Abstract

Job dissatisfaction among nurses contributes to costly labor disputes, turnover, and risk to patients. Examining survey data from 95,499 nurses, we found much higher job dissatisfaction and burnout among nurses who were directly caring for patients in hospitals and nursing homes than among nurses working in other jobs or settings, such as the pharmaceutical industry. Strikingly, nurses are particularly dissatisfied with their health benefits, which highlights the need for a benefits review to make nurses’ benefits more comparable to those of other white-collar employees. Patient satisfaction levels are lower in hospitals with more nurses who are dissatisfied or burned out—a finding that signals problems with quality of care. Improving nurses’ working conditions may improve both nurses’ and patients’ satisfaction as well as the quality of care.

More than a decade after the publication of To Err Is Human, the first Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on medical errors,1 patients remain concerned about the quality of care in hospitals. Patients’ satisfaction with care continues to leave much room for improvement. More than one-third of patients report that they would not recommend their hospital to family and friends, and the quality of nursing home care has been a concern to families for a long time.2,3

The passage of health reform legislation has stimulated an increased focus on patient-centered care and the importance of the patient experience. It is reasonable for patients to expect caregivers to be positively engaged in their work and for caregivers to be able to do their jobs efficiently and effectively in a supportive environment. However, this is not always the case.

Nurses have long reported that their work conditions are not conducive to providing patient-centered care that is safe and of high quality.4 The relationship between nurses’ working conditions and patient safety was recognized by the IOM report Keeping Patients Safe: Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses.5 Indeed, researchers have suggested that the work environment and staffing levels for nurses affect both nurse burnout—which is characterized by feeling extremely overextended and depleted of one’s emotional and physical resources in response to chronic job stressors—and job satisfaction, and are also associated with patients’ satisfaction with care.6–8

The goals of our study were threefold. First, we compared burnout, overall job satisfaction, and satisfaction with specific aspects of the job between nurses in different roles and settings (direct patient care roles in hospitals and nursing homes versus non–patient care roles and noninstitutional settings). Second, we evaluated whether the level of burnout and job satisfaction among those providing direct patient care in a hospital varied as a function of the environment in which the nurse works. Third, we estimated the effect of nurse burnout and job satisfaction on patient satisfaction with hospitals. To meet our goals, we combined data from three sources: a survey of nurses, a patient satisfaction survey, and data on the hospitals in which the nurses in our study worked and their patients were treated.

Our analysis of survey responses from more than 95,000 registered nurses provides a unique opportunity to gain insight into how nurses perceive their jobs, to identify possible opportunities to change negative perceptions where they exist, and to examine whether nurses’ perceptions of their jobs have consequences for patients.

Study Data And Methods

DATA

We used a complex data set for this study. The data sources included the Multi-State Nursing Care and Patient Safety survey,9,10 a four-state survey of nurses’ working conditions from 95,499 registered nurses; the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey,11 which is a national, standardized, publicly available database of patients’ hospital experiences in short-term, acute care hospitals; and the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals, which compiles hospital-specific data from nearly all US hospitals on a range of variables, including organizational structure, personnel, hospital facilities and services, and financial performance.

NURSES

For the Multi-State Nursing Care and Patient Safety survey, we used a two-stage sampling design to collect information from registered nurses in California, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Florida. Our sampling frame was the state licensure lists for 2006–07. We surveyed nurses by mail at their homes.

Nurses who worked in hospitals were asked to provide the name of their employer, which allowed us to aggregate responses by hospital for the analysis of nurses’ reports and patient satisfaction. The response rate was 36 percent. To test for sample bias, we conducted a random-sample survey of nonrespondents from Pennsylvania and California, received a response rate of 91 percent, and found no response bias pertinent to this report.12 Further details on the sampling approach have been described elsewhere,9 and are available in the Appendix.13

The survey included questions about the nurses’ employment status and, for working nurses, their setting, role, work environment, experience of burnout, and job satisfaction. As in other work,14 we assessed burnout in terms of emotional exhaustion, which is the depletion of one’s emotional and physical resources due to work stress as measured on the nine-item emotional exhaustion subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory.6 Burnout is common in human service occupations such as nursing, and it results in nurses’ distancing themselves emotionally and cognitively from their work.6 Nurses were classified as burned out if their score was higher than the published average (27 or higher) for workers in health professions.15,16

Overall we measured job satisfaction and nurses’ satisfaction with specific aspects of their jobs—including salaries, benefits, opportunities for advancement, work schedules, independence, and professional status—on a four-point scale from “very satisfied” to “very dissatisfied.” Satisfaction measures were dichotomized so that nurses who reported being either “very dissatisfied” or “a little dissatisfied” were characterized as “dissatisfied.”

