Abstract

We have previously demonstrated that selectively-bred High (bHR) and Low (bLR) novelty-seeking rats exhibit agonistic differences, with bHRs acting in a highly aggressive manner when facing homecage intrusion. In order to discover the specific neuronal pathways responsible for bHRs’ high levels of aggression, the present study compared c-fos mRNA expression in several forebrain regions of bHR/bLR males following this experience. bHR/bLR males were housed with female rats for two weeks, and then the females were replaced with a male intruder for 10 min. bHR/bLR residents were subsequently sacrificed by rapid decapitation, and their brains were removed and processed for c-fos in situ hybridization. Intrusion elicited robust c-fos mRNA expression in both phenotypes throughout the forebrain, including the septum, amygdala, hippocampus, cingulate cortex, and the hypothalamus. However, bHRs and bLRs exhibited distinct activation patterns in select areas. Compared to bHR rats, bLRs expressed greater c-fos in the lateral septum and within multiple hypothalamic nuclei, while bHRs showed greater activation in the arcuate hypothalamic nucleus and in the hippocampus. No bHR/bLR differences in c-fos expression were detected in the amygdala, cortical regions, and striatum. We also found divergent 5-HT1A receptor mRNA expression within some of these same areas, with bLRs having greater 5-HT1A, but not 5-HT1B, receptor mRNA levels in the septum, hippocampus and cingulate cortex. These findings, together with our earlier work, suggest that bHRs exhibit altered serotonergic functioning within select circuits during an aggressive encounter.

Keywords: c-fos, bred High Responder (bHR), bred Low Responder (bLR), septum, hypothalamus, hippocampus, aggression, resident-intruder test, serotonin, 5-HT1A receptor, 5-HT1B receptor

1. Introduction

Aggression is a common behavior naturally expressed in response to threat or other environmental challenges. While aggression may be appropriate in some instances and important for an organism’s survival, extreme or uncontrollable aggression is maladaptive. Impulsive aggression is a common symptom of several mental illnesses, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, and some mood disorders (Davidson et al., 2000). Therefore, there is great interest in understanding genetic and biological factors that may predispose certain individuals to be more aggressive than others.

Previous studies using laboratory rats and mice have bred animals with either naturally high or low levels of aggression, indicating that aggressive behavior is strongly influenced by genetics (e.g. (Veenema and Neumann, 2007). In recent years, our research group developed two lines of Sprague-Dawley rats based on innate differences in emotional or environmental reactivity (Stead et al., 2006). Our selectively-bred High Responder (bHR) rats are hyperactive and vigorously explore novel environments, exhibit elevated impulsivity (Flagel et al., 2010) and enhanced psychostimulant self-adminstration (Davis et al., 2008) compared to bred Low Responder (bLR) rats. bLRs, on the other hand, are behaviorally inhibited, showing much less novelty-induced locomotor activity and exaggerated anxiety- and depression- like behavior compared to bHR animals (Clinton et al., 2008; Stead et al., 2006). More recently we found that bHR rats exhibit greater inter-male aggression compared to bLRs in the resident-intruder paradigm (see companion paper, Kerman, Clinton et al., 2011). When an intruder is introduced into the homecage, bHR animals react by aggressively sniffing, attacking and biting the intruder rat, while bLRs are much more passive and sometimes even submissive to the intruder (see companion paper, Kerman, Clinton et al., 2011). These divergent behaviors were accompanied by hormonal differences, with bHRs showing enhanced corticosterone and testosterone secretion following intrusion compared to bLRs. Furthermore, these differences appear to be linked to underlying bHR/bLR differences in serotonin (5-HT) circuits, since we found both baseline and intrusion-evoked gene expression differences within several brainstem 5-HTergic nuclei (see companion paper, Kerman, Clinton et al., 2011). Based on these findings, we hypothesize activation of specific forebrain circuits in bHR/bLR rats following homecage intrusion, which may contribute to their markedly different behavioral and hormonal responses. In the present study we utilized c-fos mRNA expression as a marker of neuronal activation to identify the pattern of forebrain activation in bHR/bLR males following homecage intrusion experience.

Abundant clinical and preclinical evidence indicates that perturbed 5-HT neurotransmission plays an important role in regulating aggressive behavior (Miczek et al., 2007). Several studies point to deficient 5-HTergic transmission precipitating an aggressive state, including observations of reduced 5-HT metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid of aggressive rodents (Giacalone et al., 1968), monkeys (Higley et al., 1992; Westergaard et al., 1999), and humans (Brown et al., 1979; Kruesi et al., 1990), as well as enhancement of aggressive behavior following diet-induced tryptophan depletion (Delgado et al., 1990; Pihl et al., 1995). Our previous results suggest that bHRs’ aggressive tendencies may stem from a deficiency within certain 5-HTergic cell groups. Thus, a second aim of the present study is to examine 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B mRNA receptor expression in several forebrain terminal regions known to receive 5-HT projections.

