Background

Almost 9% of Canadian men experience some prostatitis symptoms over the course of a year, in about 6%, the symptoms are a bother,1 with approximately a third experiencing a remission of symptoms over a year during follow-up.2 Men with clinically significant prostatitis symptoms account for about 3% of Canadian male outpatient visits3 and causes significant morbidity4 and cost.5 Less than 10% of the patients suffer from acute or chronic bacterial prostatitis, conditions which are well-defined by clinical and microbiologic parameters and usually amenable to antimicrobial therapy. Acute prostatitis is characterized by a severe urinary tract infection (UTI), irritative and obstructive voiding symptoms with generalized urosepsis. Acute prostatitis responds promptly to antimicrobial therapy, and is usually self-limiting. Chronic bacterial prostatitis is usually associated with mild to moderate pelvic pain symptoms and intermittent episodes of acute UTIs. Long-term antimicrobial therapy is curative in about 60% to 80% of patients.

Most men with “chronic prostatitis” have chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS), characterized by pelvic pain (i.e., perineal, suprapubic, testicular, penile) variable urinary symptoms and sexual dysfunction (primarily pain associated with ejaculation).6 The National Institutes of Health-Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) is a reliable means of capturing the symptoms and impact of CP/CPPS.7 The etiology of this syndrome is not fully known, the evaluation has been controversial and treatment is, unfortunately, frequently unsuccessful. Focused multimodal therapy appears to be more successful than empiric monotherapy.

The recommendations presented in these guidelines were developed from North American NIH consensus meetings,8 International Consultation on Urologic Disease (ICUD)/World Health Organization (WHO) consensus meeting,9 European Guideline Committee recommendations,10 a recent comprehensive literature search performed by one of the authors11 and expert Canadian panel discussion. Medline and EMBASE databases were used to identify relevant studies published in English from 1949 (for Medline) or 1974 (for EMBASE) until January 31, 2011. We used search terms and strategies for each database.11 The levels of evidence and grades of recommendations were based on the ICUD/WHO modified Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine Grading System. These recommendations are summarized at the end of this guideline document. Within the document, the level of evidence and recommendation grade are included where appropriate and denoted as 3:A which means Level 3 evidence and Grade A recommendation.

Definition

Prostatitis describes a combination of infectious diseases (acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis), CPPS or asymptomatic prostatitis. The NIH classification of prostatitis syndromes12 includes:

Category I: Acute bacterial prostatitis (ABP) which is associated with severe prostatitis symptoms, systemic infection and acute bacterial UTI.

Category II: Chronic bacterial prostatitis (CBP) which is caused by chronic bacterial infection of the prostate with or without prostatitis symptoms and usually with recurrent UTIs caused by the same bacterial strain.

Category III: Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome which is characterized by chronic pelvic pain symptoms and possibly voiding symptoms in the absence of UTI.

Category IV: Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis (AIP) which is characterized by prostate inflammation in the absence of genitourinary tract symptoms.

Evaluation

A mandatory history is required for all patients at time of evaluation (4:C). The following presenting symptoms should be elicited: pain location (severity, frequency, and duration), lower urinary tract symptoms (obstructive/voiding and irritative/storage), associated symptoms (fever, other pain syndromes) and impact on activities/quality life. A comprehensive systems review should document past medical and surgical (particularly urologic) history, history of trauma, medications and allergies.

1. Acute bacterial prostatitis (NIH category I)

a. Physical examination

Mandatory (4:C): The abdomen, external genitalia, perineum and prostate must be examined. Prostate massage during a digital rectal examination (DRE) is not recommended.

b. Urine analysis and culture

Mandatory (2:A)

c. Imaging

Optional (2:A): A transrectal prostatic ultrasonography (TRUS) or computed tomography scan is indicated in ABP patients refractory to initial therapy to rule out prostate abscess/pathology. Pelvic ultrasound (or bladder scan) is indicated in ABP patients with severe obstructive symptoms, poor bladder emptying or physical examination findings of possible urinary retention. Initial imaging of the prostate is not recommended (3:B).

d. Serum PSA

Not recommended (3:C): Elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) associated with ABP usually leads to confusion and worry.

