Abstract

Patient presenting as a case of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (TLE) are usually resistant to antiepileptic drugs and surgery is the treatment of choice. This type of epilepsy may be due to Mesial Temporal Sclerosis (MTS), tumors [i.e. low grade glioma, Arterio-Venous Malformation (AVM) etc], trauma, infection (Tuberculosis) etc. Here we report five cases of surgically treated TLE that were due to a MTS, MTS with arachnoid cyst, low grade ganglioglioma, high grade ganglioglioma and a tuberculoma in the department of neurosurgery, Dhaka Medical College Hospital and Islami Bank Central Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh from August 2009 to February 2010. In all cases the only presenting symptoms was complex partial seizures (psychomotor epilepsy) for which all underwent scalp EEG (Electro Encephalogram) and MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) of Brain. All patients were managed by amygdalohippocampectomy plus standard anterior lobectomy. One patient with high grade ganglioglioma recurred within two months of operation and expired within five months. The rest of the cases are seizure and disease free till the last follow up.

Keywords: Temporal lobe epilepsy, Microneurosurgical management, Anterior temporal lobectomy, Amygdalohippocampectomy

Introduction

About 20% epilepsies are drug resistant and intractable11. In this group of patients some form of surgery is usually needed either to cure epilepsy or to improve living standard by better control of epilepsy with drugs. The idea of surgical treatment for epilepsy is not new. However, widespread use and general acceptance of this treatment has only been achieved during the past three decades. Improvements in imaging resulted in an increased ability for preoperative identification of intracerebral and potentially epileptogenic lesions. High resolution magnetic resonance imaging plays a major role in structural imaging. EEG (especially video EEG), MRI and other functional imaging usually help in identification of epileptogenic zone or foci. Today, epilepsy surgery is more effective and conveys a better seizure control rate. It has become safer and less invasive, with lower morbidity and mortality rates.22

Here we report our initial experience of intractable temporal lobe epilepsy surgery (amygdalohippocampectomy) with divergent medial temporal lobe pathologies in Bangladesh where epilepsy surgery has just started with limited resources.

Pre operative workup

Patients with intractable TLE were referred from our neurology side and we went for complete history, clinical examination, high resolution MRI of brain(1.5 Tesla unit, 5 mm axial FLAIR , 5 mm coronal FLAIR images along other routine images were taken), interictal scalp EEG and neuropsychological evaluation for intelligence, attention, visual and verbal memory, language, and higher verbal and visual reasoning routinely. Only those patients with a definite temporal lobe lesion/s on MRI along with concordant interictal epileptiform discharge from the same temporal side were taken up for surgery. Wada test was not done in any case. Facilities for Video EEG, PET, SPECT, neuronavigation were not available.

Surgical resection

These cases were our initiation of epilepsy surgery and possibly foundation for development of full blown epilepsy surgery in Bangladesh. Though there might be alternative surgical options, in all five cases we went for amygdalohippocampectomy plus standard ATL with or without lesionectomy.

Case presentation

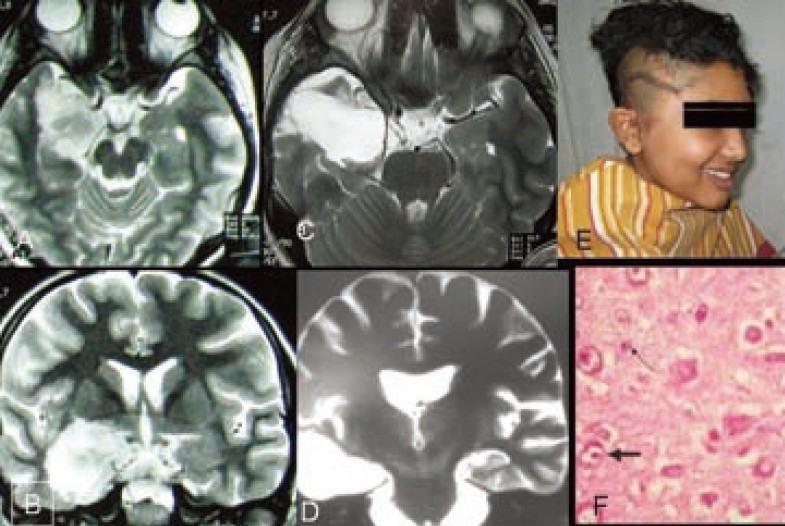

Case 1 (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

MRI of brain T2 weighted images. A-axial &B-coronal showing right amygdalohippocampal tumor. C&D-MRI T2 weighted images after amygdalohippocampectomy and standard anterior temporal lobectomy. E- Patient after operation showing operation site. F-Histopathology (Microphotograph of ganglioglioma)

