Abstract

Lung carcinogenesis in humans involves an accumulation of genetic and epigenetic changes that lead to alterations in normal lung epithelium, to in situ carcinoma, and finally to invasive and metastatic cancers. The loss of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-induced tumor suppressor function in tumors plays a pivotal role in this process, and our previous studies have shown that resistance to TGF-β in lung cancers occurs mostly through the loss of TGF-β type II receptor expression (TβRII). However, little is known about the mechanism of down-regulation of TβRII and how histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (HDIs) can restore TGF-β-induced tumor suppressor function. Here we show that HDIs restore TβRII expression and that DNA hypermethylation has no effect on TβRII promoter activity in lung cancer cell lines. TGF-β-induced tumor suppressor function is restored by HDIs in lung cancer cell lines that lack TβRII expression. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by either activated Ras or epidermal growth factor signaling is involved in the down-regulation of TβRII through histone deacetylation. We have immunoprecipitated the protein complexes by biotinylated oligonucleotides corresponding to the HDI-responsive element in the TβRII promoter (-127/-75) and identified the proteins/factors using proteomics studies. The transcriptional repressor Meis1/2 is involved in repressing the TβRII promoter activity, possibly through its recruitment by Sp1 and NF-YA to the promoter. These results suggest a mechanism for the downregulation of TβRII in lung cancer and that TGF-β tumor suppressor functions may be restored by HDIs in lung cancer patients with the loss of TβRII expression.

Introduction

Lung carcinogenesis involves an accumulation of genetic and epigenetic changes leading to functional inactivation of tumor suppressor genes and activation or up-regulation of cellular oncogenes. The loss of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-induced tumor suppressor function in tumors is believed to play a pivotal role in this process. The unresponsiveness to TGF-β could be caused by multiple ways involving both genetic and epigenetic alterations of TGF-β type II receptor expression (TβRII). Mutations within the coding sequence of the TβRII gene are rare in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Mutations in Smad2 and Smad4 genes have been found in 5% to 10% of lung cancers [1,2]. Osada et al. [3] showed that 29 of 33 lung cancer cell lines are unresponsive to TGF-β-induced growth inhibition [4]. TβRII expression was shown to be decreased in 80% of squamous cell carcinoma, 42% adenocarcinoma, and 71% large cell carcinoma [5]. We have shown that the stable expression of TβRII in TGF-β-unresponsive cells restores TGF-β-induced inhibition of cell proliferation, induction in apoptosis, and decrease in tumorigenicity. These findings suggest that cancer cells could result in escape from the autocrine growth-inhibitory effect of TGF-β due to the loss of expression of TβRII [5]. The TβRII promoter has four major regulatory elements: two positive (PRE1 and PRE2) and two negative regulatory elements (NRE1 and NRE2) [6]. Sp1 binds to the TβRII promoter at positions -102 and -59, whereas an inverted CCAAT box in NRE2 at position -83 was identified as NF-Y protein binding site [7,8]. The ets family gene, FLI1, fused with the Ewing sarcoma EWSR1 gene (EWSR1-FLI1) binds to TβRII promoter and suppresses the expression of TβRII [9].

Abnormal histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity and histone acetyl transferase activity in cancers play a major role in deregulating tumor suppressor and tumor promoter genes. HDACs modify histones through deacetylation leading to alterations in chromatin structure. Alteration of HDAC activity is central to the control of cell proliferation by the Myc/Mad and Rb/E2F pathways. The cell cycle regulatory proteins p21Cip1, p16INK4A, and cyclins A and D are regulated by several HDAC inhibitors (HDIs) [10,11]. The HDIs are potent inducers of apoptosis depending on cell types [12]. Trichostatin A (TSA) inhibits hypoxia-induced angiogenesis through reactivation of p53 and VHL and concurrent suppression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and vascular endothelial growth factor [13]. The antitumor activity of the HDI, MS-275, has been reported in in vitro studies and xenograft studies using human tumor cell line [14–16].

Little is known about the mechanism by which the expression TβRII goes down and how TGF-β-mediated antitumor activity can be restored by HDIs in lung cancer. In this study, we demonstrate that TβRII expression is restored by HDIs in lung cancer cell lines lacking TβRII, and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway is important in the down-regulation of TβRII. Using proteomics studies and DNA affinity precipitation assay (DAPA), we have identified a number of factors that are involved in the regulation of TβRII. We have observed that Meis2 represses TβRII promoter activity through binding with Sp1 and NF-Y. Taken together, our results suggest a mechanism for the down-regulation of TβRII and restoration of TGF-β signaling in lung cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

A549, VMRC-LCD, and ACC-LC-176 cell lines were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Activated Ras expressing RIE-inducible Ras (iRas) cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 10% FBS with 150 µg/ml hygromycin B and 200 µg/ml G418.

Reagents and Antibodies

Reagents were purchased as follows: TGF-β1 from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); PD98059, U0126, and anti-Pan Ras from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); and isopropylthio-β-galactoside (IPTG), 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine (AZA), and TSA from Sigma Biochemicals (St Louis, MO). Antibodies were purchased as follows: anti-phospho-ERK from Cell Signaling (Denver, MA); anti-acetylated histone H3/H4 from Upstate Biotechnology (Waltham, MA); and anti-p21Cip1, anti-Smad4, anti-TβRII, anti-ERK, anti-Sp1, anti-NF-YA, and anti-MEIS-2 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

VMRC-LCD, ACC-LC-176, and A549 cells were treated with HDIs and/or DNA methylation inhibitor (AZA) for 24 hours. Total RNA was isolated, and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis for amplification of human TβRII gene fragment (493 base pair) was performed as described previously [5].

