Abstract

Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) is a new approach to generate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast that allows monitoring of protein properties in vivo. In this method, radiofrequency is used to saturate the magnetization of specific protons on a target molecule, where it is then transferred to water protons via chemical exchange and detected using MRI. One advantage of CEST imaging is that the magnetization of the different protons can be specifically saturated at different resonance frequencies. This enables the detection of multiple targets simultaneously in living tissue. We present here a CEST MRI approach to detect the activity of Cytosine Deaminase (CDase), an enzyme that catalyzes the deamination of cytosine to uracil. Our findings suggest that metabolism of two substrates of the enzyme, cytosine and 5-fluorocytosine (5FC), can be detected using saturation pulses targeted specifically to protons at +2 ppm and +2.4 ppm (with respect to water), respectively. Indeed, after deamination by recombinant CDase, the CEST contrast disappears. In addition, expression of the enzyme in three different cell lines, each with different expression levels of CDase, show good agreement with the CDase activity measured with CEST MRI. Consequently, CDase activity was imaged with high-resolution CEST-MRI. These data demonstrate the ability to detect enzyme activity based on proton exchange. Consequently, CEST MRI has the potential to follow the kinetics of multiple enzymes in real-time in living tissue.

In order to study proteins and enzymes in their natural context in living organisms, a non-invasive imaging technique with high spatial and temporal resolution is required. Such resolution can be achieved using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which has been used extensively in the last two decades for anatomical, functional, and dynamic imaging. Detection with MRI relies on contrast in the MRI signal between the tissue of interest and its surrounding tissue, which can be further enhanced by expressing certain exogenous proteins that increase MRI contrast. Recently, a new type of MR contrast has been developed that relies on direct chemical exchange of protons with bulk water. A variety of organic molecules1–6 and lanthanide complexes,7–10 which possess protons that exchange rapidly with the surrounding water protons, have been suggested as powerful new contrast agents. These exchangeable protons can be “magnetically tagged” using a radiofrequency saturation pulse applied at their resonance frequency. The tagged protons exchange with the protons of surrounding water molecules, and, consequently, reduce the MRI signal. This itself would not be visible at the low concentrations of solute, but the exchanged protons are replaced with fresh, unsaturated protons and the same saturation process is repeated. After several seconds of this process, the effect becomes amplified and very low concentrations of agents can be detected. Hence, these agents are termed Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) contrast agents. One main advantage of CEST MRI is the possibility to generate MRI contrast using bio-organic molecules, such as polysaccharides (sugars), proteins, enzymes, and substrates that can be non-invasively detected in tissue3,4,11,12.

CEST-MRI was previously used to detect enzyme activity using paramagnetic (PARACEST) substrates, which rely on a shift in the water exchange frequency after the enzymatic reaction10,13–15. Here, we use the enzyme Cytosine Deaminase (CDase) to demonstrate the feasibility of using CEST MRI as a specific tool for non-invasive, real-time imaging of enzyme activity using metal-free bio-organic diamagnetic substrates (DIACEST). CDase is an enzyme that is expressed exclusively in bacteria and fungi, as an important part of the pyrimidine salvage pathway. CDase catalyzes the conversion of cytosine to uracil through the removal of an amine group, or “deamination.” 16 It can also convert the pro-drug, 5-fluorocytosine (5FC), to a chemotherapeutic agent, 5-fluorouracil (5FU), making it a promising enzyme/prodrug system for cancer therapy17. Because CDase activity is absent in mammalian cells, the administration of 5FC is not likely to result in significant toxicity to normal tissue. Since amine groups contain two exchangeable protons, we hypothesized that deamination of cytosine or 5FC by CDase to generate uracil or 5FU should be detectable by CEST MRI (Figure 1).

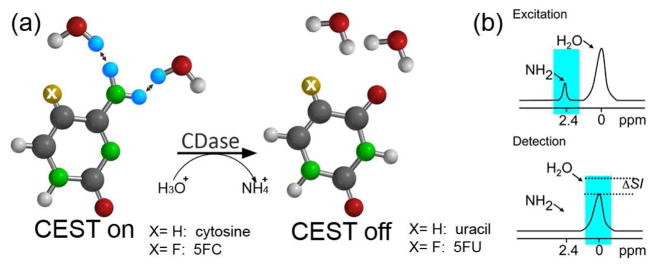

Figure 1.

