Abstract

Rationale

Thymosin beta-4 (Tβ4) is a ubiquitous protein with diverse functions relating to cell proliferation and differentiation that promotes wound healing and modulates inflammatory responses. The effecter molecules targeted by Tβ4 for cardiac protection remains unknown. The purpose of this study is to determine the molecules targeted by Tβ4 that mediate cardio-protection under oxidative stress.

Methods

Rat neonatal fibroblasts cells were exposed to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in presence and absence of Tβ4 and expression of antioxidant, apoptotic and pro-fibrotic genes was evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR and western blotting. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels were estimated by DCF-DA using fluorescent microscopy and fluorimetry. Selected antioxidant and antiapoptotic genes were silenced by siRNA transfections in cardiac fibroblasts and the effect of Tβ4 on H2O2-induced profibrotic events was evaluated.

Results

Pre-treatment with Tβ4 resulted in reduction of the intracellular ROS levels induced by H2O2 in the cardiac fibroblasts. This was associated with an increased expression of antioxidant enzymes Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase and reduction of Bax/Bcl2 ratio. Tβ4 treatment reduced the expression of pro-fibrotic genes [connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), collagen type-1 (Col-I) and collagen type-3 (Col-III)] in the cardiac fibroblasts. Silencing of Cu/Zn-SOD and catalase gene triggered apoptotic cell death in the cardiac fibroblasts, which was prevented by treatment with Tβ4.

Conclusion

This is the first report that exhibits the targeted molecules modulated by Tβ4 under oxidative stress utilizing the cardiac fibroblasts. Tβ4 treatment prevented the profibrotic gene expression in the in vitro settings. Our findings indicate that Tβ4 selectively targets and upregulates catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD and Bcl2, thereby, preventing H2O2-induced profibrotic changes in the myocardium. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the signaling pathways involved in the cardio-protection afforded by Tβ4.

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) plays an important role in regulating a variety of cellular functions, including gene expression, cell growth and cell death and has been implicated as one of the major contributors of cardiac damage in various cardiac pathologies [1], [2], [3]. Increased ROS levels can cause damage to nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins and can directly damage the vascular cells, cardiac myocytes and cardiac fibroblasts [3], [4]. Oxidative stress has been shown to be a precursor of cardiac apoptosis and has also been implicated in cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis [5], [6], [7]. The declining protective enzymes and the reduced adaptive capacity to counter the oxidative stress cause activation of apoptotic death pathways [8]. Although, cells, tissues and organs utilize multiple layers of antioxidant defenses and damage removal, the heart is particularly more vulnerable to oxidative damage as it has a weak endogenous antioxidant defense system [9].

It has been suggested that an increased level of oxidative stress heart is primarily due to the functional uncoupling of the respiratory chain caused by inactivation of complex I in the mitochondria [10] or due to impaired antioxidant capacity, such as reduced activity of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (Cu/Zn-SOD) and catalase [6], or stimulation of enzymatic sources, including xanthine oxidase, cyclo-oxygenase, nitric oxide synthase, and non-phagocytic NAD(P)H oxidases [11]. Irrespective of the source of the stress stimuli involved, oxidative damage remains the main challenge and numerous efforts have been made to devise strategies to protect the heart against oxidative damage. Considerable attempts have been made in the recent decades to discover an “ideal” cardio-protective agent, which can abrogate the oxidative damage and maladaptive changes in the heart. In this pursuit, thymosin β4 (Tβ4) emerged as a powerful candidate.

Tβ4, a 43 amino acids, ubiquitous intracellular protein, bind to and sequester G- actin to modulate cell migration [12]. Recent studies implicated that Tβ4 had multiple diverse physiological and pathological functions, such as wound healing, angiogenesis, preserved cardiac function after myocardial infarction which essentially depends on cell migration [13], [14], [15]. Essentially, Tβ4 possesses cardiac tissue repair properties that cause epicardial cell migration, neovascularization and revascularization, and activation of cardiac progenitor cells in the heart [16], [17]. Apart from the cardiac repair properties, it has been demonstrated that Tβ4 protects human corneal epithelial cells and conjunctival cells from apoptosis after ethanol and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) injury [18], [19], [20]. A few reports exhibit the role of Tβ4 in the myocardial infarction settings where it promotes endothelial and myocardial cell survival, cardiac cell migration, activation of integrin linked kinase (ILK) and activation of Akt/Protein Kinase B that resulted in improved cardiac function and reduction in scarring [14], [16], [21]. In this context, we have shown that Tβ4 also plays a crucial role in cardiac protection by enhancing the levels of PINCH-1-ILK-α-parvin components and promotes Akt activation while substantially suppressing NF-κB activation [22]. A recent report showed that Tβ4 upregulates anti-oxidative enzymes in human corneal cells against oxidative stress [23].

In this study, we used rat neonatal cardiac fibroblasts to study the effects of Tβ4 under oxidative stress. The rationale for using cardiac fibroblasts in this study originates from the fact that apart from being the most abundant cell type in the mammalian heart [24], [25], [26], the fibroblasts are intricately involved in myocardial development and cardiac protection under various stimuli [27], [28]. Recently, it has been shown that cardiac fibroblasts also undergo apoptosis under myocardial damage which can further aggravate the myocardial injury [29] and this can occur independent of the myocyte death [30]. The action of Tβ4 on cardiac fibroblasts under oxidative stress and its effects are largely unknown. It was for this reason we utilized the cardiac fibroblasts in the in vitro model to study the cardioprotective effects of Tβ4 under oxidative stress.

Here, we showed the effects of Tβ4 on ROS act ivy, antioxidant enzymes, anti-apoptotic and pro-fibrotic gene expression in preventing H2O2 induced oxidative stress in rat cardiac fibroblasts.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 5-Bromo-2-DeoxyUridine, (BrdU) all were purchased from Sigma Life Science (St. Louis, MO, USA). Thymosin β4 was purchased from ProSpec-Tany TechnoGene Ltd, (Rehovot, Israel). Dihydroethidium (DHE), 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFH-DA), diaminofluorescein 2-diacetate (DAF-2DA), 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6), and chloromethyl-X-rosamine (MitoTracker Red), ProLong Gold anti-fade mounting media (anti-fade) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). Primary antibody for Mn-SOD was purchased from Upstate/Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA); Cu/Zn-SOD from Assay Designs Inc., (Ann Arbor, MI, USA); catalase from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); collagen type I and collagen type III from Rockland Immunochemicals, (Gilbertsville, PA, USA); connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA), Bax, Bcl2, caspase-3 and GAPDH were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Protease inhibitor cocktail tablets were purchased from Roche GmbH, (Mann-heim, Germany). Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), non-essential amino acid cocktail, Antibiotic and anti-mycotic solution, insulin, transferrin and selenium (ITS), and fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) were all purchased from GIBCO, Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Cell culture and treatment

Primary cultures of cardiac fibroblasts were prepared from ventricles of 1–3 day-old Wistar rats as described [31], [32] and were plated at a field density of 2.5×104 cells per cm2 on coverslips, 6- well plates, 60 mm culture dishes, or 100 mm dishes as required with DMEM containing 10% FBS. After 24 h, cells were serum deprived overnight before stimulation. The dose of 100 µM H2O2 did not show any toxic effect and damage to the cells and was therefore used throughout the study. Tβ4 was pretreated 2 h before the H2O2 challenge at a final concentration of 1 µg/mL which was based on the previous report [23]. The cardiac cell culture experiments were approved by Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) and IACUC, Texas A & M University, Temple, TX.

Standardization of H2O2 dose on cardiac fibroblasts

To determine the optimal sub-lethal working concentration of H2O2 that is sufficient to induce oxidative stress but does not cause considerable cell death, the cell viability of cardiac fibroblasts under oxidative stress using a dose course of H2O2 (1 to 250 µM) was evaluated by MTT assay as described [33]. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, SpectraMax 250). The effect of Tβ4 (1 µg/mL) was assessed on the H2O2 challenge and the cytotoxicity curve was constructed and expressed as percentage cell viability compared to control. To rule out the possible direct interaction between MTT with H2O2 or Tβ4, the treatment media was aspirated before the addition of MTT solution.

