Abstract

As hybrid cochlear implant devices are increasingly used for restoring hearing in patients with residual hearing it is important to understand electrically evoked responses in cochleae having functional hair cells. To test the hypothesis that extracochlear electrical stimulation (EES) from sinusoidal current can provoke an auditory nerve response with normal frequency selectivity, the EES-evoked compound action potential (ECAP) was investigated in this study. Brief sinusoidal electrical currents, delivered via a round window electrode, were used to evoke ECAP. The ECAP waveform was observed to be the same as the acoustically evoked CAP (ACAP), except for a shorter latency. The input/output and intensity/latency functions of ACAPs and ECAPs were also similar. The maximum acoustic masking for both ACAP and ECAP occurred near probe frequencies. Since the masked tuning curve of a CAP reflects the frequency selectivity of neural excitation, these data demonstrate a highly specific activation of the auditory nerve, which would result in high degree of frequency selectivity. This frequency selectivity likely results from the cochlear traveling wave caused by electrically stimulated outer hair cells.

Keywords: Gerbil, Cochlea, Electrical stimulation, hearing, cochlear implant, cochlear compound action potential

INTRODUCTION

It has been found that extracochlear electrical stimulation (EES) by delivering current to the round window niche provokes otoacoustic emissions at the stimulated frequencies (Nuttall et al., 1995; Nuttall et al., 2001; Ren, 1996; Ren et al., 1995; Ren et al., 1998; Zou et al., 2003). In the gerbil, the transfer function of the extracochlear electrically evoked otoacoustic emission (EEOAE) shows a bandpass appearance ranging from a few kHz to above 30 kHz. Across all frequencies, the amplitude of the EEOAE has a positive linear relationship to the applied current levels. EES produced not only an EEOAE but also an acoustic-like traveling wave on the basilar membrane (BM) (Nuttall et al., 1995). These data indicate that OHCs located inside the electrical field generated by the applied current produce mechanical vibrations at the stimulated frequencies through their electrical-mechanical transduction. This electrically evoked mechanical energy propagates to the external ear canal to form the EEOAE and to its resonant place along the BM (Ren, 1996; Ren et al., 1996). Forward propagated energy at a resonant location should stimulate inner hair cells in a manner identical to an acoustically evoked traveling wave and cause auditory nerve excitation. Since the traveling wave mechanism works as a frequency analyzer in the cochlea (von Bekesy, 1970), a normal frequency selectivity is expected from this electrically evoked response. The aim of this study is to test whether EES with a brief sinusoidal electrical current can provoke an auditory nerve response with normal frequency selectivity. The cochlear compound action potential (CAP) and the masking tuning curve were used to measure auditory nerve excitation and its frequency selectivity.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animal preparation was similar to a method described previously (He et al., 2008; Ren, 2002; Ren, 2004; Ren et al., 1995). Experimental protocols were approved by Oregon Health Sciences University Committee on Use and Care of Animals. Eleven healthy young Mongolian gerbils weighing 55 to 90 g, were used in this study. Analgesia and tranquilization were provided by fentanyl (0.32 mg/kg i.p.) and pentobarbital sodium (30 mg/kg i.p.). Rectal temperature was maintained at 38±1°C with a servo-regulated heating blanket. A tracheotomy was performed and a ventilation tube was inserted into the trachea to ensure free breathing. The auditory bulla was opened through a ventral surgical approach and the middle ear muscles were cut. A Teflon-insulated 3-T platinum-iridium electrode with an uninsulated 200–300 µm diameter ball was placed in the round widow niche. Another platinum-iridium electrode was placed on the surface of the first cochlear turn. For CAP measurement, an Ag-AgCl ball electrode was placed in the round window niche, and another Ag-AgCl electrode in the muscle near the bulla was used as a ground electrode. A 1 ms sinusoidal signal with a 0.5 ms rise/fall time and alternated phase, was generated by a computer with a D/A converter. This electrical stimulus was delivered to the platinum-iridium electrodes through a battery-powered optically isolated stimulator. The current level was controlled by a programmable attenuator. After amplification with a gain of 1000, the round window signal was digitized over a 10 ms time window with an A/D converter and averaged 128 times. For comparison of ECAP and ACAP, an acoustic tone at the same frequency as the electrical stimulus was delivered to the external ear canal through an earphone. The earphone was coupled to a microphone (Etymotic Research ER-10B+, Elk Grove Village, IL) for monitoring the sound pressure in the ear canal. ECAP and ACAP at different frequencies and different stimulus levels were collected in 7 animals. To observe the forward masking responses of ECAP and ACAP, in 4 animals, a 10 ms acoustic tone burst at different frequencies was presented 10 ms before the onset of electrical or acoustical stimulus. The sound pressure levels of different masker frequencies, at which CAPs were suppressed from 10 µV to 1 µV, defined the masking tuning curves.