(a) CDase catalyzes the deamination of both cytosine and 5FC to uracil and 5FU, respectively. (b) A frequency-selective saturation pulse is applied to label the amine protons (cyan) of cytosine or 5FC. The labeled protons exchange with water protons, which leads to a reduction in MRI signal intensity in a frequency- selective manner, generating CEST contrast.

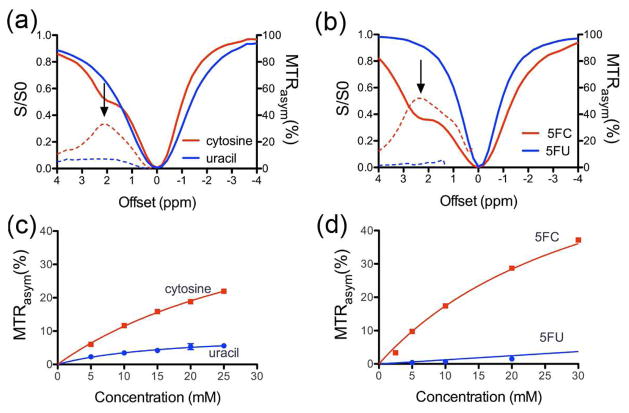

First, we determined whether CEST MRI could detect the CDase substrates and products with sufficient sensitivity under physiological conditions. We examined the CEST contrast generated by cytosine, uracil, 5FC, and 5FU over a range of concentrations at pH=7.4 and 37°C. The solid lines in Figure 2a and 2b represent the CEST spectra, in which the water proton signal is plotted as a function of saturation frequency. The dashed lines represent plots of MTRasym, a measure of CEST contrast defined by: MTRasym=(S−Δω − SΔω)/S0, where S−Δω and SΔω are the MRI signal intensities after saturation at − and + the offset frequency Δω from the water proton frequency (which is set at 0 ppm by convention) and S0, the intensity in the absence of a saturation pulse. The maximal MTRasym values for cytosine and 5FC were obtained at offsets of +2 ppm and +2.4 ppm, respectively. In contrast, uracil and 5FU, which do not have an NH2 group, showed only limited and nonfrequency specific MTRasym, the origin of which is not confirmed but probably due to the rapidly exchanging (1- or 3-) imino NH protons. Figures 2c and 2d show the dynamic range of these substrate concentrations that can be detected with CEST MRI. These findings indicate that CEST MRI is suitable for monitoring the deamination of cytosine and 5FC.

Figure 2.

CEST properties of cytosine, uracil, 5FC, and 5FU at 9.4 Tesla at pH=7.4 and 37°C. CEST-spectra (solid line) and MTRasym plots (dashed line) of (a) 40 mM cytosine (red), uracil (blue), and (b) 40 mM 5FC (red) and 5FU (blue). Arrows point to the maximal MTRasym. Concentration dependencies of MTRasym at 2 ppm and 2.4 ppm are shown for cytosine and uracil (c), and 5FC and 5FU (d), respectively.

We determined the exchange rate (kex) by measuring the MTRasym as a function of saturation time as described previously2 (Figure S1, Supporting Information). For the amine protons of cytosine, we found kex = 8.1 × 102 Hz. We then verified this number using an alternative approach, the frequency-labeled exchange (FLEX) transfer method18, which gave kex = 9.3 × 102 Hz (Figure S2, supporting information), which is in good agreement. For the amine proton of 5FC, kex was found to be 1.8 × 103 Hz (Figure S1, Supporting Information). For both cytosine and 5FC, kex is on the order of magnitude of the frequency difference with water (Δω), in the intermediate exchange range. Notice that CEST can still detect such rapidly exchanging protons, as long as some partial saturation can be achieved while the proton is at the correct frequency. This is an advantage over conventional MRI, where it would not be detectable. This has previously allowed even detection of OH groups4.

