Abstract

Retropharyngeal abscesses are rare in adults. They occur mostly in immunocompromised patients or as a foreign body complication. We report 5 cases of retropharyngeal abscess collected in the ENT Department of CHU Mohammed VI of Marrakech, during a two-year period (December 2008 to December 2009). Local trauma by foreign body ingestion was the aetiology in four patients. The presenting symptoms, for all patients, were fever, odynophagia, torticollis, and trismus, and the clinical examination showed bulging of the posterior wall of the oropharynx. The radiography of cervical spine showed prevertebral thickening in all cases, this thickening was associated with an aspect of vertebral lysis of the fourth cervical vertebra in one case. A CT scan was performed in all our cases and showed features of retropharyngeal abscess which was associated, in one case, with spondylodiscitis. The biological assessment found one case of diabetes. The intradermal reaction to the tuberculin was clearly positive in one case. Endobuccal abscess puncture was practiced in 4 cases; only one organism was identified by culture: Staphylococcus aureus treatment was based on triple intravenous antibiotics and anti-Koch's therapy (in one case), and the surgical drainage under general anesthesia was also performed in the case of the diabetes patient which required also the correction of hyperglycemia in intensive care unit. The outcome was good in all our patients. The diagnosis of retropharyngeal abscess can be difficult and one must seek a comorbidity; a tuberculosis aetiology must be considered in countries with a high prevalence. The management of these cases is based on antibiotics and surgical drainage.

Keywords: retropharyngeal abscess, adults, antibiotics, tuberculosis, and surgical drainage

1. INTRODUCTION

A retropharyngeal abscess is an infection in one of the deep spaces of the neck. In adults, retropharyngeal abscesses are rare in adults and can occur as a result of local trauma, such as foreign body ingestion (fishbone), or instrumental procedures (laryngoscopy, endotracheal intubation, feeding tube placement, etc.), or in the particular context of an associated disease [1, 2]. These abscesses are more frequent in children because of the abundance of retropharyngeal lymph nodes [2, 3]. Retropharyngeal abscesses require prompt diagnosis and early management which frequently involves surgical drainage to achieve the best results. However, the appropriate timing to undergo a surgical procedure is still controversial [3]. The present study reviews, through five cases of different etiology, our experience in the management of these abscesses.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The clinical records of five consecutive cases admitted at the ENT Department of the University Hospital of Marrakech with a diagnosis of retropharyngeal abscesses between December 2007 and December 2010 were retrospectively reviewed.

Peritonsillar abscesses were excluded. Factors such as sex, age, suspected aetiology, clinical symptoms, physical findings, blood tests, findings on imaging studies, treatment, clinical outcomes, and complications were analyzed.

3. RESULTS

The age range of the five cases was between 18 months and 72 years (3 males and 2 females). Foreign body ingestion was identified in four cases; 3 cases of fishbone and one case of chicken bone (Table 1). All our patients presented with odynophagia, torticollis, trismus, and pyrexia. Clinical examination showed bulging of the posterior wall of the oropharynx in four patients (Figure 1) and pain on the palpation of the transverse spine of the fourth cervical vertebra in one patient. The neurological examination was normal in all our patients. Radiography of the cervical spine showed prevertebral thickening in all our cases (Figure 2), this thickening was associated with a degree of vertebral lysis of the fourth cervical vertebra in one case. Cervical CT showed an isolated retropharyngeal abscess in four cases (Figures 3 and 4) and in the other case a degree of spondylodiscitis, suggestive of Pott's disease (Figure 5). Biological assessment revealed type 2 diabetes in one case and increased white blood cell counts in all cases. The tuberculin test was clearly positive in one case.

Table 1.

Summary of epidemiological data and suspected etiologies.

| Patients | Age | Sex | Etiology | Morbidity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 18 | Male | Chicken bone | |

| Case 2 | 34 | Male | Fishbone | |

| Case 3 | 72 | Female | Fishbone | |

| Case 4 | 46 | Female | Fishbone | Diabetes |

| Case 5 | 38 | Male | Tuberculosis |

Figure 1.

Bulging of the posterior wall of the oropharynx.

Figure 2.

Prevertebral thickening in the radiography of cervical spine.