2. Results

2.1 Homecage intrusion-induced c-fos mRNA expression

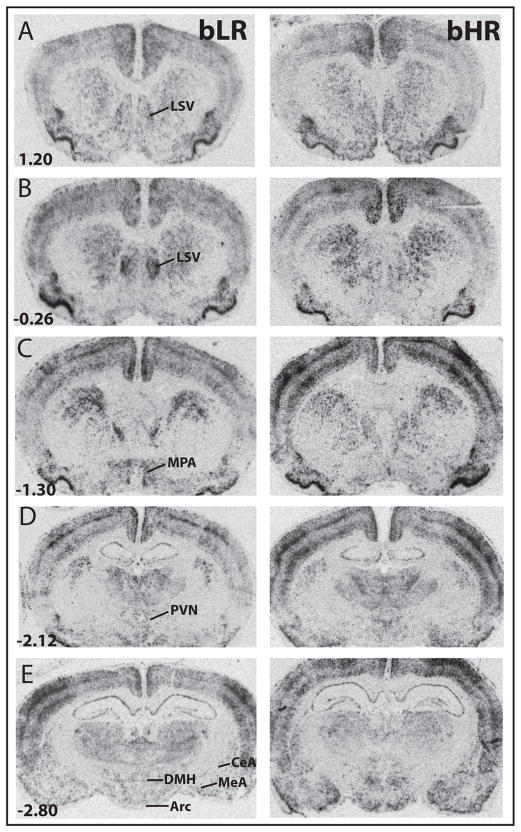

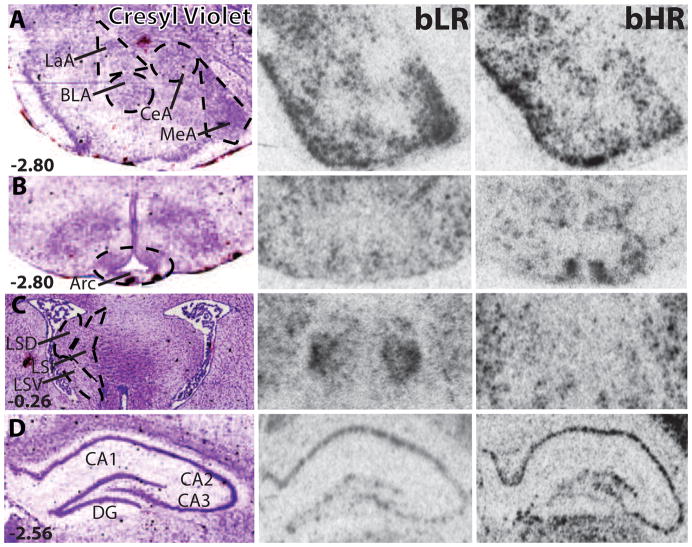

We previously found that bHR males exhibit greater aggressive behavior than bLRs when facing homecage intrusion (see companion paper, Kerman, Clinton et al., 2011). The present study evaluated expression of the immediate early gene c-fos as an indicator of forebrain regional activation following exposure to the resident-intruder paradigm (Fig. 1). Robust c-fos mRNA expression was detected throughout the forebrain of bHR/bLR resident males at 15 min. following initiation of intruder exposure, with robust expression within the lateral septum (LS), amygdala, several hypothalamic nuclei, the piriform cortex (Pir), cingulate cortex (Cg), motor cortex (M1,2), caudate putamen (CPu), nucleus accumbens (Acc), and the hippocampus (Cornu Ammonis fields CA1–CA3, and the dentate gyrus (DG)) (Fig. 2). Closer inspection of these data revealed heterogeneous c-fos expression, which was confined to specific subregions within several of these brain areas (Fig. 3).

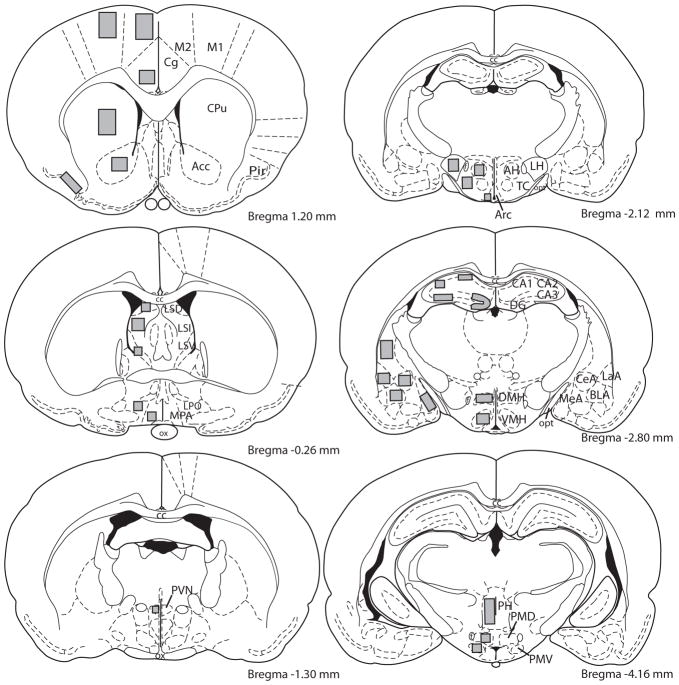

Figure 1.

Location of templates used to sample integrated optical density measurements within specific brain regions. Abbreviations: Acc - nucleus accumbens; AH - anterior hypothalamus; Arc - arcuate nucleus; BLA - basolateral amygdala; cc – corpus callosum; CeA - central amygdala; Cg - cingulate cortex; CPu – caudate-putamen; DG - dentate gyrus; DMH - dorsomedial hypothalamus; f fornix; LaA - lateral amygdala; LH - lateral hypothalamus; LPO - lateral preoptic area; LSD - dorsal lateral septal nucleus; LSI - intermediate lateral septal nucleus; LSV - ventral lateral septal nucleus; M1,2 - motor cortex 1 and 2; MeA - medial amygdala; MPA - medial preoptic area; opt – optic tract; ox – optic chiasm; PH - posterior hypothalamus; Pir - piriform cortex; PMD - dorsal premammillary nucleus; PMV - ventral premammillary nucleus; PVN - paraventricular nucleus; TC - tuber cinereum; VMH - ventromedial hypothalamus.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs from X-ray films illustrating the distribution of c-fos mRNA within several forebrain regions from Selectively-bred High Reponder (bHR) and bred Low Responder (bLR) rats. Coronal brain sections are arranged in a rostrocaudal sequence (A, most rostral through E, most caudal), with a representative bLR brain shown in the left column and bHR brain shown at right. Homecage intrusion evoked robust mRNA expression in several brain regions, including the lateral septum, ventral portion (LSV), medial preoptic area (MPA), paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH), arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (Arc), and the central (CeA) and medial amygdala (MeA).

Figure 3.

High-power photomicrographs of cresyl violet-stained sections (left column) and similar sections processed for in situ hybridization to detect c-fos mRNA expression in a representative bLR and bHR rat (middle and right columns, respectively). C-fos levels were assessed within multiple amygdalar nuclei, including: lateral (LaA), basolateral (BLA), central (CeA), and medial (MeA; A). The arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (Arc) was one hypothalamic region where we observed greater c-fos expression in bHR rats compared to bLRs (B). Three subdivisions of the lateral septum (LS) were analyzed: the dorsal (LSD), ventral (LSV), and intermediate (LSI; C). C-fos mRNA levels were also assessed in 4 subregions of the hippocampus: Cornu Ammonis fields CA1–CA3 and the dentate gyrus (DG) (D).