RESULTS

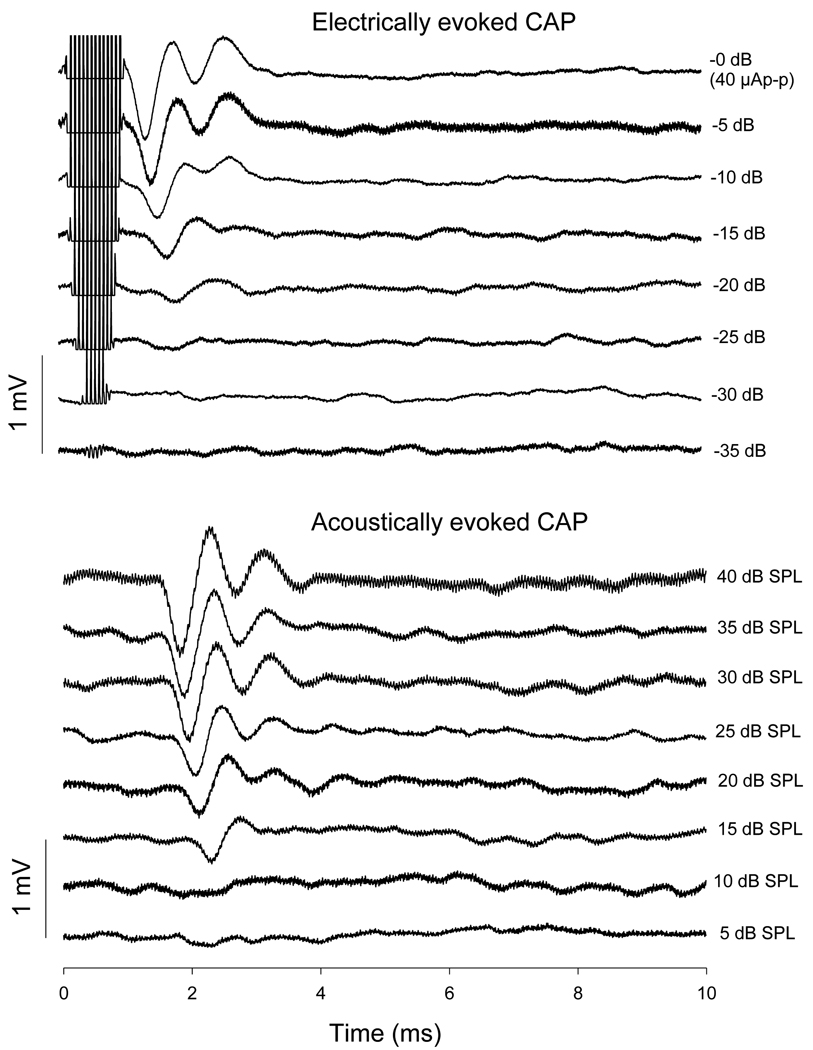

The ACAP thresholds at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24 kHz were below 25 dB SPL in all animals. ECAP thresholds were 2 to 10 µA p-p. Fig. 1 shows a series of CAP responses evoked by electrical and acoustic stimuli. The ECAP and ACAP data shown were both collected at the same frequency (16 kHz) for different levels of electrical and acoustic stimulation. The two dominant peaks of the typical CAP, N1 and N2, were clearly shown in the ECAP and ACAP responses. As the sound pressure or electrical current level was raised from low levels, N1 was the first to appear, followed by N2 at higher intensities. The N1 threshold was approximately 5–10 dB lower than the N2 threshold. For electrically evoked CAP, the first ms of the curves was dominated by electrical current-caused artifacts.

