Abstract

Double hydrophilic copolymers (PEG-b-PCDs) with one PEG block and another block containing β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) units were synthesized by macromolecular substitution reaction. Via a dialysis procedure, complex assemblies with a core-shell structure were prepared using PEG-b-PCDs in the presence of a hydrophobic homopolymer poly(β-benzyl L-aspartate) (PBLA). The hydrophobic PBLA resided preferably in the cores of assemblies, while the extending PEG chains acted as the outer shell. Host-guest interaction between β-CD and hydrophobic benzyl group was found to mediate the formation of the assemblies, where PEG-b-PCD and PBLA served as the host and guest macromolecules, respectively. The particle size of the assemblies could be modulated by the composition of the host PEG-b-PCD copolymer. The molecular weight of the guest polymer also had a significant effect on the size of the assemblies. The assemblies prepared from the host and guest polymer pair were stable during a long-term storage. These assemblies could also be successfully reconstituted after freeze-drying. The assemblies may therefore be used as novel nanocarriers for the delivery of hydrophobic drugs.

Keywords: Host-guest interactions, Self-assembly, β-Cyclodextrin, Core-shell nano-assemblies, Drug delivery

1. Introduction

Core-shell structured nanoparticles with different sizes, topologies, and material properties have been widely studied for applications in drug delivery, biomedical imaging, diagnostics, and biosensing [1–6]. These nanostructured systems can be constructed by polymers, nanocrystals, metals or their composites that possess distinctly different physicochemical characteristics. For nanoparticles with a core-shell architecture, multiple functionalities can be conveniently integrated to generate multi-functional nanoplatforms for better performances [1, 7]. Among these core-shell nanostructures, polymer systems are the most attractive for biomedical applications, mainly due to their synthetic flexibility, structural diversity, versatile modulability, and excellent biocompatibility [2, 3, 8–10].

Self-assembly of macromolecular amphiphiles has long been recognized as a powerful strategy to fabricate core-shell architectured nanostructures [11]. Nanoassemblies thus constructed have found applications in a variety of fields such as cosmetics, materials science, pharmaceutics, bioengineering, biomedicine, gene therapy, and tissue engineering. For instance, polymer micelles with a hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic shell have been intensively investigated for the delivery of lipophilic therapeutics, especially for cancer therapy [2, 3, 10, 12, 13]. Several nano-sized micellar formulations of antitumor drugs are already in clinical trials, and their efficacy has been demonstrated [14]. In addition, core-shell particles with a polyelectrolyte complex core that are assembled via electrostatic force have been of great interest for gene therapy [8, 15]. In these nanosystems, the core serves as nanocontainers for single/multiple therapeutics, imaging reagents or their combinations. The outer shell, however, can endow particles with colloidal stability and long circulation capability. Additional targeting units such as antibody and ligand can also be anchored onto the shell for selective delivery.

Until now, most of the polymeric core-shell assemblies are constructed via hydrophobic interactions, using amphiphilic copolymers with block, graft, comb, branch or dendritic architectures [16–23]. The driving forces for the assembling can also be other non-covalent forces such as electrostatic, hydrogen-bonding, stereocomplexation and charge transfer interactions [3]. Recently, cyclodextrin (CD) containing polymers have been widely used as building blocks to fabricate various networks and particulate assemblies, taking advantage of host-guest interactions [24, 25]. For example, supramolecular hydrogels and discrete nano- or microparticles can be constructed by the inclusion interactions between CD units and guest molecules [26–34]. One of our research foci has been on the development of core-shell structured nanoassemblies using β-CD containing polymers as macromolecular hosts [25]. β-CD conjugated polymers with a block or branch architecture were found to be able to assemble in the presence of guest molecules including small-molecule drugs and polymers with hydrophobic groups [35–38]. Through this protocol, we were able to fabricate thermosensitive nanosystems for temperature-triggered payload release using a thermosensitive guest poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm) [35], construct multifunctional assemblies for simultaneous drug and gene delivery using β-CD conjugated polyethyleneimine (PEI-CD) [37], and prepare chemical-responsive nanoassemblies for the delivery of lipophilic drugs [36]. The aim of this study was to systematically investigate the assembling behaviors of a β-CD containing hydrophilic-hydrophilic diblock copolymers (PEG-b-PCD) with poly(β-benzyl L-aspartate) (PBLA), and thoroughly examine the characteristics possessed by the assembled core-shell structures for potential drug delivery applications.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Material

L-Aspartic acid β-benzyl ester was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, USA). Triphosgene was obtained from Fisher (USA). β-Benzyl-L-aspartate N-carboxyanhydride (BLA-NCA) was synthesized according to the literature [39]. α-Methoxy-ω-amino-polyethylene glycol (MPEG-NH2) with an average molecular weight (MW) of 5000 was purchased from Laysan Bio, Inc. (Alabama, USA), and used without further purification. Ethylenediamine (EDA) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, USA) and distilled over CaH2 under reduced pressure. Coumarin 102 (C102), pyrene (≥99%), β-cyclodextrin (β-CD, ≥98%), and 1,6-Diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, USA) and used as received. The method established by Baussanne et al. was employed to synthesize 6-monotosyl β-CD [40].

2.2. Synthesis of PEG-b-PCD

PEG-b-polyaspartamide containing EDA units (PEG-b-PEDA) was firstly synthesized using MPEG-NH2 according to the previously reported method [41]. PEG-b-PCD copolymers were then synthesized using a slightly modified method established in our previous study [38]. Briefly, lyophilized PEG-b-PEDA (600 mg) and 5-fold excess amount of 6-monotosyl β-CD were reacted in 30 ml anhydrous DMSO at 60°C. This reaction was traced by 1H NMR and FTIR measurements. At the predetermined time points, a certain amount of the reaction mixture was collected and dialyzed against 0.1 N NaOH for 2 days to remove unreacted 6-monotosyl β-CD, and then dialyzed against distilled water for another 2 days. After being filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter, the resultant aqueous solutions were lyophilized. The optimized reaction conditions were employed to synthesize copolymers used in the following studies (Table 1). For the synthesis of PEG-b-PCD-1, PEG-b-PEDA with the degree of polymerization (DP) of 5 for PEDA block was reacted with 5 molar excess of 6-monotosyl β-CD in anhydrous DMSO at 60°C for 7 days. Purification was performed following the aforementioned procedures. In the case of PEG-b-PCD-2 and PEG-b-PCD-3, PEG-b-PEDA copolymers with DP of 10 and 15 were used, respectively. The same purification procedure as that for PEG-b-PCD-1 was followed.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the polymers employed in this study.

| Polymer | Mn | DP of the second blocka |

|---|---|---|

| PEG-b-PCD-1 | 11000a | 4 |

| PEG-b-PCD-2 | 15000a | 7 |

| PEG-b-PCD-3 | 24000a | 14 |

| PBLA | 2200b | — |

| HMw-PBLA | 20000b | — |

Calculated based on 1H NMR spectra;

Molecular weight calculated based on MALDI-TOF results.