Quantification of intracellular ROS levels

Cardiac fibroblasts after respective treatments were incubated with 50 µM H2DCFH-DA at 37°C in the dark for 30 min as described [33]. To rule out the possible direct cleavage of non-fluorescent DCFH-DA to fluorescent DCF by the nonspecific intracellular esterases and extracellular esterases in the serum, the treatment media was completely removed before H2DCFH-DA staining. Cells were then harvested, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and re-suspended in 50 mM HEPES buffer (5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4; 5 mM KCl, 140 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM glucose) before their fluorescence intensities were acquired by fluorimetry (SpectraMaxPro, USA).

Confocal Microscopy

For qualitative estimation of the levels of intracellular ROS, cells were seeded on coverslips in 6-well plates, treated and subsequently incubated with 50 µM H2DCFH-DA at 37°C in the dark for 30 min as previously described [33]. Cells were then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, washed 3 times with PBS, and mounted using anti-fade on glass slides and observed under confocal laser scanning microscope (Fluoview FV1000) fitted with a 488 nm argon ion laser. Images were acquired using the F10-ASW 1.5 Fluoview software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Since, ROS induces generation of other ROS species and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, we estimated the levels of other free radicals like superoxide and nitric oxide using fluorescent probes. For this, DHE, DAF-2DA and MitoTracker Red were used for estimation of superoxide (O2 .-) radicals, nitric oxide (NO) and mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), respectively [33]. Image intensities from 15–20 fields of at least 3–4 confocal images of the same treatment group were quantified using ImageJ version 1.34 (NIH, Bethesda, USA) as described previously by Elia et. al.[34]

Western blot analysis

For western blot analysis, cardiac fibroblasts were treated with or without Tβ4 for 2 h before treatment with 100 µM of H2O2. Cells were washed with PBS and cytosolic protein extracts were prepared using 1X Cell Lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) as per manufacturer's protocol. Aliquots of protein lysates (40 µg/lane) were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gels and western blotting was performed as described previously [31]. The primary antibodies used in this study include Mn-SOD, Cu/Zn-SOD, catalase, Bcl2, Bax, Caspase-3, Col-I, Col-III, CTGF and GAPDH. The detection was performed using chemiluminescence assay (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). Membranes were exposed to x-ray film to observe the bands (Kodak, Rochester, NY). The quantification of each western blot was measured by densitometry as described previously [31]. The changes observed as a result of H2O2 stimulation were expressed as fold change while the changes observed as a result of Tβ4 treatment were depicted as percent increase or decrease unless otherwise noted.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (q-RT-PCR) analyses

Total RNAs from the cardiac fibroblasts were extracted using RNEasy kit (Qiagen, Stanford, Valencia, CA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. For real-time RT-PCR, 200 ng to 1 µg of total RNAs was reverse transcribed to cDNA using high capacity cDNA synthesis kit (Applied Bio systems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocols. Quantitative PCR was then carried out in a MX-3005 real-time PCR equipment (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, USA), using 2 µl (20 ng) of cDNA template, 1 nmol of primers, and 12.5 µl of iQ SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in a total volume of 25 µl reaction. The primers used for the quantitative PCR are shown in Table 1. The cDNA were amplified with initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed PCR by 40 cycles of: 95°C 30 s, 60°C 30 s, 72°C 40 s and finally 1 cycle of melting curve following cooling at 40°C for 10 s. To confirm amplification specificity the PCR products from each primer pair were subjected to a melting curve analysis. Analysis of relative gene expression was done by evaluating q-RT-PCR data by 2(-ΔΔCt) method as described by others [35], [36]. Each experiment was repeated at least three times and GAPDH or 18S was used as housekeeping gene for internal control. The changes observed as a result of H2O2 stimulation were expressed as fold change while the changes observed as a result of Tβ4 treatment were depicted as percent increase or decrease unless otherwise noted.

Table 1. List of quantitative real-time PCR used in the study.

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

| CTGF | ACTATGATGCGAGCCAACTGC | TGTCCGGATGCACTTTTTGC |

| Collagen 1 | TGGCCTTGGAGGAAACTTTG | CTTGGAAACCTTGTGGACCAG |

| Fibronectin | TGCAGTGACCAACATTGATCGC | AAAAGCTCCCGGATTCCATCC |

| Mn-SOD | TGGACAAACCTGAGCCCTAA | GACCCAAAGTCACGCTTGATA |

| Cu/Zn-SOD | TGGGAGAGCTTGTCAGGTG | CACCAGTAGCAGGTTGCAGA |

| Catalase | ATCAGGGATGCCATGTTGTT | GGGTCCTTCAGGTGAGTTTG |

| Bcl2 | GTACCTGAACCGGCATCTG | GGGGCCATATAGTTCCACAA |

| BAX | CGAGCTGATCAGAACCATCA | GGGGTCCCGAAGTAGGAA |

| GAPDH | CCAGGTGGTTCCTCTGACTTC | GTGGTCGTTGAGGGCAATG |

| 18S | TGTTCACCATGAGGCTGAGATC | TGGTTGCCTGGGAAAATCC |

RNA interference and siRNA transfection

Silencing of Cu/Zn-SOD, catalase and Bcl2 proteins was achieved by using small interfering RNA (si-RNA) transfections. Pre-designed double-stranded si-RNA against Cu/Zn-SOD (SASI_Rn01_00112871), catalase (SASI_Rn01_00053417) and Bcl2 (SASI_Rn01_00062026) were purchased from Sigma Life Science (Saint Louis, MO, USA). As a negative control, non-targeting control si-RNA (scrambled si-RNA), verified to have no significant effect on most essential mammalian genes, was obtained from Sigma. Rat neonatal fibroblasts were seeded into 6-well plates with 3 mL of complete DMEM. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with 2 mL of Opti-MEM (Life Technologies). Cells were then transfected with 200 pmol of the siRNAs for catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD, Bcl2 or negative control siRNA using N-TER™ nanoparticle siRNA transfection system (Sigma) as per the manufacturer's protocol. After 24 h of transfection, cells were treated and harvested to determine the transfection efficiency and effect of Tβ4 in presence and absence of H2O2 treatment. Quantification of caspase-3 gene expression by q-RT- PCR was done to study the extent of pro-apoptotic gene expression.

TUNEL staining

Quantification of TUNEL staining was done to study the extent of apoptotic cell death on transfected fibroblasts by in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Briefly, 2×105 fibroblasts were seed on the coverslips in the 6-well plates, followed by siRNA transfections and treatment. The TUNEL staining was done using deoxyneucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and FITC-labeled 2′-deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate (dUTP) as per manufacturer's instructions. The Analysis was done using 3–5 images from hi-power field (40X objective) and the TUNEL index (%) was calculated as the number of TUNEL-positive cells divided by the total number of DAPI-stained nuclei.

Statistical analyses

All experiments were performed at least three times for each determination. Data are expressed as means±Standard Error (SE) and were analyzed using student t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and secondary analysis for significance with Tukey–Kramer post tests using Prism 5.0 Graph Pad software (Graph Pad, San Diego, CA, USA). A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Pretreatment with Tβ4 improves cardiac fibroblasts survival

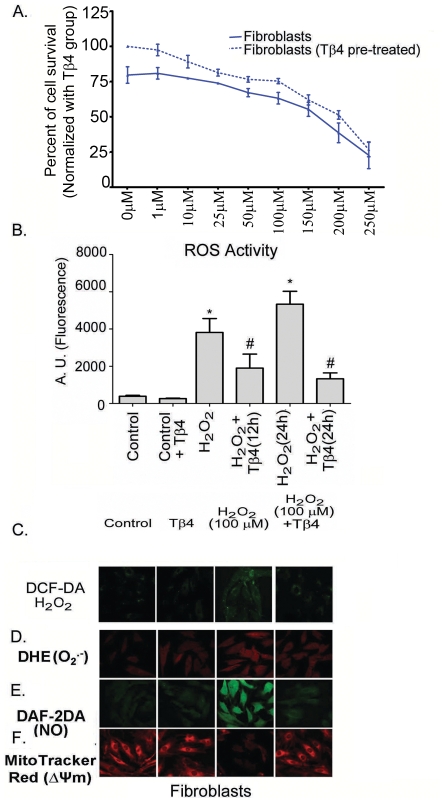

The viability of cardiac fibroblasts cells was assessed after treating the cells with various concentrations of H2O2 for 24 h by MTT assay. We observed that the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of H2O2 on these cells was between 150 and 250 µM (Figure 1A). Pretreatment with Tβ4 (1 µg/mL) resulted in an improved cell survival count (19.2%; p<0.05) compared to the untreated group. This beneficial effect of pretreatment was observed until 100 uM H2O2 concentration after which the pretreatment effect of Tβ4 was compromised. This indicated a potential role of Tβ4 in protecting the cardiac fibroblasts against cell death due to generation of ROS. The optimal concentration of H2O2 was determined from MTT experiment and thus standardized dose of 100 µM H2O2 which was used throughout the study.