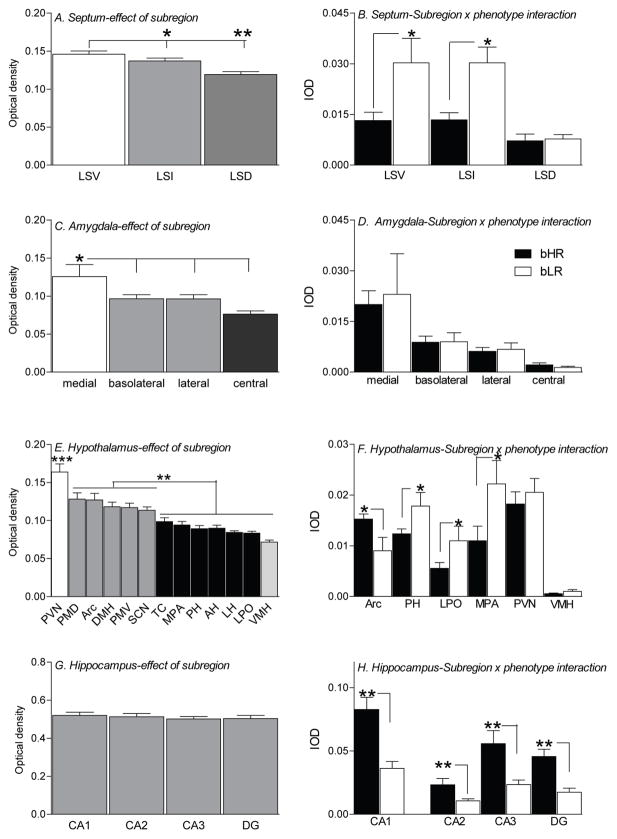

Using a 1-way ANOVA, we examined c-fos expression patterns across subregions of the LS by combining optical density data from bHR and bLR animals. This analysis revealed a main effect of subregion in the LS (F(2,24) =6.29, p<0.01), with the ventral portion of the LS (LSV) showing greater c-fos levels compared to the intermediate (LSI; p<0.05) and dorsal (LSD; p<0.01) parts (Fig. 4A). We then analyzed integrated optical density (IOD) measurements via a 2-way ANOVA to examine the effects of subregion and bHR/bLR phenotype. Here we found a main effect of phenotype (F(1,21) =15.35, p<0.001), subregion (F(2,21) =10.58, p<0.001), and a significant phenotype × subregion interaction (F(2,21) =3.48, p<0.05). Post hoc analyses showed that bLRs exhibited greater c-fos expression in the LSV (p<0.01) and LSI (p<0.01) compared to bHRs (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Homecage intrusion elicted robust region-specific patterns of c-fos mRNA expression in multiple forebrain regions of bHR and bLR animals. The homecage intrusion experience differentially activated subdivisions of the lateral septum (LS), with the greatest activation within the ventral subdivision (LSV) and the least activation within the dorsal subdivision (LSD) (data collapsed across bHR and bLR groups; A). Compared to bHRs, bLR males exhibited greater c-fos mRNA expression in the intermediate and ventral portions of the lateral septum (LSI and LSV, respectively) following the homecage intrusion experience (B). Homecage intrusion also produced a nuclei-specific response in the amygdala, with the greatest activation occurring in the medial nucleus of the amygdala compared to the other nuclei (data collapsed across groups; C). Surprisingly, there were no bHR/bLR differences in c-fos expression within these nuclei (D). Of the thirteen hypothalamic nuclei examined, the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) showed the greatest activation compared to the other nuclei (data collapsed across groups; E). Abbreviations for the other hypothalamic nuclei are the same as those defined in Figure 1C. bLRs showed greater intrusion-evoked c-fos activation within the posterior hypothalamus (PH), lateral preoptic area (LPO), and medial preoptic area (MPA) compared to bHRs, although bHRs showed greater activation in the arcuate nucleus (Arc). There were no phenotypic differences in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) or ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) (F). Finally, while the intrusion experience produced robust activation of the hippocampus, all subregions showed similarly high levels of c-fos expression (data collapsed across groups; G). bHR animals exhibited greater overall c-fos activation across all hippocampal subfields compared to bLRs (H). *** -- p<0.001; ** -- p<0.01; * -- p<0.05.

Using a 1-way ANOVA, we also examined c-fos expression patterns across select nuclei of the amygdala by combining optical density data from bHR and bLR animals. We found a main effect of nuclei (F(3,36) =5.06, p<0.01), with greater activation in the medial amygdala (MeA) relative to the basolateral, lateral, and central (CeA) nuclei (p<0.05) (Fig. 4C). We then analyzed IOD measurements via a 2-way ANOVA to examine the effects of nuclei and bHR/bLR phenotype. Here we found a main effect of nuclei (F(3,29) =8.41, p<0.0001), but no effect of phenotype, and no phenotype × nuclei interaction (Fig. 4D).

Using a 1-way ANOVA, we examined c-fos expression patterns across select nuclei of the hypothalamus by combining optical density data from bHR and bLR animals. We found a main effect of nuclei (F(12,119) =18.42, p<0.0001), with the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) showing the greatest activation (p<0.0001 compared to all other nuclei). The ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) showed the least c-fos expression (p<0.05 compared to all nuclei except the lateral hypothalamus (LH) and lateral preoptic area (LPO)). The remaining nuclei can be roughly divided into two groups, with one group showing an intermediate to high level of c-fos (dorsal premammillary nucleus (PMD), arcuate nucleus (Arc), dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH), and ventral premammillary nucleus (PMV)), and the other group showing a comparatively lower activation level (tuber cinereum (TC), medial preoptic area (MPA), posterior hypothalamus (PH), anterior hypothalamus (AH), LH, and LPO; Fig. 4E). We then analyzed IOD measurements from the hypothalamus via a 2-way ANOVA to examine the effects of nuclei and bHR/bLR phenotype. Here we found a main effect of nuclei (F(12,106) =11.60, p<0.0001), a phenotype × nuclei interaction (F(12,106) =4.24, p<0.05), but not effect of phenotype. Post hoc analysis showed that bLRs exhibited greater c-fos expression in the PH, LPO, and MPA of the hypothalamus compared to bHRs, although bHRs had higher c-fos levels in the Arc nucleus compared to bLR (Fig. 4F).

Using a 1-way ANOVA, we examined c-fos expression patterns across the subregions of the hippocampus by combining optical density data from bHR and bLR animals. Here, there was no effect of subregion, with equivalent c-fos expression levels across the different regions (Fig. 4G). We then analyzed IOD measurements via a 2-way ANOVA to examine the effects of hippocampal subregion and bHR/bLR phenotype. Here we found a main effect of subregion (F(3,50) =16.64, p<0.0001, since the different areas differ in physical size), a main effect of phenotype (F(1,50) =48.55, p<0.0001), but no phenotype × nuclei interaction (Fig. 4H). Across all subregions of the hippocampus, bHRs showed greater c-fos levels.

Finally, we used a 1-way ANOVA to examine c-fos expression patterns across several other forebrain regions, including the Pir, Cg, motor cortex (M1,2), dorsal and ventral striatum. We found a main effect of brain area (F(39,4) =70.56, p<0.0001), with Pir showing the greatest activation compared to Cg, M1,2, CPu, and Acc (p<0.01), and with Cg and M1,2 showing greater activation compared to CPu and Acc (p<0.05; data not shown). We analyzed IOD measurements via 2-way ANOVA to examine the effects of brain region and bHR/bLR phenotype. Here we found no effects of brain region or phenotype, and no brain region × phenotype interaction.

2.2 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor mRNA expression in bHR versus bLR males

Abundant evidence points to abnormalities of 5-HT neurotransmission contributing to the neurobiology of aggressive behavior, and consistent with this notion recent results from our group suggest that altered activation of specific 5-HT circuits may contribute to bHRs’ exaggerated aggressive tendencies (see companion paper, Kerman, Clinton et al., 2011). Therefore in addition to evaluating neuronal activation within several forebrain areas following homecage intrusion, the present study also assessed expression of 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor mRNAs in the same brain regions.