Fig. 1.

A series of CAP responses evoked by electrical and acoustic stimuli. Both of the ECAP and ACAP data are collected at 16 kHz and from the same guinea pig. As electrical or acoustic level was raised from low levels, N1 is the first to appear, followed by N2 at higher intensities. Except for the shorter latency, ECAP’s waveform is very similar to that of ACAP.

The latency of ECAP is significantly shorter than that of ACAP. The CAP latency was defined as the time delay from the onsets of electrical or acoustic stimulus in the electrode or the ear canal to the start of the CAP response. For convenience the latency of ECAP or ACAP was measured by the time difference between the onset of stimuli and the time when the negative N1 peak occurred. The latency of ECAP is shorter than that of ACAP across different stimulus levels. The difference between the ECAP and ACAP time delay at the comparable CAP level with the same N1 amplitude is approximately 0.5 ms. This time difference indicates the propagation time of the acoustic stimulus from the speaker to the cochlea through a 15 cm tube. The latencies also show dependence on the stimulus level for both ECAP and ACAP. With the decrease of stimulus level, the negative N1 peak clearly shifted to the right, showing that longer N1 latencies result from lower level stimuli.

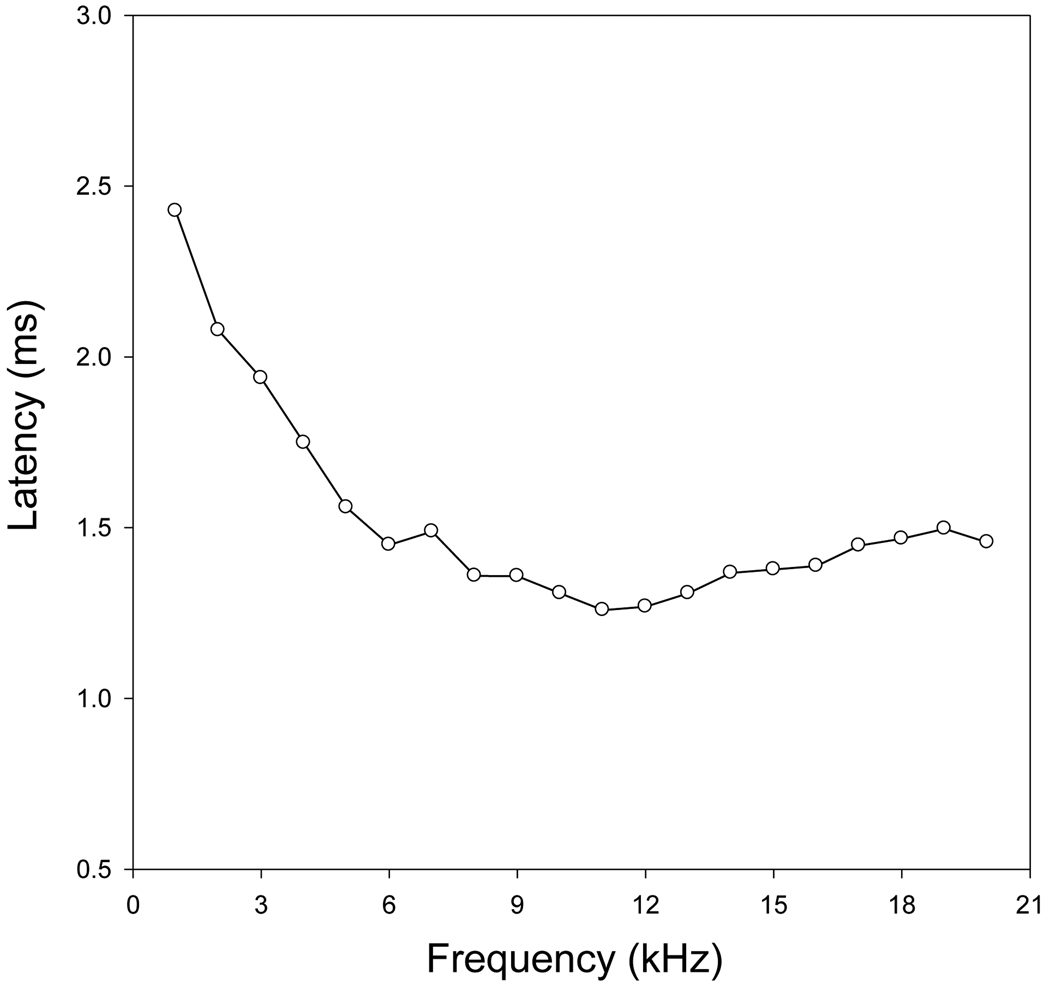

The frequency dependence of the latency of ECAP is presented in Fig. 2. The data in this figure were collected from the same ear as Fig. 1. Each ECAP curve was evoked by an electrical tone burst at different frequencies but with the same current level (40 µA p-p). As the stimulus frequency increased, the ECAP latency decreased rapidly from ~2.5 to 1.5 ms. The decrease rate became smaller at frequencies above 5 kHz. The latency of ECAP reached the minimum at ~12 kHz and then gradually increased slightly.

Fig. 2.

Frequency dependence of ECAP latency. The data was collected at the electrical current level of 40 µA p-p. The latency, time from the onset of stimuli to the N1 peak, was plotted as a function of frequency. The latency decreases with frequency and reaches the minimum around 12 kHz. Above 12 kHz, the latency increase slightly as frequency increases.