A 11 year old right handed high school girl presented with sudden development of uneasiness, perception of smell of kerosene, followed by loss of awareness of surroundings for a period of 1-2 minutes for last 20 months. Initially the episode of seizure were around 3-4 attacks per week but later it increased to 10-12 attacks a day. She had no significant past events related to present disease. There was no significant event in her birth process and family history was negative for such type of disease. She had no complaints suggestive of intracranial space occupying lesion or raised intracranial pressure. Complete physical and neurological examination including higher mental functions revealed no abnormality. Scalp EEG recording showed epileptic spikes originating from left centro-temporal region. MRI of brain showed features of left amygdalo-hippocampal mass lesion (1×1.5×1cm) suggestive of low grade glioma. She was on two anti epileptic drugs (AED) [Carbamazipine and sodium valproate] for the last 16 months but seizure frequency did not reduce rather it increased further.

She underwent amygdalohippocampectomy with lesionectomy plus standard anterior temporal lobectomy. Histopathology revealed grade-1 ganglioglioma. Postoperatively she recovered uneventfully. She was put on carbamazipine 100mg tablet thrice daily that was tapered and stopped 4 months after operation. She has been seizure free for last seven months. Post operative MRI of brain at the end of 4 months after operation showed no residual or recurrent tumor and there was no visual field defect or nominal aphasia.

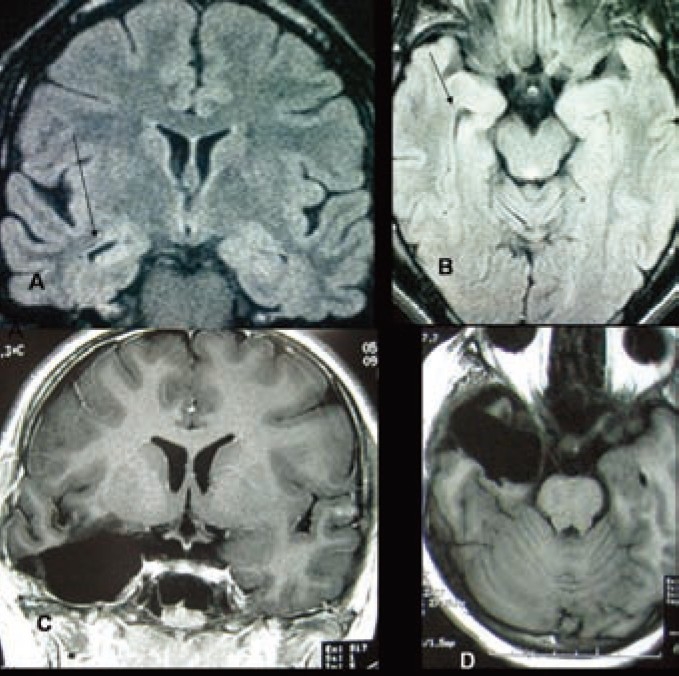

Case 2 (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

A-MRI of brain (FLAIR) coronal image and B-Axial mage showing right mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS) with compensatory dilatation of temporal horn in comparison to left temporal horn. C&D-MRI of brain T1 weighted images coronal and axial view respectively after amygdalohippocampectomy and standard anterior temporal lobectomy.

A 13 years old girl presented with sudden staring followed by unconsciousness and tonic-clonic convulsions involving left upper and lower limbs since birth. All these events persisted for only 40-50sec.She had history of mild birth asphyxia. Her family history for such kind of illness was negative. Her parents visited several physicians both in the country and abroad. She took several AEDs in combination for several years without significant improvement in seizure control. There were 25-30 seizure attacks per day even with multiple AEDs (Carbamazepine + Phenobarbitone + Valproic acid).Scalp EEG revealed abnormal epileptic spikes originating from right centro-temporal region. MRI of brain showed features suggestive of right mesial temporal sclerosis.

She underwent right amygdalohippocampectomy plus standard anterior temporal lobectomy. Postoperatively she recovered uneventfully. She was put on carbamazipine 100mg tablet thrice daily that was tapered 4 months after operation. She is seizure free for last six months while on carbamazipine 100mg 12 hourly.