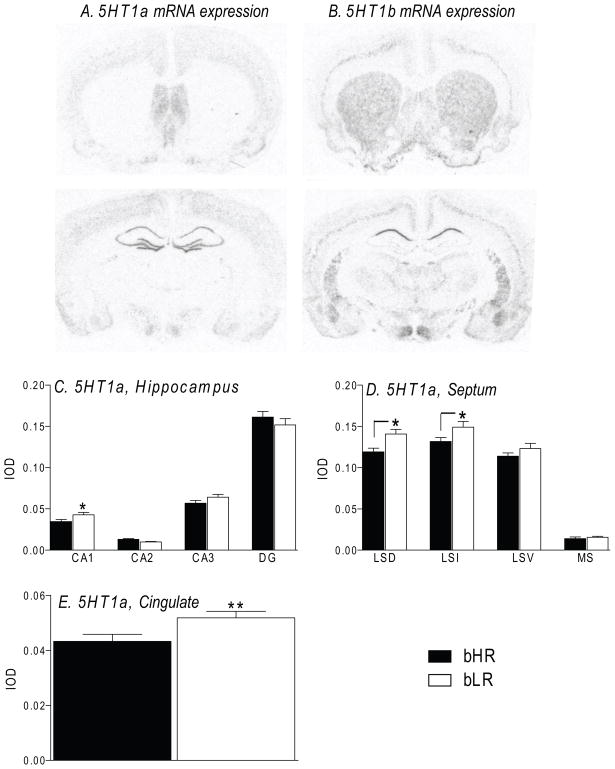

In situ hybridization to detect 5-HT1A receptor mRNA expression revealed a distribution pattern that is consistent with previous reports describing abundant labeling throughout several brain regions, including the hippocampus, neocortex, amygdala, and hypothalamus (Chalmers and Watson, 1991; Osterlund and Hurd, 1998); Fig. 5A). We compared bHR and bLR 5-HT1A receptor mRNA levels in several forebrain regions analyzed in the c-fos studies: Acc, CPu, Cg, hippocampus, LS, M1,2, and Pir. In the hippocampus, we performed a 2-way ANOVA, using subregion and bHR/bLR phenotype as independent factors. We saw a main effect of subregion (F(3,28) =45.74, p<0.0001), no effect of phenotype, but a phenotype × subregion interaction (F(3,28) =6.74, p<0.05). Post hoc analysis showed that bLRs exhibited higher 5HT1a expression in the CA1 region compared to bHRs (p<0.05; Fig. 5C). In the septum, we performed a 2-way ANOVA, using subregion and bHR/bLR phenotype as independent factors. We saw a main effect of subregion (F(3,28) =19.34, p<0.0001), no effect of phenotype, but a phenotype × subregion interaction (F(3,28) =11.18, p<0.01). Post hoc analysis showed that bLRs exhibited higher 5HT1a expression in the LSD and LSI compared to bHRs (p<0.05; Fig. 5D). Finally, we performed a 2-way ANOVA using brain region and bHR/bLR phenotype to examine 5-HT1A expression in several other brain areas – the striatum, cingulate, motor cortex and piriform cortex. For this, we found a main effect of brain area (F(5,33) =15.86, p<0.0001), no effect of phenotype, but a brain area × phenotype interaction (F(4,33) =3.80, p<0.05). Post hoc analysis showed that 5-HT1A mRNA levels were increased in the Cg of the bLR rats compared to bHRs (p<0.05; Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

bHR and bLR males exhibit differences in 5-HT1A receptor mRNA levels within select forebrain regions. Panels A and B depict photomicrographs from X-ray films illustrating the distribution of 5-HT1A receptor mRNA (A) and 5-HT1B receptor mRNA (B) within several forebrain regions. 5-HT1A receptor mRNA levels are particularly enriched in the septum and hippocampus (A), while 5-HT1B receptor mRNA is highly expressed in the caudate-putamen and the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus (B). We found increased 5-HT1A receptor mRNA expression in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (C), dorsal and intermediate portions of the lateral septum (LSD and LSI, respectively; D), and the cingulate cortex (E) in bLR animals compared to bHRs. There were no bHR/bLR differences in the expression of 5-HT1B receptor mRNA (data not shown). ** -- p<0.001; * -- p<0.05.

5-HT1B receptor mRNA expression was also consistent with previous reports, with the greatest levels apparent in Acc, CPu, CA1, and hypothalamus, and moderate expression in the septum and several cortical regions (Neumaier et al., 1996). We evaluated 5-HT1B receptor mRNA expression in the same brain areas analyzed for 5-HT1A receptor and c-fos. In the hippocampus, there was a main effect of subregion (F(3,28) =165.24, p<0.0001), but no effect of phenotype, and no subregion × phenotype interaction. In the septum, there was a main effect of subregion (F(2,21) =14.63, p<0.0001), but no effect of phenotype, and no subregion × phenotype interaction. For the remaining areas (cingulate, piriform cortex, motor cortex and striatum) there was a main effect of subregion (F(4,32) =45.65, p<0.0001), but no effect of phenotype, and no subregion × phenotype interaction (data not shown).

3. Discussion

We previously showed that exposure to homecage intrusion elicits markedly divergent behavioral and hormonal responses in bHR and bLR rats, with bHRs exhibiting exaggerated aggressive behavior, testosterone and corticosterone release, and diminished activation of select 5-HTergic brainstem nuclei (see companion paper, Kerman, Clinton et al., 2011). The present study revealed a distinct pattern of forebrain c-fos mRNA expression in bHR versus bLR animals following the homecage intrusion experience, suggesting that their behavioral and hormonal differences are accompanied, or perhaps driven by, activation of specific forebrain circuits. Several brain regions were activated in response to the homecage intrusion experience, with distinct septal, amygdalar, hypothalamic, and cortical subregions demonstrating increased c-fos mRNA levels. A number of these subregions also showed bHR/bLR differences in c-fos expression with bLR rats exhibiting greater activation of the LS and multiple hypothalamic nuclei in response to intrusion, whereas bHRs showed greater activation in the Arc and in the hippocampus. We also found divergent 5-HT1A receptor mRNA expression within some of these same areas, with bLRs having greater mRNA levels in the LS, hippocampus, and Cg. Taken together with our earlier work, these findings suggest that bHRs have altered 5-HTergic activation within select circuits during an aggressive encounter, which is consistent with reports of hyposerotonergic states contributing to aggressive behavior.

3.1 Neuroanatomy of Aggression

Our c-fos expression data indicate a distinct forebrain activation pattern in response to intruder exposure (Fig. 4). These data reveal a gradient so that LSV, PVN, MeA, and Pir exhibited particularly pronounced levels of c-fos. This activation pattern likely reflects complexity of the resident exposure experience. For example, social interaction is inherently stressful rodents (DeVries, 2002), and it reliably activates the PVN, a key stress-regulatory brain region (Sawchenko et al., 1996). Resident exposure also impacts the general level of arousal and anxiety, and activation of the LS has been implicated in these processes (Trent and Menard, 2010). Rats are also highly sensitive to olfactory cues, and intruder-elicited activation of Pir and MeA, both of which process olfactory stimuli (Gottfried, 2010; Price, 2003), likely represents strong olfactory stimulation by intruder presentation.