HOSPITALS

In the analyses below, we first compared the reported satisfaction and burnout of nurses in hospital and nonhospital settings. We then investigated how hospital nurses’ satisfaction and burnout related to the reported satisfaction of patients in the same hospitals. We aggregated responses from individual nurses working in 614 adult, nonfederal, acute care hospitals to create hospital-level measures of job satisfaction, burnout, nurses’ patient workloads, and the nursing work environment. Hospitals were included if they were represented by at least fifteen direct care hospital staff nurses in our survey.17An average of forty-nine staff nurses responded from each of the 614 study hospitals.

Nurse staffing was measured by calculating the mean number of patients cared for by all registered staff nurses in each hospital on their last shift. Nurses who reported caring for at least one but no more than twenty patients on the last shift were included in the measure.

The nursing work environment was measured using the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index, an instrument recommended by the National Quality Forum as one of fifteen nurse-sensitive indicators of health care quality.18 The subscales of the work index include items related to nursing leadership capacity, nurses’ participation in hospital affairs, nursing standards for quality patient care, and nurse-physician relationships.

Nurses indicated their level of agreement on whether certain organizational features were present in their jobs. Hospitals with four subscales above the median were classified as “better,” hospitals with two or three subscales above the median were classified as “mixed,” and those with one or no subscales above the median were classified as “poor.”7 Additional hospital-level variables were obtained from our nurse survey and American Hospital Association annual survey data to serve as control variables in the predictive models (for more information, see the Appendix).13

PATIENTS

We used HCAHPS survey data from the October 2006–June 2007 reporting period (the first publicly available results) so that our patient satisfaction measures were reflective of the patient experience in hospitals at about the same time as nurses’ working conditions were assessed with the nurse survey and the American Hospital Association survey. The HCAHPS survey comprises twenty-seven items. The data are aggregated and risk-adjusted before release and are reported publicly as a set of ten measures.

For our analysis, we used two measures: the percentage of patients who gave the hospital a rating of 9 or 10 out of 10 (high), and the percentage of patients who would definitely recommend the hospital to friends and family.

DATA ANALYSIS

To address the study goals, we first examined nurses’ job satisfaction and burnout by setting, role, and number and percentage of nurses who reported being dissatisfied with aspects of their jobs. We defined setting as hospital; nursing home; or other setting such as public and community health, ambulatory care, and other noninstitutional environment. Roles were “direct patient care,” “no direct patient care,” and “nonnursing roles.” Nurse managers are an example of individuals who work as a nurse but not in direct care; examples of nonnursing roles are pharmaceutical or durable medical equipment sales positions.

We then specifically examined how hospital nurses’ burnout and satisfaction with selected aspects of their jobs varied according to the employing hospital’s work environment classification (better, mixed, or poor). Finally, we used ordinary least squares regression to estimate the effects on patient satisfaction of job satisfaction and burnout among hospital nurses providing direct patient care (see the Appendix).13 These hospital-level regression models included all 428 acute care hospitals in California, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania that both reported HCAHPS data to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and were represented by responses from at least fifteen direct care hospital staff nurses in our survey.17

LIMITATIONS

A primary limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design. A longitudinal approach would have allowed us to better establish a causal relationship between the variables of interest. The HCAHPS survey data analyzed here included only institutions that voluntarily participated in the first wave of surveys that were publicly reported. These hospitals were more likely than others to be large, nonprofit, teaching institutions in heavily populated areas. Therefore, these structural characteristics were included as controls in our fully adjusted models.

Since July 2007, reporting through the HCAHPS survey has become mandatory for hospitals to receive their full annual payment update under CMS’s inpatient prospective payment system. As reported elsewhere,10 we compared our 428 hospitals with hospitals not responding to the HCAHPS survey. The only significant difference we found was size; smaller hospitals were less likely to participate in the HCAHPS survey.

