Abstract

This report concerns a 12-year-old male with intractable seizures over a long period. The case fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for nonherpetic acute limbic encephalitis. He had frequent convulsions starting with a partial seizure at the left angle of the mouth and progressing to secondary generalized seizures. He was treated with several anticonvulsants, combined with methylprednisolone and γ-globulin under mechanical ventilation. However, his convulsions reappeared after tapering of the barbiturate. His magnetic resonance imaging showed a high intensity area in the hippocampus by FLAIR and diffusion. After five months he recovered without serious sequelae. Virological studies, including for herpes simplex virus, were all negative. He was transiently positive for antiglutamate receptor antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid and serum.

Keywords: acute limbic encephalitis, antiglutamate receptor, interleukin-6, child, intractable seizures

Introduction

Nonherpetic acute limbic encephalitis (NHALE), reported as a novel type of acute limbic encephalitis in young women where herpes simplex is not detected, has attracted attention recently.1 The cause of this disease is not identified, but a connection with the glutamate receptor antibody has been reported. However, there are few reports of children with NHALE and antiglutamate receptor antibodies. We report a rare case of a 12-year-old-boy with NHALE who was transiently positive for antiglutamate receptor antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid and serum. This is the first report to show the time course of glutamate receptor changes in children with a diagnosis of NHALE.

Case Report

A 12-year-old boy was admitted with convulsions to the Department of Pediatrics at Tokyo Medical University Hospital. He was born as appropriate-for-dates by caesarean section because of fetal distress. His body weight was 3403 g at 41 weeks. His past medical history and family history were unremarkable. He had one episode of febrile convulsions at the age of one year, but otherwise developed normally without any serious illness. He had a high fever for two days before the episode on July 10, 2004, which came down, but he had generalized tonic-clonic seizures lasting for five minutes and was admitted to hospital.

On admission, his body temperature was 36.7°C, and he was in a stupor (20–30 on the Japan Coma Scale). He showed a clustering of seizures with automatic oral movements and unconsciousness and had ongoing short-term memory problems. His interictal electroencephalogram, brain magnetic resonance imaging, and cerebrospinal fluid parameters were all normal. He was diagnosed to have encephalopathy, and was treated with anticonvulsants, pulsed steroid therapy (three days of methylprednisolone 30 mg/kg), and acyclovir.