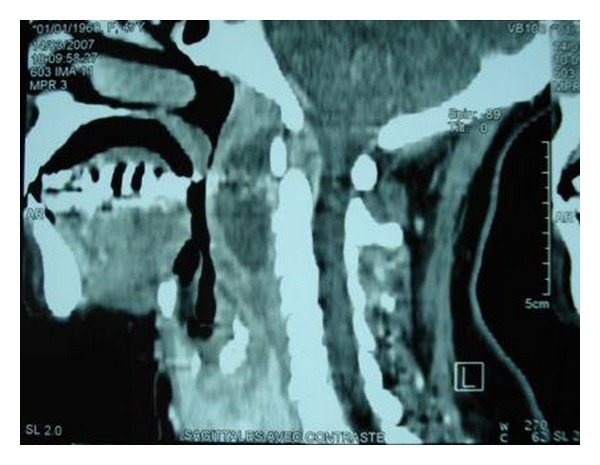

Figure 3.

CT (sagittal view) showing retropharyngeal collection.

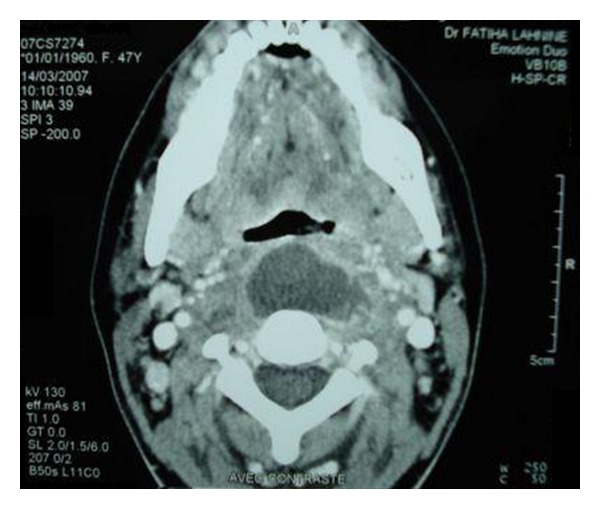

Figure 4.

CT (transversal view) showing retropharyngeal collection.

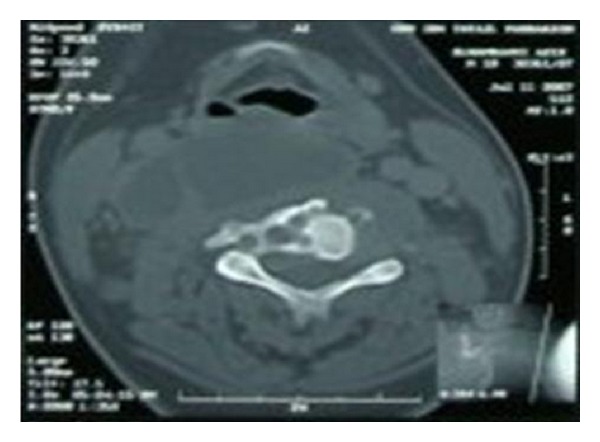

Figure 5.

Aspect of spondylodiscitis of the fourth cervical vertebra.

Intraoral puncture, under local anesthesia, was practiced in 3 cases. In the two remaining cases surgical drainage, under general anesthesia, was performed via oral route (Table 2). Only one organism was identified by culture: Staphylococcus aureus (which was sensitive to our primary antibiotic treatment).

Table 2.

Established treatment.

| Cases | Antibiotics | Anti-Koch's therapy | Puncture | Surgical drainage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | + | + | ||

| Case 2 | + | + | ||

| Case 3 | + | + | ||

| Case 4 | + | + | ||

| Case 5 | + | + |

Upon admission we commenced, in the four cases of foreign body trauma, intravenous antibiotic therapy: Co-amoxiclav, Gentamicin, and Metronidazole, switching to oral administration after 48 hours of apyrexia (after 8 days on average). The total duration of antibiotics was 14 days on average (apart from the case of tubercular origin).