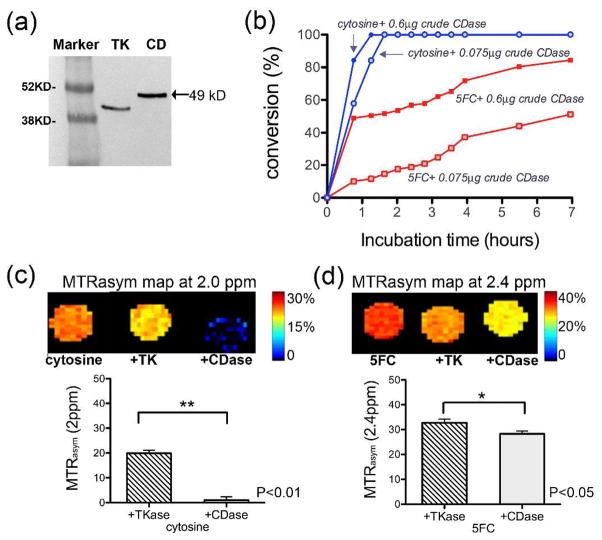

Next, we evaluated the detection of recombinant CDase activity with CEST MRI. The gene encoding the Escherichia coli (E. coli) CDase (CodA) was cloned into an expression vector (pEXP5-CT; Invitrogen) in a reading frame with a six-histidine C-terminal tag under the regulation of the T7 promoter. The gene encoding the herpes simplex virus type-1 thymidine kinase (HSV1-tk) was used as control. Both enzymes were over-expressed in E. coli (BL21) and a crude protein extract was used to measure enzymatic activity with MRI. As shown in Figure 3b, with recombinant CDase, substrate conversions where MTR0asym and MTRtasym are the contrast at the initial time point (0) or a subsequent time point (t), respectively, could be measured for both cytosine and 5FC. Figure 3c,d both demonstrate that the reduction in the MTRasym in the presence of CDase is significantly larger than in the presence of the control enzyme, HSV1-tk. While the conversion of cytosine was nearly complete after 24 hours, this was not the case for 5FC. This can be attributed to the lower specificity of CDase toward 5FC, compared to its natural substrate cytosine19. A slight reduction in the MTRasym was also observed in the extract containing recombinant HSV1-tk, possibly due to endogenous CDase activity.

Figure 3.

Monitoring recombinant CDase activity using CEST MRI. (a) Western blot using an anti-six-histidine tag antibody of protein extracts from E. coli engineered to express CD or HSV1-tk (TK). (b) Deamination of cytosine and 5FC (20 mM) by crude CDase extracts measured using CEST MRI at 37 °C and 9.4T. Conversion is quantified as (1−MTRtasym/MTR0asym)×100%, with MTR0asym and MTRtasym the contrast at initial and subsequent time points, respectively. (c, d). Maps and statistical analysis (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; n=3) of 20 mM (c) cytosine and (d) 5FC incubated with CDase (0.6μg crude protein) for 24 hours.

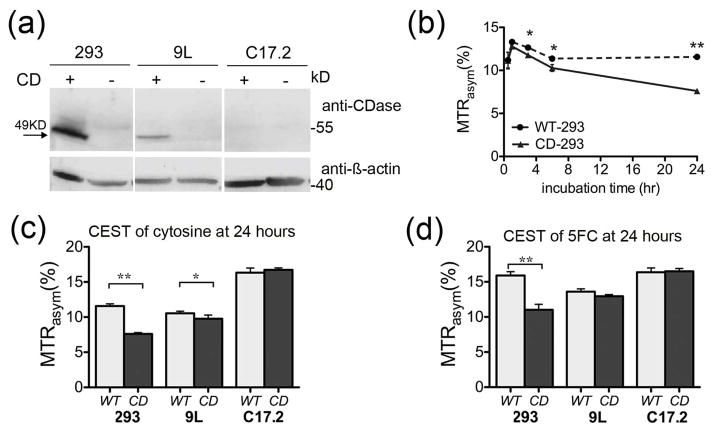

Therefore, we tested the CDase activity in mammalian cells that do not express endogenous CDase. A lentivirus that encodes CDase under the CMV promoter was constructed. The lentivirus was used to transduce three different cell lines in culture. As seen in Figure 4a, each cell line expressed different levels of CDase. Human embryonic kidney (HEK293FT) cells expressed the highest amount, 9L rat glioma expressed an intermediate level, and C17.2 mouse neural stem cells failed to express the enzyme at a detectable level.

Figure 4.

Detection of CDase in mammalian cells. (a) Western blot wild type (WT) or CDase-transduced HEK293FT (293), 9L and C17.2 cells stained with anti-CDase and anti-β-actin for total protein. (b) MTRasym of the supernatant of culture media of HEK293FT cells transduced with CD (CD-293), or control (WT-293) collected at different time points after incubation with 7 mM cytosine. (c,d) MTRasym of the culture media 24 hours after incubation with 7 mM cytosine (c) and 10 mM 5FC (d) at 2.0 and 2.4 ppm, respectively. In c–d, WT and CD represent transduced and non-transduced cells respectively. (*) p< 0.05 and (**) p<0.01 (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test).