2. Chronic bacterial prostatitis (NIH category II)

a. Physical examination

Mandatory (4:C): This must include examination of the abdomen, external genitalia, perineum, prostate and pelvic floor.

b. Microbiological localization cultures of the lower urinary tract (4-Glass Test or 2-Glass Pre- and Post-Massage Test [PPMT])

Recommended (3:A): The 4-glass test is the criterion standard for the diagnosis of CBP. The 2- glass pre- and post-massage test (PPMT) is a simple and reasonably accurate screen for bacteria. Microscopy is optional. Rationale and description can be found in reference.6

c. Semen cultures

Not recommended (3:D): Based on limited evidence, semen cultures have not been shown to be significantly helpful in identifying men with CBP, unless the same organism causing recurrent UTIs is cultured.

d. Transrectal prostatic ultrasonography

Not recommended (3:B): A TRUS cannot be relied upon for differential diagnosis of categories of prostatitis. A TRUS can be considered optional (4:D) if there is a specific indication.

e. Urodynamics

Optional (4:D): Uroflow may be helpful to confirm obstruction. Urodynamics cannot be relied upon for differential diagnosis of categories of prostatitis, but may help document obstruction and/or bladder problems.

3. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (NIH category IIIA, IIIB)

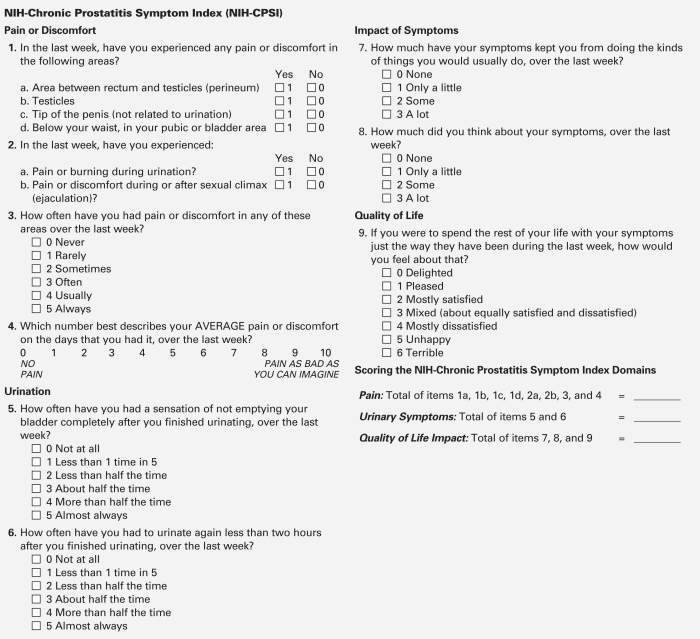

a. Symptom scoring questionnaire

Recommended (3:A)- the NIH-CPSI (Fig. 1) has become the established international standard for symptom evaluation (not for diagnosis) of prostatitis. The index has been shown to be reliable and can evaluate the severity of current symptoms and be used as an outcome measure to evaluate the longitudinal course of symptoms with time or treatment.

Fig. 1.

The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) captures the three most important domains of the prostatitis experience: pain (location, frequency and severity), voiding (irritative and obstructive symptoms) and quality of life (including impact). This index is useful in research studies and clinical practice. Adapted from Litwin et al.7 Reprinted with permission.

b. Physical examinations

Mandatory (4:C): Examination of abdomen, external genitalia, perineum and prostate is mandatory. Exacerbation of typical pelvic pain with normal DRE pressure is helpful in determining prostate centricity, while evaluating myofascial trigger points and/or possible musculoskeletal dysfunction of the pelvis and pelvic floor during DRE is believed to be helpful in treatment decisions.

c. 4-Glass test and 2-glass pre- and post-massage test (PPMT)

Recommended (3:A): Culture of the lower urinary tract urine specimens is recommended. The 4-glass test is the criterion standard to rule out CBP. The 2-glass PMT is a simple and reasonably accurate screen for bacteria. A rationale and description for this recommendation are available.6 At this time, there is no evidence that suggests that microscopy of the EPS or urine sediment adds any clinical value (microscopy optional).

d. Culture and/or microscopic examination of semen

Not recommended (3:D)

e. Cystoscopy

Not recommended (4:D) for routine evaluation. Optional (4:D): For selected patients. Endoscopy may be indicated in selected patients with obstructive voiding symptoms (refractory to medical therapy), patients with hematuria or other suspected lower urinary tract pathology.

f. Transrectal ultrasound

Not recommended (3:B) in routine practice, unless there is a specific indication.