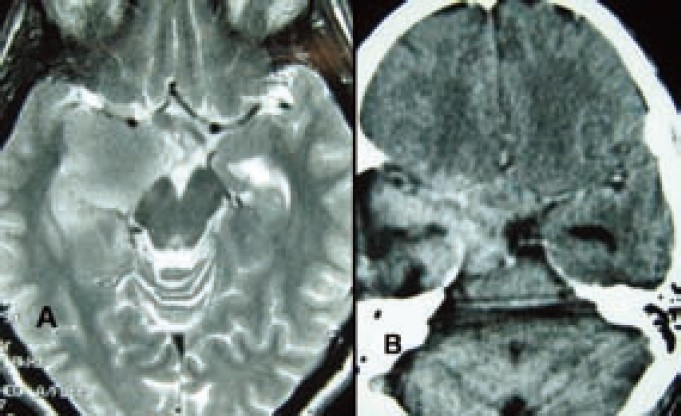

Case 3 (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

A-Preoperative MRI of brain T2 weighted axial image showing right amygdala growth suggestive of glioma. B-Immadiate post operative CT scan of brain axial view showing haematoma in right temporal region that caused temporary hemiplegia. (4 months after the surgery, the patient succumbed to a recurrent Grade-III ganglioglioma)

A forty one years old right handed cultivator presented with history of sudden onset uneasiness followed by smell of rotten meat for a period of 10-15 sec for last 2 months with 3-5 episodes of such events per day. The neurological examination including higher mental functions was normal except left sided extensor plantar and positive Hoffman signs. Scalp EEG recording showed epileptic spikes originating from right centro-temporal region. MRI of brain showed features of left amygdala mass lesion (2×1.5×1cm) suggestive of glioma that was compressing right cerebral peduncle. He underwent amygdalohippocampectomy with lesionectomy plus standard anterior temporal lobectomy. Histopathology revealed grade-3 (anaplastic) ganglioglioma. Postoperatively he developed left sided hemiparesis that recovered within seven days. He was put on carbamazipine 100mg tablet thrice daily and was advised radiotherapy but patient's relatives refused it. He was seizure free for 02 months but after that the seizure episodes returned along with left sided weakness and features of raised intracranial pressure. Follow up CT scan of brain at the end of 4 months showed huge recurrence of tumor. The patient expired five months after operation.

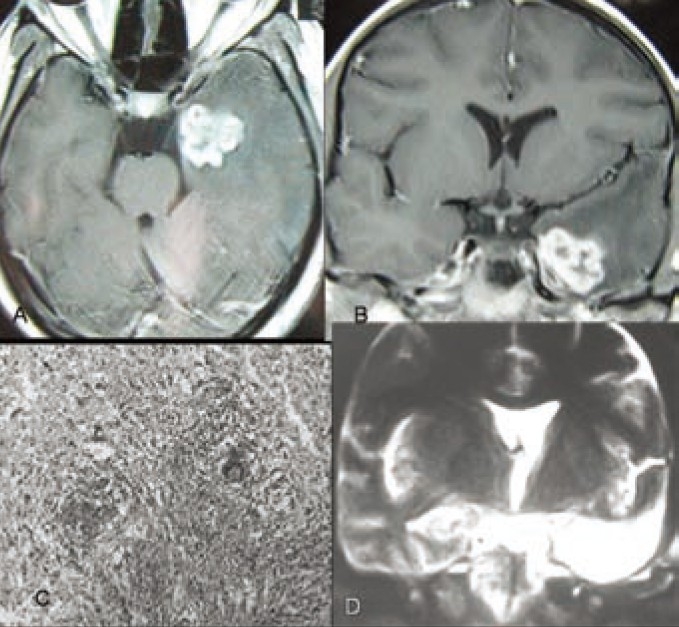

Case 4 (Figure 4):

Figure 4.

MRI of brain T1 weighted images A-axial view and B-coronal view showing hyperintense left anterior medial temporal lobe lesion causing TLE, C- Histopathology (Microphotograph showing tuberculosis), D-MRI of brain T2 weighted coronal image after left sided amygdalohippocampectomy and standard anterior temporal lobectomy.