Expression Plasmids for NF-YA and Meis2 and TβRII HDI-Responsive Element Promoter Constructs

RT-PCR analyses were performed using primers 5′-AAGCTTACCATGGAGCAGTATACAGCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCGACGGACACTCGGATGATCTGTGT-3′ (reverse) to amplify the coding region of NF-YA gene and primers 5′-AATATAAGCTTGGGATGGACGGAGTAGGGGTTC-3′ (forward) and (5′-CTGACCTCGAGCATGTAGTGCCATTGCCCATCC-3′) (reverse) for the Meis2 gene. RT-PCR products were cloned into pcDNA3-HA vector. To determine the role of the HDI-responsive element (HRE) on TβRII promoter activity and inducibility, the -115/-64 region of TβRII promoter was subcloned into pGL3 basic vector using a set of specific forward and reverse oligo primers (Figure W3) to generate a wild-type (WT) HRE, Sp1 site mutant, NF-YA site mutant, and both Sp1 and NF-YA site mutant constructs.

Transcriptional Response Assay

VMRC-LCD cells were cotransfected with CMV-β-gal and p3TP-Lux or (CAGA)9 MLP-Luc plasmids together with other expression plasmids. Cells were incubated with 5 ng/ml of TGF-β1 with TSA (250 nM) in 0.2% FBS for 22 hours. ACC-LC-176 cells were cotransfected with TβRII promoter luciferase constructs and CMV-β-gal. Transfected cells were treated with TSA (250 nM), MS-275 (500 nM), and/or AZA (1 µM) for 22 hours, and luciferase activities were measured as described previously [17].

Western Blot Analyses

RIE-iRas cells were treated with 5 mM IPTG in the presence of TSA (250 nM). RIE-iRas cells were also treated with 5 nM IPTG in the presence of TSA, PD98059, or U0126. RIE cells were serum starved and treated with epidermal growth factor (EGF) in the presence of TSA or U0126 for 24 and 48 hours. Preparation of cell lysates and Western blot analyses were performed as described previously [17].

[3H]thymidine Incorporation Assay

A549 (15,000 cells/well) and VMRC-LCD (30,000 cells/well) cells were treated with increasing doses of TSA in the presence of 10% FBS/medium for 44 hours. VMRC-LCD cells were also treated with TSA in the presence of SB-431542 (5 µM). [3H]thymidine (4 µCi/well) was added in each well for an additional 4 hours, and cells were then processed for thymidine incorporation assay as described previously [18].

Soft Agarose Assay and Xenograft Studies

A total of 15 x 103 cells (A549 or VMRC-LCD) were plated for soft agarose assay as described before [17]. TSA and/or SB-431542 (5 µM) were added on the top agar layer every third day, and after 10 days, colonies were counted. Each data point is a representative of an average of three independent values. ACC-LC-176, VMRC-LCD, and A549 cells (4 x 106) were injected subcutaneously in BALB/c athymic nude mice. TSA was administered by intraperitoneal injection everyday until sacrifice. Tumor volumes were measured as before.

DNA Affinity Precipitation Assay

The single-stranded 5′-biotinylated oligonucleotides corresponding to the TβRII promoter region (-127/-65, WT oligos) and the mutant sequence (MT oligos, mutated Sp1, and NF-Y binding sites) were purified, annealed, and then used for DAPA as described [19]. Briefly, 1.5 µg of biotin end-labeled double-strand oligonucleotides was incubated with 1 mg of nuclear extracts from untreated or TSA-treated ACC-LC-176 cells in DAPA buffer on ice for 1 hour. The DNA-protein complexes were precipitated with 50 µl of streptavidin-agarose beads, and complexed proteins were detected by Western blot analyses.

Proteomics Analyses

The DAPA experiments were performed with a larger amount of nuclear extracts (∼2.0 mg) from ACC-LC-176 cells. DNA-protein complexes were precipitated and resolved in a 10% SDS-PAGE. Protein regions in each lane were cut, digested in-gel by trypsin or chymotrypsin, extracted, and analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using an LTQ ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher, San Jose, CA) at the Vanderbilt University Proteomics Laboratory. The MS/MS analysis of the peptides was performed using data-dependent scanning in which one full MS spectrum was followed by three MS/MS spectra. The data were searched with the Myrimatch algorithm (v1.6.75) [20] using a human database created from the UniProtKB database (v155). The data were filtered with the IDPicker algorithm (v2.6.165.1) [21,22] using a 5% false discovery rate (FDR) (determined using reverse sequence hits), requiring at least two unique peptides per protein and parsimonious analysis to report a minimal list of proteins. A more detailed description of LC-MS/MS methods can be obtained on request. Specific proteins were further verified by DAPA.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using paired t test. The paired t test was used to assess the significance of differences in vehicle control and treated data points. Values were considered to be statistically significant when P < .05.

Results

HDIs Restore TGF-β-Mediated Tumor Suppressor Function by Inducing TβRII Expression