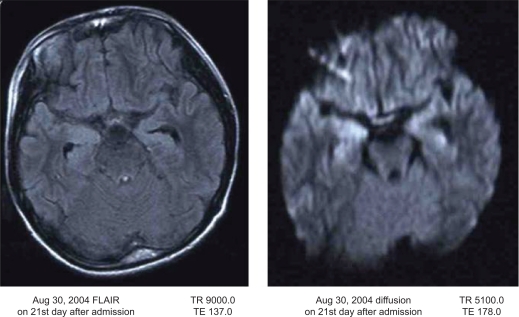

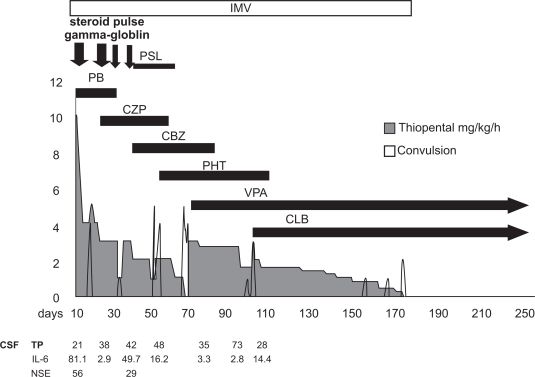

Because his convulsions were intractable, he was moved to our department 10 days after the onset of the illness in order to achieve seizure control. On arrival, his Japan Coma Scale was 100–200. His light reflex was prompt, and the deep reflex was decreased. White blood cell levels were 14,900/μL and hemoglobin was 14.1 g/dL. C-reactive protein was high at 2.6 mg/dL. Creatine phosphokinase was 547 U/L. IgG, IgA, and IgM were 1784 mg/dL, 168 mg/dL, and 217 mg/dL, respectively. Serum interleukin-6 and soluble interleukin-2 receptor were increased to 38.5 pg/mL (normal 6 pg/mL) and 815 U/mL (normal 500 U/mL), respectively. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed elevated interleukin-6 at 81.1 pg/mL (normal 6 pg/mL) and neuron-specific enolase at 56 ng/mL (normal 16.3 ng/mL). Viral studies, including polymerase chain reaction for enterovirus, herpes simplex virus, and human herpesvirus-6, were all negative. Cell count, protein, and CSF pressure were all normal. Metabolic studies (amino acid, muscle biopsy, fatty acid, lactic acid, pyruvic acid) were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a high density area in the hippocampus by FLAIR and diffusion on day 21 (Fig. 1). Because he had clustered convulsions, comprising partial seizures starting at the left angle of the mouth with unconsciousness and generalized seizures, he was treated under mechanical ventilation. Depressants for cerebrospinal pressure and anticonvulsants (barbiturate, phenobarbital, midazolam, clonazepam, carbamazepine, phenytoin) were used. A combination of pulsed methylprednisolone therapy for three days and high-dose γ-globulin was also used. Despite this therapy, his convulsions reappeared after tapering the barbiturates over five months. On day 173 after admission, his convulsions were finally controlled with clonazepam and valproic acid, and discontinuation of mechanical ventilation and barbiturates was possible (Fig. 2). He showed mild gait disturbances because of contractures of the foot joints during his prolonged bed rest, but did not show any mental retardation (language 105, physical 89, total 97, on Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children III).

Figure 1.

MRI imaging on 21st day after the onset. Bilateral hippocampus show high intensity area (right dominant) was visible.

Figure 2.

The general cause (y axis mean numbers of seizure per day) of the patient.

The patient was discharged after 258 days. His brain images showed neither atrophy nor enlargement of the ventricles. For two years he had no convulsions. Antiglutamate receptor antibodies were detected transiently in serum and cerebrospinal fluid after one month, as shown in Table 1. Although cerebrospinal fluid findings suggested viral infection, a virological study could not demonstrate infection attributable to herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2, varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, measles virus, mumps virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, or influenza virus type A and B in serum.

Table 1.

Anti-glutamate receptor antibodies in the patient which were assayed by the method of Takahashi.2

| Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 30 | Day 77 | Day 98 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebrospinal fluid | IgG epsilon-2 | − | − | + | − | − |

| Delta-2 | − | − | − | − | − | |

| IgM epsilon-2 | − | − | + | + | − | |

| Delta-2 | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Serum | IgG epsilon-2 | Not done | Not done | − | − | − |

| Delta-2 | Not done | Not done | + | + | + | |

| IgM epsilon-2 | Not done | Not done | ||||

| Delta-2 | Not done | Not done | − | + | + |

Discussion

This patient showed memory disturbance, unconsciousness, and clustering of seizures with oral automatisms requiring administration of multiple anticonvulsant medications, high-dose γ-globulin, pulsed steroid therapy, and thiopental. He did not present with febrile episodes during the period of seizure-clustering, interictal electroencephalographic abnormalities throughout the clinical course, or intellectual impairment as sequelae. As such, his clinical symptoms and magnetic resonance images are consistent with NHALE. Glutamate receptor antibody was detected in blood and spinal fluid. It has been reported that this antibody is often positive in Rasmussen syndrome, acute encephalitis/encephalopathy,2 and acute encephalitis with refractory repetitive partial seizures (AERRPS).3–6

Rasmussen’s syndrome, which occurs in childhood, presents with intractable partial motor seizures and slowly progressive neurological deterioration, hemiplegia, and intellectual impairment. Pathological studies demonstrate that this syndrome involves one hemisphere of the brain.7 Therefore, the clinical symptoms of the present case are not consistent with any of those disorders. From many studies of this syndrome, the antibody to the glutamate receptor has been thought to be a possible mechanism in which the antibody might directly trigger seizures by over-stimulation of the glutamate receptor.

In our case, the symptomatic zone was suspected to be the hippocampus with secondary radiation to the opercular region. His initial symptoms were similar to those of postencephalitic epilepsy which affects these regions first, but these cases usually have easily controlled seizures in the acute phase. In contrast, the seizures continued for about 170 days in our patient, and he recovered without any serious sequelae. Therefore, the clinical symptoms do not support a diagnosis of postencephalitic epilepsy.

The most important disorder to be considered for a differential diagnosis is AERRPS. The diagnostic criteria6 include three mandatory items, ie, acute onset of seizures or impairment of consciousness without underlying neurological abnormalities, extraordinary frequent, refractory partial seizures, and continuous switchover to refractory epilepsy without a latent period, and supporting findings of an antecedent febrile illness, persistent fever during acute phase, mild cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis or upregulation of inflammatory markers, electroencephalographic abnormalities, nonspecific magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities, and profound neurologic sequelae. The present case did not meet the third criterion for AERRPS.