Figure 1. Effect of Tβ4 on cell viability in H2O2 treated fibroblasts.

(A) The MTT assay was performed with increasing H2O2 concentration (1 to 250 µM) in presence (dotted lines) and absence (solid lines) of Tβ4 (1 µg/mL). Data represent means±SEM of 3 individual experiments. (B) Representative confocal laser scanning microscopy images of cardiac fibroblasts stained with DCF-DA showing the effect of Tβ4 on intracellular ROS upon treatment with H2O2. (C). Effect of Tβ4 on generation of ROS in fibroblasts treated with H2O2 by fluorimetry. The graph represents the percentage of fluorescence positive fibroblasts upon staining with DCF-DA. Data represent the mean±SE of at least three separate experiments. * means p<0.05 compared to the controls and # represents p<0.05 compared to the respective H2O2 treated group (D) Representative confocal laser scanning microscopy images of cells stained with DHE Red showing the effect of Tβ4 on generation of superoxide radicals upon treatment with H2O2 in fibroblast. (E). Representative confocal laser scanning microscopy images of cells stained with DAF-2DA showing the effect of Tβ4 on generation of nitric oxide upon treatment with H2O2 in fibroblast. (F). Representative confocal laser scanning microscopy images of cells stained with Mitotracker Red showing the effect of Tβ4 on loss of mitochondrial membrane potential upon treatment with H2O2 in fibroblast.

Tβ4 protects cardiac fibroblasts against H2O2 induced oxidative stress

Oxidative stress leads to detrimental changes in the cell signaling process. To determine whether Tβ4 has any effect on ROS activity under oxidative stress, intracellular ROS levels in the cardiac fibroblast were estimated after H2O2 treatment by confocal microscopy and fluorimetry. Cardiac fibroblasts treated with H2O2 showed enhancement of fluorescence intensity of DCF-DA by 9.9-fold at 12 h (p<0.01) and 13.8-fold at 24 h (p<0.01), respectively, compared to the untreated controls (Figure 1B). Pretreatment with Tβ4 showed a 50.2% decrease at 12 h (p<0.05) and 75.1% at 24 h (p<0.05), respectively, compared to H2O2 treated cardiac fibroblasts. Tβ4 treatment reduced the DCF-DA fluorescence by 32.2% (p<0.01) in the unstimulated cardiac fibroblast indicating that Tβ4 treatment was effective in preventing oxidative stress in cardiac fibroblasts. The confocal microscopy images matched with the quantitative fluorimetry results (Figure 1C). Our data indicated that Tβ4 abrogated the ROS activity significantly in cardiac fibroblasts.

Tβ4 reduces the formation of superoxide radicals and nitric oxide

Oxidative stress generated superoxide and nitric oxide radicals. These can lead to production of more noxious free radicals, like peroxynitrite (ONOO-). To evaluate the effect of Tβ4 in superoxide and nitric oxide radical generation in cardiac fibroblasts, we estimated the levels of those free radical generations from H2O2 treatment by using confocal microscopy. The confocal microscopy data showed that H2O2 treated cells enhanced the fluorescence intensity of DHE and DAF-2DA, an indicator of increased O2 .- and NO radicals, compared to the controls (Figure 1D and E). The enhanced fluorescence intensity of DHE and DAF-2A was prevented by Tβ4 pretreatment, compared to the H2O2 treated cells (Figure 1 D and E). The quantifications of image intensities were tabulated in Table 2. Together, our data suggest that Tβ4 attenuated H2O2 induced superoxide and nitric oxide radical generation in cardiac fibroblasts.

Table 2. Image intensities (Arbitrary Units) showing the fluorescence intensities in cardiac fibroblasts upon staining with DCF-DA, DHE, DAF-2DA and MitoTracker Red.

| S. No. | Staining | Control | Tβ4 | H2O2 | H2O2 + Tβ4 |

| 1 | DCF-DA (H2O2) | 259± 48 | 96±19* | 614±26* | 183±41# |

| 2 | DHE (O2 - radicals) | 428±52 | 461±81 | 892±62* | 659±35# |

| 3 | DAF-2DA (NO) | 305±43 | 274±43 | 948±47* | 308±41# |

| 4 | MitoTracker Red (Δψm) | 644±58 | 657±73 | 253±45* | 618±38# |

Data acquired from at least 15 fields taken from 3–4 different confocal images of the same treatment group and were quantified by using ImageJ Software.

*denotes p<0.05 compared to controls while.

denotes p<0.05, compared to the H2O2-treated group.

Tβ4 treatment prevents the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm)

Oxidative stress impacts the mitochondrial function leading to disruption of electron transport and loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential. We evaluated the effect of Tβ4 on the mitochondrial membrane potential in the cardiac fibroblast under H2O2 induced oxidative stress using MitoTracker® Red by confocal microscopy. Our data showed that there was loss of Δψm as indicated by a decrease in the fluorescence intensity of MitoTracker® Red in H2O2-treated cells. This decrease in the fluorescence intensity was prevented by the pretreatment with Tβ4 (Figure 1 F) suggesting that Tβ4 protected mitochondrial function by preventing the loss of Δψm in the cardiac fibroblast. The quantifications of image intensities were tabulated in Table 2. Our data suggest that Tβ4 treatment significantly reduced mitochondrial potential in H2O2 treated cardiac fibroblasts.

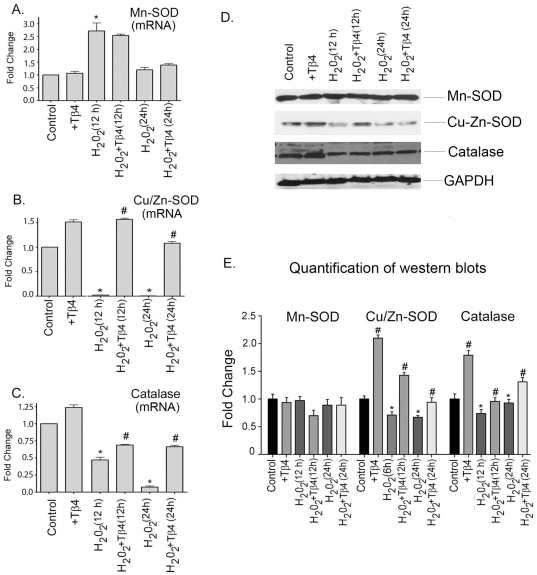

Tβ4 selectively upregulates the expression of antioxidant genes in cardiac fibroblasts under oxidative stress

We examined the effect of Tβ4 on mRNA expression of antioxidant genes like Mn-SOD, Cu/Zn-SOD and catalase in cardiac fibroblasts under oxidative stress by q-RT- PCR. Our data showed that there was an increase in the expression of Mn-SOD in the H2O2-treated cells by 2.7-fold and 1.3-fold increase at 12 and 24 h, respectively, compared to the untreated cells. Tβ4 treatment did not alter the mRNA expression of Mn-SOD at these time points, compared to the H2O2-treated groups (Figure 2A). H2O2 treatment reduced the mRNA expression of Cu/Zn-SOD by 95% at 12 h (p<0.05) and 98% at 24 h (p<0.05), respectively, compared to the untreated cells. Treatment with Tβ4 resulted in an increase of expression of Cu/Zn-SOD. Tβ4 pretreatment restored the Cu/Zn-SOD mRNA expression back to normal levels both at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to the H2O2 treated cells (Figure 2B). In unstimulated cell, the mRNA expression of catalase was upregulated by 1.3-fold after Tβ4 treatment. H2O2 treatment reduces the catalase mRNA expression by 50% (p<0.05) and 89% (p<0.05) at 12 and 24 h treatment, respectively, compared to the control. Pretreatment with Tβ4 upregulated the catalase mRNA expression by 1.5-fold (p<0.05), and 6.4-fold (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to the H2O2 treated cells (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Effect of Tβ4 on antioxidant genes under oxidative stress in cardiac fibroblasts.