Study Results

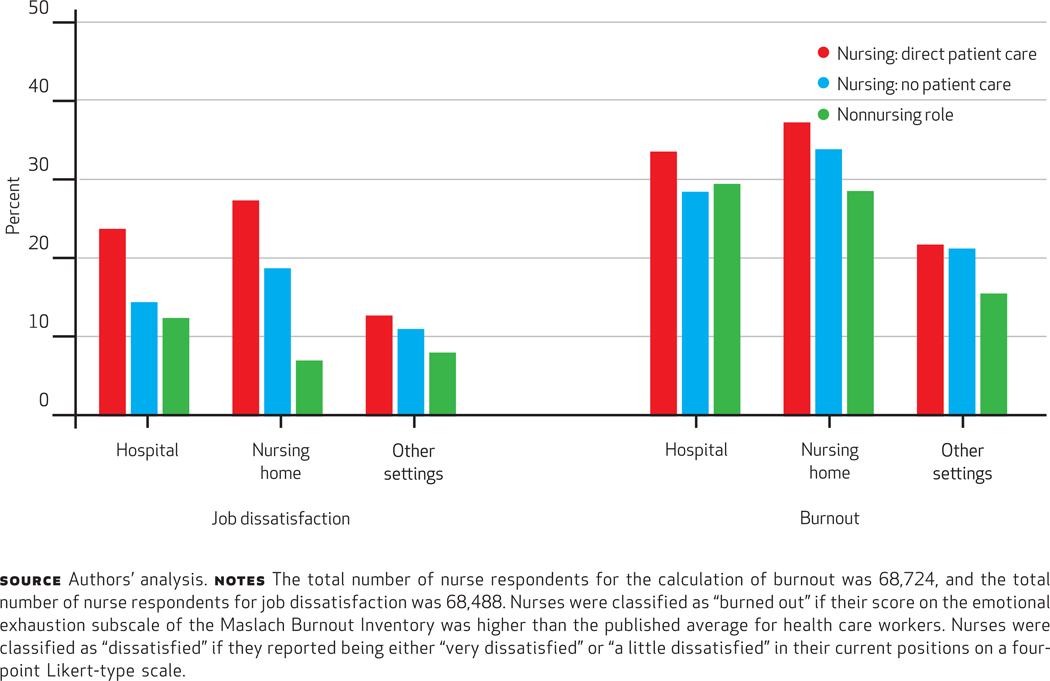

Our results focus on the nurses who were employed at the time of the survey and provided information related to burnout (n = 68; 724) and job satisfaction (n = 68; 488). Exhibit 1 provides descriptive information related to burnout and job satisfaction for nine groups of nurses defined by their work setting (hospital, nursing home, and other settings) and their role (direct patient care, no direct patient care, and nonnursing roles) within each setting.

Exhibit 1.

Percentage Of Nurses Dissatisfied And Burned Out, By Setting And Role, 2006–07

SETTING OF EMPLOYMENT

Roughly half (51 percent) of the nurses who were employed were providing direct patient care in hospitals. Nurses providing direct patient care and working in hospitals and nursing homes were statistically significantly more likely than nurses in other settings to express dissatisfaction with their jobs and to report feeling burned out. For example, of nurses providing direct patient care, 24 percent of hospital nurses and 27 percent of nursing home nurses reported dissatisfaction in their current jobs, compared to only 13 percent of nurses working in other settings. Similarly, 34 percent of hospital nurses and 37 percent of nursing home nurses reported feeling burned out in their current jobs, compared to 22 percent of nurses working in other settings.

Within settings, a significantly higher percentage of direct care nurses reported being dissatisfied and burned out in their jobs compared to nurses in the same setting but not working with patients or not working as nurses. The exception to this involved burnout among nurses working in nursing homes, which was high for nurses in all nursing home roles, but the differences were not statistically significant.

We also found that among nurses providing direct patient care, 36 percent of nurses in hospitals and 47 percent of nurses in nursing homes, compared to only 21 percent of nurses in other settings, reported that their workload caused them to miss important changes in their patients’ condition. Similar percentages of hospital nurses and nursing home nurses providing direct patient care reported that their workload caused them to fail to report important information about patients during shift changes.