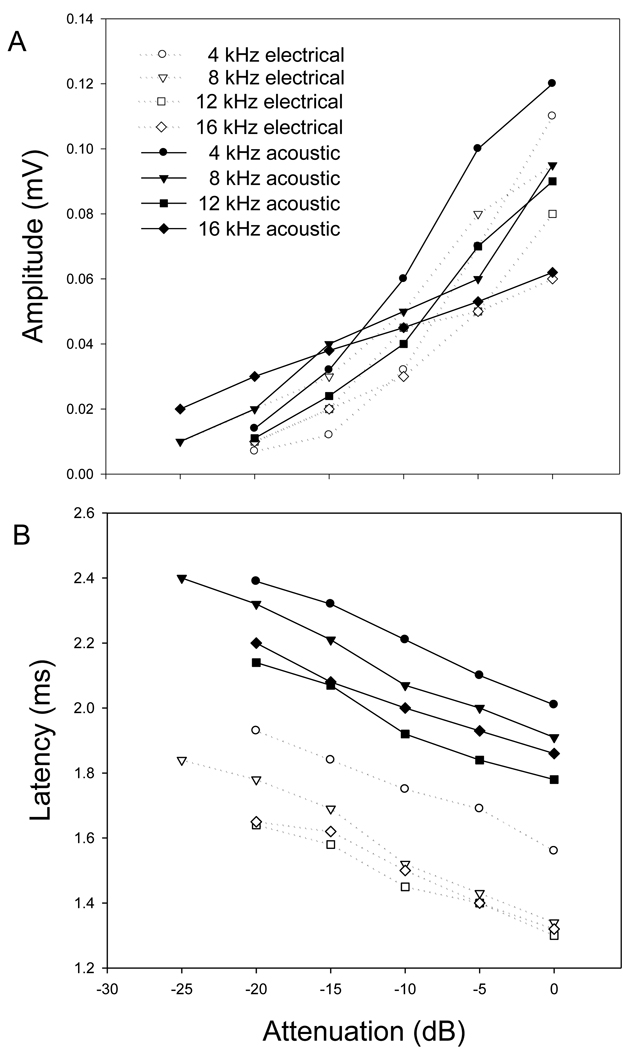

Fig. 3 A presents the input/output (I/O) function of the ECAP and ACAP at the frequencies of 4, 8, 12 and 16 kHz. For electrical stimuli, the stimulus levels are referred to 40 µA p-p. For acoustic stimuli, the stimulus levels are attenuated from the sound pressure level at which the ACAP amplitude is approximately equal to the ECAP evoked by 40 µA p-p current. This sound pressure level varied from 30 to 40 dB SPL at 4 to 16 kHz. A positive I/O function was found for both ECAP and ACAP across frequencies. Approximately, the ECAP I/O curves have the same slope as ACAP I/O curves.

Fig. 3.

(A) The input/output functions of ECAP are similar to ACAP input/output function. (B) A negative linear relationship between the latency and stimulus level in dB for both ECAP and ACAP.

Fig. 3 B presents the ECAP and ACAP stimulus level/latency function. The results presented in this figure were obtained from the same ear as the data in Fig. 3 A. However these data are representative of finings in the other subjects. For each curve, the data were collected at the same frequency with different electrical or acoustic stimulus levels. A negative linear relationship between the latency and stimulus level in dB was demonstrated for both ECAP and ACAP. As Fig. 1, Fig. 3 shows that ECAP latencies are consistently about 0.5 ms shorter than ACAP at comparable response amplitude at the same frequency.