Cells were treated with H2O2 in presence and absence of Tβ4 and (A) Mn-SOD, (B) Cu/Zn-SOD and (C) catalase, mRNA expression were analyzed at 12 h and 24 h, respectively by qRT-PCR. Data represent the means±SE of at least three separate experiments. (D) Western blot analysis showed the protein expression of Mn-SOD, Cu/Zn-SOD and catalase at 12 h and 24 h, respectively. GAPDH was used as internal loading control for the experiment. (E) Graph shows the relative fold change in the protein expression of Mn-SOD, Cu/Zn-SOD and catalase, respectively by densitometry. Data represent means±SEM from 3 individual experiments. * denotes p<0.05, compared to controls while # denotes p<0.05, compared to the H2O2-treated group.

To examine the status of the above antioxidant genes at the translational levels, western blots were performed. Our data showed that the expression level of Mn-SOD was relatively unchanged at protein level at 12 h and 24 h, respectively. Treatment with Tβ4 did not alter the expression of Mn-SOD (Figure 2D). Compared to the untreated cells, H2O2 treatment showed a decline of Cu/Zn-SOD protein expression by 23% (p<0.05) and 24.6% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to the controls. Cells pretreated with Tβ4 showed a 2.0-fold (p<0.05) and 1.4-fold (p<0.05) increased in the expression of Cu/Zn-SOD at 12 h and 24 h treatment, respectively, compared to the H2O2 treated cells (Figure 2D). The expression of catalase declined by 25% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 15% (p<0.05) at 24 h, respectively, with H2O2 treatment compared to untreated cells. Tβ4 pretreatment increased catalase expression by 1.3-fold (p<0.05) and 1.4-fold (p<0.05) increase at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to the H2O2 treated cells (Figure 2D). The normalized quantification for Mn-SOD, Cu/Zn-SOD and catalase expression by densitometry is shown in the Figure 2E.

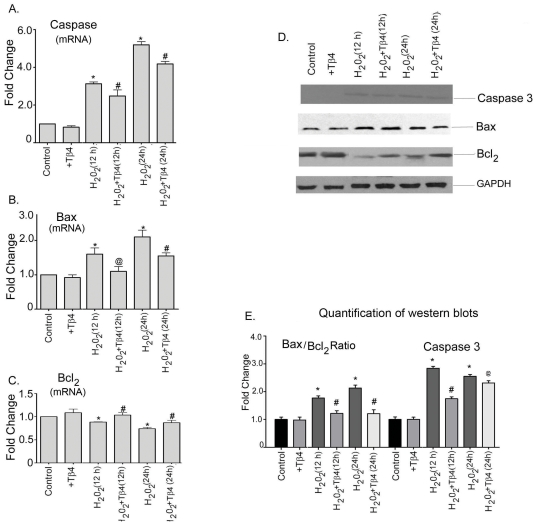

Tβ4 promotes cell survival by increasing the expression of anti-apoptotic genes and reducing the expression pro-apoptotic genes in cardiac fibroblasts under oxidative stress

To examine the effect of Tβ4 on cardiac death and survival, we determine the expression of caspase-3, Bax (pro-apoptotic) and Bcl2 (anti-apoptotic) in presence and absence of H2O2 by qRT-PCR. H2O2 treatment upregulated the caspase-3 expression by 3.0-fold (p<0.05) and 5.0-fold (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h treatment, respectively, compared to the untreated cells. Tβ4 pretreatment resulted in 29% (p<0.05) and 19% (p<0.05) decrease in the mRNA expression of caspase-3 at 12 h and 24 h treatment, compared to H2O2 treated cells (Figure 3A). H2O2 treatment increased mRNA expression of Bax by 1.6-fold (p<0.05) and 2.1-fold (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to untreated cells. The mRNA expression of Bax was reduced by 31% (p<0.05) and 26% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively with pretreatment Tβ4 treatment (Figure 3B). The mRNA expression of Bcl2 concomitantly decreased by 11% (p<0.05) and 23% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively in H2O2 treatment. The mRNA levels of Bcl2 was increased by pretreatment with Tβ4 by 20% (p<0.05) and 14% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to H2O2-treated cells (Figure 3 C).

Figure 3. Effect of Tβ4 on pro- and anti-apoptotic genes under oxidative stress in cardiac fibroblasts.

Cells were treated with H2O2 in the presence and absence of Tβ4 and (A) Caspase-3, (B) Bax and (C) Bcl2 mRNA expression were analyzed at 12 h and 24 h, respectively by qRT-PCR. Data represent the means±SEM of at least three separate experiments. (D) Protein expression of Caspase-3, Bax and Bcl2 at 12 h and 24 h, respectively. GAPDH was used as loading control for the experiment. (E) GAPDH was used as internal loading control for the experiment. (E) Graph shows the relative fold change in the protein expression of Bax, Bcl2 and caspase-3, respectively by densitometry. Data represent means±SEM from 3 individual experiments. * denotes p<0.05 compared to controls while # denotes p<0.05, compared to the H2O2-treated group and @ means p = ns compared, to the H2O2-treated group.

At translational level, H2O2 treatment resulted in a 2.8-fold (p<0.05) and 2.6-fold (p<0.05) increase in the expression of caspase-3 protein at 12 h and 24 h period, respectively, compared to the untreated cells. Tβ4 pretreatment showed 39% (p<0.05) and 9% (p = ns) decrease in the caspase-3 expression at the above time point, compared to H2O2-treated cells. (Figure 3 D). GAPDH was used as internal loading control. The normalized quantification of caspase-3 by western blotting is shown in the Figure 3E. H2O2 treatment showed an increase in the Bax/Bcl2 ratio by 1.8-fold (p<0.05) and 2.3-fold (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to the controls. Tβ4 treatment significantly prevented this increase in the Bax/Bcl2 ratio by 31% (p<0.05) and 43% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to H2O2-treated cells (Figure 3 E).

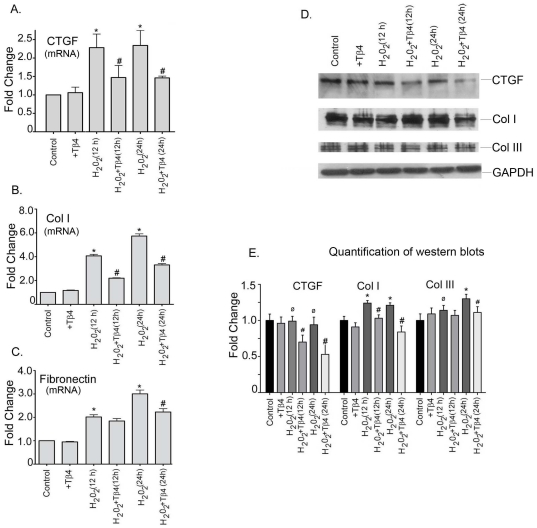

Tβ4 reduced the expression of pro-fibrotic genes in cardiac fibroblast under oxidative stress

We next determine the pro-fibrotic gene expression under oxidative stress condition. Our data showed that H2O2 treatment increased the mRNA expression of CTGF by 2.3-fold (p<0.05) and 2.3-fold (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to the controls. Tβ4 treatment showed reduction in the mRNA expression of CTGF by 17% (p<0.05) and 38% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively (Figure 4 A). The mRNA expression of collagen-1 was increased by 4.0-fold (p<0.05) and 5.7-fold (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, in H2O2-treated cells compared to the controls. Tβ4 pretreatment decreased collagen-I by 46% (p<0.05) and 42% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to the H2O2-treated cells (Figure 4 B). The mRNA expression of fibronectin was increased by 2.1-fold (p<0.05) and 3.3-fold (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, in the H2O2-treated cells. The mRNA expression of fibronectin in the Tβ4 treatment was decreased by 9% (p = ns) and 34% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to the H2O2-treated cells (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Effect of Tβ4 on profibrotic genes under oxidative stress in cardiac fibroblasts.