To determine whether reduced expression of the TβRII gene is responsible for blocking TGF-β signals in VMRC-LCD cells, we used two TGF-β-responsive reporters, p3TP-Lux and (CAGA)9 MLP-Luc (Figure 1A). Both reporters were induced by TGF-β in the presence of TSA but not in the absence of TSA (Figure 1A). Dominant-negative type II receptor (DN-RII) blocked TGF-β-induced reporter activity in the presence of TSA, and constitutively active type I receptor (Act-RI) activated the transcriptional responses in the absence of TSA and TGF-β, suggesting that this cell line has intact TGF-β/Smad signaling downstream of TβRII and that the HDIs can restore TGF-β signaling in the cells lacking TβRII expression. We also observed similar restoration of TGF-β signaling by HDIs in the ACC-LC-176 cell line lacking TβRII expression (data not shown). To test how VMRC-LCD cells (with down-regulation of TβRII) and A549 cells (with functional TβRII) respond to TSA-induced growth arrest, [3H]thymidine incorporation assay was performed. VMRC-LCD cells show stronger inhibition of thymidine incorporation by TSA than that of A549 cells (Figure 1B, left panel). To determine whether TSA uses endogenous TGF-β signaling to inhibit growth, we performed thymidine incorporation assay after treating cells with either TGF-β alone or TSA in the presence of SB-431542, an inhibitor of TGF-β signaling (Figure 2B, right panel). TGF-β had no effect on thymidine incorporation in this cell line. Treatment of cells with TSA decreased the thymidine incorporation in a dose-dependent manner, which was partially blocked by SB-431542, suggesting that restoration of endogenous TGF-β signaling by TSA is required for its full growth inhibition effects. We next tested in vitro whether TSA can reduce tumorigenicity of A549 cells that have intact TGF-β signaling and VMRC-LCD cells that lack TβRII expression (Figure 1C, left panel). We have observed that TSA reduces colony formation by only 10-fold in A549 cells, whereas a 91-fold reduction in colony formation is observed in VMRC-LCD cells. To determine whether endogenous TGF-β signaling is involved in the antitumor effects of the HDIs, we performed soft agar assay using ACC-LC-176 cells lacking TβRII (Figure 1C, right panel). Treatment with TSA reduces the colony numbers and SB-431542 partially blocks the effects of TSA on reducing colony formation. To test this in vivo, we performed xenograft formation studies with (A549) or without (ACC-LC-176 and VMRC-LCD) TβRII expression (Figure 1D). We observed stronger tumor regression by TSA in mice injected with ACC-LC-176 (left panel) or VMRC-LCD (middle panel) cells than that in mice injected with A549 cells (Figure 1D, right panel). Taken together, our data suggest that HDIs can restore TGF-β-induced tumor suppressor function through the induction of TβRII expression.

Figure 1.

Restoration of TGF-β-induced tumor suppressor functions by TSA. (A) VMRC-LCD cells were transiently cotransfected with CMV-β-gal, p3TP-Lux or (CAGA)9 MLP-Luc plasmids, together with the indicated expression plasmids. Cells were treated with TGF-β alone or both TGF-β and TSA. Normalized luciferase activity was expressed as the mean ± SD of triplicate measurements. *P < .05 compared with the corresponding control. **P < .05 when compared between the two data points. ***P < .05 when compared with the corresponding control. (B) Thymidine incorporation assay: A549 and VMRC-LCD cells were treated with increasing amounts of TSA (left). VMRC-LCD cells were also treated with increasing doses of TSA in the presence or absence of SB-431542 (SB) (right). Radioactivity incorporated without TSA treatment is considered as 100%, and the results are expressed as the mean ± SD. *P < .05 compared with the corresponding control. ΔP < .05 and ΔΔP < .05 compared with the corresponding SB treatment. (C) Soft agarose assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. In addition, 5 x 103 ACC-LC-176 cells were plated on soft agar as described above except that TSA and/or SB-431542 were added on the top agar layer every third day. Each data point represents the number of colonies from an average of three values. *P < .05 compared with the corresponding control. **P < .05 when compared between the two data points. (D) In vivo tumorigenicity assay: ACC-LC-176, VMRC-LCD, and A549 were injected subcutaneously behind the anterior fore limb of BALB/c athymic nude mice. TSA (25 µg/d per mice) was administered intraperitoneally. Growth curves are plotted from the mean volume ± SD of tumors from six mice in each group. *P < .05 compared with the corresponding control.

Figure 2.

The HDIs restore TβRII expression in VMRC-LCD (A) and ACC-LC-176 (B) cells but not in A549 (C) cells. Human lung tumor cell lines, VMRC-LCD, ACC-LC-176 (without TβRII expression), and A549 (with TβRII expression), were treated with HDIs and AZA. RT-PCR analyses for TβRII gene expression were performed with total RNA as described previously [5].

HDIs Restore TβRII Expression in VMRC-LCD and ACC-LC-176 Cells

To determine whether HDIs, including MS-275, depsipeptide, TSA, and sodium butyrate, and the methylation inhibitor AZA can induce TβRII mRNA expression, we performed semiquantitative RT-PCR analyses using lung tumor-derived VMRC-LCD and ACC-LC-176 cell lines without TβRII expression and A549 cell line with TβRII expression (Figure 2). Treatment with HDIs increases TβRII mRNA expression in VMRC-LCD (Figure 2A) and ACC-LC-176 (Figure 2B) cells but not in A549 cells (Figure 2C). AZA has no effect on the TβRII promoter activity alone or in combination with HDIs. These data suggest that the HDIs induce TβRII mRNA expression in lung tumor cell lines that lack TβRII expression, and DNA hypermethylation is not involved in this process.

Activation of the MAPK/ERK Pathway Is Involved in the Down-regulation of TβRII through Histone Deacetylation

Activation of K-Ras [23] and up-regulation or activation of EGF receptor (EGFR) in NSCLC [24] is associated with the activation of MEK/ERK pathway. To examine the effect of oncogenic Ras on TβRII expression, we used inducible RIE-iRasV12 stable cell line where IPTG can induce activated Ras expression. TβRII expression is downregulated in a time-dependent manner with increasing levels of activated Ras expression (Figure 3A). In an attempt to determine whether oncogenic Ras-mediated repression of TβRII expression is through histone deacetylation, we observed that TβRII expression is restored by TSA that increases the levels of acetylated histone H3 and H4 (Figure 3B). To determine whether activation of MAPK/ERK pathway is involved in Ras-induced down-regulation of TβRII, we performed Western blot analyses after treating the cells with IPTG and either TSA, PD98059, or U0126 (Figure 3C). These inhibitors efficiently blocked Ras-mediated downregulation of TβRII. To examine whether EGF-induced activation of MEK/ERK pathway can downregulate TβRII expression, RIE cells were treated with EGF in the presence of TSA or U0126. EGF significantly downregulates TβRII expression in these cells within 48 hours, and TSA or U0126 can restore the TβRII expression (Figure 3D). These experiments suggest that sustained activation of MAP/ERK pathway either by activation of Ras or by EGF signaling causes down-regulation of TβRII through the recruitment of HDAC activity.

Figure 3.