Interestingly, all of the brain regions that we examined showed a distinct pattern of c-fos expression within their subregions. For example, within the LS its ventral, intermediate, and dorsal subdivisions showed progressive decreases in c-fos. Likewise within the hypothalamus, PVN exhibited the greatest level of activation, while PMD, Arc, DMH, and PMV exibited intermediate levels, with TC, MPA, PH, AH, LH, LPO, and VMH showing the least amount of c-fos. In the amygdala, its basolateral and lateral subdivisions exhibited lesser c-fos levels than the medial subdivision, but greater levels than CeA. Among the other forebrain regions, Cg and M1,2 showed equivalent activation, which was less than Pir, but greater than that of the striatum. Together these data suggest that exposure to an intruder elicits a specific pattern of activation within the limbic system. It is likely that this pattern is specific to social interaction and may be different in response to other emotionally-salient stimuli, such as exposure to a novel environment or to chronic stress. Future studies will be required to test this notion.

Among examined brain regions several nuclei showed significantly greater c-fos levels in bLR rats, including: PH, LPO, MPA, LSI, and LSD, while Arc and the hippocampal subfields contained increased c-fos levels in bHRs. These data are consistent with previous reports implicating these brain regions in mediating aggressive behaviors. For example, diminished activation within the LS has been reported in aggressive rodents (Haller et al., 2006; Veenema and Neumann, 2007; Veenema et al., 2007). This brain region regulates diverse behaviors, including autonomic, sexual, and emotional responses, and it does so via its reciprocal projections to other limbic regions, including the olfactory bulb, hippocampus, amygdala, hypothalamus, and Cg (Mizumori et al., 2000; Risold and Swanson, 1997; Sheehan et al., 2000). Septal lesions produce the so-called “septal rage,” an effect that is driven by exaggerated fear and defensive behavior (Blanchard et al., 1979; Sheehan et al., 2000). Considering the role of the septum in modulating emotional behavior, it has been suggested that a suppression of its activity contributes to enhanced impulsiveness and aggressiveness (Siegel et al., 1999); thus, our current findings of reduced LS activation in bHRs may well underlie, at least in part, their impulsive and aggressive tendencies akin to what has been reported in other aggressive rodent models (Haller et al., 2006; Veenema and Neumann, 2007; Veenema et al., 2007).

In addition to the LS, multiple subregions of the hypothalamus have also been implicated in mediating aggressive behavior. Classic studies have delineated the hypothalamic attack area, which spans across multiple hypothalamic nuclei, including: AH, LH, VMH, and Arc (Hrabovszky et al., 2005). Electrical stimulation of this region elicits aggressive behavior in rats and other species, although specific types of aggressive behaviors seem to be linked to activation of its discreet subregions (Siegel et al., 1999). In contrast, activation of other hypothalamic subregions, such as medial hypothalamic areas, has been linked with defensive behavior (Bandler et al., 1985). Because of the bHR/bLR differences in aggressive behavior and in defensive freezing (see companion paper, Kerman, Clinton et al., 2011), the increased activation of Arc and decreased activation of MPA in bHR animals fits well with these previous observations.

Additionally, we also observed much greater c-fos expression across all hippocampal subfields (CA1-3 and DG) following the resident-intruder test. This finding fits well previous studies, which have reported increased hippocampal activation in highly aggressive mice (Haller et al., 2006) and have linked aberrant hippocampal activity with heightened aggression (Adamec and Stark-Adamec, 1983; Adamec, 1991; Ibi et al., 2008; Mellanby et al., 1981). Alternatively, the strong c-fos expression in the hippocampus may not have been dependent on aggression per se, and instead may have been more related to other aspects of behavioral arousal that accompany homecage intrusion, such as investigation of novel odor of the intruder male.

In addition to these differences in expression, bHR/bLR rats showed similar activation within several other forebrain regions, including the PVN, VMH, MeA, and CeA, which manifest enhanced activation following aggressive encounter in rats bred for low anxiety behavior (Veenema et al., 2007). Though bHR animals also manifest diminished anxiety-like behaviors and show similarly heightened aggressive responses, their different pattern of forebrain activation suggests that distinct neurobiological mechanisms may underlie aggression in animals selected for high novelty-seeking (i.e. bHR) as opposed to those selected for low anxiety. This notion is consistent with previous studies, which have found that a number of brain regions regulate aggressive behavior, and since aggression itself can manifest in numerous ways (i.e. defensive aggression, territorial aggression, etc.) (Miczek et al., 2007), it seems feasible that the nature of bHR/bLR aggression differences may due to differences in the activation of a unique set of forebrain limbic regions.

Although the resident-intruder paradigm is commonly used to test for aggressive tendencies, it is important to note that the home intrusion experience potentially elicits a wide range of behavioral responses, including fear and anxiety. One interpretation of our c-fos expression patterns in bHR versus bLR animals is that the activation of certain brain areas (i.e. hippocampus and Arc) and failure to activate other regions (i.e. LS) produces an exaggerated aggressive state, a finding that is generally consistent with other studies in aggressive rats and mice (Haller et al., 2006; Veenema and Neumann, 2007). However, an alternate explanation is that the observed c-fos expression differences may reflect increased behavioral inhibition (e.g. fear, anxiety) in bLRs facing intrusion. Our earlier work has demonstrated bLRs’ heightened anxiety in novel situations (Stead et al., 2006), so the observed c-fos expression differences may be related to bLRs’ increased anxiety or fear when facing the novel social encounter, as evidenced by their increased defensive freezing (see companion paper, Kerman, Clinton et al., 2011). Future efforts will explore these different possibilities.