Cells were treated with H2O2 in the presence and absence of Tβ4 and (A) CTGF, (B) Col-I and (C) Fibronectin mRNA expression was analyzed at 12 h and 24 h, respectively by qRT-PCR. Data represent the means±SE of three separate experiments. (D) Western blot analysis showed the protein expression of CTGF, Col-I and Col-III at 12 h and 24 h, respectively. GAPDH was used as a loading control for the experiment. (E) Graph shows the relative fold change in the protein expression of Bax, Bcl2 and caspase-3, respectively by densitometry. Data represent means±SEM from 3 individual experiments. * denotes p<0.05, compared to controls while # denotes p<0.05 compared to the H2O2-treated group and ø denotes p>0.05, compared to controls.

At translational level, we did not observe any significant change in the CTGF protein level under oxidative stress. However, pretreatment with Tβ4 reduced the expression of CTGF by 27% (p<0.05) and 43% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to the H2O2 treated cells. The collagen-I protein expression also increased in H2O2 treatment by 24% (p<0.05) and 21% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h treatment, respectively, compared to the controls. Tβ4 treatment reduced collagen-I protein expression by 17% (p<0.05) and 30.5% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to the H2O2 treated cells. The collagen-III protein expression also increased in H2O2 treatment by 14% (p<0.05) and 30% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to controls. Tβ4 treatment reduced the collagen-III expression by 7% (p = ns) and 16% (p<0.05) at 12 h and 24 h, respectively, compared to the H2O2 treated cells (Figure 4 D). The normalized quantification of each western blot profile is shown (Figure 4 E).

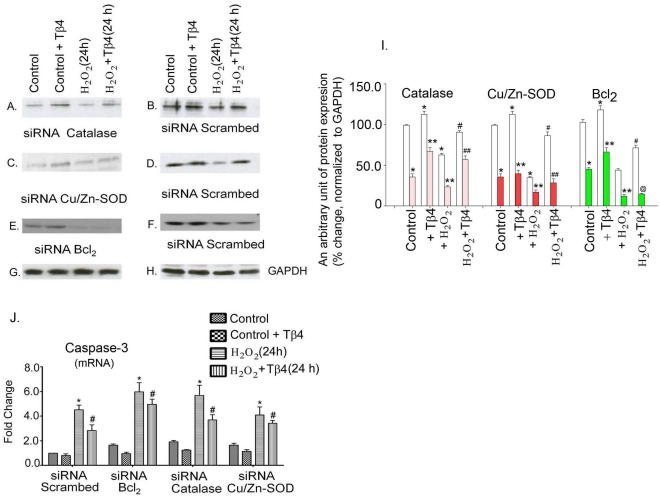

Effect of knocking down of Cu/Zn-SOD, catalase and Bcl2 in cardiac fibroblasts

We first determine the efficacy of siRNA mediated transfection of Cu/Zn-SOD, catalase and Bcl2 in cardiac fibroblasts. Western blots were performed to confirm the specific knock-down of Cu/Zn-SOD, catalase and Bcl2 in cardiac fibroblasts.

To determine whether Tβ4 has target for Cu/Zn-SOD, catalase and Bcl2, we tested the effect of Tβ4 in the cardiac fibroblasts either transfected with scrambled siRNA or siRNA of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD, and Bcl2 in the presence and absence of H2O2 induced oxidative stress. Treatment with scrambled siRNA did not alter the expression of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD, and Bcl2; therefore, scrambled siRNA treated group was taken as control for this experiment. Cardiac fibroblasts transfected only with scrambled siRNA showed 15.5±5.4%, 12.6±6.4% and 18.1±0.9% (p<0.05) increased protein expression of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD and Bcl2, due to Tβ4 treatment (Fig 5 B, D and E, 2nd lane). H2O2 treatment under non-silencing (scramble treated) conditions resulted in 38.4±4.2%, 63.3±3.1% and 56.4±4.6% (p<0.05) down regulation of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD, and Bcl2, respectively, compared to the control (Fig 5 B, D and E, 3rd lane vs. 1st Lane). In the scramble treated condition, Tβ4 pre-treatment resulted in significant upregulation of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD, and Bcl2 (44.6±3.2%, 145.6±11.2%, 62.1±5.7%; respectively, p<0.05), compared to H2O2 treated cardiac fibroblasts (Fig 5 B, D and E, 4th lane).

Figure 5. Effect of Tβ4 on antioxidant and antiapoptotic genes under siRNA knock down of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD and Bcl2 genes in cardiac fibroblasts under normal and oxidative stress condition.

Representative western blot illustrating the restoration of the expression of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD and Bcl2 in the cardiac fibroblasts upon knockdown of antioxidant and antiapoptotic genes, viz., (A) siRNA-catalase vs. (B) scrambled siRNA; (C) siRNA-Cu/Zn-SOD vs. (D) scrambled siRNA and (E) siRNA-Bcl2 vs. (F) scrambled siRNA, respectively. (G and H) GAPDH was used as an internal loading control for the above experiments. (I) Effect of Tβ4 on antioxidant and antiapoptotic genes under control and siRNA knock down of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD and Bcl2 genes in cardiac fibroblasts under normal and oxidative stress condition. Data represent the means±SE of at least three separate experiments. Clear bars represent the normalized protein expression of respective proteins in the si-scrambled RNA condition while the color bars represent the normalized protein expression under the respective siRNA knockdown conditions. * denotes p<0.05, compared to si-scramble control, # denotes p<0.05, compared to si-scramble and H2O2 treated group, ** denotes p<0.05, compared to si-RNA control group and ## denotes p<0.05, compared to the respective si-RNA and H2O2 treated group while @ denotes p = ns, compared to si-RNA and H2O2 treated group. (J) Bar graph shows relative fold-change in the mRNA expression of caspase-3 in Tβ4 pretreated cardiac fibroblasts under respective siRNA knockdown and H2O2 induced oxidative stress. Data represent the means±SE of at least three separate experiments. * denotes p<0.05, compared to controls while # denotes p<0.05 compared to the H2O2-treated group.

In comparison to the scrambled siRNA treated set (Fig 5B, D and F, 1st lane), our data showed 64.2±3.1% (p<0.05) knock-down of catalase, 77.1±2.9% (p<0.05) knock-down of Cu/Zn-SOD and 61.2±3.9% (p<0.05) knock-down of Bcl2, when their specific siRNAs were transfected into the fibroblasts (Figure 5A, C and E, 1st lane).

The down regulation in the levels of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD and Bcl2 proteins was abrogated by pre-treatment of Tβ4 (Fig 5 A, C and E, 2nd lane). We observed that the expression of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD, and Bcl2 was upregulated by 84.5±5.4%, 45.6±11.2%, 39.8±6.4%, respectively, p<0.05, compared to their control group (Fig 5 A, C and E, 1st lane). Furthermore, to evaluate the effect of Tβ4 under more stringent conditions, the siRNA-treated fibroblasts were subjected to H2O2 challenge, to further enhance the levels of oxidative stress. Our data showed that H2O2 treatment further depleted the levels of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD and Bcl2 (Figure 5A, C, E (3rd Lane). This dual stress ultimately reduced the expression of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD and Bcl2 to 23.3±3.8%, 17.2±4.1% and 12.7±2.1% (p<0.05) of the endogenous levels (Figure 5A, C, E; 3rd Lane). Tβ4 pretreatment resulted in a significant upregulation of catalase and Cu/Zn-SOD (142.4±7.3% and 36.5±4.1%, respectively, p <0.05) but not for Bcl2 (12.5±8.1%, p>0.05), compared to respective controls (Figure 5A, C, E (4th Lane). This implicates that under conditions Tβ4 restored the levels of catalase and Cu/Zn-SOD but failed to restore the expression of Bcl2. GAPDH was used as an internal loading control (Figure 5 G and H). The quantification of knock down of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD and Bcl2 protein and the restoration of their expression upon Tβ4 treatment is shown in Fig 5 I.