2.3. Synthesis of poly(β-benzyl L-aspartate) (PBLA)

PBLA was synthesized according to a previously described technique [42]. Briefly, 1.5 g BLA-NCA was dissolved in 30 ml anhydrous dioxane, into which an appropriate amount of n-hexylamine was added to achieve a molar ratio of monomer to initiator of 20:1. Polymerization was performed at room temperature (22°C) for 5 days. After being precipitated from the diethyl ether, the polymer was dissolved in dichloromethane and was again precipitated from the diethyl ether. The resultant powder was dried under vacuum. The number-average molecular weight was determined by a matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometer to be about 2000.

2.4. Preparation of host-guest assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD and PBLA

Assemblies based on PEG-b-PCDs and PBLA were prepared by a dialysis procedure. In brief, PEG-b-PCD and PBLA were dissolved separately in DMSO at 50°C. A mixture solution with the appropriate weight ratio of PBLA/PEG-b-PCD was then dialyzed against deionized water for one day. Further characterization was performed after the dialysis solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter. For the preparation of C102 containing assemblies, after C102, PBLA, and PEG-b-PCD-3 were dissolved into DMSO, a similar dialysis procedure was adopted.

2.5. Characterization of polymers and assemblies

1H, 1H-1H Noesy, and 1H-1H Roesy spectra were recorded on a Varian INOVA-400 spectrometer operating at 400 MHz. The MALDI-TOF measurements were performed using a Waters Micromass TofSpec-2E operated in linear mode. Dithranol (purchased from Aldrich Chemical) was used as a matrix. The dried-droplet method was employed for sample preparation. Using pyrene as a fluorophore, the steady-state fluorescence spectra were measured on a JASCO FP-6200 fluorescence spectrophotometer with a slit width of 5 nm for both excitation and emission. All spectra were acquired from air-equilibrated solutions. For the fluorescence emission spectra, the excitation wavelength was set at 339 nm, while for the excitation spectra, the emission wavelength was 390 nm. The scanning rate was set at 125 nm/min. All tests were carried out at 25°C. Sample solutions were prepared as described previously [43]. In brief, the aqueous solutions of copolymers or assemblies containing pyrene (6.0×10−7 M) were incubated at 50°C for 12 h and subsequently allowed to cool overnight to room temperature.

The fluorescence anisotropy (r) was determined using a Fluoromax-2 fluorimeter equipped with an auto-polarizer accessory. The monochromator slits were set at 5 nm, and DPH was used as the fluorescence probe. The excitation wavelength was 360 nm, while the emission wavelength was 430 nm. The fluorescence anisotropy was calculated according to the relationship r = (IVV−GIVH)/(IVV+2GIVH), where G = IVH/IHH is an instrumental correction factor and IVV, IVH, IHV, and IHH refer to the resultant emission intensities polarized in the vertical or horizontal detection planes (second subindex) upon excitation with either vertically or horizontally polarized light (first subindex) [44]. To prepare sample solutions, a known amount of DPH in methanol was added to several 10 ml volumetric flasks and the methanol was evaporated at 40°C. To each flask a stock sample solution was added and heated at 50°C for 12 h and then cooled overnight to room temperature. The DPH concentration was kept at 1.0×10−6 M.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurement was performed on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument at 25°C. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) observation was completed using a NanoScope IIIa-Phase atomic force microscope connected to a NanoScope IIIa Controller with an EV scanner. Samples were prepared by drop-casting the dilute solution onto freshly cleaved mica. All the images were acquired under a tapping mode. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation was carried out on a JEOL-3011 high-resolution electron microscope operating at 300 kV. Samples were prepared at 25°C by dipping the grid into the aqueous solution of assemblies, and extra solution was blotted with a filter paper. After the water was evaporated at room temperature, samples were observed directly without any staining. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were taken on a field emission scanning electron microscope (XL30 FEG, Phillips) after a gold layer was coated using a sputter coater (Desk-II, Denton vacuum Inc., Moorstown, NJ) for 80 s. Samples were prepared by coating the aqueous solution of assemblies onto a freshly cleaved mica. Water was evaporated at room temperature under normal pressure.

2.6. Study on the stability of nanoassemblies

Both the long-term storage and freeze-drying stability was examined for PBLA/PEG-b-PCD nanoassemblies. For the long-term storage stability study, after dialysis and subsequent filtration an aqueous solution of assemblies was kept at room temperature, and average particle size was measured by DLS at various time points. To evaluate the effect of freeze-drying process on the stability of assemblies, an aqueous solution of assemblies was lyophilized and the obtained powder was reconstituted in water. Both DLS measurement and TEM observation was then performed before freeze-drying and after reconstitution.

2.7. In vitro release study

Lyophilized assemblies containing C102 were dispersed into deionized water (10 mg/ml). Then, 0.5 ml sample solution was placed into dialysis tubing, which was immersed in 30 ml 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4). At predetermined time intervals, 4 ml release medium was withdrawn, and fresh PBS was added. The concentration of C102 in the release buffer was determined by UV at 310 nm.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Polymer synthesis

