads when compared to inadequately loaded bone and cementum.

This study documents a specific adaptive mechanism of the complex (a reservoir of multiple cell types) originally accustomed to higher loads, suddenly “forced” to accommodate reduced loads that has not been previously shown by others. Summarizing with a biomechanical model (Fig.8), the reduced functional loads can cause a decrease in tooth rotation, lateral loads, and different stress states within the complex. As with any multi-rooted tooth, the molar could pivot or rotate using the interradicular bone as a fulcrum (67), and alter localized widening and narrowing of the PDL-space. This in turn could result in altered tensile and compressive strains of the PDL, and varying stress patterns at the PDL-bone and PDL-cementum attachment sites. Furthermore, the effects of reduced loads are more evident with time with distinct changes in resorption and mineralization patterns in the twelve- and fifteen-week groups (Figs.4 and 5). These results can be considered as necessary local adaptations of the complex to accommodate decreased functional loads and to maintain the functional efficiency.

Figure 8.

A) Virtual slice of M2 taken from a tomograph illustrating the bone-PDL-tooth complex. Schematic of a biomechanical model illustrating dominant forces on the second mandibular rat molar and resulting load-mediated adaptation of tissues in the complex subjected to higher and lower functional loads. B) The hard pellet diet provides a high functional load and apically directed forces in addition to the distally directed forces due to innate tooth drift. Together, these forces cause the tooth to rotate, with the inter-radicular bone as the fulcrum point (green dot). C, D) The rotation redirects the apical and distal forces, causing PDL compression between the alveolar bone and the tooth and resulting resorption in the coronal, midroot, and apical regions with time. E) The soft, powdered diet decreases the functional load, so that the distally directed forces of tooth drift dictate tooth movement. The anatomy of the inter-radicular bone also creates a fulcrum point (*) around which some rotational movement could exist. F) The distal tooth drift together with some rotation causes regional PDL compression between the alveolar bone and the coronal portion of the tooth, resulting in resorption. G) In the absence of substantive functional loading, the rotational force on the tooth is minimized, and little compressive force acts on the apical portion of the root. Meanwhile, subsequent tooth drift acts to translate the tooth distally, causing regional PDL compression between the alveolar bone and the tooth in the coronal and midroot regions. En = Enamel, Den = Dentin, Cem = Secondary Cementum, PDL = Periodontal Ligament, AB = Alveolar Bone.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, diet consistency affects the functional loads experienced within the tissues of the bone-tooth joint. Lower forces may not be sufficient to maintain tissue homeostasis, and could degrade collagen in the PDL, alter the distribution of stress-induced resorption, and result in lower `quality' bone and cementum. From a clinical translation perspective, this study provides insights into modulation of load on the complex for improved tooth function during periodontal disease and/or orthodontic and prosthodontic treatments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Peter Sargent, Department of Cell and Tissue Biology for the use of the ultramicrotome. Support was provided by Benjamin Dienstein Research Fund, UCSF; NIH/NIDCR R00 DE018212 (SPH), NIH/NCRR 1S10RR026645-01 (SPH); Strategic Opportunities Support (SOS) and T1 Catalyst Clinical and Translational Science Institute - CTSI University of California (SPH), Departments of Preventive and Restorative Dental Sciences and Orofacial Sciences, UCSF.

REFERENCES

- (1).Carter DR, Beaupre GS. Skeletal function and form. Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Nanci A, Bosshardt DD. Structure of periodontal tissues in health and disease. Periodontol 2000. 2006;40:11–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Ten Cate AR. Oral Histology Development, Structure, and Function. 5th edn. Mosby Year Book Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Woda A, Foster K, Mishellany A, Peyron MA. Adaptation of healthy mastication to factors pertaining to the individual or to the food. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Graf H. In: Occlusal forces and mandibular movements. Elmsford NY, editor. Pergamon Press, Inc.; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Graf H. A method for measurement of occlusal forces in three directions. Helvetica Odontologica Acta. 1974;18 [Google Scholar]