g. CT scan and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Not recommended (3:B): At present, value is unknown.

h. Urodynamics

Optional (3:C): In selected men with obstructive voiding symptoms, it is reasonable to consider urodynamic evaluation (e.g., flow rates, post-void residual, pressure flow studies).

i. Serum PSA Levels

Not recommended (3:B): There is no evidence that serum PSA levels in patients with CP/CPPS will help diagnosis and direct therapy. Indications for serum PSA determinations should be the same as for men without CP/CPPS.

j. Psychological Assessment

Optional (3:B): There is accumulating evidence that psychosocial parameters, such as depression, maladaptive coping mechanisms (catastrophizing, resting as a coping mechanism) and poor social support impact symptoms and results of therapy. The physician should screen for these psychological problems.

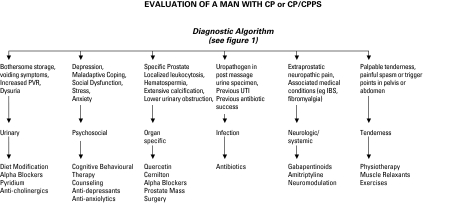

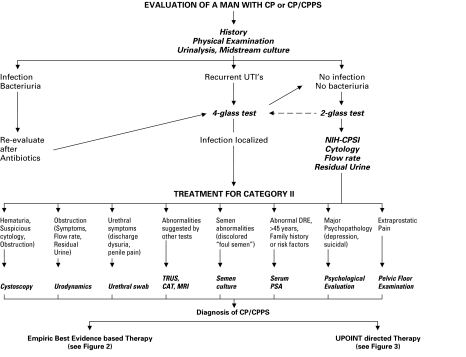

There is a practical algorithm to assess a man presenting with presumed CP/CPPS (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A best-evidence approach algorithm to manage chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome.

*amitriptyline, gabapentin, biofeedback, massage therapy, acupuncture, neurostimulation

4. Asymptomatic prostatitis (NIH category IV)

Investigations

Not recommended (3:C): While some evidence suggests that this category may have biological relevance, at this time there is no evidence that determination of asymptomatic prostatitis has any clinical relevance.

Treatment

1. Acute bacterial prostatitis (NIH category I)

ABP can be a serious infection with fever, intense local pain and general symptoms. Septicemia and urosepsis are always a potential risk. The following factors must be taken in account when treating ABP: potential urosepsis, choice of antimicrobial agent, urinary drainage, risk factors justifying hospitalization and auxiliary measures intended to improve treatment outcomes.13

a. Antimicrobial Therapy (2:A)

The choice and duration of antimicrobial therapy for ABP are based on experience and expert opinion and are supported by many uncontrolled clinical studies.14,15 For initial treatment of severely ill patients, the following regimens are recommended: intravenous administration of high doses of bactericidal antimicrobials, such as aminoglycosides in combination with ampicillin, a broad spectrum penicillin in combination with a beta-lactamase inhibitor, a third-generation cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone is required until defeverescence and normalization of associated urosepsis (this recommendation is based on treatment of complicated UTIs and urosepsis). Patients who are not severely ill or vomiting may be treated with an oral fluoroquinolone.14,15 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) is no longer recommended as first line empirical therapy in areas where TMP/SMX resistance for E. coli, the most frequent pathogen, is greater than 10% to 20%.15–19 Treatment should continue for 2 to 4 weeks.14,15

b. Urinary drainage (3:B)

A single catheterization with trial of voiding or short-term small caliber urethral catheterization is recommended for patients with severe obstructive voiding symptoms or urinary retention. Suprapubic tube placement is optional for patients who cannot tolerate a urethral catheter.

c. Hospitalization (3:B)

Hospitalization is mandatory in cases of hyperpyrexia, prolonged vomiting, severe dehydration, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension and other symptoms related to urosepsis. Hospitalization is recommended in high-risk patients (diabetes, immunosuppressed patient, old age or prostatic abscess) and those with severe voiding disorders.13

d. Drainage of prostate abscess (4:A)

Incision and drainage of prostate abscess are required in selected treatment refractory patients. Transurethral route appears to be modality of choice but abscess may be drained via perineum, rectum or transperineal route.

d. Auxiliary measures

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents have been suggested for reducing symptoms including fever.13–15 Alpha-blockers may be considered, particularly in men with moderately severe obstructive voiding symptoms to reduce the risk of urinary retention and facilitate micturition.13–15