To test the effect of Tβ4 on induction of apoptosis, we further determined the expression of caspase-3, under the similar condition stated above. In scramble transfected cells, the expression of caspase-3 increased to 3.8-fold (p<0.05) in H2O2 treatment, which reduced by 26% (p<0.05) upon pretreatment with Tβ4 (Figure 5 J). In Bcl2 knocked down cells, the expression of caspase-3 increased by 1.7-fold (p<0.05), compared to the scrambled siRNA-transfected cells. H2O2 treatment potentiate a 6.0-fold (p<0.05) increase of caspase-3, suggesting an additive effect. Tβ4 treatment resulted in an 18% reduction (p<0.05) in the expression of caspase-3, compared to H2O2 stimulated cells (Figure 5J, second group). Similarly, knockdown of catalase gene resulted an increase of 2.1-fold (p<0.05) caspase-3 expression. H2O2 treatment showed an additive effect by increasing a 5.7-fold (p<0.05) of caspase-3. Tβ4 pretreatment resulted in a 25% (p<0.05) reduction in the caspase-3 activity in the H2O2 stimulated cells (Figure 5J, third group), compared to the H2O2-treated group. The expression of caspase-3 also increased by 1.5-fold (p<0.05) when Cu/Zn-SOD was knocked down in fibroblasts. H2O2 treatment under similar condition resulted in 4.1fold (p<0.05) increase of caspase-3 and Tβ4 pretreatment attenuated the caspase-3 activity by 18% (p<0.05), compared to H2O2 treated cells (Figure 5J, fourth group).

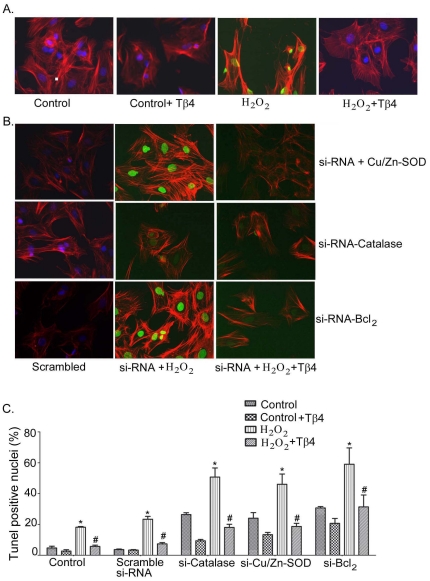

Finally, we performed TUNEL assay under the similar experimental conditions. Our data showed an increase of TUNEL positive nuclei in H2O2 treated cells as well as knockdown of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD, and Bcl2. Representative of fluorescence microscopy images of TUNEL positive nuclei (FITC-positive) are shown in Figure 6 A and B. Transfection with scrambled si-RNAs followed by H2O2 treatment showed an increase of TUNEL positive nuclei from 3.7±0.3 to 18.2±0.4. Furthermore, knockdown of catalase, Cu/Zn-SOD and Bcl2 resulted in a significant increase in the TUNEL positive nuclei to 26.3±1.2% (p<0.05), 24.0±3.6% (p<0.05) and 30.7±0.9% (p<0.05), respectively (Figure 6 C), compared with the control cells. H2O2 treatment in the similar experimental set up (knocked down cells), resulted an additive effect and increased the TUNEL positive nuclei to 50.7±5.9% (p<0.05) for catalase, 46.3±6.6% (p<0.05) for Cu/Zn-SOD, and 58.7±10.4% (p<0.05) for Bcl2, respectively, compared to the scramble si-RNA (23.2±1.9%). Pretreatment with Tβ4 in the H2O2 treated group resulted in a significant reduction in the TUNEL-positive nuclei to 18.0±2.1% (p<0.05) in si-RNA-catalase, 18.7±2.0% (p<0.05) in si-RNA Cu/Zn-SOD, and 31.3±7.8% (p<0.05) in si-RNA Bcl2, respectively (Figure 6 C). These results indicate that Tβ4 selectively targets antioxidant and anti-apoptotic genes to provide protection under oxidative stress.

Figure 6. Effect of Tβ4 on cardiac fibroblast apoptosis under oxidative stress.

(A) Representative fluorescent microscopy images of TUNEL staining in rat neonatal cardiac fibroblasts. Bright TUNEL-positive staining (FITC) was observed in H2O2 treatment which was not observed in control cells and cells pretreated with Tβ4. DAPI was used to stain the intact nuclei and counterstaining of filamentous actin was done with Texas Red®-X phalloidin. (B) Representative fluorescent microscopy images showing the effect of Tβ4 treatment in presence and absence H2O2-induced oxidative stress on cardiac fibroblasts transfected with siRNAs of Cu/Zn-SOD, catalase and Bcl2 vs. scrambled siRNA, respectively. (C) Bar graph shows the percent TUNEL-positive nuclei under similar experimental condition. Data represent the means±SE of at least three separate experiments. A total of 65 to 82 nuclei were counted for each observation. * denotes p<0.05 compared to controls while # denotes p<0.05, compared to the H2O2-treated group.

Discussion

The current study was aimed to determine the target molecules modulated by Tβ4 that enables it to prevent oxidative stress in an in vitro system using cardiac fibroblasts. H2O2 induced a marked increase in intracellular ROS in the cardiac fibroblasts. This increase in the intracellular ROS led to altered expression of antioxidant enzymes like the SODs and catalase. Increased ROS also led to the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and subsequently an increase in the Bax/Bcl2 ratio favoring apoptosis. This study shows for the first time that Tβ4 reduced the ROS accumulation by modulating the expression of antioxidant enzymes especially catalase and Cu/Zn-SOD and thereby preventing the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential. Additionally, Tβ4 upregulated the expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 and prevented apoptosis of cardiac fibroblasts in response to oxidative stress. Tβ4 failed to alleviate the oxidative stress and prevent cardiac apoptosis when these molecules were knocked down in the cells. Thus, Tβ4 possibly targets antioxidant and anti-apoptotic genes to provide protection under oxidative stress in cardiac fibroblasts.

The myocardium is composed of cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells and other cell types along with surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM). Apart from the myocytes, cardiac fibroblasts make up the bulk of the myocardium and important cell type as they can play crucial role in cardiac protection by providing sustenance, ECM support and defense against various stress conditions. Therefore, in this study, we used cardiac fibroblasts, so as to study the effect of Tβ4 on this cell type and to study how oxidative stress affects them in the in vitro system.

In the cardiac cells, H2O2 is known to induce oxidative stress and apoptosis. This system has been used on various occasions as a model to study the regulation of stress signaling stimuli in cell death [37], [38]. Here, we used this model system to show the effects of Tβ4 on H2O2 induced fibroblast cell death. Our results indicate that 2 h pretreatment with Tβ4 is able to significantly decrease the apoptotic effects of H2O2 in cardiac fibroblasts and thus protecting from cell death. These results suggest that intracellular and biochemical effects stimulated by Tβ4 treatment play a crucial role in the cardio-protection under oxidative stress. H2O2 treatment on cardiac fibroblasts leads to increase ROS accumulation especially O2 .-, H2O2 or OH-. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) converts O2 .- into H2O2 and the latter can generate hydroxyl (OH-) radicals in the presence of Fe2+ cations. ROS are able to oxidize biological macromolecules such as DNA, protein and lipids [39], [40], [41]. Also, NO can also be oxidized into reactive nitric oxide species, which may show behavior similar to that of ROS. In particular, the combination of NO and O2 .- can yield a strong biological oxidant, peroxynitrite that is more detrimental to the cells [42]. Oxidative stress causes altered expression of antioxidant enzymes SOD and catalase which prevents effective scavenging of the ROS formed as a result of H2O2 treatment in the fibroblasts. Our results show that Tβ4 restored the levels of Cu/Zn-SOD and catalase close to normal physiological level even under oxidative stress and thus scavenging the extra H2O2-induced ROS from the cellular system. One of the traditional hallmarks of ROS initiated cell death is mitochondrial dysfunction and energy depletion [43]. This is manifested by opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), the collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) and a concomitant drop in ATP production [44]. These events lead to cascade of cell destruction and apoptosis. Increased production of ROS in the failing heart leads to mitochondrial permeability transition [45], which causes loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, swelling of mitochondrial matrix, release of apoptotic signaling molecules, such as cytochrome c, from the inter-membrane space, and irreversible injury to the mitochondria [46]. Increased ROS in our system led to a decrease in the Δψm as evident by the staining with MitoTracker Red. This loss of Δψm was prevented by pretreatment of Tβ4. At this point, it is beyond our scope to investigate how Tβ4 modulate mitochondrial membrane potential under oxidative stress and, therefore, warranted further investigation.