On the other hand, the symptoms and images were very similar to those of NHALE. Childhood NHALE has been reported recently,8,9 but remains rare. NHALE is regarded as a new subtype of limbic encephalitis. Asaoka et al investigated six patients with NHALE and compared them with cases of herpes simplex virus encephalitis. The NHALE patients demonstrated both acute limbic encephalitis and magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in the bilateral hippocampus and amygdala. However, interleukin-6 and IFN-γ levels in cerebrospinal fluid from the patients with NHALE were significantly lower than in that from patients with herpes simplex encephalitis. Asaoka et al argued that an immunological process in this type of NHALE could be a possible source, rather than a direct viral infection.10

Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor ɛ2 were also reported by Hayashi et al in adult cases of NHALE.1 In our patient, we detected IgM type autoantibodies to glutamate receptor δ2 and ɛ2 in both the cerebrospinal fluid and serum, and these antibodies normalized in the cerebrospinal fluid over the clinical course of the illness. Antiglutamate receptor ɛ antibody in cerebrospinal fluid is known to correlate with mental retardation and late appearance of epilepsy. Antiglutamate receptor antibodies are also known to be detected in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with chronic progressive epilepsia partialis continua of childhood, patients with Rasmussen’s encephalitis,11 and those with AERRPS. Moreover, it has been reported that encephalitis and encephalopathy without any deterioration may also show positive for these antibodies.11,12 Recently, novel clinical syndromes, such as NHALE and AERRPS, which are suggested to be based on autoimmune mechanism, have been recognized as distinct clinical entities. The present case was diagnosed as NHALE, but shares some characteristics with AERRPS. More studies on autoimmune etiology are necessary. This 12-year-old boy with nonherpetic acute limbic encephalitis and transiently positive for antiglutamate receptor antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid and serum recovered after five months without serious sequelae.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Author(s) have provided signed confirmations to the publisher of their compliance with all applicable legal and ethical obligations in respect to declaration of conflicts of interest, funding, authorship and contributorship, and compliance with ethical requirements in respect to treatment of human and animal test subjects. If this article contains identifiable human subject(s) author(s) were required to supply signed patient consent prior to publication. Author(s) have confirmed that the published article is unique and not under consideration nor published by any other publication and that they have consent to reproduce any copyrighted material. The peer reviewers declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hayashi Y, Matsuyama Z, Takahashi Y, et al. A case of non-herpetic acute encephalitis with autoantibodies for ionotropic glutamate receptor delta2 and epsilon2. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2005;45:657–62. Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi Y. Anti-GluRɛ antibodies in intractable epilepsy after CNS infection in children. J Jap Pediatr Society. 2002;106:1402–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saito Y, Maegaki Y, Okamoto R, et al. Acute encephalitis with refractory, repetitive partial seizures: Case reports of this unusual post-encephalitic epilepsy. Brain Dev. 2008;29:147–56. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shyu CS, Lee HF, Chi CS, Chen CH. Acute encephalitis with refractory, repetitive partial seizures. Brain Dev. 2008;30:356–61. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito H, Mori K, Toda Y, Sugimoto M, Takahashi Y, Kuroda Y. A case of acute encephalitis with refractory, repetitive partial seizures, presenting autoanti-body to glutamate receptor Gluɛ2R antibody. Brain Dev. 2005;27:531–4. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakuma H. Acute encephalitis with refractory, repetitive partial seizures. Brain Dev. 2009;31:510–4. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart Y, Anderman F. Rasmussen’s syndrome. In: Roger J, Bureau M, Dravet CH, Genton P, Tassinari CA, Wolf P, editors. Epileptic Syndrome in Infancy, Childhood and Adolescence. 4th ed. Montrouge, France: John Libbey Eurotext Ltd; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki K, Jimi T, Wakayama Y, Yamamoto T, Nakayama R. A case of nonherpetic acute encephalitis presenting high intensity lesion at unilateral temporal cortex on MR FLAIR image. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1999;39:750–6. Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshikawa H, Yamazaki S. A child with non-herpetic acute limbic encephalitis. No To Hattatsu. 2003;35:429–31. Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asaoka K, Shoji H, Nishizaka S, et al. Non-herpetic acute limbic encephalitis: Cerebrospinal fluid cytokines and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Intern Med. 2004;43:42–8. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumakura A, Miyajima T, Fujii T, Takahashi Y, Ito M. A patient with epilepsia partialis continua with anti-glutamate receptor epsilon 2 antibodies. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29:160–3. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(03)00151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi Y, Mori H, Mishina M, et al. Autoantibodies to NMDA receptor in patients with chronic forms of epilepsia partialis continua. Neurology. 2003;61:891–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000086819.53078.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]