2. Chronic bacterial prostatitis (NIH category II)

a. Antimicrobial therapy (2:A)

Because of their unique and favourable pharmacokinetic properties, their broad antibacterial spectra and comparative clinical trial evidence, the fluoroquinolones are the recommended agents of choice for the antimicrobial treatment of CBP.14,15,17,18 Data from CBP fluoroquinolone treatment trials with a follow-up of at least 6 months support the use of flouroquinolones as first-line therapy.20–28 The recommended 4- to 6-week duration of antimicrobial treatment is based on experience and expert opinion and is supported by many clinical studies.14,15,17,18 In general, therapeutic results (defined as bacterial eradication) are good in CBP due to E. coli and other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. CBP due to P. aeruginosa and Enterococci shows poorer response to antimicrobial therapy.18

CBP associated with a confirmed uropathogen that is resistant to the fluoroquinolones can be considered for treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (or other antimicrobials), but the treatment duration should be 8 to12 weeks.18

b. Alpha-Blockers (3:C)

The combination of antimicrobials and alpha-blockers has been suggested to reduce the high recurrence rate28 and this combination of two therapeutic regimens is considered optional for in-patients with obstructive voiding symptoms.

c. Treatment refractory cases

For treatment refractory patients with confirmed uropathogen localized to the prostate, the following are optional treatment strategies:

intermittent antimicrobial treatment of acute symptomatic episodes (cystitis) (3:A);

low-dose antimicrobial suppression (3:A); or

radical TURP or open prostatectomy if all other options have failed (4:C).

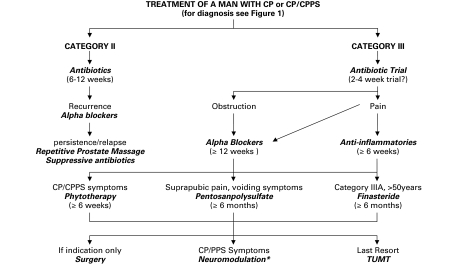

3. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (NIH category III)

The introduction of an internationally accepted classification system,12 a validated outcome index, the NIH-CPSI,7 and the significant number of randomized placebo controlled clinical trials published over the last decade and a half11 has permitted best-evidence based guideline recommendations. Twenty-three clinical trials29–54 were available at time of this guideline development. These English-language trials evaluated medical therapies using a prospective, randomized controlled design; these trials were used to support these recommendations. These have been recently reviewed and analyzed.11 We also used a literature search strategy.11 In addition, a best-evidence based treatment algorithm was used (Fig. 3).

a. Antimicrobials

Antimicrobials cannot be recommended for men with longstanding, previously treated CP/CPPS (1:A). However, uncontrolled clinical studies suggest that some clinical benefit can be obtained with antimicrobial therapy in antimicrobial naïve early onset prostatitis patients (4:D).

b. Alpha-blockers

Alpha-blockers cannot be recommended as a first line monotherapy (1:A). However, there is some evidence that alpha-blocker naïve men with moderately severe symptoms who have relatively recent onset of symptoms may experience benefit (1:A). Alpha-blocker therapy appears to provide benefit in a multimodal therapeutic algorithm for men with voiding symptoms (2:C)). Alpha-blockers must be continued for over 6 weeks (likely over 12 weeks).

c. Anti-inflammatory

Anti-inflammatory therapy is helpful for some patients, but is not recommended as a primary treatment (1:B); however, it may be useful in an adjunctive role in a multimodal therapeutic regimen (2:C).

d. Phytotherapies

Phytotherapies (specifically quercetin and the pollen extract, cernilton) are optional recommendations for first line (2:B) and combination multimodal therapy (3:C).

e. Other medical therapies

Other medical therapies, such as 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor therapy, pentosanpolysulfate and pregabalin, while not recommended as primary monotherapy (1:A), may provide benefit in selected patients (older men with LUTS for 5-ARI therapy, men with associated pain perceived bladder pain and irritative voiding symptoms for pentosanpolysulfate and neuropathic type pain for pregabalin).

f. Other potential medical therapies

Muscle relaxants, saw palmetto, corticosteroids, and tricyclic antidepressants have all been suggested6 and used, but recommendations will have to wait for results from properly designed randomized placebo controlled trials (4:D).