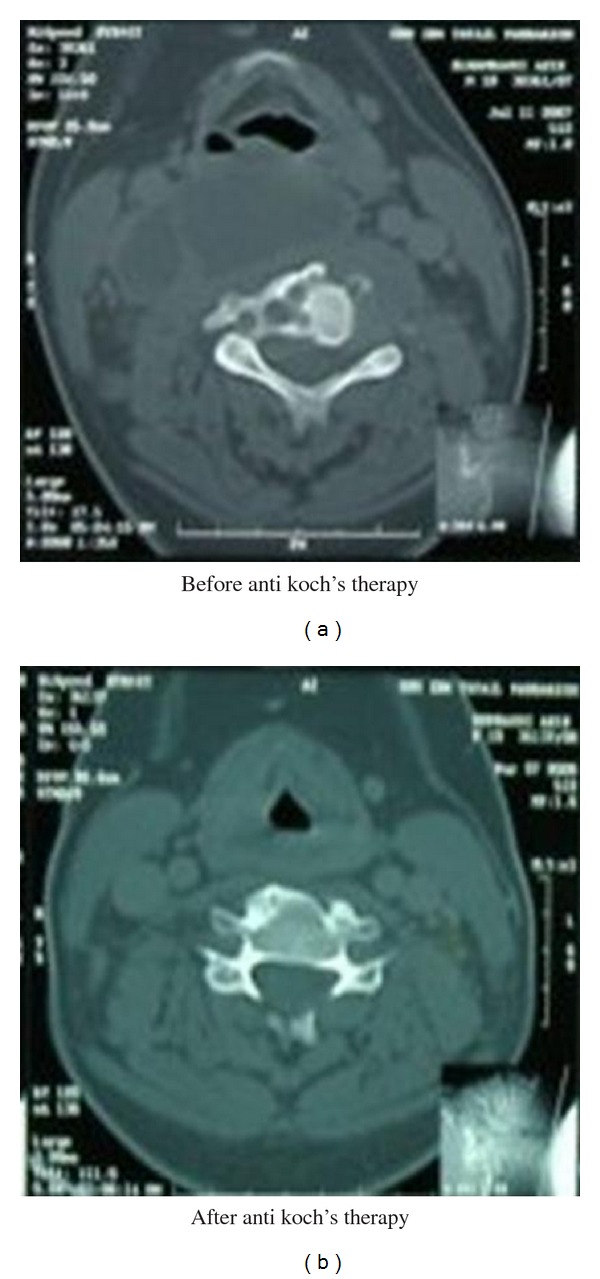

No patient needed the airway securing as a result of respiratory distress. In the case with diagnosis of a retropharyngeal abscess complicating Pott's disease antibiotics were withheld and anti-Koch's therapy was commenced (2 months of Rifampicin, Isoniazid, and Pyrazinamide followed by 7 months of Rifampicin and Isoniazid) after surgical drainage.

The Surgical drainage under general anesthesia was also performed in the case of the diabetic patient who required also the correction of hyperglycemia in intensive care unit.