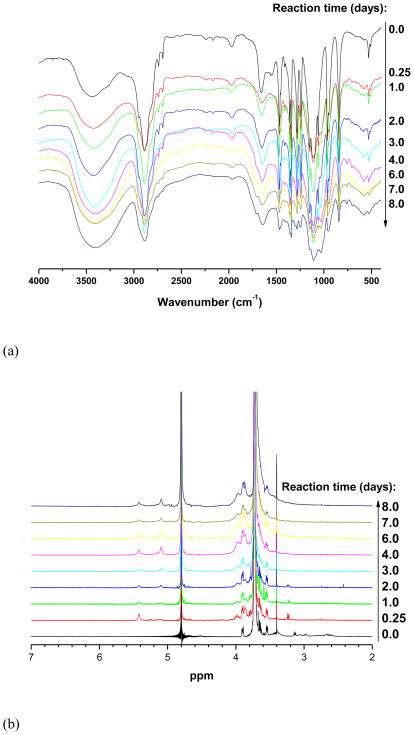

PEG-b-PCD copolymers were synthesized following the routes illustrated in Scheme S1. MPEG-NH2 with Mw of 5000 was used as a macromolecular initiator. The DP of PBLA was calculated from the 1H NMR spectroscopy based on the peak intensity ratio of benzyl protons on PBLA side chains (7.3 ppm) to the methylene protons of the PEG block (3.6 ppm). PEG-b-PBLAs with various PBLA lengths were obtained by varying the molar ratio of PEG to BLA-NCA. Fig. 1a shows the FTIR spectra of reaction products of PEG-b-PDEA and 6-monotosyl β-CD at various time points. As can be seen, a significant absorption peak at 1029 cm−1 appeared after CD conjugation. In addition, this peak increased significantly as more β-CD molecules were conjugated with reaction time. Consistent with FTIR results, the proton signals corresponding to β-CD were intensified when the reaction time increased as shown by 1H NMR spectra in Fig. 1b. This time dependent conjugation is illustrated in Fig 1c. These results indicated that β-CD molecules can be successfully introduced onto the side chain of PEDA block. The optimized reaction time is about 7 days for the conjugation reaction performed at 60°C. This reaction condition was adopted to synthesize the PEG-b-PCD copolymers mentioned in the following studies. The resultant copolymers can be easily dissolved in water at room temperature. The number-average molecular weight of polymers was calculated based on 1H NMR as well as MALDI-TOF measurements. The physicochemical properties of the polymers are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

(a) FI-IR and (b) 1H NMR spectra of reaction products of PEG-b-PEDA and 6-monotosyl β-CD/β-CD at various time points. (c) The time-dependent molar ratios of β-CD unit to ethylene group of PEG block, which were calculated based on 1H NMR spectra shown in (b). PEG-b-PEDA with a DP of 18 for PDEA block was employed in this study, and the reaction was performed at 60°C.