TSA treatment restores Ras- and EGF-mediated down-regulation of TβRII expression. (A) Lysates from RIE-iRas cells treated with 5 mM IPTG were analyzed by Western blots using anti-TβRII and anti-Pan-Ras antibodies. (B) Lysates from RIE-iRas cells treated with IPTG in the presence or absence of TSA for indicated times were analyzed by Western blots using anti-TβRII, anti-Ac-histone-H3, anti-Ac-histone-H4, and anti-β-actin antibodies. (C) Lysates from RIE-iRas cells treated with IPTG in the presence of TSA, PD98059, or U0126 for 24 and 48 hours were analyzed by Western blot analyses. (D) Lysates from parental RIE cells treated with EGF (10 ng/ml) in the presence of TSA or U0126 for 24 and 48 hours were analyzed by Western blots.

TβRII Promoter Region (-127/-75) Is Required for Its Activation by the HDIs, MS-275, and TSA

To determine whether increased expression of TβRII mRNA by the HDIs is due to the activation of TβRII promoter, we performed transient transfection assays with serial deletion of 5′-promoter constructs into ACC-LC-176 cells and then treated with MS-275, TSA, or AZA (Figure 4A). The WT constructs show low basal activity, and either MS-275 or TSA efficiently induced the promoter activity when the -127/-75 region remains intact in the TβRII promoter constructs. MS-275 is stronger than TSA in inducing TβRII promoter activity, and AZA alone or in combination with MS-275 or TSA has no effect (Figure 4B). Interestingly, the promoter region -127/-75 contains Sp1 and NF-YA binding sites. Therefore, these results suggest that the promoter region -127/-75 containing Sp1 and NF-YA binding sites is required for MS-275- and TSA-mediated induction of TβRII promoter.

Figure 4.

The promoter region of TβRII (-127/-75) is required for its induction by MS-275 and TSA. (A) A schematic diagram representing the multiple regulatory elements within the TβRII promoter. The TβRII promoter luciferase constructs and β-gal plasmid were transiently cotransfected into ACC-LC-176 cells. Transfected cells were treated with TSA, MS-275, and/or AZA (B). Luciferase activity was normalized and expressed as the mean ± SD. *P < .05 and **P < .05 compared with the corresponding control.

Identification of Proteins Involved in the Regulation of TβRII Expression Using Proteomics Studies

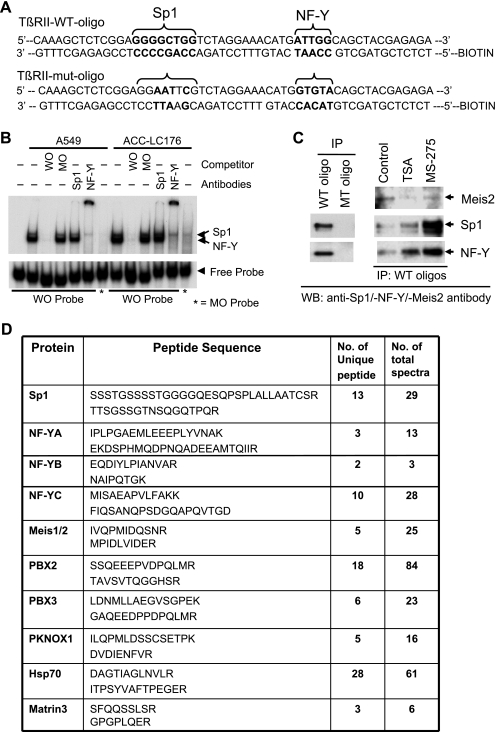

To determine whether Sp1 or NF-YA binds to the Sp1 site or inverted CCAAT box, respectively, in the HRE region (-127/-75, HRE), we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) using nuclear extract from A549 and ACC-LC-176 cell lines (Figure 5B). Sp1 and NF-YA bind to the WT probe but do not bind to the mutant oligo (MO) probe. A cold competition with WT HRE completely abolished the complexes, whereas competition with cold mutant oligo has no effect, suggesting the specific binding of Sp1 and NF-YA to HRE in TβRII promoter. This is confirmed by supershift assays using Sp1 or NF-YA antibodies (Figure 5B). To get a better idea about the identity of proteins involved in the down-regulation of TβRII and to determine the factors involved in restoring TβRII expression by HDIs, we performed proteomics studies after immunoprecipitating the complex using biotinylated double-stranded oligonucleotides corresponding to HRE. First, to test the specificity of binding and in immunoprecipitating the complex, biotinylated WT oligo corresponding to HRE sequence or mutant sequence (mutated Sp1 and NF-YA binding sites; Figure 5A) was incubated with precleared nuclear lysate, and DNA-bound protein complexes were subjected to Western blot analyses (DAPA). The WT oligonucleotide immunoprecipitated both Sp1 and NF-YA, whereas the mutant oligonucleotide did not (Figure 5C, left panel). To test the effect of HDIs on DNA binding affinity, we performed DAPA after treating cells with either MS-275 or TSA. We observed that the HDIs increased binding of Sp1 and NF-YA to the DNA, and there was no appreciable change in the amount of immunoprecipitated Meis2 (identified by proteomics studies). For mass spectral analyses, immunoprecipitated protein complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE, digested with trypsin or chymotrypsin and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The sequence of each peptide was confirmed by MS/MS analyses, thus demonstrating the identity of immunoprecipitated proteins (Figure 5D). The number of unique peptides and the number of total spectra including two representative peptides for each protein detected by LC-MS/MS are shown (Figure 5D). Thus, we successfully identified a number of unique proteins that were precipitated by WT HRE and not by the mutated oligonucleotide.

Figure 5.

