Abstract

The aim of this study was to critically analyze the effects of hydrogen peroxide on growth and survival of bacterial cells in order to prove or disprove its purported role as a main component responsible for the antibacterial activity of honey. Using the sensitive peroxide/peroxidase assay, broth microdilution assay and DNA degradation assays, the quantitative relationships between the content of H2O2 and honey’s antibacterial activity was established. The results showed that: (A) the average H2O2 content in honey was over 900-fold lower than that observed in disinfectants that kills bacteria on contact. (B) A supplementation of bacterial cultures with H2O2 inhibited E. coli and B. subtilis growth in a concentration-dependent manner, with minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC90) values of 1.25 mM/107 cfu/ml and 2.5 mM/107 cfu/ml for E. coli and B. subtilis, respectively. In contrast, the MIC90 of honey against E. coli correlated with honey H2O2 content of 2.5 mM, and growth inhibition of B. subtilis by honey did not correlate with honey H2O2 levels at all. (C) A supplementation of bacterial cultures with H2O2 caused a concentration-dependent degradation of bacterial DNA, with the minimum DNA degrading concentration occurring at 2.5 mM H2O2. DNA degradation by honey occurred at lower than ≤2.5 mM concentration of honey H2O2 suggested an enhancing effect of other honey components. (D) Honeys with low H2O2 content were unable to cleave DNA but the addition of H2O2 restored this activity. The DNase-like activity was heat-resistant but catalase-sensitive indicating that H2O2 participated in the oxidative DNA damage. We concluded that the honey H2O2 was involved in oxidative damage causing bacterial growth inhibition and DNA degradation, but these effects were modulated by other honey components.

Keywords: oxidative stress, hydrogen peroxide, bacteriostatic activity, honey, DNA degradation

Introduction

Hydrogen peroxide is generally thought to be the main compound responsible for the antibacterial action of honey (White et al., 1963; Weston, 2000; Brudzynski, 2006). Hydrogen peroxide in honey is produced mainly during glucose oxidation catalyzed by the bee enzyme, glucose oxidase (FAD-oxidoreductase, EC 1.1.3.4; White et al., 1963). The levels of hydrogen peroxide in honey are determined by the difference between the rate of its production and its destruction by catalases. Glucose oxidase is introduced to honey during nectar harvesting by bees. This enzyme is found in all honeys but its concentration may differ from honey to honey depending on the age and health status of the foraging bees (Pernal and Currie, 2000) as well as the richness and diversity of the foraged diet (Alaux et al., 2010). Catalases on the other hand, are of pollen origin. Catalase efficiently hydrolyzes hydrogen peroxide to oxygen and water due to its high turnover numbers. The total concentration of catalase depends on the amount of pollen grains in honey (Weston, 2000), and consequently, the hydrogen peroxide levels in different honeys may vary considerably (Brudzynski, 2006).

A substantial correlation has been found between the level of endogenous hydrogen peroxide and the extent of inhibition of bacterial growth by honey (White et al., 1963; Brudzynski, 2006). We have observed that in honeys with a high content of this oxidizing compound, bacteria cannot respond normally to proliferative signals and their growth remains arrested even at high honey dilutions. Pre-treatment of honey with catalase restored, to a certain extent, the bacterial growth, thus suggesting that endogenous H2O2 was implicated in the growth inhibition (Brudzynski, 2006).

Most of the conclusions on the H2O2 oxidizing action on bacteria are drawn from the simplified in vitro models, where direct effects of hydrogen peroxide on bacterial cells were analyzed. In contrast, honey represent complex chemical milieu consisting of over 100 different compounds (including antioxidants and traces of transition metals), where the interaction between these components and hydrogen peroxide may influence its oxidative action. We have recently unraveled that honey is a dynamic reaction mixture which facilitates and propagates the Maillard reaction (Brudzynski and Miotto, 2011b). The Maillard reaction which initially involves reaction between amino groups of amino acids or proteins with carbonyl groups of reducing sugars leads to a cascade of redox reactions in which several bioactive molecules are continuously formed and lost due to their cross-linking to other molecules (gain or loss of function; Brudzynski and Miotto, 2011b). We have shown that polyphenol-based melanoidins are a major group of Maillard reaction products possessing radical-scavenging activity (Brudzynski and Miotto, 2011a,b). These compounds are likely to interact with hydrogen peroxide and, depending of their concentration and redox capacity, either enhanced or diminished the oxidative activity of honey’s H2O2. In view of these facts, we hypothesized that the oxidizing action of honey’s hydrogen peroxide on bacterial cells may be modulated by the presence of other bioactive molecules in honey and therefore, may differ from the action of hydrogen peroxide alone.

Hydrogen peroxide is commonly used to disinfect and sanitize medical equipment in hospitals. For this purpose, the high concentrations of H2O2 in these disinfectants have to be maintained to overwhelmed defense systems of bacteria. At high concentrations, ranging from 3 to 30% (0.8 to 8 M), its bactericidal effectiveness has been demonstrated against several microorganisms including Staphylococcus-, Streptococcus-, Pseudomonas-species, and Bacillus spores (Rutala et al., 2008).Under these conditions, the bacterial cell death results from the accumulation of irreversible oxidative damages to the membrane layers, proteins, enzymes, and DNA (Davies, 1999, 2000; Rutala et al., 2008; Finnegan et al., 2010).