g. Physiotherapies

A number of physical therapies have been recommended,6 but they also suffer from a lack of prospective controlled data obtained from properly designed controlled studies. Prostatic massage, perineal or pelvic floor massage and myofascial trigger point release has also been suggested as a beneficial treatment modality for patients, however focused pelvic physiotherapy has yet to be shown to provide more benefit compared to SHAM physiotherapy. Biofeedback, acupuncture and electromagnetic therapy also show promise, but like all the other physical therapeutic modalities, require sham controlled trials before recommendations can be made (3:C).

h. Psychotherapies

Psychological support and therapy has been advocated based on new psycho-social modelling of this syndrome.55 This treatment ideally would include a cognitive behavioral therapy program. A referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist should be considered mandatory in patients with severe depression and/or suicidal tendencies.

i. Surgery

The evidence for surgical therapies has been reviewed.6 A number of minimally invasive therapies such as balloon dilation, neodymium:Yag laser, transurethral needle ablation, microwave hyperthermia and thermotherapy have been suggested (at this time, not recommended, 2:A). Further assessment of heat therapy employing sham controls, standardized inclusion exclusion criteria and validated symptom outcome measures are recommended. Pudendal nerve blocks or neurolysis surgery have been suggested for CPP that can be shown to be secondary to pudendal nerve entrapment (3:C). Other surgery, such as radical transurethral resection of the prostate and total prostatectomy, should not be encouraged and is not recommended (4:D) at this time for CP/CPPS since no definitive clinical series or long-term follow-up has ever been presented.

j. Multimodal Therapy (UPOINT)

A number of uncontrolled clinical studies have strongly suggested that multimodal therapy is more effective than monotherapy in patients with long-term symptoms.56,57 Individualized personal therapy algorithms directed toward clinically defined presenting phenotypes (UPOINT) have been proposed58 and the early results of such a strategy look promising.59 Based on the fact that monotherapies provide (at best) modest efficacy, a multimodal approach using specific clinical phenotypes to choose therapies is considered an optional recommendation.58 An algorithm has been proposed (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A clinical phenotype directed treatment (UPOINT) approach for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome.

4. Asymptomatic prostatitis (NIH category IV)

Therapy is not indicated (3:A) since these patients by definition are asymptomatic. However, antimicrobial therapy for selected patients with category IV prostatitis associated with elevated PSA, infertility and those planned for prostate biopsy may warrant consideration (3:C).

Fig. 2.

Diagnostic algorithm for a patient presenting with a chronic prostatitis syndrome.

Table 1.

Summary of recommendations (Level of Evidence: Grade of Recommendation)

EVALUATION

|

TREATMENT

|

Footnotes

Competing interests: J. Curtis Nickel reports being an investigator/consultant for Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Johnson and Johnson, Pfizer, Watson, Ferring, Taris and consultant for Farr Labs, Astellas, Triton, Trillium Therapeutics, Cernelle.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Nickel JC, Downey J, Hunter D, et al. Prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in a population based study employing the NIH-chronic prostatitis symptom index (NIH-CPSI) J Urol. 2001;165:842–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nickel JC, Downey JA, Nickel KR, et al. Prostatitis-like symptoms: one year later. BJU Int. 2002;90:678–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.03007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nickel JC, Teichman JM, Gregoire M, et al. Prevalence, diagnosis, characterization, and treatment of prostatitis, interstitial cystitis and epididymitis in outpatient urologic practice: The Canadian PIE Study. Urology. 2005;66:935–40. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNaughton-Collins M, Pontari MA, O’Leary MP, et al. Quality of life is impaired in men with chronic prostatitis: the chronic prostatitis collaborative research network. J General Inter Med. 2001;16:565–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calhoun EA, McNaughton-Collins M, Pontari MA, et al. The economic impact of chronic prostatitis. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1231–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nickel JC. Prostatitis and Related Conditions, Orchitis, and Epididymitis. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2011. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ, et al. The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. J Urology. 1999;162:369–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nickel JC. Clinical evaluation of the man with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2003;60(Suppl 6A):20–3. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaeffer AJ, Anderson RU, Krieger JN, et al. The assessment and management of male pelvic pain syndrome, including prostatitis. PART 2 Diagnostic workup and algorithms. In: McConnell J, Abrams P, Denis L, Khoury S, Roehrborn C, editors. Male Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction, Evaluation and Management; 6th International Consultation on New Developments in Prostate Cancer and Prostate Disease; June 24–27, 2005; Paris, France: Health Publications; 2006. pp. 3773–385. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fall M, Baranowski AP, Elneil S, et al. Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain Update 2008. Eur Assoc Uro Guidelines. http://www.uroweb.org/fileadmin/tx_eauguidelines/2008/Full/CPP.pdf. Accessed September 19, 2011.