Tβ4 was extremely effective in reducing intracellular ROS in H2O2 treated cardiac fibroblasts (Figure 2 A-C). Tβ4 acts via upregulation of selected antioxidant genes like Cu/Zn-SOD and catalase. In fact, the intracellular ROS level was markedly reduced when the cells were pretreated with Tβ4 at least 2 h prior to H2O2 exposure, suggesting that it might activate the key molecules that play an important role in the enzymatic antioxidant defense system. Another particularly relevant protein that loses function upon oxidation is Mn-SOD; its loss of function would further compromise antioxidant capacity and lead to further oxidative stress [47]. Both Mn-SOD and Cu/Zn-SOD have been reported to play a crucial role in protecting the cardiac cells from oxidative damage by scavenging ROS [48]. In our experimental system, we found that Tβ4 upregulated the expression levels of Cu/Zn-SOD and not Mn-SOD in cardiac fibroblast thus affording cardiac protection which is in contrast to the previous report by Ho et al [23]. This could be probably due to the different cell type used in the study. Catalase, which was directly responsible for H2O2 clearance, was upregulated by Tβ4 both at protein and gene level in the presence of H2O2, indicating that Tβ4 preferentially targets catalase which enables effecting scavenging of the H2O2 from the system. The mechanism of Cu/Zn-SOD and catalase upregulation by Tβ4 is currently unknown but, a transcription factor mediator activity has been postulated [49]. Tβ4 has been reported to translocate into the nucleus by an active transport mechanism or possibly through its cluster of positively charged amino acid residues (KSKLKK) but the exact function is still obscure. Alternatively, it might be the similar event like nuclear localization of actin where it is postulated that it might involve in chromatin remodeling [50], mRNA processing and transport [51].

Improved fibroblast survival during oxidative stress is important because increased fibroblast survival belittles the cardiac injury and prevents overall damage to the heart. Oxidative stress is known to trigger apoptotic cell death by up regulating the expression of pro-apoptotic protein like Bax which then dimerises and translocate to the outer mitochondrial membrane and aggregates to form pores that permit cytochrome c from mitochondria to cytosol [52]. Oxidative stress also leads to activation of caspase-3 cleavage and initiation of intrinsic apoptotic pathway [52]. Therefore, reduction in the production and accumulation of intracellular ROS is important to protect the cells from apoptosis triggered by the intrinsic pathway. Our data further showed that Tβ4 treatment inhibits excessive Bax expression and caspase-3 activation and enhance Bcl2 expression in fibroblast suggesting its protective effects under oxidative stress. As Tβ4 reduces the intracellular ROS levels, it would be reasonable to explain that Tβ4 probably promote the Bcl2/Bax ratio to protect the cells from apoptosis. To best of our knowledge, this is the first report that elucidates the beneficial effect of Tβ4 in cardiac fibroblast by up regulating the Bcl2/Bax ratio in favor of cell survival. This finding is in contrast to the previous report by Sosne et al, where they did not observe any change in the Bax/ Bcl2 expression [18]. This could be probably due to the different cell type used in the study. Although, there is no definitive mechanism by which Tβ4 exerts this anti-apoptotic effects, but, an internalization of Tβ4 has been proposed as one of the possible mechanism in human corneal epithelial cell under oxidative stress [19]. Alternatively, Tβ4 may use its methionine residues to react with intracellular oxygen at the post-translational level to generate sulfoxide, reducing the ROS level and eventually protects the cells from apoptosis [53].

Increased oxidative stress leads to pro-fibrotic changes in the fibroblasts [54], [55]. We observed that there was an increase in the expression of pro-fibrotic genes like CTGF, Collagen-I, Collgen-III and fibronectin in cardiac fibroblasts treated with H2O2. Decreased expression of fibrotic genes in the fibroblasts is beneficial because it prevents cardiac fibrosis and stiffening by reducing the ECM deposition. Our study showed that the increase in the pro-fibrotic gene expression was prevented by pretreatment of fibroblasts with Tβ4. These results corroborated with our previous observation in myocardial infarction (MI) model [22]. We showed that Tβ4 abrogated cardiac fibrosis in post-MI period by attenuating collagen type I and type III gene expression. This is the first report that elucidates the down regulation of pro-fibrotic gene expression by Tβ4 under oxidative stress.

Interestingly, we found that Tβ4 prevented apoptotic cell death by specifically targeting these antioxidant and anti-apoptotic molecules and when these antioxidant and apoptotic molecules were knocked down by si-RNA treatment; Tβ4 was not able to contribute its cardio-protective effects. These findings led us to suggest that Tβ4 provide cardiac protection by reducing the intracellular ROS levels and enhancing the expression of antioxidant enzymes (Cu/Zn-SOD and catalase) and anti-apoptotic protein (Bcl2) under oxidative stress.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that Tβ4 protects the cardiac fibroblasts against apoptosis by reducing intracellular oxidative stress through enhancing the expression of selected anti-oxidative enzymes and anti-apoptotic proteins. Given the preference of cardio-protective effects of Tβ4, it is still not clear how Tβ4 exerts its beneficial effects, is still under investigation. Although, Tβ4 is internalized by cells but the cell surface receptors are still not known. Furthermore, high concentration and ubiquitous presence of Tβ4 in the organs/tissues, it is reasonable to advocate that Tβ4 functions as an important intracellular mediator when either release from the cells or exogenously added, acts as a moonlighting peptide for repairing the damages tissues or cells [56], [57]. Our results not only offered more mechanistic explanation about the protective mechanism of Tβ4 but also supported the need to further investigate the use of this peptide in protecting the myocardium against oxidative damage in variety of disease condition where ROS has been implicated to play a damaging role. Also, further investigations are needed to explore the anti-fibrotic properties of Tβ4 which could be used to alleviate detrimental conditions like cardiac fibrosis, hypertrophy and heart failure.

Clinical Implications

Many studies have shown that there is a depletion of anti-oxidant levels due to aging especially in the heart, which makes it more vulnerable to damage especially under ischemia and under high pro-oxidant condition. We believe that the identified molecules (Cu/Zn-SOD, catalase and Bcl2) are important players under oxidative stress to mitigate the damage. Our findings indicated that the beneficial role of Tβ4 and its effects on upregulation of anti-oxidant genes under oxidative stress in the cardiac fibroblasts might be of clinical relevance. This makes Tβ4 a better therapeutic target and could have wider implications once translated from bench to bedside.

Limitation of the Study

In this study, we validated the effect of Tβ4 by selectively knocking down the anti-oxidant and apoptotic genes targeted by Tβ4 in cardiac fibroblasts. However, the possibility of interaction between these genes and other molecular pathways cannot be ignored. Also other off target effects of our anti-oxidative strategies with Tβ4 in conditions like cardiac fibrosis, cardiomyopathies and heart failure needs to be further investigated.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work is partly funded by Texas A&M start-up funds and a Scientist Development Grant from The American Heart Association to S. Gupta. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. No additional external funding was received for this study.