However, the hydrogen peroxide content in honey is about 900-fold lower (Brudzynski, 2006). Moreover, the literature data indicate that the cell death of cultured mammalian, yeast, and bacterial cells required H2O2 concentrations higher than 50 mM and was associated with chromosomal DNA degradation (Imlay and Linn, 1987a,b; Brandi et al., 1989; Davies, 1999; Bai and Konat, 2003; Ribeiro et al., 2006), which is still five to 10-fold higher then that observed in honeys. Therefore, we have undertaken this study to re-examined the role of hydrogen peroxide in antibacterial activity of honeys.

The hydrogen peroxide efficacy as an oxidative biocide is related to the bacterial sensitivity to peroxide stress. Defense mechanisms to oxidative stress varies between bacterial species such as Gram-negative E. coli and Gram-positive B. subtilis used in this study and depend on the growth phase (exponential- versus stationary-phase of growth), and on the adaptive and survival mechanisms (non-spore forming versus spore-forming bacteria; Dowds et al., 1987; Chen et al., 1995; Storz and Imlay, 1999; Cabiscol et al., 2000). In honey, the effects of H2O2 on the growth and survival of microorganisms may be mitigated or enhanced due to the presence of honey compounds. On one hand, a high content of sugars in honey that abstracts free water molecules from milieu inhibits bacterial growth and proliferation, but honey dilutions may create growth-supportive conditions due to the abundance of sugars as a carbon source for the growing cells. Hydrogen peroxide has deleterious effects on the growth and survival of bacterial cells but honey antioxidants such as catalases, polyphenols, Maillard reaction products, and ascorbic acid may lower the oxidative stress to cells and may have a protective effect against endogenous H2O2 (Brudzynski, 2006). Even less information exists on the mechanism of bactericidal action of honey’s hydrogen peroxide. The most fundamental and unsolved questions concerns the molecular targets of H2O2 cytotoxicity: does molecular hydrogen peroxide at concentrations present in honey cause DNA degradation?

During last decades, several honey compounds were identified as those implicated in honey antibacterial activity (for review, Irish et al., 2011). Despite this knowledge, the mechanisms by which these compounds lead to bacterial growth inhibition and bacterial death have never been explained or proven in biochemical terms. Since there is a persistent view that hydrogen peroxide is a main player in these events, the aim of this study was to critically analyze the effects of hydrogen peroxide on growth and survival of bacterial cells in order to prove or disprove its purported role as a main component responsible for the antibacterial activity of honey.

Materials and Methods

Honey samples

Honey samples included raw, unpasteurized honeys donated by Canadian beekeepers and two samples of commercial Active Manuka honey (Honey New Zealand Ltd., New Zealand, UMF 20+, and 25+; M and M2, respectively; Table 1) that were used as a reference in this study. During the study, honey samples were kept in the original packaging, at room temperature (22 ± 2°C) and in the dark.

Table 1.

Hydrogen peroxide concentrations in different honeys. Relationship between antibacterial activities of honey and hydrogen peroxide concentrations.

| Honey sample | Plant source | Hydrogen peroxide concentration (mM/l)* | E. coli MIC dilution (concentration) | B. subtilis MIC dilution (concentration) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M2 | Manuka (UMF 25) | 1.04 ± 0.17 | 16 (6.25%) | 16 (6.25%) |

| H58 | Buckwheat | 2.68 ± 0.04 | 16 (6.25%) | 8 (12.5%) |

| H23 | Buckwheat | 2.12 ± 0.22 | 8 (12.5%) | 4 (25%) |

| H20 | Sweet clover | 2.37 ± 0.03 | 8 (12.5%) | 4 (25%) |

| H11 | Wildflower/clover | 2.49 ± 0.03 | 8 (12.5%) | 8 (12.5%) |

| H56 | Blueberry | 0.52 ± 0.11 | 4 (25%) | 2 (50%) |

| H60 | Clover blend | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 4 (25%) | 2 (50%) |

| M | Manuka (UMF 20) | 0.72 ± 0.02 | 4 (25%) | 4 (25%) |

| H200 | Buckwheat | 0.248 ± 0.02 | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) |

| H203 | Buckwheat | 0.744 ± 0.01 | 4 (25%) | 4 (25%) |

| H204 | Buckwheat | 1.168 ± 0.05 | 4 (25%) | 4 (25%) |

| H205 | Buckwheat/alfalfa | 1.112 ± 0.02 | 4 (25%) | 4 (25%) |

*Hydrogen peroxide concentration was measured at honey dilution of 8× (25% v/v) and represent an average of three experimental trials, where each honey was tested in triplicate.

A stock solution of 50% (w/v) honey was prepared by dissolving 1.35 g honey (average density 1.35 g/ml) in 1 ml of sterile, distilled water warmed at 37°C. The stock solution was prepared immediately before conducting the antibacterial assays.

Preparation of artificial honey

Artificial honey was prepared by dissolving 76.8 g of fructose and 60.6 g of glucose separately in 100 ml of sterile, deionized water, and by mixing these two solutions in a 1:1 ratio. The osmolarity of the artificial honey was adjusted to that of the honey samples (BRIX) using refractometric measurements.