3.2. Assemblies based on PEG-b-PCDs and PBLA

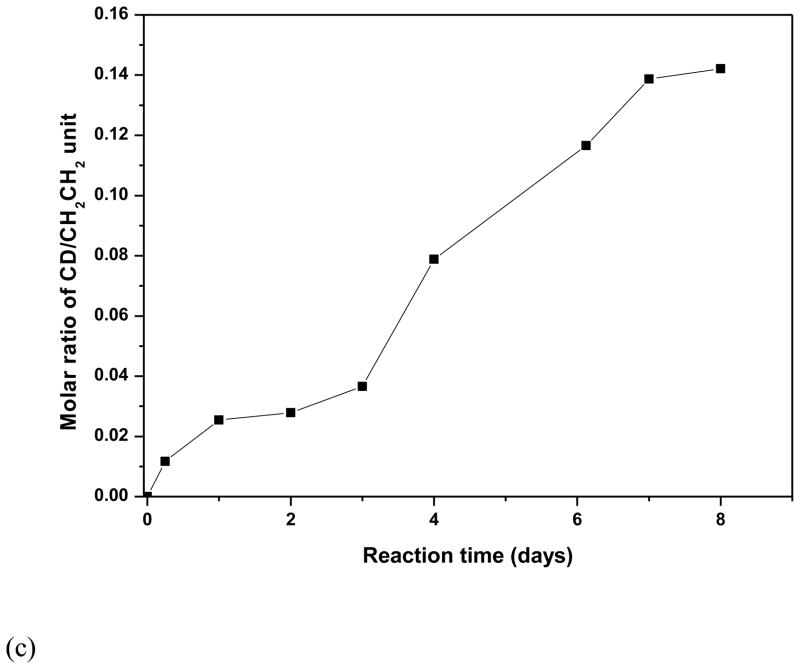

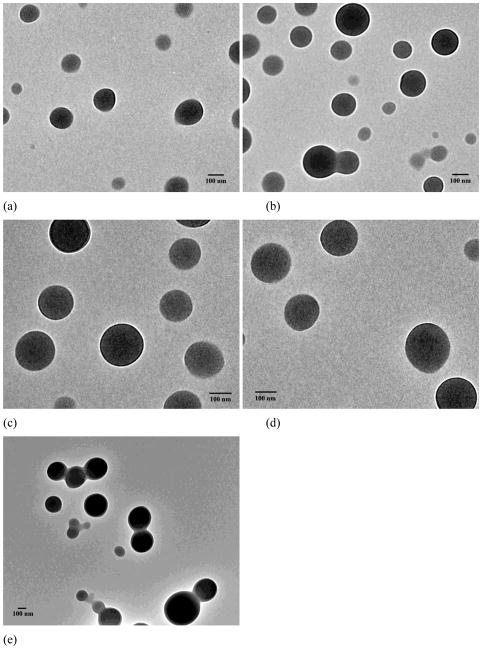

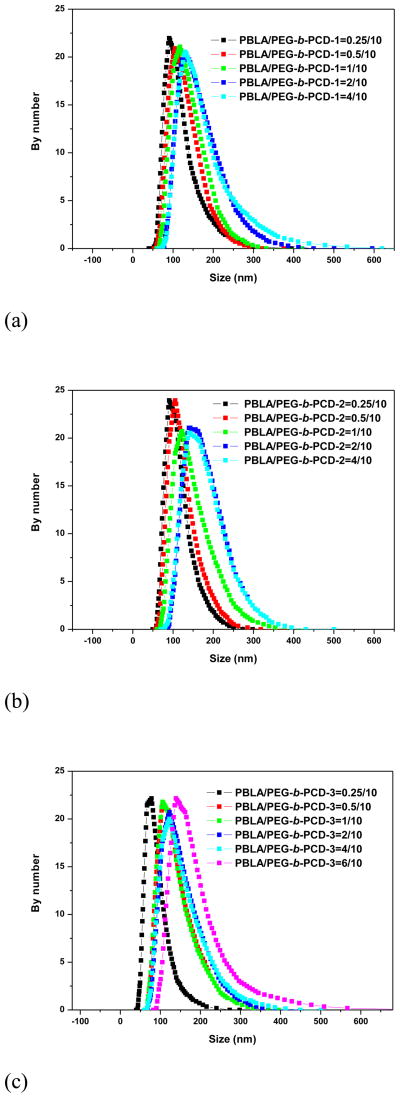

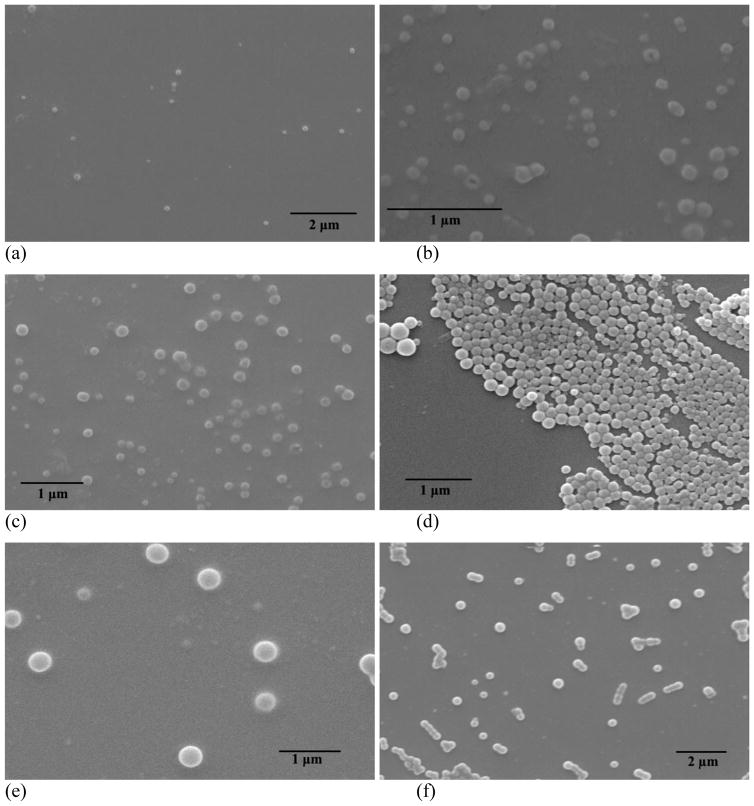

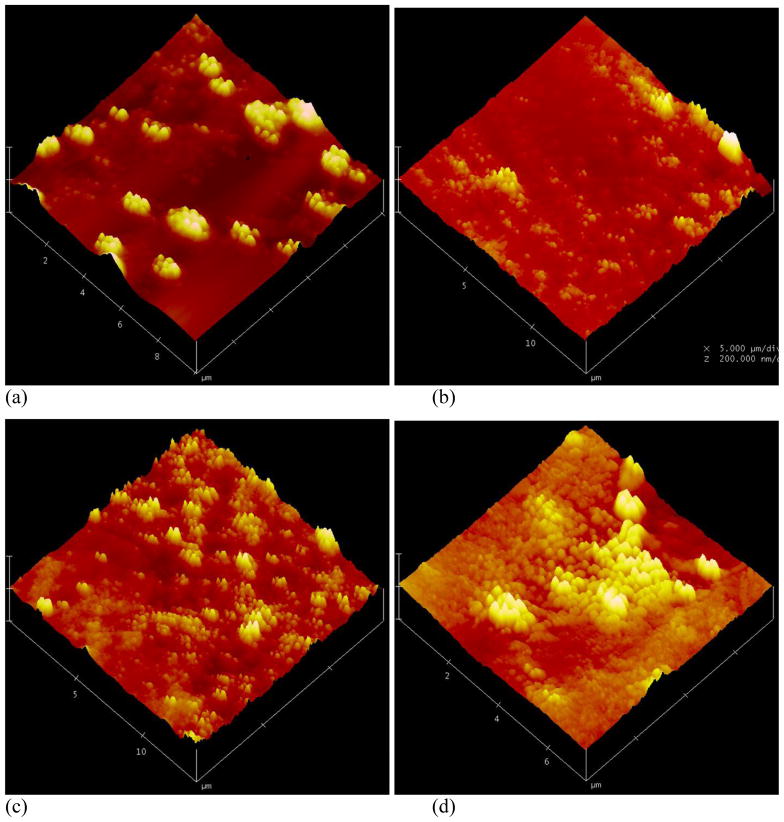

The dialysis method was employed to prepare assemblies based on PEG-b-PCDs and hydrophobic PBLA. The assemblies were primarily characterized using TEM, SEM, AFM and DLS. Fig. 2 shows TEM images of assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD-1 and PBLA. Independent of the PBLA content, spherical assemblies were observed. Particle size distribution measured using DLS is presented in Fig. 3. The mean size was increased as the PBLA content increased. It leveled off when the PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-1 ratio reached 4/10 (Fig. 3a). The average size by number was 110, 121, 131, 158, and 160 nm for assemblies derived from formulations with polymer ratio of 0.25/10, 0.5/10, 1/10, 2/10, and 4/10, respectively. Similarly, the average size determined by the DLS was 107, 118, 139, 172, and 169 nm for assemblies with the PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-2 ratio of 0.25/10, 0.5/10, 1/10, 2/10, and 4/10, respectively (Fig. 3b). The mean particle size was 85, 131, 130, 142, 143, 173 nm for assemblies with the PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-3 ratio of 0.25/10, 0.5/10, 1/10, 2/10, 4/10 and 6/10, respectively (Fig. 3c). Similar to PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-1 assemblies, the PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-2 and PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-3 assemblies were also spherical in morphology (Fig. S1&S2). For assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD-3 and PBLA, the morphology was further examined using SEM. As shown in Fig. 4, nanoparticles with well-defined spherical topology could be observed irrespective of the polymer feed ratio of PBLA to PEG-b-PCD-3. Additionally, selected AFM images presented in Fig. 5 also indicated that these assemblies have a nearly spherical morphology. In contrast to the TEM, SEM and AFM can provide three-dimensional information in terms of particle morphology. Accordingly, the combination of TEM, SEM, and AFM results points to the conclusion that spherical nanoparticles are assembled by PEG-b-PCD and PBLA.

Fig. 2.

TEM images of assemblies based on formulations with various ratios of PBLA to PEG-b-PCD-1: (a) 0.25/10; (b) 0.5/10; (c) 1/10; (d) 2/10; and (e) 4/10.

Fig. 3.

Particle size distribution of assemblies based on PEG-b-PCDs and PBLA of various weight ratios: (a) PEG-b-PCD-1, (b)PEG-b-PCD-2, and (c) PEG-b-PCD-3.

Fig. 4.

SEM images of assemblies based on formulations with various ratios of PBLA to PEG-b-PCD-3: (a) 0.25/10; (b) 0.5/10; (c) 1/10; (d) 2/10; (e) 4/10; and (f) 6/10.

Fig. 5.

Typical AFM images of assemblies constructed by PBLA and PEG-b-PCD-3 of various weight ratios: (a) 1/10, (b) 2/10, (c) 4/10, and (d) 6/10.