For each cell type, the same number of transduced or untransduced (wild type; WT) cells were plated (5.6×106 HEK293FT, 106 9L, and 1.4×106 C17.2 cells, respectively). Fresh culture media containing 7 mM cytosine or 10 mM 5FC was added to the cells. Fifty microliters of the culture media were collected at different time points up to 48 hours, and measured with CEST-MRI in capillaries, as described previously20. Figure 4b demonstrates a significant difference in MTRasym between transduced and non-transduced HEK293FT cells as early as 4 hours after incubation with 7 mM cytosine. This is in good agreement with the high expression level of CDase by those cells. In contrast, for cells treated with 10 mM 5FC, a significant difference in MTRasym was observed only after 24 hours (Figure S3, Supporting Information). Figure 4b shows an initial increase in the MTRasym at the initial time points. We tentatively attribute this to small changes in the ratio of enzyme to substrate, which may be the result of reducing the volume of the solution due to the sampling methods or of evaporation of minute amounts of the media over time. Alternatively, changes in the pH of the cell culture media may affect the MTRasym. Nevertheless, the experimental results show a significant difference between CDase expressing cells and controls, indicating the ability to monitor enzyme activity directly. Figure 4c,d show the difference in MTRasym for all cell lines after 24 hours of incubation with cytosine and 5FC, respectively. At this time point, the HEK293FT cells showed a significant difference in MTRasym for both cytosine and 5FC. The 9L cells, which exhibited an intermediate expression level of CDase, showed a moderate reduction of MTRasym only for cytosine, but not for 5FC. The C17.2 cells, which had undetectable CDase expression, showed no difference in MTRasym at this time point. (A complete time course of CEST MRI, validation with 19F-MR spectroscopy, and a cell viability assay can be found in Figures S3–S5, Supporting Information).

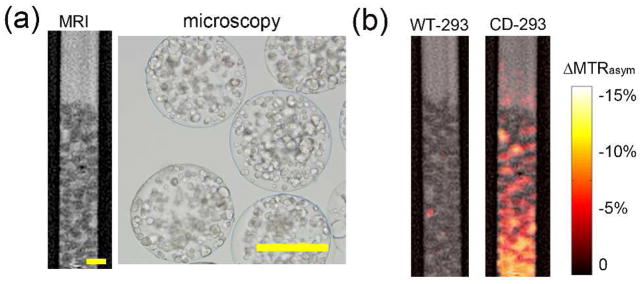

Immunoprotected cells have been evaluated as a new therapeutic alternative, for example, for pancreatic islet cell replacement in diabetic patients. In this approach, cells are encapsulated with alginate that enables passage of essential factors (e.g., nutrients and insulin), but protects cells from attack by the body’s immune system. Several methods have been successfully developed to monitor encapsulated cells after transplantation21–24. Yet, a non-invasive method to visualize the viability of the transplant would be highly beneficial. In order to evaluate the feasibility of this method in cells, we encapsulated HEK293FT expressing CDase or non-expressing control cells. As can be seen in Figure 5, when incubating with 5FC, only the CDase-expressing cells (CD-293) showed conversion of 5FC (initial concentration of 30 mM) within the first 3 hours. Based on the cytotoxic mechanism of 5FU, it is unlikely that there is a contribution of cell death to the change in the MTRasym. These findings indicate that CDase activity can be imaged at the macro-cellular level in 3D culture. In addition, the CDase may be used not only to monitor the transplant viability, but also as a suicide gene, which can be used to eradicate transplanted cells in case of tumorigenic transformation of the transplanted cells.25

Figure 5.

Imaging of cellular enzyme activity: CEST-MRI of HEK293FT cells transduced with CDase (CD-293) or control cells (WT-293) encapsulated within alginate (200–300 cells per microcapsule). (a) High-resolution MR image (90×50 μm, left) with corresponding microscopy (right). Scale bars = 400 μm. (b) Conversion map overlaid on T2-weighted images clearly shows that CD-293 cells, but not WT-293 cells, effectively converted 5FC to 5FU with a concurrent change in CEST signal.