Bacterial strains

Standard strains of Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 14948; Thermo Fisher Scientific Remel Products, Lenexa, KS 66215) were grown in Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB; Difco Laboratories) overnight in a shaking water-bath at 37°C.

Overnight cultures were diluted with broth to the equivalent of the 0.5 McFarland Standard (approx.108 cfu/ml) which was measured spectrophotometrically at A600 nm.

Antibacterial assay

The antibacterial activity of honeys was determined using a broth microdilution assay using a 96-well microplate format. Serial twofold dilutions of honey were prepared by mixing and transferring 110 μl of honey with 110 μl of inoculated broth (106 cfu/ml final concentrations for each microorganism) from row A to row H of a microplate. Row G contained only inoculum and served as a positive control and row H contained sterile MHB and served as a blank.

After overnight incubation of plates at 37°C in a shaking water-bath, bacterial growth was measured at A595 nm using the Synergy HT multi-detection microplate reader (Synergy HT, Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

The contribution of color of honeys to the absorption was corrected by subtracting the absorbance values before (zero time) incubation from the values obtained after overnight incubation.

The absorbance readings obtained from the dose–response curves were used to construct growth inhibition profiles (GIPs). The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined from the GIPs and represented the lowest concentration of honey that inhibited the bacterial growth. The MIC end point in our experiments was honey concentration at which 90% bacterial growth reduction was observed as measured by the absorbance at A595 nm.

Statistical analysis and dose response curves were obtained using KC4 software (Synergy HT, Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

Hydrogen peroxide assay

Hydrogen peroxide concentration in honeys was determined using the hydrogen peroxide/peroxidase assay kit (Amplex Red, Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada). The assay was conducted in the 96-well microplates according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The fluorescence of the formed product, resorufin, was measured at 530 nm excitation and a 590 nm emission using the Synergy HT (Molecular Devices, BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) multi-detection microplate reader, and the dose–response curves were generated using the KC4™ data reduction software.

To calculate the hydrogen peroxide concentrations of the honeys, a standard curve was run alongside the honey serial dilutions. The standard curve was prepared from the 200 μM H2O2 stock solution. Each of the honey samples, and the standard curve, were tested in triplicate.

Catalase-treatment of honeys

Honey were treated with catalase (13 800 U/mg solid; Sigma-Aldrich, Canada) at ratio of 1000 units per 1 ml of 50% honey solution in sterile water for 2 h at room temperature.

Incubation of bacterial cultures with honey or hydrogen peroxide

Overnight cultures of E. coli and B. subtilis (1.5 ml, adjusted to 107 cfu/ml in MHB) were treated with either the 50% honey solution in a 1:1 ratio (v/v), an artificial honey solution, or with hydrogen peroxide solutions containing 5, 2.5, 1.2, 0.62, and 0.3125 mM (final concentrations) H2O2 prepared from the 20 mM stock solution. After overnight incubation at 37°C with continuous shaking, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,000×g (Eppendorf) for 30 s and then their DNA was isolated.

DNA isolation

The total genomic bacterial DNA was isolated from the untreated, control cells and from the honey- or hydrogen peroxide-treated cells using a DNA isolation kit (Norgen Biotek Corporation, St. Catharines, ON., Canada), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Agarose gel electrophoresis

Agarose gel (1.3%) electrophoresis was carried out in 1× TAE buffer containing ethidium bromide (0.1 μg/ml w/v). Ten microliters of DNA isolated from the untreated and treated bacterial cells was mixed with 5X loading dye (0.25% bromophenol blue, 0.25% xylene xyanol, 40% sucrose) and loaded into the gel. The DNA molecular weight markers selected were the HighRanger 1 kb DNA Ladder, MidRanger 1 kb DNA Ladder, and PCRSizer 100 bp DNA Ladder from Norgen Biotek (Thorold, Ontario). The gels were run at 85 V for 1 h and then visualized and photographed using the Gel Doc 1000 system and the Quantity One 1-D Analysis software (version 4.6.2 Basic) from Bio-Rad.

Results

Determination of the hydrogen peroxide concentrations in honeys

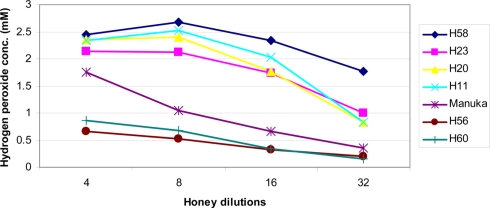

Formation of H2O2 depends on the honey dilution since glucose oxidase is inactive in undiluted honey (White et al., 1963; Brudzynski, 2006). Honeys used in this study required a four to 16-fold dilution for the maximal production of hydrogen peroxide to be observed (Figure 1). At the peak, H2O2 concentrations ranged from 2.68 ± 0.04 to 0.248 ± 0.02 mM in the different honeys (Table 1), as measured by a sensitive, high-throughput hydrogen peroxide/peroxidase assay (Amplex Red assay).

Figure 1.

Effect of honey dilutions on the production of hydrogen peroxide. Honeys of buckwheat origin, H58 and H23, together with sweet clover (H20), and wildflower/clover (H11) produced distinctively higher amounts of H2O2 than Manuka (M2) or honey blends (H56 and H60). The H2O2 content was measured in twofold serially diluted honeys, the x axis represents a log2 values.