References

- 1.Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. A "reductionist" view of cardiomyopathy. Cell. 2007;130:401–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matata BM, Elahi MM. New York: Nova Biomedical Books. vi; 2007. Oxidative stress: clinical and biomedical implications. p. 330. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadoshima J. Redox regulation of growth and death in cardiac myocytes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1621–1624. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kukin ML, Fuster V. Vol. 291. Armonk, , NY: Futura Pub. xx,; 2003. Oxidative stress and cardiac failure. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen J, Shah PM. Cardiac hypertrophy and cardiomyopathy. In: Cohen Jules, Shah PravinM., editors. Proceedings of a symposium held October 1972 in Rochester, New York. New York: American Heart Assn; 1974. 223 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhalla AK, Singal PK. Antioxidant changes in hypertrophied and failing guinea pig hearts. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1280–1285. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.4.H1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maron BJ, Salberg L. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Pub. xi; 2006. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy : for patients, their families, and interested physicians. p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poornima IG, Parikh P, Shannon RP. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: The Search for a Unifying Hypothesis. Circ Res. 2006;98:596–605. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000207406.94146.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Saari JT, Kang YJ. Weak antioxidant defenses make the heart a target for damage in copper-deficient rats. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1994;17:529–536. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ide T, Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Utsumi H, Kang D, et al. Mitochondrial electron transport complex I is a potential source of oxygen free radicals in the failing myocardium. Circ Res. 1999;85:357–363. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George J, Struthers AD. Role of urate, xanthine oxidase and the effects of allopurinol in vascular oxidative stress. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:265–272. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s4265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bubb MR. Thymosin beta 4 interactions. Vitamins and hormones. 2003;66:297–316. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(03)01008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malinda KM, Goldstein AL, Kleinman HK. Thymosin beta 4 stimulates directional migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. The FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1997;11:474–481. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.6.9194528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bock-Marquette I, Saxena A, White MD, Dimaio JM, Srivastava D. Thymosin beta4 activates integrin-linked kinase and promotes cardiac cell migration, survival and cardiac repair. Nature. 2004;432:466–472. doi: 10.1038/nature03000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smart N, Risebro CA, Clark JE, Ehler E, Miquerol L, et al. Thymosin beta4 facilitates epicardial neovascularization of the injured adult heart. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1194:97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiu F-Y, Song X-X, Zheng H, Zhao Y-B, Fu G-S. Thymosin [beta]4 Induces Endothelial Progenitor Cell Migration via PI3K/Akt/eNOS Signal Transduction Pathway. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2009;53:209–214 210. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318199f326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein AL, Garaci E. Boston, Mass: Blackwell Pub. on behalf of the New York Academy of Sciences. xi; 2010. Thymosins in health and disease: 2nd international symposium. p. 230. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sosne G, Siddiqi A, Kurpakus-Wheater M. Thymosin-{beta}4 Inhibits Corneal Epithelial Cell Apoptosis after Ethanol Exposure In Vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1095–1100. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho JH-C, Chuang C-H, Ho C-Y, Shih Y-RV, Lee OK-S, et al. Internalization Is Essential for the Antiapoptotic Effects of Exogenous Thymosin {beta}-4 on Human Corneal Epithelial Cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:27–33. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sosne G, Albeiruti A-R, Hollis B, Siddiqi A, Ellenberg D, et al. Thymosin [beta]4 inhibits benzalkonium chloride-mediated apoptosis in corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells in vitro. Experimental Eye Research. 2006;83:502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shrivastava S, Srivastava D, Olson EN, DiMaio JM, Bock-Marquette I. Thymosin beta4 and cardiac repair. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1194:87–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sopko N, Qin Y, Finan A, Dadabayev A, Chigurupati S, et al. Significance of Thymosin beta4 and Implication of PINCH-1-ILK-alpha-Parvin (PIP) Complex in Human Dilated Cardiomyopathy. PloS one. 2011;6:e20184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho JH, Tseng KC, Ma WH, Chen KH, Lee OK, et al. Thymosin beta-4 upregulates anti-oxidative enzymes and protects human cornea epithelial cells against oxidative damage. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:992–997. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.136747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ieda M, Tsuchihashi T, Ivey KN, Ross RS, Hong T-T, et al. Cardiac Fibroblasts Regulate Myocardial Proliferation through 21 Integrin Signaling. Developmental cell. 2009;16:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leask A. TGFβ, cardiac fibroblasts, and the fibrotic response. Cardiovascular research. 2007;74:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Squires CE, Escobar GP, Payne JF, Leonardi RA, Goshorn DK, et al. Altered fibroblast function following myocardial infarction. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2005;39:699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jelaska A, Strehlow D, Korn JH. Fibroblast heterogeneity in physiological conditions and fibrotic disease. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1999;21:385–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown RD, Ambler SK, Mitchell MD, Long CS. The cardiac fibroblast: therapeutic target in myocardial remodeling and failure. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:657–687. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeda N, Manabe I, Uchino Y, Eguchi K, Matsumoto S, et al. Cardiac fibroblasts are essential for the adaptive response of the murine heart to pressure overload. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:254–265. doi: 10.1172/JCI40295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawaguchi M, Takahashi M, Hata T, Kashima Y, Usui F, et al. Inflammasome Activation of Cardiac Fibroblasts Is Essential for Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Circulation. 2011;123(6):594–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.982777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta S, Purcell NH, Lin A, Sen S. Activation of nuclear factor-κB is necessary for myotrophin-induced cardiac hypertrophy. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;159:1019–1028. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schorb W, Booz G, Dostal D, Conrad K, Chang K, et al. Angiotensin II is mitogenic in neonatal rat cardiac fibroblasts. Circ Res. 1993;72:1245–1254. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.6.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar S, Kain V, Sitasawad SL. Cardiotoxicity of calmidazolium chloride is attributed to calcium aggravation, oxidative and nitrosative stress, and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elia L, Contu R, Quintavalle M, Varrone F, Chimenti C, et al. Reciprocal regulation of microRNA-1 and insulin-like growth factor-1 signal transduction cascade in cardiac and skeletal muscle in physiological and pathological conditions. Circulation. 2009;120:2377–2385. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.879429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2-[Delta][Delta]CT Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murata H, Ihara Y, Nakamura H, Yodoi J, Sumikawa K, et al. Glutaredoxin exerts an antiapoptotic effect by regulating the redox state of Akt. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50226–50233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310171200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han H, Long H, Wang H, Wang J, Zhang Y, et al. Progressive apoptotic cell death triggered by transient oxidative insult in H9c2 rat ventricular cells: a novel pattern of apoptosis and the mechanisms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H2169–2182. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00199.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frank H, Thiel D, MacLeod J. Mass spectrometric detection of cross-linked fatty acids formed during radical-induced lesion of lipid membranes. Biochem J. 1989;260:873–878. doi: 10.1042/bj2600873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dean RT, Fu S, Stocker R, Davies MJ. Biochemistry and pathology of radical-mediated protein oxidation. Biochem J 324 ( Pt. 1997;1):1–18. doi: 10.1042/bj3240001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Breen AP, Murphy JA. Reactions of oxyl radicals with DNA. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;18:1033–1077. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy MP, Packer MA, Scarlett JL, Martin SW. Peroxynitrite: a biologically significant oxidant. Gen Pharmacol. 1998;31:179–186. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(97)00418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crawford DR, Davies KJ. Adaptive response and oxidative stress. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102(Suppl 10):25–28. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereira CV, Moreira AC, Pereira SP, Machado NG, Carvalho FS, et al. Investigating drug-induced mitochondrial toxicity: a biosensor to increase drug safety? Curr Drug Saf. 2009;4:34–54. doi: 10.2174/157488609787354440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiss JN, Korge P, Honda HM, Ping P. Role of the mitochondrial permeability transition in myocardial disease. Circ Res. 2003;93:292–301. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000087542.26971.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baines CP, Kaiser RA, Purcell NH, Blair NS, Osinska H, et al. Loss of cyclophilin D reveals a critical role for mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. Nature. 2005;434:658–662. doi: 10.1038/nature03434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP, Thompson JA. Peroxynitrite-mediated inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase involves nitration and oxidation of critical tyrosine residues. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1613–1622. doi: 10.1021/bi971894b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rahman K. Studies on free radicals, antioxidants, and co-factors. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2:219–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huff T, Rosorius O, Otto AM, Muller CS, Ballweber E, et al. Nuclear localisation of the G-actin sequestering peptide thymosin beta4. Journal of cell science. 2004;117:5333–5341. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen X, Ranallo R, Choi E, Wu C. Involvement of actin-related proteins in ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Molecular cell. 2003;12:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Percipalle P, Zhao J, Pope B, Weeds A, Lindberg U, et al. Actin bound to the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein hrp36 is associated with Balbiani ring mRNA from the gene to polysomes. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;153:229–236. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hori M, Nishida K. Oxidative stress and left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:457–464. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Young JD, Lawrence AJ, MacLean AG, Leung BP, McInnes IB, et al. Thymosin beta 4 sulfoxide is an anti-inflammatory agent generated by monocytes in the presence of glucocorticoids. Nature medicine. 1999;5:1424–1427. doi: 10.1038/71002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iglesias-De La Cruz MC, Ruiz-Torres P, Alcami J, Diez-Marques L, Ortega-Velazquez R, et al. Hydrogen peroxide increases extracellular matrix mRNA through TGF-beta in human mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2001;59:87–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suh JH, Shigeno ET, Morrow JD, Cox B, Rorcha AE, et al. Oxidative stress in the aging rat heart is reversed by dietary supplementation with (R)-{alpha}-lipoic acid. FASEB J. 2001;15:700–706. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0176com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldstein AL, Hannappel E, Kleinman HK. Thymosin beta4: actin-sequestering protein moonlights to repair injured tissues. Trends in molecular medicine. 2005;11:421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crockford D, Turjman N, Allan C, Angel J. Thymosin beta4: structure, function, and biological properties supporting current and future clinical applications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1194:179–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]