This study demonstrates that the activity of the enzyme CDase can be monitored using CEST MRI. Previously, such detection was possible using 19F MR spectroscopy26,27 and 19FMR spectroscopic imaging28, which rely on a change in chemical shift upon conversion of 5FC to 5FU. One advantage of using CEST MRI is that there is no requirement for using a toxic prodrug (5FC). Instead, the CDase’s natural substrate, cytosine, can be used for imaging. This allows repetitive measurements and the use of CDase as a reporter gene. Another advantage is that CEST MRI can be used for monitoring multiple enzymes simultaneously, as long as their substrates have exchangeable protons that resonate at distinct frequencies. This property is relevant for studying gene networks, for example, in signal transduction cascade pathways.

An additional potential application may be real-time monitoring of the efficiency of therapeutic gene delivery and expression. As CDase has already entered the clinic for cancer gene therapy29, such real-time monitoring may aid in predicting treatment outcomes. Since different cells or tumors may express differential levels of CDase, different patients may respond differently. Hence, real-time monitoring of enzymatic activity by CEST MRI could guide personalized medicine. Nevertheless, before this method can be fully translated, several hurdles must be overcome. Among those is optimization of the sensitivity of the substrates. The sensitivity in vivo depends on the expression levels of the enzyme, the cell density and accessibility of the substrate to the CDase expressing cells. Our in vitro data indicate that recombinant CDase from 106 mammalian cells is sufficient to significantly reduce the MTRasym upon incubation with 7 mM cytosine or 10 mM 5FC. This number of cells is on the same order of magnitude as used in cell mediated CDase cancer gene therapy in vivo studies30–32. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of CEST MRI (Figure S3, Supporting Information) is approximately 80 comparing to SNR of 160 for 19F-NMR (Figure S4 & Table S1). However, for the same level of CDase expressed by 9L cells, after 48 hours incubation with 5FC, a relative change in MTRasym of 12% was observed compared to 8.5% change measured using 19F-NMR. With cytosine as the substrate, at the same conditions, a much higher change (i.e. 50%) was observed with CEST MRI. Thus, the sensitivity of the CEST MRI is comparable to that of conventional 19F-NMR26,27.

More than 5% change in the MTRasym was detected from 200–300 cells encapsulated in each alginate bead of 400–500μm in diameter. As a 3D multicellular spheroid at diameter of 300 μm consists of 3900 cells33, CEST MRI is expected to allow measurement of CDase activity even when only 5–10% of the cells would be expressing the enzyme. Taken together, the present CEST MRI approach is expected to be sufficiently sensitive for future pre-clinical or clinical applications.

In addition, CEST contrast is highly dependent on the exchange rate34, which can be modified using chemical modifications. This would be aimed towards increasing the MTRasym of the amine protons as well as the imino protons. The latter can be achieved by reducing the exchange rate at physiological pH, which may produce CEST contrast at 5–6ppm. This will allow reduction of the applied B1, thereby decreasing the background from endogenous magnetization transfer effects as well as from direct water saturation. Shortening the image acquisition time is also required for improving the temporal resolution, which will allow more accurate dynamic measuring of the enzyme activity. Moreover, the enzyme turnover rate for substrates can be improved using genetic manipulations. The turnover rate was significantly improved when the entire gene35, or just its active site36, were subjected to directed evolution. It is noteworthy that T2 exchange effects may cause CEST agents to behave as T2 agents, causing darkening of the image37. However, this is not a problem for the current agents at the low concentration used and the chemical shift difference for these DIACEST agents. Finally, the detection may be improved by controlling the levels of the agents, for example by sustained release38.

In summary, we have demonstrated here that CEST MRI, a novel approach to producing contrast based on proton exchange, can be used for direct monitoring of CDase activity in real-time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants EB008769, NS065284, EB005252, EB012590, EB006394 and EB015032. The authors thank Dr. Raag D. Airan for his comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, MRI acquisition, and data processing methods are included in the Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via internet at http://pubs.acs/org.