Concentration-dependent effect of hydrogen peroxide on bacterial growth inhibition

Throughout this study, we used terms: endogenous hydrogen peroxide to describe H2O2 produced in honey by glucose oxidase and exogenous hydrogen peroxide, which has been added as a supplement to the bacterial cultures. These terms were introduced in order to differentiate between the effects of honey’s endogenous H2O2 whose action on bacterial cells could be modulated/obscured by other honey components as opposed to true, well-defined action of exogenous hydrogen peroxide directly added to bacterial culture.

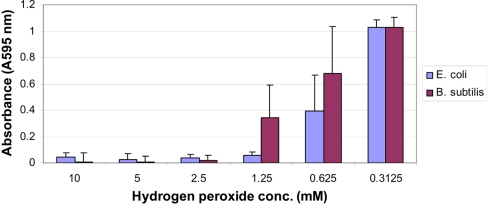

In agreement with previous reports (Brudzynski, 2006), we found a strong correlation between the content of honey hydrogen peroxide and the growth inhibitory action of Canadian honeys; honeys with high MIC90 values (6.25 to 12.5% v/v) corresponding to16 to 8× dilution) also possessed a high content of H2O2 (Table 1). Since the minimum inhibitory concentration values and the hydrogen peroxide peak were both observed at the 4 to 16× honey dilutions, we hypothesized that the maximal hydrogen peroxide production is required to achieve the bacteriostatic activity of honey at the MIC90 level. To test this assumption, we first examined the dose–response relationship between the concentration of exogenous hydrogen peroxide, ranging from 10 to 0.312 mM, and its growth inhibitory activity against E. coli and B. subtilis. The dose–response curves and growth inhibitory profiles revealed very reproducibly that H2O2 concentrations of 1.25 mM (1.25 μmoles/107 cfu/ml) and 2.5 mM (2.5 μmoles/107 cfu/ml) were required to inhibit the growth of E. coli and B. subtilis by 90%, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of increasing the concentration of exogenous hydrogen peroxide on the growth of E. coli (blue line) and B. subtilis (red line). Each point represents the mean and SD of three separate experiments conducted in triplicate.

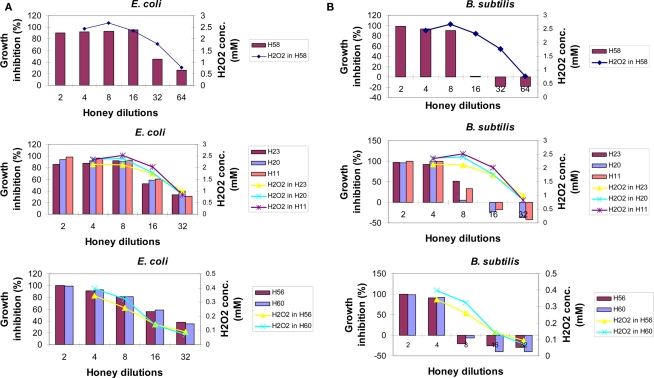

Relationship between the endogenous H2O2 content and the growth inhibitory activity of honeys

To investigate whether the content of honey H2O2 influences honey’s bacteriostatic potency in a similar manner to that of exogenous H2O2, each honey was analyzed for growth inhibitory activity and the production of hydrogen peroxide in the same range of honey dilutions. When the profiles of hydrogen peroxide production were superimposed on the growth inhibitory profiles of honeys against E. coli, it appeared that almost all of the bacteriostatic activity of honeys could be assigned to the effects of this compound (Figure 3A). In honeys, the endogenous H2O2 of 2.5 mM was of critical importance for the growth inhibition of E. coli; the dilutions that reduced H2O2 concentrations below this value showed a loss of honey potency to inhibit bacterial growth at the MIC90 level (Figure 3A). These data suggest that upon honey dilution, endogenous H2O2 mediates growth inhibition of E. coli. However, the concentrations required to reach MIC90 were twofold higher than that found for exogenous hydrogen peroxide (2.5 versus 1.25 mM, respectively; Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

The relationship between bacteriostatic effect of honey and the content of en-H2O2 on E. coli (A) or B. subtilis cultures (B) Growth inhibition profiles were determined for different honeys using the broth microdilution assay (columns). The content of honey H2O2 at each honey dilution was determined using the peroxide/peroxidase assay, as described in the Section “Materials and Methods.” Of note: growth inhibition profiles of artificial honey of osmolarity equal to that of natural honey provided MIC90 values of 25% (v/v) against both E. coli and B. subtilis. Each point or column represents the mean values of three separate experiments run in triplicate.

In contrast to E. coli, the inhibition of growth of B. subtilis seemed not to be due to the effect of the levels of honey H2O2 (Figure 3B). A rapid increase of B. subtilis growth with honey dilutions occurred despite the presence of high levels of H2O2 (honeys H58, H23, H20, and H11, Figure 3B). While exposure of the B. subtilis culture to exogenous H2O2 resulted in a concentration-dependent growth inhibition with MIC90 at 2.5 mM (Figure 2), comparable concentrations of H2O2 in honeys were ineffective. This indicated that other honey compounds/physical features were responsible for the growth inhibition, such as honey’s high osmolarity. Moreover, higher honey dilutions, beyond 16-fold, had a stimulatory effect on B. subtilis growth (Figure 3B).