Identification of proteins that bind to HRE of TβRII promoter. (A) The WT and mutated (Sp1 and NF-YA sites mutated) oligonucleotide sequences containing HRE in the TβRII promoter are shown. (B) An EMSA was performed using 32P-labeled WT oligo (-115/-64 of TβRII promoter, WO) and mutant oligo probes by incubating nuclear lysates from A549 and ACC-LC-176 cells. In competitive binding or supershift assays, unlabeled WO or MO or antibodies against Sp1 or NF-Y was preincubated with the nuclear extract. DNA-protein complexes were resolved in a 5% native acrylamide gel. (C) Biotinylated double-stranded oligo corresponding to the -127/-65 sequence (WT oligo) or mutant oligo (MT oligo) was mixed with equal amounts of nuclear extracts prepared from ACC-LC-176 cells treated with TSA or MS-275. DNA-protein complexes were precipitated with streptavidin-agarose beads and subjected to Western blot analyses for Sp1, NF-YA, and Meis2. (D) DAPA was performed using WT and mutant oligos for proteomics studies. DNA-protein complexes were precipitated and resolved in 10% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were eluted, digested with trypsin or chymotrypsin, and finally analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The number of unique peptides and the number of total spectra including two representative peptide sequences for each protein detected by MS are shown.

Meis2 Represses Transcription through the Interaction with Sp1 and NF-YA

The homeodomain transcriptional repressors, Meis1/Meis2, were identified as coprecipitating proteins with the HRE oligonucleotide. To test the role of Meis proteins in the regulation of TβRII promoter, we have stably expressed Meis2 in ACC-LC-176 cell line (Figure W1). We transfected TβRII promoter constructs (-1887/+50 and -370/+50) and HRE-containing luciferase constructs (WT and Sp1/NF-YA double mutant, described below) in vector control or Meis2-overexpressing cells. Both TβRII promoter reporters and WT HRE reporter were strongly induced by MS-275 that was abrogated by Meis2. Mutations in Sp1 and NF-YA binding sites in HRE abolished HDI (MS-275) inducibility (Figure 6A). MS-275 and TSA induces Sp1-dependent transcription in ACC-LC-176 cells (Figure W2B). The Sp1-DNA binding inhibitor mithramycin inhibited TβRII promoter activity induced by MS-275 (Figure W2A), suggesting a role of Sp1 in HDI-induced TβRII promoter activity. To determine the role of Sp1 and NF-YA binding sites in HRE in HDI-mediated induction in TβRII promoter activity, we generated reporter constructs with one copy of WT HRE, mutated Sp1 binding site (HRE Sp1 mutant), mutated NF-YA binding site (HRE NF-YA mutant), and mutated Sp1/NF-YA binding sites. Mutation in either Sp1 or NF-YA site dramatically decreased the MS-275-induced luciferase activity when compared with that of WT HRE reporter activity (Figure 6B). To test whether EGF can affect MS-275-mediated TβRII reporter activation, we performed transcription assays using above HRE reporter constructs as described in Figure 6B. We observed that MS-275 treatment induced TβRII reporter activity, whereas treatment with EGF significantly reduced this activation (Figure 6C). However, mutations in either Sp1 or NF-YA or both SP1/NF-YA sites in the TβRII promoter dramatically reduced reporter activities that were not affected significantly either by MS-275 or EGF treatment (Figure 6C), suggesting that the EGF-mediated MEK/ERK signaling might be involved in regulating Sp1 and NF-YA-dependent transcriptional activity. Together, these results suggest that both Sp1 and NF-YA sites are required for synergistic increase in HRE reporter activity by HDIs, and Meis2 is involved in the repression of HDI-inducible TβRII promoter activity.

Figure 6.

Meis2 inhibits HDI-induced TβRII promoter activity. (A) Vector control and Meis2-overexpressing ACC-LC-176 clones were transiently cotransfected with CMV-β-gal and TβRII promoter reporter plasmids. Transfected cells were treated with MS-275, and the normalized relative luciferase activities are shown. *P < .05 compared with the corresponding control. **P < .05 compared between corresponding treatment points. (B) ACC-LC-176 cells were transiently cotransfected with CMV-β-gal and various plasmid constructs that contain WT HRE, HRE (Sp1 mutant), HRE (NF-YA mutant), or HRE (double mutant). Transfected cells were treated with MS-275, and the relative luciferase activities are shown. *P < .05 compared with the corresponding control. **P < .05 compared with the corresponding WT treatment point. (C) ACC-LC-176 cells were transiently cotransfected with CMV-β-gal and various plasmid constructs as described above. Transfected cells were treated with MS-275 with or without EGF (10 ng/ml), and the relative luciferase activities are shown. *P < .05 compared with the corresponding control. **P < .05 compared with corresponding treatment points. ΔP < .05 when compared with the WT treatment point. (D) Meis2 physically interacts with Sp1 and NF-YA. 293T cells were cotransfected with Meis2-HA and Sp1-Flag (left) or Meis2-Flag and NF-YA-HA (right panel) expression vectors. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Flag or anti-HA antibodies, and the presence of Meis2 in the complex was detected by Western blot analysis. Expressions of Meis2-HA, Meis2-Flag, Sp1-Flag, and NF-YA-HA proteins were determined (bottom panels). (E) Hypothetical model for the loss of TGF-β tumor suppressor function in lung cancer. Up-regulation/activation of EGF receptor (EGFR) and/or oncogenic activation of Ras in lung cancer result in the activation of MEK/ERK pathway that leads to down-regulation of TβRII. MEK1/2 inhibitors block the down-regulation of TβRII induced by activated Ras or EGFR. The reduced level of TβRII is due to the recruitment of HDAC activity on the promoter by transcription factors (TF) with subsequent replacement of histone acetyl transferase proteins including p300 and CBP. TGF-β-induced tumor suppressor function may be restored by treatment with HDIs in lung tumors that are resistant to TGF-β due to the loss of TβRII expression.

Although Meis2 was immunoprecipitated by HRE in the DAPA assay (Figure 5C), we did not detect any DNA-protein complex formation with Meis2 in EMSA (data not shown). To verify whether Meis2 was coprecipitated with Sp1 and/or NF-YA in the DAPA experiment, we tested whether Meis2 could interact with Sp1 and/or NF-YA in immunoprecipitation and Western blot analyses. Tagged (HA or Flag) Meis2 was cotransfected with either Sp1-Flag or NF-YA-HA into 293T cells. Meis2 was detected in the immune complexes of either Sp1 (Figure 6D, left panel) or NF-YA (right panel), and in both cases, the amount of coimmunoprecipitated Meis2 was not affected by TSA or MS-275 treatment. Taken together, these results suggest that Meis2 may repress transcription of TβRII through the interaction with Sp1 and NF-YA.