JOB SATISFACTION AND BURNOUT

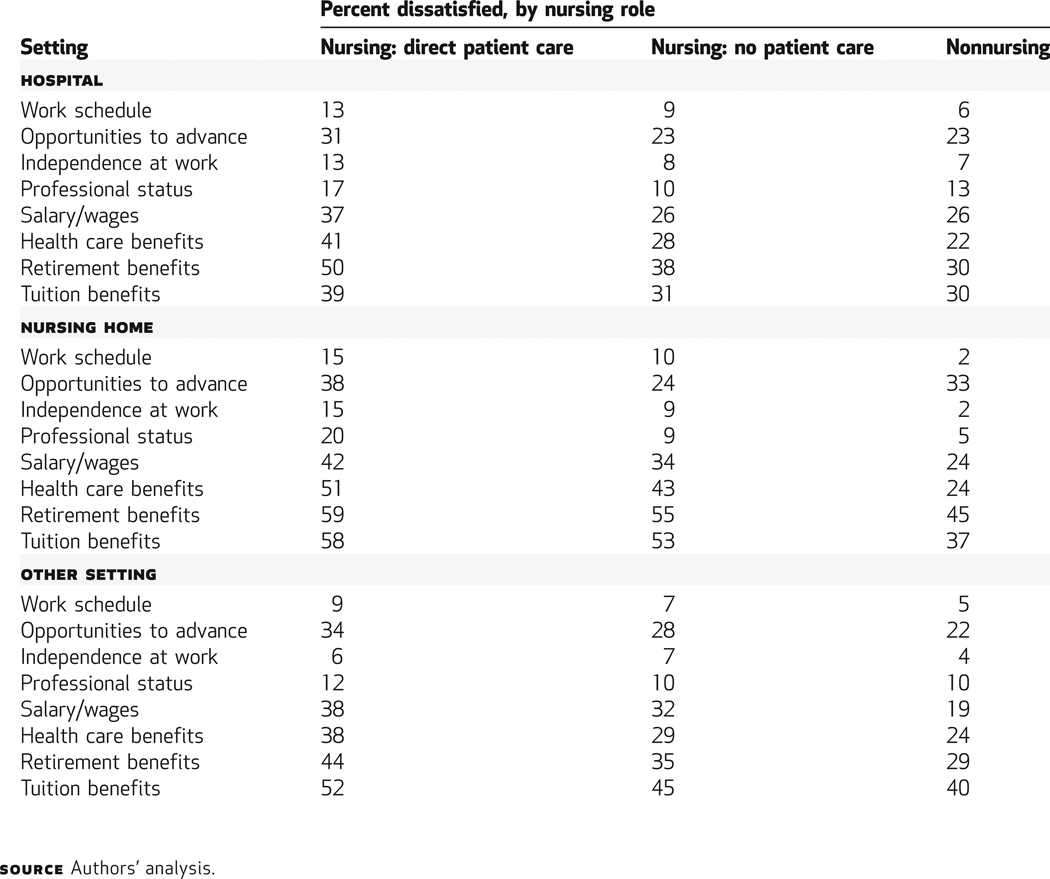

Exhibit 2 shows, for the same nine groups of nurses, differences in their satisfaction with specific aspects of their jobs, ranging from salaries and benefits to their perception of the levels of independence and professional status accorded them. Across all domains, nurses working in nursing homes and providing direct patient care exhibited the highest degree of dissatisfaction, followed by hospital nurses providing direct patient care.

Exhibit 2.

Nurses’ Dissatisfaction With Specific Aspects Of Their Jobs, By Setting And Role, 2006–07

Nurses also registered discontent with their health care and retirement benefits. Large proportions of hospital (41 percent) and nursing home (51 percent) nurses who provide direct patient care were dissatisfied with their health care benefits. Nearly 60 percent of nurses in nursing homes and half of nurses in hospitals providing direct patient care were dissatisfied with their retirement benefits.