Thus, our results demonstrated for the first time that bacteriostatic effects of endogenous versus exogenous hydrogen peroxide are markedly different due to the presence of other honey components and, more importantly, that the effects of honey H2O2 on bacterial growth are markedly different in E. coli and B. subtilis.

Comparison of effects of honey and hydrogen peroxide on DNA degradation in bacterial cells

To exert effectively its oxidative biocide action, the concentrations of hydrogen peroxide in various disinfectants are high ranging from 3 to 30% (0.8 to 8 M). In contrast, we have established that the average content of H2O2 in tested honeys ranged from 0.5 to 2.7 mM (Table 1). The concentrations of H2O2 measured in honeys, therefore was about 260–1600-fold lower than the effective bactericidal dose of H2O2 in disinfectants. Therefore, we asked the question whether hydrogen peroxide at concentrations present in honey can cause DNA degradation and ultimately bacterial cell death.

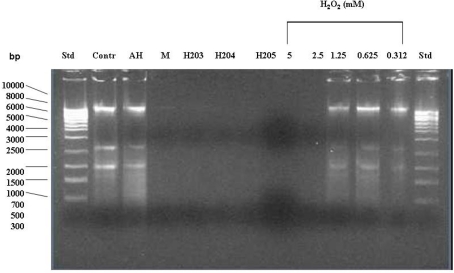

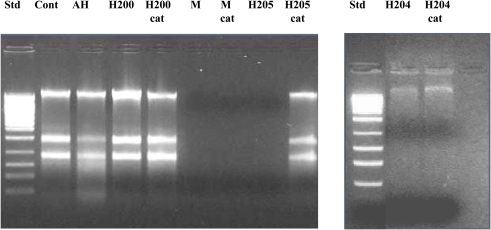

To examine the effects of honey and hydrogen peroxide on the integrity of bacterial DNA, E. coli cultures (107cfu/ml) were exposed to increasing concentrations of exogenous H2O2 (5–0.3125 mM) or to honeys containing known amounts of H2O2. After 24 h incubation at 37°C, bacterial DNA was isolated and its integrity examined on agarose gels. Figure 4 shows that the exposure of E. coli cultures to hydrogen peroxide at concentrations of 5 and 2.5 mM caused DNA degradation, while H2O2 concentrations lower than 2.5 mM were ineffective.

Figure 4.

Effect of exposure of E. coli cultures to honey or exogenous hydrogen peroxide on the integrity of bacterial DNA. The cells were treated with honeys (manuka, buckwheat honeys H203, H204, and H205) or with increasing concentrations of exogenous H2O2 (5–0.312 mM). Untreated cells and cells treated with the sugar solution (artificial honey, AH) served as the controls. The integrity of DNA was analyzed on agarose gels.

In contrast, honeys of relatively high H2O2 concentrations but below 2.5 mM (H203, 204, 205; Table 1) exerted DNA degrading activity (Figure 4). The ability of honeys H2O2 to degrade DNA appeared to be concentration-dependent. Honey H200 containing 0.25 mM H2O2 was unable to cleave DNA (Figure 5). The differences in the concentrations of H2O2 between exogenous and honey’s hydrogen peroxide that were required to effectively degrade chromosomal DNA may indicate that the action of honey H2O2 is enhanced by other honey components.

Figure 5.

Effect of exposure of E. coli cultures to honeys untreated and treated with catalase (cat) on the integrity of chromosomal DNA. “Cont” represents DNA isolated from untreated E. coli cells, AH-cell treated with artificial honey, or buckwheat honeys H200, H205, and M-manuka honey after 24 h incubation and H204 after 8 h incubation.

Manuka honey also possessed low concentration of H2O2 (0.72 mM), but efficiently degraded DNA (Figures 4 and 5). The antibacterial activity of manuka honey however is not regulated by the honey H2O2 content (Molan and Russell, 1988; Allen et al., 1991).

DNA degradation in E. coli cells exposed to catalase-treated or heat-treated honeys

To gain more insight into the role of H2O2 in chromosomal DNA degradation, E. coli cultures were exposed to honeys which were treated with catalase. Removal of H2O2 by catalase abolished DNA degrading activity of honey H205 and had a protective effect on bacterial DNA (Figure 5). The short incubation of catalase-treated honey H204 with DNA (8 h instead of 24 h) also prevented DNA degradation (Figure 5). Inactive honey H200 remained unable to degrade DNA after catalase-treatment (Figure 5). However, when honey H200 was supplemented with 2 mM H2O2, and then incubated with E. coli culture at 37°C for 8 h, it became active in degrading DNA and the extent of DNA degradation was comparable to that of honey H204 (Figure 5). On the other hand, catalase–treatment of manuka honey did not prevent DNA degradation, consistent with the notion, that manuka honey antibacterial activity is hydrogen peroxide-independent (Molan and Russell, 1988; Allen et al., 1991).