A simple calculation suggested that the number of benzyl groups in PBLA was excessive compared with that of β-CD units in PEG-b-PCD copolymers. This is true even for the formulations with the lowest PBLA content. Accordingly, some benzyl groups did not interact with β-CD, which can provide hydrophobic components to incorporate lipophilic compounds. This is similar to polymer micelles with hydrophobic cores. In the case of formulations with relatively high PBLA contents, the PBLA is in excess and there should be some free PBLA chains that have not complexed with β-CD units. As a result, those free chains may be encapsulated into the cores of the resultant assemblies by the hydrophobic interaction. The higher the quantity of PBLA, the more PBLA chains will be incorporated in the cores, which in turn leads to the increased particle size of obtained assemblies.

The fluorescence technique was then employed to provide information of the cores of the assemblies, and pyrene was used as a probe. Fig. S3 shows both the excitation and emission spectra of pyrene in the presence of PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-3 assemblies and PEG-b-PCD-3 itself. As a control, an aqueous solution of micelles based on PEG-b-poly(β-benzyl L-aspartate) (PEG-b-PBLA) was also employed. In the case of PEG-b-PCD-3, the (0, 0) band in the excitation spectrum had a peak at 335 nm. A slight red-shift effect was found on the assemblies prepared based on the formulations with PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-3 ratios of 0.25/10, 0.5/10, and 1/10, and the maximal peak was at 336 nm. More significant red-shift was observed for assemblies with PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-3 ratios of 2/10, 4/10 and 6/10, and the maximal excitation band moved to 341 nm (Fig. S3a). This value was even larger than that for the aqueous solution of PEG-b-PBLA micelles (339 nm). Similar results were observed for assemblies derived from PBLA and PEG-b-PCD-1 or PEG-b-PCD-2. Pyrene in an aqueous environment has a characteristic (0, 0) band at 333 nm, and this band shifts to 338 nm in a hydrophobic environment [45]. The red shift of (0, 0) band in the excitation spectrum of pyrene is a sign of decrease in polarity of its microenvironment [43, 45]. The intensity ratio of I338/I333, which serves as a measure of environmental hydrophobicity, was calculated and the data are listed in Table 2. It was observed that the magnitude of I338/I333 increased as the PBLA loading increased regardless of the composition of PEG-b-PCD copolymer. For assemblies based on PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-3 with relatively high PBLA contents, the values of I338/I333 were closer to that of PEG-b-PBLA micelles. As for the emission spectra, all samples exhibited a strong excimer bond at ~475 nm (Fig. S3b). However, compared with that of PEG-b-PCD-3 and PEG-b-PBLA micelles, the intensity ratio of excimer (at 475 nm) to monomer (at 373 nm), i.e., IE/IM of assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD-3/PBLA was significantly larger as presented in Table 2. In addition, a calculation of the intensity ratio between the third and first highest energy emission peaks, known as the I3/I1 ratio, has been shown to correlate well with the solvent polarity, also suggests that assemblies of PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-3 exhibited more hydrophobic microdomains compared with that of PEG-b-PCD alone or even PEG-b-PBLA micelles (Table 2). Accordingly, these results suggest that assemblies based on PBLA/PEG-b-PCD possessed cores similar to that of PEG-b-PBLA micelles. In other words, the hydrophobic PBLA resided preferably in the cores of PBLA/PEG-b-PCD assemblies.

Table 2.

The effect of host/guest polymer ratios on the characteristics of assemblies.

| Copolymer | Weight ratio of PBLA/PEG-b-PCD | Average particle size(nm) | I338/I333 | I3/I1 | IE/IM | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG-b-PCD-1 | 0.00:10 | — | 0.77 | 0.94 | 0.42 | 0.15 |

| 0.25:10 | 110 | 0.90 | 1.40 | 1.10 | 0.18 | |

| 0.5:10 | 121 | 0.96 | 1.50 | 1.24 | 0.18 | |

| 1:10 | 131 | 1.01 | 1.64 | 1.30 | 0.20 | |

| 2:10 | 158 | 1.06 | 1.70 | 1.31 | 0.22 | |

| 4:10 | 160 | 1.17 | 1.73 | 1.40 | 0.25 | |

| PEG-b-PCD-2 | 0.00:10 | — | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.56 | 0.15 |

| 0.25:10 | 107 | 0.93 | 1.10 | 1.31 | 0.19 | |

| 0.5:10 | 118 | 1.05 | 1.21 | 1.44 | 0.18 | |

| 1:10 | 139 | 1.19 | 1.28 | 1.47 | 0.21 | |

| 2:10 | 172 | 1.35 | 1.44 | 1.37 | 0.23 | |

| 4:10 | 169 | 1.25 | 1.51 | 1.29 | 0.27 | |

| PEG-b-PCD-3 | 0.00:10 | — | 0.80 | 1.12 | 1.22 | 0.17 |

| 0.25:10 | 85 | 1.02 | 1.24 | 2.58 | 0.18 | |

| 0.5:10 | 131 | 1.04 | 1.21 | 2.53 | 0.19 | |

| 1:10 | 130 | 1.05 | 1.19 | 2.48 | 0.23 | |

| 2:10 | 142 | 1.36 | 1.35 | 2.45 | 0.22 | |

| 4:10 | 143 | 1.29 | 1.49 | 2.42 | 0.24 | |

| 6:10 | 173 | 1.37 | 1.32 | 2.37 | 0.28 | |

| PEG-b-PBLA | — | — | 1.46 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.25 |