Discussion

The resistance to TGF-β-mediated tumor suppressor functions could be caused by multiple ways involving both genetic and epigenetic changes in TGF-β signaling molecules. However, mutations within the coding sequence of the TβRII gene are rare in NSCLC. Mutations in Smad2 and Smad4 genes have been found in 5% to 10% of lung cancers [18,19]. In the present study, we have observed that HDIs and not azacytidine can restore TβRII expression in lung cancer VMRC-LCD and ACC-LC-176 cell lines lacking TβRII expression but not in A549 cells having TβRII expression. These results suggest that the cellular machinery in VMRC-LCD and ACC-LC-176 cell lines recruit the HDAC activity to repress the transcription of TβRII, and three structurally different HDIs restore this expression (Figure 2). This is supported by the findings that HDIs induce TβRII promoter activity and azacytidine cannot (Figure 4). As a functional consequence of TβRII expression by HDIs, TGF-β signaling has been restored by HDIs (Figure 1A). The dominant-negative type II receptor blocked TGF-β-induced reporter activity in the presence of TSA, and constitutively, active type I receptor activated the transcriptional responses in the absence of TSA and TGF-β. Therefore, this cell line has intact TGF-β/Smad signaling downstream of TβRII, and treatment of these cells with HDI restores TGF-β signaling through reexpression of TβRII. Similar restoration of TGF-β signaling by HDIs was observed in ACC-LC-176 (data not shown). Restoration of TGF-β signaling in VMRC-LCD cell line by HDI makes this cell line sensitive to TGF-β-induced growth inhibition (Figure 1B), which is partially attenuated by the specific inhibitor SB-431542 (Figure 1B, right panel), suggesting the restoration of endogenous TGF-β signaling by HDIs. Similarly, TSA strongly decreases the colony-forming ability of VMRC-LCD cells, which is partially blocked by SB-431542 (Figure 1C). This suggests that TGF-β signaling plays an important role in the antitumor effects of HDIs particularly when TβRII expression is reduced through HDAC inhibition. This is further supported by the in vivo studies where stronger tumor regression by TSA using ACC-LC-176 or VMRC-LCD cells was observed when compared with A549 cells (Figure 2D).

K-Ras is known to be mutated in around 30% of primary NSCLCs [23]. The up-regulation or activation of EGFR in NSCLC (∼78%) is associated with the activation of ERK1/2 [24]. Activation of Ras downregulates TβRII expression (Figure 3A) and activated Ras-induced down-regulation of TβRII promoter activity is attenuated by HDIs (data not shown), suggesting that histone deacetylation in activated Ras cell line has a role in decreasing TβRII promoter activity. This is supported by the fact that activated Ras- and EGF-induced downregulation of TβRII is inhibited by HDIs, and TβRII expression is restored (Figure 3). This down-regulation of TβRII is blocked by MEK/ERK pathway inhibitors (Figure 3C). Together, activation of MEK/ERK pathway by mutated Ras or EGF is involved in the down-regulation of TβRII through the recruitment of HDAC activity.

Currently, there is no available literature about the interaction between oncogenic Ras and epigenetic regulation of TβRII expression in lung cancer. However, a study showed that activation of Ras-MAPK pathway by the expression of oncogenic Ras increases nuclear localization of HDAC4 in C2C12 myoblast cells [25]. Furthermore, ERK1/2 was found to be associated with HDAC4 in the nucleus and phosphorylate it, suggesting that the chromatin-modifying enzyme HDAC4 is a target of the Ras-MAPK signaling pathway [25]. Another study demonstrated that reduced E-cadherin expression through histone deacetylation plays an important role in developing resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as gefitinib and erlotinib. Enhanced E-cadherin expression by exposure to HDI, MS-275, induces sensitivity to gefitinib in resistant NSCLC cell lines [26]. This study suggests a synergistic effect on growth inhibition and apoptosis from sequential treatment with MS-275 and gefitinib. Thus, the sequential combination of HDIs and EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors may provide a new therapeutic strategy for NSCLC patients. Although nothing is known about the role of targeted therapies against EGFR, Ras, or MAPK on TβRII expression in lung cancer, this study suggests that the inhibition of MAPK/ERK pathway may restore TGF-β-induced tumor suppressor functions in NSCLC patients through the expression of TβRII.

One of the most informative parts of this study is to identify factors that bind directly or indirectly to HRE in TβRII promoter region. The identity of each protein has been confirmed by two or more peptide sequences. Binding of Sp1 and NF-YA (Figure 5D, observed in proteomics studies) was confirmed by EMSA and DAPA assays, which supports the specificity of binding of other proteins to the HRE sequence. Sp1 and NF-YA binding to HRE is enhanced in response to HDIs, suggesting that binding of these factors may be important in HDI-mediated TβRII promoter induction. Proteomics studies have shown the coprecipitation of Meis1 and Meis2 by HRE sequence. Meis1 and Meis2 can bind canonical TGAC-3′ site [27]. Because there is TGGC-3′ sequence within HRE, it is tempting to hypothesize that they bind to this sequence. However, we do not observe such binding in the EMSA with HRE as a probe (data not shown). Interestingly, our data indicate that Meis2 interacts with Sp1 and NF-YA, suggesting that Meis2 may be coprecipitated through this protein-protein interaction. In an attempt to understand the functional outcome of this interaction, we have observed that Meis2 represses HDI-induced TβRII transcription through the HRE. Sp1 [28] and/or NF-YA [29] can recruit HDAC to the promoter and causes chromatin condensation leading to transcriptional repression. It is possible that Meis2 may help to recruit HDAC activity on to the TβRII promoter through the interaction with Sp1 and NF-YA, thus leading to TβRII down-regulation. In addition to Meis proteins, other TALE homeobox proteins like PBX2/3 and pKnox1 are also coprecipitated with WT HRE. The N-terminal domain of Pbx interacts with either Meis or pKnox forming a heterodimer that cooperatively binds to the TGAT-TGAC sequence [28], where Pbx proteins bind to the TGAT motif and Meis or pKnox proteins bind to the TGAC element. It is possible that Pbx-Meis or Pbx-pKnox complexes bind to the TGAT-TGGC element on the TβRII promoter that overlaps with the NF-YA binding element, inverted CCAAT box. These complexes may recruit corepressors or HDACs and repress transcription of TβRII, which is consistent with a previous study [30]. The HDIs could activate transcription through the activation of coactivators or the replacement of HDAC activity. Another scenario for the regulation of TβRII promoter activity could be due to the competition between the Pbx-Meis/pKnox complex and the NF-YA complex for binding the overlapping sequence. Future studies will address these different levels of transcriptional complexity in regulating TβRII expression in lung cancer.