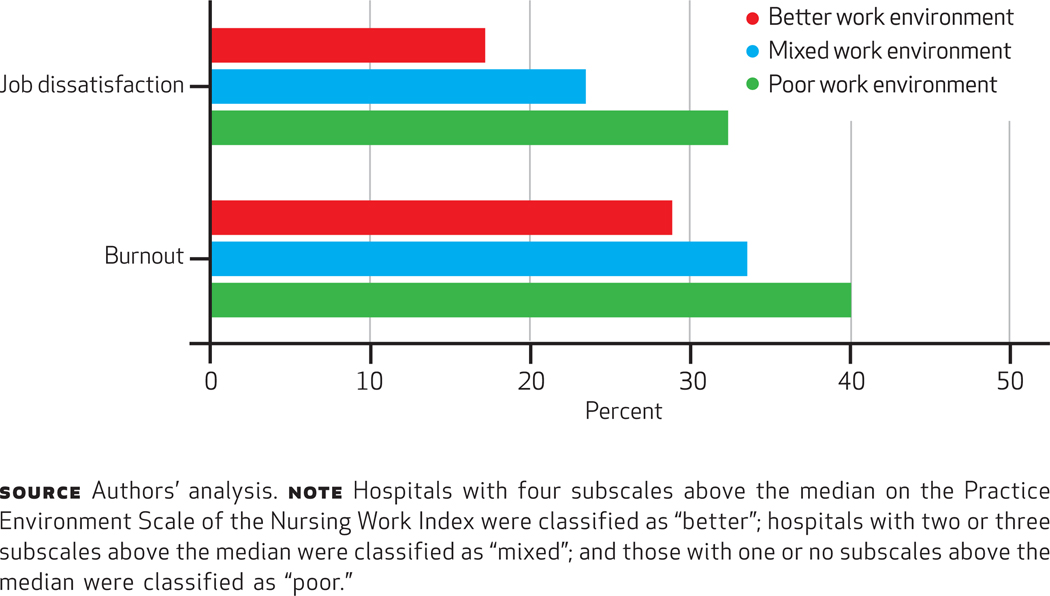

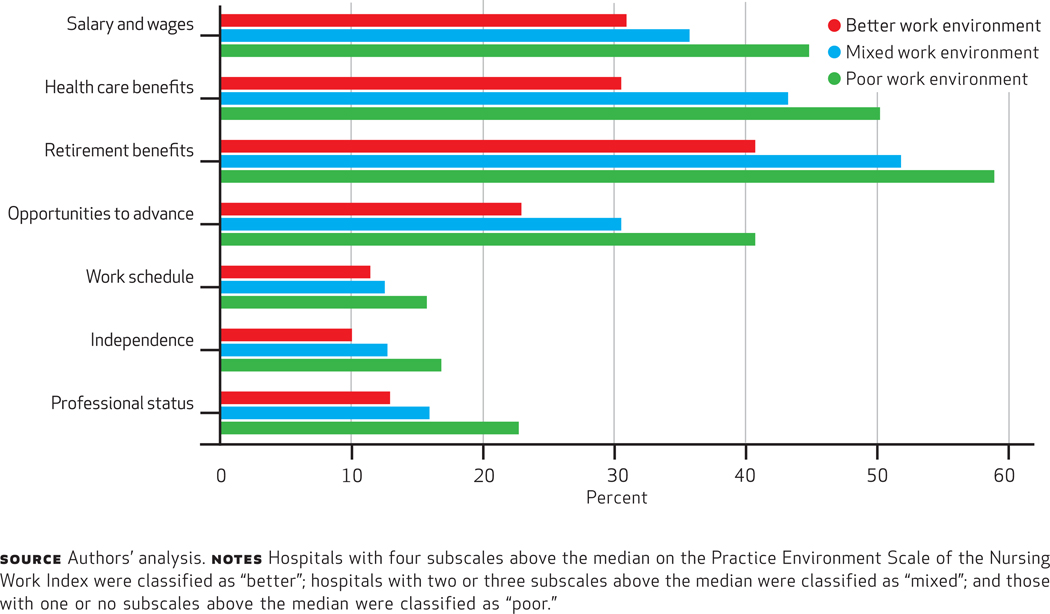

We were able to use our data to characterize the environment in which hospital nurses work. One-third of nurses practicing in hospitals with poor environments were dissatisfied; in contrast, only 17 percent of nurses practicing in hospitals with better environments were dissatisfied (Exhibit 3). Differences for burnout, although not quite as pronounced, were similarly large and statistically significant. Exhibit 4 shows that better work environments affect the satisfaction of hospital nurses providing direct patient care across all aspects of their jobs. The percentages of nurses who were very satisfied with their salaries, benefits, and other aspects of their work were significantly higher—in some cases, nearly twice as high—in hospitals with better work environments compared to hospitals with poor environments. In all cases, the percentage of nurses who were dissatisfied was highest in the hospitals with poor environments.

Exhibit 3.

Percentage Of Dissatisfied And Burned-Out Nurses Providing Direct Patient Care In Hospitals With Better, Mixed, And Poor Work Environments, 2006–07

Exhibit 4.