Further information on the microviscosity of the inner cores of assemblies was provided by 1H NMR and fluorescence anisotropy. For the NMR characterization, PBLA/PEG-b-PCD assemblies were prepared by dialysis and the resultant aqueous solution was lyophilized. The dried sample was dissolved into D2O, and the 1H NMR spectrum was acquired. The same sample was subjected to the NMR measurement after it was lyophilized and dissolved in DMSO-d6. As shown in Fig. S4a, no proton signals corresponding to PBLA can be observed for assemblies based on PBLA and PEG-b-PCD-3 in D2O. However, signals at 7.3 and 5.0 ppm that are characteristic peaks of protons related to benzyl groups, were evident in DMSO-d6. The same result was observed for assemblies based on PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-2 as shown in Fig. S4b. This indicates that the cores of these assemblies are mainly comprised of PBLA chains with limited mobility, and therefore they possess a rigid core [46]. This characteristic is similar to micelles based on PEG-b-PBLA. It has been reported that small broad peaks were discerned in the 1H NMR spectrum of PEG-b-PBLA in D2O [46], which might be attributed to the presence of free PEG-b-PBLA chains in the case of micellar solution. No signal from PBLA, however, was observed from our assemblies, indicating that all PBLA chains were present in the cores. On the other hand, due to the highly hydrophobic nature of PBLA chains, they all existed in an aggregated form in a water solution. In the case of the fluorescence depolarization study, we used DPH as a fluorophore since its usefulness as a microviscosity probe has been well documented. The anisotropy value (r) of a fluorescent probe is correlated with the viscosity of microenvironment where the probe molecules locate, and a higher value of r indicates a more viscous microdomain [44]. As listed in Table 2, the magnitude of r measured for DPH in the aqueous solutions of PBLA/PEG-b-PCDs based assemblies was increased gradually as the PBLA content increased, which was even larger than that of the PEG-b-PBLA micelles when the PBLA content increased to a certain value. This result again suggests that the cores of PBLA/PEG-b-PCDs assemblies are essentially rigid. The rigid cores can provide the assemblies with dynamic stability against dilution [47], which is very important for their potential applications such as drug delivery.

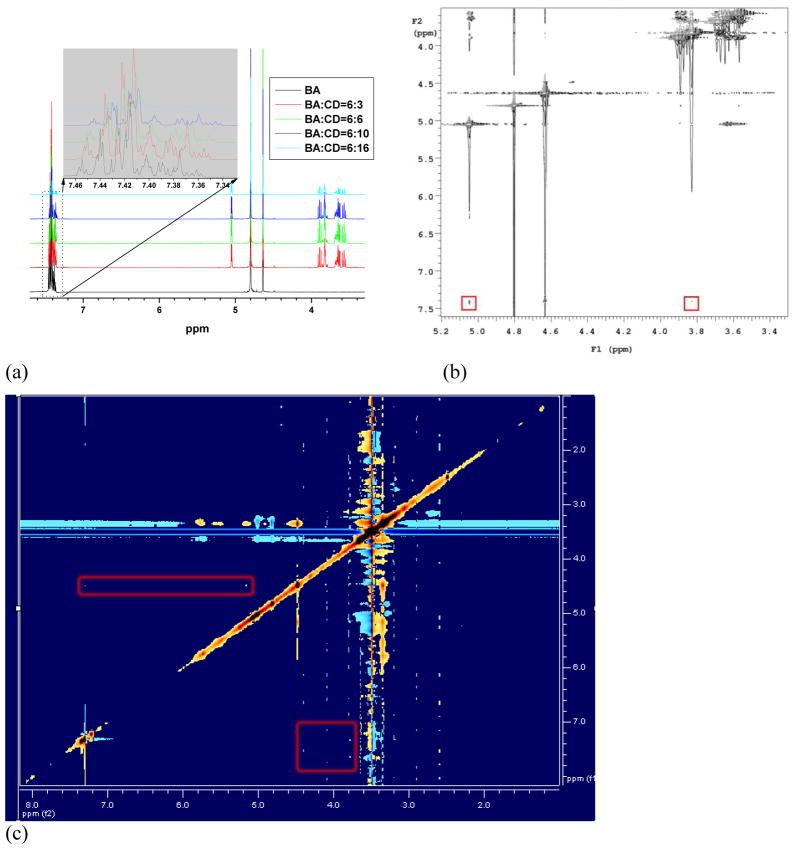

Based on above results, we can conclude that assemblies with spherical morphology can be successfully prepared using our newly synthesized PEG-b-PCDs and PBLA. The hydrophobic PBLA is the main component of the cores of these assemblies, while the extending PEG chains serve as the outer palisade. The particle size of this type of assemblies can be controlled by the weight content of PBLA. The host-guest interaction should be responsible for the formation of these assemblies, considering the inclusion of hydrophobic groups by β-CD. Initially, indirect evidence was provided by examining the interactions between β-CD and benzyl alcohol (BA). Fig. 6a shows the effect of β-CD content on the 1H NMR spectrum of BA. One can observe an up-field shift of chemical shift corresponding to the aromatic protons of benzyl group as the β-CD content is increased. This inclusion complexation-induced shift has been also reported previously [48]. In addition, correlation signals between BA and β-CD can be clearly observed from a 2D-Noesy spectrum illustrated in Fig. 6b. For instance, the aromatic protons at 7.4 ppm are correlated with the protons at 5.04 and 3.82 ppm that are H-1 and H-3 signals of β-CD, respectively. As well demonstrated, the signal shift of H-3 proton that locates in the interior cavity of β-CD, can be used as a measure of the host-guest complex formation [49]. These results suggest the presence of inclusion interactions between BA and β-CD. Furthermore, a direct proof was presented by a 2D-Roesy spectrum of PBLA and PEG-b-PCD-3 in DMSO. As shown in Fig. 6c, the presence of correlation signals of protons from β-CD units in PEG-b-PCD-3 and benzyl groups in PBLA suggests that the complexation between PBLA and PEG-b-PCD-3 can even occur in DMSO.

Fig. 6.

(a) 1H NMR spectra of benzyl alcohol (BA) in the presence of different contents of β-CD, the weight ratios of BA/CD are listed in the inset; (b) 2D-Noesy spectrum of the mixture of BA and β-CD with weight ratio of 6:16, the inset red rectangles indicate the correlation signals between the protons of BA and β-CD. All the spectra were acquired at room temperature using D2O as solvent. (c) 2D-Roesy spectrum of PBLA and PEG-b-PCD-3 in DMSO-d6. The data were acquired at 25°C after 15 mg PBLA and 50 mg PEG-b-PCD-3 were co-dissolved in 0.6 ml DMSO-d6.

Taken the above results together, the possible mechanism driving the formation of assemblies can be described as follows: The inclusion complexation of β-CD and benzyl group associate PBLA chains with PEG-b-PCD copolymer. The free benzyl groups from PBLA chains provide additional hydrophobic components that can further accommodate PBLA chains by hydrophobic interaction. As a result, the free PBLA molecules together with PBLA chains associated with the β-CD containing blocks form the cores of resultant nanoassemblies, while PEG chains act as a hydrophilic shell to stabilize the assemblies. This process is illustrated in Scheme S2.