TGF-β signaling plays an important role in the development of most human solid tumors in advanced stages, and numerous studies support targeting TGF-β signaling as therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment. Although, to date, several approaches have been developed for blocking TGF-β signaling pathways and several drugs have been developed that are either in nonclinical or in early stages of clinical investigation, the small-molecule inhibitors of TGF-β signaling could be very useful for the development of therapeutic strategies for treatment of human cancers [18,31]. The most desirable approach for developing a new therapeutic strategy by targeting TGF-β signaling would be to retain TGF-β-induced tumor-suppressor functions but to block TGF-β-mediated prooncogenic signaling in advanced invasive and metastatic cancers. Most TGF-β signaling small-molecule inhibitors target to the kinase domain of TβRI, which differs considerably from that of TβRII, thus giving specificity for inhibition of TβRI versus TβRII signaling. The main strategy for inhibition of the TGF-β signaling pathway is to include compounds that interfere with the binding of TGF-β to its receptors, drugs that block intracellular signaling, and antisense oligonucleotides. Strategies that block catalytic activity of TβRI including the small molecules such as SB-431542 and SB-505124 (GlaxoSmithKline), SD-093 and SD-208 (Scios), and LY580276 (Lilly Research Laboratories), act as competitive inhibitors for the ATP-binding site of TβRI kinase [32]. Studies with pan-TGF-β-neutralizing antibodies and soluble TβRII-Fc fusion protein suggest that suppression of tumor progression by blocking TGF-β signaling network may provide an attractive target for therapeutic intervention [33,34]. Studies with soluble Fc:TβRII, used either as an injectable drug [34] or when stably expressed as a transgene [35], antagonize TGF-β signaling and reduce mammary tumor metastasis to the lung. Thus, TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitors might be useful in developing therapeutic strategies for human cancers. However, the main challenge will involve identifying the appropriate patients for therapy to ensure that targeted tumors are refractory to TGF-β-induced tumor suppressor functions but responsive to tumor-promoting effects of TGF-β.

In summary, our study has demonstrated, for the first time, the identification of a number of proteins/factors involved in the regulation of TβRII in lung cancer cell lines and how Meis proteins may be involved in the loss of TβRII expression. This study provides an important clue about how activation of MAPK/ERK pathway plays a role in the down-regulation of TβRII through histone deacetylation. In addition, TGF-β-induced tumor suppressor function is restored in TGF-β-resistant lung cancer cells by HDIs. Because most lung tumors are resistant to TGF-β because of the loss of TβRII through histone deacetylation, HDAC inhibitors may have potential for therapeutic intervention either alone or in combination with other agents.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This study was supported by R01 CA95195 and CA113519, National Cancer Institute SPORE grant in lung cancer (5P50CA90949, project no. 4), and Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award (to P.K.D.). The authors thank Dr Takashi Takahashi (Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute, Nagoya, Japan), Dr R. Daniel Beauchamp (Vanderbilt University Medical Center), and Dr Jonathan Yingling (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) for providing plasmids and reagents. The authors do not have any conflict of interests.

This article refers to supplementary materials, which are designated by Figures W1 to W3 and are available online at www.neoplasia.com.