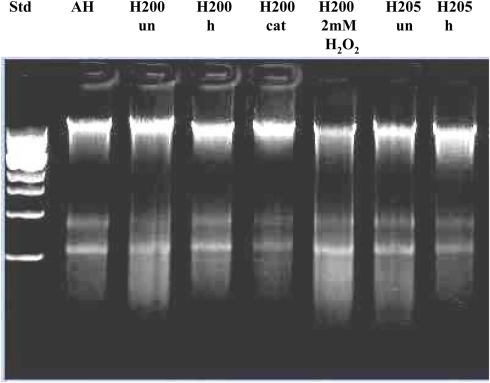

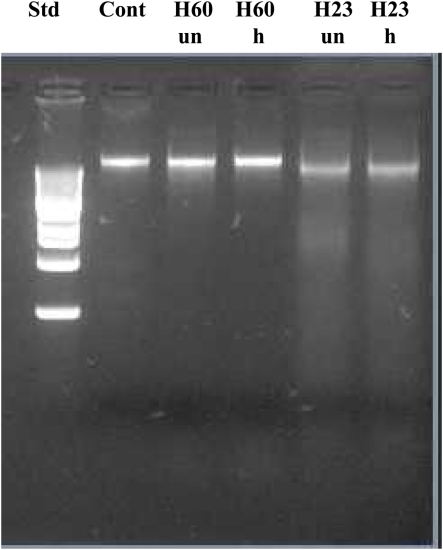

To investigate the potential involvement of DNases in DNA degradation, honeys were heat-treated under conditions which inactivate DNase activity (75°C for 10 min). Unheated and heat-treated honeys were then incubated with E. coli cultures at 37°C for 8 h, followed by DNA isolation and its analysis on agarose gels. Heat-treatment of active honeys H205 and H23 did not prevent DNA degradation suggesting against the involvement of DNase in this process (Figures 6 and 7). Moreover, the fact that some honeys displayed DNA degrading activity (H23 or H205) in bacterial culture while others did not (H200 and H60) makes it unlikely that this process was mainly due to the contamination of honeys with DNases. On the other hand, inability of honeys H200 and H60 to degrade DNA was closely related to the very low concentration of H2O2 in these honeys.

Figure 6.

Effect of exposure of E. coli cultures to heat-treated (h), catalase-treated (cat), and untreated (un) honeys on the integrity of chromosomal DNA. AH-cell treated with artificial honey, or buckwheat honeys H200, and H205. Lane “H200 2 mM H2O2” represents the effect of honey H200 supplementation with hydrogen peroxide on the E. coli DNA integrity.

Figure 7.

Effect of exposure of E. coli naked DNA to unheated and heat-treated honeys H60 and H23.

Together, these results provided a strong support for the role of H2O2 in DNA degradation.

Discussion

The findings described in this study revise the old views and provide novel information on the role of hydrogen peroxide in the regulation of bacteriostatic and bactericidal activities of honey.

Firstly, we found that the exponentially growing E. coli and B. subtilis cells were inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by exogenous H2O2 reaching MIC90 at 1.25 mM (1.25 μmoles/107 cfu/ml) and 2.5 mM (2.5 μmoles/107 cfu/ml), respectively. The bacteriostatic efficacy of H2O2 however differed significantly from that of honey H2O2. The main factors that contributed to these differences were (a) bacterial susceptibility/resistance to the oxidative action of hydrogen peroxide and (b) interference from other honey components.

Endogenous H2O2 inhibited the growth of E. coli in a concentration-dependent manner, but its MIC90 was twofold higher than those of exogenous H2O2 (2.5 versus 1.25 mM, respectively). The honeys MIC90 levels against E. coli coincided with the dilutions at which a peak of hydrogen peroxide production occurred. Treatment of honeys with catalase led to a significant reduction in their bacteriostatic activity (Brudzynski, 2006). Together, these data provide direct evidence that E. coli growth is sensitive to oxidative action of honey H2O2.

In contrast, growth inhibition of B. subtilis was not due to the action of honey H2O2. While exposure of B. subtilis cultures to H2O2 resulted in a concentration-dependent growth inhibition, the comparable concentrations of honey H2O2 in honey were ineffective in arresting B. subtilis growth. The rapid decrease in bacteriostatic activity of honey upon dilution was observed even in the presence of high concentrations of honey H2O2. These results suggest that other honey compounds were responsible for the inhibition of B. subtilis growth. As a consequence of growth arrest, the change in sensitivity of B. subtilis to honey H2O2 occurred. Instead of growth inhibition, we observed growth stimulation of B. subtilis at high honey dilutions (16-fold and over) and in the presence of high levels of H2O2. Literature data provides compelling evidence that transition from the exponential-phase growth to the stationary-phase growth evokes B. subiltis sporulation and with it, increased resistance to hydrogen peroxide. The transition to stationary-phase growth activates RNA polymerase σs transcriptional factor which regulates a stationary-phase gene expression of rpoS regulon. The expression of σs factor in B. subtilis evokes spore-formation to enhance bacterial survival (Dowds et al., 1987; Dowds, 1994; Loewen et al., 1998; Zheng et al., 1999; Chen and Schellhorn, 2003). Dowds et al. 1987 have shown that stationary-phase cultures of B. subtilis displayed viability even at the 10 mM concentration of H2O2. These data may explain, at least in part, an apparent insensitivity of B. subtilis to high levels of hydrogen peroxide in honey.