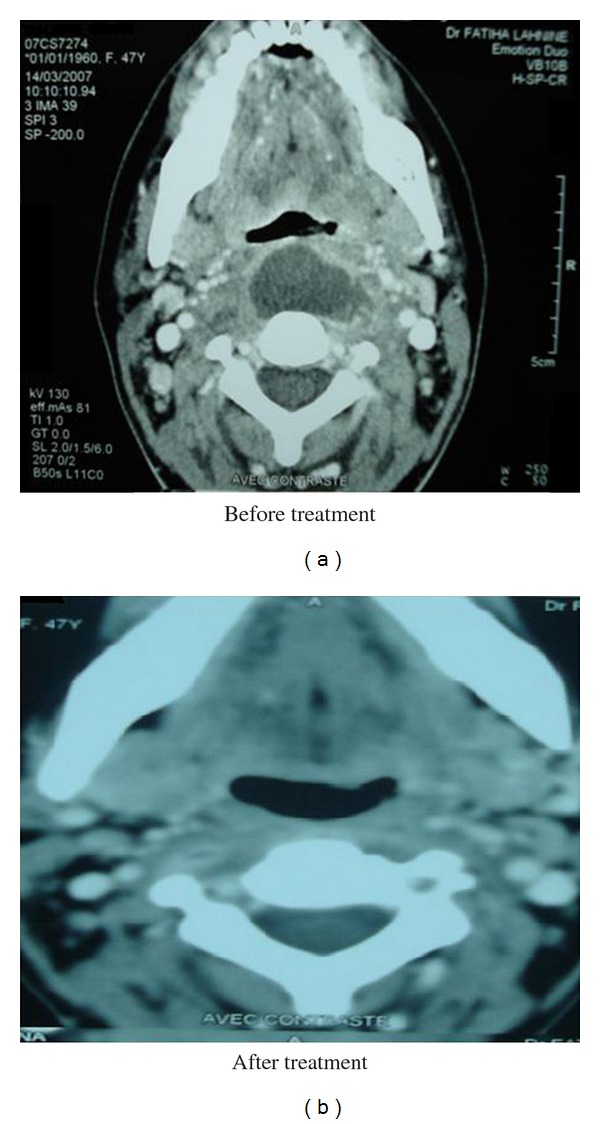

The length of hospital stay varied between 6 and 15 days with an average of 9 days. Every patient was followed for six months, without evidence of recurrence. Cervical CT (after six months) showed resolution of the retropharyngeal collection (Figure 6); however, in one case there was remodeling of the 4th vertebra (the case of tuberculosis origin; Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Disappearance of the retropharyngeal collection after treatment.

Figure 7.

Persisting images of bone remodeling after treatment.

4. DISCUSSION

Retropharyngeal abscesses are deep neck space infections that can pose an immediate life-threatening emergency, with potential for airway compromise and other catastrophic complications [4]. The retropharyngeal space is posterior to the pharynx, bound by the buccopharyngeal fascia anteriorly, the prevertebral fascia posteriorly, and the carotid sheaths laterally. It extends superiorly to the base of the skull and inferiorly to the mediastinum [5].

Abscesses in this space can be caused by many organisms such as aerobic organisms (beta-hemolytic Streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus), anaerobic organisms (species of Bacteroides and Veillonella), or Gram-negative organisms (Haemophilus parainfluenzae and Bartonella henselae) [6]; in our data we isolated one organism: Staphylococcus aureus.

The high mortality rate associated with retropharyngeal abscesses is due to its association with airway obstruction, mediastinitis, aspiration pneumonia, epidural abscess, jugular venous thrombosis, necrotizing fasciitis, sepsis, and erosion into the carotid artery [7]. In a study of 234 adults with deep space infections of the neck in Germany, the mortality rate was 2.6% [8]. The cause of death was primarily sepsis with multiorgan failure. Unlike children, adults abscesses due to nasal or pharyngeal infection are rare and are usually secondary to trauma, foreign bodies, or as a complication of dental infections [9], and, in our study, the principal etiology was fishbone ingestion (3 cases).

Retropharyngeal abscess is more common in males than in females, with generally reported male preponderance of 53–55%. The principal symptoms in adults are sore throat, fever, dysphagia, odynophagia, neck pain and dyspnoea. Patients with retropharyngeal abscesses may present signs of airway obstruction, but often they do not. The most common physical presentation is posterior pharyngeal oedema (37%), nuchal rigidity, cervical adenopathy, drooling, and stridor [10].

The clinical diagnosis of retropharyngeal abscess can be difficult; the clinical symptoms are variable and nonspecific. The signs of infection may be lacking in certain situations of immune suppression such as diabetes [11]; however, in our study, the patient with diabetes was febrile and had trismus with bulging of the pharyngeal wall.

CT contributes greatly to the diagnosis, but it has limitations in differentiating abscess from cellulitis of the retropharyngeal space. The plain radiograph in lateral view is very specific when it shows air in the retropharyngeal space. Carrying out radiological examinations should not delay care [12] and any suspected retropharyngeal abscess should be prescribed antibiotics (which can be altered later).

Cases of tuberculous retropharyngeal abscess have been reported previously [13], and, in our series, we saw one case of retropharyngeal abscess secondary to Pott's disease, treated successfully with anti-Koch's therapy.

According to Lübben et al. [14], cervical spine tuberculosis with a cold retropharyngeal abscess is extremely rare, and it should be suspected in a person who presents with a destructive lesion of the vertebra and a retropharyngeal mass. In our study, the diagnosis of tuberculous retropharyngeal abscess was made before clinical and radiological arguments (image of spondylodiscitis) as well as the positivity of tuberculin test.

In cases of tuberculous retropharyngeal abscesses with neurologic complications, recovery does occur in nearly all the patients following prompt drainage and antituberculous therapy. The treatment of a tuberculous retropharyngeal abscess by drugs alone is hazardous even in the absence of myelopathy [15]. Although there is no consensus in the literature regarding conservative or surgical management of spinal tuberculosis, some authors suggest that surgery should be reserved for cases where the diagnosis is in doubt and there is initial severe or progressive neural deficit with/without respiratory distress in presence of documented mechanical compression and documented dynamic instability following conservative treatment [16].