References

- 1.Nagatake M, Takagi Y, Osada H, Uchida K, Mitsudomi T, Saji S, Shimokata K, Takahashi T, Takahashi T. Somatic in vivo alterations of the DPC4 gene at 18q21 in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2718–2720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uchida K, Nagatake M, Osada H, Yatabe Y, Kondo M, Mitsudomi T, Masuda A, Takahashi T, Takahashi T. Somatic in vivo alterations of the JV18-1 gene at 18q21 in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5583–5585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osada H, Tatematsu Y, Masuda A, Saito T, Sugiyama M, Yanagisawa K, Takahashi T. Heterogeneous transforming growth factor (TGF)-β unresponsiveness and loss of TGF-β receptor type II expression caused by histone deacetylation in lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8331–8339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hougaard S, Norgaard P, Abrahamsen N, Moses HL, Spang-Thomsen M, Skovgaard Poulsen H. Inactivation of the transforming growth factor β type II receptor in human small cell lung cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1005–1011. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anumanthan G, Halder SK, Osada H, Takahashi T, Massion PP, Carbone DP, Datta PK. Restoration of TGF-β signalling reduces tumorigenicity in human lung cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1157–1167. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae HW, Geiser AG, Kim DH, Chung MT, Burmester JK, Sporn MB, Roberts AB, Kim SJ. Characterization of the promoter region of the human transforming growth factor-β type II receptor gene. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29460–29468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings R, Alsarraj M, Wright KL, Munoz-Antonia T. Regulation of the human transforming growth factor β type II receptor gene promoter by novel Sp1 sites. Oncogene. 2001;20:6899–6909. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly D, Kim SJ, Rizzino A. Transcriptional activation of the type II transforming growth factor-β receptor gene upon differentiation of embryonal carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21115–21124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahm KB, Cho K, Lee C, Im YH, Chang J, Choi SG, Sorensen PH, Thiele CJ, Kim SJ. Repression of the gene encoding the TGF-β type II receptor is a major target of the EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein. Nat Genet. 1999;23:222–227. doi: 10.1038/13854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnstone RW. Histone-deacetylase inhibitors: novel drugs for the treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:287–299. doi: 10.1038/nrd772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks P, Rifkind RA, Richon VM, Breslow R, Miller T, Kelly WK. Histone deacetylases and cancer: causes and therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:194–202. doi: 10.1038/35106079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vigushin DM, Coombes RC. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer treatment. Anticancer Drugs. 2002;13:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim MS, Kwon HJ, Lee YM, Baek JH, Jang JE, Lee SW, Moon EJ, Kim HS, Lee SK, Chung HY, et al. Histone deacetylases induce angiogenesis by negative regulation of tumor suppressor genes. Nat Med. 2001;7:437–443. doi: 10.1038/86507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito A, Yamashita T, Mariko Y, Nosaka Y, Tsuchiya K, Ando T, Suzuki T, Tsuruo T, Nakanishi O. A synthetic inhibitor of histone deacetylase, MS-27-275, with marked in vivo antitumor activity against human tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4592–4597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee BI, Park SH, Kim JW, Sausville EA, Kim HT, Nakanishi O, Trepel JB, Kim SJ. MS-275, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, selectively induces transforming growth factor β type II receptor expression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:931–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaboin J, Wild J, Hamidi H, Khanna C, Kim CJ, Robey R, Bates SE, Thiele CJ. MS-27-275, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase, has marked in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity against pediatric solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6108–6115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halder SK, Beauchamp RD, Datta PK. Smad7 induces tumorigenicity by blocking TGF-β-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2005;307:231–246. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halder SK, Beauchamp RD, Datta PK. A specific inhibitor of TGF-β receptor kinase, SB-431542, as a potent antitumor agent for human cancers. Neoplasia. 2005;7:509–521. doi: 10.1593/neo.04640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao S, Venkatasubbarao K, Li S, Freeman JW. Requirement of a specific Sp1 site for histone deacetylase-mediated repression of transforming growth factor β type II receptor expression in human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2624–2630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tabb DL, Fernando CG, Chambers MC. MyriMatch: highly accurate tandem mass spectral peptide identification by multivariate hypergeometric analysis. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:654–661. doi: 10.1021/pr0604054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang B, Chambers MC, Tabb DL. Proteomic parsimony through bipartite graph analysis improves accuracy and transparency. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:3549–3557. doi: 10.1021/pr070230d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma ZQ, Dasari S, Chambers MC, Litton MD, Sobecki SM, Zimmerman LJ, Halvey PJ, Schilling B, Drake PM, Gibson BW, et al. IDPicker 2.0: improved protein assembly with high discrimination peptide identification filtering. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:3872–3881. doi: 10.1021/pr900360j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim DH, Kim JS, Park JH, Lee SK, Ji YI, Kwon YM, Shim YM, Han J, Park J. Relationship of Ras association domain family 1 methylation and K-ras mutation in primary non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6206–6211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukohara T, Kudoh S, Yamauchi S, Kimura T, Yoshimura N, Kanazawa H, Hirata K, Wanibuchi H, Fukushima S, Inoue K, et al. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and downstream-activated peptides in surgically excised non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Lung Cancer. 2003;41:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou X, Richon VM, Wang AH, Yang XJ, Rifkind RA, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase 4 associates with extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2, and its cellular localization is regulated by oncogenic Ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14329–14333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250494697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Witta SE, Gemmill RM, Hirsch FR, Coldren CD, Hedman K, Ravdel L, Helfrich B, Dziadziuszko R, Chan DC, Sugita M, et al. Restoring E-cadherin expression increases sensitivity to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2006;66:944–950. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knoepfler PS, Calvo KR, Chen H, Antonarakis SE, Kamps MP. Meis1 and pKnox1 bind DNA cooperatively with Pbx1 utilizing an interaction surface disrupted in oncoprotein E2a-Pbx1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14553–14558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doetzlhofer A, Rotheneder H, Lagger G, Koranda M, Kurtev V, Brosch G, Wintersberger E, Seiser C. Histone deacetylase 1 can repress transcription by binding to Sp1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5504–5511. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park SH, Lee SR, Kim BC, Cho EA, Patel SP, Kang HB, Sausville EA, Nakanishi O, Trepel JB, Lee BI, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the transforming growth factor β type II receptor gene by histone acetyltransferase and deacetylase is mediated by NF-Y in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5168–5174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang W, Zhao S, Ammanamanchi S, Brattain M, Venkatasubbarao K, Freeman JW. Trichostatin A induces transforming growth factor β type II receptor promoter activity and acetylation of Sp1 by recruitment of PCAF/p300 to a Sp1.NF-Y complex. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10047–10054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagaraj NS, Datta PK. Targeting the transforming growth factor-β signaling pathway in human cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19:77–91. doi: 10.1517/13543780903382609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yingling JM, Blanchard KL, Sawyer JS. Development of TGF-β signalling inhibitors for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:1011–1022. doi: 10.1038/nrd1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siegel PM, Massague J. Cytostatic and apoptotic actions of TGF-β in homeostasis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:807–821. doi: 10.1038/nrc1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muraoka RS, Dumont N, Ritter CA, Dugger TC, Brantley DM, Chen J, Easterly E, Roebuck LR, Ryan S, Gotwals PJ, et al. Blockade of TGF-β inhibits mammary tumor cell viability, migration, and metastases. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1551–1559. doi: 10.1172/JCI15234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang YA, Dukhanina O, Tang B, Mamura M, Letterio JJ, MacGregor J, Patel SC, Khozin S, Liu ZY, Green J, et al. Lifetime exposure to a soluble TGF-β antagonist protects mice against metastasis without adverse side effects. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1607–1615. doi: 10.1172/JCI15333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.