Patient KS (26 years old, right handed house wife) presented with epigastric discomfort with feeling of hunger followed by loss of awareness of surroundings with lip smacking for a period 90-120 sec for last 5 months. Initially these events were less frequent (1-2 attacks/week).She was taking AEDs (Carbamazipine+Phenytoin) for last 4 months. But recently frequency of seizures increased to 4-5 attacks/day. Her general, systemic and neurological examination including higher mental functions was normal. Scalp EEG showed epileptogenic focus in left temporal region. MRI of brain showed left antero-inferio-medial temporal hyperintense lesion of 2×2×1.5 cm mass effacing left temporal horn. She underwent amygdalohippocampectomy with lesionectomy plus standard anterior temporal lobectomy. Histopathology revealed tuberculosis. Postoperatively she recovered uneventfully and anti-tubercular therapy was started. She was put on carbamazepine 100mg tablet thrice daily, which was tapered and stopped 4 months after operation. She is seizure free for last five months. Post operative MRI of brain at the end of 4 months showed no residual or recurrent lesion and there was no visual field defect or nominal aphasia.

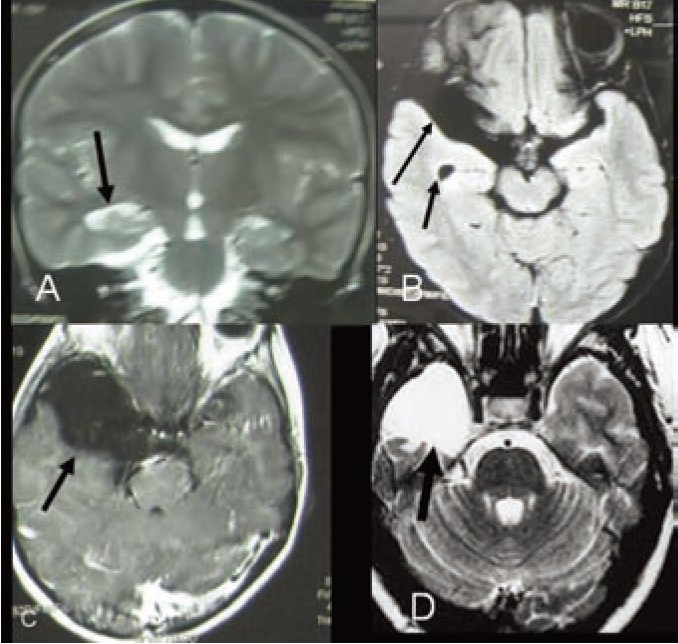

Case 5 (Figure 5):

Figure 5.

MRI of brain A- Coronal image (FLAIR) showing right mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS) with compensatory dilatation of temporal horn in comparison to left temporal horn with anterior temporal arachnoid cyst and right temporal hypoplasia. B- Axial image (T2W) showing right mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS).C- Axial T1W image showing large right anterior temporal arachnoid cyst. D-Postoperative MRI of brain with T2 weighted axial image after amygdalohippocampectomy with excision of arachnoid cyst and standard anterior temporal lobectomy.

A 12 years old boy presented with sudden transient global headache, nausea followed by unconsciousness for 1-2 minutes. He regained consciousness but was unaware of time, place and person for another 3-5 minutes. He was suffering from this event repeatedly for last five years. Initially there were 12-15 attacks per year that increased to 3-5 attacks per day even while he was on adequate AEDs treatment (Carbamazipine+Sodium Valproate). His family history was negative for such kind of illnesses and his birth history was normal. Scalp EEG revealed abnormal epileptic spikes originating from right posterior centro-temporal region along with right anterior temporal slowing. MRI of brain showed features of right mesial temporal sclerosis (Right temporal horn apparent dilatation, decreased hippocampal volume and punctuate hyperintensity in hippocampus) and right temporal lobe hypoplasia along with large anterior temporal arachnoid cyst (4x4x5cm) without mass effect.

He underwent right amygdalohippocampectomy plus standard anterior temporal lobectomy with excision of arachnoid cyst. Postoperatively, he recovered uneventfully. He was put on carbamazepine 100mg tablet thrice daily after operation. He is seizure free for last three month with carbamazepine. He has no clinical or perimetric visual field defect.