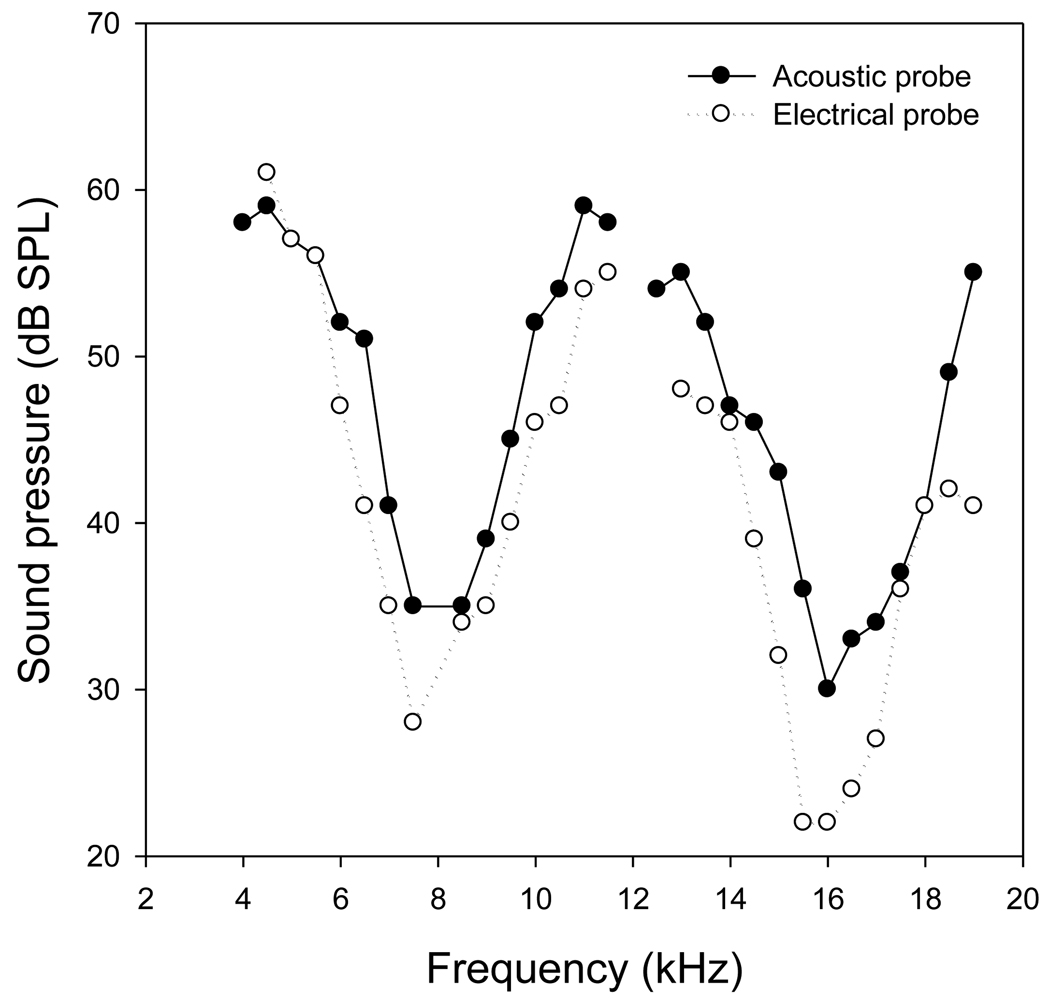

Acoustic forward masking turning curves for ECAP and ACAP are shown in Fig. 4. The abscissa indicates a linear scale of frequency in kHz, and the ordinate is a scale of sound pressure level (dB SPL) of acoustic maskers required for complete masking of ECAP or ACAP. The general shapes of the ECAP masking turning curves (solid line) are similar to those of the ACAP masking turning curves (dashed line). The negative peaks of ECAP and ACAP suppression turning curves are located at the same frequency location near the probe tone frequency. This indicates that the strongest suppression occurs at approximately the same frequency as the probe tone for both ECAP and ACAP.

Fig. 4.

ECAP masking turning curves (solid line) are similar to those of ACAP masking turning curves (dished line) with the same probe tone frequency. The negative peaks of ECAP and ACAP suppression turning curves are near the probe tone frequencies.

DISCUSSION

The electrophonic effect [5] has been intensively studied, since it was first experienced and described by Volta in 1800 (Jones et al., 1940; Stevens, 1936; Volta, 1800). Flottorp (Flottorp, 1976) studied of the electrophonic effect and concluded that the origin of the effective stimulus is acoustic energy generated by mechanical vibration at the interface between an electrode and the skin. From studies of the cochlear prosthesis, a contribution of electrophonic effect has been found in the electrically induced brainstem responses (Black et al., 1983a; Black et al., 1983b; Kiang et al., 1972; Lusted et al., 1988; van den Honert et al., 1984). McAnally et al. (McAnally et al., 1993) found that a sinusoidal electrical current could mask conventional CAPs, suggesting a spatial tuning of the hair cell mediated response along the cochlea. Kirk and Yates (Kirk et al., 1994) found that intracochlear electrically evoked CAPs could be masked by acoustic tones in guinea pig ears, indicating electrically evoked travelling waves in the cochlea. Like intracochlear electrical stimulation in the gerbil and guinea pig (Hubbard et al., 1982), extracochlear electrical stimulation produces an EEOAE in the gerbil (Ren et al., 1995). Direct measurement of the basilar membrane vibration demonstrated electrically evoked acoustic-like travelling waves at different frequencies of stimulation (Nuttall et al., 1995). Although the extracochlear electrically evoked auditory nerve response with normal frequency selectivity has been hypothesized, it has not been demonstrated experimentally.