References

- 1.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. J Magn Reson. 2000;143:79. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMahon MT, Gilad AA, Zhou J, Sun PZ, Bulte JW, van Zijl PC. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006;55:836. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Zijl PC, Jones CK, Ren J, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Zijl PC, Yadav NN. Magn Reson Med. 2011 doi: 10.1002/mrm.22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou J, Payen JF, Wilson DA, Traystman RJ, van Zijl PCM. Nature medicine. 2003;9:1085. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherry AD, Woods M. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2008;10:391. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terreno E, Castelli DD, Cravotto G, Milone L, Aime S. Investigative radiology. 2004;39:235. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000116607.26372.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinogradov E, He H, Lubag A, Balschi JA, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:650. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoo B, Pagel MD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14032. doi: 10.1021/ja063874f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilad AA, McMahon MT, Walczak P, Winnard PT, Jr, Raman V, van Laarhoven HW, Skoglund CM, Bulte JW, van Zijl PC. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:217. doi: 10.1038/nbt1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haris M, Cai K, Singh A, Hariharan H, Reddy R. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2079. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suchy M, Ta R, Li AX, Wojciechowski F, Pasternak SH, Bartha R, Hudson RHE. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 2010;8:2560. doi: 10.1039/b926639a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chauvin T, Durand P, Bernier M, Meudal H, Doan BT, Noury F, Badet B, Beloeil JC, Tóth É. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2008;47:4370. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoo B, Raam MS, Rosenblum RM, Pagel MD. Contrast Media & Molecular Imaging. 2007;2:189. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishiyama T, Kawamura Y, Kawamoto K, Matsumura H, Yamamoto N, Ito T, Ohyama A, Katsuragi T, Sakai T. Cancer research. 1985;45:1753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aghi M, Hochberg F, Breakefield X. The Journal of Gene Medicine. 2000;2:148. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-2254(200005/06)2:3<148::AID-JGM105>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman JI, McMahon MT, Stivers JT, Van Zijl PC. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1813. doi: 10.1021/ja909001q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porter DJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1476:239. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu G, Gilad AA, Bulte JW, van Zijl PC, McMahon MT. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2010;5:162. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arifin DR, Long CM, Gilad AA, Alric C, Roux Sp, Tillement O, Link TW, Arepally A, Bulte JWM. Radiology. 2011;260:790. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnett BP, Arepally A, Karmarkar PV, Qian D, Gilson WD, Walczak P, Howland V, Lawler L, Lauzon C, Stuber M, Kraitchman DL, Bulte JW. Nat Med. 2007;13:986. doi: 10.1038/nm1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnett BP, Arepally A, Stuber M, Arifin DR, Kraitchman DL, Bulte JW. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:1142. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim J, Arifin DR, Muja N, Kim T, Gilad AA, Kim H, Arepally A, Hyeon T, Bulte JW. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:2317. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao F, Drukker M, Lin S, Sheikh AY, Xie X, Li Z, Connolly AJ, Weissman IL, Wu JC. Cloning Stem Cells. 2007;9:107. doi: 10.1089/clo.2006.0E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stegman L, Rehemtulla A, Beattie B, Kievit E, Lawrence T, Blasberg R, Tjuvajev J, Ross B. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:9821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aboagye E, Artemov D, Senter P, Bhujwalla Z. Cancer research. 1998;58:4075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gade TP, Koutcher JA, Spees WM, Beattie BJ, Ponomarev V, Doubrovin M, Buchanan IM, Beresten T, Zakian KL, Le HC, Tong WP, Mayer-Kuckuk P, Blasberg RG, Gelovani JG. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2878. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freytag SO, Khil M, Stricker H, Peabody J, Menon M, DePeralta-Venturina M, Nafziger D, Pegg J, Paielli D, Brown S, Barton K, Lu M, Aguilar-Cordova E, Kim JH. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kucerova L, Altanerova V, Matuskova M, Tyciakova S, Altaner C. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6304. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aboody KS, Brown A, Rainov NG, Bower KA, Liu S, Yang W, Small JE, Herrlinger U, Ourednik V, Black PM, Breakefield XO, Snyder EY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimato S, Natsume A, Takeuchi H, Wakabayashi T, Fujii M, Ito M, Ito S, Park I, Bang J, Kim S. Gene therapy. 2007;14:1132. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutherland RM. Science. 1988;240:177. doi: 10.1126/science.2451290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snoussi K, Bulte JW, Gueron M, van Zijl PC. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:998. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahan SD, Ireton GC, Knoeber C, Stoddard BL, Black ME. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2004;17:625. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuchita M, Ardiani A, Zhao L, Serve K, Stoddard BL, Black ME. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4791. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soesbe TC, Merritt ME, Green KN, Rojas- Quijano FA, Sherry AD. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2011:n/a. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi J, Kim K, Kim T, Liu G, Bar-Shir A, Hyeon T, McMahon MT, Bulte JWM, Fisher JP, Gilad AA. Journal of Controlled Release. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.06.035. In Press, Accepted Manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.