Percentage Of Nurses Dissatisfied With Specific Aspects Of Their Jobs In Hospitals With Better, Mixed, And Poor Work Environments, 2006–07

PATIENT SATISFACTION

We also examined the association between nurse burnout and job satisfaction, on the one hand, and patient satisfaction measured by the HCAHPS survey ratings of the hospital, on the other hand. In unadjusted models, as well as those adjusted for structural and organizational characteristics of the hospital, nurse burnout and job satisfaction had a statistically significant effect on patient satisfaction. In adjusted models, the percentage of patients who would definitely recommend the hospital to friends or family decreased by about 2 percent for every 10 percent of nurses at the hospital reporting dissatisfaction with their job, even after the effects of the work environment and nurse staffing (which also had significant effects) and a variety of hospital characteristics were controlled for. The effects were similar for the association between high burnout and the percentage of patients who gave the hospital a high rating.

Discussion And Implications

A substantial proportion of bedside nurses in hospitals and nursing homes—the primary caregivers for patients in greatest need—reported being burned out, dissatisfied with their jobs, and dissatisfied with their employee benefits. Ironically, the most satisfied and least burned-out nurses were those who did not provide direct care for patients or were not in nursing roles at all. Importantly, we found that high levels of burnout and job dissatisfaction among hospital nurses were associated with lower patient satisfaction, which signals problems with quality of care.

The contrast was particularly great between clinical care nurses in hospitals and nursing homes and those with nonclinical jobs in corporate settings such as the pharmaceutical industry. Our data show that some 24 percent of hospital staff nurses were dissatisfied with their jobs, compared to only 7 percent of nurses in pharmaceutical nonclinical jobs. A much higher percentage of hospital staff nurses also reported being burned out (34 percent) compared to their colleagues working in nonclinical pharmaceutical jobs (16 percent). Moreover, 41 percent of hospital nurses were dissatisfied with health care benefits, and 50 percent were dissatisfied with retirement benefits, compared to only 18 percent and 23 percent, respectively, in the pharmaceutical industry.

DISSATISFACTION WITH BENEFITS

It is particularly striking that there was so much dissatisfaction with health care benefits among bedside care nurses—the nation’s largest group of professionals who devote themselves to caring for others. We used data from the 2006 General Social Survey, a standard survey of social and demographic trends in the United States, to compare the job satisfaction of nurses in the pharmaceutical industry to job satisfaction in the US workforce generally and in the female, college-educated workforce in particular; we found that there are similarly low levels of dissatisfaction.

Seven percent of nurses in nonnursing pharmaceutical industry jobs reported dissatisfaction with health benefits, compared to 9.1 percent among the general US workforce. Ten percent of working women with a college degree reported dissatisfaction with health benefits.19 This suggests that nurses in caregiving roles are experiencing a distinct disadvantage relative to their peers and others in the broader workforce— a disadvantage that is likely to affect the stability of the nurse workforce in the future. Given nurses’ multiple opportunities to work in jobs with better benefits outside the hospital or nursing home setting, turnover and retention challenges may be a costly consequence for these institutions.20

CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS

The demographics of the nurse workforce have changed over the past half-century. A younger workforce with more episodic employment in the 1960s has become a rapidly aging workforce with many years of accumulated work experience. The percentage of hospital nurses above or approaching retirement age (older than age fifty-four) increased to 33 percent in 2008, from 17 percent in 1980.21

Health care institutional benefit structures designed for the younger nurse workforce of years past are increasingly out of sync with the changing demographics and employment histories of contemporary nurses. Although the majority of nurses in the United States are women (93 percent in 2008),21 their labor-force participation patterns are becoming more similar to those of American men: They increased from 41 percent labor-force participation in 1970 compared to 76 percent for men, to 57 percent in 2006 compared to 70 percent for men.22 This narrowing disparity highlights the need for a benefits review to make nurses’ benefits more comparable to those of other white-collar employees. Keeping expert nurses at the bedside will require an investment in nurses and the work they do.

WORK ENVIRONMENTS

We found that nurses’ assessments of the overall quality of their work environments—including factors such as managerial support for nursing, responsiveness of management to correcting problems in care at the bedside identified by nurses, and doctor-nurse relations—were significantly associated not only with burnout and job satisfaction, but also with nurses’ satisfaction with employee benefits, including salary. Although modifications to the work environment require a strong commitment to nursing throughout an organization, they do not all necessarily increase costs.23–25

We do not know from our survey whether actual compensation was higher in institutions where the organizational attributes of work were better, but we found that perceptions of the whole range of benefits were more positive in institutions with organizational environments more conducive to nurses’ carrying out their clinical care responsibilities successfully. Improving the organizational aspects of nurses’ work environments seems to hold promise for improving nurses’ perceptions of their jobs overall.