3.2 Serotoningergic transmission and aggression

Abundant evidence supports the hypothesis of dysregulated 5-HT neurotransmission playing an important role in regulating aggressive behavior (Miczek et al., 2007). Findings of diminished 5-HT metabolites in cerebral spinal fluid of aggressive individuals (Brown et al., 1979; Giacalone et al., 1968; Kruesi et al., 1990) and of tryptophan-depleted diets leading to exaggerated aggressive behavior (Delgado et al., 1990; Pihl et al., 1995) suggest that a general 5-HT deficiency underlies enhanced aggression. Moreover, microdialysis studies have shed considerable light on the dynamic fluctuations of 5-HT during the course of aggressive encounters, revealing how levels change before, during and after an encounter, and how these patterns markedly vary across brain regions. For example, 5-HT levels in the prefrontal cortex, but not Acc, decline as an animal is actively engaged in an aggressive display (van Erp and Miczek, 2000), although 5-HT levels decrease in the Acc in anticipation of an impending fight (Ferrari et al., 2003). Our earlier study revealed diminished c-fos expression within specific 5-HT cell groups in bHR animals exposed to homecage intrusion, suggesting that deficient activation of this subset of 5-HT circuitry may contribute to their excessively aggressive behavior (see companion paper, Kerman, Clinton et al., 2011). Our present findings extend this work, showing regional and 5-HT receptor subtype-specific bHR/bLR differences that appear to involve 5-HT1A, but not 5-HT1B, receptors (at least in the forebrain regions assessed in this study). “Previous work has implicated both pre- and post-synaptic 5-HT1a and 5-HT1b receptors in the modulation of aggressive behavior, and each receptor subtype may contribute to unique aspects of aggression and/or mediate specific types of aggression (de Boer and Koolhaas, 2005). The present study focuses only on post-synaptic 5-TH1a and 5-HT1b receptors in the forebrain. We found significant bHR/bLR differences within select brain regions – the hippocampus, septum, and cingulate, and these differences were restricted to 5-HT1a mRNA. Other studies have demonstrated a role for both 5-HT1a and 5-HT1b in testosterone-mediated aggression (Simon et al., 1998), and 5-HT1b receptors in food restriction-induced aggressive behavior (Nakamura et al., 2008). Our findings suggest that bHRs’ aggression is solely mediated by 5-HT1a receptors within a subset of brain regions where this receptor subtype is particularly highly expressed. Importantly, the major source of 5-HT in these areas are the median and dorsal raphe (Lowry et al., 2008), brainstem regions that showed a very precise pattern of bHR/bLR gene expression differences and activation by intruder exposure (see companion paper, Kerman, Clinton, et al., 2011). Future efforts will examine serotonergic levels in bHR versus bLR brains both at baseline and at different points during the resident-intruder test. Additional pharmacological experiments will examine the effects of 5-HT1A receptor agonists (applied either systemically, or delivered locally into specific brain regions), to determine whether this can attenuate bHRs’ aggressive tendencies.

3.3. Conclusions

Aggressive behaviors can manifest in multiple ways, and it is likely that they are mediated by distinct neurobiological processes. In humans aggression frequently coexists with hyperactivity, impulsivity, and increased propensity for drug abuse, a behavioral profile that represents externalizing disorders (Brown et al., 1989; Brown and Linnoila, 1990; Kruesi et al., 1990; Westergaard et al., 1999; Westergaard et al., 2003). In these companion papers we demonstrate that bHR animals, which were selectively-bred for increased novelty-induced locomotion and that also manifest increased impulsivity together with an increased propensity for drug self-administration, exhibit heightened inter-male aggression. This behavioral response is accompanied by hormonal changes that are typical of aggression, as well as a distinct pattern of brain activation along with alterations in the expression of key genes that regulate 5-HTergic neurotransmission. These differences in brain activation and gene expression were restricted to specific brainstem and forebrain subregions, suggesting that functional alterations of specific 5-HT circuits mediate aggressive displays in animals with an inborn predisposition to heightened novelty-seeking, impulsivity, and drug self-administration.

4. Experimental Procedure

4.1 Animals

Adult male bHR and bLR males (n = 10 per group) were acquired from our in-house breeding colony where we have maintained these lines for several generations (Stead et al., 2006). bHR and bLR rats used in these studies were from the 22nd generation of our colony. In addition, a group of adult Sprague-Dawley male rats (n=20) was purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) and allowed to acclimate to our housing facilities for at least 1 week prior to any behavioral testing. All rats were housed in a dedicated animal facility with 12:12 light–dark cycle (lights on at 6 a.m.). Rat chow and water were available ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the University of Michigan University Committee on Use and Care of Animals, and were conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health (NIH) guidelines on laboratory animal use and care dictated by the National Research Council in 1996. All work was carried out in accordance with European Commission (EC) Directive 86/609/EEC for animal experiments and the Horizontal Legislation on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/chemicals/lab_animals/legislation_en.htm).

4.2 Resident-Intruder Paradigm

bHR/bLR males were housed with a female mating partner of the same selectively-bred line (i.e. male bHR with female bHR, and male bLR with female bLR) for 14 days. On the day of testing (day 15), the female partner was removed and each resident was presented for 10 min with a size-matched commercially-purchased male Sprague-Dawley rat classified as the intruder. Each intruder rat was only used once in the resident-intruder paradigm. This social encounter was videotaped, and subsequently scored for aggressive, defensive, and other non-antagonistic behaviors in resident and intruder rats, although those behavioral data were reported elsewhere (see companion paper, Kerman, Clinton et al., 2011).

4.3 Tissue collection and in situ hybridization

Five minutes following resident-intruder testing (15 minutes after beginning of testing) bHR/bLR resident animals were sacrificed by rapid decapitation. Brains were removed, snap frozen and stored at −80° C. They were cryostat sectioned at 12 μm, immediately thaw-mounted onto Fisherbrand Superfrost Plus Microscope Slides (Fisher Scientific, http://www.fishersci.com/), and subsequently prepared for in situ hybridization. The expression of c-fos, 5-HT1A receptor and 5-HT1B receptor mRNAs was assessed at 240 μm intervals throughout several forebrain regions. At each anatomical level, adjacent slides were processed for each of the three transcripts. An additional adjacent slide was stained with cresyl violet and was used to guide anatomical identification of the regions of interest.

Our in situ hybridization protocol has been previously described (Clinton et al., 2008). Briefly, sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 1 hour. The slides were then washed 5 min. × 3 in 2X SSC (300mM NaCl/30mM sodium citrate, pH 7.2). Next, the slides were placed in a solution containing acetic anhydride (0.25%) in triethanolamine (0.1 M), pH 8.0, for 10 min at room temperature, rinsed in distilled water, and dehydrated through graded ethanol washes (50%, 75%, 85%, 95%, and 100%). After air drying, adjacent tissue sections were hybridized overnight at 55°C with a 35S-labeled cRNA probes (see below). Following hybridization, coverslips were removed and the slides were washed with 2X SSC and incubated for 1 hour in RNaseA at 37°C, followed by multiple washes in increasingly stringent SSC solutions. Slides were then rinsed in distilled H2O, dehydrated through graded ethanol washes, air-dried, and apposed to Kodak XAR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Slides processed for c-fos, 5HT1A and 5HT1B were exposed to film for 7 days; this time was selected because it produced signal within the linear portion of the development curve for each probe for the brain regions of interest.

The following cRNA riboprobes were used: c-fos (alias Fos; NCBI reference sequence - X06769, pos. – 585–1,368); 5-HT1A (alias Htr1a; NCBI reference sequence – J05276, pos. – 333–1,241); 5-HT1B (alias Htr1b; NCBI reference sequence – X62944, pos. – 210–1,070). Specificity of labeling was confirmed by the absence of signal following hybridization with sense riboprobes generated for the same positions of the target mRNAs (data not shown). After the 7-day exposure period, autoradiograms were developed and digitized using a ScanMaker 1000XL Pro flatbed scanner (Microtek, Carson, CA) with LaserSoft Imaging software (AG, Kiel, Germany) at 1,600 dpi. Digitized images were analyzed using ImageJ Analysis Software for PC from NIH. Adjacent cresyl violet-stained sections were digitized at 1,600 dpi using Super CoolScan 4000 ED slide scanner (Nikon, http://www.nikon.com/). The cresyl violet-stained sections provided cytoarchitectonic information to guide the delineation of brain regions and sub-nuclei, particularly for subregions of the amygdala and hypothalamus.