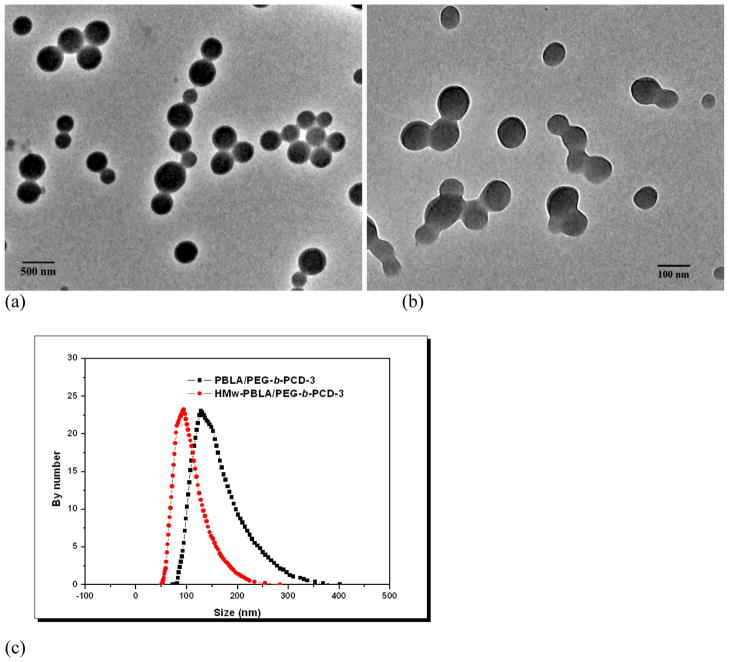

3.3. Effect of PBLA molecular weight on assemblies

To investigate the effect of PBLA molecular weight on assemblies, PBLA with a relatively high molecular weight (HMw-PBLA, Mn= 20 kDa) was also synthesized. Using the dialysis procedure, assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD-3 were prepared in the presence of PBLA or HMw-PBLA. As shown in Fig. 7a&b, whereas PBLA molecular weight did not affect the spherical morphology of the assemblies, it did affect the particle size. The number-averaged size of assemblies formulated with a PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-3 ratio of 1:5 was 152 nm, while that of assemblies based on HMw-PBLA/PEG-b-PCD of the same weight ratio was 102 nm (Fig. 7c). These results indicated that an increase in the molecular weight of a guest hydrophobic polymer led to a decrease in the particle size of the resultant assemblies, while it did not significantly affect the morphology of the assemblies. The number of polymer chains is smaller for HMw-PBLA than that for lower molecular weight PBLA at a constant PBLA/PEG-b-PCD weight ratio. Since not all PBLA chains were complexed with PEG-b-PCD, the free PBLA chains likely entered the cores of assemblies. Compared with the low molecular PBLA, likely a higher fraction of the HMw-PBLA was complexed. Consequently, there were fewer free HMw-PBLA chains available for the cores, leading to a smaller assembly size.

Fig. 7.

TEM images of assemblies based on PBLA and PEG-b-PCD-3 with different molecular weight (a-c); (a) PBLA, (b) HMw-PBLA, (c) size distribution curves obtained from DLS measurements. Both formulations had a PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-3 ratio of 1:5.

3.4. Effect of the long-term storage and freeze-drying on the size and morphology of the assemblies

For the assemblies to be used as drug delivery carriers, the stability during long-term storage and their dispersion behavior after the reconstitution from a freeze-dried formulation is an important issue [50]. Frequently, storage and a freeze-drying process may result in the formation of large aggregates, which in turn influences their therapeutic efficacy. As a preliminary stability study, the effect of a long-term storage and freeze-drying/reconstitution on the size and morphology of assemblies was evaluated. For the long-term storage stability study, the time dependent change in the average particle size was determined by DLS for the aqueous solution of assemblies that was kept at room temperature. As shown in Fig. S5, both the number and intensity-averaged sizes increased only slightly when the storage time increased. Since the number-averaged particle size is more sensitive to the number of assemblies (smaller assemblies), while the intensity-averaged size is more sensitive to assemblies with large particle sizes, these results suggest that these types of assemblies are relatively stable during a long-term storage.

To evaluate the effect of freeze-drying on the stability of assemblies, their size distribution and morphology were examined before lyophilization and after reconstitution in water. Fig. S6a&b show the TEM images of assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD-3 and PBLA or HMw-PBLA after the freeze-drying and reconstitution. Independent of the molecular weight of PBLA, spherical assemblies remained after the freeze-dried samples were reconstituted. The size distribution of assemblies shown in Fig. S6c revealed that the freeze-drying and the subsequent reconstitution only resulted in a slight increase in particle size. Before lyophilization the polydispersity index of assembly size based on PBLA and HMw-PBLA was 0.062 and 0.071, respectively. After the freeze-drying/reconstitution process, they increased slightly to 0.076 and 0.086, respectively. This result indicated that these assemblies dispersed well after freeze-drying/reconstitution.

3.5. In vitro release of a model drug

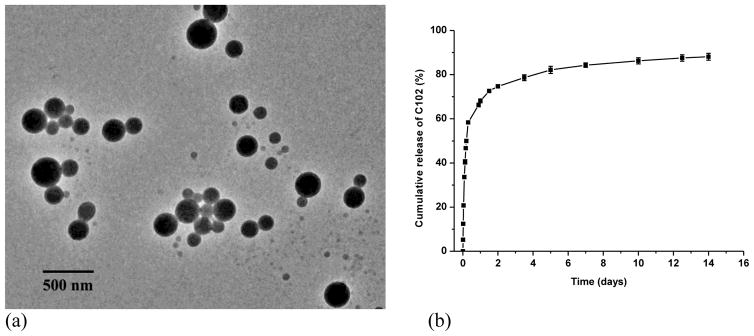

To substantiate the drug delivery application of assemblies based on PBLA and PEG-b-PCD, C102 was employed as a model drug. C102-containing assemblies were prepared by a similar dialysis procedure as described for blank assemblies. As illustrated in Fig. 8a, TEM image indicated that the encapsulation of C102 almost had no effect on the morphology of assemblies based on PBLA/PEG-b-PCD-3. This result suggests that the hydrophobic interaction between C102 and PBLA dominates over the complexation interaction between C102 and β-CD units in this case. As a result, C102 molecules were mainly incorporated into the hydrophobic cores composed of PBLA chains. In vitro release study was performed in 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4). As shown in Fig. 8b, a biphasic release profile can be observed, in which a rapid release stage is followed by a sustained release phase. The rapid phase is frequently observed for delivery systems with submicron size, such as polymeric micelles and nanoparticles [35, 36, 51]. Drug molecules located near the particular surface should be responsible for this burst release. On the other hand, drug molecules within the inner cores of assemblies dissociated and diffused out slowly, and therefore a sustained release stage was observed.