The National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses reported that 37 percent of nurses employed in nonnursing occupations in 2008 cited burnout or stressful work environments as the predominant reason for not working as a nurse. Although the national shortage of nurses is muted now because of economic conditions, a nurse shortage is sure to return.26 The shortage will be exacerbated by increasing demand driven by an aging population with complex, chronic, and long-term care needs.27,28

Unless the high level of dissatisfaction among nurses is addressed, health care employers are likely to see increased unrest, including work stoppages that are expensive to employers and risky to patients. Labor disputes including nursing strikes related to patient care concerns and dissatisfaction with benefits are increasingly common.29–31 Recent work by Jonathan Gruber and Samuel Kleiner32 examined the effects of nursing strikes on patient outcomes in the state of New York and showed that the hospital mortality rate was 19.4 percent higher and rates of hospital readmission were 6.5 percent higher for patients admitted during a nursing strike than among patients in nearby hospitals not affected by the strike.

CONCLUSION

Nurses’ reports about their job satisfaction and perceptions of working conditions offer an organizational barometer of how well patients are faring. Patient satisfaction is much lower in institutions where many nurses feel burned out and dissatisfied with their work conditions than in other institutions. It may be possible to improve patient satisfaction and avoid other adverse patient outcomes while also improving nurse satisfaction and retention by improving working conditions for nurses.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grants No. K08-HS017551 and No. K08-HS018534), the National Institute of Nursing Research (Grants No. R01-NR-004513 and No. T32-NR007104), and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute of Nursing Research, or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The funding sources had no role in the study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; or writing of the report. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Evan Wu with data preparation and analysis, as well as that of Aria Mahtabfar and Erin Schelar with the preparation of the manuscript.

Biographies

Matthew D. McHugh is an assistant professor of nursing at the University of Pennsylvania.

Matthew McHugh and his coauthors are long-time collaborators at the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. As part of a program that studies how the circumstances of nurses’ work lives affect patient care outcomes, they designed and implemented the study of nearly 100,000 nurses on which their paper in this issue is based.

Among their findings: There is much higher job dissatisfaction and burnout among nurses directly caring for patients in hospitals and nursing homes than in other settings—and patients in these settings are less satisfied with their care. Thus, the authors conclude, improving nurses’ working conditions may improve the experiences of both nurses and patients.

Surprisingly, the study also revealed nurses’ dissatisfaction with their health and retirement benefits—a finding that the authors attribute partly to an out-of-date benefit structure. “Our findings suggest that current labor practices are at odds with changes in the hospital workforce,” McHugh says. “Human resource policies evolved when the nurse workforce was younger, more transient, less educated, and relatively cheap.” Now that the overwhelmingly female and older nursing workforce more closely resembles the broader workforce, a benefits review is warranted, the authors assert.

McHugh is an assistant professor of nursing at the Penn School of Nursing. He received a doctorate in nursing from the University of Pennsylvania, as well as a master of public health degree from the Harvard School of Public Health and a law degree from the Northeastern University School of Law. His research focuses on patient outcomes and nursing practices.

Ann Kutney-Lee is an assistant professor of nursing at the University of Pennsylvania.

Ann Kutney-Lee is an assistant professor of nursing at the Penn School of Nursing, where her research focuses on the organization of nursing delivery systems and outcomes for patients with chronic illnesses. She also received a doctorate in nursing from the University of Pennsylvania.

Jeannie P. Cimiotti is a research assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

Jeannie Cimiotti is a research assistant professor at the Penn School of Nursing and a senior fellow of the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at Penn’s Wharton School. She specializes in the organization of hospital nursing services and health care outcomes, especially among infants and children. She has a master’s degree in nursing from Rutgers University–Newark and a doctorate in nursing science from Columbia University.

Douglas Sloane is a sociologist and adjunct professor at the Penn School of Nursing, and assistant director, social science analyst, and supervisory statistician at the Government Accountability Office, in Washington, D.C. He earned master’s and doctoral degrees in sociology from the University of Arizona.

Linda H. Aiken directs the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research at the Penn School of Nursing.

Linda Aiken is the Claire M. Fagin Leadership Professor of Nursing and Sociology. She directs the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research at the Penn School of Nursing and is a senior fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute. Her research focuses on the outcomes of nursing care in the United States and around the world. She has won numerous awards for her research. She has a doctorate in sociology from the University of Texas at Austin and is a member of the Health Affairs editorial board.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting, June 28, 2010, in Boston, Massachusetts.