- (7).Graf H. Occlusal forces during function. University of Michigan Press; Ann Arbor, Michigan: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sako N, Okamoto K, Mori T, Yamamoto T. The hardness of food plays an important role in food selection behavior in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2002;133:377–382. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Grunheid T, Langenbach GE, Brugman P, Everts V, Zentner A. The masticatory system under varying functional load. Part 2: effect of reduced masticatory load on the degree and distribution of mineralization in the rabbit mandible. Eur J Orthod. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Vreeke M, Langenbach GE, Korfage JA, Zentner A, Grunheid T. The masticatory system under varying functional load. Part 1: structural adaptation of rabbit jaw muscles to reduced masticatory load. Eur J Orthod. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Hartsfield JK., Jr. Pathways in external apical root resorption associated with orthodontia. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2009;12:236–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2009.01458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hartsfield JK, Jr., Everett ET, Al-Qawasmi RA. Genetic Factors in External Apical Root Resorption and Orthodontic Treatment. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15:115–122. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Rugh JD, Harlan J. Nocturnal bruxism and temporomandibular disorders. Adv Neurol. 1988;49:329–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Picton DCA. Titling movements of teeth during biting. Archives of Oral Biology. 1962;7 doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(62)90003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Bosshardt DD, Selvig KA. Dental cementum: the dynamic tissue covering of the root. Periodontol 2000. 1997;13:41–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Saffar JL, Lasfargues JJ, Cherruau M. Alveolar bone and the alveolar process: the socket that is never stable. Periodontol 2000. 1997;13:76–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Frost HM. Wolff's Law and bone's structural adaptations to mechanical usage: an overview for clinicians. Angle Orthod. 1994;64:175–188. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1994)064<0175:WLABSA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Blau PJ, Lawn BR, American Society for Testing and Materials. Committee E-4 on Metallography. International Metallographic Society . Microindentation techniques in materials science and engineering : a symposium sponsored by ASTM Committee E-4 on Metallography and by the International Metallographic Society, Philadelphia, PA, 15–18 July 1984. International Metallographic Society; Philadelphia, PA: 1986. p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Nanci A. Ten Cate's Oral Histology: Development, Structure, and Function. 6th edn. Mosby; Saint Louis: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Benjamin M, Toumi H, Ralphs JR, Bydder G, Best TM, Milz S. Where tendons and ligaments meet bone: attachment sites (`entheses') in relation to exercise and/or mechanical load. J Anat. 2006;208:471–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Qian L, Todo M, Morita Y, Matsushita Y, Koyano K. Deformation analysis of the periodontium considering the viscoelasticity of the periodontal ligament. Dent Mater. 2009;25:1285–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hiiemae K. Mechanisms of food reduction, transport and deglutition: how the texture of food affects feeding behavior. Journal of Texture Studies. 2004;35:171–200. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hiiemae KM. Masticatory function in the mammals. J Dent Res. 1967;46:883–893. doi: 10.1177/00220345670460054601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Schneider BJ, Meyer J. Experimental Studies on the Interrelations of Condylar Growth and Alveolar Bone Formation. Angle Orthod. 1965;35:187–199. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1965)035<0187:ESOTIO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Ohshima S, Komatsu K, Yamane A, Chiba M. Prolonged effects of hypofunction on the mechanical strength of the periodontal ligament in rat mandibular molars. Arch Oral Biol. 1991;36:905–911. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(91)90122-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kumazawa M, Kohsaka T, Yamasaki M, Nakamura H, Kameyama Y. Effect of traumatic occlusion on periapical lesions in rats. J Endod. 1995;21:372–375. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80973-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bondevik O. Tissue changes in the rat molar periodontium following alteration of normal occlusal forces. Eur J Orthod. 1984;6:205–212. doi: 10.1093/ejo/6.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Nakamura Y, Noda K, Shimoda S, et al. Time-lapse observation of rat periodontal ligament during function and tooth movement, using microcomputed tomography. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30:320–326. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kawakami T, Takise S, Fuchimoto T, Kawata H. Effects of masticatory movement on cranial bone mass and micromorphology of osteocytes and osteoblasts in developing rats. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2009;18:96–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Tanaka E, Sano R, Kawai N, et al. Effect of food consistency on the degree of mineralization in the rat mandible. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35:1617–1621. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).ElDeeb ME, Andreasen JO. Histometric study of the effect of occlusal alteration on periodontal tissue healing after surgical injury. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1991;7:158–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1991.tb00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kingsmill VJ, Boyde A, Davis GR, Howell PG, Rawlinson SC. Changes in bone mineral and matrix in response to a soft diet. J Dent Res. 2010;89:510–514. doi: 10.1177/0022034510362970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Bresin A, Kiliaridis S, Strid KG. Effect of masticatory function on the internal bone structure in the mandible of the growing rat. Eur J Oral Sci. 1999;107:35–44. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836.1999.eos107107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ho SP, Goodis H, Balooch M, Nonomura G, Marshall SJ, Marshall G. The effect of sample preparation technique on determination of structure and nanomechanical properties of human cementum hard tissue. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4847–4857. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).ASTM . E 384-99: Standard test method for microindentation hardness of materials. American Standard for Testing Materials International; West Conshohocken, PA: [Google Scholar]