Discussion

William MacEwen (1848–1924) and Victor Horsley (1857–1916) in London were the first to localize and remove epileptogenic lesions, as identified by their symptomatogenic zone, according to the pioneering work of John Hughlings Jackson (1835–1911)22. After a long dormant stage, epilepsy surgery developed tremendously in last three decades22. Among the drug resistant intractable epilepsy, temporal lobe epilepsy is the commonest (about 80%) and it responds beautifully to surgery11,22. Like obstructive jaundice (which is called surgical jaundice) temporal lobe epilepsy is called the surgical epilepsy. Common causes of intractable surgical epilepsy are cortical dysplasia, MTS, Temporal lobe and other lobe tumors [DNET (Dysembryoplastic Neuroepithelial Tumor), ganglioglioma and others],cortical atrophy, stroke, trauma, vascular lesions (arterio-venous malformations, cavernoma )etc11,12,22.

In case 1 the patient was suffering from intractable TLE. Imaging confirmed a epileptogenic lesion in the amygdala and hippocampal area which was a low grade ganglioglioma. Low grade ganglioglioma is one of the common benign lesions in this area causing TLE especially in children for which surgery is needed12. Appropriate surgical intervention is usually curative.

In case 2 intractable TLE is due to MTS. This girl has history of birth asphyxia, so we can think this MTS was due to birth asphyxia which is a common cause of MTS. In case-5 intractable epilepsy was due to MTS with temporal lobe hypoplasia rather than arachnoid cyst. Epilepsy associated with MTS is usually AED resistant and needs surgery. Result of surgery in these cases is excellent. In these cases combination of AEDs with adequate dosage failed to control disabling epilepsy. In most of the cases surgery is curative if there is no other focus or at least good control of epilepsy can be achieved with AED12,22.

Case 3 had an anaplastic ganglioglioma in amygdala and hippocampus as a less common cause of TLE. Surgical treatment confirms histopathology along with palliation of symptoms. Radiotherapy improves the outcome only a little. Symptoms recur along with other features suggestive of rapidly growing mass in intracranial space which is usually fatal.

In case 4, TLE was due to a large tuberculoma in medial temporal lobe. Though tuberculosis is common in this subcontinent but tuberculosis in such a situation causing TLE without the evidence of tuberculosis elsewhere in the body and without clinical features of tuberculosis is not common. Preoperatively her seizure attack was intractable. Preoperative imaging was suggestive of meningioma or ependymoma rather than tuberculosis. Peroperatively the tumor was attached with tentorium cerebelli that instigated us to believe that it was a meningioma, though consistency of the lesion was variable and peculiar. Postoperative histopathology report was astounding for us but blissful for the patient. Though neurocystocercosis, schistosomiasis in temporal lobe may cause TLE but onlyt tuberculoma causing TLE is very rare in literature.

The question of how to resect an epileptogenic focus or lesion in order to achieve seizure control is still a matter of discussion. Though in the last decade there is a tendency for smaller resections (Selective AH, Polar resection with AH, Temporal basal resection plus AH, anterior AH, lesionectomy, lesionectomy plus AH etc) in TLE . Residual tissue is a well known factor for seizure recurrence, and is, as a result of limited exposure, thought to be somewhat more frequent after AH compared with ATL. Reoperation for residual tissue removal should be considered in these patients, with additional success rates of approximately 50% for abolishing seizures.22

Anterior temporal lobectomy is the most widely performed standard resection for TLE, and most of the desired results have been obtained with this procedure. Nevertheless, beneficial effects—especially regarding postoperative neuropsychological results—have been described for more limited temporal resections: preservation of healthy and nonepileptogenic brain tissue may improve postoperative function. Similar rates of seizure relief and side effects were obtained with ATL and AH for the treatment of TLE.7,22

We went for amygdalohippocampectomy with or without lesionectomy plus standard anterior temporal lobectomy in all cases but other form of smaller resections including selective amygdalohippocampectomy with lesionectomy could be alternative surgical options to these lesions22. Size of the lesion, possibility of different pathology, narrow space through trans-sylvian route and possibility of manipulation and damage to critical vessels and neural structures and most importantly less familiarity of the approach along with less success rate of selective amygdalohippocampectomy in controlling epilepsy helped us to take decision in favor of trans middle temporal gyrus approach amygdalohippocampectomy with lesionectomy plus standard anterior temporal lobectomy instead of selective amygdalohippocampectomy in the hope to cure epilepsy as well as the lesion. It has been suggested that the amount of tissue resected in mesiotemporal operations is crucial for the surgical success in mesial TLE1,5,18,20,27.