Contributor Information

Matthew D. McHugh, Email: mchughm@nursing.upenn.edu, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia.

Ann Kutney-Lee, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

Jeannie P. Cimiotti, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

Douglas M. Sloane, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

Linda H. Aiken, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

NOTES

- 1.Wachter RM. Patient safety at ten: unmistakable progress, troubling gaps. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(1):165–173. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0804116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ejaz FK, Noelker LS, Schur D, Whitlatch CJ, Looman WJ. Family satisfaction with nursing home care for relatives with dementia. J Appl Gerontol. 2002;21(3):368–384. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski JA, Busse R, Clarke H, et al. Nurses’ reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(3):43–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine. Keeping patients safe: transforming the work environment of nurses. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maslach C, Schaufeli W, Leiter M. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2008;38(5):223–229. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000312773.42352.d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vahey DC, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Clarke SP, Vargas D. Nurse burnout and patient satisfaction. Med Care. 2004;42(2 Suppl):II57–II66. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000109126.50398.5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Cimiotti JP, Clarke SP, Flynn L, Seago JA, et al. Implications of the California nurse staffing mandate for other states. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(4):904–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kutney-Lee A, McHugh MD, Sloane DM, Cimiotti JP, Flynn L, Neff DF, et al. Nursing: a key to patient satisfaction. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(4):w669–w677. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giordano LA, Elliott MN, Goldstein E, Lehrman WG, Spencer PA. Development, implementation, and public reporting of the HCAHPS survey. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(1):27–37. doi: 10.1177/1077558709341065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith HL. A double sample to minimize bias due to nonresponse in a mail survey. In: Ruiz-Gazen A, Guilbert P, Haziza D, Tille Y, editors. Survey methods: applications to longitudinal investigations, health, electoral investigations, and investigations in the developing countries. Paris: Dunod; 2008. pp. 334–339. [Google Scholar]

- 13.To Access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 14.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach Burnout Inventory manual. 2nd ed. Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychologists Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maslach C, Jackson SE. Burnout in health professions: a social psychological analysis. In: Sanders GS, Suls J, editors. Social psychology of health and illness. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1982. pp. 227–251. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lake ET, Friese CR. Variations in nursing practice environments: relation to staffing and hospital characteristics. Nurs Res. 2006;55(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200601000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lake ET. Development of the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index. Res Nurs Health. 2002;25(3):176–188. doi: 10.1002/nur.10032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis JA, Smith TW, Marsden PV. General Social Surveys, 1972–2008: cumulative codebook. Chicago (IL): University of Chicago, National Opinion Research Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waldman JD, Kelly F, Arora S, Smith HL. The shocking cost of turnover in health care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2004;29(1):2–7. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200401000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Health and Human Services. The registered nurse population: findings from the 2008 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses. Washington (DC): Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Civilian population—employment status by sex, race, and ethnicity: 1970 to 2008 [Internet] Washington (DC): BLS; 2010. [cited 2010 Dec 22]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2010/tables/10s0576.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dall TM, Chen YJ, Seifert RF, Maddox PJ, Hogan PF. The economic value of professional nursing. Med Care. 2009;47(1):97–104. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181844da8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mark BA, Lindley L, Jones CB. Nurse working conditions and nursing unit costs. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2009;10(2):120–128. doi: 10.1177/1527154409336200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothberg MB, Abraham I, Lindenauer PK, Rose DN. Improving nurse-to-patient staffing ratios as a cost-effective safety intervention. Med Care. 2005;43(8):785. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000170408.35854.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buerhaus PI, Auerbach DI, Staiger DO. The recent surge in nurse employment: causes and implications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(4):w657–w668. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin LG, Freedman VA, Schoeni RF, Andreski PM. Trends in disability and related chronic conditions among people ages fifty to sixty-four. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(4):725–731. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thorpe KE, Ogden LL, Galactionova K. Chronic conditions account for rise in Medicare spending from 1987 to 2006. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(4):718–724. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Washington Post: 2010. Jun 11, Associated Press. Nurses in Minnesota stage day-long strike; p. A3. [Google Scholar]

- 30.New York Times: 2007. Oct 2, Associated Press. Nurses go on strike; p. A21. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burling S. Temple Hospital nurses could strike. Philadelphia Inquirer. 2009 Sep 22;:C2. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gruber J, Kleiner SA. Evidence from New York State. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2010. Do strikes kill? (Working Paper; No. 15855) [Google Scholar]