- (36).Thomas NR, Peyton SC. An electromyographic study of mastication in the freely-moving rat. Arch Oral Biol. 1983;28:939–945. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(83)90090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Rippin JW. Collagen turnover in the periodontal ligament under normal and altered functional forces. II. Adult rat molars. J Periodontal Res. 1978;13:149–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1978.tb00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Rippin JW. Collagen turnover in the periodontal ligament under normal and altered functional forces. I. Young rat molars. J Periodontal Res. 1976;11:101–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1976.tb00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Kaneko S, Ohashi K, Soma K, Yanagishita M. Occlusal hypofunction causes changes of proteoglycan content in the rat periodontal ligament. J Periodontal Res. 2001;36:9–17. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2001.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Amemiya A. An electron microscopic study on the effects of extraction of opposed teeth on the periodontal ligament in rats. Jpn J Oral Biol. 1980:72–83. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Cohn SA. Disuse atrophy of the periodontium in mice following partial loss of function. Arch Oral Biol. 1966;11:95–105. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(66)90120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Cohn SA. Disuse atrophy of the periodontium in mice. Arch Oral Biol. 1965;10:909–919. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(65)90084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Gianelly AAaG HM. Biologic basis of orthodontics. Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Inoue M. Histological studies on the root-cementum of the rat molars under hypofunctional condition. J Jpn Prosthodont Soc. 1961:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Kinoshita Y, Tonooka K, Chiba M. The effect of hypofunction on the mechanical properties of the periodontium in the rat mandibular first molar. Arch Oral Biol. 1982;27:881–885. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(82)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Koike K. The effects of loss and restoration of occlusal function on the periodontal tissues of rat molar teeth: histopathological and histometrical investigation. J Jpn Soc Periodont. 1996:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Kronfeld R. Histologic study of the influence of function on the human periodontal membrane. J Am Dent Assoc. 1931:1242–1274. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Saeki M. Experimental disuse atrophy and its repairing process in the periodontium of rat molar. J Stomatol Soc Jpn. 1959:317–347. [Google Scholar]

- (49).McCulloch CA, Lekic P, McKee MD. Role of physical forces in regulating the form and function of the periodontal ligament. Periodontol 2000. 2000;24:56–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2240104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Berkovitz BKB, Moxham BJ, Newman HN. The Periodontal ligament in health and disease. 1st edn. Pergamon Press; Oxford; New York: 1982. p. xiv.p. 470. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Robling AG, Castillo AB, Turner CH. Biomechanical and molecular regulation of bone remodeling. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;8:455–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Robling AG, Turner CH. Mechanical signaling for bone modeling and remodeling. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2009;19:319–338. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v19.i4.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Krishnan V, Davidovitch Z. On a path to unfolding the biological mechanisms of orthodontic tooth movement. J Dent Res. 2009;88:597–608. doi: 10.1177/0022034509338914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Junqueira LC, Bignolas G, Brentani RR. Picrosirius staining plus polarization microscopy, a specific method for collagen detection in tissue sections. Histochem J. 1979;11:447–455. doi: 10.1007/BF01002772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Liu ZJ, Ikeda K, Harada S, Kasahara Y, Ito G. Functional properties of jaw and tongue muscles in rats fed a liquid diet after being weaned. J Dent Res. 1998;77:366–376. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770020501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Holliday S, Schneider B, Galang MT, et al. Bones, teeth, and genes: a genomic homage to Harry Sicher's “Axial Movement of Teeth”. World J Orthod. 2005;6:61–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Bondevik O. Tissue changes in the rat molar periodontium following application of intrusive forces. Eur J Orthod. 1979;2:41–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Frost HM. Bone remodelling dynamics. Thomas; Springfield, Ill.: 1963. p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Frost HM. Bone modeling and skeletal modeling errors. Thomas; Springfield, Ill.: 1973. p. ix.p. 214. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Frost HM. Obesity, and bone strength and “mass”: a tutorial based on insights from a new paradigm. Bone. 1997;21:211–214. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Jee WS, Frost HM. Skeletal adaptations during growth. Triangle. 1992;31:77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Roberts WE, Huja S, Roberts JA. Bone modeling: biomechanics, molecular mechanisms, and clinical perspectives. Seminars in orthodontics. 2004;10:123–161. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Ho SP, Kurylo MP, Fong TK, et al. The biomechanical characteristics of the bone-periodontal ligament-cementum complex. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6635–6646. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Balooch M, Habelitz S, Kinney JH, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW. Mechanical properties of mineralized collagen fibrils as influenced by demineralization. J Struct Biol. 2008;162:404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Landis WJ. A study of calcification in the leg tendons from the domestic turkey. J Ultrastruct Mol Struct Res. 1986;94:217–238. doi: 10.1016/0889-1605(86)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Gupta HS, Seto J, Wagermaier W, Zaslansky P, Boesecke P, Fratzl P. Cooperative deformation of mineral and collagen in bone at the nanoscale. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17741–17746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604237103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Chattah NL. Design strategy of minipig molars using electronic speckle pattern interferometry: comparison of deformation under load between the tooth-mandible complex and the isolated tooth. Advanced Materials. 2008;20:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- (68).Mavropoulos A, Kiliaridis S, Bresin A, Ammann P. Effect of different masticatory functional and mechanical demands on the structural adaptation of the mandibular alveolar bone in young growing rats. Bone. 2004;35:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.