- 11.Anothaisintawee T, Attia J, Nickel JC, et al. The Management of Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:78–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krieger JN, Nyberg LJ, Nickel JC. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA. 1999;282:236–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neal DE., Jr . Treatment of acute prostatitis. In: Nickel JC, editor. Textbook of Prostatitis. Oxford: ISIS Medical Media; 1999. pp. 279–84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjerklund Johansen TE, Gruneberg RN, Guibert J, et al. The role of antibiotics in the treatment of chronic prostatitis: a consensus statement. Eur Urol. 1998;34:457–66. doi: 10.1159/000019784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naber KG. Antimicrobial treatment of bacterial prostatitis. Eur Urol Suppl. 2003;2:23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warren JW, Abrutyn E, Hebel JR, et al. Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of uncomplicated acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women. Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:745–58. doi: 10.1086/520427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naber KG, Bergman B, Bishop MC, et al. EAU guidelines for the management of urinary and male genital tract infections. Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Working Group of the Health Care Office (HCO) of the European Association of Urology (EAU) Eur Urol. 2001;40:576–88. doi: 10.1159/000049840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naber KG. Antibiotic treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis. In: Nickel JC, editor. Textbook of Prostatitis. Oxford: ISIS Medical Media; 1999. pp. 285–92. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nickel JC. Management of urinary tract infections: historical perspective and current strategies: Part 2–Modern management. J Urol. 2005;173:27–32. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000141497.46841.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaeffer AJ, Darras FS. The efficacy of norfloxacin in the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis refractory to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and/or carbenicillin. J Urol. 1990;144:690–3. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39556-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrikkos G, Peppas T, Giamarellou H, et al. Four year experience with norfloxacin in the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis. 17th Int Congr Chemother; 1991. Abstr 1302. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pust RA, Ackenheil-Koppe HR, Gilbert P, et al. Clinical efficacy of ofloxacin(Tarivid) in patients with chronic bacterial prostatitis: preliminary results. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;1:469–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weidner W, Schiefer HG, Dalhoff A. Treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis with ciprofloxacin. Results of a one-year follow-up study. Am J Med. 1987;82:280–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weidner W, Schiefer HG, Brahler E. Refractory chronic bacterial prostatitis: a re-evaluation of ciprofloxacin treatment after a median follow-up of 30 months. J Urol. 1991;146:350–2. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37791-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naber KG, Busch W, Focht J. Ciprofloxacin in the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis: a prospective, non-comparative multicentre clinical trial with long-term follow-up. The German Prostatitis Study Group. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;14:143–9. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(99)00142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naber KG. Lomefloxacin versus ciprofloxacin in the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;20:18–27. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bundrick W, Heron SP, Ray P, et al. Levofloxacin versus ciprofloxacin in the treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis: a randomized double-blind multicenter study. Urology. 2003;62:537–41. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00565-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbalias GA, Nikiforidis G, Liatsikos EN. Alpha-blockers for the treatment of chronic prostatitis in combination with antibiotics. J Urol. 1998;159:883–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nickel JC, Krieger JN, McNaughton-Collins M, et al. Alfuzosin and symptoms of chronic prostatitis-chronic pelvic pain syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2663–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tugcu V, Tasci AI, Fazlioglu A, et al. A Placebo-Controlled Comparison of the Efficiency of Triple- and Monotherapy in Category III B Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CPPS) European Urology. 2007;51:1113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldmeier D, Madden P, McKenna M, et al. Treatment of category III A prostatitis with zafirlukast: A randomized controlled feasibility study. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:196–200. doi: 10.1258/0956462053420239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nickel JC, Pontari M, Moon T, et al. A randomized, placebo controlled, multicenter study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of rofecoxib in the treatment of chronic nonbacterial prostatitis. J Urol. 2003;169:1401–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000054983.45096.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elist J. Effects of pollen extract preparation Prostat/Poltit on lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with chronic nonbacterial prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Urology. 2006;67:60–3. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shoskes DA, Zeitlin SI, Shahed A, et al. Quercetin in men with category III chronic prostatitis: a preliminary prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Urology. 1999;54:960–3. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagenlehner FM, Schneider H, Ludwig M, et al. A pollen extract (Cernilton) in patients with inflammatory chronic prostatitis-chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a multicentre, randomised, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Eur Urol. 2009;56:544–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexander RB, Propert KJ, Schaeffer AJ, et al. Ciprofloxacin or tamsulosin in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized, double-blind trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:581–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-8-200410190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bates SM, Hill VA, Anderson JB, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind trial to evaluate the role of a short reducing course of oral corticosteroid therapy in the treatment of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. BJU Int. 2007;99:355–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nickel JC, Narayan P, McKay J, et al. Treatment of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome with tamsulosin: A randomized double blind trial. J Urol. 2004;171:1594–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000117811.40279.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaplan SA, Volpe MA, Te AE. A prospective, 1-year trial using saw palmetto versus finasteride in the treatment of category III prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2004;171:284–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000101487.83730.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheah PY, Liong ML, Yuen KH, et al. Terazosin therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: A randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Urol. 2003;169:592–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000042927.45683.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evliyaoglu Y, Burgut R. Lower urinary tract symptoms, pain and quality of life assessment in chronic non-bacterial prostatitis patients treated with (alpha)-blocking agent doxazosin; Versus placebo. Int Urol Nephro. 2002;34:351–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1024487604631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gul O, Eroglu M, Ozok U. Use of terazosin in patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome and evaluation by prostatitis symptom score index. Int Urol Nephro. 2001;32:433–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1017504830834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeong CW, Lim DJ, Son H, et al. Treatment for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: Levofloxacin, doxazosin and their combination. Urol Int. 2008;80:157–61. doi: 10.1159/000112606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leskinen M, Lukkarinen O, Marttila T. Effects of finasteride in patients with inflammatory chronic pelvic pain syndrome: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study. Urology. 1999;53:502–5. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mehik A, Alas P, Nickel JC, et al. Alfuzosin treatment for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study. Urology. 2003;62:425–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00466-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nickel JC, Downey J, Clark J, et al. Levofloxacin for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men: A randomized placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Urology. 2003;62:614–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00583-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nickel JC, Downey J, Pontari MA, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled multicentre study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of finasteride for male chronic pelvic pain syndrome (category IIIA chronic nonbacterial prostatitis) BJU Int. 2004;93:991–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nickel JC, Forrest JB, Tomera K, et al. Pentosan polysulfate sodium therapy for men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a multicenter, randomized, placebo controlled study. J Urol. 2005;173:1252–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000159198.83103.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye ZQ, Lan RZ, Yang WM, et al. Tamsulosin treatment of chronic non-bacterial prostatitis. J Int Med Res. 2008;36:244–52. doi: 10.1177/147323000803600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao WP, Zhang ZG, Li XD, et al. Celecoxib reduces symptoms in men with difficult chronic pelvic pain syndrome (Category IIIA) Braz J Med Biol Res. 2009;42:963–7. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2009005000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou Z, Hong L, Shen X, et al. Detection of nanobacteria infection in type III prostatitis. Urology. 2008;71:1091–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pontari MA, Krieger JN, Litwin MS, et al. Pregabalin for the Treatment of Men With Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1586–93. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nickel JC, O’Leary MP, Lepor H, et al. Silodosin for men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: Results of a Phase II multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Urol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.028. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nickel JC, Atkinson G, Krieger J, et al. Tanezumab therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS): Preliminary assessment of efficacy and safety in a randomized controlled trial AUA abstract 2011.

- 55.Nickel JC, Mullins C, Tripp DA. Development of an evidence-based cognitive behavioural treatment program for men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. World J Urol. 2008;26:167–72. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nickel JC, Downey J, Ardern D, et al. Failure of a monotherapy strategy for difficult chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2004;172:551–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000131592.98562.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shoskes D, Katz E. Multimodal therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Curr Urol Rep. 2005;6:296–9. doi: 10.1007/s11934-005-0027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nickel JC, Shoskes D. Phenotypic Approach to the management of the Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. BJU Int. 2010;106:1252–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Kattan M. Phenotypically Directed Multimodal Therapy for Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A Prospective Study Using UPOINT. Urology. 2010;75:1249–53. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]