4.4 Data analysis

In an effort to standardize measurements of in situ hybridization signal and optical density, we utilized a template for each brain region or sub-nucleus based on the shape and size of the region. Fig. 1 indicates the location and relative size of the templates; illustrations have been modified from the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). Using these templates, optical density measurements were collected for each brain region from the left and right sides of the brain (where possible) and/or from rostral–caudal sections spaced 240 μm apart. Optical density values were corrected for background, multiplied by the area sampled to produce the Integrated Optical Density (IOD) measurement, which was then averaged to produce a single data point for each brain region per animal. These data points were averaged per group and compared statistically.

We first evaluated general patterns of homecage intrusion-evoked c-fos expression (collapsing across bHR/bLR groups); for this we used a one-factor ANOVA and compared c-fos levels (optical density values) across subregions of LS, amygdala, hypothalamus, and hippocampus. The effect of bHR/bLR phenotype was determined by comparing the mean level of c-fos, 5-HT1A, and 5-HT1B mRNA within the same brain regions between intrusion-exposed bHR and bLR males using a two-factor ANOVA (bHR/bLR phenotype and sub-nucleus/subregion as independent factors and IOD as dependent factor when analyzing brain regions composed of multiple nuclei, such as the hypothalamus, septum, amygdala and hippocampus). Post-hoc comparisons were performed using Fisher’s Exact Test. Data were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Institute, http://www.spss.com/) and are presented as mean ± SEM. For all tests α=0.05.

Table 1.

| Brain region | bHR | bLR |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamus | ||

| AH | 0.829 ± 0.126 | 1.139 ± 0.362 |

| DMH | 0.879 ± 0.106 | 0.824 ± 0.136 |

| LH | 0.906 ± 0.229 | 0.926 ± 0.144 |

| PMD | 1.367 ± 0.169 | 1.387 ± 0.557 |

| PMV | 1.059 ± 0.187 | 1.002 ± 0.412 |

| PVN | 1.825 ± 0.271 | 2.054 ± 0.307 |

| SCN | 1.083 ± 0.193 | 1.125 ± 0.084 |

| TC | 0.616 ± 0.116 | 0.737 ± 0.252 |

| VMH | 0.056 ± 0.014 | 0.101 ± 0.038 |

| Amygdala | ||

| BLA | 0.898 ± 0.192 | 0.904 ± 0.292 |

| CeA | 0.225 ± 0.069 | 0.136 ± 0.037 |

| LaA | 0.607 ± 0.125 | 0.698 ± 0.205 |

| MeA | 1.988 ± 0.445 | 2.310 ± 1.390 |

| Forebrain | ||

| Acc | 3.493 ± 0.532 | 3.153 ± 0.653 |

| Cg | 11.234 ± 0.806 | 9.626 ± 1.634 |

| CPu | 12.252 ± 1.173 | 10.152 ± 2.291 |

| M1,2 | 9.985 ± 0.752 | 7.377 ± 1.660 |

| Pir | 12.114 ± 0.332 | 7.096 ± 0.819 |

Values represent average integrated optical density values ± standard errors × 100

Abbreviations: AH - anterior hypothalamus; DMH - dorsomedial hypothalamus; LH - lateral hypothalamus; PMD - dorsal premammillary nucleus; PMV - ventral premammillary nucleus; PVN - paraventricular nucleus; SCN - suprachiasmatic nucleus; TC - tuber cinereum; VMH - ventromedial hypothalamus; BLA - basolateral amygdala; CeA - central amygdala; LaA - lateral amygdala; MeA - medial amygdala; Acc - nucleus accumbens; Cg - cingulate cortex; CPu - caudate putamen; M1,2 - motor cortex 1 and 2; Pir - piriform cortex

Highlights.

Highlights for Clinton, Kerman et al “Distinct Forebrain Activation Patterns in Highly Aggressive Animals: Association with Genetic Predisposition to Novelty-Seeking”:

Our recent related work demonstrates high aggression in high novelty-seeking rats.

C-fos expression was used to identify neural activation following aggression.

Aggressive animals exhibit distinct activation in septum and hypothalamic nuclei.

Aggressive animals also show reduced serotonin-1a receptors in select brain regions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIMH 1K99MH085859 (SMC), NIMH 5K99MH081927 (IAK), NARSAD Young Investigator award (IAK), Office of Naval Research N00014-09-1-0598 (HA and SJW), and NIDA PPG 5P01DA021633-02 (HA and SJW). The authors would like to thank Ms. Sharon Burke and Ms. Sue Miller for their excellent technical assistance and Ms. Rebecca Simmons for helpful discussions of an earlier version of this manuscript. None of the funding sources had roles in study design; data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