Fig. 8.

C102 containing assemblies based on PBLA and PEG-b-PCD-3 (weight ratio: 2:10): (a) TEM image, and (b) in vitro release profile in 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4). The loading content of C102 determined by UV measurement was 9.3 wt.%.

4. Conclusions

Di-hydrophilic copolymers (PEG-b-PCDs) with one PEG block and another block containing β-CD units were synthesized. By dialysis procedure, assemblies with a core-shell structure were prepared using PEG-b-PCD and a hydrophobic polymer PBLA. The cores of assemblies were mainly composed of PBLA chains, while the extending PEG chains were the main component of the shell. The host-guest interactions between β-CD and the hydrophobic benzyl group was found to be responsible for the formation of these types of assemblies, where PEG-b-PCD and PBLA serve as the host and guest macromolecules, respectively. The molecular weight of the guest polymer PBLA also displayed a significant effect on the size of the assemblies. The higher the molecular weight of PBLA, the smaller the particle size. The assemblies prepared from PEG-b-PCD and PBLA were stable during a long-term storage. In addition, these assemblies could be successfully reconstituted after freeze-drying. These assemblies may be employed as novel nanocarriers for the delivery of hydrophobic drugs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the research grants from the NIH (NIDCR DE015384 & DE017689). The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Prof. Kenichi Kuroda (University of Michigan) in fluorescence measurements and Prof. Nicholas A. Kotov (University of Michigan) in DLS measurements.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schartl W. Nanoscale. 2010;2:829–843. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00028k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaucher G, Marchessault RH, Leroux JC. J Control Release. 2010;143:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiradharma N, Zhang Y, Venkataraman S, Hedrick JL, Yang YY. Nano Today. 2009;4:302–317. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Reilly RK, Hawker CJ, Wooley KL. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:1068–1083. doi: 10.1039/b514858h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns A, Ow H, Wiesner U. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:1028–1042. doi: 10.1039/b600562b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu AH, Salabas EL, Schuth F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:1222–1244. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torchilin VP. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1532–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y, Kataoka K. Soft Matter. 2009;5:3810–3817. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kabanov AV, Gendelman HE. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:1054–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang WD, Yoon HJ. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:211–222. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klug A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1983;22:565–582. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh KT, Yin HQ, Lee ES, Bae YH. J Mater Chem. 2007;17:3987–4001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukyanov AN, Torchilin VP. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:1273–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumura Y. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:793–802. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakizawa Y, Kataoka K. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;52:203–222. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harada A, Kataoka K. Prog Polym Sci. 2006;31:949–982. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riess G. Prog Polym Sci. 2003;28:1107–1170. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadjichristidis N, Iatrou H, Pitsikalis M, Pispas S, Avgeropoulos A. Prog Polym Sci. 2005;30:725–782. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirao A, Hayashi M, Loykulnant S, Sugiyama K, Ryu SW, Haraguchi N, Matsuo A, Higashihara T. Prog Polym Sci. 2005;30:111–182. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schluter AD. Top Curr Chem. 2005;245:151–191. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang JX, Qiu LY, Li XD, Jin Y, Zhu KJ. Small. 2007;3:2081–2093. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim YB, Moon KS, Lee M. J Mater Chem. 2008;18:2909–2918. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mang JX, Li SH, Li XD, Li XH, Zhu KJ. Polymer. 2009;50:1778–1789. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Manakker F, Vermonden T, Van Nostrum CF, Hennink WE. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:3157–3175. doi: 10.1021/bm901065f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang JX, Ma PX. Nano Today. 2010;5:337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van de Manakker F, van de Pot M, vermonden T, van Nostrum CF, Hennink WE. Macromolecules. 2008;41:1766–1773. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L, Guo XH, Wang J, Liu P, Prud’homme RK, May BL, Lincoln SF. Macromolecules. 2008;41:8677–8681. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koopmans C, Ritter H. Macromolecules. 2008;41:7418–7422. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Zhao DY, Ma RJ, Xiong DA, An YL, Shi LQ. Polymer. 2009;50:855–859. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Jiang M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3703–3708. doi: 10.1021/ja056775v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Wang S, Su H, Chen KJ, Armijo AL, Lin WY, Wang Y, Sun J, Kamei KI, Czernin J, Radu CG, Tseng HR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:4344–4348. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu YL, Li J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:3842–3845. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian W, Fan XD, Kong J, Liu YY, Liu T, Huang Y. Polymer. 2010;51:2556–2564. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang CA, Wang X, Li HZ, Ding JL, Wang DY, Li J. Polymer. 2009;50:1378–1388. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang JX, Feng K, Cuddihy M, Kotov NA, Ma PX. Soft Matter. 2010;6:610–617. doi: 10.1039/c000898b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang JX, Ellsworth K, Ma PX. J Control Release. 2010;145:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang JX, Sun HL, Ma PX. ACS Nano. 2010;4:1049–1059. doi: 10.1021/nn901213a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang JX, Ma PX. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:964–968. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daly WH, Poch D. Tetrahedron lett. 1988;29:5859–5862. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baussanne I, Benito JM, Mellet CO, Fernández JMG, Law H, Defaye J. Chem Commun. 2000:1489–1490. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arnida Nishiyama N, Kanayama N, Jang WD, Yamasaki Y, Kataoka K. J Control Release. 2006;115:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blout ER, Karlson RH. J Am Chem Soc. 1956 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilhelm M, Zhao CL, Wang YC, Xu RL, Winnik MA, Mura JL, Riess G, Croucher MD. Macromolecules. 1991;24:1033–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ringsdorf H, Venzmer J, Winnik FM. Macromolecules. 1991;24:1678–1686. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Astafieve I, Zhong XF, Eisenberg A. Macromolecules. 1993;26:7339–7352. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwon G, Naito M, Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y, Kataoka K. Langmuir. 1993;9:945–949. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allen C, Maysinger D, Eisenberg A. Colloid Surf B-Biointerfaces. 1999;16:3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmitz S, Ritter H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:5658–5661. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rekharsky MV, Goldberg RN, Schwarz FP, Tewari YB, Ross PD, Yamashoji Y, Inoue Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8830–8840. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyata K, Kakizawa Y, Nishiyama N, Yamasaki Y, Watanabe T, Kohara M, Kataoka K. J Control Release. 2005;109:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakanishi T, Fukushima S, Okamoto K, Suzuki M, Matsumura Y, Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y, Kataoka K. J Control Release. 2001;74:295–302. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.