These results revealed significant differences in the sensitivities of E. coli and B. subtilis to oxidative stress caused by honey H2O2. As aerobic bacteria, both E. coli and B. subtilis are equipped with molecular machinery to cope with oxidative stress by activating several stress genes under oxyR- or perR-regulons, in E. coli and B. subtilis respectively (Dowds et al., 1987; Christman et al., 1989; Dowds, 1994; Bsat et al., 1998; Storz and Imlay, 1999). The oxyR and perR genes control expression of inducible forms of katG (catalase hydroperoxidase I, HP1), ahpCF (alkylhydroperoxide reductase) that function to reduce hydrogen peroxide to levels that are not harmful to growing cells (Hassan and Fridovich, 1978; Loewen and Switala, 1987; Storz et al., 1990; Seaver and Imlay, 2001). While these responses are similar in both bacteria, the main difference concerns their adaptive and survival mechanisms to oxidative stress.

Relatively little is known about the contribution of honey’s hydrogen peroxide to bacterial cell death. The most important result obtained in this work is the demonstration that honey H2O2 participated in bacterial DNA degradation. Several lines of evidence support this finding. Firstly, the treatment of exponential-phase E. coli cultures with increasing concentrations of exogenous hydrogen peroxide (5–0.3125 mM) or honeys of different content of endogenous H2O2 led to a concentration-dependent DNA degradation. While the minimum DNA degrading activity of exogenous H2O2 occurred at 2.5 mM (2.5 μmoles/107 cfu/ml), in contrast, honeys possessing H2O2 concentrations lower than 2.5 mM were still active in this process. Secondly, DNA degradation by active honeys was abolished by removal of H2O2 by catalase. Thirdly, honeys with the low content of H2O2 were unable to degrade DNA but the supplementation with 2 mM of hydrogen peroxide caused the appearance of this activity. The extent of DNA degradation by honey, which was supplemented with H2O2, was comparable to that of active honeys.

Heat-treatment of active honeys prior to incubation with E. coli cultures did not prevent DNA degradation, suggesting against the involvement of DNase in this process. Moreover, not all tested honeys displayed DNA degrading activity on E. coli cells. Given that bacterial cells are impermeable to DNase, the DNA degradation by honeys observed in this study could not be simply explained by the DNase contaminations. Rather, the close relationship between DNA degradation and H2O2 content in honeys advocates for the role of H2O2 in the mechanism of DNA cleavage.

DNA degradation is a lethal event which ultimately kills the cell. Literature data indicate that the concentration of hydrogen peroxide plays a decisive role in the type of cell death that follows H2O2 exposure. In simplified in vitro models, where direct effects of hydrogen peroxide on bacterial cells were analyzed, two separate modes of killing were observed for E. coli. At low concentrations of H2O2 (≤2.5 mM), E. coli cells were dying because of DNA damage inflicted on the metabolically active cells (Imlay and Linn, 1986; Imlay and Linn, 1987a,b; Brandi et al., 1989). At H2O2 concentrations of 10–50 mM, cell death resulted from cytotoxic effects due to hydroxyl radicals formed from hydrogen peroxide (Imlay and Linn, 1987a,b; Brandi et al., 1989). In a full agreement with these data, we established that the minimum DNA degrading activity of exogenous H2O2 on E. coli cells was 2.5 mM (2.5 μmoles/107cfu/ml). In contrast to exogenous H2O2, the minimum DNA degrading activity of honey H2O2 was below 2.5 mM. The lower concentrations of honeys H2O2 required to effectively degrade chromosomal DNA strongly suggest that the oxidizing effect of H2O2 was augmented by other honey components such as transition metals (Fe, Cu) commonly present in honeys. In support of this notion, the recent literature evidence indicates that it is the hydroxyl radical (HO) that is produced in the metal-catalyzed Fenton reaction from H2O2 rather than molecular hydrogen peroxide that causes the oxidative damage to membrane structures, proteins, and DNA (Imlay et al., 1988; Storz and Imlay, 1999; Cabiscol et al., 2000; Imlay, 2003).

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that honey H2O2 exerted bacteriostatic and DNA degrading activities to bacterial cells. The extent of damaging effects of honey H2O2 was strongly influenced by the bacterial sensitivity to oxidative stress, the growth phase and their survival strategy (non-spore forming versus spore forming species) as well as by the modulation of other honey compounds.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds from the Agricultural Adaptation Council, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (ADV-380), and the Ontario Centres of Excellence (BM50849) awarded to Katrina Brudzynski.