There are no biomedical financial interests or conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adamec RE, Stark-Adamec C. Partial kindling and emotional bias in the cat: lasting aftereffects of partial kindling of the ventral hippocampus. I. Behavioral changes. Behav Neural Biol. 1983;38:205–22. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(83)90212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamec RE. Partial kindling of the ventral hippocampus: identification of changes in limbic physiology which accompany changes in feline aggression and defense. Physiology & Behavior. 1991;49:443–53. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90263-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandler R, Depaulis A, Vergnes M. Identification of midbrain neurones mediating defensive behaviour in the rat by microinjections of excitatory amino acids. Behav Brain Res. 1985;15:107–19. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(85)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ, Lee EM, Nakamura S. Defensive behaviors in rats following septal and septal--amygdala lesions. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1979;93:378–90. doi: 10.1037/h0077562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS, Kent TA, Bryant SG, Gevedon RM, Campbell JL, Felthous AR, Barratt ES, Rose RM. Blood platelet uptake of serotonin in episodic aggression. Psychiatry Res. 1989;27:5–12. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GL, Goodwin FK, Ballenger JC, Goyer PF, Major LF. Aggression in humans correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Res. 1979;1:131–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(79)90053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GL, Linnoila MI. CSF serotonin metabolite (5-HIAA) studies in depression, impulsivity, and violence. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(Suppl):31–41. discussion 42–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers DT, Watson SJ. Comparative anatomical distribution of 5-HT1A receptor mRNA and 5-HT1A binding in rat brain--a combined in situ hybridisation/in vitro receptor autoradiographic study. Brain Research. 1991;561:51–60. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90748-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinton S, Miller S, Watson SJ, Akil H. Prenatal stress does not alter innate novelty-seeking behavioral traits, but differentially affects individual differences in neuroendocrine stress responsivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:162–77. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, Larson CL. Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation--a possible prelude to violence. Science. 2000;289:591–4. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BA, Clinton SM, Akil H, Becker JB. The effects of novelty-seeking phenotypes and sex differences on acquisition of cocaine self-administration in selectively bred High-Responder and Low-Responder rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:331–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer SF, Koolhaas JM. 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor agonists and aggression: a pharmacological challenge of the serotonin deficiency hypothesis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526:125–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado PL, Charney DS, Price LH, Aghajanian GK, Landis H, Heninger GR. Serotonin function and the mechanism of antidepressant action. Reversal of antidepressant-induced remission by rapid depletion of plasma tryptophan. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:411–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810170011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AC. Interaction among social environment, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and behavior. Horm Behav. 2002;41:405–13. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari PF, van Erp AM, Tornatzky W, Miczek KA. Accumbal dopamine and serotonin in anticipation of the next aggressive episode in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:371–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Robinson TE, Clark JJ, Clinton SM, Watson SJ, Seeman P, Phillips PE, Akil H. An animal model of genetic vulnerability to behavioral disinhibition and responsiveness to reward-related cues: implications for addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:388–400. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacalone E, Tansella M, Valzelli L, Garattini S. Brain serotonin metabolism in isolated aggressive mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 1968;17:1315–27. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(68)90069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA. Central mechanisms of odour object perception. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:628–641. doi: 10.1038/nrn2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller J, Toth M, Halasz J, De Boer SF. Patterns of violent aggression-induced brain c-fos expression in male mice selected for aggressiveness. Physiology & Behavior. 2006;88:173–82. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley JD, Mehlman PT, Taub DM, Higley SB, Suomi SJ, Vickers JH, Linnoila M. Cerebrospinal fluid monoamine and adrenal correlates of aggression in free-ranging rhesus monkeys. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:436–41. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820060016002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrabovszky E, Halasz J, Meelis W, Kruk MR, Liposits Z, Haller J. Neurochemical characterization of hypothalamic neurons involved in attack behavior: glutamatergic dominance and co-expression of thyrotropin-releasing hormone in a subset of glutamatergic neurons. Neuroscience. 2005;133:657–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibi D, Takuma K, Koike H, Mizoguchi H, Tsuritani K, Kuwahara Y, Kamei H, Nagai T, Yoneda Y, Nabeshima T, Yamada K. Social isolation rearing-induced impairment of the hippocampal neurogenesis is associated with deficits in spatial memory and emotion-related behaviors in juvenile mice. J Neurochem. 2008;105:921–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruesi MJ, Rapoport JL, Hamburger S, Hibbs E, Potter WZ, Lenane M, Brown GL. Cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolites, aggression, and impulsivity in disruptive behavior disorders of children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:419–26. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810170019003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry CA, Evans AK, Gasser PJ, Hale MW, Staub DR, Shekhar A. Topographic organization and chemoarchitecture of the dorsal raphe nucleus and the median raphe nucleus. In: Monti JM, Pandi-Perumal SR, Jacobs BL, Nutt DJ, editors. Serotonin and Sleep: Molecular, Functional and Clinical Aspects. Birkhäuser Verlag; Switzerland: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mellanby J, Strawbridge P, Collingridge GI, George G, Rands G, Stroud C, Thompson P. Behavioural correlates of an experimental hippocampal epileptiform syndrome in rats. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981;44:1084–93. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.12.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Faccidomo SP, Fish EW, DeBold JF. Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology of Aggressive Behavior. In: Lajtha A, editor. Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology. Vol. Behavioral Neurochemistry, Neuroendocrinology and Molecular Neurobiology. Publisher Springer; US: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mizumori SJ, Cooper BG, Leutgeb S, Pratt WE. A neural systems analysis of adaptive navigation. Mol Neurobiol. 2000;21:57–82. doi: 10.1385/MN:21:1-2:057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Kikusui T, Takeuchi Y, Mori Y. Changes in social instigation- and food restriction-induced aggressive behaviors and hippocampal 5HT1B mRNA receptor expression in male mice from early weaning. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187:442–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumaier JF, Szot P, Peskind ER, Dorsa DM, Hamblin MW. Serotonergic lesioning differentially affects presynaptic and postsynaptic 5-HT1B receptor mRNA levels in rat brain. Brain Research. 1996;722:50–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MK, Hurd YL. Acute 17 beta-estradiol treatment down-regulates serotonin 5HT1A receptor mRNA expression in the limbic system of female rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;55:169–72. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pihl RO, Young SN, Harden P, Plotnick S, Chamberlain B, Ervin FR. Acute effect of altered tryptophan levels and alcohol on aggression in normal human males. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;119:353–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02245849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL. Comparative aspects of amygdala connectivity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;985:50–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risold PY, Swanson LW. Connections of the rat lateral septal complex. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;24:115–95. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawchenko PE, Brown ER, Chan RK, Ericsson A, Li HY, Roland BL, Kovacs KJ. The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and the functional neuroanatomy of visceromotor responses to stress. Prog Brain Res. 1996;107:201–22. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61866-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan TP, Cirrito J, Numan MJ, Numan M. Using c-Fos immunocytochemistry to identify forebrain regions that may inhibit maternal behavior in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114:337–52. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel A, Roeling TA, Gregg TR, Kruk MR. Neuropharmacology of brain-stimulation-evoked aggression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23:359–89. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(98)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NG, Cologer-Clifford A, Lu SF, McKenna SE, Hu S. Testosterone and its metabolites modulate 5HT1A and 5HT1B agonist effects on intermale aggression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1998;23:325–36. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(98)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stead JD, Clinton S, Neal C, Schneider J, Jama A, Miller S, Vazquez DM, Watson SJ, Akil H. Selective breeding for divergence in novelty-seeking traits: heritability and enrichment in spontaneous anxiety-related behaviors. Behav Genet. 2006;36:697–712. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent NL, Menard JL. The ventral hippocampus and the lateral septum work in tandem to regulate rats’ open-arm exploration in the elevated plus-maze. Physiol Behav. 2010;101:141–52. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Erp AM, Miczek KA. Aggressive behavior, increased accumbal dopamine, and decreased cortical serotonin in rats. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9320–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09320.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenema AH, Neumann ID. Neurobiological mechanisms of aggression and stress coping: a comparative study in mouse and rat selection lines. Brain Behav Evol. 2007;70:274–85. doi: 10.1159/000105491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenema AH, Torner L, Blume A, Beiderbeck DI, Neumann ID. Low inborn anxiety correlates with high intermale aggression: link to ACTH response and neuronal activation of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Horm Behav. 2007;51:11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard GC, Suomi SJ, Higley JD, Mehlman PT. CSF 5-HIAA and aggression in female macaque monkeys: species and interindividual differences. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:440–6. doi: 10.1007/pl00005489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard GC, Suomi SJ, Chavanne TJ, Houser L, Hurley A, Cleveland A, Snoy PJ, Higley JD. Physiological correlates of aggression and impulsivity in free-ranging female primates. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1045–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]