In a randomized, prospective study comparing the trans-sylvian with the transcortical approach, seizure outcome was similar14,21. Middle temporal gyrus approach does not usually damage the optic radiation (Meyer loop) unless excessive backward and upward retraction or misdirection of transcortical incision is done6. In all of our cases we found no visual field defect both clinically and in perimetry.

Generally, complication rates of epilepsy surgery are relatively low and thought to be acceptable, with approximately 1 to 2% associated permanent morbidity.2 The rate of minor complications was 3.6%, and the rate of major complications was 1.26% in the Zürich series of 478 amygdalohippocampectomies. Persisting hemiparesis occurred in 0.84% patients as a result of choroidal infarcts of the internal capsule26. Typical neurological complications after surgery for TLE include temporary dysphasia or hemiparesis as caused by manipulation-induced brain swelling or brain contusion, small vessel infarction, and hemorrhage. There are the classic surgical problems such as infection, thrombosis, etc., in the range of 2 to 4%, which rarely cause permanent damage.2 The mortality rate is clearly below 1% in most series. In our case 3 post operatively patient developed transient hemiparesis that was due to haematoma in the operative field compressing one of the crus cerebri.

Seizure control rate in MTS after surgery is excellent12,22. Certain developmental tumors, e.g., gangliogliomas and dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors, can be treated with excellent seizure-control rates in most of the patients19. Also, certain types of low-grade gliomas (e.g., isomorphic subtype of low-grade astrocytoma, pilocytic astrocytoma) can be operated on with excellent results3,9,15,17,25. In a series limited to preoperatively tailored resections for lesional (nonsclerotic) mesial TLE, satisfactory seizure control was obtained in 86% of patients.7 Outcome with lesionectomy and corticectomy was excellent, especially when a tumor was present (95% satisfactory seizure control)23. Although it depends more on patient selection than surgery, it should be noted that operating on children and adolescents with epilepsy is extraordinarily promising with respect to seizure control and neuropsychological and psychosocial outcomes4,8,10,11,16,25. ‘Engel grading’ is used for assessment of outcome of epilepsy surgery. In view of epilepsy control in our series, final comment can not be made as follow up period is still small but in this small follow up period control of seizure has remained excellent.

Conclusion

Epilepsy surgery today is more effective with better seizure control rates; it is safer and less invasive with lower morbidity and mortality rates. For successful development and upgradation of epilepsy surgery program, a team of epileptologist, neuropathologist, neurophysiologist, neuroradiologist and neurosurgeon with the facilities of video EEG, MRI and other imaging facilities is very essential. Finally it should be realized that an expert epilepsy neurosurgeon is helpless without an able epileptologist who will at first get hold of the patients and participate in the management of all epilepsies including “surgical epilepsy”.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express the deep appreciation to Prof. Dr. Atul Goel who gave training and inspiration for starting epilepsy surgery in Bangladesh in his Microneurosurgical fellowship Course at King Edward Hospital, Parel, Mumbai, India.