References

- Alaux C., Ducloz F., Crauser D., Le Conte Y. (2010). Diet effects on honeybee immunocompetence. Biol. Lett. 6, 562–565 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen K. L., Molan P. C., Reid G. M. (1991). A survey of the antibacterial activity of some New Zealand honeys. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 43, 817–822 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1991.tb03186.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai H., Konat G. W. (2003). Hydrogen peroxide mediates higher order chromatin degradation. Neurochem. Int. 42, 123–129 10.1016/S0197-0186(02)00072-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandi G., Cattabeni F., Albano A., Cantoni O. (1989). Role of hydroxyl radicals in Escherichia coli killing induced by hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 6, 47–55 10.3109/10715768909073427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudzynski K. (2006). Effect of hydrogen peroxide on antibacterial activities of Canadian honeys. Can. J. Microbiol. 52, 1228–1237 10.1139/w06-086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudzynski K., Miotto D. (2011a). The recognition of high molecular weight melanoidins as the main components responsible for radical-scavenging capacity of unheated and heat-treated Canadian honeys. Food Chem. 125, 570–575 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.09.049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brudzynski K., Miotto D. (2011b). Honey melanoidins. Analysis of a composition of the high molecular weight melanoidin fractions exhibiting radical scavenging capacity. Food Chem. 127, 1023–1030 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.01.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bsat N., Herbig A., Casillas-Martinez L., Setlow P., Helmann J. D. (1998). Bacillus subtilis contains multiple Fur homologues: identification of the iron uptake (Fur) and peroxide regulon (PerR) repressors. Mol. Microbiol. 29, 189–198 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00921.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabiscol E., Tamarit J., Ros J. (2000). Oxidative stress in bacteria and protein damage by reactive oxygen species. Int. Microbiol. 3, 3–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Schellhorn H. E. (2003).Controlled induction of the RpoS regulon in Escherichia coli. Can. J. Microbiol. 44, 707–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. L., Keramati I., Helmann J. D. (1995). Coordinate regulation of Bacillus subtilis peroxide stress genes by hydrogen peroxide and metal ions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 8190–8194 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christman M. F., Storz G., Ames B. N. (1989). OxyR, a positive regulator of hydrogen peroxide-inducible genes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, is homologous to a family of bacterial regulatory proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 3484–3488 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K. J. A. (1999). The broad spectrum of responses to oxidant in proliferating cells: a new paradigm for oxidative stress. IUBMB Life 48, 41–47 10.1080/713803463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K. J. A. (2000). Oxidative stress, antioxidant defences, and damage, removal, repair and replacement systems. IUBMB Life 50, 279–289 10.1080/15216540051081010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowds B. C. (1994). The oxidative stress response in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol. 124, 155–264 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07294.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowds B. C., Murphy P., McConnell D. J., Devine K. M. (1987). Relationship among oxidative stress, growth cycle, and sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 168, 5771–5775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan M., Linley E., Denyer S. P., McDonnell G., Simon C., Maillard J.-Y. (2010). Mode of action of hydrogen peroxide and other oxidizing agents: differences between liquid and gas forms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65, 2108–2115 10.1093/jac/dkq308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan H. M., Fridovich I. (1978). Regulation of the synthesis of catalase and peroxidase in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 6445–6420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay J. A. (2003). Pathways of oxidative damage. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57, 395–418 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay J. A., Chin S. M., Linn S. (1988). Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science 240, 640–642 10.1126/science.2834821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay J. A., Linn S. (1986). Bimodal pattern of killing of DNA-repair defective or anoxically grown Escherichia coli by hydrogen peroxide. Bacteriology 166, 519–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay J. A., Linn S. (1987a). Mutagenesis and stress response induced in Escherichia coli by hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 169, 2967–2976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay J. A., Linn S. (1987b). DNA damage and oxygen radical toxicity. Science 240, 1302–1309 10.1126/science.3287616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish J. S., Blair S., Carter D. A. (2011). The antibacterial activity of honey derived from Australian flora. PLoS ONE 6, e18229. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen P. C., Hu B., Strutinsky J., Sparling R. (1998). Regulation in the rpoS regulon of Escherichia coli. Can. J. Microbiol. 44, 707–717 10.1139/w98-069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen P. C., Switala J. J. (1987). Multiple catalases in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 169, 3601–3607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molan P. C., Russell K. M. (1988). Non-peroxide antibacterial activity in some New Zealand honeys. J. Apic. Res. 27, 62–67 [Google Scholar]

- Pernal S. F., Currie R. W. (2000). Pollen quality of fresh and 1-year-old single pollen diets for worker honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). Apidologie 31, 387–409 10.1051/apido:2000130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro G. F., Côrte-Real M., Björn J. (2006). Characterization of DNA damage in yeast apoptosis induced by hydrogen peroxide, acetic acid, and hyperosmotic shock. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4584–4591 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutala W. A., Weber J. D., The Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (2008). Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Department of Health and Human Services USA; Chapel Hill, NC [Google Scholar]

- Seaver L. C., Imlay J. A. (2001). Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase is the primary scavenger of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183, 7173–7181 10.1128/JB.183.24.7173-7181.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz G., Imlay J. A. (1999). Oxidative stress. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2, 188–194 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80033-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz G., Tartaglia L. A., Ames B. N. (1990). Transcriptional regulator of oxidative stress-inducible genes: direct activation by oxidation. Science 248, 189–194 10.1126/science.2183352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston R. J. (2000). The contribution of catalase and other natural products to the antibacterial activity of honey: a review. Food Chem. 71, 235–239 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00162-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White J. H., Subers M. H., Schepartz A. I. (1963). The identification of inhibine, the antibacterial factor in honey, as hydrogen peroxide and its origin in a honey glucose-oxidase system. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 73, 57–70 10.1016/0926-6569(63)90108-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M., Doan B., Schneider T. D., Storz G. (1999). OxyR and SoxRS regulation of fur. J. Bacteriol. 181, 4639–4643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]