In nonspecific retropharyngeal abscess, antibiotic therapy (generally triple intravenous antibiotics: Co-amoxiclav, Aminoglycoside, and Imidazole) alone may be insufficient, and most authors recommend combining it with a surgical drainage of the collection [17].

The ideal time to make the drainage is in dispute. Some suggest local antibiotic injection at the same time as surgical drainage. In our study the use of surgical drainage was required in only two cases (cases of diabetes and tuberculosis); in other cases, the puncture of the abscess and the antibiotics were respectively sufficient to control the collection and to obtain a favorable outcome. The treatment of comorbidity is crucial, which in our study necessitated insulin therapy within intensive care unit support in the case of the diabetic patient.

5. CONCLUSION

Retropharyngeal abscess are rare in adults and constitute a serious emergency. The diagnosis is based on the clinical and radiological pictures, and comorbidities should be appreciated. The management of these situations is based on antibiotics and surgical drainage.

References

- 1.Ngan JH, Fok PJ, Lai EC, Branicki FJ, Wong J. A prospective study on fish bone ingestion: experience of 358 patients. Annals of Surgery. 1990;211(4):459–462. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199004000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arora S, Sharma JK, Pippal SK, Yadav A, Najmi M, Singhal D. Retropharyngeal abscess following a gun shot injury. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology. 2009;75(6):p. 909. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30559-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marques PM, Spratley JE, Leal LM, Cardoso E, Santos M. Parapharyngeal abscess in children: five year retrospective study. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology. 2009;75(6):826–830. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30544-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acevedo JL, Shah RK. Retropharyngeal Abscess. eMedicine Specialties, Pediatrics: Surgery, Otolaryngology, 2009.

- 5.Lafitte F, Martin-Duverneuil N, Brunet E, et al. Rhinopharynx et espaces profonds de la face : anatomie et applications a la pathologie. Journal of Neuroradiology. 1997;24(2):98–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato K, Izumi T, Toshima M, et al. Retropharyngeal abscess due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a case of acute myeloid leukemia. Internal Medicine. 2005;44(4):346–349. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzon FS, Martin AD. Medical and surgical treatment of peritonsillar, retropharyngeal, and parapharyngeal abscesses. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2006;8(3):196–202. doi: 10.1007/s11908-006-0059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ridder GJ, Technau-Ihling K, Sander A, Boedeker CC. Spectrum and management of deep neck space infections: an 8-year experience of 234 cases. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 2005;133(5):709–714. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh I, Meher R, Agarwal S, Raj A. Carotid artery erosion in a 4-year child. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2003;67(9):995–998. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(03)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollard BA, El-Beheiry H. Pott’s disease with unstable cervical spine, retropharyngeal cold abscess and progressive airway obstruction. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. 1999;46(8):772–775. doi: 10.1007/BF03013913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato K, Izumi T, Toshima M, et al. Retropharyngeal abscess due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a case of acute myeloid leukemia. Internal Medicine. 2005;44(4):346–349. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatrath P, Black M, Blaney S. Subclinical presentation of massive retropharyngeal abscess. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2001;94(1):36–37. doi: 10.1177/014107680109400113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunawardana SS, Earley AR, Pollard AJ, Bethell D. Twelfth nerve palsy due to a retropharyngeal tuberculous abscess. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2004;89(6):p. 579. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.033639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lübben B, Tombach B, Rudack C. Tubercular spondylitis with retropharyngeal abscess. HNO. 2004;52(9):820–823. doi: 10.1007/s00106-003-0953-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Büyükbebeci O, Karakurum G, Daglar B, Maralcan G, Güner S, Güleç A. Tuberculous spondylitis: abscess drainage after failure of anti-tuberculous therapy. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. 2006;72(3):337–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamath MP, Bhojwani KM, Kamath SU, Mahabala C, Agarwal S. Tuberculous retropharyngeal abscess. Ear, Nose and Throat Journal. 2007;86(4):236–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang LF, Kuo WR, Tsai SM, Huang KJ. Characterizations of life-threatening deep cervical space infections: a review of one hundred ninety-six cases. American Journal of Otolaryngology. 2003;24(2):111–117. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2003.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]