References

- 1.Awad IA, Katz A, Hahn JF, Kong AK, Ahl J, Lüders H. Extent of resection in temporal lobectomy for epilepsy. I. Interobserver analysis and correlation with seizure outcome. Epilepsia. 1989;30:756–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrens E, Schramm J, Zentner J, König R. Surgical and neurological complications in a series of 708 epilepsy surgery procedures. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:1–10. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199707000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blümcke I, Luyken C, Urbach H, Schramm J, Wiestler OD. An isomorphic subtype of long-term epilepsy-associated astrocytomas associated with benign prognosis. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2004;107:381–388. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0833-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blume WT. Temporal lobe epilepsy surgery in childhood: Rationale for greater use. Can J Neurol Sci. 1997;24:95–98. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100021399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonilha L, Kobayashi E, Mattos JP, Honorato DC, Li LM, Cendes F. Value of extent of hippocampal resection in the surgical treatment of temporal lobe epilepsy. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62:15–20. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2004000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chowdhury FH, Khan AH. Anterior and lateral extension of optic radiation and safety of amygdalohippocampectomy through middle temporal gyrus: A cadaveric study of 11 cerebral hemispheres. Asian Journal of Neurosurgery. 2010;4:78–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clusmann H, Kral T, Fackeldey E, Blümcke I, Helmstaedter C, von Oertzen J, Urbach H, Schramm J. Lesional mesial temporal lobe epilepsy and limited resections: Prognostic factors and outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1589–1596. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.024208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clusmann H, Kral T, Gleissner U, Sassen R, Urbach H, Blümcke I, Bogucki J, Schramm J. Analysis of different types of resection for pediatric patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:847–859. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000114141.37640.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daumas-Duport C, Scheithauer BW, Chodkiewicz JP, Laws ER, Vedrenne C. Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor: A surgically curable tumor of young patients with intractable partial seizures. Report of thirty-nine cases. Neurosurgery. 1988;23:545–556. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198811000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gleissner U, Sassen R, Lendt M, Clusmann H, Elger CE, Helmstaedter C. Pre- and postoperative verbal memory in pediatric patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2002;51:287–296. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(02)00158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg MS., MD . Seizures. In: Greenberg MS MD, editor. Hand book of Neurosurgery. 5th ed. Newyork: Thieme; 2001. pp. 254–284. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey S, Cross JH, Shinnar S, Matheren BW. The ILAE Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery Survey Taskforce. Defining the spectrum of international practice in pediatric epilepsy surgery patients. Epilepsia. 2008;49(1):146–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kral T, Kuczaty S, Blümcke I, Urbach H, Clusmann H, Wiestler OD, Elger C, Schramm J. Postsurgical outcome of children and adolescents with medically refractory frontal lobe epilepsies. Childs Nerv Syst. 2001;17:595–601. doi: 10.1007/s003810100497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lutz MT, Clusmann H, Elger CE, Schramm J, Helmstaedter C. Neuropsychological outcome after selective amygdalohippocampectomy with transsylvian versus transcortical approach: A randomized prospective clinical trial of surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2004;45:809–816. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.54003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luyken C, Blümcke I, Fimmers R, Urbach H, Elger CE, Wiestler OD, Schramm J. The spectrum of long-term epilepsy-associated tumors: Longterm seizure and tumor outcome and neurosurgical aspects. Epilepsia. 2003;44:822–830. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.56102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathern GW, Giza CC, Yudovin S, Vinters HV, Peacock WJ, Shewmon DA, Shields WD. Postoperative seizure control and antiepileptic drug use in pediatric epilepsy surgery patients: The UCLA experience, 1986–1997. Epilepsia. 1999;40:1740–1749. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris HH, Matkovic Z, Estes ML, Prayson RA, Comair YG, Turnbull J, Najm I, Kotagal P, Wyllie E. Ganglioglioma and intractable epilepsy: Clinical and neurophysiologic features and predictors of outcome after surgery. Epilepsia. 1998;39:307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nayel MH, Awad IA, Luders H. Extent of mesiobasal resection determines outcome after temporal lobectomy for intractable complex partial seizures. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:55–61. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199107000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pilcher WH, Silbergeld DL, Berger MS, Ojemann GA. Intraoperative electrocorticography during tumor resection: Impact on seizure outcome in patients with gangliogliomas. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:891–902. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.6.0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renowden SA, Matkovic Z, Adams CB, Carpenter K, Oxbury S, Molyneux AJ, Anslow P, Oxbury J. Selective amygdalohippocampectomy for hippocampal sclerosis: Postoperative MR appearance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1855–1861. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaller C, Jung A, Clusmann H, Schramm J, Meyer B. Rate of vasospasm following the transsylvian versus transcortical approach for selective amygdalohippocampectomy. Neurol Res. 2004;26:666–670. doi: 10.1179/016164104225015921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schramm J, MD, Clusmann H., MD Surgery of epilepsy. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(SHC Suppl 2):463–481. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000316250.69898.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schramm J, Kral T, Grunwald T, Blümcke I. Surgical treatment for neocortical temporal lobe epilepsy: Clinical and surgical aspects and seizure outcome. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:33–42. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.94.1.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schramm J, Kral T, Kurthen M, Blümcke I. Surgery to treat focal frontal lobe epilepsy in adults. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:644–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westerveld M, Sass KJ, Chelune GJ, Hermann BP, Barr WB, Loring DW, Strauss E, Trenerry MR, Perrine K, Spencer DD. Temporal lobectomy in children: Cognitive outcome. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:24–30. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.1.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wieser HG. Selective amygdalohippocampectomy has major advantages. In: Miller JW, Silbergeld DL, editors. Epilepsy Surgery: Principles and Controversies. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2006. pp. 465–478. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyler AR, Hermann BP, Somes G. Extent of medial temporal resection on outcome from anterior temporal lobectomy: A randomized prospective study. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:982–991. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199511000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]