The data presented in Fig. 1 demonstrate that electrical activity was provoked by 1 ms sinusoidal electrical current delivered to the round window niche. These responses occur after the electrical stimuli, with a time delay longer than 1 ms and their shape is identical to a conventional CAP. The latency of the electrically evoked response is longer than any electrically caused artifact and shorter than the latency of the acoustically evoked CAP at the same frequency and comparable levels. The latency of the electrically evoked response was frequency dependent, and could be masked by an acoustic tone at the same or near probe frequency. These characteristics indicate that the electrically evoked response is considered as an electrically evoked cochlear compound action potential (ECAP), dependent on evoked synchronized electrical activity of the auditory nerves. Similarities between ECAP and ACAP in the input/output function, latency/intensity function, especially the forward masking turning curves indicate that ECAP have an equal frequency selectivity as tone-evoked CAPs. Thus, this experiment demonstrates that the extracochlear electrical stimulation by a sinusoidal current causes auditory nerve response with a normal (acoustic-like) frequency selectivity in the normal gerbil cochlea. This frequency selectivity likely results from the cochlear traveling waves, which are caused by electrically stimulated outer hair cells. The current results may be of significance in future technology for prosthetic stimulation of the impaired ear, particularly those with significant residual functional hair cells and hearing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH-NIDCD and Guanghua Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Black RC, Clark GM, Tong YC, Patrick JF. Current distributions in cochlear stimulation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1983a;405:137–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1983.tb31626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RC, Clark GM, O'Leary SJ, Walters C. Intracochlear electrical stimulation of normal and deaf cats investigated using brainstem response audiometry. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1983b;399:5–17. doi: 10.3109/00016488309105588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flottorp G. Studies of the mechanisms of the electrophonic effect. Acta Otolaryngol. (Stockh) Suppl. 1976:341. [Google Scholar]

- He W, Fridberger A, Porsov E, Grosh K, Ren T. Reverse wave propagation in the cochlea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2729–2733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708103105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard AE, Mountain DC. Alternating current delivered into the scala media alters sound pressure at the eardrum. Science. 1982;222:510–512. doi: 10.1126/science.6623090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RC, Stevens SS, Lurie MH. Three mechanisms of hearing by electrical stimulation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1940;12:281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Kiang NYS, Moxon EC. Physiological considerations in artificial stimulation of the inner ear. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1972;81:1–17. doi: 10.1177/000348947208100513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk DL, Yates GK. Evidence for electrically evoked travelling waves in the guinea pig cochlea. Hear. Res. 1994;74:38–50. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusted HS, Simmons FB. Comparison of electrophonic and auditory-nerve electroneural responses. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1988;83:657–661. doi: 10.1121/1.396160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAnally KI, Clark GM, Syka J. Hair cell mediated responses of the auditory nerve to sinusoidal electrical stimulation of the cochlea in the cat. Hear. Res. 1993;67:55–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90232-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall AL, Ren T. Electromotile hearing: evidence from basilar membrane motion and otoacoustic emissions. Hear. Res. 1995;92:170–177. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall AL, Zheng J, Ren T, de Boer E. Electrically evoked otoacoustic emissions from apical and basal perilymphatic electrode positions in the guinea pig cochlea. Hear. Res. 2001;152:77–89. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T. Acoustic modulation of electrically evoked distortion product otoacoustic emissions in gerbil cochlea. Neurosci Lett. 1996;207:167–170. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T. Longitudinal pattern of basilar membrane vibration in the sensitive cochlea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:17101–17106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T. Reverse propagation of sound in the gerbil cochlea. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:333–334. doi: 10.1038/nn1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T, Nuttall AL. Extracochlear electrically evoked otoacoustic emissions: a model for in vivo assessment of outer hair cell electromotility. Hear. Res. 1995;92:178–183. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T, Nuttall AL. Acoustical modulation of electrically evoked otoacoustic emission in intact gerbil cochlea. Hear. Res. 1998;120:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T, Nuttall AL, Miller JM. Electrically evoked cubic distortion product otoacoustic emissions from gerbil cochlea. Hear. Res. 1996;102:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens SS. "On hearing by electrical stimulation.". J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1936;8:191–195. [Google Scholar]

- van den Honert C, Stypulkowski PH. Physiological properties of the electrically stimulated auditory nerve. II. Single fiber recordings. Hear. Res. 1984;14:225–243. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- volta A. On the electricity excited by mere contact of conducting substances of different kinds. Trans R Soc Phil. 1800;90:403–431. [Google Scholar]

- von Bekesy G. Travelling waves as frequency analysers in the cochlea. Nature. 1970;225:1207–1209. doi: 10.1038/2251207a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y, Zheng J, Nuttall AL, Ren T. The sources of electrically evoked otoacoustic emissions. Hear. Res. 2003;180:91–100. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]